Abstract

Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and pain is well-documented, but the mechanisms underlying their comorbidity are not well understood. Cross-lagged regression models were estimated with 3 waves of longitudinal data to examine the reciprocal associations between PTSD symptom severity, as measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS), and pain, as measured by a brief self-report measure of pain called the PEG (pain intensity [P], interference with enjoyment of life [E], and interference with general activity [G]). We evaluated stress appraisals as a mediator of these associations in a sample of low-income, underserved patients with PTSD (N = 355) at Federally Qualified Health Centers in a northeastern metropolitan area. Increases in PTSD symptom severity between baseline and 6-month and 6- and 12-month assessments were independently predicted by higher levels of pain (β = .14 for both lags) and appraisals of life stress as uncontrollable (β = .15 for both lags). Stress appraisals, however, did not mediate these associations, and PTSD symptom severity did not predict change in pain. Thus, the results did not support the role of stress appraisals as a mechanism underlying the associations between pain and PTSD.

Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and chronic pain is well documented, and recent research highlights their longitudinal, mutually reinforcing associations (Beck & Clapp, 2011). Less well understood are the mechanisms that underlie their associations. Understanding the mechanisms through which pain and PTSD mutually reinforce each other is critical to informing and refining theoretical models of their interrelationships. Current theoretical conceptualizations delineate multiple mechanisms that might underlie these associations, including, but not limited to, attentional biases toward trauma- and pain-related cues, trauma reminders, avoidant coping, and cognitive demands that diminish coping ability (Asmundson, Coons, Taylor, & Klatz, 2002; Beck & Clapp, 2011; Sharp & Harvey, 2001).

In a recent review, appraisals of life control were identified as another possible mechanism underlying these associations (Beck & Clapp, 2011). Individuals with PTSD might have difficulty managing their symptoms and perceive them as uncontrollable, thus fueling appraisals of stress as uncontrollable. These appraisals might then impose cognitive demands that reduce cognitive resources for coping with pain and, as a result, increase pain. These linkages might also operate in the reverse direction, such that pain increases appraisals of stressors as uncontrollable, which in turn exacerbates PTSD symptoms.

No studies of which we are aware have examined appraisals of life stress as a mechanism underlying the reciprocal, longitudinal associations between pain and PTSD. Evaluating stress appraisals as a mechanism (i.e., mediator) of the associations between pain and PTSD would require at least three waves of longitudinal data to obtain unbiased estimates of mediated effects (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Capitalizing on three waves of longitudinal data, the current study examined the reciprocal, longitudinal associations between PTSD symptoms and pain and evaluated the mediating role of stress appraisals. We hypothesized that PTSD and pain would have positive, reciprocal, longitudinal associations, and that stress appraisals would mediate these associations in both directions.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The current study was a secondary analysis of longitudinal data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a care management intervention for PTSD in primary care. Study participants were primary care patients recruited from six Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) across the New York City metropolitan area. These FQHCs serve a low-income population with a large proportion of Hispanic patients and are described in greater detail elsewhere (Meredith et al., 2014).

Recruitment coordinators first approached 8,422 patients in waiting rooms and screened them for eligibility in two stages. First, patients were screened for the basic eligibility requirements of being physically and cognitively able to participate (i.e., not acutely ill, able to understand information about the study), 18 to 65 years old, and English- or Spanish-speaking; having an appointment with a primary care clinician at the FQHC, planning to receive care from the same FQHC over the next year, and screening positive for PTSD (i.e., scoring 14 or higher) on an abbreviated version of the PTSD Checklist (Lang & Stein, 2005). There were 965 who satisfied the criteria and were invited to provide written informed consent and complete a PTSD diagnostic interview. Of the 587 who consented and completed the interview, 404 met criteria for PTSD and were randomized to the intervention or control condition. Of these, 355 (87.9%) completed the baseline interview and formed the sample for this study. The majority of randomized participants completed follow-up interviews 6 (59.2%, n = 239) and 12 months (66.1%, n = 267) after baseline. Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English according to the participant’s preference. Procedures were approved by RAND’s Human Subjects Protection Committee.

At baseline, participants’ mean age was 42.44 years old (SD = 12.18). The sample included mostly women (80.6%) and high proportions of Hispanic (51.8%) and black (35.4%) participants (6.0% white, 6.8% other). Nearly 40% had less than a high school education, 19.6% were immigrants, and 12.5% were interviewed in Spanish. Most participants had government-sponsored insurance such as Medicaid (88.9%) and had experienced at least three traumatic events (88.9%). Nearly one-third (28.3%) had at least three medical conditions, and 43.1% reported taking pain medication in the past 6 months; examples of pain medications taken include both those available over-the-counter (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) and by prescription only (e.g., opioids such as oxycodone).

