Each year in the United States, hundreds of thousands of teenaged women bear children (Martin, Hamilton, Osteman, Curtin, & Mathews, 2015). Teen pregnancies often result in suboptimal social and behavioral outcomes for both mother and child including later entry into prenatal care, higher rates of pre-term births and infants born at low birth weight, lower rates of breastfeeding, higher rates of infant mortality and rapid subsequent pregnancies, and greater likelihood of incomplete schooling (Holcombe, Petersen, & Manlove, 2009; Terry-Humen, Manlove, & Moore, 2005). Pregnant adolescents face challenges of the transition to parenthood (Belsky, 1984) while undergoing extensive physical, social, neurological, and cognitive developmental changes (Moriarty Daley, Sadler, & Dawn Reynolds, 2013; Sadler & Cowlin, 2003; Whitman, Borkowski, Keogh, & Weed, 2001). Adolescent pregnancy and parenting can also be stressful for the pregnant couple and their families. Factors that contribute to these stresses are the unintended nature of most adolescent pregnancies (Stevens-Simon, Beach, & Klerman, 2001) and the social-ecological contexts of poverty, racism, poor education and violence in which many pregnant teens live (CDC, 2007; Coyne & D’Onofrio, 2012; Ford & Browning, 2011; Ford & Rechel, 2012).

The many stresses of adolescent parenting influence teens’ capacity to become sensitive parents (Whitman et al., 2001). One of the capacities thought to underlie sensitivity is the parent’s ability to reflect on both her own and the baby’s thoughts and feelings, to try to make sense of her own and the baby’s behaviors in light of mental states (thoughts, feelings, intentions). This capacity in parents, known as reflective functioning (Sadler, Slade, & Mayes, 2006; Slade, 2005), has been linked with sensitive parenting (Grienenberger, Kelly, & Slade, 2005) and the development of secure infant attachment (Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005) in adult mothers. Reflective parents are curious about their own and their children’s mental states and try to understand and respond to children’s feelings, thoughts, and intentions, rather than solely responding to the children’s overt behaviors (Slade, 2005). For example, a reflective mother would be curious about and open to the reasons for her child’s distress, as opposed to simply trying to control his crying. The capacity to envision mental states in the self and other is thought to emerge slowly over the course of development, likely not emerging fully until adulthood (Borelli, Compare, Snavely, & Decio, 2014; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., 2005).

Impending parenthood requires a particular kind of reflection, as the mother-to-be must begin to imagine her child as well as herself as a parent (Slade, 2005, 2007). These are crucial aspects of the transition to parenthood, as the child becomes more real to the mother, who begins to develop a relationship with and an attachment to the fetus, and a sense of herself as a mother and protector. Adolescence, a time of great biological, hormonal, cognitive, and psychological reorganization, is particularly challenging, as teens develop their initial capacity to reflect. This is true even for the most supported and low risk women (Slade, Cohen, Sadler, & Miller, 2009), but is intensified for mothers struggling with adverse circumstances such as poverty, familial disruptions, community violence, and other toxic stressors (Whitman et al., 2001).

While the development of parental reflective capacities has been described in parenting teens (Demers, Bernier, Tarabulsy, & Provost, 2010; Mayers, 2005; Mayers, Hager-Budny, & Buckner, 2008; Slade, Sadler, et al., 2005), to our knowledge, RF has not been studied in pregnant adolescents, which led us to conduct the current study. In this paper, we examine pregnant teens’ descriptions of their emotional experience of pregnancy and their thoughts about the unborn child and impending parenthood. In particular, we were interested in how the capacity to reflect (or, conversely the relative inability to reflect) in a sample of pregnant teens with relatively low levels of RF, influenced their experience of pregnancy.

Primary Study: Minding the Baby®

The primary study, which provided the context and the data for this secondary analysis, is a randomized controlled trial of an intensive home visitation program, Minding the Baby® (MTB). Minding the Baby® is designed to provide young first time parents ages 14–25 living in distressed community environments with an array of relationship-based services aimed at improving health, mental health, life course, and parent-child relationship outcomes. In the primary study we enrolled volunteer participants from two urban community health centers into control (usual care) and intervention groups. The intervention, guided by a reflective parenting approach, consisted of weekly and then bi-weekly home visits from a nurse and social worker team of home visitors through 24 months after the babies were born. Home visits focused on maternal and infant health, mental health, life course outcomes, case-management, and healthy parent-child relationships. For a fuller description of the program and preliminary outcomes, see (Ordway et al., 2014; Sadler et al., 2013; Sadler et al., 2006).

In the primary study we noted that the baseline levels of RF (during pregnancy and before any intervention had begun) were quite low (mean=3.1, s.d.=0.8 on a scale of 1–9) among adolescent participants (Sadler et al., 2013). Given the complex developmental and social contexts for adolescent pregnancy, we wondered how the experience of pregnancy was affected by the relative absence of RF. In this qualitative study, we explored whether teens’ responses to the open-ended questions in the Pregnancy Interview would provide additional insight into these issues or into their reflective capacities. Specific aims of the study were to: 1) describe the dominant themes in the narratives of a racially and ethnically diverse sample of pregnant adolescents, and 2) describe how the teens’ capacities to reflect on the self, family members, partners and infants were related to their ability to anticipate how they will navigate the tasks of adolescent parenthood.

Methods

Qualitative Study Design: Interpretive Description

Interpretive description is a qualitative approach in which researchers use inductive methods to explore clinical phenomena from subjective perspectives, and to generate conceptual linkages to inform clinical practice (Thorne, 2008; Thorne, Kirkham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2004). This approach helped us to grasp the complexities of RF in pregnant teens, and to set the stage for promoting the care and counseling of teen mothers in developing their reflective capacities as new parents. This was a secondary qualitative analysis of interview data collected as part of the larger primary Minding the Baby® clinical trial.

Sample and Setting

Primiparous English-speaking women age 14–25 at low medical risk (no active substance abuse, serious medical conditions, or active psychosis) enrolled in prenatal care at two urban neighborhood health care centers were invited to participate in the study when they were in the latter part of the second trimester of their pregnancies. Participants over age 18 provided consent, and parental permission/participant assent was obtained for teens less than 18 years of age. There were 105 women enrolled in the primary study and for this analysis; a subsample of 30 transcripts were purposively selected for maternal age 14–19 years and with a range of RF levels. The study was reviewed and approved by the university and community agency human subject research review boards.

