SUMMARY

Many genes that affect replicative lifespan (RLS) in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae also affect aging in other organisms such as C. elegans and M. musculus. We performed a systematic analysis of yeast RLS in a set of 4,698 viable single-gene deletion strains. Multiple functional gene clusters were identified, and full genome-to-genome comparison demonstrated a significant conservation in longevity pathways between yeast and C. elegans. Among the mechanisms of aging identified, deletion of tRNA exporter LOS1 robustly extended lifespan. Dietary restriction (DR) and inhibition of mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) exclude Los1 from the nucleus in a Rad53-dependent manner. Moreover, lifespan extension from deletion of LOS1 is non-additive with DR or mTOR inhibition, and results in Gcn4 transcription factor activation. Thus, the DNA damage response and mTOR converge on Los1-mediated nuclear tRNA export to regulate Gcn4 activity and aging.

Keywords: S. cerevisiae, lifespan, aging, los1, tRNA transport, Rad53, mTOR

INTRODUCTION

Aging has long fascinated and puzzled biologists (Haldane, 1942; Medawar, 1952). In most organisms, a decline in fitness occurs over time that coincides with increased incidence of several significant causes of morbidity and mortality (Mayeux and Stern, 2012; Simms, 1946). With modern forward and reverse genetic techniques, several groups have shown that single genes can have a dramatic effect on lifespan (Guarente and Kenyon, 2000), and many of these have been found to act together in known signaling pathways (Fontana et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2013; Kenyon, 2010; Lapierre and Hansen, 2012). Further, the onset of many disadvantageous late life phenotypes is delayed in many long-lived mutant organisms (Garigan et al., 2002; Herndon et al., 2002; Morley et al., 2002).

In yeast, aging can be assayed by at least two methods: chronological lifespan (CLS) and replicative lifespan (RLS) (Kaeberlein, 2010; Longo et al., 2012). The yeast RLS assay measures how many daughter cells a mother can produce before it ceases dividing, and has been proposed as an assay to identify conserved pathways affecting the continued viability of dividing cells such as stem cells in humans (Steinkraus et al., 2008). A partial genome-to-genome comparison indicated that genes controlling RLS in yeast overlapped with those influencing aging in worms (Smith et al., 2008), which are post-mitotic after adulthood. With the goal of extending this finding to a full genome-to-genome comparison and identifying conserved aging genes, we completed a full genome screen of viable S. cerevisiae deletions, identifying 238 long-lived gene deletions, including 189 not previously reported. These cluster into several functional groups, including ribosomal proteins, the SAGA complex, mannosyltransferase genes, and genes involved in TCA cycle metabolism, among others.

These functional clusters may overlap, or otherwise be linked, especially for a process as complex as aging. One link established by our labs centered around Gcn4; this transcription factor was not only critical for RLS extension by reduced 60S translation, but also for a mitochondrial protease gene deletion afg3Δ (Delaney et al., 2012). Our screen identified another unexpected link, again involving Gcn4. DNA damaging agents such as methyl methane sulfonate (MMS) were shown to inhibit the Los1 tRNA transporter by excluding it from the nucleus, leading to Gcn4 activation. This effect on Los1 required checkpoint response factor Rad53 (Ghavidel et al., 2007). Deletion of LOS1 extended RLS in our screen, and we chose to further define this mechanism of RLS extension based on the possibility that understanding it might connect DNA damage signaling to translational regulation of lifespan.

RESULTS

Genome-scale identification of single-gene deletions that extend yeast replicative lifespan

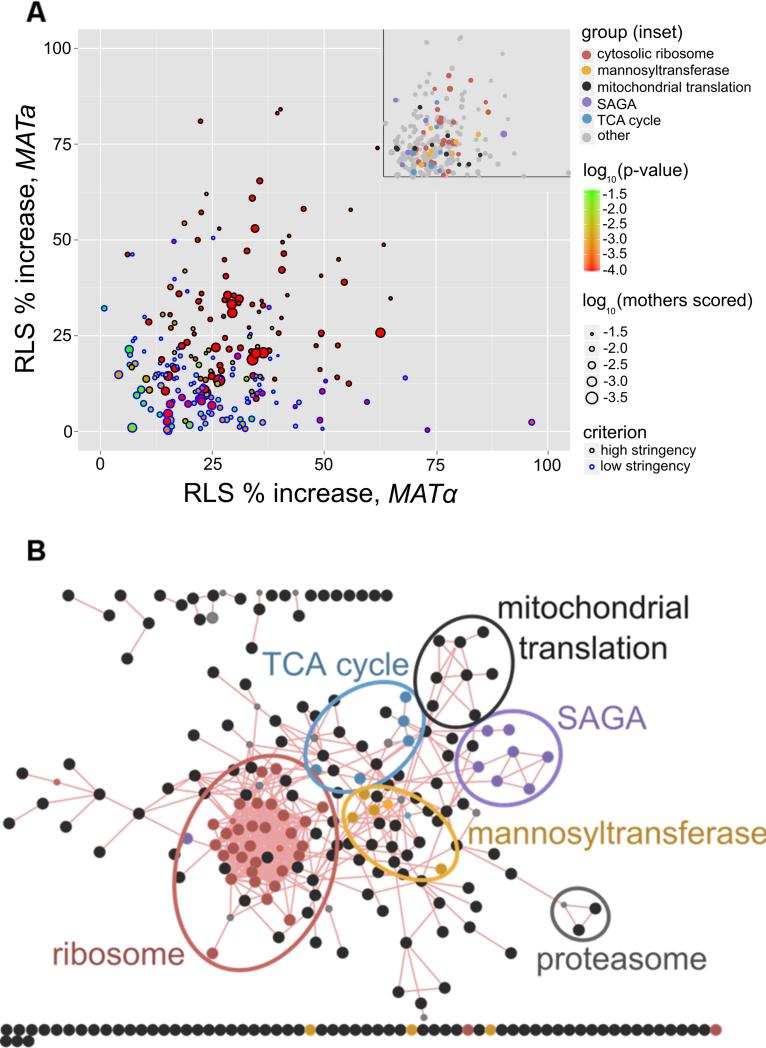

We performed a genome-wide analysis of viable S. cerevisiae single-gene deletions by measuring the RLS of 5 mother cells in the MATα mating type for 4,698 unique strains, based on the approach outlined previously (Kaeberlein and Kennedy, 2005). For each strain that showed a mean RLS increase of >30% over control, or p<0.05 for increased RLS, we measured RLS for 20 cells in the MATa strain carrying the same gene deletion. For all gene deletions that extended RLS significantly in both mating types, at least 20 mother cells total were scored in each mating type. In some cases of divergent mating type RLS, the difference may be due to the selection of slow-growth suppressors in the non-long-lived mating type, as has been observed for ribosomal protein mutants (Steffen et al., 2012). In cases where we have observed a changed RLS upon reconstruction of the strain, only reconstructed data is included. We have observed zero examples in this data where a significant difference between mating types survived reconstruction of the strains, and also note that the very large number of mother cells scored for wild type MATa and MATα show no significant difference in RLS. A graphical summary of all long-lived deletions found in this screen is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

A. Summary of RLS data for long-lived deletion strains. Axes indicate % increase in RLS relative to control in MATa and MATα respectively. Point size is proportional to number of mother cells scored, and point color indicates p-value for increased RLS relative to control. Point outline indicates stringency for inclusion: high stringency cutoff was p<0.05 for Wilcoxon rank-sum increased survival independently in both mating types, and low stringency was p<0.05 for pooled data from both mating types with increased RLS shown in each mating type alone. B. Functional clustering of long-lived deletions. Large circles represent long-lived deletions; edges are published physical protein-protein interactions. Overrepresented categories noted in color; p<0.05 with Holm-Bonferroni multiple testing correction.