Measures

Current DSM-IV PTSD diagnostic status and symptom severity were assessed with the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; (Blake et al., 1995), a structured diagnostic instrument that has been validated with varied traumatized populations in real world clinical settings (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). PTSD symptom severity scores were computed by summing the two 5-point (0-4) symptom ratings of frequency and intensity across the 17 symptoms. Anchors for ratings of symptom frequency were 0 = never, 1 = once or twice, 2 = once or twice a week, 3 = several times a week, 4 = daily or almost every day. Anchors for ratings of symptom intensity were 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = extreme. In the current study, internal consistency was adequate at each wave (Cronbach’s α = .82 to .93).

Pain was assessed with the PEG (pain intensity [P], interference with enjoyment of life [E], and interference with general activity [G]) (Krebs et al., 2009), a 3-item measure of average pain intensity and interference in enjoyment and general activity from pain over the past month. Items are rated on a 0-10 scale and averaged to derive a composite scale score. The PEG’s reliability, convergent validity, and sensitivity to change in pain over a six-month period have been demonstrated previously (Krebs et al., 2009). In this study internal consistency was excellent at each wave (Cronbach’s α = .95 to .96).

Stress appraisals were measured with the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Items are rated on a 1-5 scale and summed to derive a composite scale score. Higher ratings indicate greater frequency of appraising life circumstances as stressful and uncontrollable. The reliability and validity of the PSS have been documented in previous research (Cohen et al., 1983). Internal consistency was adequate at each wave (Cronbach’s α = .80 to .84).

At baseline we also assessed sociodemographic and personal characteristics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, highest level of education, immigrant status, years of residence in the U.S., marital status, parental status, health insurance status, comfort speaking English, and self-reported lifetime history of medical conditions and Criterion A physical traumas.

Data Analysis

Longitudinal, reciprocal associations between PTSD, pain, and stress appraisals were estimated across the three waves with cross-lagged regression models (Finkel, 1995). In a cross-lagged regression model, multiple measures at time t are regressed on the same measures at time t-1. Because each variable is regressed on its previous instance, the cross-lagged paths represent the effect of each variable on change in the other variable. All analyses were conducted in the lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) package in R using a robust maximum likelihood estimator, which is robust to violations of normality. This is a full information estimator that uses all available information and provides consistent, unbiased estimates in the presence of data which are missing at random or missing completely at random (Allison, 2001). Sites were included as a fixed effect to control for differences between them.

In preliminary analyses, we evaluated a wide range of potentially confounding variables, including sociodemographic and personal characteristics, time since trauma, interview completion by phone or in-person, and intervention condition. We retained in the final model those variables for which the multivariate effect on pain, PTSD symptoms, or stress appraisals was significant at p < .20, which included ethnicity, immigrant status, and age. Intervention condition did not meet this criterion but was included as a covariate because of its hypothesized importance as a causal influence on PTSD.

Analyses of attrition indicated lower odds of dropout at 6 (OR = 0.96, p < .001) and 12 months (OR = 0.97, p = .031) for each additional year of age and higher odds of dropout for respondents in the intervention vs. control condition (OR = 1.94, p = .018).

Results

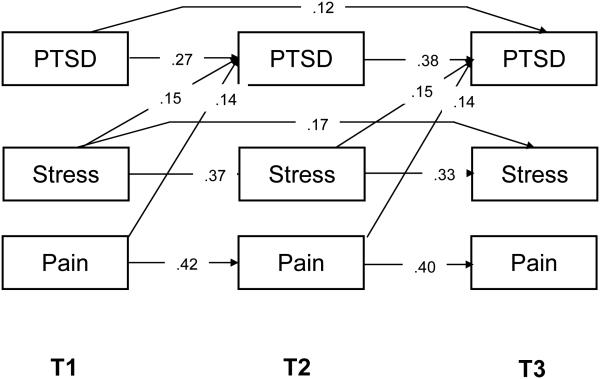

Descriptive statistics for PTSD symptom severity, pain, and stress appraisals at each wave are presented in Table 1. Although the model was rejected, χ2(15, N = 355) = 31, p = .008, other fit indices less influenced by sample size indicated adequate model fit (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = .06). As shown in Figure 1, higher levels of pain and stress appraisals independently predicted increases in PTSD symptoms, with adjustment for covariates. Neither PTSD symptoms nor stress appraisals, however, predicted change in pain.

Table 1.

