Abstract

Objectives The recurrence of meningiomas is a crucial aspect that must be considered during the planning of treatment strategy. The Simpson grade classification is the most relevant surgical aspect to predict the recurrence of meningiomas. We report on a series of patients with recurrent skull base meningiomas who were treated with the goal of radical removal.

Design A retrospective study.

Setting Hospital Ernesto Dornelles, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Participants Patients with recurrent skull base meningiomas.

Main Outcomes Measures The goal of obtaining aggressive resection (i.e., Simpson grades I and II).

Results The average age was 54 years, the mean follow-up period was 52.1 months, and Simpson grades I and II were obtained in 82%. The overall mortality was 5.8%. Transient cranial nerve deficits occurred in 11.7%; the definitive morbidity was also 5.8%. A second recurrence occurred in 5.8%.

Conclusions Radical removal of recurrent skull base meningiomas is achievable and should be considered an option with a good outcome and an acceptable morbidity. The common surgical finding that was responsible for recurrence in this study was incomplete removal during the first surgery. We recommend extensive dura and bone removal in the surgical treatment of such recurrent lesions.

Keywords: skull base, meningioma, Simpson grade, recurrence, brain tumor

Introduction

The recurrence in meningiomas that have been treated surgically is a concern during the follow-up period. Numerous studies suggest that the biological behavior is less determined by the histopathologies of benign meningiomas and more strongly related to molecular cytogenetic, flow cytometry, and hormonal receptor findings.1 2 3 4 5 With the exceptions of a few references in the literature, the consensus is that Simpson grade resection is the most relevant surgical aspect in predicting the possible recurrence of meningiomas.1 2 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 We report a series of 17 recurrent skull base meningiomas in which the most radical removal possible was attempted and discuss the relevant clinical and surgical aspects of the cases.

Methods

A retrospective study of patients operated on between 2004 and 2014 was performed. The inclusion criteria were a benign meningioma (World Health Organization [WHO] grade I), a previous documented surgery, and a surgery for a recurrent or regrowth tumor that was performed by the first author (C.E.S.). Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas were excluded. The data related to the first interventions performed in other departments were reviewed, and special attention was given to the Simpson grade, additional radiation treatment, and the site of the meningioma prior to the recurrence of the tumor. We reviewed the medical records, operative reports, radiologic examinations, and follow-up information of the cases. All patients underwent surgery for a recurrent meningioma in our department with the intent of the most extensive radical removal possible including dura and bone invasions.

The patients underwent several skull base approaches according to the site of the recurrence of the meningioma. Olfactory groove (OG) lesions were removed through supraorbital, cranioorbital, and supraorbital bifrontal approaches; sphenoorbital meningiomas (SOMs) were removed via the cranioorbital zygomatic (COZ) approach; temporal floor meningiomas were operated on through the zygomatic and COZ approaches; cavernous sinus lesions were treated via the COZ approach; petroclival meningiomas were removed through the posterior petrosal approach; and torcular and tentorial meningiomas were removed through the suboccipital and transmastoid retrosigmoid approaches.

Results

Between 2004 and 2014, 17 recurrent meningiomas were operated on in 16 patients. Thirteen patients were previously operated on in other departments. The group was composed of the following lesions: five OG, three sphenoorbital, two temporal floor, two cavernous sinus, two tentorial, two petroclival, and one torcular lesion. The group was composed of 13 women and 3 men with an average age of 54 years (range: 31–69 years). The mean follow-up period was 52.1 months (range: 6–120 months). Simpson grades I and II were obtained following 82% of the surgeries for the recurrent meningiomas. The first surgeries performed on the meningiomas included in this study obtained resection Simpson grades III and IV in 88% of the cases. Thirteen patients were operated on in other departments; only three cases included in this series were treated previously in our department. The meningiomas that had previously been irradiated composed 41% of the cases. The recurrent meningiomas were > 4 cm in 52% of the cases. Subsequent recurrence after aggressive removal (Simpson grade I) occurred in 5.8% of the cases within the evaluated period.

