Abstract

Intermittent mildly stressful situations provide opportunities to learn, practice, and improve coping with gains in subsequent emotion regulation. Here we investigate the effects of learning to cope with stress on anterior cingulate cortex gene expression in monkeys and mice. Anterior cingulate cortex is involved in learning, memory, cognitive control, and emotion regulation. Monkeys and mice were randomized to either stress coping or no-stress treatment conditions. Profiles of gene expression were acquired with HumanHT-12v4.0 Expression BeadChip arrays adapted for monkeys. Three genes identified in monkeys by arrays were then assessed in mice by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Expression of a key gene (PEMT) involved in acetylcholine biosynthesis was increased in monkeys by coping but this result was not verified in mice. Another gene (SPRY2) that encodes a negative regulator of neurotrophic factor signaling was decreased in monkeys by coping but this result was only partly verified in mice. The CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin (also called TARP gamma-2) was increased by coping in monkeys as well as mice randomized to coping with or without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. As evidence of coping effects distinct from repeated stress exposures per se, increased stargazin expression induced by coping correlated with diminished emotionality in mice. Stargazin modulates glutamate receptor signaling and plays a role in synaptic plasticity. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity that mediate learning and memory in the context of coping with stress may provide novel targets for new treatments of disorders in human mental health.

Keywords: learning, memory, emotion regulation, synaptic plasticity, CACNG2

1. Introduction

Deleterious effects of stress are well recognized in disorders of human mental health. Severe chronic stress is a risk factor for major depression and anxiety disorders (Charney and Manji, 2004; Krishnan and Nestler, 2008; Duman, 2009; Heim et al., 2010). Fewer studies have addressed the discovery that mild but not minimal nor severe stress exposure promotes subsequent coping and emotion regulation as described by U-shaped functions (Seery et al., 2010; Russo et al., 2012; Sapolsky, 2015). In addition to the qualities or intensities of stress exposure, temporal aspects further contribute to the production of stress vulnerability versus resilience (Burchfield, 1979). Chronic or prolonged stress leads to vulnerability (Brosschot, 2010) whereas intermittent stress exposures interspersed with undisturbed periods of recovery provide repeated opportunities to learn, practice, and improve coping with subsequent gains in emotion regulation and resilience (Lyons et al., 2009; Lyons et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014; Brockhurst et al., 2015).

Recently we found that learning to cope protects monkeys against subsequent stress induced deficits in behavior on tests of emotionality and diminishes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis neuroendocrine stress response (Lee et al., 2014). Similar learning to cope effects were then found for mice monitored on tail-suspension, open-field, and novel object-exploration tests (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Experimental learning to cope training sessions increase adult monkey hippocampal neurogenesis and alter the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and survival (Lyons et al., 2010). Gene expression profiles for prefrontal brain regions are also modified by stress in monkeys (Karssen et al., 2007) but coping effects in anterior cingulate cortex are not known. Anterior cingulate cortex is involved in learning, memory, cognitive control, emotion, and HPA axis regulation (Etkin et al., 2011; Ochsner et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Herman, 2013; Weible, 2013).

Here we investigate stress coping effects on anterior cingulate cortex gene expression in monkeys and mice. Experimental learning to cope training sessions acutely increase glucocorticoids (Brockhurst et al., 2015) and therefore a secondary exploratory aim of this study is to examine glucocorticoid signaling as a potential mechanism for differential gene expression. Genes potentially regulated by glucocorticoids and that serve relevant neural functions (see Discussion section below) for learning to cope modeled in monkeys were then assessed in mice. Diverse convergent evidence from monkeys and mice was sought to minimize false positive findings and enhance translational relevance (Ciesielski et al., 2014). Translation has commanded considerable attention because of recent uncertainties about generalization across different species given inevitable biological variation, the use of diverse experimental manipulations, and various ways to operationalize complex outcomes of interest (Institute of Medicine, 2013). Replication across distinct models that utilize different species may help to ensure that observed biological effects generalize to a broader context.

Promising results were obtained for the CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin (also called TARP gamma-2) with increased anterior cingulate cortex expression induced by coping in monkeys. This result was fully verified in mice randomized to coping with or without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. Increased stargazin expression induced by coping correlated with diminished measures of emotionality in mice. Stargazin modulates glutamate receptor signaling via AMPA receptor trafficking (Chen et al., 2000; Vandenberghe et al., 2005; Jackson and Nicoll, 2011) and plays a role in synaptic plasticity (Huganir and Nicoll, 2013) as a mechanism for learning considered functionally in terms of behavior change. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity that mediate learning and memory in the context of coping with stress may provide novel targets for new treatments of disorders in human mental health.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 22 male squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) and 48 male C57BL/6 mice (Mus musculus) served as subjects. Monkeys were born and raised at the Stanford University Research Animal Facility and were studied in adulthood at ~9 yr of age (range 7.2-10.6 yr). Mice weighing ~25 g (range 22-28 g) were purchased from Charles River (Holister, CA) and acclimated to our research animal facility for 2 wk. All animals were maintained in species appropriate conditions at ~26°C on 12:12 hr light/dark cycles with lights on at 07:00 hr.