Data Collection and Interview Schedule

Data consisted of participant responses to the Pregnancy Interview, a 22 item semi-structured interview designed to explore a woman’s emotional experience of pregnancy and her developing relationship with her baby during the last trimester of pregnancy (Slade, 2003; Slade, Patterson, & Miller, 2007). Interviews were conducted by female clinical social workers specifically trained in administering the interview. All interviews were conducted and audiotaped in either in the participant’s home or in a private office at the community health center before the home visiting intervention had begun. Recorded interviews were transcribed and then were checked for accuracy by the interviewer.

Pregnancy Interviews provide descriptions of pregnant women’s thoughts, feelings and intentions about pregnancy, developing mother-infant relationships, and early views of emerging maternal roles (Slade, 2003). Open-ended questions are posed to the pregnant woman with probes to help facilitate her responses, such as: “Can you remember the moment you found out that you were pregnant? Tell me about that moment”; “Since you’ve been pregnant, what has your relationship with your mother been like?” “Describe when the baby first started to feel real to you”; “What do you try to give the baby now…. What will your baby need from you after it is born?” (Slade, 2003, pp. 1–2). The Pregnancy Interview has been used in samples of adult women and has been shown to predict adult attachment classification (Slade, Director, Grunebaum, Huganir, & Reeves, 1991). A coding system was developed for RF, tested, and shown to be linked with child attachment and parental behavior outcomes (Levy, Truman, & Mayes, 2001; Slade, Belsky, Aber, & Phelps, 1999; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., 2005). The RF scale ranges from 1–9, with higher scores denoting higher levels of reflectiveness. Coders, blinded to the group status of participants, were trained on the RF coding system and demonstrated 80% inter-rater agreement on RF scores (Sadler, et al., 2013).

An RF score of 1 or 2 indicates that the mother focuses primarily on behavior, or physical reality, and that she denies or blocks her own or another’s mental states. There are only the most veiled references to the imagined child as having a mind of its own. A score of 3 indicates that mothers have some awareness of their own and others’ thoughts and feelings, and can begin to see the imagined child’s subjective experience. A score of 4–6 indicates that the mother is able to reflect upon thoughts and feelings in herself and in her imagined child and that she can appreciate the inter-subjective nature of mental states. A score of 7 or above indicates marked to exceptional levels of RF (Slade et al., 2007).

Study levels of pregnancy RF ranged from 2–5 (5 was the highest level of RF coded in the adolescent sub-sample from the primary study). Although we purposely chose a sample of women with a range of RF levels, 84% of the interviews had scores in the non-reflective range (1–3); while only 4 participants had RF levels of 4 and one participant had a level of 5. Thus, for the most part, our data offer a glimpse of what pregnancy is like for teens who have not yet developed the capacity to reason about and make sense of their own or others’ internal experience.

Analysis

For the current analysis, all interview transcripts were entered into the Atlas.ti qualitative data management program, and were read through by all members of the research team. The team (all experienced qualitative researchers) included two pediatric nurse practitioners with extensive experience caring for pregnant and parenting adolescents and a nurse-midwife with extensive experience providing prenatal care to underserved women. An audit trail documented analytic steps and how the team reached consensus on coding and development of themes (Rogers & Cowles, 1993).

Researchers were blinded to the previously determined RF levels for each transcript, until after the qualitative coding and thematic analysis was completed. The team began the analysis with a “start list” of codes based on the attributes of RF and the conceptual areas reflected in the interview questions, and as interview transcripts were read and re-read, inductive codes were added (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The final coding structure included 52 codes. Each team member coded the first 10 interviews to achieve 90% or better agreement on the coding structure and the coding of the data. Once agreement was achieved, the remainder of the interviews were coded. This process was repeated for the clustering of codes into themes and the development of participant profiles.

Using thematic analysis, the research team clustered codes and quotes into patterns and, finally, into five themes that described the ways in which participants saw their pregnancies, their babies in utero, their support systems, and their thoughts about becoming parents—all of which contributed to their capacity for RF (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Thorne et al., 2004). When there was disagreement among research team members in developing themes or in the interpretation of data, discussion was conducted until consensus was achieved.

After coding, data were displayed using grids for comparison across participants’ RF levels, developmental and demographic characteristics, descriptive sub-themes and quotes to relate pregnant teens’ experiences of pregnancy with RF capacities (Ayers, Kavanaugh, & Knafl, 2003). We then returned to the interview data to construct participant profiles for each participant, which included demographic information and brief narrative material for each theme. Extreme cases illustrating very low and relatively high levels of RF were constructed and examined to further explicate the themes and their meanings (Ayers et al., 2003).

Findings

The 30 participants were all 30–39 weeks gestational age at the time of the interviews. Participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Pregnant Adolescents (n=30)

| Characteristic | Mean (s.d.) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 17.7 (1.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 27% | |

| Latina (Puerto Rican & Mexican American) | 73% | |

| Highest grade in school | 10.4 (2.4) | |

| RF level- previously coded from PIs | 3 (0.7) range= 2–5 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 10% | |

