Abstract

Background

Few studies have reported odds of mortality for hospitalized premature infants stratified by postnatal age and adjusted for severity of illness. Our objective was to examine day-by-day mortality of premature infants in a large multicenter cohort of infants, adjusted for demographics, severity of illness, and receipt of therapeutic interventions.

Methods

This was a multicenter cohort study of infants cared for in 362 neonatal intensive care units with a shared clinical data warehouse from 1997 to 2013. We included all inborn infants born at 22–29 weeks’ gestational age with available mortality discharge data. We report the point prevalence of survival to hospital discharge stratified by gestational and postnatal age.

Results

We identified 64,896 infants, of whom 55,348 (85%) survived to hospital discharge. Survival increased with gestational and postnatal age, until infants reach a postmenstrual age of approximately 37 weeks, after which survival began to decrease. Overall survival increased over time (80% in 1997 to 88% in 2013, P<.001).

Conclusions

Given the known association between gestational age and postnatal age, survival predictions should be adjusted for both covariates.

Keywords: mortality, gestational age, premature infant

1. INTRODUCTION

One in three premature infants with an extremely low birth weight (ELBW; <1000 g) who are admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) will not survive to hospital discharge [1]. Lower gestational age (GA) and need for therapeutic interventions are associated with increased mortality [1–3].

Mortality prediction is an essential tool to guide parental counseling and treatment of premature infants. Prediction of in-hospital mortality based on infant characteristics at birth including GA, birth weight, sex, singleton birth, and receipt of antenatal steroids has been well established [3]. These variables are included in the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network (NRN) outcomes estimator, which generates a range of possible survival probabilities with or without neurodevelopmental impairment, based on these infant characteristics [4]. An important limitation of this prediction tool is its exclusion of infants >25 weeks’ GA and focus on risk prediction immediately after birth.

In-hospital mortality decreases significantly if an infant survives the first 3 days of life [5]. As a consequence, studies have incorporated infant characteristics obtained after birth and have attempted to predict in-hospital mortality at different postnatal ages (PNAs) [6,7]. These studies have focused on the characteristics of the prediction model and the relative importance of individual predictor variables. Other studies have reported on the actual day-by-day survival of infants but have not reported risk adjusted predictions [8].

The purpose of our study was to describe the daily point prevalence of survival to hospital discharge of premature infants in a large multicenter cohort of infants, adjusted for GA. We hypothesized that increasing GA and PNA were associated with decreased in-hospital mortality.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data Source

We used a database derived from electronic medical records and daily progress notes generated by clinicians on all infants cared for by the Pediatrix Medical Group in 362 NICUs in North America from 1997 to 2013. Data on multiple aspects of care were entered into a shared electronic medical record to generate admission and daily progress notes and discharge summaries. Information regarding maternal history, demographics, medications, laboratory results, diagnoses, and procedures was then transferred to the Pediatrix clinical data warehouse for quality improvement and research purposes [9]. We included infants 22–29 weeks’ GA cared for at one hospital and discharged between 1997–2013. We excluded outborn infants, those transferred to another hospital, and those with severe congenital anomalies (Figure 1). The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Fig. 1.

Study population.

2.2. Definitions

We defined mortality as death prior to discharge from the NICU or 120 days, whichever was first, and described GA in weeks and PNA in days. Antenatal steroid exposure was defined as maternal exposure to steroids during pregnancy. We defined daily inotropic support as the need for any inotropic medication (epinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine, amrinone, milrinone, and norepinephrine) on a given day. Daily oxygen support was defined as the highest fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) administered on a given day, and we categorized the variable as follows: 21%, 22% to 30%, or >30%. We defined small for gestational age (SGA) as previously described [10].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The unit of observation for this analysis was an infant day in the NICU. We censored observations after 120 days of life due to the small sample size and heterogeneous nature of infants hospitalized after that time. We used summary statistics including medians and 25th and 75th percentiles to describe continuous variables, and frequency counts and percentages to describe categorical variables. We compared infant characteristics between survivors and non-survivors using chi-square tests of association and Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