Monkey cages were cleaned daily, mouse cages were cleaned weekly, and all animals were provisioned with fresh drinking water and commercial chow ad libitum. Monkeys were additionally provided fruit and vegetable supplements as well as various toys, swinging perches, and simulated foraging activities for environmental enrichment. All procedures were conducted in accordance with state and federal laws, standards of the Department of Health and Human Services, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University.

2.1. Experimental design for monkeys

Ten monkeys were randomized to the no-stress control treatment condition in which they lived undisturbed with a familiar same-sex companion in pairs. The other 12 age-matched monkeys were randomized to the stress coping condition. These monkeys were temporarily separated from same-sex companions and housed for 3 wk alone. During each separation, monkeys were individually maintained in cages that allowed visual, auditory, olfactory, and limited tactile contact between adjacent animals. Social separations acutely increase plasma levels of the stress hormone cortisol in adult male squirrel monkeys (Karssen et al., 2007). After each separation, monkeys were returned to social housing and maintained for 9 wk in pairs. Separations were repeated at 12 wk intervals to provide 6 intermittent opportunities for learning to cope with stress.

Noninvasive brain imaging and neuroendocrine tests of glucocorticoid feedback regulation of the HPA axis were conducted before and after completion of the treatment conditions for all monkeys (Lyons et al., 2007). Behavioral tests of learning and memory were also conducted at 3-mo intervals throughout both treatment conditions (Lyons et al., 2010). Intravenous injections of BrdU were administered 12 wk before the collection of brain tissues for assessments of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (Lyons et al., 2010). Brain tissues for the present study were obtained from randomly selected monkeys in the stress coping (N=6) and no-stress (N=6) conditions 4 wk after the last social separation when all monkeys were housed in pairs.

2.2. Experimental design for mice

A total of 24 mice were randomized to the no-stress control treatment condition in which they lived undisturbed in groups each comprised of 3 familiar same-sex companions. The other 24 age-matched mice were randomized to the stress coping condition. These mice were removed from the home cage every other day for 21 days and individually placed for 15 min behind a mesh-screen barrier in the cage of a retired Swiss Webster male mouse breeder. Each subject was repeatedly exposed to the same resident with different residents used for different subjects to avoid idiosyncratic effects. The mesh-screen barrier prevented fighting and wounding during all 11 encounters with the resident stranger but allowed non-contact interactions. Repeated encounters with a same-sex stranger acutely increase plasma levels of the stress hormone corticosterone in male mice (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Immediately after each encounter, subjects were returned to the home cage.

Subsequent behavioral measures of emotionality on tail-suspension, open-field, and object-exploration tests were collected 2-13 days after completion of the treatment conditions from 12 mice in each condition (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Brains were then collected 3 days after the behavioral tests of emotionality. To distinguish prior stress coping effects from experience-dependent transcriptional responses attributable to the behavioral tests, 12 mice from both treatment conditions were not tested for emotionality and remained undisturbed for 8 days before brain collections.

2.3. Brain collections

Brains were collected and processed with established methods in the mornings to control for circadian effects. Briefly, brains were harvested, flash frozen in isopentane at −20°C, and stored at −80°C. Frozen blocks of brain tissue were cut with RNAse-free methods on a cryostat for monkeys or with a brain matrix slicer for mice. From mice, we bilaterally dissected anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus with RNAse-free methods at −20°C using a 0.95mm diameter punch (de Kloet, 2006) and mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2008). From monkeys, anterior cingulate cortex was dissected at the corpus callosum on the left brain side from randomly selected coronal sections at ~0°C using RNAse-free instruments described elsewhere (Karssen et al., 2007) and a squirrel monkey brain atlas (Gergen and MacLean, 1962).

2.4. BeadChip arrays

Tissue samples from monkeys were homogenised with a motorised pellet pestle and total RNA was extracted using AllPrep DNA/RNA Micro kits (Qiagen). Quantification was carried out by spectrophotometric analysis. All samples were amplified (RiboAmp Plus 1.5-round RNA Amplification, Applied Biosystems) for production of biotinylated cRNA (Bioarray High Yield RNA Labeling, ENZO) and subsequently hybridized to HumanHT-12v4.0 Expression BeadChip arrays (Illumina) that were scanned on a BeadStation system following manufacturer’s instructions. Twelve BeadChip arrays were used to generate gene expression profiles for monkey anterior cingulate cortex (N=6 per treatment condition). No pooling of samples was necessary. Stress coping and no-stress conditions were randomly counterbalanced across separate BeadChip arrays.

