Abstract

African Americans have higher colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality rates. Research suggests that CRC screening interventions targeting African Americans be based upon cultural dimensions. Secondary analysis of data from African-Americans who were not up-to-date with CRC screening (n=817) was conducted to examine: 1) relationships among cultural factors (i.e., provider trust, cancer fatalism, health temporal orientation (HTO)), health literacy, and CRC knowledge; 2) age and gender differences; and 3) relationships among the variables and CRC screening intention. Provider trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy and CRC knowledge had significant relationships among study variables. The FOBT intention model explained 43% of the variance with age and gender being significant predictors. The colonoscopy intention model explained 41% of the variance with gender being a significant predictor. Results suggest that when developing CRC interventions for African Americans, addressing cultural factors remain important, but particular attention should be given to the age and gender of the patient.

Keywords: colorectal cancer screening, health care provider, trust, fatalism, health temporal orientation, health literacy, culture, colorectal cancer knowledge, African Americans

Although largely preventable, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the third leading cause of cancer death among African Americans.1-3 Using the results of previous research, several interventions have been developed that incorporate cultural factors in order to promote CRC screening.4-6 However, CRC incidence and mortality continue to affect African Americans at disproportionate rates.1,2 The most common cultural factors that have been examined in relation to cancer screening are health care provider (HCP) trust and cancer fatalism.7 In addition, health temporal orientation (HTO), a cultural factor which has been considered more recently, has been shown to influence CRC screening.6-9

Although it has been suggested that CRC screening interventions be targeted on cultural dimensions,4,6,7 few studies have examined how HCP trust, cancer fatalism, HTO, health literacy, and CRC knowledge influence CRC screening intention. In this paper, we will review these constructs and describe the results of a secondary analysis conducted to examine relationships among cultural factors (i.e., HCP trust, HTO, and cancer fatalism), CRC knowledge, health literacy, and CRC screening intention among urban African Americans who were not up-to-date with CRC screening. In addition, relationships among age, gender, and cultural variables will be examined. Additional knowledge about the relationships among these variables may inform the development of more effective CRC screening interventions for African Americans and decreased incidence and mortality from this often preventable disease. The following research questions guided the study:

-

1)

What are the relationships among HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, and CRC knowledge among African Americans?

-

2)

Are there age and gender differences in HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, and CRC knowledge among African Americans?

-

3)

Do HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, CRC knowledge, age, and gender predict CRC screening intention?