The overall mortality was 5.8% (one case of a giant meningioma of the torcula that had previously been irradiated and presented as a serious posterior fossa venous infarction during the postoperative period). The definite morbidity was also 5.8%, and this case included left hemiparesis and cranial nerve VI and VII palsies in a large previous irradiated petroclival meningioma. Transient cranial nerve deficits occurred in 11.7% of the patients, and complete recoveries were observed within 3 months of follow-up. Tables 1 and 2 present the findings of the series.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients with recurrent meningiomas.

| Case | Sex | Age, y | Site | Approach | Size, cm | Simpson grade first surgery | Previous radiation treatment | Simpson grade recurrence surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 40 | OG | SPOBF | > 4 | 3 | Y | I |

| 2 | F | 31 | OG | SPO | > 4 | 3 | N | I |

| 3 | M | 50 | OG | SPOBF | > 4 | 4 | N | III |

| 4 | M | 50 | OG | SPOBF | < 2 | 1 | N | I |

| 5 | F | 58 | OG | CO | > 4 | 3 | N | I |

| 6 | F | 67 | SO | COZ | > 4 | 3 | Y | I |

| 7 | F | 52 | SO | COZ | 2–4 | 3 | Y | I |

| 8 | F | 62 | SO | COZ | 2–4 | 3 | N | I |

| 9 | F | 41 | TF | Z | > 4 | 3 | Y | I |

| 10 | F | 48 | TF | COZ | 2–4 | 3 | Y | III |

| 11 | F | 52 | CS | COZ | > 4 | 4 | N | III |

| 12 | M | 58 | CS | COZ | 2–4 | 4 | N | II |

| 13 | F | 69 | PC | PP | 2–4 | 4 | N | II |

| 14 | F | 54 | PC | PP | > 4 | 4 | Y | II |

| 15 | F | 60 | TOR | SO | > 4 | 4 | Y | I |

| 16 | F | 65 | TEN | TMRS | 2–4 | 3 | N | I |

| 17 | F | 65 | TEN | TMRS | 2–4 | 3 | N | II |

Abbreviations: CO, cranioorbital; COZ, cranioorbital zygomatic; CS, cavernous sinus; F, female; M, male; OG, olfactory groove; PC, petroclival; PP, posterior petrosal; SO, suboccipital; SO, sphenoorbital; SPO, supraorbital; SPOBF, supraorbital bifrontal; TEN, tentorial; TF, temporal floor; TOR, torcula; TMRS, transmastoid retrosigmoid; Z, zygomatic.

Table 2. Morbidity and mortality of the series.

| Case | Site | Morbidity/Mortality | New DEF CND | Transient CND |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | TF | – | – | III |

| 12 | CS | – | – | III AND IV |

| 14 | PC | LEFT HEMIP | VI AND VII | – |

| 15 | TOR | OBIT | – | – |

Abbreviations: CND, cranial nerve deficit; CS, cavernous sinus; HEMIP, hemiparesis; OBIT, death; PC, petroclival; TF, temporal floor; TOR, torcula.

Discussion

The seminal paper of Simpson highlighted the importance of radical removal during the surgical treatment of meningiomas in the prevention of tumor recurrence.14 In convexity meningiomas, the achievement of radical removal is more feasible, and in some selected cases, additional margins of the dura are resected, which leads to grade zero removal.11 In skull base meningiomas, such aggressive resection is not possible in many cases due to the surrounding vital neurovascular structures. Moreover, there is a trend to be less radical during the removal of skull base meningiomas due to concerns related to the quality of life of the patients and the goal of reducing surgical morbidity.15 Stereotactic radiosurgery has been used as primary or adjuvant therapy in many cases of benign skull base meningiomas, and the recurrence of such cases results in lesions that are clearly difficult to manage.16 17 In contrast, numerous series have considered the application of modern skull base techniques, fluorescent markers, neuronavigational systems, and transoperative imaging that have reported high rates of complete removal of skull base meningiomas and low morbidity rates.6 18 19 20 21 22

