Abstract

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) interferes with host cell signaling by injecting virulence effector proteins into enterocytes via a type III secretion system (T3SS). NleB1 is a novel T3SS glycosyltransferase effector from EPEC that transfers a single N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) moiety in an N-glycosidic linkage to Arg117 of the Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD). GlcNAcylation of FADD prevents the assembly of the canonical death-inducing signaling complex and inhibits Fas ligand (FasL)-induced cell death. Apart from the DXD catalytic motif of NleB1, little is known about other functional sites in the enzyme. In the present study, members of a library of 22 random transposon-based, in-frame, linker insertion mutants of NleB1 were tested for their ability to block caspase-8 activation in response to FasL during EPEC infection. Immunoblot analysis of caspase-8 cleavage showed that 17 mutant derivatives of NleB1, including the catalytic DXD mutant, did not inhibit caspase-8 activation. Regions of interest around the insertion sites with multiple or single amino acid substitutions were examined further. Coimmunoprecipitation studies of 34 site-directed mutants showed that the NleB1 derivatives with the E253A, Y219A, and PILN(63–66)AAAA (in which the PILN motif from residues 63 to 66 was changed to AAAA) mutations bound to but did not GlcNAcylate FADD. A further mutant derivative, the PDG(236–238)AAA mutant, did not bind to or GlcNAcylate FADD. Infection of mice with the EPEC-like mouse pathogen Citrobacter rodentium expressing NleBE253A and NleBY219A showed that these strains were attenuated, indicating the importance of residues E253 and Y219 in NleB1 virulence in vivo. In summary, we identified new amino acid residues critical for NleB1 activity and confirmed that these are required for the virulence function of NleB1.

INTRODUCTION

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) is an extracellular diarrheagenic pathogen of children that utilizes a type III secretion system (T3SS) to inject virulence effector proteins directly into host intestinal cells. These effectors subvert host cell function and are encoded by genes either within the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (1) or outside the LEE (non-Lee-encoded [Nle] effectors) (2). A number of non-LEE-encoded effectors that disrupt host cell signaling have been characterized in recent years (3, 4). For example, both NleC and NleE inhibit NF-κB signaling and, consequently, block the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-8 (5–7). NleB1 was recently characterized to be a glycosyltransferase effector that modifies a conserved arginine residue in the Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) as well as the death domain-containing proteins TRADD and RIPK1, thereby blocking host death receptor signaling and apoptosis (8, 9). Modification of FADD prevents its recruitment to the Fas receptor and the subsequent recruitment and activation of caspase-8 (8, 9).

Glycosyltransferases are enzymes that catalyze the transfer of a sugar moiety from an activated sugar donor substrate containing a phosphate-leaving group, such as nucleoside diphosphate sugars, to a specific acceptor substrate (10, 11). Cytosolic glycosylation is a vital molecular mechanism by which various bacterial toxins and effector proteins subvert eukaryotic host cell function (12). For example, Clostridium difficile toxins A and B modify small Rho GTPases by mono-O-glucosylation at specific threonine residues (13). Glycosylated Rho GTPases are locked in an inactive state, inhibiting downstream signaling pathways, resulting in the disruption of the cell cytoskeleton, the induction of apoptotic cell death, and fluid accumulation in the large intestine (14).

The transfer of carbohydrate components to proteins usually occurs at the oxygen nucleophile of the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine side chain, resulting in the formation of an O-linked glycosidic linkage, or at the nitrogen nucleophile of the amide group of an asparagine side chain, forming an N-linked glycosidic linkage (15–19). O-GlcNAc modification, unlike classic O- or N-linked protein glycosylation, involves the transfer of a single GlcNAc moiety to the hydroxyl group of a serine or threonine residue, and this modification is not elongated (17, 20). A nonclassical N-linked modification involves the addition of single glycosyl moieties from activated nucleotide sugars to asparagine residues of the target protein (21–23). NleB1 catalyzes an unusual glycosylation reaction that results in the addition of GlcNAc in an N-glycosidic linkage to arginine 117 (R117) of FADD (8, 9). This modification prevents death domain interactions between FADD and Fas and subsequent assembly of the canonical death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) (8, 9). Since the discovery of this modification, another example of arginine glycosylation has been identified; in that case, the bacterial glycosyltransferase EarP rhamnosylates translation elongation factor P to activate its function (24).

Apart from the DXD catalytic motif of NleB1, little is known about other functional sites in the protein and the regions required for substrate binding and specificity. Unlike the human O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which possesses N-terminal tetratricopeptide (TPR) repeats necessary for substrate binding (25–27), NleB1 appears to lack such a motif. In this study, we screened transposon (Tn) and site-directed mutants of NleB1 to identify functional regions of NleB1. We found that both Tyr219 and Glu253 were essential for the enzymatic activity of NleB1 and its virulence function during infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The E. coli and Citrobacter rodentium strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with shaking or in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) without shaking. When required, the following antibiotics were added at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml or 100 μg/ml; nalidixic acid (Nal), 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 10 μg/ml or 25 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 12.5 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR [ϕ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] | 60 |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| BL21 C41 (DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm λ (DE3) [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 Sam7 nin-5]) | Novagen |

| EPEC E2348/69 | Wild-type EPEC O127:H6 | 61 |

| EPEC E2348/69 ΔnleB1 | E2348/69 ΔnleB1::Cm (Cmr) | 9 |

| EPEC E2348/69 ΔescN | E2348/69 ΔescN::Kan (Kanr) | 62 |

| C. rodentium | ||

| ICC169 | Spontaneous Nalr derivative of wild-type C. rodentium biotype 4280 | 63 |

| ΔnleB | ICC169 ΔnleB::Kan (Nalr Kanr) | 9 |

DNA cloning and purification.

The plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. PCR products or restriction digests were purified from agarose gels using a Wizard SV gel and PCR cleanup system (Promega). Plasmids were isolated using a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen) or a NucleoBondXtra midikit (Macherey-Nagel) per the manufacturers' instructions. Restriction enzyme digests were performed using enzymes and buffers from NEB according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ligation reactions were performed at an insert/vector molar ratio of 4:1 at room temperature (RT) overnight using T4 DNA ligase (NEB) per the manufacturer's instructions.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pEGFP-C2 | Expression vector carrying EGFP fused to the N terminus of the partner protein, Kanr | Clontech |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1 | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1P63A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid P63 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1I64A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid I64 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1L65A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid L65 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1N66A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid N66 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1K68A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid K68 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1K81A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid K81 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1D93A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid D93 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1D121A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid D121 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1D128A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid D128 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1L157A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid L157 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1Y219A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid Y219 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1Y234A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid Y234 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1P236A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid P236 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1D237A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid D237 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1G238A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid G238 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1I239A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid I239 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1H242A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid H242 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1E253A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid E253 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1N263A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid N263 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1L267A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid L267 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1A269E | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid A269 mutated to E, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1Y283A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid Y238 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1K292A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with amino acid K292 mutated to A, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the PILN(63–66) motif mutated to AAAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1HKQ(140–142)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the HKQ(140–142) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1QES(142–144)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the QES(142–144) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1LGLL(155–158)AAAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the LGLL(155–158) motif mutated to AAAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1GSL(197–199)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the GSL(197–199) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1DXD(221–223)AXA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the DXD(221–223) catalytic motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | 9 |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1DKL(228–230)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the DKL(228–230) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the PDG(236–238) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1SN(262–263)AA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with SN(262–263) motif mutated to AA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1LAGL(268–271)AEAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the LAGL(268–271) motif mutated to AEAA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1KV(277–278)AA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the KV(277–278) motif mutated to AA, Kanr | This study |

| pEGFP-C2-NleB1KGI(289–291)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pEGFP-C2 with the KGI(289–291) motif mutated to AAA, Kanr | This study |

| pTrc99A | Low-copy-no. bacterial expression vector with inducible lacI promoter, Ampr | Pharmacia Biotech |

| pTrc99A-NleB1 | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pTrc99A, Ampr | 6 |

| pTrc99A-NleB1DXD(221–223)AXA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pTrc99A with the DXD(221–223) catalytic motif mutated to AXA, Ampr | 9 |

| pTrc99A-NleB1Y219A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pTrc99A with amino acid Y219 mutated to A, Ampr | This study |

| pTrc99A-NleB1E253A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pTrc99A with amino acid E253 mutated to A, Ampr | This study |

| pGEX-4T-1 | Low-copy-no. N-terminal glutathione S-transferase fusion vector, Ampr | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX-NleB1 | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pGEX-4T-1, Ampr | 9 |

| pGEX-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pGEX-4T-1 with the PILN(63–66) motif mutated to AAAA, Ampr | This study |

| pGEX-NleB1Y219A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pGEX-4T-1 with amino acid Y219 mutated to A, Ampr | This study |

| pGEX-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pGEX-4T-1 with PDG(236–238) motif mutated to AAA, Ampr | This study |

| pGEX-NleB1E253A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pGEX-4T-1 with amino acid E253 mutated to A, Ampr | This study |

| pET28a(+) | Low-copy-no. bacterial expression vector carrying an N-terminal His6 tag, Kanr | Novagen |

| pET28a-FADD | Full-length FADD in pET28a(+), Kanr | 9 |

| pFLAG-FADD | Full-length FADD in p3×FLAG-Myc-CMV-24, Ampr | Ashley Mansell |

| pCX340 | Cloning vector used to construct C-terminal TEM-1 β-lactamase fusions, Tetr | 31 |

| pTEM-NleB1 | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pCX340, Tetr | This study |

| pTEM-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pCX340 with the PILN(63–66) motif mutated to AAAA, Tetr | This study |

| pTEM-NleB1Y219A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pCX340 with amino acid Y219 mutated to A, Tetr | This study |

| pTEM-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pCX340 with the PDG(236–238) motif mutated to AAA, Tetr | This study |

| pTEM-NleB1E253A | nleB1 from EPEC E2348/69 in pCX340 with amino acid E253 mutated to A, Tetr | This study |

| pACYC184 | Medium-copy-no. cloning vector, Cmr Tetr | NEB |

| pACYC184-NleBCR | nleB from C. rodentium ICC169 in pACYC184, Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-NleBY219ACR | nleB from C. rodentium ICC169 in pACYC184 with amino acid Y219 mutated to A, Cmr | This study |

| pACYC184-NleBE253ACR | nleB from C. rodentium ICC169 in pACYC184 with amino acid E253 mutated to A, Cmr | This study |