Conceptual framework

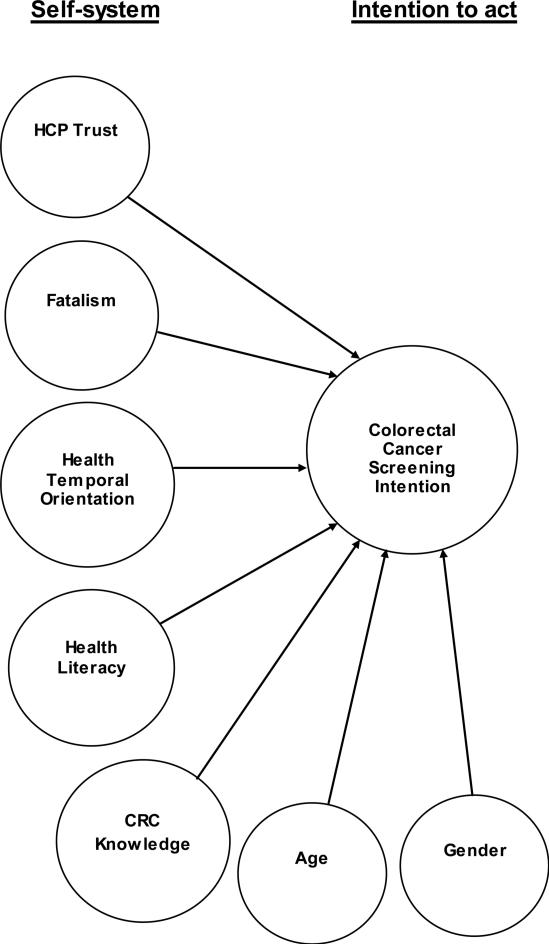

The Preventive Health Model (PHM)10 was the theoretical framework that guided this secondary data analysis. The PHM proposes that internal and external factors influence preventive health related actions (behaviors) which are reflective of a person's self-system.10 The PHM proposes that when faced with a health decision or problem (e.g. disease risk) the person forms an intention to act (e.g. to be screened or not screened) based on the relationships between the aspects of the self-system.11 For this secondary analysis, only a portion of the PHM was used: 1) self-system (i.e., HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, CRC knowledge, age, and gender) and 2) intention to complete a CRC screening test (i.e., FOBT or colonoscopy) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Framework: Cultural factors that influence colorectal cancer screening intention among African Americans

Background

Trust is a central feature of the patient-provider relationship.12,13 High levels of trust in one's health care provider (HCP) have been generally associated with greater use of recommended preventive services among African Americans.12-14 However, the relationship between HCP trust and CRC screening behaviors among African Americans has been mixed. For example, in one study, higher levels of HCP trust was the most significant predictor of CRC screening adherence (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.49-2.94).14 Yet another study found that HCP trust was not associated with FOBT completion.13 What has not often been considered is that gender may be important to consider when examining the relationship between HCP trust and CRC screening. Thus, the current study seeks to clarify as well as contribute to what is known about the relationships among HCP trust and the other study variables.

Cancer fatalism is the belief that one will certainly die as a result of being diagnosed with cancer (i.e., “that death is inevitable when cancer is present”).15 Cancer fatalism has been found to predict completion of CRC screening.5,16 Indeed, among older African Americans, fatalism was a significant predictor of FOBT completion after controlling for demographics such as age, education, and income. In addition, cancer fatalism has been found to mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and CRC screening behavior.16 Predictors of higher levels of cancer fatalism include older age, lower levels of education, lower income, lower levels of cancer knowledge, and lack of a provider recommendation for screening.15-18 The current study seeks to add to the body of literature about cancer fatalism by examining relationships among cancer fatalism, CRC screening intention, and other cultural variables. For example, prior CRC screening studies have not examined cancer fatalism in conjunction with other cultural factors such as HCP trust and health temporal orientation.3

Health temporal orientation (HTO) refers to the time perspective with which one makes health decisions (i.e., present time orientation vs. future time orientation).7,19 Future time orientation has been associated with a number of preventive health behaviors including intending to receive the HPV vaccine, use sunscreen, and undergo health screenings.8,20-22 In general, African Americans have been found to be more likely to be present-oriented compared to Whites.23 Among African Americans, present time orientation has been negatively associated with mammography as well as with CRC screening intention and adherence.3,8,9, 32, 33 Although the relationship between HTO and CRC screening has been examined in prior research,9,24 few studies have considered the influence of HTO on CRC screening intention while controlling for other constructs such as fatalism, CRC knowledge, and HCP trust among African Americans.

Knowledge of CRC screening consistently has been found to be associated with CRC screening intention and adherence.3,25-31 Previous studies have found that lack of knowledge about CRC screening was a significant barrier to completing CRC screening.13,30,31 For example, one study found that older African Americans lacked knowledge of CRC, CRC screening, and had difficulty listing CRC screening tests.31 The current study will add to what is known about cultural factors associated with CRC knowledge among African Americans.

According to Ratzan and Parker (2000), health literacy can be defined as “the degree which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions”32 It is widely known that health literacy impacts the use of preventive health services.33 Studies have found that low health literacy is associated with low CRC screening knowledge.34-36 However, another study found that perceived high-quality HCP communication mediated the association between low health literacy and low CRC screening knowledge.34 In order to improve CRC screening utilization, it is important to understand the relationships among health literacy, cultural factors such as HCP trust, CRC knowledge, and CRC screening adherence.

