Abstract

Objectives

Molecular markers associated with tumor progression in uterine carcinoma are poorly defined. In this study, we determine whether upregulation of LAMC1, a gene encoding extracellular matrix protein, laminin γ1, is associated with various uterine carcinoma subtypes and stages of tumor progression.

Methods

An analysis of the immunostaining patterns of laminin γ1 in normal endometrium, atypical hyperplasia, and a total of 150 uterine carcinomas, including low-grade and high-grade endometrioid carcinomas, uterine serous and clear cell carcinoma, was performed. Clinicopathological correlation was performed to determine biological significance. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data set was used to validate our results.

Results

As compared to normal proliferative and secretory endometrium, for which laminin γ1 immunore-activity was almost undetectable, increasing laminin C1 staining intensity was observed in epithelial cells from atypical hyperplasia to low-grade endometrioid to high-grade endometrioid carcinoma, respectively. Laminin γ1 expression was significantly associated with FIGO stage, myometrial invasion, cervical/adnexal involvement, angiolymphatic invasion and lymph node metastasis. Similarly, analysis of the endometrial carcinoma data set from TCGA revealed that LAMC1 transcript levels were higher in high-grade than those in low-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Silencing IAMC1 expression by siRNAs in a high-grade endometrioid carcinoma cell line did not affect its proliferative activity but significantly suppressed cell motility and invasion in vitro.

Conclusions

These data suggest that laminin γ1 may contribute to the development and progression of uterine carcinoma, likely through enhancing tumor cell motility and invasion. Laminin γ1 warrants further investigation regarding its role as a biomarker and therapeutic target in uterine carcinoma

Keywords: Uterine carcinoma, Endometrial carcinoma, Pathology, Laminin, Pathogenesis

1. Introduction

Uterine carcinoma is the most common gynecologic cancer in developed countries and is traditionally classified as two major types [1,2]. Approximately 80% of uterine carcinomas belong to the Type I category, comprising endometrioid carcinoma, and the remaining 20% belong to the Type II carcinomas, which are mainly composed of serous carcinoma. Patients with Type I neoplasms are younger and more predisposed to obesity and metabolic syndrome than those with Type II disease. Additionally, type I neoplasms often present at early and curable stages and assume a more indolent clinical course. In contrast. Type II uterine cancers are highly aggressive and are usually associated with cancer-related morbidity and mortality [3].

It has been well established that endometrioid (Type I) carcinoma develops from atypical hyperplasia and depends on estrogen stimulation to proliferate, while serous (Type II) carcinoma usually arises from atrophic endometrium or endometrial polyps and develops in an estrogen-independent fashion. Endometrioid and serous carcinomas have distinct molecular genetic alterations [4–10]. Endometrioid carcinoma is characterized by frequent somatic mutations in PTEN, ARID1A and CTNNB1, in addition to mutations in POLE and mismatch repair genes in a subset of tumors. In contrast, serous carcinomas harbor somatic TP53, PIK3CA, PPP2R1A and FBXW7 mutations but not those commonly detected in the endometrioid type. Serous carcinomas also exhibit gene amplification involving HER2 and CCNE1 [4,10]. Rarely, pure clear cell carcinomas of the endometrium are diagnosed, and these exhibit endometrioid-like and serous-like features, as well as “hybrid” characteristics in a subset of tumors [11].

We initially reported the emergence of the role of the laminin γ1 chain encoded by LAMC1 in gynecologic cancer when we applied RNA-Seq to compare the transcriptomes between ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma and normal fallopian tube epithelium the cell of origin of many ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas [15]. Among all LAM genes, LAMC1 showed the highest expression at the mRNA level and was the predominant laminin protein in high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. This gene was selected for further characterization because LAMC1 encodes an extracellular matrix protein, laminin γ1 chain, which is involved in several biological and pathological processes including tissue development, tumor cell invasion and metastasis [12–15]. Moreover, laminin proteins are present in the extracellular matrix and cell membrane, serving as potential biomarkers for detection. In this study, we extend the previous study by analyzing the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data and applying immunohistochemistry to determine the expression pattern of LAMC1 in different types of uterine carcinomas, as well as assessing the association of its expression levels with a variety of clinicopathological features.