Statistical criteria are summarized in Supplemental Methods, and tested strains are listed in Supplemental Table S1, related to Figure 1. 238 long-lived deletion strains are summarized in Supplemental Table S2, related to Figure 1, and complete survival curves and graphical survival by functional group are shown in Supplemental Figure S1, related to Figure 1. Mortality analysis for all long-lived strains with over 200 scored mother cells is shown in Supplemental Figure S2, related to Figure 1.

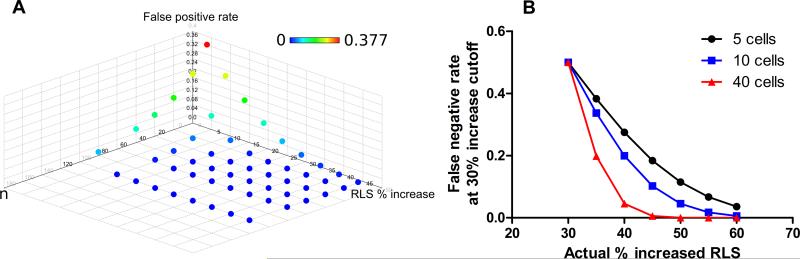

The over 780,000 individual manually dissected wild-type yeast daughter cells in this project provide a high resolution for making accurate estimates of false positive and negative rates, allowing us to estimate the total fraction of viable yeast deletions likely to affect RLS. We generated sampling distributions from our wild-type cells (Supplemental Figure S3, related to Figure 2 and Supplemental Methods). Using these, we estimated our false positive and false negative rates as a function of the percent increase in RLS and sample size n (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table S3, related to Figure 2). These results suggest that the estimated total number of additional viable deletions that extend RLS >50% relative to wild-type is likely <1. For a 40% increase in RLS, we estimate ~10 additional viable deletions, and for a 30% increase, ~58 additional viable deletions (Supplemental Table S3, related to Figure 2). In considering false negative rates, it is worth stating explicitly that there is a class of S. cerevisiae genes whose effects cannot be reflected in this work: essential genes. Further, previous work (Curran and Ruvkun, 2007) has suggested that essential genes may be more likely than non-essential genes to have a strong effect on lifespan, implying that the number of essential longevity genes remaining to be discovered could exceed a rough approximation based on extrapolation from non-essential genes.

Figure 2.

A. Estimated false positive rate for given percent increase in RLS and number of mother cells n. x-axis indicates % increase in RLS relative to wild type control, y-axis indicates sample size n, and z-axis and point color indicate estimated false positive proportion. B. Estimated false negative rate at a threshold of 30% increased RLS, for given actual percent increased RLS and number of mother cells n. x-axis indicates actual % increase expected for the genotype, z-axis indicates the estimated false negative proportion using a 30% screening cutoff, and point color indicates sample size n (black, n=5, blue, n=10, red, n=40).

Lifespan-extending deletions are clustered in known and highly conserved functional pathways

A biologically meaningful list of lifespan-extending genes is unlikely to be a random assortment, and the genes identified in our screen are not; many of these genes cluster into known functional groups. All of these groups are conserved from yeast to humans. Genes whose molecular function category is overrepresented among our long-lived deletions are summarized by category (Table 1), and individual categories are described further. A network showing all long-lived deletions as nodes, and published physical protein-protein interactions as edges, shows that many of the genes not only cooperate in related functional processes, but are physically bound in protein complexes such as the cytosolic ribosome, mitochondrial ribosome, and SAGA complex (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Genes that comprise overrepresented functional categories among longlived single gene deletions.

| Cytosolic Ribosome | Mitochondrial Translation | Mannosyltransferase | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene | mean RLS | % inc. | gene | mean RLS | % inc. | gene | mean RLS | % inc. |

| RPL12A | 30.11 | 17.7 | CBS1 | 31.60 | 36.8 | ALG12 | 31.75 | 16.6 |

| RPL12B | 33.80 | 21.6 | IMG1 | 33.11 | 22.5 | ALG6 | 30.36 | 15.3 |

| RPL13A | 34.68 | 36.9 | IMG2 | 29.57 | 28.0 | EOS1 | 35.03 | 23.9 |

| RPL13B | 34.70 | 36.6 | MRPL33 | 28.04 | 16.3 | MNN1 | 30.54 | 14.7 |

| RPL16B | 35.09 | 22.7 | MRPL40 | 33.27 | 20.7 | MNN2 | 30.47 | 15.5 |

| RPL19A | 34.26 | 29.6 | MRPL49 | 34.69 | 25.2 | PMT1 | 35.08 | 38.1 |

| RPL19B | 32.36 | 15.7 | MSK1 | 28.49 | 11.6 | PMT3 | 31.88 | 26.8 |

| RPL1B | 31.13 | 24.1 | MSW1 | 32.82 | 26.0 | PMT5 | 29.07 | 20.6 |

| RPL20A | 35.80 | 44.4 | SOV1 | 31.29 | 16.8 | YUR1 | 31.18 | 19.2 |

| RPL20B | 36.40 | 35.0 | SUV3 | 33.82 | 21.8 | |||

| RPL21B | 36.93 | 49.5 | YDR115W | 30.13 | 11.7 | |||

| RPL22A | 36.59 | 38.4 | ||||||

| RPL23A | 34.02 | 31.9 | TCA Cycle | SAGA | ||||

| RPL26A | 31.39 | 21.6 | gene | mean RLS | % inc. | gene | mean RLS | % inc. |

| RPL29 | 32.08 | 31.9 | EMI5 | 31.66 | 28.3 | CHD1 | 31.06 | 13.5 |

| RPL2B | 34.30 | 38.3 | IDH1 | 32.68 | 17.3 | SGF11 | 36.64 | 25.8 |

| RPL31A | 34.85 | 30.0 | IDH2 | 30.88 | 15.0 | SGF73 | 40.81 | 55.1 |

| RPL34A | 34.20 | 27.4 | IDP1 | 28.37 | 9.0 | SPT8 | 31.50 | 9.1 |

| RPL34B | 37.80 | 48.0 | LPD1 | 31.55 | 36.8 | UBP8 | 36.02 | 34.4 |

| RPL35A | 24.80 | 41.2 | SDH1 | 32.75 | 24.9 | |||

| RPL37B | 29.99 | 26.6 | SDH2 | 32.09 | 21.3 | |||

| RPL43B | 32.51 | 35.0 | ||||||

| RPL6A | 35.50 | 43.1 | ||||||

| RPL6B | 31.51 | 16.6 | ||||||

| RPL7A | 32.10 | 19.0 | ||||||

| RPL9A | 31.43 | 27.1 | ||||||

| RPP1A | 37.38 | 30.7 | ||||||

| RPP1B | 32.91 | 23.4 | ||||||

| RPP2A | 26.39 | 14.9 | ||||||

| RPP2B | 34.85 | 50.2 | ||||||

| RPS12 | 32.62 | 38.3 | ||||||

| RPS6A | 30.05 | 10.2 | ||||||

Lifespan is altered by proteins involved in both cytosolic and mitochondrial translation, the SAGA complex, protein mannosylation, the TCA cycle, and proteasomal activity

The largest functional category of long-lived deletions is the cytosolic ribosome. These 32 genes include 26 paralogs encoding 20 protein components of the large ribosomal subunit, 4 paralogs encoding 2 proteins in the ribosomal stalk, and 2 paralogs encoding 2 proteins in the small ribosomal subunit. This function is conserved; several components of the large subunit of the cytosolic ribosome have also been shown to affect lifespan in C. elegans (Chen et al., 2007; Curran and Ruvkun, 2007; Hansen et al., 2007).

Ribosomal gene deletions were one of the first categories noted to be long-lived during the progress of this project. Four previous publications, three from our group (Kaeberlein et al., 2005; Steffen et al., 2008; Steffen et al., 2012) and one other (Chiocchetti et al., 2007) have investigated the mechanism by which deletion of large subunit genes extends RLS, leading to the identification of the nutrient-responsive transcription factor Gcn4 as an important downstream mediator of longevity (Steffen et al., 2008).