The most important aspect during the revisions of the patients included in this series was related to previous surgeries that were performed in other departments in most of the cases (13/16 patients); in 88%, Simpson grades III and IV were achieved in the previous surgeries, and these resections were considered satisfactory at that time by the respective departments. We consider true recurrence of the meningiomas when a Simpson grade III removal was previously performed and regrowth of the tumors in cases with previous Simpson grade IV removals. Six patients included in the present series received partial removals (Simpson IV) during their first surgeries (Table 1). We included such cases because the residual tumors, both in Simpson grades III and IV, increase the risk of recurrence/regrowth of the lesions, compared with Simpson grades I and II. The correct application of the Simpson concept to skull base meningiomas is important. Some authors have described gross total removals (GTRs) and suggested that such patients are radically treated in terms of the risk of recurrence. Typically, the patients included in GTR groups are Simpson grade III, and their recurrence rates are obviously higher than those of patients for whom true total removal is achieved; here, true total removal includes the resection of all dura and bone involvement. In hard consistent tumors of the cavernous sinus and petroclival regions, radical resection of the dura and bone is impossible to achieve in many cases. In such tumors, GTR is reasonable and a successful surgical treatment. In contrast, the analysis of our series revealed that most of the cases were OG, temporal floor, and tentorial meningiomas (i.e., sites for which Simpson grades I and II are achievable with a minimal risk for serious morbidity). Considering that the mean age of the group was 54 years, the life expectancy for most of the cases during their first surgical treatments was high. In our opinion, the concerns related to reducing the transoperative risks and maintaining quality of life led to incorrect decisions in terms of the best surgical options for these patients in the previous departments that operated on such cases. It is important to consider that radically treated meningiomas can result in high recurrence-free rates at 5 and 20 years of follow-up.1 23

Among the recurrent OG meningiomas, four cases presented with the common feature of bone involvement of the tumors that was not removed during the first surgery. This feature has also been observed in other series of recurrent OG meningiomas and represents the most relevant finding for failure of the surgical control of the disease.12 15 In one patient who underwent surgery in our department, a giant meningioma was removed with the dural and bone involvement of the anterior fossa, and a small recurrence occurred 6 years after surgery in the most anterior part of the anterior fossa near the falx. This case likely represents a regional multicentricity of the meningioma because the recurrence occurred more anteriorly, and the follow-up of this case was altered to observe any other recurrence. The OG meningiomas were treated through the supraorbital approach in two cases, through the cranioorbital approach, which is a variation of the COZ approach that includes only the cranioorbital flap in two cases, and through the supraorbital bifrontal approach in one case. The approaches were selected according to the extension of the tumors into the surrounding neurovascular structures and rhinopharynx. In three cases, the dura of the anterior fossa and the hyperostotic bone were totally removed, and the anterior skull base was reconstructed using pericranial flaps and fascia lata. In one case of a comatose patient with a giant recurred meningioma, a decompressive supraorbital bifrontal approach and removal of the mass was performed without removal of the dura and anterior fossa bone due to the poor clinical condition of the patient.

SOMs are challenging lesions in terms of radical removal because orbital and cavernous sinus structures are involved in many cases. In all three cases of SOM, the previous surgeries removed the intracranial masses, and residual tumors were present in the bones of the sphenoid ridge and orbit. Over the subsequent months, the patients developed exophthalmos, visual disturbances, and eye pain, and magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography revealed orbital progressions of the meningiomas. The first surgical approach for SOM should include orbital bone removal even of cases of very minor hyperostotic changes because hyperostosis indicates tumor bone invasion and a higher rate of recurrence.13 24 COZ approaches were utilized in all three cases of SOM and included radical resections of the dura and bone involvements (Figs. 1 and 2). SOMs that involve the medial portion of the sphenoid wing represent more challenging lesions due to the involvement of the neurovascular structures.25 26 With the exception of clinoidal meningiomas arising from the subclinoidal dura (type I of Al-Mefty), which are extra-arachnoidal and tend to be more adherent to the internal carotid artery, the clinoidal type II and the meningiomas of the medial portion of the sphenoid wing should be considered different lesions compared with SOMs, due to their distinct origin. In such meningiomas, there is an arachnoidal plane between the neurovascular structures and the tumors. The use of microsurgical techniques via the arachnoidal plane allows for the removal of such meningiomas with low morbidity rates.19