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer namea | Primer sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| pEGFP-C2 F | AACACCCCCATCGGCG |

| pEGFP-C2 R | GTAACCATTATAAGCTGC |

| NotI | TGCGGCCGCA |

| pTrc99A F | CGGTTCTGGCAAATATTC |

| pTrc99A R | GCAGTTCCCTACTCTCGC |

| P63A Fb | GCGATACGAAAAAGGAGAAGTAGCAATATTGAATACCAAAGAACATCCG |

| P63A Rb | CGGATGTTCTTTGGTATTCAATATTGCTACTTCTCCTTTTTCGTATCGC |

| I64A Fb | GCGATACGAAAAAGGAGAAGTACCAGCATTGAATACCAAAGAACATCCG |

| I64A Rb | CGGATGTTCTTTGGTATTCAATATTGCTACTTCTCCTTTTTCGTATCGC |

| L65A Fb | GCGATACGAAAAAGGAGAAGTACCAATAGCGAATACCAAAGAACATCCGTATTTG |

| L65A Rb | CAAATACGGATGTTCTTTGGTATTCGCTATTGGTACTTCTCCTTTTTCGTATCGC |

| N66A Fb | GATACGAAAAAGGAGAAGTACCAATATTGGCTACCAAAGAACATCCGTATTTGAGC |

| N66A Rb | GCTCAAATACGGATGTTCTTTGGTAGCCAATATTGGTACTTCTCCTTTTTCGTATC |

| K68A Fb | GAAGTACCAATATTGAATACCGCAGAACATCCGTATTTGAGC |

| K68A Rb | GCTCAAATACGGATGTTCTGCGGTATTCAATATTGGTACTTC |

| K81A Fb | GAGCAATATTATAAATGCTGCAGCAATAGAAAATGAGCGTATAATCGG |

| K81A Rb | CCGATTATACGCTCATTTTCTATTGCTGCAGCATTTATAATATTGCTC |

| D93A Fb | GTATAATCGGTGTGCTGGTAGCTGGAAATTTTACTTATGAACAAAAAAAG |

| D93A Rb | CTTTTTTTGTTCATAAGTAAAATTTCCAGCTACCAGCACACCGATTATAC |

| D121A Fb | CAAAATATAAAAATAATCTACCGAGCAGCTGTGGATTTCAGCATGTATG |

| D121A Rb | CATACATGCTGAAATCCACAGCTGCTCGGTAGATTATTTTTATATTTTG |

| D128A Fb | CAGATGTGGATTTCAGCATGTATGCTAAAAAACTATCTGATATTTAC |

| D128A Rb | GTAAATATCAGATAGTTTTTTAGCATACATGCTGAAATCCACATCTG |

| L157A Fb | GAGGGATAATTATCTGTTAGGCGCATTAAGAGAAGAGTTAAAAAATATCC |

| L157A Rb | GGATATTTTTTAACTCTTCTCTTAATGCGCCTAACAGATAATTATCCCTC |

| Y219A Fb | CGCCCTGTAGCGGATGTATAGCTCTTGATGCCGACATGATTATTAC |

| Y219A Rb | GTAATAATCATGTCGGCATCAAGAGCTATACATCCGCTACAGGGCG |

| Y234A Fb | CCGATAAATTAGGAGTCCTGGCTGCTCCTGATGGTATCGCTGTG |

| Y234A Rb | CACAGCGATACCATCAGGAGCAGCCAGGACTCCTAATTTATCGG |

| P236A Fb | GGAGTCCTGTATGCTGCTGATGGTATCGCTGTGC |

| P236A Rb | GCACAGCGATACCATCAGCAGCATACAGGACTCC |

| D237A Fb | GGAGTCCTGTATGCTCCTGCTGGTATCGCTGTGCATGTAG |

| D237A Rb | CTACATGCACAGCGATACCAGCAGGAGCATACAGGACTCC |

| G238A Fb | GGAGTCCTGTATGCTCCTGATGCTATCGCTGTGCATGTAG |

| G238A Rb | CTACATGCACAGCGATAGCATCAGGAGCATACAGGACTCC |

| I239A Fb | GGAGTCCTGTATGCTCCTGATGGTGCCGCTGTGCATGTAG |

| I239A Rb | CTACATGCACAGCGGCACCATCAGGAGCATACAGGACTCC |

| H242A Fb | CTCCTGATGGTATCGCTGTGGCTGTAGATTGTAATGATGAG |

| H242A Rb | CTCATCATTACAATCTACAGCCACAGCGATACCATCAGGAG |

| E253A Fb | GTGGATTGTAATGATAATAGAAAAAGTCTTGCAAATGGTGCAATAGTTGTCAATC |

| E253A Rb | GATTGACAACTATTGCACCATTTGCAAGACTTTTTCTATTATCATTACAATCCAC |

| N263A Fb | GTCAATCGTAGTGCTCATCCAGCATTACTTGCAGGCCTCGATATTATG |

| N263A Rb | CATAATATCGAGGCCTGCAAGTAATGCTGGATGAGCACTACGATTGAC |

| L267A Fb | GTAATCATCCAGCAGCACTTGCAGGCCTCGATATTATGAAGAG |

| L267A Rb | CTCTTCATAATATCGAGGCCTGCAAGTGCTGCTGGATGATTAC |

| A269E Fb | GTAATCATCCAGCATTACTTGAAGGCCTCGATATTATGAAGAG |

| A269E Rb | CTCTTCATAATATCGAGGCCTTCAAGTAATGCTGGATGATTAC |

| Y283A Fb | GTAAAGTTGACGCTCATCCAGCTTATGATGGTCTAGGAAAGGG |

| Y283A Rb | CCCTTTCCTAGACCATCATAAGCTGGATGAGCGTCAACTTTAC |

| K292A Fb | GATGGTCTAGGAAAGGGTATCGCGCGGCATTTTAACTATTCATCG |

| K292A Rb | CGATGAATAGTTAAAATGCCGCGCGATACCCTTTCCTAGACCATC |

| PILN Fb | GCGATACGAAAAAGGAGAAGTAGCAGCAGCGGCTACCAAAGAACATCCGTATTTG |

| PILN Rb | CAAATACGGATGTTCTTTGGTAGCCGCTGCTGCTACTTCTCCTTTTTCGTATCGC |

| HKQ Fb | CTGATATTTACCTTGAAAATATCGCTGCAGCAGAATCATACCCTGCCAGTGAGAGGG |

| HKQ Rb | CCCTCTCACTGGCAGGGTATGATTCTGCTGCAGCGATATTTTCAAGGTAAATATCAG |

| QES Fb | CCTTGAAAATATCCATAAAGCAGCAGCATACCCTGCCAGTGAGAGGG |

| QES Rb | CCCTCTCACTGGCAGGGTATGCTGCTGCTTTATGGATATTTTCAAGG |

| LGLL Fb | CAGTGAGAGGGATAATTATCTGGCAGCCGCAGCAAGAGAAGAGTTAAAAAATATCCCAGAAGG |

| LGLL Rb | CCTTCTGGGATATTTTTTAACTCTTCTCTTGCTGCGGCTGCCAGATAATTATCCCTCTCACTG |

| GSL Fb | GGCCATATTGAAGGCTGCAGCTGCGTTTACAGAGACGGGAAAAACTGG |

| GSL Rb | CCAGTTTTTCCCGTCTCTGTAAACGCAGCTGCAGCCTTCAATATGGCC |

| DKL Fb | GCCGACATGATTATTACCGCTGCAGCAGGAGTCCTGTATGCTCCTG |

| DKL Rb | CAGGAGCATACAGGACTCCTGCTGCAGCGGTAATAATCATGTCGGC |

| PDG Fb | GATAAATTAGGAGTCCTGTATGCTGCTGCTGCTATCGCTGTGCATGTAGATTG |

| PDG Rb | CAATCTACATGCACAGCGATAGCAGCAGCAGCATACAGGACTCCTAATTTATC |

| SN Fb | GGTGCGATAGTTGTCAATCGTGCTGCTCATCCAGCATTACTTGC |

| SN Rb | GCAAGTAATGCTGGATGAGCAGCACGATTGACAACTATCGCACC |

| LAGL Fb | GTCAATCGTAGTAATCATCCAGCATTAGCTGAAGCCGCCGATATTATGAAGAGTAAAGTTGACGC |

| LAGL Rb | GCGTCAACTTTACTCTTCATAATATCGGCGGCTTCAGCTAATGCTGGATGATTACTACGATTGAC |

| KV Fb | GGCCTCGATATTATGAAGAGTGCAGCTGACGCTCATCCATATTATG |

| KV Rb | CATAATATGGATGAGCGTCAGCTGCACTCTTCATAATATCGAGGCC |

| KGI Fb | CATCCATATTATGATGGTCTAGGAGCGGCTGCCAAGCGGCATTTTAACTATTCATCG |

| KGI Rb | CGATGAATAGTTAAAATGCCGCTTGGCAGCCGCTCCTAGACCATCATAATATGGATG |

| B1 F | CCGGTACCATGTTATCTTCATTAAATGTCC |

| B1 R | C GGAATTCCC CCATGAACTGCTGGTATAC |

| pCX340 F | AAGGCGCACTCCCGTTC |

| pCX340 R | GTCATTCTGAGAATAGTG |

| pGEX F | CGTATTGAAGCTATCCCACAA |

| pGEX R | GGGAGCTGCATGTGTCAGAG |

| pGEX B1 F | CGCGAATTCATGTTATCTTCATTAAATGTCCTTC |

| pGEX B1 R | CGCGTCGACTTACCATGAACTGCTGGTATAC |

| CR B F | CGGGATCCGGATAAACAGGACGACGAATGTTATCTCCATTAAATGTTCTTCAATTTAATTTC |

| CR B R | CGGTCGACTTACCATGAACTGTTGGTATACATACTGG |

| pACYC seq F | GTACTGCCGGGCCTCTTG |

| pACYC seq R | GAAGGCTTGAGCGAGGGCG |

| CR Y219A F | CTCCATGTGGGGGATGTATAGCTCTTGATGCAGATATGATTATTAC |

| CR Y219A R | GTAATAATCATATCTGCATCAAGAGCTATACATCCCCCACATGGAG |

| CR E253A F | GTGGATTGTAATGATAATAGAAAAAGTCTTGCAAATGGTGCAATAGTTGTCAATC |

| CR E253A R | GATTGACAACTATTGCACCATTTGCAAGACTTTTTCTATTATCATTACAATCCAC |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Primers used to introduce site-directed mutations in nleB1. The primer name is indicative of the amino acid mutation(s) introduced in NleB1.

Construction of nleB1 insertion mutants.

Generation of a library of nleB1 transposon mutants was carried out using an F-701 mutation generation system kit (Life Technologies). The transposon mutants were generated in a pEGFP-C2-NleB1 clone following the manufacturer's instructions, whereby EPEC E2348/69 nleB1 was cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. Following transformation of the transposition reaction in E. coli, the transformants were plated onto Luria-Bertani agar (LA) containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol to select for pEGFP-C2-NleB1 constructs carrying artificial transposons carrying a chloramphenicol resistance (Camr) marker gene (M1-Camr), designated entranceposons, and pooled for plasmid extraction. To ensure the generation of mutations only in the nleB1 gene and not in the vector backbone, plasmids were digested with EcoRI and BamHI to release nleB1 containing the entranceposon. The mutated nleB1 was purified and ligated into newly extracted pEGFP-C2 that had been digested with the same pair of enzymes. The product of the ligation reaction was transformed into E. coli, and isolates carrying the construct were selected on LA plates containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol.

Plasmids were extracted from the transformants and digested with the restriction enzyme NotI to remove the body of the entranceposon. The NotI-digested clones were self-ligated, resulting in a 15-bp insertion in the nleB1 gene. The 15-bp insertion in the coding region of nleB1 is translated into 5 extra amino acids. The position of the pentapeptide insertion of each mutant was determined by PCR with the primer pairs pEGFP-C2 F/NotI and NotI/pEGFP-C2 R, and the exact position was determined by sequencing with primer pair pEGFP-C2 F/R. Each mutant nleB1 from the pEGFP-C2 constructs was then digested with EcoRI and BamHI, purified, and ligated into the pTrc99A vector. The ligation reaction constructs were individually transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue cells, and the plasmid extracts were further sequenced with the primer pair pTrc99A F/R.