METHODS

Data were collected at baseline from 817 African Americans primary care patients who were enrolled in a randomized, controlled CRC screening intervention trial. The details of the parent study have been published elsewhere.37,38 Briefly, the intervention study aimed to compare the efficacy of two CRC screening interventions—a computer-delivered, tailored intervention and a non-tailored brochure.37,38 Participants were enrolled in Indianapolis, Indiana and Louisville, KY from 11 urban primary care clinics.37,38 Eligible participants self-identified as Black or African American, were 51 to 80 years old, and were currently non-adherent to CRC screening guidelines (i.e., had not had a fecal occult blood test [FOBT] in the past 12 months, a sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, or a colonoscopy in the past 10 years).37,38 Individuals were considered ineligible if they were adherent to CRC screening guidelines, had a personal history of CRC, a medical illness that precluded CRC screening, had a cognitive, speech, or hearing impairment, or did not speak English.37,38 Potential eligible individuals were identified through primary care clinic databases. 37,38 Following approval from their primary care provider, individuals were sent an introductory study brochure, informed consent documents, and a brochure explaining the study prior to an upcoming primary care clinic visit. 37,38 Those individuals who did not which to be contacted could call a toll-free number to opt-out of the study. 37,38 Within one week of the mailing, individuals were contacted by trained research staff who explained the study, assessed eligibility, and obtained consent. 37,38 Data for the current study were collected at baseline via a computer-assisted telephone interview system and in the case of the health literacy measure 6 months in person just prior to receipt of the intervention. 37,38 The current study analyzed data from 817 participants who completed study interviews at baseline and at 6 months.

Measures

HCP trust was measured using a 5-item scale developed by Dugan and colleagues.39 Participants responded to items using a Likert-type scale ranging from 4=strongly agree to 1=strongly disagree (α = 0.71). Higher scores on the HCP trust scale indicated greater levels of trust in one's HCP. Health temporal orientation was measured using a 9-item scale using responses ranging from 4=strongly agree to 1=strongly disagree. 40 The Cronbach's alpha obtained with this sample was 0.80). Higher scores on the HTO scale indicated a greater present time orientation. Cancer fatalism was measured using an 11-item scale modified from Powe's original scale.41 The Cronbach's alpha obtained with this sample was 0.86. Higher scores on the cancer fatalism scale indicated more fatalistic views of cancer. Health literacy was assessed using the brief version of the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine.42 CRC knowledge was assessed with an 11-item measure developed by the researchers (α = 0.63) with higher scores indicating greater knowledge of CRC, risk factors and screening. FOBT and colonoscopy intention were assessed by two separate dichotomous items that asked whether participants’ were planning to complete each of these tests in the next six months; response options were yes, no, and don't know. To make FOBT and colonoscopy intention dichotomous variables, 10 “don't know” responses were recoded as missing.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. To address the first two research questions, Pearson's correlations, t-tests, and chi-square analyses were run. In the case of continuous variables, t-tests were performed. In the case of categorical variables, chi-square tests were performed. To address the third research question, binary logistic regression models were run. All variables that were found to be statistically significant in the Pearson's correlation were included in the models. P-values of .05 or less were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Sample

Of the 817 participants included in this secondary data analysis, all participants identified themselves as African American or Black and 90% were not of Hispanic or Latino origin. The majority of the sample were women (53%) and the mean age of the participants was 57 years old (Table 1). The majority of the sample was not employed and had low income (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N = 817) | ||

| Male | 384 | 47 |

| Female | 433 | 53 |

| Health Insurance (N = 816) | ||

| Yes | 727 | 89 |

| No | 89 | 10.9 |

| Employed (N = 817) | ||

| Yes | 174 | 21.3 |

| No | 643 | 78.7 |

| Income (N = 785) | ||

| Less than $15,000 | 462 | 56.5 |

| $15,000-$30,000 | 231 | 28.3 |

| Greater than $30,000 | 92 | 11.2 |

| Age: Mean (SD) | 57.3 | 6.2 |

| Education: Mean (SD) | 12.19 | 1.9 |

Note: Columns may not total to 100% due to missing data

What are the relationships among HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, and CRC knowledge and age among African Americans?