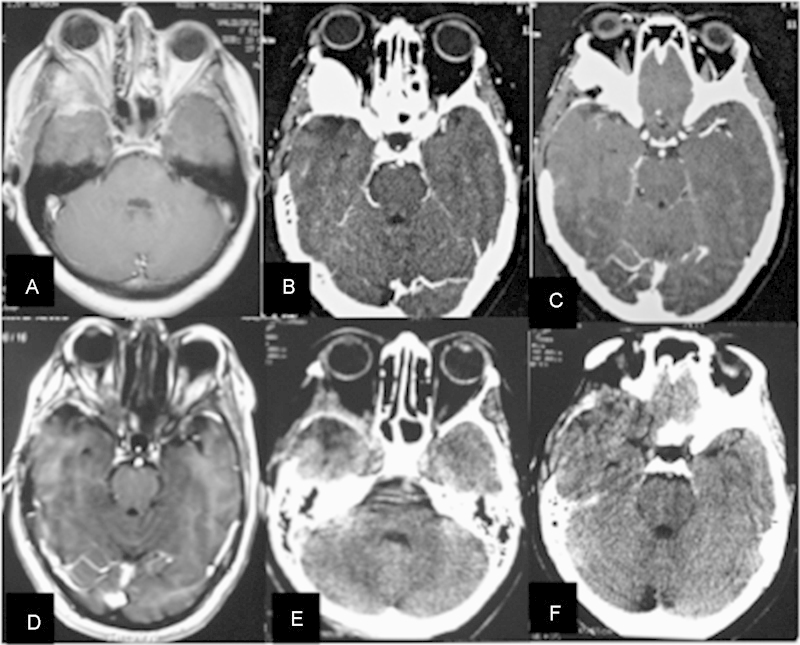

Fig. 1.

Sphenoorbital meningioma. (A–C) Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a right sphenoorbital recurrence. (D–F) Postoperative MRI and CT scan demonstrating radical removal of the dura and bone involvement by the tumor.

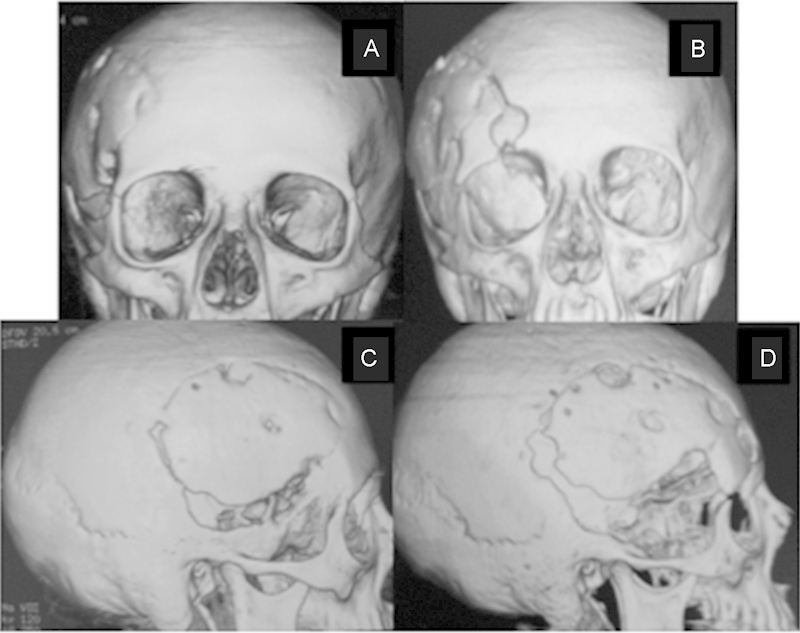

Fig. 2.

Sphenoorbital meningioma. (A) Preoperative coronal three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating a right sphenoorbital recurrence. Note the involvement of the orbital bones by the tumor. (B) Postoperative coronal 3D CT scan demonstrating a complete orbital bone removal of the tumor through a cranioorbital zygomatic approach. (C) Preoperative sagittal 3D CT scan demonstrating the sphenoid wing involvement, inferior to craniotomy. (D) Postoperative sagittal 3D CT scan demonstrating the aggressive bone removal.