Construction of nleB1 site-directed mutants.

A library of site-directed mutants of nleB1 was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using the pEGFP-C2-NleB1 clone and a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, pEGFP-C2-NleB1 was used as the template in the PCRs to generate the single and multiple site-directed mutations in NleB1 fused to an N-terminal enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) tag. The primer pairs used to introduce the site-directed mutations in NleB1 are listed in Table 3. The PCR mixtures were digested with the DpnI restriction enzyme at 37°C overnight before subsequent transformation of the products of the PCRs into E. coli XL1-Blue cells. Plasmids extracted from transformants were sequenced with pEGFP-C2 F/R. The constructs pTrc99A-NleB1Y219A and pTrc99A-NleB1E253A were obtained by digesting the corresponding pEGFP-C2 constructs with EcoRI and BamHI and ligation into pTrc99A.

Cloning of EPEC E2348/69 nleB1 and mutants into pCX340 to express C-terminal TEM-1 fusions for β-lactamase translocation assays.

The wild-type EPEC E2348/69 nleB1 gene was amplified from genomic DNA using the primer pair B1 F/R. The PCR product was then purified and digested with KpnI and EcoRI, before ligation into pCX340. The product of the ligation reaction was transformed into E. coli DH5α cells. Colonies were used as the template with the primer pair pCX340 F/R in a colony PCR, and positive clones were picked for plasmid extraction and sequencing by use of the same primer pair. The pCX340-NleB1 mutants were obtained by first amplifying mutated nleB1 using the primer pair B1 F/R and the construct pEGFP-C2-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, pEGFP-C2-NleB1Y219A, pEGFP-C2-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, or pEGFP-C2-NleB1E253A as the template. The PCR products were purified and digested with KpnI and EcoRI, before ligation into pCX340. Ligation of the correct insert was verified by colony PCR and sequencing with the primer pair pCX340 F/R.

Cloning of EPEC E2348/69 nleB1 mutants into pGEX-4T-1 to express N-terminal GST-tagged fusion proteins.

Plasmids expressing N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged NleB1 mutants GST-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, GST-NleB1Y219A, GST-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, and GST-NleB1E253A were constructed by amplifying mutated nleB1 using the constructs pEGFP-C2-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, pEGFP-C2-NleB1Y219A, pEGFP-C2-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, and pEGFP-C2-NleB1E253A, respectively, as the templates and the primer pair pGEX-B1 F/R. The amplicons, which were approximately 1 kb, were digested with EcoRI and SalI and ligated into pGEX-4T-1. The products of the ligation reactions were transformed into XL1-Blue cells. Insertion of the correct insert into the vector pGEX-4T-1 was verified by colony PCR using the primer pair pGEX F/R and by sequencing.

Construction of pACYC184 derivatives for use in mouse experiments.

The wild-type nleB gene from C. rodentium ICC169 was amplified from genomic DNA using the primer pair CR B F/R. The PCR product, which was approximately 1 kb and which was flanked by the BamHI and SalI sites, was digested with the previously mentioned restriction enzymes and ligated behind the tetracycline promoter of the vector pACYC184. The product of the ligation reaction was transformed into XL1-Blue cells. Ligation of the correct insert into the vector pACYC184 was verified by colony PCR using the primer pair pACYC seq F/R and by sequencing. The mutations Y219A and E253A were generated in the C. rodentium NleB protein using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit as described above, the correct pACYC184-CR NleB construct as the template, and the primer pairs CR Y219A F/R and CR E253A F/R, respectively.

Bioinformatics analysis.

A multiple-sequence alignment of the amino acid sequence of the region surrounding the DXD motif of EPEC E2348/69 NleB1 (residues 176 to 230; GenBank accession number CAS10779) with the amino acid sequences of different bacterial glycosyltransferases, including Legionella pneumophila Lgt1 (Lpg1319 [residues 209 to 260; PDB accession number 2WZG] and Lpg1368 [residues 209 to 260; GenBank accession number Q5ZVS2]), Clostridium novyi alpha toxin (residues 253 to 296; GenBank accession number Q46149), Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin (LT; residues 255 to 298; GenBank accession number Q46342), Clostridium difficile toxins A and B (residues 253 to 299 [GenBank accession number CAC03681] and residues 255 to 298 [GenBank accession number P18177], respectively), and Photorhabdus asymbiotica protein toxin (PaTox; residues 2245 to 2290; GenBank accession number CAQ84322), was generated using the MUSCLE (version 3.5) alignment tool (28) through the Geneious (version 8.1.4) tool (29).

Screening of a library of NleB1 transposon mutants by detection of cleaved caspase-8 by immunoblotting.

For detection of cleaved caspase-8 during EPEC infection, HeLa cells were infected with various EPEC derivatives and then stimulated with the Fas ligand (FasL) to induce host cell apoptosis by the extrinsic pathway before collection and analysis of cell lysates. Briefly, on the day before tissue culture infection, HeLa cells were seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells/ml in 24-well plates (Greiner Bio One) and the various EPEC derivatives were cultured in 10 ml LB broth overnight at 37°C. On the following day, the bacterial cultures were subinoculated 1:75 in DMEM and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2.5 h before the induction of NleB1 protein expression from the Ptrc promoter with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for another 30 min. HeLa cells were infected with the various EPEC strains for 2 h and treated with 100 μg/ml gentamicin with or without 20 ng/ml of FasL (Andreas Strasser, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research, Victoria, Australia) for a further 2 to 3 h. HeLa cells were lysed and subjected to gel electrophoresis, and then the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated for at least 16 h at 4°C with rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved caspase-8 antibodies (Asp391; antibody clone 18C8; Cell Signaling) diluted 1:1,000 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween 20 (Chem-Supply) or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibodies (catalog number AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:5,000 in TBS with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% Tween 20. Proteins were detected using anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Perkin-Elmer) and developed with the ECL Prime Western blotting reagent (Amersham). All secondary antibodies were diluted 1:3,000 in TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20. Images were visualized using an MFChemiBis imaging station (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems).

Screening of a library of site-directed mutants of NleB1 by immunoprecipitation of FLAG-FADD and immunoblotting.