2.5. Array data processing

Each BeadChip array has more than 47,000 probes designed for humans. To select probes suited for squirrel monkeys, we compared probe sequences against the squirrel monkey genome (Broad Institute, GCA_000235385.1) using BLAT (Kent, 2002). Selected probes were required to match a single continuous segment of the squirrel monkey genome at 95% homology or greater. For the 11,209 selected probes, expression values were imported into R (R Core Team, 2013), background corrected using maximum likelihood estimation (Xie et al., 2009), log2 transformed, and quantile normalized. Normalized data were determined to be free of outliers by analysis of box plots. Probes not associated with known genes were discarded. Using these procedures, we selected 8,853 probes interrogating 7,299 unique genes for further analysis.

2.6. Verification by qPCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used to verify differential expression of genes identified in monkeys by arrays using brain tissue samples from mice. Tissue samples from mice were collected in RLT buffer (Qiagen), homogenized with a motorised pellet pestle, and frozen at −80°C until extraction using AllPrep DNA/RNA Micro kits (Qiagen). One mouse brain was excluded from further analysis because of poor quality unrelated to the study. Primers for qPCR reactions (Table 1) were designed with Primer-BLAST (NCBI) for Sybr Green assays with parameters such as GC clamp and poly-x 3’ set as described elsewhere (Thornton and Basu, 2011). Oligo dimerization and amplicon secondary structures were respectively predicted with Beacon Designer and mFold. Assays were optimized by testing for specificity, efficiency, and linearity with 5 serial dilutions. Reactions for qPCR were then conducted following manufacturer’s instructions (Biorad, SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green) with the following conditions: 250 nM primers, 50 mM Na+, 3 mM Mg++, and 1.2 mM dNTP, using MxPro3000 (Stratagene). All assays were optimized at 60°C as the annealing temperature with 40 cycles of amplification followed by melt-curve analysis. Results are reported as described elsewhere (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) with ACTB as the reference gene.

Table 1.

Primers specified from 5’ to 3’ for qPCR in mice.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| CACNG2 | CTGTGCAAGCAAATCGACCA | CACACTCAGGATCGGGAAGA |

| SPRY2 | TTGCACATCGCTGGAAGAAGA | CTGGCCTCCATCAGGTCTT |

| PEMT | GTTTGTGCTGTCCAGCTTCTATG | GGAAATGTGGTCACTCTGGAC |

| ACTB | ATGTGGATCAGCAAGCAGGA | AAACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTC |

2.7. Statistical analysis

Array probes with log2 fold change scores ≥0.8 (which equals 1.75 for non-transformed raw data) were assessed using t-tests in R (R Core Team, 2013) with stress coping versus no-stress treatment conditions considered a between-subjects factor. To further explore differential expression, the list of genes with stress coping effects in monkeys was uploaded into the Functional Annotation Tool of DAVID 6.7 (Huang da et al., 2009). Using UCSC_TFBS in the Protein Interactions option, enrichment statistics were computed with Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing.

Three genes identified in monkeys by arrays were subsequently assessed in mice by qPCR with 2-way analysis of variance and Tukey post hoc pairwise comparisons. Stress coping and subsequent behavioral test conditions were both considered between-subjects factors to distinguish coping effects from responses elicited by behavioral tests of emotionality. Pearson correlations were used to test for associations between gene expression and previously reported measures of emotionality in monkeys (Lyons et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2010) and mice (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Coping induced changes in gene expression were also examined in the amygdala and hippocampus of mice with t-tests. All test statistics were evaluated with two-tailed probabilities at P<0.05.

3. Results

All array data are available for public use at https://pritzkerneuropsych.org/www/data/. Stress coping effects on anterior cingulate cortex gene expression in monkeys were discerned for 290 probes targeting 285 unique genes (P<0.05, Supplementary Material Table S1). Stress coping compared to the no-stress condition increased expression of 108 genes (37.2%) and decreased expression of 182 genes (62.8%). Changes induced by coping were modest in magnitude and similar for genes with increased (mean log2 fold change = 0.98, range 0.81 to 1.83) or decreased (mean log2 fold change = −1.06, range −0.81 to −1.75) expression compared to the no-stress condition.

Because intermittent stress coping repeatedly increases glucocorticoids (Brockhurst et al., 2015), we first explored glucocorticoid signaling as a potential mechanism for differential gene expression. Of the 290 probes with stress coping effects in monkeys, 152 (52.4%) probes targeted genes that have a glucocorticoid receptor binding site determined by UCSC_TFBS in DAVID 6.7 (Bonferroni corrected P=0.026). An equal number of probes targeted genes with sequence motifs for a canonical glucocorticoid response element (Bonferroni corrected P<0.001). Ninety four probes (32.4%) targeted genes associated with both of these factors, 118 probes (40.7%) targeted genes associated with a single factor, and 78 probes (26.9%) targeted genes not associated with either factor for transcription regulation by glucocorticoids (Supplementary Material Table S1).