We calculated point prevalence of survival to NICU discharge by GA and birth year, and compared mortality prior to NICU discharge over time stratified by GA using the Cochran–Armitage test for trend. We calculated point prevalence of survival to NICU discharge stratified by GA at prespecified postnatal time points (day of life [DOL] 7, 30, 60, 90, and 120). An infant was included in the denominator for point prevalence calculation if the child was still hospitalized on that day, and the infant was excluded if discharged, alive or dead, prior to that day. We conducted all analyses using Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX) and considered a P<.05 statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

Of the 64,896 infants included in our study, 55,348 (85%) survived to hospital discharge. Median (25th, 75th percentile) GA and birth weight were higher in survivors compared to non-survivors (GA: 28 weeks [26,29] vs. 24 weeks [23,26], P<.001; birth weight: 1000 g [800, 1200] vs. 650 g [546, 794], P<0.001). Survivors were less likely to be SGA or male, and more likely to have received antenatal steroids and be born via cesarean section (Table 1). Median PNA at death was 6 days (1, 19) and 90% of deaths occurred in the first 41 days of life. On the day of death, 93% of infants received mechanical ventilation and 87% received FiO2 >30%, but only 35% received inotropes.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Survived n=55,348 | Died n=9548 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks), No./No. (%) | ||

| 22 | 71/485 (15) | 414/485 (85) |

| 23 | 1152/3223 (36) | 2071/3223 (64) |

| 24 | 3596/6121 (59) | 2525/6121 (41) |

| 25 | 5587/7256 (77) | 1669/7256 (23) |

| 26 | 7319/8502 (86) | 1183/8502 (14) |

| 27 | 9573/10,330 (93) | 757/10,330 (7) |

| 28 | 12,742/13,290 (96) | 548/13,290 (4) |

| 29 | 15,308/15,689 (98) | 381/15,689 (2) |

| Birth weight (g), No./No. (%) | ||

| <500 | 715/2110 (34) | 1395/2110 (66) |

| 500–750 | 10,127/15,750 (66) | 5623/15,750 (34) |

| 751–1000 | 17,083/19,061 (90) | 1978/19,061 (10) |

| 1001–1500 | 25,528/26,374 (97) | 846/26,374 (3) |

| >1500 | 1854/1893 (98) | 39/1893 (2) |

| SGA, No./No. (%) | 6139/8401 (73) | 2262/8401 (27) |

| Male, No./No. (%) | 28,593/34,091 (84) | 5498/34,091 (16) |

| Antenatal steroids, No./No. (%) | 46,126/52,519 (88) | 6393/52,519 (12) |

| Cesarean section, No./No. (%) | 38,734/44,870 (86) | 6136/44,870 (14) |

| 5-minute Apgar score, No./No. (%) | ||

| 0–3 | 1834/3616 (51) | 1782/3616 (49) |

| 4–6 | 9192/12,373 (74) | 318112,373 (26) |

| 7–10 | 43,460/47,818 (91) | 4358/47,818 (9) |

SGA, small for gestational age.