HEK293T cells were seeded at approximately 5 × 105 cells/ml in 10-cm dishes (Corning) and were cotransfected with pEGFP-C2-NleB1 or its derivative site-directed mutants together with pFLAG-FADD using the FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, at 16 to 24 h after transfection, the cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 600 μl cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (1 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 15 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% deoxycholate) containing 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete; Mini; EDTA free; Roche), 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cell debris was pelleted, the supernatant was collected, and 70 μl of the supernatant was kept as the input protein. The remaining cell lysate was applied to equilibrated anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads, and the mixture was incubated on a rotating wheel at 4°C overnight. The beads were magnetically separated and washed 3 times with cold 1× RIPA lysis buffer, and the protein was eluted with 100 μg/ml FLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich). The beads were magnetically separated, the supernatants (immunoprecipitates [IPs]) along with the input samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis, and the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed as necessary with the primary antibodies mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (clones 7.1 and 13.1; Roche), mouse monoclonal anti-GlcNAc (antibody CTD 110.6; Cell Signaling), or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (antibody AC15; Sigma), diluted 1:2,000, 1:1,000, and 1:5,000, respectively, in TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20. The immunoblots were then washed 3 times and probed with HRP-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies diluted 1:3,000 in TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 before they were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare). The membranes were probed with mouse anti-FLAG-HRP antibodies (Sigma) diluted 1:1,000, washed, and developed. Antibody binding was visualized using an MFChemiBis imaging station.

Preparation of GST- and His-tagged proteins.

Overnight cultures of BL21(pGEX-4T-1), BL21(pGEX-NleB1), BL21(pGEX-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA), BL21(pGEX-NleB1Y219A), BL21(pGEX-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA), BL21(pGEX-NleB1E253A), and BL21(pET28a-FADD) cells grown in LB broth were diluted 1:100 in 200 ml of LB broth supplemented with either kanamycin (for the pET construct) or ampicillin (for the pGEX constructs) with shaking to an optical density (OD) of 0.6 at 37°C. The bacterial cultures were incubated with 1 mM IPTG, grown for a further 2 h, and then pelleted by centrifugation. Bacterial cells were lysed using an EmulsiFlex-C3 high-pressure homogenizer (Avestin). Proteins were purified by either nickel or glutathione affinity chromatography in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Novagen). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific).

Incubation of GST- and His-tagged proteins.

Two micrograms of purified recombinant proteins was incubated either alone or in combination in distilled water at 37°C for 4 h in the presence of 1 mM UDP-GlcNAc (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were subsequently probed with the primary antibodies mouse monoclonal anti-GlcNAc (antibody CTD 110.6; Cell Signaling), which recognizes O-linked and N-linked GlcNAc (30); rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (Cell Signaling); or mouse monoclonal anti-His (antibody AD1.1.10; AbD Serotech), diluted 1:1,000, 1:1,000, and 1:2,000, respectively, in TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20. The immunoblots were then washed 3 times and probed with either HRP-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies or goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibodies diluted 1:3,000 in TBS with 5% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 before they were developed with ECL Western blotting detection reagents. Images were visualized using an MFChemiBis imaging station.

β-Lactamase translocation assay.

The translocation of effector proteins from EPEC was measured by using translational fusions to TEM-1 β-lactamase (31). Translocation in living host cells was detected directly by using a fluorescent β-lactamase substrate, CCF2/AM. Cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS and infected with bacterial cultures at a starting OD at 600 nm of 0.03 for 2 h. The cells were then loaded with CCF2/AM dye (β-lactamase loading solutions; Life Technologies) for 1.5 h in the dark, before being replaced with Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2.5 mM probenecid in 0.12 M sodium dihydrogen orthophosphate, pH 8.0. The blue emission fluorescence (450 nm) and green emission fluorescence (520 nm) were measured on a CLARIOstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech), and the translocation signal was shown as the ratio of blue emission fluorescence to green emission fluorescence.

Infection of mice with Citrobacter rodentium.

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Melbourne Animal Ethics Committee (ethics approval number 1413406.5). Bacterial strains were cultured in LB broth containing antibiotics, as required, overnight at 37°C with shaking. On the following day, the bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,220 × g for 10 min at RT, and the bacterial cell pellet was then resuspended in PBS. Unanesthetized 5- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were each given 200 μl of a bacterial suspension containing approximately 2 × 109 CFU in PBS by oral gavage. The viable count of the inoculum was determined by retrospective serial dilution and plating on LA containing the required antibiotic. A minimum of 5 mice per group was used, and the experiment was repeated three times. Mice were weighed every 2 days after inoculation and monitored. Fecal samples were collected aseptically from each mouse on various days up to 14 days after inoculation and emulsified in PBS at a final concentration of 100 mg/ml. The number of viable bacteria per gram of feces was determined by plating serial dilutions of the samples onto antibiotic selective medium. The limit of detection was 40 CFU/g feces.

RESULTS

Screening of transposon mutants of NleB1 for loss of function.

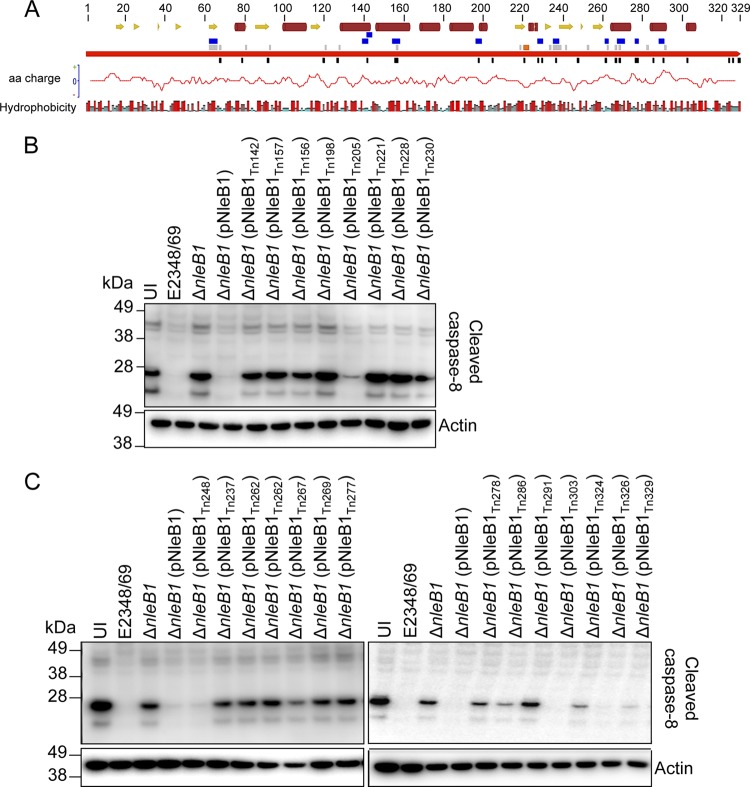

In order to gain insight into the functional regions of NleB1, a plasmid carrying NleB1 (pEGFP-C2-NleB1) was mutated using the bacteriophage MuA transposase. Artificial transposons carrying a chloramphenicol resistance marker gene, designated entranceposons (M1-Camr), were randomly inserted into the target plasmid in vitro. The plasmids obtained from the transformants were digested with NotI and closed by self-ligation to remove the body of the entranceposon. This resulted in a 15-bp insertion in the nleB1 gene encoding 5 additional amino acids. The exact position of the pentapeptide insertion of each mutant was determined by sequencing. This system yielded 27 insertion mutants of NleB1, 2 of which contained a pentapeptide insertion between amino acids 261 and 262 with different sequences (Fig. 1A; Table 4). Derivatives of nleB1 carrying the 15-bp insertions were cloned into pTrc99A in order to test the library of mutants during EPEC infection. The insertion mutants were then screened for their ability to inhibit caspase-8 activation during EPEC infection.

FIG 1.

Mutagenesis of NleB1 and screen of NleB1 transposon mutants for loss of function. (A) Schematic diagram mapping the transposon insertion sites and the positions of single or multiple site-directed mutations in NleB1. Continuous red arrow, NleB1; orange box, the catalytic DXD region; black boxes, transposon insertion sites; gray and blue boxes, single and multiple site-directed mutations, respectively. The secondary structure of NleB1 was predicted by use of the Jnet program (59). Yellow arrows, β sheets; dark red cylinders, α helices. The amino acid polarity graph was plotted by use of the EMBOSS charge tool through the Geneious program, and the hydrophobicity of each residue is shown below the NleB1 protein. Amino acid (aa) residues are colored from red through blue according to the hydrophobicity value, where red is the most hydrophobic and blue is the most hydrophilic. (B and C) Immunoblots showing cleaved caspase-8 in HeLa cells infected with EPEC derivatives that carry the pTrc99A vector backbone with different NleB1 insertion mutations and that were stimulated with FasL. Cells were harvested for immunoblotting, and cleaved caspase-8 was detected with anti-cleaved caspase-8 antibodies. Antibodies to β-actin were used as a loading control. The immunoblots are representative of those from at least three independent experiments. Lanes UI, uninfected.

TABLE 4.

EPEC derivatives and their effect on caspase-8 activation during EPEC infection

| EPEC strain genotypea | Pentapeptide insertion sequence | Caspase-8 activationb |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | − | − |

| ΔnleB1 | − | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1) | − | − |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn68) | NAAAT | NTc |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn79) | AAAAN | NT |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn92) | VAAAL | NT |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn120) | AAAAR | NT |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn127) | YAAAM | NT |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn142) | CGRNK | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn156) | GAAAL | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn157) | CGRIG | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn198) | CGRTG | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn205) | CGRTG | + |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn221) | DAAAL | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn228) | DAAAT | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn230) | CGRNK | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn237) | DAAAP | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn248) | CGRND | − |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn262) | MRPHR | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn262) | SAAAR | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn267) | CGRTA | + |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn269) | AAAAL | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn277) | CGRKS | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn278) | CGRSK | ++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn286) | CGRND | + |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn291) | IAAAG | +++ |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn303) | CGRNN | − |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn324) | CGRSM | + |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn326) | SAAAT | − |

| ΔnleB1(pNleB1Tn329) | LRPHS | + |

The number after Tn indicates the position of the insertion.