| Single with partner contact | 65% | |

| No contact with partner | 25% | |

| Adolescent lives with | ||

| Mother | 47% | |

| Both Parents | 7% | |

| Homeless | 7% | |

| Husband/boyfriend | 20% | |

| Other family members | 2% | |

| Self | 3% |

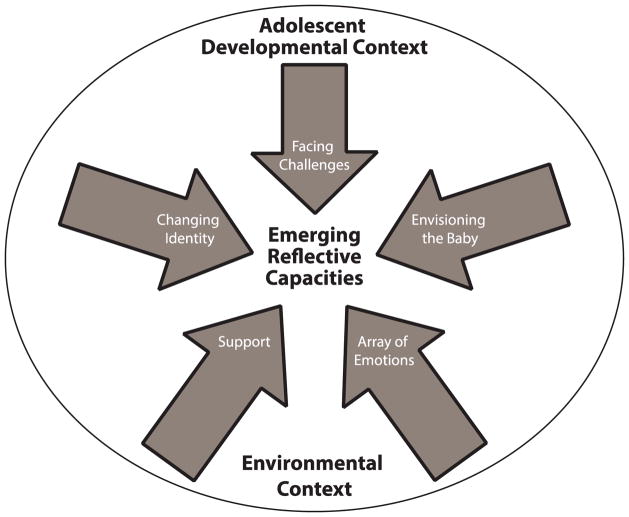

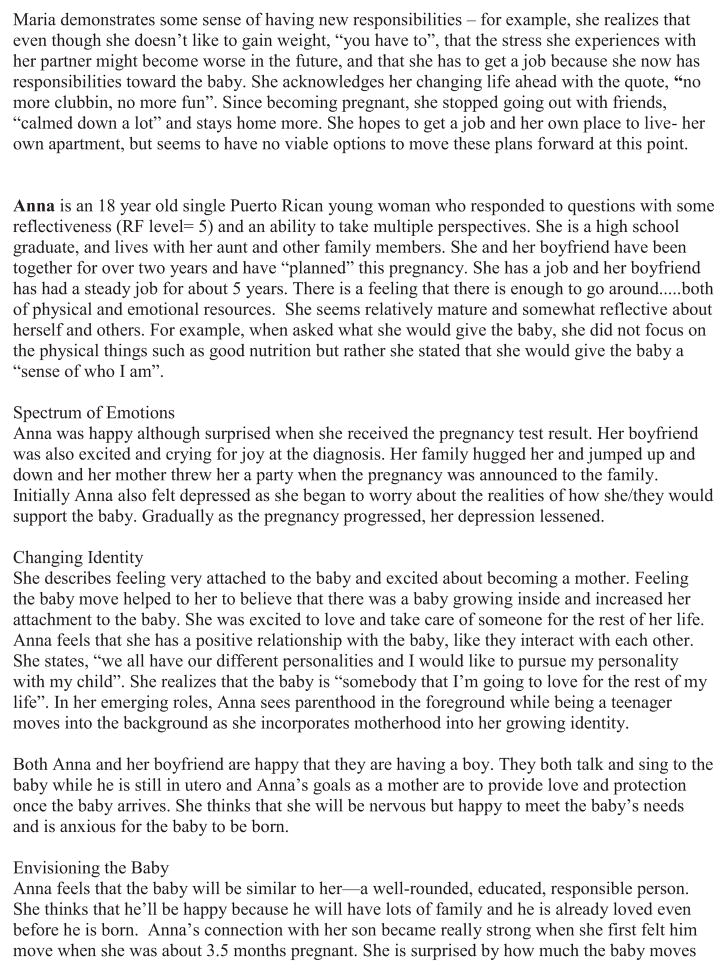

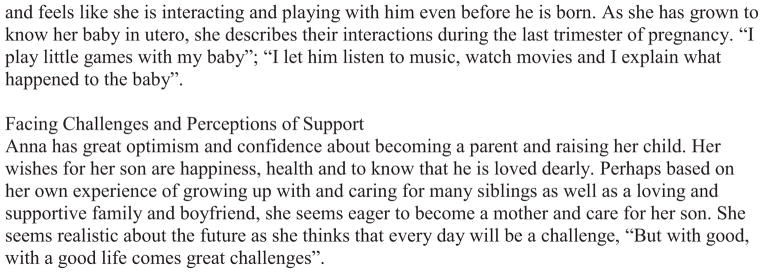

We identified five themes that create a picture of how the participants reflected upon their pregnancies, their unborn babies, their emerging parental roles, and their relationships with family members and partners. The themes were: Spectrum of Emotions, Envisioning the Baby, Changing Identity, Facing Challenges, and Perceptions of Support. Throughout these themes, teens demonstrated their varied and often limited capacities for parental reflectiveness shaped by their adolescent developmental characteristics and the complex and their changing social and environmental contexts (see Figure 1). We also present two extreme case profiles as exemplars of participants’ varied personal narratives and capacities for RF (Figure 2); one participant (Maria) demonstrated very low levels of reflectiveness, whereas (Anna) had a higher level of RF. Maria’s level of RF was more typical of our sample, whereas Anna’s higher RF represented a marked contrast with the majority of participants.

Figure 1.

Themes Depicting Emerging Reflective Capacities

Figure 2.

Exemplar Cases

Spectrum of Emotions: “I was everywhere”

Pregnant teens experienced a range of emotions—from ecstasy to despair—sometimes holding widely conflicting feelings at once. The initial pregnancy diagnosis, often a complete surprise, was a particularly emotional moment. Those with greater capacity to reflect, were able to regulate and make sense of their complex emotions. For those with limited reflective capacities, however, it was an overwhelming moment. The young women often were “shocked” or “stunned” on receiving their initial pregnancy diagnosis and recalled feeling paralyzed or struggling to process their thoughts and feelings. One participant with very low RF described her confusion and inability to process her emotions.

I didn’t believe it, I was like, no are you sure, are you positive? I couldn’t believe it, I got like a heat flash, I didn’t know. I ran to the phone and I’m like stuck, like, I didn’t know who to call first. I know—I’ll wait to get home to tell my mother and tell my baby father.

Some participants had initially contemplated pregnancy termination. One teen who had arranged for an abortion “walked out at the last minute”; others were deterred by logistical or financial barriers, or a family member’s disapproval. On the other hand, a number of teens reported having been thrilled, or “ecstatic” at their diagnosis; most of these women stated that they had planned their pregnancies, or had “always wanted a baby.”

The prospect of disclosing their pregnancies was sometimes daunting. Teens were “nervous,” fearing that a parent might “disown,” “never forgive,” or even “report” them to government authorities (such as child protective services). The young women were especially concerned about disappointing or angering their mothers, although one teen worried that this distressing news would “break my grandmother’s heart.” Many family members, however, although shocked, were accepting right from the start. When this occurred, it was a profound relief. One teen described a particularly heartening albeit not reflective description of her family’s reaction:

My mom and my aunt were like, what happened, what happened, I want to know! And I was like, well, you know, I’m having a baby. And they started hugging me and jumping around and everything. My mom was like, OK we have to have a party now, and so they baked me a cake and everything.