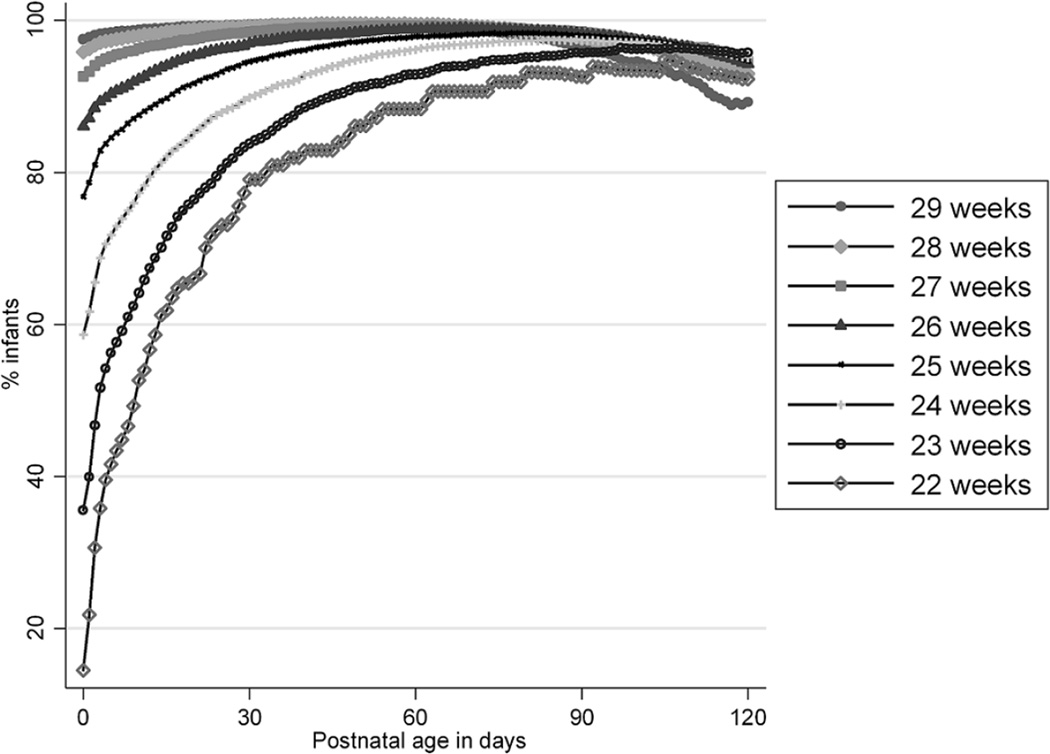

Survival increased with GA from 71/485 (15%) for infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation to 15,308/15,689 (98%) for infants born at 29 weeks’ gestation (Table 1). Survival to hospital discharge increased with PNA (Table 2 and Figure 2). This increase was more pronounced in lower GA infants and most significant in the first week of life: overall survival on DOL 0 was 85% compared to 92% on DOL 7, 97% on DOL 30, 98% on DOL 60, 98% on DOL 90, and 95% on DOL 120. Survival reached a peak and started to decline as infants aged and remained hospitalized. Survival was highest at a PNA corresponding to a postmenstrual age (PMA) of roughly 37 weeks: DOL 105 for 22-week GA infants (PMA=37 weeks); DOL 107 for 23-week GA infants (PMA=38 2/7 weeks); DOL 89 for 24-week GA infants (PMA=36 5/7 weeks); DOL 77 for 25-week GA infants (PMA=36 weeks); DOL 68 for 26-week GA infants (PMA=35 5/7 weeks); DOL 56 for 27-week GA infants (PMA=35); DOL 49 for 28-week GA infants (PMA=35 weeks); and DOL 36 for 29-week GA infants (PMA=34 1/7 weeks). Mortality for the 4239 infants hospitalized for ≥120 days was 5.4%, with a median PNA at death in this subgroup of 161 days (142, 189).

Table 2.

Point prevalence of survival by gestational and postnatal age (DOL).

| Gestational age (weeks) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 n=485 |

23 n=3223 |

24 n=6121 |

25 n=7256 |

26 n=8502 |

27 n=10,330 |

28 n=13,290 |

29 n=15,689 |

P | |

| DOL 0, No./No. (%) | 69/475 (15) |

1115/3134 (36) |

3511/5986 (59) |

5467/7112 (77) |

7153/8314 (86) |

9396/10,148 (93) |

12,479/13,01 7 (96) |

14,990/15,363 (98) |

<.001 |

| DOL 7, No./No. (%) | 69/154 (45) |

1130/1908 (60) |

3564/4822 (74) |

5539/6466 (86) |

7266/7978 (91) |

9523/9953 (96) |

12,668/12,96 7 (98) |

15,220/15,439 (99) |

<.001 |

| DOL 30, No./No. (%) | 68/86 (79) |

1119/1335 (83) |

3548/3950 (90) |

5521/5840 (95) |

7247/7470 (97) |

9440/9583 (98) |

12,472/12,56 6 (99) |

14,595/14,674 (99) |

<.001 |

| DOL 60, No./No. (%) | 68/77 (88) |

1114/1199 (93) |

3526/3664 (96) |

5442/5562 (98) |

6837/6918 (98) |

7429/7482 (99) |

6680/6712 (>99) |

4075/4107 (>99) |

<.001 |

| DOL 90, No./No. (%) | 63/68 (93) |

1067/1115 (96) |

2964/3041 (97) |

3398/3467 (98) |

2781/2831 (98) |

1812/1840 (98) |

1122/1149 (98) |

526/546 (96) |

<.001 |

| DOL 120, No./No. (%) | 36/39 (92) |

585/611 (96) |

1142/1201 (95) |

935/988 (95) |

639/678 (94) | 356/376 (95) |

225/242 (93) |

108/121 (89) |

.15 |

Fig. 2.