Overall Ribosome and Cytosolic Ribosome are detected independently as overrepresented categories, due to the fact that alongside the components of the cytosolic ribosome, we identified genes encoding 6 components of the large subunit of mitochondrial ribosome; IMG1, IMG2, MRPL33, MRPL40, MRPL49, and YDR115W. We also saw increased RLS upon deletion of the genes encoding 2 mitochondrial tRNA synthetases, MSK1 and MSW1, and three mitochondrial translation control (MTC) genes, SOV1, SUV3, and CBS1, which themselves affect levels of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins. Deletion of these three MTC genes has been shown previously to extend yeast RLS (Caballero et al., 2011). The bias toward the large subunit seen in the RLS-extending cytosolic ribosome deletions is repeated in the mitochondrial ribosome. It will be interesting to learn how much the mechanisms of RLS extension by deletion of cytosolic ribosomal components and mitochondrial ribosomal components have in common.

The yeast SAGA and SLIK chromatin remodeling complexes and the orthologous human complexes STAGA and SALSA are histone-modifying complexes which contain at least two enzymatic activities: a protein acetyltransferase (in yeast, Gcn5), and a deubiquitinase (in yeast, Ubp8) (Samara et al., 2010). The Ubp8 deubiquitinase acts as part of a deubiquitinating module, or DUBm, alongside Sgf73, Sgf11, and Sus1. Deletions of genes encoding three of the four DUBm components, Ubp8, Sgf73, and Sgf11, increase yeast RLS significantly, and sgf73Δ has one of the largest RLS increases seen in our screen. These genes were also identified early in our screen, and a parallel project has now looked in more detail at the mechanisms by which disruption of the SAGA/SLIK DUBm may increase yeast RLS (McCormick et al., 2014).

Protein O-mannosylation is an essential modification that occurs at the endoplasmic reticulum and is conserved from yeast to humans (Hutzler et al., 2007). In yeast, three mannosyltransferase subfamilies, PMT1 (consisting of Pmt1 and Pmt5), PMT2 (Pmt2 and its paralog Pmt3), and PMT4, are thought to mannosylate distinct protein targets (Gentzsch and Tanner, 1997). In our screen, PMT1, PMT3 and PMT5 all significantly extended yeast RLS. Closer inspection of the remaining individual PMT gene deletions revealed additional interesting results: pmt2Δ just missed the cutoff for inclusion, exhibiting a 26.3% increase in RLS (p<0.038) in MATa, and a 15.6% increase (p<0.054) in MATα. pmt6Δ and pmt7Δ each extended RLS in one mating type when tested (22.6% and 31.3%, respectively), but not in the other mating type, leaving open the possibility that the non-extended mating type in each case may harbor a second mutation which masks the RLS phenotype of the deletion. We also identified the two yeast mannosyltransferases involved in O-linked glycosylation, MNN1 and MNN2, the N-linked mannosyltransferases YUR1, ALG6, and ALG12, and EOS1, which has been implicated in protein N-glycosylation.

Recently, Labunskyy et al. reported that yeast lacking ALG12 and BST1, which controls ER-to-Golgi transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (Tanaka et al., 2004), were long-lived because they activate the unfolded protein response, which promotes multiple forms of stress resistance (Labunskyy et al., 2014). It remains to be determined whether other long-lived deletions of mannosyltransferase-related genes enhance RLS by this mechanism.

We identified 7 genes encoding proteins central to the tricarboxylic acid pathway: isocitrate dehydrogenase subunits IDP1, IDH1, and IDH2, lipoamide dehydrogenase LPD1, and succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDH1, SDH2, and EMI5/SDH5. All of these genes are involved in a very short section of the TCA cycle: the conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate (IDP1, IDH1, IDH2), on to succinyl-CoA (LPD1), and from there to succinate and then fumarate (SDH1, SDH2, EMI5). It is interesting to note that this pathway converges on many events linked to longevity, including production of amino acids that regulate TOR activity, control of metabolite levels including NAD(+), and use of different substrates for ATP production (Imai et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2007).

Although not overrepresented by automated gene ontology analysis, one of the longest-lived single deletions identified here is that of UBR2, a ubiquitin ligase that regulates the turnover of the transcription factor Rpn4, which positively regulates transcription of components of the yeast proteasome. As the extended RLS of ubr2Δ depends completely on Rpn4, we concluded that proteasomal activity is central to this phenotype (Kruegel et al., 2011), and we have recently dissected the RLS effects of UBR2 and RPN4 in additional detail (Yao et al., 2015).

RLS-extending single gene deletions in yeast overlap at high significance with known lifespan-extending hypomorphs in C. elegans

We examined whether these data would provide further evidence of evolutionary conservation of longevity pathways. To test this, we asked whether our RLS-extending deletions overlapped significantly with genes whose knockdown or deletion was reported to extend the lifespan of the distantly related nematode C. elegans. We compiled a list of 424 genes whose deletion, hypomorphic or null allele mutation, or RNAi knockdown had been reported to extend C. elegans lifespan, taking as our starting point previous work where a portion of the yeast genome was similarly examined (Smith et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2008) (Supplemental Table S4, related to Table 2). We then used paralog-ortholog groups generated by InParanoid (Ostlund et al., 2010) to find genes whose lifespan-extending phenotype was shared between S. cerevisiae and C. elegans, and calculated the probability of an overlap of the observed magnitude. Long-lived yeast deletions whose hypomorphic lifespan extension has also been reported in C. elegans are shown in Table 2. The probability of this overlap absent functional conservation of lifespan phenotypes (i.e. at random) is p<4.4E-11. Because of the large number of ribosomal proteins present in both species’ lifespan-altering orthologs, we asked whether they alone were responsible for the significance of the overlap we observed, and found that the remaining list still exhibited a significant overlap (p<1.0E-7) with ribosomal proteins omitted.

Table 2.

Lifespan phenotypes of yeast deletions are significantly conserved. Listed are genes whose deletion in S. cerevisiae was shown to increase RLS in this screen, and whose C. elegans orthologs have been published to have increased lifespan upon deletion, hypomorphic mutation, or RNAi knockdown. poverlap<4E-11; if all ribosomal genes are excluded poverlap<1E-7.

| Worm Orthologs | Yeast Orthologs | Worm Orthologs | Yeast Orthologs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ant-1.1 | AAC3 | AAC1 | pps-1 | MET3 | |||

| blmp-1 | MIG1 | pptr-1 | RTS1 | ||||

| cyc-2.1 | CYC1 | rab-5 | VPS21 | ||||

| cyp-13A4 | DIT2 | rpl-19 | RPL19B | ||||

| dod-18 | YOR111W | rpl-34 | RPL34A | RPL34B | |||

| his-71 | HHT1 | rpl-6 | RPL6B | ||||

| idh-1 | IDP1 | rpl-9 | RPL9A | ||||

| ifg-1 | TIF4632 | TIF4631 | rps-11 | RPS11A | |||

| inf-1 | TIF2 | TIF1 | rps-6 | RPS6A | |||

| isw-1 | ISW2 | rps-8 | RPS8A | ||||

| let-363 | TOR1 | sams-1 | SAM1 | ||||

| lgg-1 | ATG8 | sodh-2 | ADH2 | ||||

| nac-2 | nac-3 | PHO87 | spg-7 | AFG3 | |||

| par-5 | BMH2 | spl-1 | DPL1 | ||||

| spt-4 | SPT4 | ||||||

We note that the genes affecting both yeast and C. elegans lifespan contain a similar proportion of genes from our functionally overrepresented pathways as the screen as a whole. Specifically, 0.255 of the overall screen results fall into the functionally overrepresented groups such as the ribosome, TCA cycle, SAGA, etc., while 0.276 of the conserved genes do so, a higher proportion by gene. Nevertheless, not all 5 functionally overrepresented pathways we describe here in yeast are represented among the conserved genes; only 2 (ribosome and TCA cycle) are. We propose at least two possible factors that may contribute to the absence of the other pathways. First, although we here quantify the false negative rate of our screen with high precision, our list of C. elegans genes is generated by consideration of aggregate data from multiple studies, most of which are not whole-genome studies, whose aggregate false negative rate cannot be easily estimated. We suspect that some absences from our list of conserved genes may be because the phenotype has not been observed in C. elegans although it may exist. Further, interspecies ortholog prediction is an imperfect science. In the example of the SAGA group, although both the individual genes and the overall protein complexes are conserved at the sequence and functional level between yeast, mice, and humans, we were not able to identify putative C. elegans orthologs for any of the RLS-extending SAGA deletions. We do not know whether this is due to sequence divergence, complete loss of this functionality from C. elegans, or other reasons, but it may offer an additional explanation for the fact that not every pathway we have uncovered in yeast is represented in the smaller subset of identified conserved genes.