2. Tissue samples and methods

2.1. Tissue materials

Anonymous formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue materials were retrieved from the archival files of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Shinshu University Hospital. They included 17 normal proliferative endometrium specimens, 17 normal secretory endometrium samples, 13 atypical hyperplasia (endometrial intraepithelial neoplasm) samples, and a total of 150 uterine carcinomas, including 76 grade 1 endometrioid, 21 grade 2 endometrioid and 23 grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas, as well as 27 uterine serous carcinomas and 3 pure clear cell carcinomas. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections from the study cases were reviewed by investigators (HK, YW and IS) to confirm the diagnosis, based on the criteria described in the 4th edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of Female Reproductive Organs [3]. One or two paraffin blocks from the qualified cases were retrieved and sequential unstained sections prepared to ensure tissue continuity in successive slides. The study was approved by the respective institutional review boards of both hospitals.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Laminin γ1 polyclonal antibody (cat # HPA001908, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used for immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical analysis of whole tissue sections was performed manually. Antigen retrieval was performed by placing sections in Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO) and incubating in a steamer for 30 min. The sections were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies, and immunoreactivity was developed by the Envision + System (Dako, Carpentaria, CA). The staining patterns in normal-appearing endometrial glands adjacent to a lesion were also recorded. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, and immunoreactivity was scored using the H-score system by two investigators based on the percentage of positively stained cells and the intensity of staining, which ranged from 0 to 3 +. A composite score was calculated by multiplying the intensity and extent scores (i.e., percentage of tumor cells being positive): 3 × percentage of strongly staining tumor cells (3 +) + 2 × percentage of moderately staining tumor cells (2 +) + percentage of weakly staining tumor cells (1 +), thus giving a range from 0 to 300.

2.3. Analysis of the TCGA data set

Level 3 TCGA data of uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma were retrieved from Broad Institute GDAC Firehose (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/) [4]. RNA-Seq version 2 data (gene-level normalized RSEM estimates) and clinical information were available for 396 uterine endometrioid carcinomas and 112 uterine serous carcinomas. RSEM, a software package for estimating gene and isoform expression levels, was used to analyze RNA-Seq data. Specifically, the mRNA expression levels were represented by “normalized RSEM count estimates” downloaded from the Broad Institute TCGA GDAC Firehose, and we performed log2 transformation for the downloaded data to obtain the measurements. RNS-seq version 2 data were processed through RSEM algorithm, which generated estimated counts as a proxy for RNA expression level. The RSEM count estimates were normalized to the 75th percentile for each sample (for each gene level estimates, the raw values were divided by the 75th percentile and then multiplied by 1000). Student's t-test was used to compare the log2 expression level of LAMC1 between endometrioid and serous carcinoma. One-way analysis of variance was employed to examine the association between log2 expression of LAMC1 and histological grade of endometrioid carcinomas, with Tukey's procedure used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Log-rank test was used to compare the survival between patients with high LAMC1 expression (> median) and low LAMC1 expression (≤ median) in endometrioid carcinoma. R version 3.1.3 was used for statistical analysis.

2.4. Cell culture, cell motility and invasion assay

The endometrioid cancer cell line, HEC1B, was originally obtained from the American Tissue Culture Center (Rockville, Maryland). HEC1B cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells per well, in DMEM/F-12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (500 IU/mL), and streptomycin (50 μg/mL) at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with two different LAMC1-specific short interfering RNA (siRNAs) (Ambion, cat #439240, ID # s8077 and s8078) and scramble siRNA (Ambion, cat # 4390849) as the control, with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Life technology, cat # 13778100). qRT-PCR and Western blot were used to determine the silencing efficiency at the mRNA and protein levels, respectively. For the Western blot experiment, cells were rinsed with PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40) with Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were separated using 4–15% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Western blotting was performed using the same anti-laminin γ1 antibody as was used in immunohistochemistry.