HeLa cell lysates were examined for caspase-8 activation levels after EPEC infection and FasL stimulation; +, ++, and +++, increasing levels of caspase-8 cleavage, with +++ indicating levels of caspase-8 cleavage comparable to that of uninfected HeLa cells stimulated with FasL; −, the absence of caspase-8 cleavage comparable to the inhibition observed in the presence of wild-type NleB1.

NT, not tested.

HeLa cells were infected with various EPEC derivatives, including wild-type strain EPEC E2348/69, E2348/69 ΔnleB1 carrying pTrc99A, and E2348/69 ΔnleB1 complemented with wild-type nleB1 or an nleB1 insertion mutant derivative carried by pTrc99A. Caspase-8 activation was then induced by treatment with FasL. All nleB1 mutants were tested for their ability to block caspase-8 activation, except for 5 mutants which likely carried an insertion into the N-terminal translocation signal of NleB1 (32–35). Caspase-8 activation was assessed by immunoblotting using an antibody that recognizes only cleaved (activated) caspase-8. As expected, complementation of the ΔnleB1 mutant with wild-type nleB1 resulted in inhibition of caspase-8 activation to a level similar to that observed in cells infected with wild-type strain EPEC E2348/69 (Fig. 1B and C) (9). Of the 22 insertion mutants tested, 14 did not inhibit caspase-8 cleavage, including nleB1Tn221 (where 221 indicates the position of Tn insertion) carrying an insertion in the catalytic DXD region (residues 221 to 223) (Fig. 1B and C; Table 4). In addition, both nleB1Tn262 mutants appeared to be equally unable to inhibit caspase-8 activation, irrespective of the pentapeptide sequence introduced between amino acids 261 and 262.

Site-directed mutagenesis of NleB1 and screening of site-directed mutants of NleB1 for loss of function.

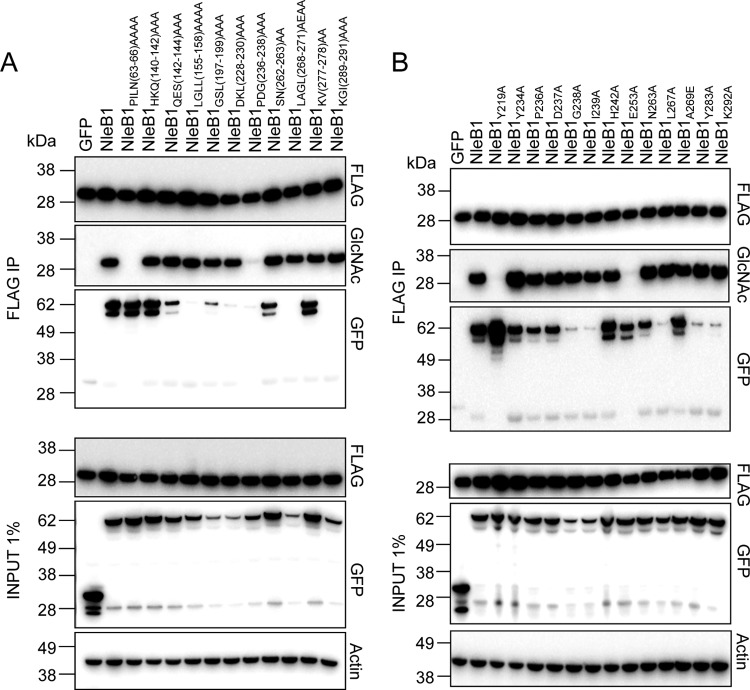

To examine potential functional regions of NleB1 further, a total of 34 mutants with amino acid substitutions were constructed using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit in plasmid pEGFP-C2-NleB1; 23 of these were mutants with single amino acid substitutions, and 11 were mutants with multiple amino acid substitutions (Fig. 1A; Table 5). The change of Glu253 to Ala (E253A) was also chosen for evaluation, as previous work showed that this mutation impaired the ability of NleB1 to inhibit NF-κB activation upon tumor necrosis factor stimulation (8). Ten of the 34 amino acid substitutions (9 single amino acid substitutions and 1 multiple amino acid substitution) were created in the N terminus of NleB1, as this region was not examined in the caspase-8 screening assay, which required the translocation of NleB1 and, hence, the N-terminal translocation signal. Site-directed mutants were then tested for their ability to GlcNAcylate FADD. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing derivatives of GFP-tagged NleB1 and FLAG-FADD before FLAG-FADD was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates. The immunoprecipitates (IPs) were then examined for GlcNAcylation of FADD using an antibody to GlcNAc and for coimmunoprecipitation of GFP-tagged NleB1 derivatives (Fig. 2; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Site-directed mutants of NleB1 and their effect on FADD GlcNAcylation and binding

| Mutant | Ability to GlcNAcylate FADDa | Binding to FADDa |

|---|---|---|

| NleB1 single-site-directed mutants | ||

| P63A | +++ | +++ |

| I64A | +++ | +++ |

| L65A | +++ | +++ |

| N66A | +++ | +++ |

| K68A | +++ | +++ |

| K81A | +++ | +++ |

| D93A | +++ | + |

| D121A | +++ | +++ |

| D128A | +++ | − |

| L157A | +++ | + |

| Y219A | − | +++ |

| Y234A | +++ | +++ |

| P236A | +++ | +++ |

| D237A | +++ | +++ |

| G238A | +++ | + |

| I239A | +++ | + |

| H242A | +++ | +++ |

| E253A | − | +++ |

| N263A | +++ | +++ |

| L267A | +++ | + |

| A269E | +++ | +++ |

| Y283A | +++ | + |

| K292A | +++ | + |

| NleB1 multiple-site-directed mutants | ||

| PILN(63–66)AAAA | − | +++ |

| HKQ(140–142)AAA | +++ | +++ |

| QES(142–144)AAA | +++ | ++ |

| LGLL(155–158)AAAA | +++ | − |

| GSL(197–199)AAA | +++ | + |

| DKL(228–230)AAA | +++ | − |

| PDG(236–238)AAA | + | − |

| SN(262–263)AA | +++ | ++ |

| LAGL(268–271)AEAA | +++ | − |

| KV(277–278)AA | +++ | +++ |

| DAD(221–223)AAA | − | +++ |

| KGI(289–291)AAA | +++ | − |

+, ++, and +++, increasing levels of FADD GlcNAcylation or binding, with +++ reflecting the level of FADD GlcNAcylation or binding observed in the presence of wild-type NleB1; −, an absence of FADD GlcNAcylation or binding

FIG 2.

Screening of NleB1 site-directed mutants for loss of GlcNAcylation activity toward FADD. (A and B) Immunoblots of inputs and IPs of anti-FLAG immunoprecipitations performed on lysates of HEK293T cells cotransfected with pFLAG-FADD and pEGFP-C2-NleB1 (GFP-NleB1) or the pEGFP-C2 constructs carrying the site-directed mutants of NleB1. The FLAG-FADD IPs were tested for GlcNAcylation by immunoblotting with anti-GlcNAc antibodies. GFP-NleB1 and the mutants were tested for coimmunoprecipitation with FLAG-FADD by immunoblotting of the IPs with anti-GFP antibodies. Antibodies to β-actin were used as a loading control. The immunoblots are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

The catalytic mutant NleB1DXD(221–223)AXA was unable to GlcNAcylate FADD, although it still bound FADD (Table 5). One mutant of NleB1 with multiple-site-directed mutations, NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA (Fig. 2A), and two mutants of NleB1 with single-site-directed mutations, NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A (Fig. 2B), were also unable to GlcNAcylate FADD, and another mutant with multiple-site-directed mutations, NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, showed a reduced ability to GlcNAcylate FADD (Fig. 2A). The loss-of-function mutants NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, NleB1Y219A, and NleB1E253A still bound to FADD, whereas the NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA mutant did not interact with FADD (Fig. 2). NleB1 carrying the mutations D93A, L157A, GSL(197–199)AAA, G238A, I239A, L267A, Y283A, and K292A bound weakly to FADD (Fig. 2; Table 5), whereas NleB1 carrying the mutations D128A, LGLL(155–158)AAAA, DKL(228–230)AAA, LAGL(268–271)AEAA, and KGI(289–291)AAA did not appear to bind FADD. However, all these mutants still mediated FADD GlcNAcylation, suggesting that NleB1-substrate interactions need not be stable and long lasting for GlcNAcylation to occur (Fig. 2; Table 5). GFP-NleB1 or the derivative mutants that bound FADD appeared as doublets on the immunoblots probed with anti-GFP, possibly reflecting protein degradation at the C terminus during immunoprecipitation.

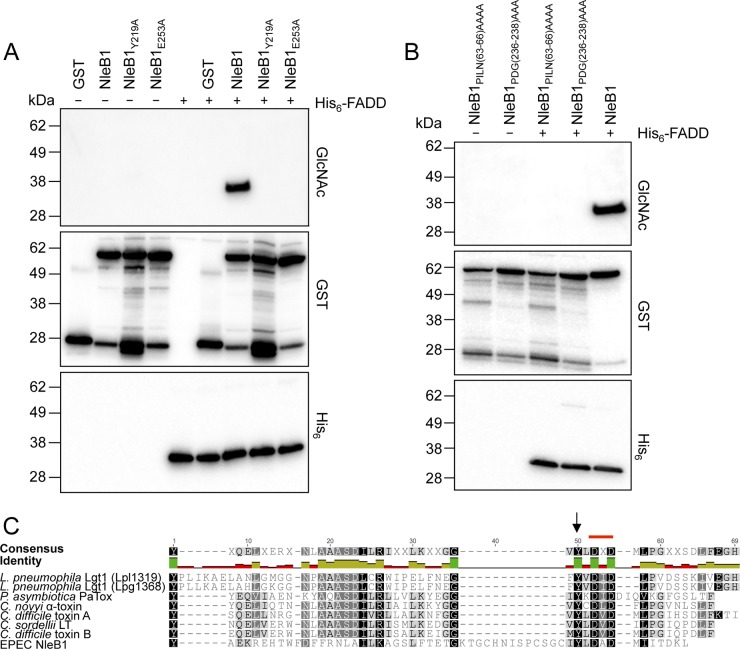

In vitro, NleB1 GlcNAcylates FADD directly in the presence of the sugar donor, UDP-GlcNAc. To confirm the loss of function of four NleB1 mutants [NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, NleB1Y219A, NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, and NleB1E253A], recombinant NleB1 proteins with an N-terminal GST tag and recombinant FADD with an N-terminal His6 tag were purified and incubated either alone or together in the presence of UDP-GlcNAc. The incubation mixtures were separated by gel electrophoresis, and the gels were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane that was probed with antibodies to GlcNAc, GST, and His6. Whereas incubation of GST-NleB1 and His6-FADD with UDP-GlcNAc led to FADD GlcNAcylation, this was not observed when GST-NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, GST-NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, GST-NleB1E253A, or GST-NleB1Y219A was used (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG 3.