Relationships among study variables were mixed (Table 2). HCP trust was positively associated with health temporal orientation (r = .31, p ≤ .01) but not significantly associated with health literacy, fatalism, or CRC knowledge. Health literacy was negatively associated with fatalism (r = −.23, p ≤ .01) and positively associated with CRC knowledge (r =.27, p ≤ .01). CRC knowledge was negatively associated with fatalism (r = −.30, p ≤ .01).

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Healthcare Provider Trust | - | |||||

| 2. Fatalism | .002 | - | ||||

| 3. Health Temporal Orientation | .31** | .03 | - | |||

| 4. Health literacy | −.02 | −.23** | −.04 | - | ||

| 5. CRC knowledge | −.01 | −.30** | .01 | .27** | - | |

| 6. Age | .02 | .08* | −.03 | .01 | −.07* | - |

Note:

correlation significant at p<0.01 level (2-tailed)

correlation significant at p<0.05 level (2-tailed).

Table 2 shows that age was positively associated with fatalism (r = .08, p ≤ .05) indicating that older participants had higher cancer fatalism scores. Age was negatively associated with CRC knowledge (r = −.07, p ≤ .05) indicating that older participants had less knowledge of CRC, risk factors and screening. Age was not significantly related to the remaining study variables.

Are there gender differences in HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, and CRC knowledge among African Americans?

Table 3 shows results of t-tests which indicated that men and women differed on health literacy scores (p ≤ .01) and CRC knowledge (p ≤ .05). There was a significant difference in the health literacy scores for men (M= 3.13; SD = 0.9) and women (M = 3.40; SD = 0.7) [t(462) = −4.48, p ≤ .01]. Among the study participants, there was a significant difference in the CRC knowledge scores for men (M= 3.37; SD = 2.06) and women (M = 3.83; SD = 2.40) [t(396) = −2.18, p ≤ .05]. The remaining study variables did not have significant differences between men and women.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of gender differences among study variables

| Gender | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Males | Females | t | df | p-value | Chi-square | df | p-value |

| HCP trust | 17.46 (3.02) | 17.02 (3.11) | 1.49 | 462 | .14 | |||

| Fatalism | 22.60 (7.99) | 22.07 (7.20) | 0.74 | 462 | .46 | |||

| HTO | 33.05 (3.41) | 32.88 (3.32) | 0.55 | 462 | .58 | |||

| Health literacy | 3.13 (0.9) | 3.40 (0.7) | −4.48 | 462 | .00 | |||

| CRC knowledge | 3.37 (2.06) | 3.83 (2.4) | −2.18 | 396 | .03 | |||

| FOBT intention | 50.40 | 1 | < .001 | |||||

| yes: | 206 (62%) | 126 (38%) | ||||||

| no: | 176 (37%) | 303 (63%) | ||||||

| Colonoscopy intention | 9.67 | 1 | < .002 | |||||

| yes: | 239 (52%) | 223 (48%) | ||||||

| no: | 143 (41%) | 208 (60%) | ||||||

Note. Standard deviations appear in parentheses below means. T-tests performed for continuous variables and chi-square tests performed for categorical variables.

Chi-square analyses were conducted to examine the differences in HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, CRC knowledge, FOBT intention, and colonoscopy intention by gender. However, a greater proportion of men (62%) indicated that they intend to have a FOBT in the next 6 months than women (38%), [χ2(1) = 50.4, p ≤ .01]. In addition, a greater proportion of participants who had 9th grade literacy levels or higher reported not intending to have a FOBT in the next 6 months (54%) compared to all other literacy levels (46%) [χ2(3) = 7.1, p ≤ .05]. The remaining variables (i.e., HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, and CRC knowledge) were not related to FOBT intention. The proportion of men (52%) intending to have a colonoscopy in the next 6 months was greater than that of the women (48%) [χ2(1) = 9.7, p ≤ .01]. The remaining variables (i.e., HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, and health literacy) were not related to colonoscopy intention.

Do HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, CRC knowledge, age, and gender predict screening intention?