Cell motility and invasion assays were performed using the Transwell method, which quantified the migrated and invaded HEC1B cells. Uncoated inserts (354578; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were used for migration assays, while the inserts pre-coated with Matrigel (354480, BD Biosciences) were used for invasion assays. Cells were seeded in duplicate wells on the chambers above the inserts and cultured overnight Inserts were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, washed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The cells that had migrated to or invaded the underside of the membrane were visualized under a microscope. Cells were counted in five randomly chosen individual fields on each insert, and the data were expressed as the ratio of LAMC1 siRNA treated cells to the control siRNA treated groups.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of LAMC1 in uterine carcinoma subtypes

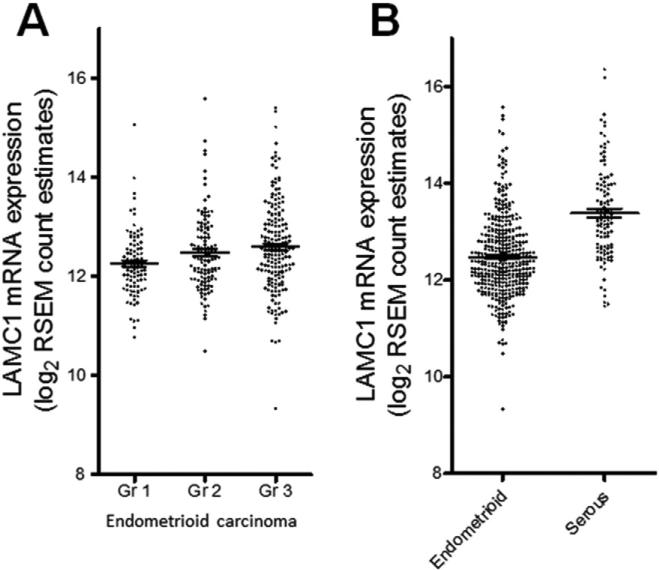

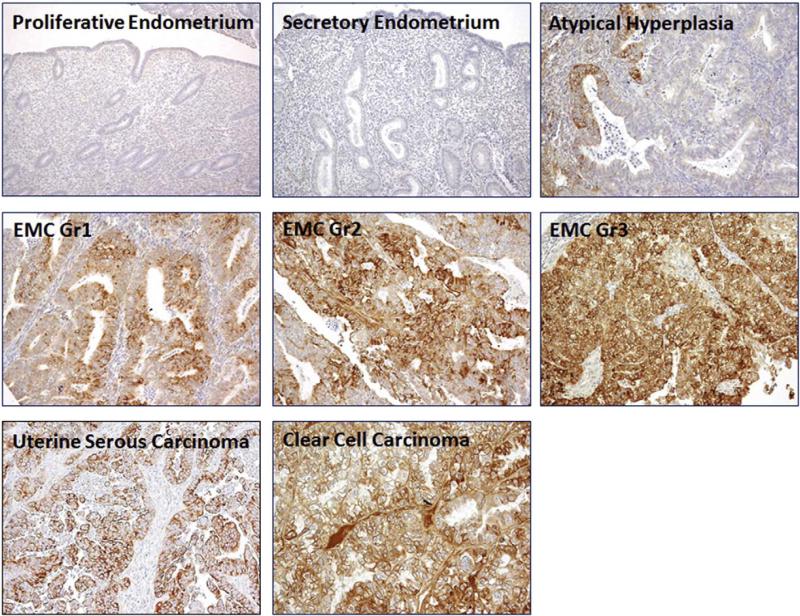

Analysis of the TCGA uterine carcinoma data set, which contained 396 endometrioid carcinomas and 112 serous carcinomas, demonstrated that higher mRNA levels of LAMC1 were associated with higher grades of endometrioid carcinoma (p = 0.0041, ANOVA) (Fig. 1A). In a pair-wise comparison, grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma showed a higher LAMC1 expression level than did grade 1 counterparts (t-test, p < 0.005), but there was no significant difference when grade 1 was compared to grade 2, or when grade 2 was compared to grade 3 carcinoma. Compared to endometrioid carcinoma (all grades combined), uterine serous carcinoma had a significant increase in LAMC1 mRNA levels (t-test, p < 22e – 16, two tailed) (Fig. 1B). LAMC1 expression was significantly higher in serous carcinoma than that in grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma (p = 3.07e – 11, t-test). To validate the above in-silica findings and further determine LAMC1 expression at the protein levels in different stages of tumor progression, including in normal endometrium and endometrial hyperplasia (which are not studied by the TCGA), we performed immunohistochemistry using an antibody specific to laminin γ1 chain in a total of 177 endometrial specimens. We observed undetectable or very focal and weak LAMC1 immunoreactivity in normal endometrium at both the proliferative or secretory phases (Fig. 2). When present, LAMC1 immunoreactivity was always found in the basement membrane outlining the basal parts of the glandular epithelium. Based on the H-score that was used to semi-quantify LAMC1 immunoreactivity, we observed an increase in the H-score in atypical hyperplasia as compared to normal endometrium (p < 0.01), but a more significant increase in H-score was detected in uterine carcinoma (p < 0.0001). In particular, high-grade (grade 2 and 3) endometrioid carcinoma expressed more LAMC1 protein than did low-grade (grade 1) tumor (p < 0.001). In addition, uterine serous carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma specimens were also analyzed and showed protein expression level similar to that of high-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Representative photomicrographs of LAMC1 stained sections are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig 1.