The teens also worried about disclosing the news to their babies’ fathers, who were often completely shocked. Incredulity was sometimes followed by insistence on repeat pregnancy tests or questions about paternity, as this teen explained, “He asked me: who was the baby’s father? I wanted to kill him, basically. Because it hurt, because I was living with him, and it just really hurt.”

Some teens were particularly pleased to be “giving him his first child;” however, several of the young men had fathered other children. After recovering from the shock of the initial diagnosis, most teens came to accept their situations. Nevertheless, a minority of participants became increasingly unhappy or uncertain about facing the myriad challenges of motherhood. One of these women was homeless, and another just sounded sad and lonely, saying “I don’t have nobody to talk to, so I just stay here. It’s bad. I just look at the clock and let the hours go by, until the next day. I can’t really do nothing.” Whether teens had come to feel, on balance, more or less positively about becoming mothers, most described some emotional volatility that persisted throughout pregnancy.

Envisioning the Baby: “I Feel Like We Have a Connection”

The teens described the different ways in which they began to envision their unborn infants and to develop relationships with them. They expressed hopes for their children as they envisioned them growing up. Since this process involved abstract thinking and the ability to project into the future, the teens—who were at different developmental stages and different levels of reflective functioning—varied greatly in their ability to express themselves and to consider these future possibilities.

For most teens, envisioning their babies often began when they first felt fetal movement, or when they first heard the fetal heartbeat or saw an ultrasound image of the baby. Some teens stated that they had known right away (as early as the positive pregnancy test) that they were pregnant and had started picturing their babies from that moment on. However, for most teens, the sense of connection developed gradually although some young women still found it difficult to imagine the baby well into the third trimester. This young woman explained: “Like I got a baby growing inside me, my body’s making a baby. I don’t know, that’s weird for me.”

Learning the gender often helped the baby seem more real. Many teens imagined relating to the baby based on their views of gender roles, including plans for dressing and playing with the baby. One teen said, “I wanted it to be ponytailed and dress her up real nice, and with boys you can’t be ponytailed,” while another teen described, “I’m better off having a girl. I can play with her, get Barbies.” Sometimes the teens seemed to envision their babies as little versions of themselves, with traits similar to their own -- such as being good dancers, stubborn, tall, or friendly. This image of the baby as a miniature self sometimes enabled them to anticipate the challenges of parenting someone like themselves. “I get scared sometimes cause I don’t really wanna have to go through the same thing my Mom went through with me…” One teen noted that boys are easier to raise, and girls are “harder to handle and have mood swings.” All of these examples are indicators of really absent RF.

Many teens’ attitudes and behaviors suggested magical thinking about their relationship with the babies, or a magical ability to communicate directly with the baby through the abdominal wall. One teen illustrated a very low level of RF with the following quote, focusing mainly on behaviors rather than emotions.

I can feel when he is tired and stuff, like when I have been walking a long time, you know, when he is tired so I go home and lay down. When he is thirsty I drink water. When he got to go to the bathroom I pee. I feel like we have a connection.

Some teens also attributed intentions or motivations to their unborn infants. For example, this teen seemed to think her unborn baby experienced jealousy, “…like when I be holding other babies, or doing kisses, he’ll know. Like he’ll start kicking when there are other babies around.” Magical descriptions such as these were more prevalent in interviews in which the teen also manifested other examples of concrete thinking.

Many adolescents reported that they demonstrated love for their babies by touching their bellies, reading to and playing music for the babies, and planning to breastfeed. “I talk to him every morning to show him love, cause if I don’t express nothing towards him, then he’ just growing inside of me without no feelings.”

In responding to questions about future worries about their infants, teens’ worries ranged from none to a host of concerns about their health and the impending birth. However, many teens anticipated the future, worrying about whether they would be good students and hoping they would complete high school. Some teens expressed worries about their boys being “out on the street” and hanging out with “bad people.” In these cases, the visions of their children were blended with hopes that their children would not be harmed, that they simply would be alive. The teens realized that their children would most likely be raised in neighborhoods that were often dangerous. Several teens expressed the hope that their daughters would not get pregnant “at an early age,” and would “be wiser” than their mothers.

Changing Identity: “Oh, My; Having a Baby Changes Everything”

Identity formation is a fundamental developmental task in which adolescents typically explore potential life roles in an effort to construct their adult identities. The participants discussed their changing identities in terms of their physical appearances, lifestyle changes, and how they had begun to think of themselves as teens and as mothers.

Although many teens were unhappy with their appearance, with having to gain weight, or with common pregnancy-related discomforts, some were proud of their bellies and enjoyed the new status associated with being pregnant. Lifestyle and identity changes also entailed loss of freedom. They noted the sports and social events they would have to give up as mothers, and talked about not being able to “hang out with friends” or go biking or rollerblading. Several young women recognized the magnitude of the life changes they were facing. One teen stated, “I was the type of person, I used to like to hang out in the street…I’m like, oh my; having a baby changes everything.”

For some adolescents, pregnancy motivated positive change. One teen stated, “[I] was too much on the streets. [Pregnancy is] teaching me a lesson. [It] may be a lifesaver.” Another echoed this sentiment, “It’s better for me anyways because I was always getting into a lot of trouble.”

Having an incentive to change and an understanding that they might not be able to do the things that other teenagers do triggered a shift from being more self-centered to more child-focused. One mother noted that she was used to being cared for by her family, but soon would be caring for her child. Another adolescent said, “At first I was like, I’m just going to do what I have to do. But now, it’s like I want to do it because I want to raise my baby the best way that I can.” A few teens saw that having a baby would enhance their own sense of maturity, and the feeling that they were important and needed by the baby. “It will feel good. It will show people that I can do it. That I don’t need nobody to raise my child.”

Facing Challenges: “Just Do It”

Becoming a parent was viewed by most teens as not only a role shift, but as a significant challenge. Teens’ sense of what parenting meant ranged from performing specific tasks to being responsible for another’s well-being. While some teens worried about meeting these challenges, others conveyed confidence, and even a sense of adventure. This theme describes how the teens viewed the myriad challenges ahead.