Taken in context, the highly significant overlap between the final results of our screen of viable yeast deletions and published C. elegans genes suggests a high degree of general conservation in lifespan genotypephenotype relationships between very distantly related species. This leaves open the possibility that these genes may be enriched for orthologs that can alter lifespan and aging in other organisms, such as humans.

Nuclear tRNA accumulation is associated with increased RLS

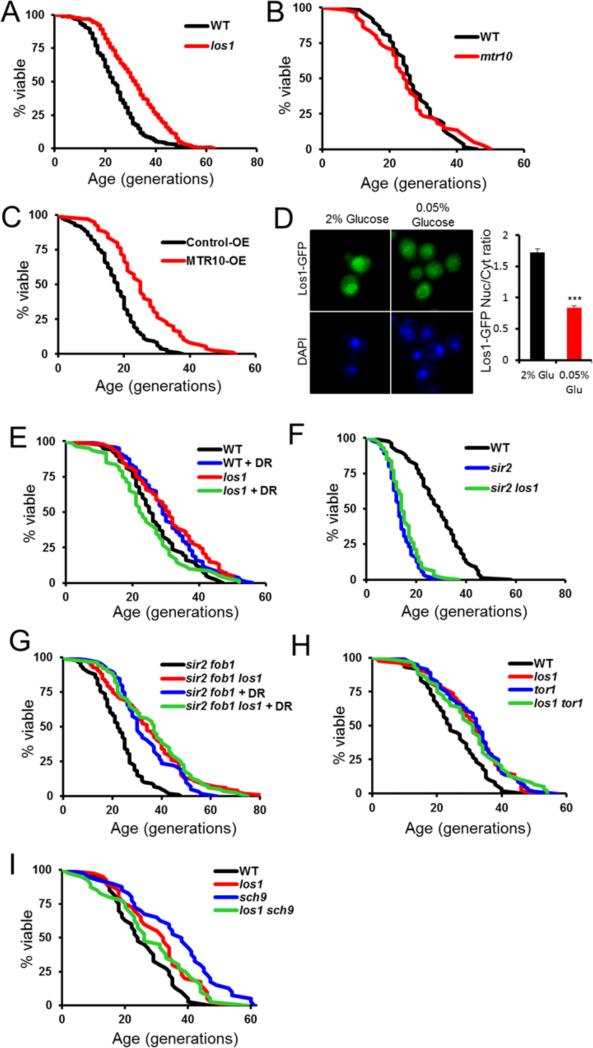

Among the long-lived deletions identified in our screen, we chose to further examine los1Δ, as it had a dramatically enhanced RLS (p<0.001, Figure 3A), and Los1 has a function not previously linked to aging: subcellular localization of tRNA.

Figure 3.

Regulators of nuclear tRNA import and export influence lifespan, and DR and los1Δ act in the same pathway. A. Deletion of the nuclear tRNA exporter gene LOS1 extends RLS. B. Deletion of tRNA importer gene MTR10 does not reduce RLS. C. Additional copy of the nuclear tRNA importer MTR10, which functions antagonistically to LOS1, extends RLS. D. Blinded scoring of fluorescence microscopy reveals that DR (0.05% glucose) reduces nuclear Los1-GFP, ***p<0.001. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). E through I. RLS analysis indicates that deletion of LOS1 acts similarly to DR. Deletion of LOS1 fails to extend RLS of sir2Δ cells, but robustly extends RLS of sir2Δfob1Δ cells. Deletion of LOS1 does not increase RLS additively with DR or with genetic mimics of DR (tor1Δ and sch9Δ). RLS and microscopy statistics are provided in Supplemental Table S5.

Since Los1 is known to function as a nuclear tRNA exporter, and deletion of LOS1 leads to increased levels of nuclear tRNA (Sarkar and Hopper, 1998), we tested whether altered import of tRNA into the nucleus could also modulate RLS. Mtr10 is a nuclear import receptor required for retrograde transport of tRNAs from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (Shaheen and Hopper, 2005). Deletion of MTR10 had no effect on RLS (p=0.9, Figure 3B), but overexpression of MTR10 under its native promoter from a low copy plasmid significantly increased RLS relative to a control plasmid (p<0.001, Figure 3C). Taken together, these data indicate that either blocking nuclear export or enhancing nuclear import of tRNA is sufficient to extend yeast RLS.

DR and Los1 similarly modulate RLS

Given prior data that Los1 is excluded from the nucleus upon complete glucose starvation (Quan et al., 2007), we examined whether Los1 was responsive to DR, by reducing the glucose concentration of the medium from 2% to 0.05%. Relative to control conditions, DR significantly reduced the amount of Los1-GFP in the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm (p<0.001, Figure 3D). DR also failed to further increase the RLS of long-lived cells lacking LOS1 (Figure 3E).

Prior studies have shown that DR fails to increase the RLS of sir2Δ single mutant cells lacking the Sir2 histone deacetylase, but robustly increases the RLS of sir2Δ fob1Δ double mutant cells (Delaney et al., 2011b; Kaeberlein et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2000). Similarly, deletion of LOS1 did not increase the RLS of sir2Δ cells, but significantly increased the RLS of sir2Δ fob1Δ cells (p<0.001, Figure 3F, G). Again, los1Δ did not further extend RLS when combined with DR in the sir2Δ fob1Δ background (Figure 3G).

As an additional test of whether Los1 acts downstream of DR to modulate lifespan, we combined deletion of LOS1 with two well-characterized genetic mimetics of DR, deletion of TOR1 or SCH9. As with DR by glucose restriction, deletion of TOR1 or SCH9 also failed to further increase RLS in los1Δ mother cells (Figure 3H, I). Interestingly, sch9Δ los1Δ cells are slightly shorter lived than sch9Δ single mutant cells, and los1Δ cells are shorter lived under DR conditions relative to control conditions, similar to the previously observed effect of combining DR with sch9Δ (Kaeberlein et al., 2005). These data indicate that genetically altering tRNA transport to favor accumulation of nuclear tRNA is sufficient to extend RLS, and support a model in which nuclear sequestration of tRNA via regulation of Los1 localization is one mechanism by which DR increases RLS.