Point prevalence of survival by postnatal age for hospitalized infants.

Overall survival increased over time from 477/599 (80%) in 1997 to 4589/5221 (88%) in 2013 (P<.001 from Cochran–Armitage test for trend). When analyzed separately by GA, this trend was significant for all infants (all P<.01) except for the 22-week GA cohort (P=0.08). The latter finding may be related to the smaller sample size (n=485 infants) in the 22-week GA cohort.

4. DISCUSSION

We conducted the largest (to our knowledge) study of daily survival to hospital discharge in premature infants. Overall survival was 85% and increased over time. Survival was lowest on the day of admission and increased significantly through DOL 30. As anticipated, increasing GA was associated with improved survival initially. More significantly, we found that the relationship between GA and survival changed with increasing PNA. Regardless of GA, when hospitalized beyond a PMA near term, infants had lower probability of survival to hospital discharge.

Mortality for ELBW infants remains high. Among 5418 infants from the NRN ELBW registry born between 2006 and 2009, mortality was 34% and ranged from 11% to 53% across the 16 participating centers [1]. Results were similar in a cohort of 355,806 infants ≤1500 g birth weight treated at Vermont Oxford Network participating centers [11]. Mortality for the subset of infants ≤1000 g ranged from 12% to 44%. Findings from both studies are comparable to the 15% hospital mortality observed in our cohort. A combination of infant factors (e.g., GA or birth weight) and therapeutic interventions (e.g., surfactant or prenatal steroids) are known to affect infant mortality [3]. The initial response to these therapeutic interventions may be one of the most important determinants of survival. Indeed, very premature infants are often admitted to the NICU for a trial of therapy, after which their anticipated outcome is reevaluated [12]. This strategy, and the vulnerability of infants immediately after birth, likely explain the high rates of death in the first days of life. In a study of 429 ELBW infants with an overall mortality rate of 53%, the vast majority of deaths (80%) occurred in the first 3 days after birth [5]. Findings were similar in a prospective study of 3419 infants born at ≤30 weeks’ GA at one of 17 Canadian NICUs [13]. Actuarial survival curves demonstrated that the highest risk of death was in the first 6 days of life. An analysis of 102,493 infants <1500 g birth weight identified in the National Inpatient Sample Database found that 35% of the mortality occurred in the first day of life and 58% in the first 3 days of life [8].

Our study is consistent with these prior findings: survival to hospital discharge increased significantly in the first 7 days from 85% to 92%. We did note a continued increase in survival up to DOL 30 (98%), after which survival plateaued before starting to decline. This finding is consistent with the National Inpatient Sample study, where 90% of all mortalities occurred in the first 28 days, but differs from the Canadian study, where relatively few deaths occurred after DOL 7 [8,13]. We can only speculate about the reasons for this difference, which may be due to different maternal and infant characteristics at Canadian vs. U.S. NICUs that affect survival probability, or may be related to study characteristics. Indeed, the Canadian study had a much smaller sample size than both our study and the National Inpatient Sample study, and while infants discharged were appropriately censored in the actuarial survival curves, it is unclear how many infants remained hospitalized after DOL 7, and thus what power the Canadian study had to detect a survival difference at a later PNA. Regardless of the reason for this different finding, we believe it to be particularly important. Studies of survival prediction models and therapeutic interventions focus on times of highest mortality risk [13]. Our results and others suggest that such studies should continue after the first 7 days of life.