When asked what they would do for the baby after birth, many teens described specific infant care activities. Some teens, however, thought beyond concrete behaviors and described a broader set of challenges, such as balancing school or work with child care, finding new sleeping arrangements, having enough money to provide for the baby, and tolerating sleep deprivation. Several teens commented that they would need to provide “love, attention, “and to “be there” for the baby, an experience that they had not necessarily had themselves as children. One teen described parenting as, “just giving him what my parents could have given me.” For several teens, “being there” also meant being emotionally involved and supportive, and providing moral guidance so they would become decent persons, and these teens struggled to articulate more complex, abstract and reflective visions of parenting. One adolescent explained: “He has to learn responsibilities. All that good stuff. And I will have to teach him his feelings, how to feel about certain things.” This young woman may have meant that she would help him figure out his feelings, which is a more reflective comment.

Several teens tried to express their sense of the breadth of the burden that they would have to shoulder. One young woman noted that she would have to make decisions for someone else and another felt she needed to “walk him through life.” In one of the more reflective comments, this teen struggled to articulate her conception of what it meant to be, and to care for, a helpless newborn:

When they come out, it’s like a new world for them. It’s like, if I were going to go move to another country, like China or something, it’s gonna be new for me, so when she comes out this is a new world for her, so I wanna be there for her, I wanna teach her things.

Regardless of whether the challenges were viewed concretely or more globally, the young mothers experienced a range of emotions, sometimes simultaneously. Some teens, were confident that they were “mature enough,” and knew what parenting entailed. This was often based on prior experience caring for younger family members. One teen explained, in an example of a particularly non-reflective comment, that parenting would be easy because if you have “a great babysitter to take care of your child, you can do anything you want.” Other young women were confident that since they had certain traits—such as knowing “right from wrong” or behaviors—such as not smoking or drinking they’d be good mothers. In contrast to these less reflective comments, one young woman expressed her doubts clearly and thoughtfully: “I wasn’t ready to be a mom. No one’s ever ready to be a parent—especially at 17.”

A subset of participants viewed parenting as an adventure, anticipated this new role with excitement and began to realize the emotional complexity inherent in becoming a parent. Some teens were just eager to have labor over and to meet the baby, while for other teens becoming pregnant had prompted a new sense of who they might become, or enhanced their self-confidence. One teen, who was more reflective, saw the emotional complexity of her situation; she wanted to finish school and prove that she could still do well in life. She explained, “I want to bring her my high school diploma and say ‘look Ma, I did it even though I got off track a little bit’. And my dad too.”

When asked how they would meet the challenges of parenting, many of the young women responded that they would just “do it.” Their plans often had little detail other than the expectation that their own families (and sometimes the baby’s father’s family) would provide financial help and child care. Expectations of the baby’s father were less consistent; although some felt they could count on the baby’s father for help, other young women did not, as this woman explained, “I don’t care if he says he’s not the father. I don’t care. You know, if I have to raise him by myself, I am going to die trying.”

Perceptions of Support: “My Mom Will Always Be There”

Most of the adolescents realized that they needed social support to face the challenges of pregnancy and motherhood. The majority of participants lived with their mothers, and their fathers were described as being only intermittently present. Twenty per cent of the teens lived with their partners; however, teens often described markedly changed couple relationships as their pregnancies had progressed through three trimesters. In this theme we describe perceptions of their support networks and what the teens expected from family members and the babies’ fathers.

Some family members were initially described by the teens as being disappointed or angry. One teen explained: “They were like, ‘No you shouldn’t have a baby because you’re not going to have a good life. You’re not going to, like, be a teenager. You’re going to be a mother’.”

In some cases, adolescents’ relationships with family members improved over the course of pregnancy. One teen who was somewhat reflective in speaking of her mother said, “I can relate to her in a lot of ways. I open up to her more.” As the family came to accept the pregnancy, they provided tangible and emotional support to the pregnant adolescents.

When asked to compare how they might raise their children with how they themselves were raised, teens spoke in less reflective ways and primarily about their mothers. Those who saw their mothers as good mothers wanted to have a similar parenting style. “It’s just how she raised us. To be loveful, you know. Even if I don’t do something right, I know she got me. I know she’s my backbone.” Others, however, wanted to parent differently from the way their parents had raised them. One teen demonstrated her behavioral rather than reflective stance when she said: “I won’t beat my kids. I’m never going to beat my kids, not to the point of belts, sticks and hangers and all that. No, that’s one of the ways I won’t be like my father.” Several adolescents expressed a feeling of abandonment by their own parents, and were resolved to be there for their children. One teen and her baby’s father had both experienced abandonment by a parent. Her response illustrates a slightly more reflective stance as she uses the word “want,” explicitly identifying a feeling state.

I want him to be there because my father wasn’t there for me. And his mother wasn’t there for him. I don’t want my child to go through what he went through and what I went through. You know, I want us to be together like a family, like we planned to be.

Many teens were expected tangible and emotional support from family members, but were less sure about what to expect from their babies’ fathers. “I am not sure how long I am going to be with my boyfriend. But I know my Mom will always be there, my sister, my brother, my father.” Several fathers-to-be who had been pleased in the beginning of the pregnancy, developed more negative feelings as the birth approached—almost the reverse of the patterns observed with their mothers. One teen described her partner’s reactions to the pregnancy in highly reflective comments as she thinks about changes in emotions over time:

Initially: “He ran, he hugged me, gave me a kiss on the cheek. He was happy too ‘cause he wanted another baby.”

Later: “My baby’s father and I used to argue and I used to cry. He used to be like, ‘you got fat, I’m not gonna be with you.’ …When we broke up, it was like he didn’t care. It wasn’t what I expected. He just went with the next one—like nothing happened.”

The young women often were not surprised when their boyfriends left them during pregnancy; it seemed almost expected. One teen explained, “I heard that guys do that anyway.”

Some adolescents hoped that their babies’ fathers would be involved in the babies’ lives—whether or not they remained a couple and whether or not the fathers provided financial support. Other times, the teens conveyed a sense that not having the baby’s father around might be for the best.

He is not really in the picture, like he got two other girls pregnant too. So it’s like, you know, sometimes he goes ‘that’s my kid’ and sometimes he goes he starts cursing ‘It’s not my kid, no’ and all that stuff. So I would rather not have him around because he’s like too much involvement in bad things. He just got locked up today.