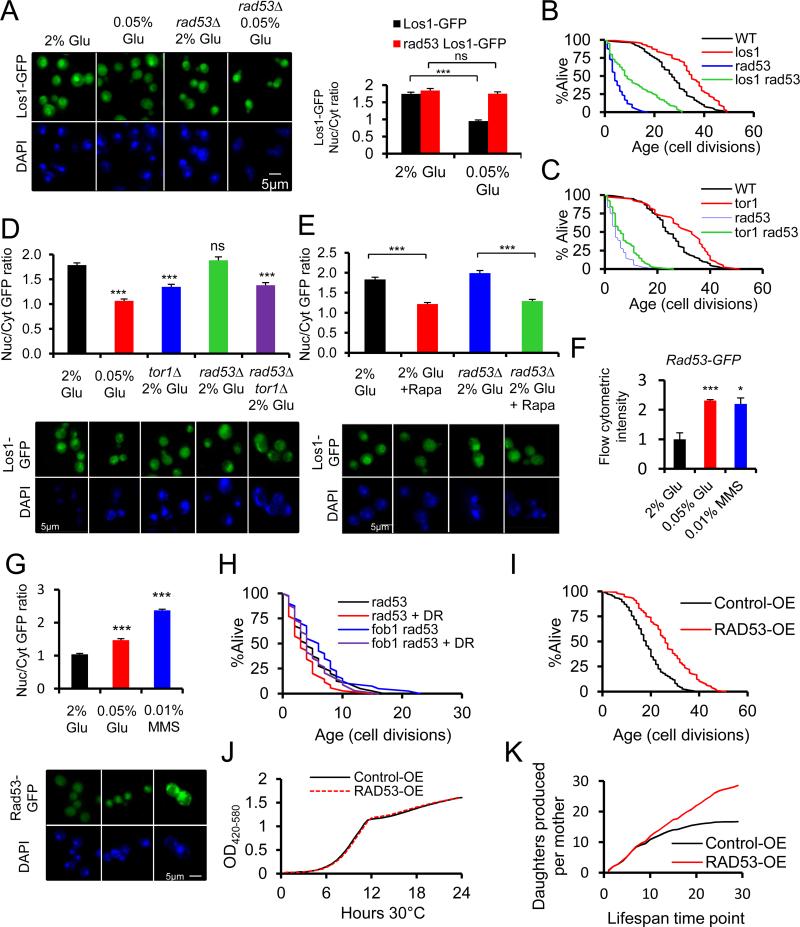

Los1 is regulated by both Rad53 and mTOR downstream of DR

A previous report showed that Rad53 activation by DNA damage causes Los1 export to the cytoplasm, resulting in nuclear sequestration of tRNA (Ghavidel et al., 2007). Rad53 has been previously implicated in aging (Delaney et al., 2013; Schroeder et al., 2013; Weinberger et al., 2010) but not linked to the response to DR. Redistribution of Los1 to the cytoplasm in response to DR was prevented in cells lacking RAD53 (p=0.1, Figure 4A, Supplemental Table S5, related to Figure 4). Despite the fact that rad53Δ cells are extremely short-lived, and in some backgrounds inviable (Zhao et al., 2001), deletion of LOS1 was still able to significantly extend RLS in this background (p<0.001), consistent with the model that Rad53 acts between DR and Los1 to modulate RLS (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Rad53 acts between DR and Los1, but not Tor1, is enhanced by DR, and modulates lifespan. A. Fluorescence microscopy indicates that Rad53 is required for nuclear exclusion of Los1-GFP in response to DR. B. RLS analysis demonstrates that Rad53 is not required for RLS extension by deletion of either LOS1 or C. TOR1. D. Fluorescence microscopy indicates that Rad53 is not required for nuclear exclusion of Los1-GFP in response to deletion of TOR1 or E. by addition of 1nM rapamycin. F. Levels of Rad53-GFP in the cell, normalized to 2% glucose growth conditions, as assayed by flow cytometry. G.GFP-tagged Rad53 is enriched in the nucleus by DR. H. RLS analysis demonstrates that Rad53 is required for RLS extension from DR. I. Additional copy of RAD53 extends RLS. J. Representative growth curves of RAD53 overexpression. K. Mother cell divisions of Rad53-OE and wild type on agar as a function of chronological time. RLS and microscopy statistics are provided in Supplemental Table S5. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Since reduced mTOR signaling is believed to mediate RLS extension from DR (Kaeberlein et al., 2005), we attempted to place mTOR genetically within the longevity pathway containing DR, Los1, and Rad53. Rad53 is not required for deletion of TOR1 to extend RLS (p=0.005, Figure 4C), suggesting that mTOR acts at least partially independently of Rad53. Both los1Δ and tor1Δ alter the mortality kinetics of rad53Δ cells, possibly by reducing a stochastic lifespan-limiting event. Interestingly, Los1-GFP is also enriched in the cytoplasm of tor1Δ cells under nutrient rich conditions, albeit to a lesser extent than in wild type cells subjected to DR (p<0.001, Figure 4D). Unlike DR, however, cytoplasmic localization of Los1-GFP in tor1Δ cells does not require Rad53 (p<0.001). Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR complex I that extends lifespan in yeast, worms, fruit flies, and mice (Ramos and Kaeberlein, 2012), also causes Los1-GFP to become enriched in the cytoplasm in a Rad53-independent manner (p<0.001, Figure 4E).

To further explore the role of Rad53 in the DR response, we examined the effect of DR on Rad53 abundance and localization using a strain expressing Rad53-GFP fusion protein under the control of the RAD53 promoter. DR significantly increased Rad53 nuclear and overall abundance (p<0.001), comparable to treatment with MMS, a known inducer of Rad53 (p<0.001, Figure 4F, G). Deletion of RAD53 prevented RLS extension from DR in both wild type and fob1Δ cells (Fig 4H). Importantly, overexpression of RAD53 was sufficient to extend RLS in an otherwise wild type background (p<0.001, Figure 4I), comparable to the effect of MTR10 overexpression or LOS1 deletion (Figure 2A, C). This RLS extension from RAD53 overexpression was not associated with a significant change in growth rate either in liquid culture or on agar plates during the lifespan experiment (Figure 4J,K), indicating that overexpression of RAD53 is not sufficient to induce the DNA damage cell-cycle checkpoint.