LAMC1 mRNA expression in the data set from TCGA uterine corpus carcinoma. A Comparison of LAMC1 mRNA expression in different grades of endometrioid carcinomas. Grade 3 (Gr 3) carcinomas have significantly higher expression levels than grade 1 (Gr 1). B. LAMC1 mRNA levels are higher in uterine serous carcinomas than those in endometrioid carcinomas (all grades combined).

Fig 2.

Laminin γ1 protein expression as assessed by immunohistochemistry and using the H-score system in normal endometrium and different grades and types of uterine carcinomas. The H-scores are higher in carcinoma tissues than normal proliferative endometrium [PEM), secretory endometrium (SEM) and atypical hyperplasia (AH) tissues. Endometrioid grade 3 carcinomas (EMG3) have higher H-scores than grade 1 tumors [EMG1). The results of statistical analyses of group comparison are listed.

Fig. 3.

Laminin γ1 immunoreactivity in representative samples of normal and neoplastic tissues. All images were captured at the same magnification. EMC: endometrioid carcinoma; Gn grade.

3.2. Correlation between LAMC1 expression and clinical features

Next, we determined the biological significance of LAMC1 expression in endometrioid carcinoma by correlating it with several clinicopathological features (Fig. 4). We demonstrated that LAMC1 H-scores were higher in more advanced clinical stages (DI and IV) than those in lower stages (I and II) (p < 0.0001). LAMC1 expression levels were also correlated with the presence of myometrial invasion (p = 0.016] and depth of invasion (more than half of myometrial thickness] (p = 0.023). Similarly, LAMC1 expression levels were higher in endometrioid carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion than in those without (p < 0.01). Moreover, higher LAMC1 H-scores were detected in endometrioid carcinoma specimens with lymphovascular invasion (p < 0.0001), with adnexal metastasis (p < 0.001), with lymph node metastasis (p < 0.0001) and in the presence of positive peritoneal cytology (p = 0.038). However, we did not observe any correlation between LAMC1 expression and overall survival in this cohort, as well as in the TCGA endometrioid carcinomas (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Result of laminin γ1 protein levels (as reflected by H-scores) in relation to clinicopathological parameters in endometrioid carcinoma. LVSI: lymph-vascular space invasion; LN meta: regional lymph node metastasis. +: present; –: absent.

3.3. The effects of silencing LAMC1 expression in endometrioid carcinoma cell line

Laminin plays an important role in promoting motility and invasion of tumor cells. This observation, together with our clinicopathologic findings described above, raised the possibility that increased LAMC1 expression contributes to tumor progression of uterine carcinomas by equipping tumor cells with greater ability to migrate and invade. Thus, we selected a high-grade endometrioid carcinoma cell line, HEC1B, and determined the effect of silencing LAMC1 expression on cell motility and invasion using in vitro assays. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, HEC1B cells expressed abundant LAMC1 mRNA and protein. The levels were significantly reduced in cells treated with two different siRNAs targeting LAMC1 as compared to mock transfected and control siRNA transfected cells. In this particular HEC1B cell line, cellular proliferation was not significantly affected by either LAMC1 siRNA at any time point (Fig. 5C). In contrast, both LAMC1 targeting siRNAs significantly reduced cell migration and invasion using in vitro systems (Fig. 5D and E).

Fig. 5.