Discussion

The words of these adolescents provided a rich glimpse into their emotional experiences of pregnancy and insight regarding their limited efforts to reflect on this enormous and compelling developmental shift. Their stories demonstrated that pregnancy experiences were intricately intertwined with developmental characteristics and the often-difficult relational and environmental contexts of their daily lives. Those who were more reflective could embrace the emotional complexity of this moment, could imagine the baby and their relationship, could begin to imagine themselves as parents in an increasingly nuanced way, describe the real challenges of impending parenthood and assess who would support them. Less reflective teens were more emotionally overwhelmed, more focused on the concrete changes of pregnancy, had a clichéd view of parenthood and its challenges, and were unable to imagine the kind of support they would need and whether support would be available.

The developmental characteristics and challenging social contexts of these teens represented a double threat to their capacity to assume a reflective stance in considering their thoughts related to the pregnancy, the baby, and parenting. The interview questions asked the adolescents to stretch their thinking in ways that might have been new or difficult—either because of their stage of cognitive development or because they may have been living in social/family environments where feelings were not overtly discussed.

The Experience of Pregnancy

Although the five themes found within the interviews revealed patterns consistent with other samples of pregnant teens (Rentschler, 2003; Spear, 2001; Whitman et al., 2001), these data add depth to our understanding of the challenges of adolescent pregnancy. Reisch et al reported that two key factors influence the adolescent experience of pregnancy and parenthood: their unique developmental characteristics, and their social support and stressors. Pregnant and parenting teens are still in the midst of developmental tasks that include emotional and relational changes as well as the cognitive changes of moving from concrete thinking to more abstract adult reasoning (Elkind, 1998; Hamburg, 1998; Moriarty Daley et al., 2013).

Furthermore, although adolescents are typically quite engaged with their own thoughts and perspectives, the ability to be reflective and insightful about how their own thoughts and emotions relate to their behaviors is generally less well-developed (Benbassat & Priel, 2012; Borelli et al., 2014). There are few studies of adolescent RF in the literature, and all of them described relatively low levels on the RF scale: Borelli and colleagues (2012), reported a mean level of 2.95 (1.1) in a low-risk sample of white European adolescent females; Ha and colleagues (Ha, Sharp, Ensink, Fonagy, & Cirino, 2013) reported a mean level of 3.15 (0.2) in teens with mental health diagnoses; and (Benbassat & Priel, 2012) found a mean level of 3.88 (1.1) in their normative sample of Israeli youth.

An illustration of this low reflectiveness occurred when the young women recalled their thoughts and feelings in early pregnancy; almost uniformly, they recalled that they and their partners felt “shocked” at the pregnancy diagnosis. As the pregnancies progressed, however, so did their abilities to imagine how they were going to reconstruct their lives with the reality of a new baby in the near future. For some, especially those who felt supported by family, emotional swings were present but minimal, while for those with varying support from family and partners, they justly felt abandoned, and themes of sadness and loneliness pervaded their stories.

Social support is a crucial factor in the transition to parenthood (Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Whitman et al., 2001). When teens in this study could anticipate tangible help and emotional support they felt more confident about parenting. When family support was absent, however, adolescents had more anxieties about parenting and managing their own lives. The adolescent’s own mother is usually central to the well-being of the young mother and her child (Oberlander, Black, & Starr, 2007; Sadler, Anderson, & Sabatelli, 2001; Sadler & Clemmens, 2004). Future grandmothers often have varying reactions to their daughters’ pregnancies and capacity to be supportive, as seen in these interviews.

Many pregnant teens are ambivalent about their relationships with their partners. These are often immature relationships that do not easily withstand the stresses of approaching parenthood. The young men often experience high levels of poverty, violence, and involvement with crime, which may limit their participation in parenting (Scott, Steward-Streng, Manlove, & Moore, 2012). In addition, multiple competing romantic relationships with other women, and difficult relationships with maternal extended family members all influence the fathers’ participation in the teens’ pregnancies (Bronte-Tinkew, Carrano, Horowitz, & Kinukawa, 2008; Futris & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2007; Miller et al., 2007). Most adolescents in our sample had low expectations of their babies’ fathers regarding emotional support and tangible help. In many cases the teens’ relationships with their partners might be described more accurately as an additional source of stress rather than support. The volatile partner relationships during pregnancy likely foreshadow troubled times ahead for these young couples. Couple conflicts as well as the difficult experiences that many of the young men had with their own parents present major challenges for cooperative co-parenting that was so profoundly hoped for by the young women. The teens’ limited capacity to reflect on these conflicts and to make sense of them, may predict that the conflicts will be acted out repeatedly, rather than the new parents being able to move forward in their new roles and evolving relationship.

Living in under-resourced urban environments has been shown to have both direct and indirect effects on adolescents, related to the limited social networks that are part of their daily lives (Ford & Browning, 2011; Ford & Rechel, 2012). Teens who live in such environments often have witnessed or experienced chronic or complex trauma due to violence, assault or significant losses (Courtois, 2008; Slade & Sadler, 2013). These exposures also reflect the diverse social inequities regularly experienced by many pregnant and parenting teens (SmithBattle, 2012). Childhood and ongoing trauma exposure has been associated with negative emotional or physical health, and may lead to distortions in perception and dysregulated affect, which interfere with the capacity for RF (Courtois, 2008; Slade & Sadler, 2013).

The adolescents in this study lived in challenging social environments, and therefore had much to worry about as they contemplated labor and birth, and the future. Several teens had experienced harsh discipline, parental absence, interrupted schooling, and the unrelenting stresses of living within poverty amidst an often-unsafe urban neighborhood. It was unsettling for many of them to contemplate their own children growing up in a community that they knew to be threatening and dangerous for young people, especially for boys and young men. They wanted a better life for their unborn children, yet many were haunted by their own difficult childhood experiences.

For some teens who had been out on the streets, living away from their family’s home or estranged from family members prior to the pregnancy, the crisis of the pregnancy brought them back home and to their families, at least for a period of time. This notion of a second chance afforded by teen pregnancy serves as a reminder that not all families and teens view teen pregnancy as a universally bad situation (Sadler & Clemmens, 2004; Spear, 2001).