One patient with a temporal floor meningioma recurred two times during the reviewed period. The first recurrence was a giant infratemporal invasion that followed a Simpson grade III removal and conformational radiotherapy in another department. The tumor was totally removed through the zygomatic approach with aggressive bone resection of the temporal floor. Seven years later, the patient presented with a new recurrence in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and medial portion of the temporal floor. This case was the only recurrence that followed a second surgery with a Simpson grade I removal (5.8%). A GTR removal of the mass was performed through the COZ approach and achieved a Simpson grade III removal with a transient sixth nerve palsy that resolved in 3 months. This case illustrates the importance of the first surgery for the local control of meningiomas. The absence of the arachnoidal plane and associated postirradiation disturbances make radical removal virtually impossible without definitive morbidity. We have closely followed this patient over the last 3 years and are concerned about the next recurrence of this irradiated meningioma, which is at risk for malignant progression.16 17

The giant torcular meningioma that had been partially removed and previously irradiated presented with a total occlusion of the torcula on magnetic resonance venography (MRV). The radical en bloc removal of the torcula and tentorial involvements led to a massive posterior fossa venous infarct, and the patient died in the postoperative period.

The cavernous sinus and petroclival recurrent meningiomas were removed as radically as possible. One cavernous sinus meningioma with a very hard consistency underwent GTR (Simpson grade III). The second cavernous sinus meningioma was a soft tumor and was removed via peeling of the middle fossa and the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus, which was considered a Simpson grade II resection. This patient presented with transient cranial nerve III and IV palsies. Both giant recurrent petroclival meningiomas had previously been operated on with partial resections. The rescue surgery achieved a Simpson grade II, but one previously irradiated patient developed a venous infarction of the anterolateral portion of the pons and presented with definite hemiparesis and sixth and seventh nerve palsies. Cavernous sinus and petroclival meningiomas are the most challenging tumors because of their neurovascular involvements. Hard consistent tumors and irradiation are limitations for total removal in such anatomical sites, and the recurrence and morbidity are higher than those observed for other skull base meningiomas.2 7 8 27 28 29

The tentorial recurrent meningiomas were moderate size lesions with no previous irradiation and favorable removals. One patient was previously operated on in our department and received an intentional Simpson grade III removal due to involvement of a patent transverse sinus. After 2 years, MRV demonstrated occlusion of the sinus and recurrence of the meningioma. We removed the tumor and the involved tentorium and transverse sinus en bloc.

The efforts to achieve the most radical resections possible in recurrent and regrowth meningiomas were reinforced by the ages of the patients. Younger patients should be treated while considering that longer follow-up periods are favorable for recurrence in any modality of treatment for meningiomas. The surgical modality should offer the best chance for local control and thus should be total removal. The chance of surgical control of the disease in recurrence is lower, but when there is a possibility of achieving extensive resection with lower morbidity, we believe this is the best surgical option.

The mean follow-up period of the patients was 52.1 months. Three patients in the series underwent surgery in our department prior to recurrence. In one tentorial meningioma that was removed with the preservation of a patent transverse sinus with tumor involvement (Simpson grade III), recurrence was evident at 24 months. In one OG meningioma, a small recurrence was diagnosed 6 years after a supposed Simpson grade I resection, and one temporal floor meningioma recurred for the second time 7 years after a radical removal. These findings are consistent with those in the literature, which suggests the importance of long follow-up periods for benign meningiomas and supports the concept that Simpson grades I and II are related to long periods of local tumor control. An extended follow-up period is important to evaluate the success rates of all modalities of treatment that are proposed for the management of such tumors. Short follow-ups periods tend to overestimate any treatment effect in the control of the meningiomas (Fig. 3).1 9 10 14