The effects of LAMC1 knockdown by siRNAs on cellular proliferation, motility and invasion in HEC1B cells. A: LAMC1 mRNA is significantly decreased by either siRNAs targeting LAMC1. B: LAMC1 protein (laminin γ1) is significantly reduced after gene knockdown by both siRNAs as compared to mock transfection control and transfection with control siRNA. C Cellular proliferation is not affected by LAMC1 targeting siRNAs (blue and black lines) as compared to mock (red line) and control siRNA (green line) groups. D. Motility assay shows reduced LAMC1 expression by siRNAs reduces cellular motility. E. Both LAMC1 targeting siRNAs suppress cellular invasion as compared to control siRNA treated cells.

4. Discussion

Extracellular matrix proteins constitute an integral part of the tumor microenvironment and play critical roles in regulating tumor cell proliferation, survival, autophagy, migration, invasion, immune response, resistance to cytotoxic cnemotherapeutic drugs and epithelial–mesenchymal transition [16,17]. Laminins are heterotrimeric extracellular matrix glycoproteins that contain an α-chain, β-chain, and γ-chain, which are encoded by five α (α1-α5), four β (β1–β4), and three γ (γ1–γ3) different laminin (LAM) genes [12,15]. Their combination generates 16 known heterotrimeric laminin isoforms. Laminins represent a major component of the basal lamina, and the proteins network to form a structural scaffold that can bind to both cell membrane and extracellular matrix molecules [18]. It has been recently demonstrated that in addition to the degradation of the basement membrane, cervical cancer cells promote their invasion through the remodeling of the interstitial stroma, the process of which includes a decrease and partial replacement of collagens and fibronectin by a laminin-rich matrix [19].

We have previously demonstrated that LAMC1 was preferentially expressed in carcinoma from the ovary as compared to normal fallopian tube epithelium (FTE) [20]. Using immunohistochemistry, we demonstrated that the LAMC1 gene was preferentially upregulated not only in high-grade ovarian serous carcinomas but also in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), the precursor lesion of high-grade serous carcinoma, as compared to normal FTE Overexpression of laminin γ1 in essentially all STICs, including p53 negative cases, suggests that its immunostaining pattern can serve as a biomarker to diagnose STIC [20]. Thus, the results from the current study together with our previous report suggest that LAMC1 is a cancer-associated gene in both uterine and ovarian cancers.

Recently, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) consortium and other genome-wide studies have elucidated the molecular landscape of uterine corpus carcinoma and have demonstrated the heterogeneity of endometrial carcinomas of different molecular subtypes [4–10]. The results of these studies not only validate those molecular genetic changes previously reported in uterine endometrioid and serous carcinoma, but also provide new insight into its pathogenesis by demonstrating aberrations in several tumor-associated genes and pathways that may potentially participate in tumor initiation and progression. In this study, we queried the TCGA uterine corpus carcinoma database and were able to demonstrate that LAMC1 mRNA levels were significantly increased in grade 3 as compared to grade 1 endometrioid carcinomas.

The results from the current study have several biological and translational implications in studying uterine carcinomas. We observed an increased expression of LAMC1 in higher grades of endometrioid carcinoma as compared to normal endometrium and low-grade endometrioid carcinoma. This finding, together with a previous report demonstrating that other extracellular matrix proteins including aggrecan, vitronectin, tenascin R, nidogen and type VIII (chain α1) collagen and type XI (chain α) collagen are upregulated in endometrioid carcinoma [21], indicates a highly dynamic remodeling of the extracellular matrix during tumor progression. Our results from an in vitro cell motility and invasion assay suggest that expression of the laminin γ1 chain is required to promote cell motility and invasion of endometrioid carcinoma cells in culture. An interesting observation from this study is that in normal endometrial epithelial cells, LAMC1 immunoreactivity, when present, is exclusively located in the basement membrane. In contrast, LAMC1 immunoreactivity is detected on the entire cell surface in carcinoma cells, suggesting that this alteration of the LAMC1 expression pattern may be related to activation of LAMC1-mediated cell motility and invasion. This finding can explain why enhanced expression levels of LAMC1 are correlated with aggressive clinicopathological features in endometrioid carcinomas.