Capacity for Reflective Functioning in Pregnancy

When parents are curious about their children’s thoughts and feelings and try to imagine their feelings or desires, they are more likely to respond to the child in a sensitive and less prescriptive manner (Slade, Grienenberger, et al., 2005). This reciprocal experience enhances the development of a secure infant attachment relationship and allows the parent to model affect regulation and impulse control for young children. In order for RF to be possible, adolescent mothers need to be able to “de-center”, that is to not only see the world from their own perspective and reflect on their own mental states, but to see the world from the perspectives of their infant to be able to reflect upon their infants’ mental states (Slade, 2005).

Some participants could see themselves as mothers, and see the baby as a person with distinct needs and feelings. Others, however, could not envision being a mother or could not see the baby as an individual, but rather focused on tangible aspects of the babies or talked about pregnancy and impending parenthood through the lens of their adolescent world views; they felt that their families would take care of them and their babies, and that they would then be able to go back to the business of being teenagers.

Most interviews had been coded with relatively low levels of RF, which are not uncommon among adult women living in high-stress environments (Grienenberger et al., 2005; Slade, Grienenberger, et al., 2005). It was, therefore, not surprising that our themes from the qualitative analysis were predominantly based in concrete and tangible content areas. The narratives reflect a spectrum of cognitive styles ranging from very concrete thinking (in 8 participants) to somewhat more sophisticated thinking abilities (in 6 participants). The latter group seemed more able to consider the future, reflect on their own experiences, and consider the thoughts and perspectives of significant others. However, the majority of teens (16 participants) figuratively had a foot in both concrete and abstract cognitive worlds. At times, they demonstrated very concrete thinking as well as unrealistic ideas about such things as finances and what it would be like to actually support and care for a baby. At other times, however, these same participants demonstrated more reflective capacities, such as awareness that babies need to feel loved and develop attachment with their parents.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that it is the first study to begin to describe RF within a sample of pregnant adolescents. One limitation is that, although all participants were fluent in English, some Spanish-speaking participants (73% of the sample were Latina) may have had difficulty understanding some nuances in questions or expressing some responses. In addition, in these interviews, the young women were being asked to talk about feelings with a relative stranger (interviewer), which might have seemed like unfamiliar territory, and this possible discomfort or unfamiliarity with discussing feelings may also have limited their responses.

Implications for Clinical Practice and Further Research

Our findings provide an initial window into understanding how teens see themselves at this critical juncture in late pregnancy. Based on these insights, we suggest some ways to help teen mothers to become more reflective and sensitive parents. Clinicians who work with pregnant adolescents with similar backgrounds, may find it useful to assess how able they are to be reflective about their own mental states and the needs of their unborn infants. This knowledge enables clinicians to meet the teen where she is developmentally and help her gain reflective capacities as she matures as a teen and a parent. Clinical care and counseling may include the clinician modeling a reflective stance, reviewing video-recorded interactions between mothers and infants, naming feelings (in the mother and the baby) or speaking for the mother or for the baby concerning emotions that underlie behaviors. These approaches often help move teens into more reflective and cognitively mature ways of thinking about themselves, their relationships and their new roles as mothers (Mayers, 2005; Mayers et al., 2008; Mayers & Seigler, 2004; Sadler et al., 2006).

Longitudinal studies, following the changing RF patterns in young teen parents from pregnancy into parenthood, are needed for a clearer understanding of the simultaneous behavioral and neuro-developmental processes of teen mothers as they continue to mature. This parental development happens within the context of the growing maturing child (as he or she becomes more developmentally complex) and of the growing relationship between mother and child. Research is needed about additional approaches for helping adolescent parents develop reflective capacities. Helping teens to enhance their reflective capacities may also hold promise for counseling teen mothers about understanding and negotiating challenging relationships with partners. Finally, future research should examine how the capacity for RF develops within very young (< 15 years of age) mothers over time from pregnancy into parenthood.

Conclusions

In our sample of young pregnant women, the unique developmental characteristics of adolescence appeared to be intricately aligned with their developing capacities for parental reflectiveness, although this relationship needs further study. Understanding distinctive features of RF in adolescents will contribute to developing conceptual models and new clinical approaches for enhancing parental reflectiveness and sensitivity, and making possible more securely attached children being raised by young parents.

Highlights Revised.

Reflective functioning is thought to be an essential component of sensitive parenting, but not well studied or understood in pregnant and parenting teens.

In this qualitative study, guided by interpretive description, pregnant teens’ experiences of pregnancy and thoughts about parenting were complicated by their own developmental challenges and their complex social environments.

Most young women in this study relied upon family for support, yet had difficult and often ambivalent relationships with partners.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the following sources of funding support: T32-NR008346-07, NINR F31NR009911, NIH/CTSA (UL1RR024139), NINR (P30NR08999), NICHD (R21HD048591), and NICHD (RO1HD057947), the Irving B. Harris Foundation, the FAR Fund, the Donaghue Foundation, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Pritzker Early Childhood Foundation, the Seedlings Foundation, the Child Welfare Fund, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the Edlow Family, and the Schneider Family. We wish to thank our study participants and Dr. Arietta Slade for her thoughtful and insightful review of our manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lois S. Sadler, Email: Lois.sadler@yale.edu, Yale University School of Nursing, Yale Child Study Center, Yale University West Campus, 400 West Campus Drive, Orange, CT 06477.

Gina Novick, Email: Gina.novick@yale.edu, Yale University School of Nursing, Yale University West Campus, 400 West Campus Drive, Orange, CT 06477.

Mikki Meadows-Oliver, Email: Mikki.meadows-oliver@yale.edu, Yale University School of Nursing, Yale University West Campus, 400 West Campus Drive, Orange, CT 06477.