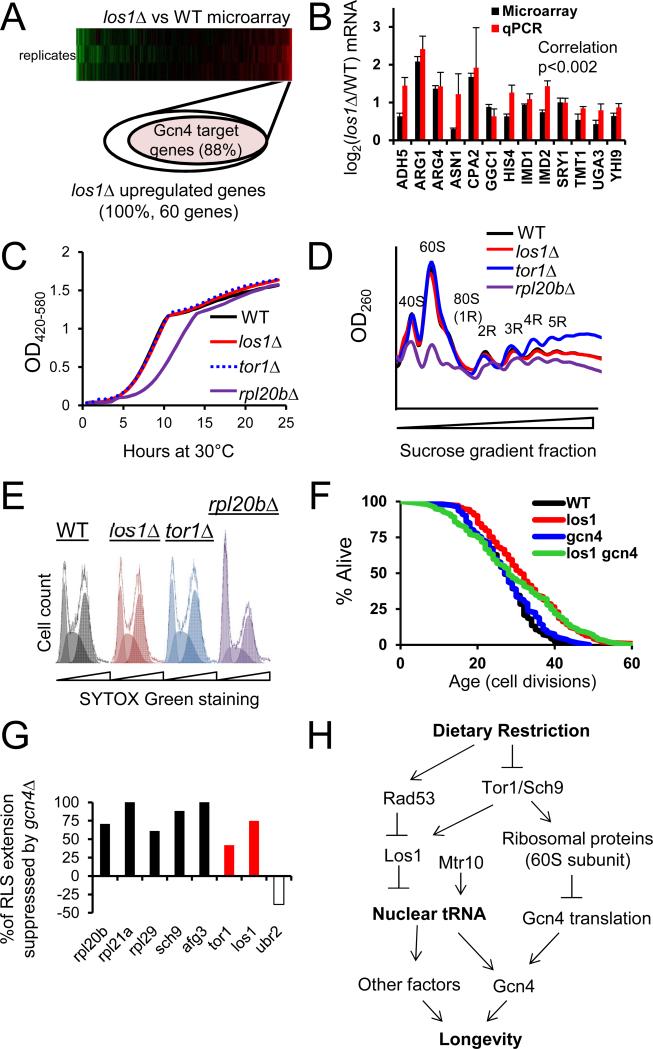

Deletion of LOS1 induces Gcn4 targets without reducing mRNA translation

To further characterize the mechanism by which Los1 regulates RLS, we compared gene expression profiles of wild type and los1Δ cells under non-restricted conditions. 60 genes were identified with significantly increased expression in los1Δ cells, and 31 with significantly reduced expression (Supplemental Table S6, related to Figure 5). Gene ontology analysis indicated that a majority of the mRNAs upregulated in los1Δ cells encoded proteins involved in amino acid biosynthesis and nitrogen metabolism (Supplemental Table S6, related to Figure 5). Of 60 genes upregulated in los1Δ cells, 88% are annotated as targets of the Gcn4 transcription factor on Yeastract (Teixeira et al., 2006) (Figure 5A, Supplemental Table S6, related to Figure 5, p<0.0001 enriched for Gcn4 targets compared to downregulated genes). Upregulation of GO term enriched genes was confirmed by qPCR (Figure 5B, C, Supplemental Table S8, related to Figure 5). This reinforces prior evidence that Gcn4 is activated under conditions where tRNA is sequestered in the nucleus (Ghavidel et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2000), and is consistent with the model that Gcn4 acts downstream of DR and mTOR to promote longevity (Steffen et al., 2008).

Figure 5.

Deletion of LOS1 activates GCN4 without reducing global mRNA translation, and Gcn4 is necessary for RLS extension by los1Δ. A. Relative proportions of Gcn4 regulated genes within the subset of genes found via microarray to be upregulated in los1Δ yeast. B. RT-qPCR verification of a subset Gcn4 target genes found to be upregulated by microarray analysis of los1Δ cells, focused on enriched GO term related genes. C. Representative growth curves, D. polysome profiles, and E. cell cycle profiles of los1Δ, tor1Δ, and WT yeast indicate that neither los1Δ nor tor1Δ cells have a detectable defect in mRNA translation. For comparison, a translation-deficient rpl20Δ mutant is shown in each case. R values in panel E correspond to the number of ribosomes bound to a particular mRNA. F. Deletion of GCN4 partially blocks RLS extension from deletion of LOS1. G. Deletion of GCN4 largely prevents RLS extension in genetic models of DR, but not the DR independent Ubr2 pathway. Percent suppression of RLS is calculated by comparing the percent mean RLS extension of the long lived mutant in wild type and gcn4Δ backgrounds. RLS statistics are provided in Supplemental Table S5. H. Diagram summarizing the comprehensive model for DR supported by the data from this study. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Given that los1Δ mutants have reduced cytoplasmic tRNA and increased expression of Gcn4 target genes, we hypothesized that loss of LOS1 may extend RLS by decreasing 60S mRNA translation, similar to RPL20B (Steffen et al., 2008). Unexpectedly, we were unable to detect any change in global mRNA translation in los1Δ cells, by growth rate in rich media, polysome analysis, or cell cycle progression (Figure 5C-E). A similar lack of suppression of mRNA translation was also observed in long-lived tor1Δ cells, while the rpl20bΔ cells had a significant defect. Similar to tor1Δ, Gcn4 partially but not completely prevented RLS extension from deletion of LOS1 (Figure 5F). The magnitude of RLS suppression from GCN4 deletion in los1Δ cells is comparable to the effects in tor1Δ cells or cells subjected to DR and cells lacking full 60S translation capacity, such as sch9Δ, afg3Δ (Delaney et al., 2012), and rplΔs (Figure 5G). Lifespan abrogation is not seen in a DR-independent pathway mutant ubr2Δ (Kruegel et al., 2011). These data suggest that Gcn4 is activated in los1Δ cells through a mechanism distinct from reduced global mRNA translation, and this Gcn4 activation contributes to increased RLS (Figure 5H).

DISCUSSION

The work summarized here represents one of the most comprehensive ORFeome-wide screens of any model organism for increased lifespan, comprising data from manual dissection of over 2.2 million individual yeast daughter cells. The scale of this screen gives a unique snapshot of the pathways involved in the regulation of lifespan in a single eukaryotic model organism, and has identified multiple significantly overrepresented functional processes. This includes a role for Los1-mediated tRNA transport downstream of dietary restriction, which we have dissected further. Many of the longevity genes identified here are known to act in longevity pathways conserved in multiple species (e.g., components of the cytosolic ribosome), or have greatly extended a functional category which had already shown some genes involved in aging (mitochondrial translation). Others, like the LOS1 pathway, are largely unstudied (e.g. mannosyltransferase, TCA cycle metabolism). Two gene ortholog groups that modulate the lifespan of yeast and other organisms, mTOR and sirtuins, have already pointed to drugs that extend the lifespan of mice (Harrison et al., 2009; Kaeberlein et al., 2005; Li et al., 2014; Li and Miller, 2014; Mitchell et al., 2014), and each of the pathways described here should be considered with this potential in mind.

While many genes identified here cluster into functionally related groups, some genes are alone or unknown in their molecular function, which may yield further unexpected links. For example, the oligosaccharyltransferase complex directly binds to the yeast ribosome at a location near the translocon-binding site, which is on the 60s ribosomal subunit (Harada et al., 2009). This may link the lifespan extension in the PMT1/PMT3/PMT5 mannosyltransferase complex deletions and that of the 60s subunit-biased ribosomal protein gene deletions.

The detailed analysis here defining a previously unsuspected role for regulation of nuclear tRNA export in modulating longevity provides further insights into linking longevity pathways that may initially appear disparate. Our data demonstrate that Rad53 and mTOR are both regulated by DR and likely act through parallel mechanisms to influence Los1 localization (Figure 5). This fits with prior data suggesting that Rad53 regulates Los1 in response to DNA damage (Ghavidel et al., 2007), similar to Ntg1 translocation during mtDNA stress (Schroeder and Shadel, 2014), as well as evidence that the nutrient responsive hexokinase Hxk2 and cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway are important for appropriate regulation of the Rad53 checkpoint following DNA damage (Searle et al., 2011). Both Hxk2 and PKA have been previously shown to act within the DR pathway in yeast, further supporting this link (Kaeberlein et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2000). In this regard, it is worth noting that neither DR nor overexpression of RAD53 is sufficient to induce the DNA damage checkpoint in the absence of DNA damage (Supplemental Figure S4, related to Figure 5). Thus, the data presented here provide intriguing connections between DNA maintenance, nutrient response pathways, tRNA transport, and aging. While tRNA synthetases and modifying enzymes have been reported to modulate aging in C. elegans (Lee et al., 2003; Yanos et al., 2012), it remains unclear whether the mechanisms are related to those described here.

Some divergence in phenotype was noted for tor1Δ, sch9Δ, and los1Δ. Deletion of LOS1 did not alter translation, nor does tor1Δ, but deletion of SCH9 reduces translation and slows the cell cycle. RLS extension in a los1Δ background was antagonistic in sch9Δ, but not in tor1Δ. It is currently unclear whether translation rates are the cause for these differences, or if signal transduction downstream of DR causes post-translational changes of Los1 and/or Tor1. Glucose deprivation may selectively act on Los1 localization via PKA inactivation rather than Snf1/AMPK inactivation (Pierce et al., 2014), which may partially explain the phenotypic differences between these partial DR mimetic mutants.

Based on data presented here and previously, we suggest a model whereby modest reductions in signaling through mTOR can promote longevity by engaging Gcn4 via Los1-dependent nuclear sequestration of tRNA. The branches of this pathway (Rad53, mTOR, ribosomal proteins) ultimately converge on shared Gcn4 targets, explaining the non-additive effects on lifespan when two long-lived mutants within the pathway are combined. Notably, there is accumulating evidence for a role of the GCN4 ortholog, ATF4, in mammalian longevity as ATF4 is upregulated in the liver of Snell dwarf and PAPP-A knockout mice, acarbose and rapamycin treated mice, and calorically restricted and methionine restricted mice, all of which are long-lived (Li et al., 2014; Li and Miller, 2014).