Variables found to be significant at p≤.20 in the univariate analyses results were included in the FOBT intention and colonoscopy intention models.

Separate binary logistic regression models were run to examine whether HCP trust, fatalism, HTO, health literacy, CRC knowledge, age, and gender predicted FOBT intention and colonoscopy intention. The FOBT intention logistic regression model was statistically significant [χ2(7) = 14.77, p ≤.05], explaining 43% of the variation in FOBT intention. The only statistically significant predictors of FOBT intention were age (p = .02) and gender (p = .01). FOBT intention increased by .1 for each year of age and men were 1.7 times more likely than women to report they intended to have a FOBT in the next 6 months. The colonoscopy intention regression model was statistically significant [χ2(7) = 14.50, p ≤ .05] with 41% of the variance in colonoscopy intention explained. Gender (p = .01) was the only statistically significant predictor of colonoscopy intention with men 1.7 times more likely than women to report they intended to have a colonoscopy in the next 6 months.

DISCUSSION

The current study sought to examine the relationships among cultural variables (i.e., HCP trust, fatalism, and HTO), health literacy, and CRC knowledge and to explore potential age and gender differences in these variables. In addition, relationships among the aforementioned variables and intention to complete FOBT and colonoscopy were examined. Although many of these variables have been featured in prior studies of CRC screening, to the authors’ knowledge, no study has fully considered the relationships among the study variables and in relation to CRC intention among African Americans accessing primary care services who are currently non-adherent to CRC screening guidelines.

In the current study, HCP trust was not related to fatalism, CRC knowledge, FOBT intention, or colonoscopy intention. These findings support previous research that found that HCP trust does not impact a patient's fatalistic views of CRC screening or CRC knowledge.13 Unfortunately, few studies have examined HCP trust and intention to receive either FOBT and/or colonoscopy which makes it difficult to compare the results to previous research.

Supporting the findings of previous research, the results of the current study showed that cancer fatalism was negatively associated with health literacy and CRC knowledge .17-21 Previous research has found that people with fatalistic views about cancer were more likely to have lower health literacy scores and lower CRC knowledge.18, 43 However, in the current study, fatalism was not a significant predictor of FOBT or colonoscopy intention.

In the current study, having a future-time orientation was related to HCP trust but did not predict either FOBT intention or colonoscopy intention. Similar to previous research, HTO was significantly positively associated with HCP trust. That is, individuals who trust their health care providers are more likely to have a future time orientation. Indeed, in their discussion of trust in one's health care provider, Hall and colleagues referred to trust as a construct relating to future orientation, stating “...trust is primarily future–oriented (‘willingness to be vulnerable’)” (Hall, Camacho, Dugan, & Balkrishnan, 2002, p. 1422). The finding that HTO did not predict FOBT or colonoscopy intention is similar to past research where HTO did not predict FOBT or colonoscopy intention or adherence.3,9 However, on the other hand, the result of HTO not predicting CRC screening intention contradicts previous research on HTO in relation to many other preventive health behaviors.7, 25-30 This could be because prior studies examined HTO in the context of health behaviors common among younger people. However, previous studies included participants dissimilar to those in the current study; in prior research, participants were younger and the majority were not African American.20-22 It is important to consider that CRC screening may represent a unique health behavior. In addition, it may be important to examine potential differential relationships between HTO and various health behaviors based upon a number of demographic factors.

The current study results indicated that low health literacy was related to low CRC knowledge. This result supports previous studies found that African Americans with low health literacy also had low knowledge concerning CRC and CRC screening.35,36 Health literacy may be especially important to consider in the context of CRC screening because 1) many CRC screening interventions incorporate pamphlets or other materials that must be read and 2) written instructions accompany the screening test procedures themselves.

In the current study, age was positively related to fatalism and negatively related to CRC knowledge and FOBT intention; older study participants had higher fatalism scores and lower CRC knowledge and lower FOBT intention. These results are similar to previous research results that found that older African Americans were more likely to have fatalistic views about cancer which was related to lower CRC knowledge and lower cancer screening intention and adherence.17-21, 43,44 This finding may reflect older African Americans’ past experiences of witnessing the late diagnosis and poor prognosis of individuals in their community.