Given the high mortality of premature infants, prediction estimates of hospital survival are essential. Clinicians frequently rely on experience and intuition to make such predictions [14]. Intuition-based predictions are often inaccurate: In a study of 268 premature infants, 67% of those predicted by at least one medical provider to die actually survived to hospital discharge [15]. Given the inaccuracy of intuition-based survival predictions, several studies have attempted to develop data-driven prediction models [3,6,7,16]. These models initially relied solely on GA and were used as a guide to initiate or withhold life-saving therapies in the delivery room [17–19]. Recognizing the limitations of risk predictions based solely on GA, the NRN conducted a prospective study of survival to NICU discharge in 4446 infants 22 to 25 weeks’ GA [3]. This study yielded a risk prediction model based on five variables obtained at birth: GA, birth weight, sex, exposure to prenatal steroids, and single or multiple gestation. This model remains easily accessible to neonatologists in the form of an online risk calculator to predict the probability of survival to NICU discharge based on infant characteristics at birth [4]. Recognizing that throughout an infant’s hospitalization, prognosis may change as a consequence of disease progression, therapeutic interventions, complications, and other factors, other studies have aimed at including PNA in risk prediction estimates [5]. Inclusion of 5-minute Apgar score, a likely reflection of an infant’s response to initial therapeutic interventions, improved mortality predictions in over 5000 infants ≤1000 g birth weight treated at NRN centers from 1998 to 2003 [6]. More recently, data from the same cohort of infants updated through 2005 were used to develop risk prediction models for death and neurodevelopmental impairment at specific times during hospitalization [7]. Using stepwise variable selection, separate models were developed for the time of birth, 7 days of age, 28 days of age, and 36 weeks’ PMA, and the authors developed the concept of “outcomes trajectories” by graphically representing the change in predicted survival over time for infants with and without complications. Several other risk prediction tools including scoring systems such as the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology, neural networks, and classification tree analysis have been developed to predict infant survival [6,15,16]. As statistical methods have become more complex, however, some authors have begun to question their practicability in the clinical setting [6].

Our findings support the importance of revising survival predictions based on PNA. The key finding from our analysis is the importance of GA and PNA, and their complex relationship. Although lower GA infants are at higher risk of mortality compared to higher GA infants, the difference decreases with increasing PNA. When infants reach a PMA near term, GA is no longer significantly associated with mortality. The observation that an infant’s probability of survival is highest when reaching a PMA near term is intuitively plausible, but has to our knowledge not been clearly demonstrated in prior studies. As infants remain hospitalized past 37–40 weeks’ PMA, their mortality begins to increase. This is likely because only the medically most complex infants with a higher risk of mortality remain hospitalized past 40 weeks’ PMA. This inference is supported by the fact that of the infants who died after 40 weeks’ PMA, 98% had chronic lung disease, 30% necrotizing enterocolitis, and 20% intraventricular hemorrhage grade III or IV.

The strengths of our study include its sample size and diversity of NICUs represented, the length of time covered in the study, and the availability of daily clinical data in the Pediatrix Clinical Data Warehouse. We were able to control for infant factors on a daily basis and followed infants throughout their entire hospitalization. Our findings are representative of a large proportion of NICUs in the United States and may suffer from less referral bias compared to studies limited to large academic centers. Our study is primarily limited by the fact that the data source is based on a shared electronic medical record and has not undergone the development and scrutiny of a prospective study database. For example, we were not able to identify cause of death. Although all infants included in this study were admitted to a NICU, we are unable to definitively differentiate infants who died after maximal medical interventions from those who may have received palliative care. Our study also does not provide any information about infants who were not admitted to a NICU due to extreme prematurity or other indications for immediate palliative care. Lastly, data on mortality are not available for a subset of infants transferred to a NICU outside of the Pediatrix network. Lack of long-term survival data may partially explain why the highest survival was seen at 37 weeks’ GA due to censoring based on the average length of hospital stay in this population.

In conclusion, we found an overall survival rate of 85%, which increased over the years covered by our study. Survival was higher in more mature infants and increased with PNA. Infants reached a peak in survival around a PMA near term. Our findings illustrate the importance of frequent reevaluation of survival predictions over time and provide important information for providers and parents.

Highlights.

-

-

Overall survival among 64,896 infants <30 weeks gestational age was 85%.

-

-

Odds of survival increased over time, from 80% in 1997 to 88% in 2013.

-

-

Survival increased with postnatal age until a postmenstrual age near term.