Finally, it is remarkable that so many yeast gene knockouts extend lifespan. This parallels findings from worm genome-wide screens, and raises the question of why it is so easy to extend lifespan genetically. The answer likely lies in evolutionary theories of aging, which posit that organisms are optimized for fitness and not long lifespan. Fitness in yeast likely means a rapid mitotic growth rate when nutrients are available and retention of meiotic capacity, but not the ability to generate 30 daughters instead of 25 when mother cells are swamped by offspring of previous daughters. Since late life vigor lacks selection, there may be many ways to extend lifespan in mammals as well.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Additional information can be found in Extended Experimental Procedures

Strains and media

All yeast strains were derived from the parent strains of the haploid yeast ORF deletion collections (Winzeler et al., 1999), BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0) and BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0). A list of all strains not contained in either haploid ORF deletion collection is included in Supplemental Table S7, related to Figure 3. Cells were grown on standard YPD containing 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone and 2% glucose, at 30°C, unless otherwise stated.

Replicative Lifespan

Yeast RLS assays were performed as previously described (Kaeberlein et al., 2004; Steffen et al., 2009). In short, virgin daughter cells were isolated from each strain and then allowed to grow into mother cells while their corresponding daughters were microdissected and counted, until the mother cell could no longer divide. Statistical significance was determined by calculating p-values using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test (Wilcoxon, 1946).

Gene Ontology and Network Analysis

Gene ontology and network analysis was performed using GeneMANIA (Warde-Farley et al., 2010), using all available GeneMANIA published physical protein-protein interaction datasets at the time of the analysis.

Fluorescence microscopy

GFP labeled cells were grown to log phase under selection in SC-HIS media, and imaged in fresh liquid media on a Teflon printed slide. Pictures were taken on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M, blinded, and analyzed on Zeiss Axiovision microscopy software.

Flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis, all samples were prepared following a protocol previously described (Delaney et al., 2011a).

Growth curves

All yeast growth rates were analyzed in the OD420-580 range in the Bioscreen C automated microbiology growth curve analysis system (Growth Curves USA, Piscataway, NJ, USA) as previously described using the Yeast Outgrowth Data Analyzer (YODA) software (Olsen et al., 2010).

Polysome profiles

All polysome analysis was carried out as described previously (MacKay et al., 2004; Steffen et al., 2008). Briefly, log phase yeast cultures were chilled with crushed frozen YPD plus 100 μg/ml cycloheximide. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 10 ml lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 40 mM KCl, 7.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mg/ml heparin, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide) and resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer. Cells were then lysed by vortexing with glass beads. Triton X-100 and sodium deoxycholate were added to a final concentration of 1% and samples were left on ice for 5 minutes before the supernatant was clarified by centrifugation. All reagents were ice-cold and all steps were done in a 4°C cold room. For separation on gradients, 1 ml containing 20 A260 units of lysate were loaded onto 11-ml linear 7%–47% sucrose gradients in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.8 M KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mg/ml heparin, and 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, and sedimented at 39,000 rpm at 4°C in an SW40 Ti swinging bucket rotor (Beckman) for 2 hr. Gradients were collected from the top and profiles were monitored at 254 nm.

Microarrays

Log phase (exactly 0.5 OD600) yeast were harvested and RNA extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA). Six wild type cultures and three independently created los1Δ isolates were used, with paired cultures on three independent days. Affymetrix GeneChip Yeast Genome 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Hybridized arrays were scanned with an Affymetrix GeneChip 3000 scanner. Image generation and feature extraction were performed using Affymetrix Gene Chip Command Console software. Raw data was processed and analyzed with Bioconductor. False discovery rates were used at a q value cutoff of 0.05. The data were deposited in the GEO public database, accession number GSE37241.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

-4,698 deletions tested yields the most comprehensive yeast dataset on aging

-Longevity clusters center on known, conserved biological processes

-Enrichment of lifespan-extending C. elegans orthologs suggests conservation

-Genome-wide information uncovered aging pathways such as tRNA transport

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of the Kennedy and Kaeberlein labs for technical assistance and helpful discussion. This study was supported by NIH Grants R01AG043080 and R01AG025549 to B.K.K and R01AG039390 to M.K. Additional support for flow cytometry, lifespan, and microarray analysis was provided by the University of Washington Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging (NIH P30AG013280). M.M. was supported by NIH training grant T32AG000266. J.R.D, G.L.S., E.D.S, and K.K.S were supported by NIH Training Grant T32AG000057. J.S. and B.M.W. were supported by NIH Training Grant T32ES007032. B.K.K. is an Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar in Aging. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