Loss of enzymatic activity of NleB1 mutants. (A and B) Immunoblots of recombinant protein incubation mixtures from an in vitro assay for NleB1-mediated GlcNAc modification of FADD. Recombinant GST-NleB1 or the mutants and His-FADD were incubated alone or together in the presence of 1 mM UDP-GlcNAc. GlcNAcylation of FADD was tested by immunoblotting with anti-GlcNAc antibodies, and the presence of the GST and His fusion proteins was detected by immunoblotting with anti-GST and anti-His antibodies. The immunoblots are representative of those from at least three independent experiments. (C) Sequence similarity of the NleB1 central region with the catalytic region of glycosyltransferases from Clostridium, Legionella, and Photorhabdus species. A multiple-sequence alignment of the amino acid sequence of the region surrounding the DXD motif (marked with a red line) of EPEC E2348/69 NleB1 (residues 176 to 236; GenBank accession number CAS10779) with different bacterial glycosyltransferases was generated using MUSCLE (28) through the Geneious tool (29). The glycosyltransferases included Legionella pneumophila Lgt1 (Lpl1319 [residues 209 to 260; PDB accession number 2WZG] and Lpg1368 [residues 209 to 260; GenBank accession number Q5ZVS2]), Photorhabdus asymbiotica PaTox (residues 2245 to 2290; GenBank accession number CAQ84322), Clostridium novyi alpha toxin (residues 253 to 296; GenBank accession number Q46149), Clostridium sordellii LT (residues 255 to 298; GenBank accession number Q46342), Clostridium difficile toxin A (residues 253 to 299; GenBank accession number CAC03681), and Clostridium difficile toxin B (residues 255 to 298; GenBank accession number P18177). Black arrow, the Tyr219 residue in EPEC NleB1 conserved in the other glycosyltransferases. The weighted shading of the highlights indicates the percent similarity of the aligned residues, with darker colors indicating the highest conservation. The identity across all sequences for every residue is displayed above the aligned sequences: green, the residue at the given position is the same across all sequences; yellow, less than complete identity; red, very low identity for the given position. Hyphens indicate gaps inserted by Geneious on the basis of the Blosum62 substitution matrix to generate the alignment.

Conservation of tyrosine-219 (Y219) in glycosyltransferases from Clostridium, Legionella, and Photorhabdus species.

Although NleB1 shares little homology with proteins of known function at the primary amino acid sequence level, NleB1 was first proposed to be a glycosyltransferase by in silico fold recognition (36). Here we compared the NleB1 amino acid sequence with empirically established three-dimensional structures using the FUGUE program (37). FUGUE identified NleB1 to be an unambiguous structural homologue of the Photorhabdus asymbiotica protein toxin (PaTox) (FUGUE Z-score, 4.43; 95% confidence). In addition to causing disease in insects, P. asymbiotica is an emerging human pathogen (38). PaTox was recently identified to be a glycosyltransferase targeting eukaryotic Rho GTPases, thereby inhibiting Rho activation and causing host cell death (39). When the region around the catalytic site of PaTox was compared to that of glycosylating toxins from Clostridium species and L. pneumophila, several residues around the DXD triad were conserved (39). Hence, we compared the catalytic region of NleB1 to that of PaTox, L. pneumophila glucosyltransferase 1 (Lgt1), alpha toxin of Clostridium novyi, LT of Clostridium sordellii, and toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile using the MUSCLE alignment tool (28). This showed a number of conserved amino acids, including the DXD motif and the tyrosine residue equivalent to Y219 of NleB1, suggesting the importance of Y219 in the enzymatic function of NleB1 (Fig. 3C).

Effect of loss-of-function mutations NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A on FADD GlcNAcylation during EPEC infection.

Ectopically expressed and recombinant NleB1 with the single amino acid substitution Y219A or E253A was unable to modify FADD, even though it still bound to its target (Fig. 2B and 3A). To study the effects of these mutations on NleB1 function during infection, we first verified that NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A were translocated into host cells by the T3SS. Translational fusions of NleB1 and mutant derivatives to TEM-1 β-lactamase were generated using the vector pCX340, and the fusion proteins were introduced into the ΔnleB1 and ΔescN mutants. Expression of the fusion proteins in EPEC was detected by immunoblotting using antibodies to β-lactamase and NleB1 (data not shown). Following infection, NleB1 translocation was detected in HeLa cells by using the CCF2/AM fluorescent substrate and measuring the blue/green emission ratio as described previously (40). In contrast to the NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA and NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA mutant derivatives, both the NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A mutant derivatives were translocated by the T3SS to wild-type levels (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Effect of the Y219A and E253A mutations on NleB1 translocation from EPEC and caspase-8 activation during infection. (A) Translocation of NleB1 derivatives NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, NleB1Y219A, and NleB1E253A fused to TEM-1 from EPEC ΔnleB1. Results are the means ± SEMs from three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. Significant differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple-comparison test. ***, P < 0.0001. (B) Immunoblot showing cleaved caspase-8 in HeLa cells infected with EPEC derivatives that expressed the different NleB1 mutants [NleB1DXD(221–223)AxA, NleB1Y219A, NleB1E253A] from the pTrc99A vector backbone and that were stimulated with FasL. Cells were harvested for immunoblotting, and cleaved caspase-8 was detected with anti-cleaved caspase-8 antibodies. Antibodies to β-actin were used as a loading control. The immunoblots are representative of those from at least three independent experiments.

To determine if the NleB1Y219A or NleB1E253A delivered by the T3SS blocked caspase-8 cleavage in response to FasL stimulation, HeLa cells were infected with wild-type EPEC E2348/69, E2348/69 ΔnleB1, or E2348/69 ΔnleB1 complemented with nleB1, nleB1 encoding the Y219A substitution, or nleB1 encoding the E253A substitution. As shown previously, caspase-8 cleavage was prevented during infection with wild-type EPEC E2348/69, whereas it was not with the ΔnleB1 mutant (Fig. 4B) (9), and complementation of the ΔnleB1 mutant with wild-type nleB1 restored the inhibition of caspase-8 cleavage. None of the NleB1DXD(221–223)AxA, NleB1Y219A, or NleB1E253A mutant derivatives was able to inhibit caspase-8 cleavage.

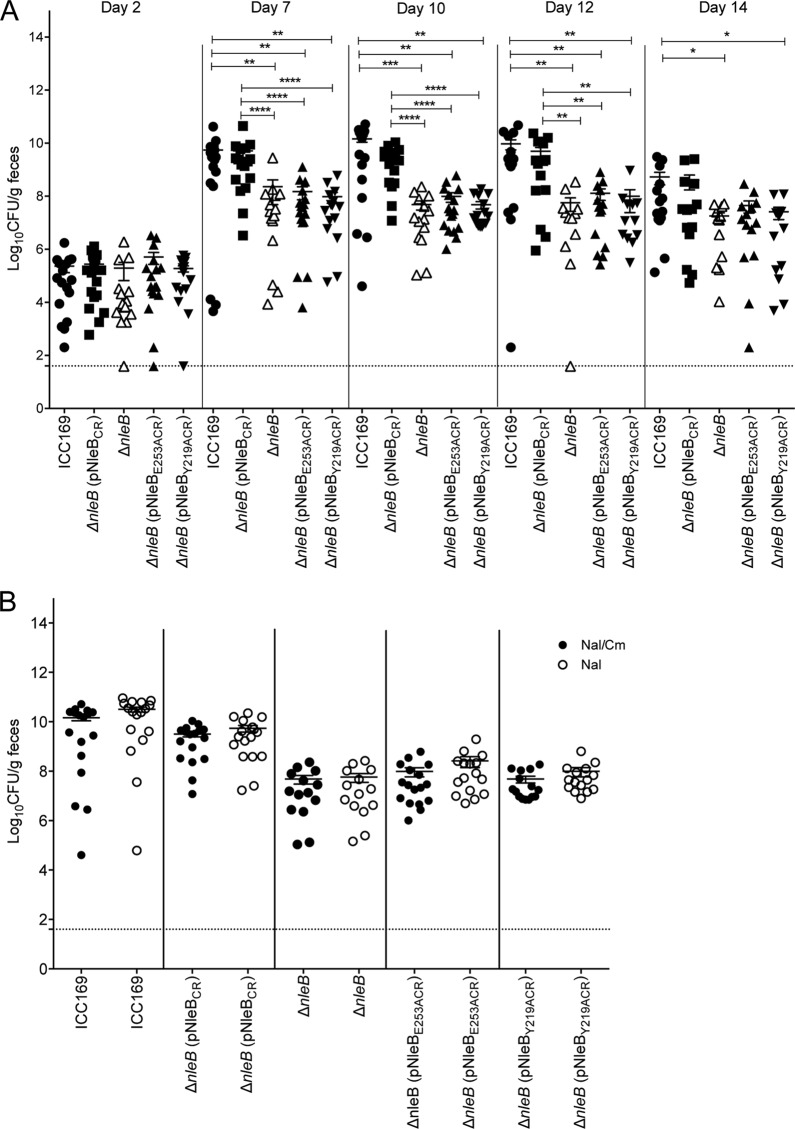

Amino acid residues Y219 and E253 are required for NleB function during Citrobacter rodentium infection of mice.