-

-

Prematurity is no longer a risk factor in infants with postmenstrual age near term.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Hornik receives salary support for research from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (UL1TR001117). Dr. Cotten receives salary support from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS-1R18AE000028-01). Dr. Laughon receives support from the U.S. government for his work in pediatric and neonatal clinical pharmacology (HHSN267200700051C, PI: Benjamin, under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act) and from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (5K23HD068497-01). Dr. Smith receives salary support for research from the NIH and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (UL1TR001117), the NICHD (HHSN275201000003I and 1R01-HD081044-01), and the Food and Drug Administration (1R18-FD005292-01).

Role of the Funding Sources: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- DOL

Day of life

- ELBW

Extremely low birth weight

- FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- GA

Gestational age

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- NRN

Neonatal Research Network

- PNA

Postnatal age

- SGA

Small for gestational age

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions:

Drs Hornik and Smith had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Hornik, Cotten, Laughon, Smith

Data acquisition: Clark, Hornik, Smith

Drafting of the manuscript: Hornik, Sherwood, Smith

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cotten, Laughon, Clark

Statistical analysis: Hornik, Sherwood, Smith

Approval of the final manuscript as submitted and agreement of accountability: All authors.

Dr Hornik wrote the first draft of the manuscript (no honorarium/grant/specific payment received).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alleman BW, Bell EF, Li L, Dagle JM, Smith PB, Ambalavanan N, et al. Individual and center-level factors affecting mortality among extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e175–e184. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Lewit EM, Rogowski J, Shiono PH. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with variation in 28-day mortality rates for very low birth weight infants. Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics. 1997;99:149–156. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins RD. Intensive care for extreme prematurity-- moving beyond gestational age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1672–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. [Accessed 01/16/2015];NICHD Neonatal Research Network (NRN): Extremely Preterm Birth Outcome Data. 2012 http://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx?start=19:49:16.

- 5.Meadow W, Reimshisel T, Lantos J. Birth weight-specific mortality for extremely low birth weight infants vanishes by four days of life: epidemiology and ethics in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1996;97:636–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, Bobashev G, Mathias E, Liu B, Poole K, et al. Prediction of death for extremely low birth weight neonates. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1367–1373. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, Tyson JE, Langer JC, Walsh MC, Parikh NA, et al. Outcome trajectories in extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e115–e125. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed MA, Nada A, Aly H. Day-by-day postnatal survival in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e360–e366. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spitzer AR, Ellsbury DL, Handler D, Clark RH. The Pediatrix BabySteps Data Warehouse and the Pediatrix QualitySteps improvement project system--tools for "meaningful use" in continuous quality improvement. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:49–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e214–e224. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Soll RF, Morrow KA, et al. Mortality and neonatal morbidity among infants 501 to 1500 grams from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1019–1026. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meadow W, Frain L, Ren Y, Lee G, Soneji S, Lantos J. Serial assessment of mortality in the neonatal intensive care unit by algorithm and intuition: certainty, uncertainty, and informed consent. Pediatrics. 2002;109:878–886. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones HP, Karuri S, Cronin CM, Ohlsson A, Peliowski A, Synnes A, et al. Actuarial survival of a large Canadian cohort of preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens SM, Richardson DK, Gray JE, Goldmann DA, McCormick MC. Estimating neonatal mortality risk: an analysis of clinicians' judgments. Pediatrics. 1994;93:945–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meadow W, Lagatta J, Andrews B, Caldarelli L, Keiser A, Laporte J, et al. Just, in time: ethical implications of serial predictions of death and morbidity for ventilated premature infants. Pediatrics. 2008;121:732–740. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambalavanan N, Baibergenova A, Carlo WA, Saigal S, Schmidt B, Thorpe KE. Early prediction of poor outcome in extremely low birth weight infants by classification tree analysis. J Pediatr. 2006;148:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz JM, Paneth N. Treatment decisions for the extremely premature infant. J Pediatr. 2000;137:593–595. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.110532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partridge JC, Freeman H, Weiss E, Martinez AM. Delivery room resuscitation decisions for extremely low birthweight infants in California. J Perinatol. 2001;21:27–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peerzada JM, Richardson DK, Burns JP. Delivery room decision-making at the threshold of viability. J Pediatr. 2004;145:492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]