Results of the current study revealed that more men intended to receive either CRC screening test in the subsequent six months. This result is similar to past research were men have been shown to be more likely to have had CRC screening and be current with CRC screening when compared to women.45, 46

When the variables of this study were analyzed as part of the binary logistic regression analyses, the results indicated that the separate models predicting FOBT and colonoscopy were significant. An interesting finding is that only age and gender were significant predictors of FOBT intention in the FOBT model, and only gender was a significant predictor of colonoscopy intention in the colonoscopy model. These findings contradict the results of other CRC screening studies that have shown that cultural factors such as cancer fatalism predicted CRC screening.5,16 Although cultural variables did not predict CRC screening intention at baseline, future research will examine the relationship between cultural variables and actual CRC screening behavior at 18 months post-intervention.

This study has limitations that should be noted. First, the data used for this study were part of a larger study which tested two CRC screening interventions. Thus, it is possible that individuals who consented for the study are different from those who did not consent to the larger study. Second, this study of cultural factors and their relationship to CRC screening among African Americans was limited to men and women living in an urban area in the Midwest who had access to primary care. Region and having access to primary care have important influences on the variables of this study. In addition, the cultural factors utilized in the current study were measured only once: at baseline. However, it is possible that these factors may change over time, especially given that the interventions of the larger study aimed to increase CRC screening knowledge. Researchers designing future intervention studies which encourage CRC screening receipt should consider measuring these cultural variables at multiple time points.

Despite these limitations, these results can inform the development of CRC interventions targeting CRC behaviors among African Americans. Age and gender remain important factors in CRC screening intention. Interventions delivered to patients that are tailored based upon these demographic variables may be useful in promoting CRC screening. In addition, interventions that educate providers on methods of discussing CRC screening with women and individuals within age-eligible groups may also promote improved CRC screening intention among non-adherent individuals.

The results of the current study indicate that low levels health literacy continue to be associated with high levels of fatalism and low CRC knowledge. Improved health literacy may reduce the CRC health disparities experienced by African Americans. FOBT interventions should incorporate research-based strategies that improve health literacy, such as making sure the most important information about CRC screening is presented first, present only information about the FOBT, present the information about the test, preparation, and results in lay language and when possible use pictures and videos as supportive elements.47 Health care providers should also check for understanding when using written and verbal information about FOBT.47 An additional strategy for CRC screening may be to present the information about FOBT more than once to ensure comprehension and increase CRC screening intention.48 In addition, a nurse navigator may be useful in helping individuals with low health literacy to better understand the steps required for FOBT test completion.

The results of this study indicate that more research is needed to improve our understanding of the relationships between newer cultural variables, such as health temporal orientation, and well-established variables, such as cancer fatalism and CRC knowledge. Expanding what is known may help to strengthen targeted intervention strategies designed to increase CRC screening rates among African Americans.

Table 4.

Logistic regression to predict CRC screening intention

| FOBT intention |

Colonoscopy intention |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | Wald test | df | p | OR | 95% CI | Wald test | df | p |

| HCP trust | 1.0 | .92-1.06 | .10 | 1 | .75 | 1.02 | .96-1.09 | .39 | 1 | .53 |

| Fatalism | 1.02 | .99-1.05 | 2.06 | 1 | .15 | 1.00 | .98-1.03 | .17 | 1 | .67 |

| HTO | 1.0 | .93-1.05 | .21 | 1 | .65 | .98 | .92-1.04 | .60 | 1 | .44 |

| Health literacy | 1.14 | .87-1.50 | .92 | 1 | .34 | 1.25 | .97-1.62 | 2.92 | 1 | .09 |

| CRC knowledge | 1.01 | .92-1.11 | .06 | 1 | .80 | .97 | .89-1.05 | .57 | 1 | .45 |

| Age | 1.0 | .93-.99 | 5.37 | 1 | .02* | 1.01 | .98-1.05 | .85 | 1 | .36 |

| Gender | 1.70 | 1.12-2.51 | 6.25 | 1 | .01* | 1.73 | 1.16-2.57 | 7.37 | 1 | .01* |

Note. For FOBT intention, the overall model explained 43% of the variance (p=.04). For colonoscopy intention, the overall model explained 41% of the variance (p=.04).