Mice infected with the EPEC-like mouse pathogen C. rodentium are widely used as a small-animal model of EPEC infection. NleB from C. rodentium is needed for the full colonization of mice (41), and NleB from C. rodentium has been shown to GlcNAcylate several death domain proteins, including FADD, TRADD, and RIPK1 (8). Since amino acid residues Y219 and E253 are conserved in C. rodentium NleB, we investigated whether NleBY219A and NleBE253A could complement the function of NleB in vivo. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were inoculated orally with wild-type C. rodentium carrying pACYC184, the isogenic ΔnleB mutant carrying pACYC184, or ΔnleB carrying pACYC184 harboring wild-type C. rodentium nleB, nleB encoding the Y219A substitution, or nleB encoding the E253A substitution. Fecal samples were collected on days 2, 7, 10, 12, and 14, and the number of viable bacteria (number of CFU) per gram of feces was determined. No differences in the fecal numbers of CFU of C. rodentium were observed between the 5 groups of mice on day 2 following infection (Fig. 5A). However, on days 7, 10, and 12, the level of colonization by the ΔnleB mutant carrying pACYC184 was significantly lower than that by wild-type C. rodentium carrying pACYC184 or the ΔnleB mutant complemented with wild-type nleB (Fig. 5A). This finding is consistent with previous findings showing that NleB is required for virulence in mice (9, 41). Neither the nleB mutant encoding the Y219A substitution nor the nleB mutant encoding the E253A substitution was able to restore the colonization ability of the ΔnleB mutant, indicating that these amino acids are essential for the virulence function of NleB in vivo (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

Residues Y219 and E253 in Citrobacter rodentium NleB are important for intestinal colonization. (A) Colonization of C57BL/6 mice with the indicated C. rodentium derivatives. Each data point represents the log10 number of CFU per gram of feces per individual animal on days 2, 7, 10, 12, and 14 postinfection. Means ± SEMs are indicated. Dotted line, detection limit. Significant differences were determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Comparison of viable counts of C. rodentium derivatives from fecal samples collected on day 10 postinfection on LA supplemented with nalidixic acid (Nal) and chloramphenicol (Cm) versus LA supplemented with nalidixic acid only to determine the extent of pACYC loss in vivo.

To ensure that the lower levels of colonization by the ΔnleB mutant carrying pACYC184 harboring the nleB mutant encoding Y219A or the nleB mutant encoding E253A were not due to the loss of the complementation vectors by the ΔnleB mutant, fecal samples were collected from each group and plated on Luria-Bertani agar containing nalidixic acid (Nal) and chloramphenicol (Cm) (selecting for C. rodentium and pACYC184) or Nal only (selecting for C. rodentium) on day 10 after infection. No differences in the fecal numbers of CFU from each group were observed, indicating that carriage of the pACYC184 plasmid derivatives was stable (Fig. 5B).

DISCUSSION

The initial suggestion that NleB was a glycosyltransferase stemmed from a fold prediction performed using the HHpred protein structure prediction tool (36). Subsequently, NleB1 was shown to bind and modify death domain-containing proteins, including FADD, TRADD, and RIPK1, by the addition of GlcNAc to a conserved arginine in the death domain of these proteins (8, 9). By preventing assembly of the DISC upon death receptor stimulation, NleB1 mediates a strong antiapoptotic effect in the host cell during EPEC infection.

Other than the DXD motif from residues 221 to 223 and E253 (8), the specific amino acid residues and regions of NleB that participate in this unusual biochemical activity were unknown. To identify additional functional regions of NleB1, in the present study a library of insertion mutants of NleB1 was screened for the ability to inhibit caspase-8 activation during EPEC infection of HeLa cells. Of the 22 insertion mutants tested, 17 did not inhibit FasL-induced caspase-8 cleavage. The regions around these pentapeptide insertions were investigated further by site-directed mutagenesis. However, few of these amino acid substitutions resulted in a loss of function. The disparity between the high number of insertion mutants that lost their ability to inhibit FasL-induced caspase-8 cleavage during EPEC infection and the smaller number of site-directed mutants that lost enzymatic activity may reflect the greater structural changes introduced by the pentapeptide insertion and/or the limitation of using as a screen caspase-8 cleavage during infection, which relied on the efficient translocation of the NleB1 insertion mutants by the EPEC T3SS.

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments with ectopically expressed GFP-NleB1 mutants and FLAG-FADD and incubation of recombinant GST-NleB1 mutant proteins and His6-FADD in the presence of UDP-GlcNAc revealed that four mutant derivatives [NleB1PILN(63–66)AAAA, NleB1PDG(236–238)AAA, NleB1Y219A, and NleB1E253A] were unable to GlcNAcylate FADD. Interestingly, a number of NleB1 amino acid substitutions that led to weak or no binding to FADD still showed efficient GlcNAcylation. One possible explanation for this is that the mutations affected the substrate binding stability and activity kinetics so that a transient interaction was sufficient for GlcNAcylation to occur. Of the four site-directed NleB1 mutants that did not GlcNAcylate FADD, only the NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A mutants were translocated into HeLa cells during EPEC infection, and hence, these were studied further. Despite this, the regions of NleB1 encompassing PILN(63–66) and PDG(236–238) should not be disregarded as potential functional regions of NleB1. Although it is potentially located in the T3SS translocation signal, PILN(63–66) may also be important for the enzymatic activity of NleB1, since the mutant with these mutations bound but did not modify FADD. This is in contrast to PDG(236–238), where mutation of this region led to a loss of FADD binding and GlcNAcylation.

It is generally accepted that the actions of glycosyltransferases follow a sequential ordered mechanism, whereby a metal ion and the sugar donor substrate bind first, resulting in a conformational change that creates the acceptor substrate binding site (42–48). For example, both the mammalian glycosyltransferase β4Gal-T1 and the bacterial Neisseria meningitidis enzyme LgtC have 2 flexible loops which act as a lid covering the bound sugar substrate, exposing a binding site for the acceptor substrate (49–51). Detailed structural analysis of NleB1 will help to define the role of PILN(63–66) in any conformational shift upon UDP-GlcNAc binding, whereas PDG(236–238) may be important for acceptor substrate binding, since mutation of this region inhibited both FADD modification and binding.

Interestingly, residue Y219 of NleB1 is highly conserved among glycosyltransferase toxins and effectors from Clostridium spp. and L. pneumophila. The equivalent tyrosine residue, Y284, in C. difficile toxin B was identified by protein crystallography and mutagenesis to be necessary for glycosyltransferase activity (52, 53). The strong reduction in the enzymatic activity of the Y284A toxin B mutant was not attributed to an impaired sugar donor substrate interaction, given the distance between the hydroxyl group of Y284 and that of the ribose of the sugar donor (52). Instead, it was postulated that Y284A was required to position D286 from the DXD motif for its interaction with the catalytic metal cation Mn2+ (52). However, it is still possible that Y219 in NleB1 interacts with UDP-GlcNAc by hydrophobic π stacking, as observed for numerous aromatic side chain-containing amino acids (39, 54, 55). Alternatively, Y219 in NleB1 may interact with UDP-GlcNAc via hydrogen bonding, as the equivalent tyrosine in C. difficile toxin A (Y283) is positioned in close proximity to two carbonyls of the ribose ring and a water molecule (56, 57).

Although E253 is highly conserved among the NleB/SseK effectors (58), it is not found in other glycosyltransferases and may be involved in the unusual ability of NleB to glycosylate arginine. However, in the absence of empirical structural information, the function of E253 in NleB enzymatic activity is unknown. Both the NleB1Y219A and NleB1E253A mutants lost their ability to inhibit FasL-induced caspase-8 cleavage in vitro. Additionally, C. rodentium strains expressing NleBY219A and NleBE253A showed significantly reduced intestinal colonization compared to that of C. rodentium expressing wild-type NleB. Altogether, these findings show that Y219 and E253 are essential for the activity of NleB1 both in vitro and in vivo and confirm that FADD GlcNAcylation and not just FADD binding is critical for the function of NleB1 in virulence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Ashley Mansell (Hudson Medical Research Institute, Australia) and Andreas Strasser (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research, Victoria, Australia) for the gifts of pFLAG-FADD and FasL, respectively.