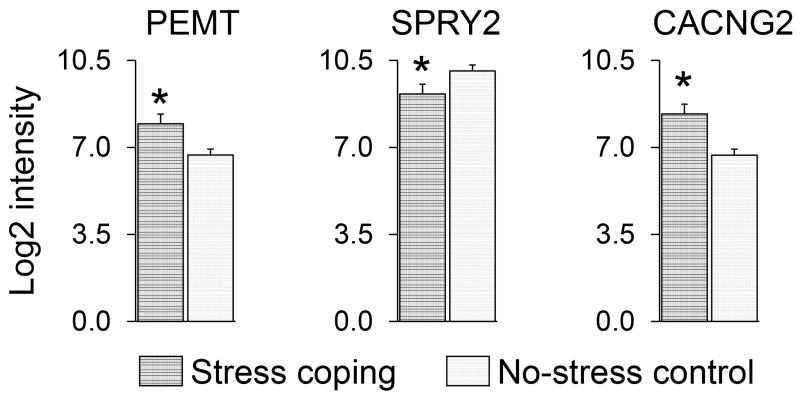

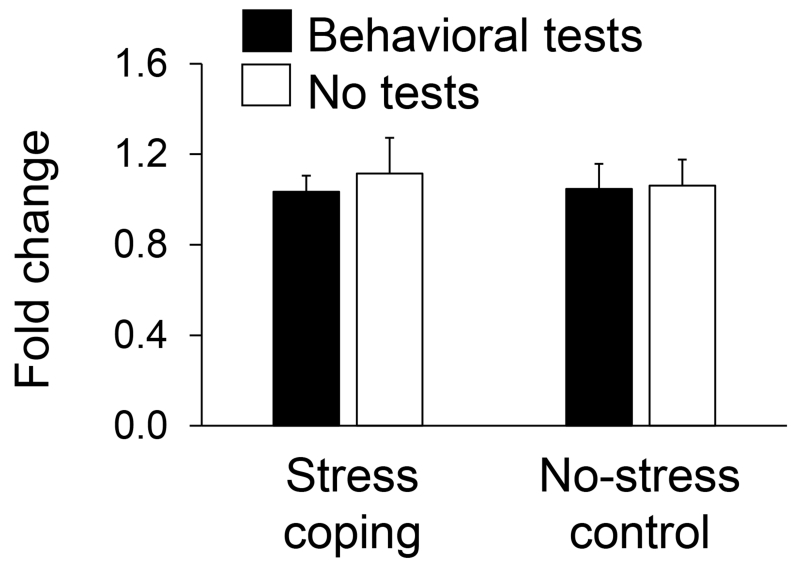

Three genes potentially regulated by glucocorticoids with stress coping effects in monkeys identified by arrays were subsequently assessed by qPCR in mice. A key gene (PEMT) involved in acetylcholine biosynthesis was increased in monkeys by coping (t(10)=2.72, P=0.02; Figure 1) but this result was not confirmed in mice (Figure 2). Neither coping nor subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality altered anterior cingulate cortex expression of PEMT in mice.

Figure 1.

PEMT, SPRY2, and CACNG2 expression in anterior cingulate cortex determined by arrays for monkeys randomized to stress coping versus no-stress conditions (N=6 per condition; mean±SEM; *P<0.05).

Figure 2.

PEMT expression in anterior cingulate cortex determined by qPCR for mice randomized to stress coping versus no-stress conditions with and without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality (N=11-12 per condition; mean±SEM).

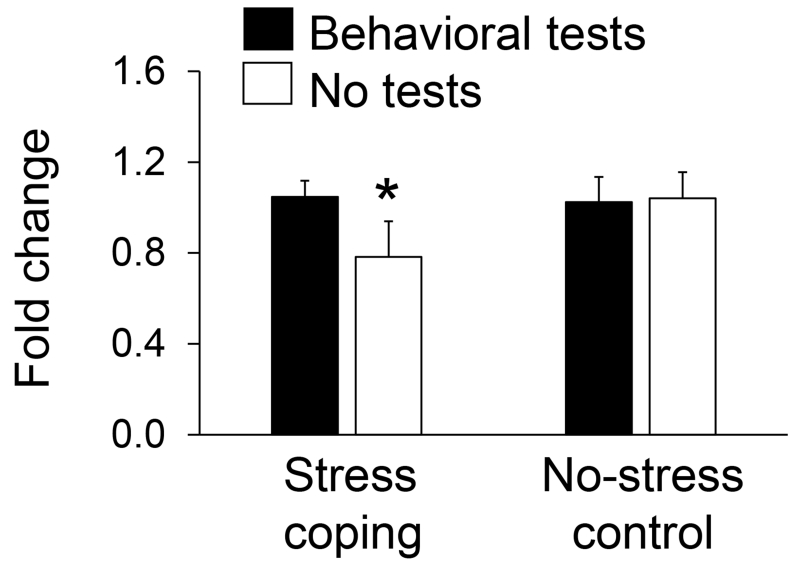

Another gene (SPRY2) that encodes a negative regulator of neurotrophic factor signaling was decreased in monkeys by coping (t(10)=2.68, P=0.02; Figure 1) but this result was only partly verified in mice (Figure 3). SPRY2 expression in anterior cingulate cortex was decreased by coping only in mice not exposed to subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. This result was confirmed by the coping-by-test condition interaction (F(1,43)=4.02, P=0.05) with decreased SPRY2 expression after coping in mice not exposed to behavioral tests compared to those behaviorally tested for emotionality (Tukey test, P=0.047).