Acknowledgements

The work of Ms. Christy was supported by the Training in Research for Behavioral Oncology and Cancer Control Program (R25CA117865; V. Champion, PI). The intervention trial was funded by a National Cancer Institute grant awarded to Susan M. Rawl, PhD, RN, FAAN (R01 CA115983; PI: Rawl). This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT00672828.

Funding for the intervention trial was funded by a National Cancer Institute grant awarded to Susan M. Rawl (R01 CA115983; PI: Rawl). Kelly Brittain is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan. Shannon M. Christy is a predoctoral fellow funded by the Training in Research for Behavioral Oncology and Cancer Control Program—R25 (R25 CA117865-06; PI: Champion) and a doctoral student in the Department of Psychology in the Purdue School of Science at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, Indiana. Susan M. Rawl is a Professor and Director of Research Training in Behavioral Nursing in the Indiana University School of Nursing in Indianapolis, Indiana. She is also a member of the Cancer Prevention and Control program at Indiana University Simon Cancer Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, Ga.: 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2014-2016. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, Ga.: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brittain K, Loveland-Cherry C, Northouse L, Caldwell CH, Taylor JY. Sociocultural Differences and Colorectal Cancer Screening Among African American Men and Women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39(1):100–107. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.100-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan PD, Fogel J, Tyler ID, Jones JR. Culturally targeted educational intervention to increase colorectal health awareness among African Americans. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:132–147. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip EJ, DuHamel K, Jandorf L. Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: A preliminary study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1685–1691. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9597-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powe BD, Ntekop E, Barron M. An intervention study to increase colorectal cancer knowledge and screening among community elders. Public Health Nursing. 2004;21(5):435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2004.21507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshpande AD, Sanders Thompson VL, Vaughn KP, Kreuter MW. The use of sociocultural constructs in cancer screening research among African Americans. Cancer Control. 2009;16(3):256–265. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitaker KL, Good A, Miles A, Robb K, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Socioeconomic inequalities in colorectal cancer screening uptake: Does time perspective play a role? . Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):702–709. doi: 10.1037/a0023941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brittain K, Murphy VP. Sociocultural and Health Correlates Related to Colorectal Cancer Screening Adherence Among Urban African Americans. Cancer Nursing. :9000. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000157. Publish Ahead of Print:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers RE. Decision Counseling in Cancer Prevention and Control. Health Psychology. 2005;24(4):S71–S77. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers RE, Daskalakis C, Cocroft J, Kunkel EJ, Delmoor E, Liberatore M. Preparing African-American Men in Community Primary Care Practices to Decide Whether or not to have Prostate Cancer Screening. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(8):1143–1154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling BS, Moskowitz MA, Wachs D, Pearson B, Schroy PC. Attitudes Toward Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:822–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling BS, Klein WM, Dang Q. Relationship of communication and information measures to colorectal cancer screening utilization: results from HINTS. J Health Commun. 2006;11(Suppl 1):181–190. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powe BD, Finnie R. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26(6):454–467. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles A, Rainbow S, von Wagner C. Cancer fatalism and poor self-rated health mediate the association between socioeconomic status and uptake of colorectal cancer screening in England. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, and Prevention. 2011;20(10):2132–2140. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dettenborn L, DuHamel K, Butts G, Thompson H, Jandorf L. Cancer fatalism and its demographic correlates among African American and Hispanic women: Effects on adherence to cancer screening. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2005;22(47-60) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powe BD, Daniels EC, Finnie R. Comparing perceptions of cancer fatalism among African American patients and their providers. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(8):318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2005.0049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukwago SN, Kreuter MW, Bucholtz DC, Holt CL, Clark EM. Development and validation of brief scales to measure collectivism, religiosity, racial pride, and time orientation in urban African American women. Family & community health. 2001;24(3):63–71. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orbell S, Kyriakaki M. Temporal framing and persuasion to adopt preventive health behavior: moderating effects of individual differences in consideration of future consequences on sunscreen use. Health Psychology. 2008;27(6):770–779. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Beek J, Antonides G, Handgraaf MJJ. Eat now, exercise later: The relation between consideration of immediate and future consequences and healthy behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54(6):785–791. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nan X. Relative persuasiveness of gain-versus loss-framed Human Papillomavirus vaccination messages for the present and future-minded. Human Communication Research. 2012;38:72–94. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown CM, Segal R. Ethnic differences in temporal orientation and its implications for hypertension management. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37(4):350–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker KL, Good A, Miles A, Robb K, Wardle J, von Wagner C. Socioeconomic inequalities in colorectal cancer screening uptake: Does time perspective play a role? Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):702–709. doi: 10.1037/a0023941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawl SM, Menon U, Champion V. Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Overview of Current Trends. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 2002;37:225–245. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(01)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bass S, Gordon T, Ruzek S, Wolak C, Ward S, Paranjape A. Perceptions of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Urban African American Clinic Patients: Differences by Gender and Screening Status. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26(1):121–128. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt CL, Roberts C, Scarinci I, et al. Development of a Spiritually Based Educational Program to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Among African American Men and Women. Health Communication. 2009;24:400–412. doi: 10.1080/10410230903023451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinney AY, Bloor LE, Martin C, Sandler RS. Social Ties and Colorectal Cancer Screening among Blacks and Whites in North Carolina. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2005;14:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brittain K, Taylor J, Loveland-Cherry C, Northouse L, Caldwell CH. Family Support and Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Urban African Americans. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2012;8(7):522–533. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(3):206–215. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shokar NK, Vernon SW, Weller SC. Cancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and screening preferences of a diverse patient population. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2000. Vol NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40(5):395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciampa PJ, Osborn CY, Peterson NB, Rothman RL. Patient numeracy, perceptions of provider communication, and colorectal cancer screening utilization. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 3):157–168. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller DP, Jr., Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, Pignone MP. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agho AO, Parker S, Rivers PA, Mushi-Brunt C, Verdun D, Kozak MA. Health literacy and colorectal cancer knowledge and awareness among African-American males. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education. 2012;50(1):10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christy SM, Perkins SM, Tong Y, et al. Promoting colorectal cancer screening discussion: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rawl SM, Skinner CS, Champion V, et al. Computer-delivered tailored intervention improves colon cancer screening knowledge and health beliefs of African Americans. Health Education Research. 2012;27(5):868–885. doi: 10.1093/her/cys094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell KM, Champion VL, Perkins SM. Development of cultural belief scales for mammography screening. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30(4):633–640. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.633-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayo RM, Ureda JR, Parker VG. Importance of Fatalism in Understanding Mammography Screening in Rural Elderly Women. Journal of Women & Aging. 2001;13(1):57–72. doi: 10.1300/J074v13n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, et al. Development and validation of a short- form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical Care. 2007;45(11):1026–1033. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith-Howell ER, Rawl SM, Champion VL, et al. Exploring the role of cancer fatalism as a barrier to colorectal cancer screening. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2011;33(1):140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powe BD, Hamilton J, Brooks P. Perceptions of Cancer Fatalism and Cancer Knowledge. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2006;24(4):1–13. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of Colorectral Cancer Screening Uptake among Men and Women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15(2):389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson N, Murff H, Ness R, Dittus R. Colorectal Cancer Screening among Men and Women in the United States. [July 3, 2014];Journal of Women's Health. 2007 16(1):57–65. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH, editors. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. Second ed. J. B. Lippincott Company; Philadelphia, PA 19106: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powe BD, Faulkenberry R, Harmond L. A Review of Intervention Studies that Seek to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Among African Americans. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2010;25(2):92–99. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.080826-LIT-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]