The molecular mechanisms behind upregulation of LAMC1 in uterine carcinoma are unclear. The LAMC1 gene does not appear to be amplified at the genomic scale, and it is therefore more likely that LAMC1 is regulated by epigenomic mechanisms. For example, miR-22 and miR-29a have been recently reported to target LAMC1, and transfection of miRNA mimics in prostate cancer cells induced apoptosis and diminished cell migration and viability [22,23]. It has been reported that Spl mediates transactivation of the LAMC1 promoter and coordinates its expression in human hepatocellular carcinomas [24], and future studies are required to delineate the specific pathways that are responsible for direct activation of the LAMC1 promoter.

Based on our analysis of the TCGA data set, we were able to demonstrate higher mRNA expression levels of LAMC1 in uterine serous carcinoma, a highly aggressive type II uterine cancer, than in endometrioid carcinoma, further supporting the contribution of LAMC1 expression to disease aggressiveness. However, immunohistochemical study did not show a significant difference between high-grade endometrioid and serous carcinoma. There are several explanations to this discrepancy. Immunohistochemistry can only semi-quantitatively measure protein expression at best and the method may not be sensitive to distinguish LAMC1 expression levels when it is overexpressed. Alternatively, mRNA levels may not reflect the protein levels in tumor tissues. Although distinguishing endometrial hyperplasia from carcinoma using the histopathological criteria is usually straightforward, the differential diagnosis can be problematic at times, especially in small curettage or biopsy specimens. Since the immunoreactivity of LAMC1 is almost always focal and weak (a lower H-score) in atypical hyperplasia, a more diffuse and intense staining would help support the diagnosis of endometrioid carcinoma in problematic cases. Since interaction of laminin with the laminin receptor is important to initiate signaling pathways that propel cell motility and invasion, an effort has been made to identify the inhibitors that are able to interrupt this interaction. Indeed, recent studies have discovered that new small molecules and RuBB-loaded EGCG-RuNPs nanoparticles are able to inhibit 67 kDa laminin receptor interaction with laminin and subsequently to suppress cancer cell invasion [25,26].

Although high LAMC1 expression levels are found to be significantly correlated with multiple poor prognostic factors in endometrial cancer patients, no correlation was found between LAMC1 expression and stage-adjusted overall survival in the cohorts from the TCGA and this study. It is possible that advanced endometrioid carcinomas with either high or low LAMC1 expression respond similarly to the standard chemotherapy after surgery and LAMC1 upregulation alone is insufficient to promote tumor recurrence. Thus, LAMC1 expression does not impact the overall survival from patients at the same clinical stages.

In summary, we provide new evidence that laminin γ1, encoded by the LAMC1 gene, is upregulated in many uterine carcinomas, especially in those showing clinically aggressive phenotypes. Future studies should aim at elucidating how the LAMC1 gene is upregulated during tumor progression and specifically how the molecular pathways that are altered during tumor evolution of uterine cancer affect LAMC1 expression [27]. It is also important to determine the translational roles of LAMC1 as a diagnostic marker and as a potential target for developing new target-based therapy.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Expression of LAMC1 encoding an extracellular matrix protein increased during tumor progression of endometrioid carcinoma.

LAMC1 expression was associated with stage, myometrial invasion, cervical/adnexal involvement, and lymph node metastasis.