Figure 3.

SPRY2 expression in anterior cingulate cortex determined by qPCR for mice randomized to stress coping versus no-stress conditions with and without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality (N=11-12 per condition; mean±SEM; *P<0.05).

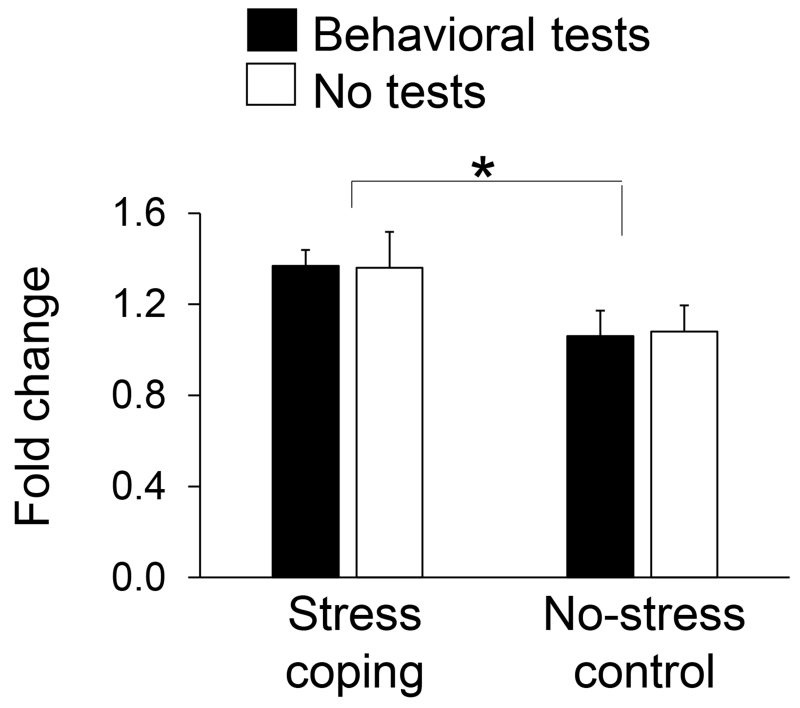

The CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin was increased in monkeys by coping (t(10)=2.52, P=0.03; Figure 1) and this finding was fully verified in mice (Figure 4). A significant coping main effect was discerned for mice (F(1,43)=6.23, P=0.016) but neither the test condition main effect nor coping-by-test condition interaction were significant. As evidence for coping effects distinct from repeated stress exposures per se, increased stargazin expression in anterior cingulate cortex correlated inversely with behavioral measures of emotionality in mice. Specifically, increased anterior cingulate cortex expression of stargazin in mice correlated with diminished latencies to explore a novel object (r = −0.53, df 21, P=0.009) and with diminished immobility as measure of behavioral despair on tail-suspension tests (r = −0.50, df 21, P=0.016). Anterior cingulate cortex stargazin expression did not correlate with freezing in the open-field.

Figure 4.

CACNG2 expression in anterior cingulate cortex determined by qPCR for mice randomized to stress coping versus no-stress conditions with and without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality (N=11-12 per condition; mean±SEM; *P<0.05).

Increased stargazin expression induced by coping in mice was also nearly significant in amygdala (1.20±0.09 for stress coping versus 1.01±0.05 in the no-stress condition, mean±SEM, t(21)=1.76, P=0.093) and not hippocampus. Increased amygdala stargazin expression correlated inversely with diminished tail-suspension immobility (r = −0.42, df 21, P=0.044) but not novel object exploration nor freezing in the open-field. Stargazin expression in hippocampus was not correlated with any behavioral measure of emotionality in mice.

Stargazin expression was not measured in mice monitored for neuroendocrine responses but stargazin expression tended to correlate inversely with neuroendocrine restraint stress responses in monkeys (r = −0.40, df 10, P=0.201). Although this correlation is similar in magnitude to those described above for mice, it is not statistically significant for our small sample of monkeys. Stargazin expression was not measured in monkeys monitored on behavioral tests of emotionality, but the correlation for anterior cingulate cortex stargazin expression in monkeys and learning inferred from behavior was nearly statistically significant (r = 0.55, df 10, P=0.064).

4. Discussion

Three genes identified in monkey anterior cingulate cortex by arrays were assessed in in anterior cingulate cortex of mice by qPCR. Measures from monkeys and mice were analyzed for convergence to minimize false positive findings and enhance translational relevance. The PEMT gene involved in acetylcholine biosynthesis (Blusztajn and Wurtman, 1983; Zeisel, 2012) was increased in monkeys by coping but this result was not confirmed in mice. The SPRY2 gene that encodes a negative regulator of neurotrophic factor signaling (Kramer et al., 1999; Cabrita and Christofori, 2003; Rubin et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005; Gross et al., 2007) was decreased in monkeys by coping but this result was only partly verified in mice. The CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin was increased by coping in monkeys as well as mice randomized to coping with or without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. As evidence of coping effects distinct from repeated stress exposures per se, increased stargazin expression correlated inversely with behavioral measures of emotionality in mice. Increased stargazin expression induced by coping in mice was also nearly significant for amygdala but not hippocampus.