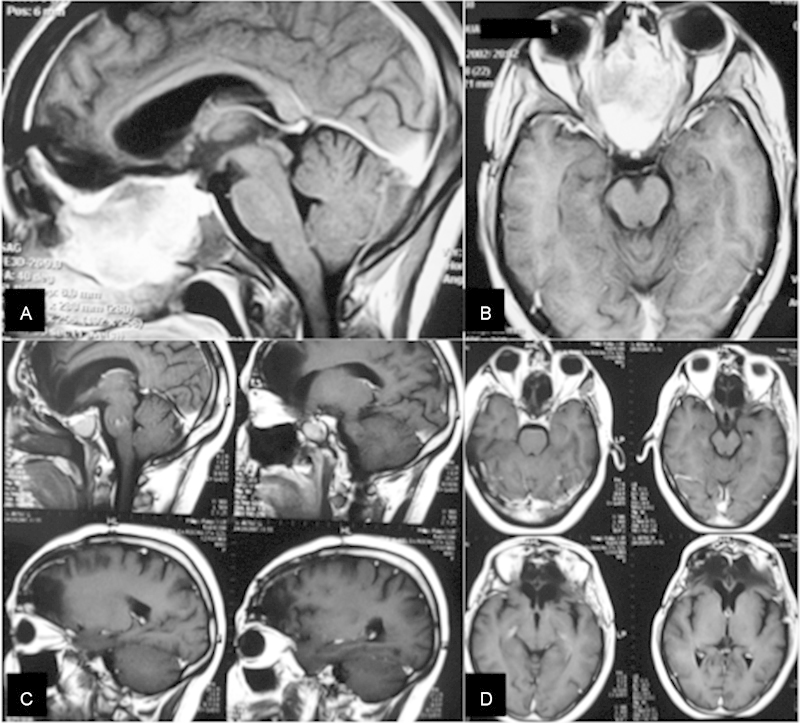

Fig. 3.

Olfactory groove (OG) meningioma. (A, B) Preoperative sagittal and axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a recurrent (OG) meningioma. (C, D) Postoperative sagittal and axial MRI 8 years after the radical removal of the tumor and bone involvement of the anterior fossa.

There are studies presenting aggressive meningioma malignant progression, radiation-induced meningiomas, and genetic abnormalities related to radiation-associated meningiomas. Such malignant evolution is related to low, medium, and high radiation doses.16 17 30 Nowadays, we believe that radiosurgery is an important tool for the multidisciplinary approach to complex skull base meningiomas, as adjuvant therapy after partial microsurgical removal and meningiomas grade II and III (WHO). However, a large number of patients are submitted to radiosurgery, with different protocols and radiation delivery, as primary therapy for skull base meningiomas, and long term follow-up studies (> 10 years) will indicate the real potential of malignant progression of such benign irradiated meningiomas.16 17 30

Currently, we follow patients with benign meningiomas and consider the Ki-67 index, hormonal receptors, and molecular cytogenetics to predict their recurrence. In cases in which recurrences are diagnosed, we consider surgical removal as the first treatment option. When surgical removal is not possible, the cytogenetic profile is unfavorable, and regrowth of the meningioma is documented, we consider radiosurgery. In our department, radiosurgery is avoided as the first option for benign meningiomas and as immediate adjuvant therapy even in cases of less radical surgeries. Depending on the molecular findings and the proliferating index, in favorable cases, such tumors remain stable and with no recurrence over long periods.1 In patients who have undergone radical removal, local control is even better, which justifies the avoidance of submitting them to irradiation.1 10 17 18

Conclusions

Radical removal in recurrent skull base meningiomas is achievable and should be considered an option with good outcomes and acceptable morbidity. The common surgical finding responsible for recurrence in this study was incomplete removal during the first surgery. We recommend extensive dura and bone removal in the surgical treatment of such recurrent lesions whenever possible to obtain higher rates of local control.