References

- Ayers L, Kavanaugh K, Knafl K. Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(6):871–883. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013006008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of mothering: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbassat N, Priel B. Parenting and adolescent adjustment: The role of parental reflective function. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli J, Compare A, Snavely J, Decio V. Reflective functioning moderates the association between perception of parental neglect and attachment in adolescence. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2014;32(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Carrano J, Horowitz A, Kinukawa A. Involvement among resident fathers and links to infant cognitive outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(9):1211–1244. doi: 10.1177/0192513x08318145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. The Social Ecological Model: A framework for prevention. 2007 Retrieved August 26, 2015, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Courtois C. Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice and Training. 2008;41:412–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne CA, D’Onofrio BM. Some (But Not Much) Progress Toward Understanding Teenage Childbearing. A Review of Research from the Past Decade. 2012;42:113–152. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-394388-0.00004-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers I, Bernier A, Tarabulsy GM, Provost M. Mind-mindedness in adult and adolescent mothers: Relations to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:529–537. [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D. Cognitive development. In: Friedman SB, et al., editors. Comprehensive adolescent health care. 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JL, Browning CR. Neighborhood social disorganization and the acquisition of trichomoniasis among young adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:1696–1703. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JL, Rechel M. Parental perceptions of the neighborhood context and adolescent depression. Public Health Nursing. 2012;29:390–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourquier K. State of the science: Does the theory of maternal role attainment apply to African American motherhood? Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013;58(2):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futris T, Schoppe-Sullivan S. Mothers’ perceptions of barriers, parenting alliances and adolescent fathers’ engagement with their children. Family Relations. 2007;56:258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger J, Kelly K, Slade A. Maternal reflective functioning, mother-infant affective communication and infant attachment: Exploring the link between mental states and observed care-giving behavior. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7(3):299–311. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha C, Sharp C, Ensink K, Fonagy P, Cirino P. The measurement of reflective functioning in adolescents with and without borderline traits. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:1215–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg BA. Psychosocial development. In: Friedman SB, et al., editors. Comprehensive adolescent health. 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe E, Petersen K, Manlove J. Ten reasons to still keep the focus on teen childbearing. Child Trends Research Brief. 2009;2009(10):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Levy D, Truman S, Mayes L. The impact of prenatal cocaine use on maternal reflective functioning. Paper presented at the Paper presented at the Biennial Meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development; Minneapolis, MN. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton B, Osteman M, Curtin S, Mathews T. Births: Final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2015;64(1):1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers H. Treatment of a traumatized adolescent mother and her two year old son. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2005;33:419–431. [Google Scholar]

- Mayers H, Hager-Budny M, Buckner EB. The Chances for Children teen parent-infant project: Results of a pilot intervention for teen mothers and their infants in inner city high schools. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2008;29:320–342. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers H, Seigler A. Finding each other: Using a psychoanalytic developmental perspective to build understanding and strengthen attachment between teenaged mothers and their babies. Journal of Infant, Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 2004;3:444–465. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Decker M, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway J, Silverman J. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2007;7:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Brooks-Gunn J. Adolescent parenthood. In: Bornstein EM, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2. Vol. 4. Mahwah, NJ: Earlbaum; 2002. pp. 173–214. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty Daley A, Sadler LS, Dawn Reynolds H. Tailoring Clinical Services to Address the Unique Needs of Adolescents from the Pregnancy Test to Parenthood. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2013;43(4):71–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2013.01.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander S, Black M, Starr R. African American adolescent mothers and grandmothers: A multigenerational approach to parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Slade A, Dixon J, Close N, Mayes L. Lasting effects of an interdisciplinary home visiting program on child behavior: Preliminary follow-up results of a randomized trial. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2014;29:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler D. Pregnant adolescents’ perspectives of pregnancy. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2003;28:377–383. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesch S, Anderson L, Pridham K, Lutz K, Becker P. Furthering the understanding of parent-child relationships: A nursing scholarship review servies. Part 5: Parent-adolescent and teen parent-child relationships. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2010;15(3):182–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers BL, Cowles KV. The qualitative audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing and Health. 1993;16:219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Anderson SA, Sabatelli RM. Parental competence among African American adolescent mothers and grandmothers. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001;16:217–233. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.25532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Clemmens D. Ambivalent young grandmothers raising teen mothers and their babies. Journal of Family Nursing. 2004;10:211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Cowlin A. Moving into parenthood: A program for new adolescent mothers combining parent education with creative physical activity. Journal of Specialists in Pediatric Nursing. 2003;8:62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2003.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Moriarty Daley A. A model of teen-friendly care for young women with negative pregnancy test results. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2002;37:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(02)00018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, Webb D, Simpson T, Fennie K, Mayes L. Minding the Baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2013;34(5):391–405. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Mayes L. Minding the baby: A mentalization-based parenting program. In: Allen JG, Fonagy P, editors. Handbook of mentalization-based treatment. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2006. pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Scott ME, Steward-Streng NR, Manlove J, Moore KA. The characteristics and circumstances of teen fathers at the birth of their first child and beyond. Child Trends Research Brief 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. The pregnancy interview. The Psychological Center. The City College of New York; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7(3):269–281. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. Reflective parenting programs: Theory and development. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2007;26(4):640–657. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Belsky J, Aber JL, Phelps J. Maternal representations of their relationship with their toddlers: Links to adult attachment and observed mothering. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:611–619. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Cohen LJ, Sadler LS, Miller M. The psychology and psychopathology of pregnancy: Reorganization and transformation. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of Infant Mental Health. 3. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Director L, Grunebaum L, Huganir L, Reeves M. Representational and behavioral correlates of pre-birth maternal attachment. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Seattle, WA. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Grienenberger J, Bernbach E, Levy D, Locker A. Maternal reflective functioning and attachment: Considering the transmission gap. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:283–292. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Patterson M, Miller M. The pregnancy interview manual. The Psychological Center. The City College of New York; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Sadler LS. Minding the Baby: Complex trauma and home visiting. International Journal of Birth and Parent Education. 2013;1(1):50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Sadler LS, de Dios-Kenn C, Webb D, Ezepchick J, Mayes LC. Minding the Baby: A reflective parenting program. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 2005;60:74–100. doi: 10.1080/00797308.2005.11800747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SmithBattle L. Moving policies upstream to mitigate the social determinants of early childbearing. Public Health Nursing. 2012;29(5):444–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear H. Teenage pregnancy: “Having a baby won’t affect me that much”. Pediatric Nursing. 2001;27:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Simon C, Beach R, Klerman LV. To be rather than not to be: That is the problem with the questions we ask adolescents about their childbearing intentions. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155:1298–1300. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-Humen E, Manlove J, Moore K. Playing catch-up: How children born to teen mothers fare. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Interpretive description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in Interpretive Description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2004;3(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Whitman TL, Borkowski J, Keogh D, Weed K. Interwoven lives. Mahwah: Lawrence Earlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]