Results from monkeys were verified by testing for convergence in mice because many genes identified in monkeys by arrays did not meet multiple testing adjustments for P-value thresholds. Convergent evidence from diverse sources avoids problems with adjustments in P-value thresholds (Ciesielski et al., 2014; Nuzzo, 2014). Different stress coping conditions were designed on the basis of evidence that mild intermittent but not minimal nor severe stress exposure provides opportunities to learn, practice, and improve coping as described by U-shaped functions (Seery et al., 2010; Russo et al., 2012; Sapolsky, 2015). Intermittent social separations have been discussed in earlier studies of coping for monkeys (Lyons et al., 2009; Lyons et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2014) and a standard social stress protocol was modified to create experimental conditions for studies of coping in mice (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Our finding that these different conditions consistently increased stargazin expression in anterior cingulate cortex of monkeys and mice supports the possibility that an aspect of coping is mediated by a common underlying neural mechanism.

One potential mediating mechanism is suggested by our earlier observation that experimental learning to cope training sessions acutely increase glucocorticoids (Brockhurst et al., 2015). Glucocorticoids are transformed into genomic outputs by binding intracellular glucocorticoid receptors that translocate to the nucleus and interact with DNA to regulate the expression of numerous genes (Oakley and Cidlowski, 2013; Zalachoras et al., 2013). Many genes differentially expressed with intermittent coping in monkeys appear to interact with glucocorticoids according to our analysis using UCSC_TFBS in DAVID 6.7, including the three genes we examined in mice. Although data in GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) confirm transcription regulation by glucocorticoids, profiles of gene expression induced by temporal patterns of glucocorticoid exposure that mimic intermittent sessions of coping are not available. Intermittent versus chronic glucocorticoid exposure differentially regulates the expression of specific genes (Conway-Campbell et al., 2012) and broader profiles of gene expression are needed to determine whether this explains differing psychobiological effects of intermittent versus chronic stress.

Two of the three genes identified in monkeys that serve potentially relevant neural functions for coping as suggested by earlier research were not fully verified in mice. PEMT encodes an enzyme involved in acetylcholine biosynthesis (Blusztajn and Wurtman, 1983; Zeisel, 2012), for example, and acetylcholine has been implicated in rodent models of coping with stress (Martinowich et al., 2012; Garrido et al., 2013). But our results for PEMT did not generalize from monkeys to mice.

Another candidate gene we examined in mice is SPRY2, which encodes a protein that suppresses the actions of several neurotrophic factors (Kramer et al., 1999; Cabrita and Christofori, 2003; Rubin et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005; Gross et al., 2007) that may play role in coping with stress (Aizawa et al., 2015). Stress coping induced downregulation of SPRY2 observed in monkeys could therefore enhance neurotrophic actions and promote neural adaptations like those observed with decreased SPRY2 expression in rat models of electroconvulsive therapies for major depression (Ongur et al., 2007). Diminished SPRY2 expression induced by coping in monkeys was verified, however, only in mice not exposed to subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. Behavioral testing apparently abolished SPRY2 downregulation induced by coping in mice.

More promising results were obtained for the CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin with increased anterior cingulate cortex expression induced by coping in monkeys. This result was fully verified in mice randomized to coping with or without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. Increased anterior cingulate cortex stargazin expression induced by coping in mice correlated inversely with behavioral measures of emotionality. Increased stargazin expression induced by coping in mice was also nearly significant in amygdala but not hippocampus. Earlier array data likewise failed to show coping effects on stargazin expression in monkey hippocampus (Lyons et al., 2010). Stargazin modulates glutamate receptor signaling via AMPA receptor trafficking (Chen et al., 2000; Vandenberghe et al., 2005; Jackson and Nicoll, 2011) and plays a key role in synaptic plasticity (Huganir and Nicoll, 2013). Humans with major depression show decreased stargazin expression in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Beneyto and Meador-Woodruff, 2006) and antidepressant medications increase stargazin association with AMPA receptors in rats (Martinez-Turrillas et al., 2007).

Numerous studies of synaptic physiology have examined stargazin but fewer have linked stargazin to learning considered functionally in terms of behavior change. One report indicates that eyeblink conditioning increased stargazin expression in rat cerebellum (Kim and Thompson, 2011) and another study found that navigational learning increased stargazin expression in rat hippocampus (Blair et al., 2013). Here we report that learning to cope increased stargazin expression in anterior cingulate cortex of monkeys and mice. All these reports are correlational, however, and further studies are needed to establish causal links between learning reflected in behavior and increased stargazin expression in relevant regions of brain.