T.W.F.L. and Y.Z. are recipients of a University of Melbourne International Research Scholarship (MIRS), and C.G. and G.L.P. are recipients of an Australian Postgraduate Award (APA). K.C. is supported by a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) research fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng W, Puente JL, Gruenheid S, Li Y, Vallance BA, Vazquez A, Barba J, Ibarra JA, O'Donnell P, Metalnikov P, Ashman K, Lee S, Goode D, Pawson T, Finlay BB. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400326101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giogha C, Wong Fok Lung T, Pearson JS, Hartland EL. 2014. Inhibition of death receptor signaling by bacterial gut pathogens. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 25:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong AR, Pearson JS, Bright MD, Munera D, Robinson KS, Lee SF, Frankel G, Hartland EL. 2011. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: even more subversive elements. Mol Microbiol 80:1420–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadler C, Baruch K, Kobi S, Mills E, Haviv G, Farago M, Alkalay I, Bartfeld S, Meyer TF, Ben-Neriah Y, Rosenshine I. 2010. The type III secretion effector NleE inhibits NF-κB activation. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000743. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton HJ, Pearson JS, Badea L, Kelly M, Lucas M, Holloway G, Wagstaff KM, Dunstone MA, Sloan J, Whisstock JC, Kaper JB, Robins-Browne RM, Jans DA, Frankel G, Phillips AD, Coulson BS, Hartland EL. 2010. The type III effectors NleE and NleB from enteropathogenic E. coli and OspZ from Shigella block nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB p65. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Ding X, Cui J, Xu H, Chen J, Gong YN, Hu L, Zhou Y, Ge J, Lu Q, Liu L, Chen S, Shao F. 2012. Cysteine methylation disrupts ubiquitin-chain sensing in NF-κB activation. Nature 481:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nature10690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, Zhang L, Yao Q, Li L, Dong N, Rong J, Gao W, Ding X, Sun L, Chen X, Chen S, Shao F. 2013. Pathogen blocks host death receptor signalling by arginine GlcNAcylation of death domains. Nature 501:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson JS, Giogha C, Ong SY, Kennedy CL, Kelly M, Robinson KS, Wong Fok Lung T, Mansell A, Riedmaier P, Oates CV, Zaid A, Mühlen S, Crepin VF, Marchès O, Ang CS, Williamson NA, O'Reilly LA, Bankovacki A, Nachbur U, Infusini G, Webb AI, Silke J, Strasser A, Frankel G, Hartland EL. 2013. A type III effector antagonizes death receptor signalling during bacterial gut infection. Nature 501:247–251. doi: 10.1038/nature12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breton C, Snajdrova L, Jeanneau C, Koca J, Imberty A. 2006. Structures and mechanisms of glycosyltransferases. Glycobiology 16:29R–37R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lairson LL, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, Withers SG. 2008. Glycosyltransferases: structures, functions, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biochem 77:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061005.092322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belyi Y, Aktories K. 2010. Bacterial toxin and effector glycosyltransferases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jank T, Giesemann T, Aktories K. 2007. Rho-glucosylating Clostridium difficile toxins A and B: new insights into structure and function. Glycobiology 17:15R–22R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voth DE, Ballard JD. 2005. Clostridium difficile toxins: mechanism of action and role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:247–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.247-263.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehrman MA. 1991. Biosynthesis of N-acetylglucosamine-P-P-dolichol, the committed step of asparagine-linked oligosaccharide assembly. Glycobiology 1:553–562. doi: 10.1093/glycob/1.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou TY, Hart GW, Dang CV. 1995. c-Myc is glycosylated at threonine 58, a known phosphorylation site and a mutational hot spot in lymphomas. J Biol Chem 270:18961–18965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hart GW. 1997. Dynamic O-linked glycosylation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 66:315–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole RN, Hart GW. 1999. Glycosylation sites flank phosphorylation sites on synapsin I: O-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues are localized within domains mediating synapsin I interactions. J Neurochem 73:418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng X, Cole RN, Zaia J, Hart GW. 2000. Alternative O-glycosylation/O-phosphorylation of the murine estrogen receptor beta. Biochemistry 39:11609–11620. doi: 10.1021/bi000755i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comer FI, Hart GW. 2000. O-Glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Dynamic interplay between O-GlcNAc and O-phosphate. J Biol Chem 275:29179–29182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi KJ, Grass S, Paek S, St Geme JW III, Yeo HJ. 2010. The Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae HMW1C-like glycosyltransferase mediates N-linked glycosylation of the Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin. PLoS One 5:e15888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grass S, Lichti CF, Townsend RR, Gross J, St Geme JW III. 2010. The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1C protein is a glycosyltransferase that transfers hexose residues to asparagine sites in the HMW1 adhesin. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000919. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross J, Grass S, Davis AE, Gilmore-Erdmann P, Townsend RR, St Geme JW III. 2008. The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin is a glycoprotein with an unusual N-linked carbohydrate modification. J Biol Chem 283:26010–26015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801819200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lassak J, Keilhauer EC, Fürst M, Wuichet K, Gödeke J, Starosta AL, Chen JM, Sogaard-Andersen L, Rohr J, Wilson DN, Häussler S, Mann M, Jung K. 2015. Arginine-rhamnosylation as new strategy to activate translation elongation factor P. Nat Chem Biol 11:266–270. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jinek M, Rehwinkel J, Lazarus BD, Izaurralde E, Hanover JA, Conti E. 2004. The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin alpha. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11:1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreppel LK, Blomberg MA, Hart GW. 1997. Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem 272:9308–9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubas WA, Frank DW, Krause M, Hanover JA. 1997. O-Linked GlcNAc transferase is a conserved nucleocytoplasmic protein containing tetratricopeptide repeats. J Biol Chem 272:9316–9324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isono T. 2011. O-GlcNAc-specific antibody CTD110.6 cross-reacts with N-GlcNAc2-modified proteins induced under glucose deprivation. PLoS One 6:e18959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charpentier X, Oswald E. 2004. Identification of the secretion and translocation domain of the enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli effector Cif, using TEM-1 β-lactamase as a new fluorescence-based reporter. J Bacteriol 186:5486–5495. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5486-5495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mudgett MB, Chesnokova O, Dahlbeck D, Clark ET, Rossier O, Bonas U, Staskawicz BJ. 2000. Molecular signals required for type III secretion and translocation of the Xanthomonas campestris AvrBs2 protein to pepper plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230450797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sory MP, Boland A, Lambermont I, Cornelis GR. 1995. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:11998–12002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.11998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lara-Tejero M, Kato J, Wagner S, Liu X, Galan JE. 2011. A sorting platform determines the order of protein secretion in bacterial type III systems. Science 331:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.1201476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SH, Galan JE. 2004. Salmonella type III secretion-associated chaperones confer secretion-pathway specificity. Mol Microbiol 51:483–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao X, Wang X, Pham TH, Feuerbacher LA, Lubos ML, Huang M, Olsen R, Mushegian A, Slawson C, Hardwidge PR. 2013. NleB, a bacterial effector with glycosyltransferase activity, targets GAPDH function to inhibit NF-κB activation. Cell Host Microbe 13:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi J, Blundell TL, Mizuguchi K. 2001. FUGUE: sequence-structure homology recognition using environment-specific substitution tables and structure-dependent gap penalties. J Mol Biol 310:243–257. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerrard J, Waterfield N, Vohra R, ffrench Constant R. 2004. Human infection with Photorhabdus asymbiotica: an emerging bacterial pathogen. Microbes Infect 6:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jank T, Bogdanovic X, Wirth C, Haaf E, Spoerner M, Böhmer KE, Steinemann M, Orth JH, Kalbitzer HR, Warscheid B, Hunte C, Aktories K. 2013. A bacterial toxin catalyzing tyrosine glycosylation of Rho and deamidation of Gq and Gi proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:1273–1280. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mills E, Baruch K, Charpentier X, Kobi S, Rosenshine I. 2008. Real-time analysis of effector translocation by the type III secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell Host Microbe 3:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly M, Hart E, Mundy R, Marches O, Wiles S, Badea L, Luck S, Tauschek M, Frankel G, Robins-Browne RM, Hartland EL. 2006. Essential role of the type III secretion system effector NleB in colonization of mice by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect Immun 74:2328–2337. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2328-2337.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boix E, Swaminathan GJ, Zhang Y, Natesh R, Brew K, Acharya KR. 2001. Structure of UDP complex of UDP-galactose:beta-galactoside-alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase at 1.53-Å resolution reveals a conformational change in the catalytically important C terminus. J Biol Chem 276:48608–48614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flint J, Taylor E, Yang M, Bolam DN, Tailford LE, Martinez-Fleites C, Dodson EJ, Davis BG, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. 2005. Structural dissection and high-throughput screening of mannosylglycerate synthase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:608–614. doi: 10.1038/nsmb950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qasba PK, Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E. 2005. Substrate-induced conformational changes in glycosyltransferases. Trends Biochem Sci 30:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon RD, Sivarajah P, Satkunarajah M, Ma D, Tarling CA, Vizitiu D, Withers SG, Rini JM. 2006. X-ray crystal structures of rabbit N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I (GnT I) in complex with donor substrate analogues. J Mol Biol 360:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubota T, Shiba T, Sugioka S, Furukawa S, Sawaki H, Kato R, Wakatsuki S, Narimatsu H. 2006. Structural basis of carbohydrate transfer activity by human UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (pp-GalNAc-T10). J Mol Biol 359:708–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramakrishnan B, Ramasamy V, Qasba PK. 2006. Structural snapshots of beta-1,4-galactosyltransferase-I along the kinetic pathway. J Mol Biol 357:1619–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziegler MO, Jank T, Aktories K, Schulz GE. 2008. Conformational changes and reaction of clostridial glycosylating toxins. J Mol Biol 377:1346–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gastinel LN, Cambillau C, Bourne Y. 1999. Crystal structures of the bovine beta4galactosyltransferase catalytic domain and its complex with uridine diphosphogalactose. EMBO J 18:3546–3557. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Persson K, Ly HD, Dieckelmann M, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG, Strynadka NC. 2001. Crystal structure of the retaining galactosyltransferase LgtC from Neisseria meningitidis in complex with donor and acceptor sugar analogs. Nat Struct Biol 8:166–175. doi: 10.1038/84168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramasamy V, Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E, Qasba PK. 2003. The role of tryptophan 314 in the conformational changes of beta1,4-galactosyltransferase-I. J Mol Biol 331:1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jank T, Giesemann T, Aktories K. 2007. Clostridium difficile glucosyltransferase toxin B—essential amino acids for substrate binding. J Biol Chem 282:35222–35231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reinert DJ, Jank T, Aktories K, Schulz GE. 2005. Structural basis for the function of Clostridium difficile toxin B. J Mol Biol 351:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]