Silencing LAMC1 expression significantly suppressed endometrioid carcinoma cell motility and invasion in vitro.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the OC100517 from US Department of Defense and Richard W. Telinde Research Program at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, Soslow RA, Zaino RJ, Kurman RJ. Endometrial Carcinoma. In: Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, editors. Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. 6th ed. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 393–452. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Cristofano A, Ellenson LH. Endometrial carcinoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2007;2:57–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaino R, Carinelli SG, Ellenson LH, Eng C, Katabuchi H, Konishi I, et al. Uterine corpus: epithelial tumors and precursor lesions. In: Kurman RJ, Carcangiu MX, Herrington S, Young R, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors – Gynecological Malignancy. IARC Press; Lyon: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Iiu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murali R, Soslow RA, Weigelt B. Classification of endometrial carcinoma: more than two types. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e268–e278. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang H, Cheung LW, Li J, Ju Z, Yu S, Stemke-Hale K, et al. Whole-exome sequencing combined with functional genomics reveals novel candidate driver cancer genes in endometrial cancer. Genome Res. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.137596.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao S, Choi M, Overton JD, Bellone S, Roque DM, Cocco E, et al. Landscape of somatic single-nucleotide and copy-number mutations in uterine serous carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:2916–2921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222577110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinde I, Bettegowda C, Wang Y, Wu J, Agrawal N, Shih Ie M, et al. Evaluation of DNA from the Papanicolaou test to detect ovarian and endometrial cancers. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:167ra4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Gallo M, O'Hara AJ, udd MLR, Urick ME, Hansen NF, O'Neil NJ, et al. Exome sequencing of serous endometrial tumors identifies recurrent somatic mutations in chromatin-remodeling and ubiquitin ligase complex genes. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn E, Wu RC, Guan B, Wu G, Zhang J, Wang Y, et al. Identification of molecular pathway aberrations in uterine serous carcinoma by genome-wide analyses. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1503–1513. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han G, Soslow RA, Wethington S, Levine DA, Bogomolniy F, Clement PB, et al. Endometrial carcinomas with clear cells: a study of a heterogeneous group of tumors including interobserver variability, mutation analysis, and immunohistochemistry with HNF-lbeta. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2015;34:323–333. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aumailley M. The laminin family. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2013;7:48–55. doi: 10.4161/cam.22826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engbring JA, Kleinman HK. The basement membrane matrix in malignancy. J. Pathol. 2003;200:465–470. doi: 10.1002/path.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gritsenko PG, Ilina O, Friedl P. Interstitial guidance of cancer invasion. J. Pathol. 2012;226:185–199. doi: 10.1002/path.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheele S, Nystrom A, Durbeej M, Talts JF, Ekblom M, Ekblom P. Laminin isoforms in development and disease. J. Mol. Med. 2007;85:825–836. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman-Baust CA, Weeraratna AT, Rangel LB, Pizer ES, Cho KR, chwartz DRS, et al. Remodeling of the extracellular matrix through overexpression of collagen VI contributes to cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neill T, L Schaefer RV. Iozzo, Instructive roles of extracellular matrix on autophagy. Am. J. Pathol. 2014;184:2146–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halper J, Kjaer M. Basic components of connective tissues and extracellular matrix: elastin, fibrillin, fibulins, fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin, tenascins and thrombospondins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;802:31–47. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7893-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fullar A, Dudas J, Olah L, Hollosi P, Papp Z, Sobel G, et al. Remodeling of extracellular matrix by normal and tumor-associated fibroblasts promotes cervical cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:256. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, oslow RAS, Han G, Sehdev AS, Morin PJ, et al. The diagnostic and biological implications of laminin expression in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012;36:1826–1834. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825ec07a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Futyma K, Miotla P, Rozynska K, Zdunek M, Semczuk A, Rechberger T, et al. Expression of genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins: a macroarray study. Oncol. Rep. 2014;32:2349–2353. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasqualini L, Bu H, Puhr M, Narisu N, Rainer J, Schlick B, et al. miR-22 and miR-29a are members of the androgen receptor cistrome modulating LAMC1 and Mcl-1 in prostate cancer. MoL Endocrinol. 2015;29:1037–1054. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishikawa R, Goto Y, Kojima S, Enokida H, Chiyomaru T, Kinoshita T, et al. Tumor-suppressive micraRNA-29s inhibit cancer cell migration and invasion via targeting LAMC1 in prostate cancer. InLJ. Oncol. 2014;45:401–410. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iietard J, Musso O, Theret N, L'Helgoualc'h A, Campion JP, Yamada Y, et al. Spl-mediated transactivation of LamCl promoter and coordinated expression of laminin-gammal and Spl in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:1663–1672. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pesapane A, Di Giovanni C, Rossi FW, Alfano D, Formisano L, Ragno P, et al. Discovery of new small molecules inhibiting 67 kDa laminin receptor interaction with laminin and cancer cell invasion. Oncotarget. 2015 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Yu Q, OJn X, Bhavsar D, Yang L, Chen Q, et al. Improving the anticancer efficacy of laminin receptor-specific therapeutic ruthenium nanopartides (RuBB-loaded EGCG–RuNPs) via ROS-dependent apoptosis in SMMC–7721 cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutter GL, Monte NM, Neuberg D, Ferenczy A, Eng C. Emergence, involution, and progression to carcinoma of mutant clones in normal endometrial tissues. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2796–2802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]