Our findings should be interpreted along with other potential limitations. Results from males may or may not hold true for females. Although experimental stress coping conditions enhance subsequent emotion regulation monitored in adult female monkeys (Lee et al., 2014), neurobiological mechanisms of coping in female mice have not been explored. Potentially important coping effects on gene expression may have escaped our attention because many of the array probes designed for humans were not suited for monkeys. Direct regulation of differential gene expression by glucocorticoids is considered in our analysis but indirect pathways that involve various glucocorticoid receptor co-regulators are not examined (Ratman et al., 2013). The pursuit of convergent evidence in monkeys and mice minimizes false positive findings and may enhance translational relevance (Ciesielski et al., 2014) but also increases the risk of falsely disregarding important species differences as negative results.

5. Conclusions

Three genes potentially regulated by glucocorticoids with stress coping effects in monkeys were assessed in mice. Promising results were obtained for the CACNG2 gene that encodes stargazin with increased anterior cingulate cortex expression induced by coping in monkeys. This result was fully verified in mice randomized to coping with or without subsequent behavioral tests of emotionality. Increased stargazin expression induced in anterior cingulate cortex by coping correlated with diminished measures of emotionality in mice. Increased stargazin expression induced by coping was also nearly significant in amygdala but not hippocampus. Stargazin modulates glutamate receptor signaling and plays a key role in synaptic plasticity via AMPA receptor trafficking. Molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity that mediate learning and memory in the context of coping with stress may provide novel targets for new treatments of disorders in human mental health.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Learning to cope with stress increases anterior cingulate cortex stargazin expression in monkeys and mice.

Convergent measures from monkeys and mice minimize false positive findings and may enhance translational relevance.

Many other studies show that stargazin plays a key role in synaptic plasticity.

Synaptic plasticity provides new targets for novel treatments that could facilitate learning to cope in humans.