M.M., J.R.D., M.K., and B.K.K. conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript. M.M., J.R.D., A.S., S.S., A.C., and U.A. generated the yeast strains and contributed to execution and data analysis of all experiments except mouse experiments. J.R.D. and all authors excluding S.J., R.B., T.B., B.O., D.P., R.B.B., X.L., Y.S., Z.Z., and B.K.K. performed the lifespan measurements. D.P. conducted flow cytometry experiments. B.O. assisted in data analysis. R.B. and T.B. executed the microarray analysis. M.K. and B.K.K. provided reagents and support for the studies. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Caballero A, Ugidos A, Liu B, Oling D, Kvint K, Hao X, Mignat C, Nachin L, Molin M, Nystrom T. Absence of mitochondrial translation control proteins extends life span by activating sirtuin-dependent silencing. Molecular cell. 2011;42:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Pan KZ, Palter JE, Kapahi P. Longevity determined by developmental arrest genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiocchetti A, Zhou J, Zhu H, Karl T, Haubenreisser O, Rinnerthaler M, Heeren G, Oender K, Bauer J, Hintner H, et al. Ribosomal proteins Rpl10 and Rps6 are potent regulators of yeast replicative life span. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SP, Ruvkun G. Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JR, Ahmed U, Chou A, Sim S, Carr D, Murakami CJ, Schleit J, Sutphin GL, An EH, Castanza A, et al. Stress profiling of longevity mutants identifies Afg3 as a mitochondrial determinant of cytoplasmic mRNA translation and aging. Aging Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1111/acel.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JR, Chou A, Olsen B, Carr D, Murakami C, Ahmed U, Sim S, An EH, Castanza AS, Fletcher M, et al. End-of-life cell cycle arrest contributes to stochasticity of yeast replicative aging. FEMS Yeast Res. 2013;13:267–276. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JR, Murakami CJ, Olsen B, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Quantitative evidence for early life fitness defects from 32 longevity-associated alleles in yeast. Cell cycle. 2011a;10:156–165. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JR, Sutphin GL, Dulken B, Sim S, Kim JR, Robison B, Schleit J, Murakami CJ, Carr D, An EH, et al. Sir2 deletion prevents lifespan extension in 32 long-lived mutants. Aging Cell. 2011b;10:1089–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigan D, Hsu AL, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C. Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: a role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics. 2002;161:1101–1112. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzsch M, Tanner W. Protein-O-glycosylation in yeast: protein-specific mannosyltransferases. Glycobiology. 1997;7:481–486. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavidel A, Kislinger T, Pogoutse O, Sopko R, Jurisica I, Emili A. Impaired tRNA nuclear export links DNA damage and cell-cycle checkpoint. Cell. 2007;131:915–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature. 2000;408:255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JBS. New Paths in Genetics. 1 edn Harper; London: 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y, Li H, Li H, Lennarz WJ. Oligosaccharyltransferase directly binds to ribosome at a location near the translocon-binding site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:6945–6949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812489106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon LA, Schmeissner PJ, Dudaronek JM, Brown PA, Listner KM, Sakano Y, Paupard MC, Hall DH, Driscoll M. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature. 2002;419:808–814. doi: 10.1038/nature01135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutzler J, Schmid M, Bernard T, Henrissat B, Strahl S. Membrane association is a determinant for substrate recognition by PMT4 protein O-mannosyltransferases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:7827–7832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature. 2013;493:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M. Lessons on longevity from budding yeast. Nature. 2010;464:513–519. doi: 10.1038/nature08981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. Large-scale identification in yeast of conserved ageing genes. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2005;126:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Sir2-independent life span extension by calorie restriction in yeast. PLoS biology. 2004;2:E296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein M, Powers RW, III, Steffen KK, Westman EA, Hu D, Dang N, Kerr EO, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK. Regulation of yeast replicative life-span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients. Science. 2005;310:1193–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1115535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruegel U, Robison B, Dange T, Kahlert G, Delaney JR, Kotireddy S, Tsuchiya M, Tsuchiyama S, Murakami CJ, Schleit J, et al. Elevated proteasome capacity extends replicative lifespan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labunskyy VM, Gerashchenko MV, Delaney JR, Kaya A, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M, Gladyshev VN. Lifespan extension conferred by endoplasmic reticulum secretory pathway deficiency requires induction of the unfolded protein response. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre LR, Hansen M. Lessons from C. elegans: signaling pathways for longevity. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2012;23:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Lee RY, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Ruvkun G. A systematic RNAi screen identifies a critical role for mitochondria in C. elegans longevity. Nature genetics. 2003;33:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li X, Miller RA. ATF4 activity: a common feature shared by many kinds of slow-aging mice. Aging Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acel.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Miller RA. Elevated ATF4 Function in Fibroblasts and Liver of Slow-Aging Mutant Mice. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Shadel GS, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy B. Replicative and chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay VL, Li X, Flory MR, Turcott E, Law GL, Serikawa KA, Xu XL, Lee H, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, et al. Gene expression analyzed by high-resolution state array analysis and quantitative proteomics: response of yeast to mating pheromone. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:478–489. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MA, Mason AG, Guyenet SJ, Dang W, Garza RM, Ting MK, Moller RM, Berger SL, Kaeberlein M, Pillus L, et al. The SAGA Histone Deubiquitinase Module Controls Yeast Replicative Lifespan via Sir2 Interaction. Cell reports. 2014;8:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medawar PB. An Unsolved Problem of Biology. 1 edn H.K. Lewis and Co.; London: 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Martin-Montalvo A, Mercken EM, Palacios HH, Ward TM, Abulwerdi G, Minor RK, Vlasuk GP, Ellis JL, Sinclair DA, et al. The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 extends lifespan and improves health of mice fed a standard diet. Cell reports. 2014;6:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JF, Brignull HR, Weyers JJ, Morimoto RI. The threshold for polyglutamine-expansion protein aggregation and cellular toxicity is dynamic and influenced by aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152161099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen B, Murakami CJ, Kaeberlein M. YODA: software to facilitate high-throughput analysis of chronological life span, growth rate, and survival in budding yeast. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostlund G, Schmitt T, Forslund K, Kostler T, Messina DN, Roopra S, Frings O, Sonnhammer EL. InParanoid 7: new algorithms and tools for eukaryotic orthology analysis. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:D196–203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JB, van der Merwe G, Mangroo D. Protein kinase A is part of a mechanism that regulates nuclear reimport of the nuclear tRNA export receptors Los1p and Msn5p. Eukaryot Cell. 2014;13:209–230. doi: 10.1128/EC.00214-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Hu C, Anderson J, Bjork GR, Sarkar S, Hopper AK, Hinnebusch AG. Defects in tRNA processing and nuclear export induce GCN4 translation independently of phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:2505–2516. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2505-2516.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan X, Yu J, Bussey H, Stochaj U. The localization of nuclear exporters of the importin-beta family is regulated by Snf1 kinase, nutrient supply and stress. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1773:1052–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos FJ, Kaeberlein M. Ageing: A healthy diet for stem cells. Nature. 2012;486:477–478. doi: 10.1038/486477a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara NL, Datta AB, Berndsen CE, Zhang X, Yao T, Cohen RE, Wolberger C. Structural insights into the assembly and function of the SAGA deubiquitinating module. Science. 2010;328:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1190049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Hopper AK. tRNA nuclear export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: in situ hybridization analysis. Molecular biology of the cell. 1998;9:3041–3055. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder EA, Raimundo N, Shadel GS. Epigenetic silencing mediates mitochondria stress-induced longevity. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder EA, Shadel GS. Crosstalk between mitochondrial stress signals regulates yeast chronological lifespan. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2014;135:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle JS, Wood MD, Kaur M, Tobin DV, Sanchez Y. Proteins in the nutrient-sensing and DNA damage checkpoint pathways cooperate to restrain mitotic progression following DNA damage. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen HH, Hopper AK. Retrograde movement of tRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:11290–11295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503836102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms HS. Logarithmic increase in mortality as a manifestation of aging. Journal of gerontology. 1946;1:13–26. doi: 10.1093/geronj/1.1_part_1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ED, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Genome-wide identification of conserved longevity genes in yeast and worms. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2007;128:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ED, Tsuchiya M, Fox LA, Dang N, Hu D, Kerr EO, Johnston ED, Tchao BN, Pak DN, Welton KL, et al. Quantitative evidence for conserved longevity pathways between divergent eukaryotic species. Genome Res. 2008;18:564–570. doi: 10.1101/gr.074724.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen KK, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. Measuring replicative life span in the budding yeast. J Vis Exp. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen KK, MacKay VL, Kerr EO, Tsuchiya M, Hu D, Fox LA, Dang N, Johnston ED, Oakes JA, Tchao BN, et al. Yeast life span extension by depletion of 60s ribosomal subunits is mediated by Gcn4. Cell. 2008;133:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen KK, McCormick MA, Pham KM, Mackay VL, Delaney JR, Murakami CJ, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. Ribosome Deficiency Protects Against ER Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;191:107–118. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus KA, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. Replicative aging in yeast: the means to the end. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:29–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Maeda Y, Tashima Y, Kinoshita T. Inositol deacylation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins is mediated by mammalian PGAP1 and yeast Bst1p. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:14256–14263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira MC, Monteiro P, Jain P, Tenreiro S, Fernandes AR, Mira NP, Alenquer M, Freitas AT, Oliveira AL, Sa-Correia I. The YEASTRACT database: a tool for the analysis of transcription regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:D446–451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:W214–220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger M, Mesquita A, Caroll T, Marks L, Yang H, Zhang Z, Ludovico P, Burhans WC. Growth signaling promotes chronological aging in budding yeast by inducing superoxide anions that inhibit quiescence. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:709–726. doi: 10.18632/aging.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons of grouped data by ranking methods. J Econ Entomol. 1946;39:269. doi: 10.1093/jee/39.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Yang T, Baur JA, Perez E, Matsui T, Carmona JJ, Lamming DW, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA, Rosenzweig A, et al. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell. 2007;130:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos ME, Bennett CF, Kaeberlein M. Genome-Wide RNAi Longevity Screens in Caenorhabditis elegans. Current genomics. 2012;13:508–518. doi: 10.2174/138920212803251391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Tsuchiyama S, Yang C, Bulteau AL, He C, Robison B, Tsuchiya M, Miller D, Briones V, Tar K, et al. Proteasomes, Sir2, and Hxk2 form an interconnected aging network that impinges on the AMPK/Snf1-regulated transcriptional repressor Mig1. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Chabes A, Domkin V, Thelander L, Rothstein R. The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1 is a new target of the Mec1/Rad53 kinase cascade during growth and in response to DNA damage. EMBO J. 2001;20:3544–3553. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.