PTSD Symptom Severity and Diagnosis, Pain, and Stress Appraisals at Three Waves

| Variable | T1 (n = 355) |

T2 (n = 239) |

T3 (n = 267) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M or n | SD or % | M or n | SD or % | M or n | SD or % | |

| PTSD severity | 70.56 | 15.96 | 49.92 | 24.78 | 46.34 | 25.18 |

| Pain | 5.90 | 3.54 | 5.00 | 3.58 | 5.12 | 3.96 |

| Stress appraisals | 46.02 | 8.06 | 46.20 | 8.61 | 45.06 | 10.01 |

|

| ||||||

| PTSD diagnosis | 355 | 100 | 119 | 50.6 | 109 | 41.3 |

Note. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. PTSD symptom severity scores can range from 0-136. Pain scores can range from 0 to 10. Stress appraisals can range from 14 to 70.

Figure 1.

N = 355. Cross-lagged regression model of longitudinal associations between PTSD symptom severity, pain, and stress appraisals. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. All numbers in the figure are standardized regression coefficients estimated with adjustment for ethnicity, immigrant status, age, and study condition. Only coefficients that were statistically significant at p < .05 are shown.

Before conducting formal mediation tests, mediational prerequisites of significant associations between the hypothesized mediator (stress appraisals) and the independent and dependent variables were assessed (MacKinnon, 2008). Stress appraisals at Time 2 were not significantly predicted by pain or PTSD symptoms at Time 1 and, therefore, did not mediate the longitudinal associations between PTSD and pain.

Discussion

This study’s findings dovetailed with previous research demonstrating longitudinal effects of pain on PTSD, but departed from research showing effects of PTSD on pain (Stratton et al., 2014). The lack of bidirectional longitudinal associations between pain and stress appraisals was also unexpected. This might be explained by the small amount of change over time on pain and stress appraisals, which left little variation to be explained by predictors.

Pain and stress appraisals independently predicted increases in PTSD symptoms, but stress appraisals did not mediate the effect of pain on PTSD as hypothesized. Although these nonsignificant mediational findings might be attributable to methodological limitations or characteristics of this particular sample (e.g., small amount of change over time on pain and stress appraisals), it is also possible that stress appraisals simply do not function as a mechanism that underlies the associations between pain and PTSD. Future research should evaluate the role of other mechanisms that have been proposed in current theoretical models (e.g., attentional biases toward trauma- and pain-related cues) as mediators of the longitudinal associations between pain and PTSD.

The current findings were limited by their unclear generalizability to other populations. This study was conducted in a very specific population: All participants met criteria for PTSD at baseline and reported fairly high levels of PTSD symptom severity, as the average level of baseline PTSD symptom severity on the CAPS was slightly higher than that of another sample of trauma-exposed, inner city primary care patients (M = 60.8, SD = 30.0; (Alim et al., 2008). Moreover, it is unclear whether the findings obtained with the CAPS based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria would extend to PTSD patients assessed with the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. In addition, although the average level of baseline pain on the PEG closely resembled that of a sample of primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (M = 6.1, SD = 2.2; (Krebs et al., 2009), it is unknown whether the current findings would generalize to chronic pain patients.

The current study also had several strengths, including the rigorous measurement of PTSD with a gold-standard diagnostic interview (i.e., the CAPS), three waves of longitudinal data for generating unbiased estimates of mediated effects, and the use of path analysis to model the interrelationships among stress appraisals, pain, and PTSD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to Lisa Meredith from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01MH082768).

References

- Alim TN, Feder A, Graves RE, Wang Y, Weaver J, Westphal M, Charney DS. Trauma, resilience, and recovery in a high-risk African-American population. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1566–1575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121939. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, C.A.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Coons MJ, Taylor S, Klatz J. PTSD and the experience of pain: Research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47:903–907. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JG, Clapp JD. A different kind of comorbidity: Understanding posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2011;3:101–108. doi: 10.1037/a0021263. doi:10.1037/a0021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of psychological stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SE. Causal Analysis with Panel Data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Sutherland JM, Kroenke K. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Stein MB. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis: Routledge. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Eisenman DP, Green BL, Kaltman S, Wong EC, Han B, Tobin JN. Design of the Violence and Stress Assessment (ViStA) study: A randomized controlled trial of care management for PTSD among predominantly Latino patients in safety net health centers. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;38:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.005. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: Mutual maintenance? Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:857–877. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00071-4. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton KJ, Clark SL, Hawn SE, Amstadter AB, Cifu DX, Walker WC. Longitudinal interactions of pain and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. military service members following blast exposure. The Journal of Pain. 2014;15:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. doi:10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]