Acknowledgements

Supported by Public Health Service Grant MH47573 and the Pritzker Neuropsychiatric Disorders Research Consortium Fund LLC. Funding agencies did not design the studies or write this report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Schatzberg reports equity in Merck, Pfizer, Neurocrine, XHale, and Corcept Therapeutics (co-founder). Dr. Schatzberg has received lecture fees from Merck and Pfizer and consulted to McKinsey, Takeda/Lundbeck, Pfizer, Depomed, Forum, One Carbon, Naurex, and Neuronetics. Drs. Lee, Capanzana, Brockhurst, Cheng, Buckmaster, Absher, and Lyons report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Aizawa S, Ishitobi Y, Masuda K, Inoue A, Oshita H, Hirakawa H, Ninomiya T, Maruyama Y, Tanaka Y, Okamoto K, Kawashima C, Nakanishi M, Higuma H, Kanehisa M, Akiyoshi J. Genetic association of the transcription of neuroplasticity-related genes and variation in stress-coping style. Brain Behav. 2015;5:e00360. doi: 10.1002/brb3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Meador-Woodruff JH. Lamina-specific abnormalities of AMPA receptor trafficking and signaling molecule transcripts in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Synapse. 2006;60:585–598. doi: 10.1002/syn.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair MG, Nguyen NN, Albani SH, L’Etoile MM, Andrawis MM, Owen LM, Oliveira RF, Johnson MW, Purvis DL, Sanders EM, Stoneham ET, Xu H, Dumas TC. Developmental changes in structural and functional properties of hippocampal AMPARs parallels the emergence of deliberative spatial navigation in juvenile rats. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12218–12228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4827-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blusztajn JK, Wurtman RJ. Choline and cholinergic neurons. Science. 1983;221:614–620. doi: 10.1126/science.6867732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhurst J, Cheleuitte-Nieves C, Buckmaster CL, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM. Stress inoculation modeled in mice. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e537. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF. Markers of chronic stress: prolonged physiological activation and (un)conscious perseverative cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchfield SR. The stress response: a new perspective. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:661–672. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita MA, Christofori G. Sprouty proteins: antagonists of endothelial cell signaling and more. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:586–590. doi: 10.1160/TH03-04-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS, Manji HK. Life stress, genes, and depression: multiple pathways lead to increased risk and new opportunities for intervention. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:re5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2252004re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski TH, Pendergrass SA, White MJ, Kodaman N, Sobota RS, Huang M, Bartlett J, Li J, Pan Q, Gui J, Selleck SB, Amos CI, Ritchie MD, Moore JH, Williams SM. Diverse convergent evidence in the genetic analysis of complex disease: coordinating omic, informatic, and experimental evidence to better identify and validate risk factors. BioData Min. 2014;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1756-0381-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway-Campbell BL, Pooley JR, Hager GL, Lightman SL. Molecular dynamics of ultradian glucocorticoid receptor action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER. From punch to profile. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:131–135. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-9014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS. Neuronal damage and protection in the pathophysiology and treatment of psychiatric illness: stress and depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:239–255. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/rsduman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido P, De Blas M, Ronzoni G, Cordero I, Anton M, Gine E, Santos A, Del Arco A, Segovia G, Mora F. Differential effects of environmental enrichment and isolation housing on the hormonal and neurochemical responses to stress in the prefrontal cortex of the adult rat: relationship to working and emotional memories. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2013;120:829–843. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen JA, MacLean PD. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Squirrel Monkey’s Brain (Saimiri sciureus) Public Health Service; Bethesda: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Gross I, Armant O, Benosman S, de Aguilar JL, Freund JN, Kedinger M, Licht JD, Gaiddon C, Loeffler JP. Sprouty2 inhibits BDNF-induced signaling and modulates neuronal differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1802–1812. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Shugart M, Craighead WE, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Dev Psychobiol. 2010;52:671–690. doi: 10.1002/dev.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP. Neural control of chronic stress adaptation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:61. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huganir RL, Nicoll RA. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: the last 25 years. Neuron. 2013;80:704–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Improving the utility and translation of animal models for nervous system disorders: workshop summary. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Nicoll RA. Stargazin (TARP gamma-2) is required for compartment-specific AMPA receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity in cerebellar stellate cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3939–3952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5134-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karssen AM, Her S, Li JZ, Patel PD, Meng F, Bunney WE, Jr., Jones EG, Watson SJ, Akil H, Myers RM, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM. Stress-induced changes in primate prefrontal profiles of gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:1089–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Thompson RF. c-Fos, Arc, and stargazin expression in rat eyeblink conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 2011;125:117–123. doi: 10.1037/a0022328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer S, Okabe M, Hacohen N, Krasnow MA, Hiromi Y. Sprouty: a common antagonist of FGF and EGF signaling pathways in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:2515–2525. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455:894–902. doi: 10.1038/nature07455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AG, Buckmaster CL, Yi E, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM. Coping and glucocorticoid receptor regulation by stress inoculation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;49:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DM, Buckmaster PS, Lee AG, Wu C, Mitra R, Duffey LM, Buckmaster CL, Her S, Patel PD, Schatzberg AF. Stress coping stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis in adult monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14823–14827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914568107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DM, Parker KJ, Katz M, Schatzberg AF. Developmental cascades linking stress inoculation, arousal regulation, and resilience. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:32. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.032.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DM, Parker KJ, Zeitzer JM, Buckmaster CL, Schatzberg AF. Preliminary evidence that hippocampal volumes in monkeys predict stress levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1171–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Turrillas R, Del Rio J, Frechilla D. Neuronal proteins involved in synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors in rat hippocampus by antidepressant drugs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinowich K, Schloesser RJ, Lu Y, Jimenez DV, Paredes D, Greene JS, Greig NH, Manji HK, Lu B. Roles of p75(NTR), long-term depression, and cholinergic transmission in anxiety and acute stress coping. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo R. Scientific method: statistical errors. Nature. 2014;506:150–152. doi: 10.1038/506150a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1033–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Silvers JA, Buhle JT. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251:E1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongur D, Pohlman J, Dow AL, Eisch AJ, Edwin F, Heckers S, Cohen BM, Patel TB, Carlezon WA., Jr. Electroconvulsive seizures stimulate glial proliferation and reduce expression of Sprouty2 within the prefrontal cortex of rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in sterotaxic coordinates. Elsevier; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ratman D, Vanden Berghe W, Dejager L, Libert C, Tavernier J, Beck IM, De Bosscher K. How glucocorticoid receptors modulate the activity of other transcription factors: a scope beyond tethering. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;380:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin C, Litvak V, Medvedovsky H, Zwang Y, Lev S, Yarden Y. Sprouty fine-tunes EGF signaling through interlinked positive and negative feedback loops. Curr Biol. 2003;13:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Murrough JW, Han MH, Charney DS, Nestler EJ. Neurobiology of resilience. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1475–1484. doi: 10.1038/nn.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Stress and the brain: individual variability and the inverted-U. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1344–1346. doi: 10.1038/nn.4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:1025–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0021344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton B, Basu C. Real-time PCR (qPCR) primer design using free online software. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2011;39:145–154. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe W, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Stargazin is an AMPA receptor auxiliary subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:485–490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408269102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SH, Tse D, Morris RG. Anterior cingulate cortex in schema assimilation and expression. Learn Mem. 2012;19:315–318. doi: 10.1101/lm.026336.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weible AP. Remembering to attend: the anterior cingulate cortex and remote memory. Behav Brain Res. 2013;245:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Wang X, Story M. Statistical methods of background correction for Illumina BeadArray data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:751–757. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalachoras I, Houtman R, Meijer OC. Understanding stress-effects in the brain via transcriptional signal transduction pathways. Neuroscience. 2013;242:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel SH. A brief history of choline. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61:254–258. doi: 10.1159/000343120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Chaturvedi D, Jaggar L, Magnuson D, Lee JM, Patel TB. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by human sprouty 2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:533–538. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155461.50450.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.