References

- 1.Adegbite A B, Khan M I, Paine K WE, Tan L K. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurosurg. 1983;58(1):51–56. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.1.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almefty R, Dunn I F, Pravdenkova S, Abolfotoh M, Al-Mefty O. True petroclival meningiomas: results of surgical management. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(1):40–51. doi: 10.3171/2013.8.JNS13535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ketter R, Henn W, Niedermayer I. et al. Predictive value of progression-associated chromosomal aberrations for the prognosis of meningiomas: a retrospective study of 198 cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(4):601–607. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.4.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J K, Niazi Z, Couldwell W T. Reconstruction of the skull base after tumor resection: an overview of methods. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(5):e9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.12.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ragel B T, Jensen R L. Molecular genetics of meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(5):E9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.al-Mefty O, Anand V K. Zygomatic approach to skull-base lesions. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(5):668–673. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.5.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva C E, da Silva J LB, da Silva V D. Use of sodium fluorescein in skull base tumors. Surg Neurol Int. 2010;1:70. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.72247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva C E, da Silva V D, da Silva J L. Sodium fluorescein in skull base meningiomas: a technical note. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;120:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMonte F, Smith H K, al-Mefty O. Outcome of aggressive removal of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;81(2):245–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erkmen K, Pravdenkova S, Al-Mefty O. Surgical management of petroclival meningiomas: factors determining the choice of approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(2):E7. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.2.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ildan F, Erman T, Göçer A I. et al. Predicting the probability of meningioma recurrence in the preoperative and early postoperative period: a multivariate analysis in the midterm follow-up. Skull Base. 2007;17(3):157–171. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinjo T al-Mefty O Kanaan I Grade zero removal of supratentorial convexity meningiomas Neurosurgery 1993333394–399.; discussion 399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obeid F Al-Mefty O Recurrence of olfactory groove meningiomas Neurosurgery 2003533534–542.; discussion 542–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20(1):22–39. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feiz-Erfan I, Han P P, Spetzler R F. et al. The radical transbasal approach for resection of anterior and midline skull base lesions. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(3):485–490. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.3.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mefty O, Topsakal C, Pravdenkova S, Sawyer J R, Harrison M J. Radiation-induced meningiomas: clinical, pathological, cytokinetic, and cytogenetic characteristics. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(6):1002–1013. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.6.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couldwell W T, Cole C D, Al-Mefty O. Patterns of skull base meningioma progression after failed radiosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(1):30–35. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Mefty O. Supraorbital-pterional approach to skull base lesions. Neurosurgery. 1987;21(4):474–477. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Mefty O. Clinoidal meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(6):840–849. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Mefty O, Fox J L, Smith R R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22(3):510–517. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choy W, Kim W, Nagasawa D. et al. The molecular genetics and tumor pathogenesis of meningiomas and the future directions of meningioma treatments. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;30(5):E6. doi: 10.3171/2011.2.FOCUS1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Silva C E, da Silva J LB, da Silva V D. Skull base meningiomas and cranial nerves contrast using sodium fluorescein: a new application of an old tool. J Neurol Surg B. 2014;75(4):255–260. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jääskeläinen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26(5):461–469. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oya S, Kawai K, Nakatomi H, Saito N. Significance of Simpson grading system in modern meningioma surgery: integration of the grade with MIB-1 labeling index as a key to predict the recurrence of WHO Grade I meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(1):121–128. doi: 10.3171/2012.3.JNS111945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sughrue M E, Rutkowski M J, Chen C J. et al. Modern surgical outcomes following surgery for sphenoid wing meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(1):86–93. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.JNS11539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oya S, Sade B, Lee J H. Sphenoorbital meningioma: surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(5):1241–1249. doi: 10.3171/2010.10.JNS101128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakata K Al-Mefty O Yamamoto I Venous consideration in petrosal approach: microsurgical anatomy of the temporal bridging vein Neurosurgery 2000471153–160.; discussion 160–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekhar L N, Burgess J, Akin O. Anatomical study of the cavernous sinus emphasizing operative approaches and related vascular and neural reconstruction. Neurosurgery. 1987;21(6):806–816. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekhar L N, Sen C N, Jho H D, Janecka I P. Surgical treatment of intracavernous neoplasms: a four-year experience. Neurosurgery. 1989;24(1):18–30. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claus E B Calvocoressi L Greenhalgh S et al. Genetic changes in radiation-associated meningiomas Neuro-Oncol 20141603iii125165195 [Google Scholar]