Abstract

Background. Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHF) are a group of systemic diseases characterized by fever and bleeding, which have posed a formidable potential threat to public health with high morbidity and mortality. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) formulas have been acknowledged with striking effects in treatment of hemorrhagic fever syndromes in China's history. Nevertheless, their accurate mechanisms of action are still confusing. Objective. To systematically dissect the mechanisms of action of Chinese medicinal formula Xijiao Dihuang (XJDH) decoction as an effective treatment for VHF. Methods. In this study, a systems pharmacology method integrating absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) screening, drug targeting, network, and pathway analysis was developed. Results. 23 active compounds of XJDH were obtained and 118 VHF-related targets were identified to have interactions with them. Moreover, systematic analysis of drug-target network and the integrated VHF pathway indicate that XJDH probably acts through multiple mechanisms to benefit VHF patients, which can be classified as boosting immune system, restraining inflammatory responses, repairing the vascular system, and blocking virus spread. Conclusions. The integrated systems pharmacology method provides precise probe to illuminate the molecular mechanisms of XJDH for VHF, which will also facilitate the application of traditional medicine in modern medicine.

1. Introduction

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHF) are a group of systemic diseases caused by certain viruses, such as Ebola, Lassa, Dengue, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever viruses. Patients with VHF show the common cardinal symptoms, including fever, hemorrhages, and shock [1]. Data obtained over the past years indicate that these diseases are characterized by intense inflammatory responses with generalized signs of increased vascular permeability, severely impaired immune functions, diffuse vascular dysregulation, and coagulation abnormalities [2, 3]. VHF are generally prevalent in developing countries, which have posed a serious public health threat with high mortality, morbidity, and infectivity in recent years [4]. Currently, many large pharmaceutical companies are pursuing an effective antiviral therapy for VHF. Although the broad-spectra antiviral drug ribavirin is approved for treatment of several types of VHF, there remains a need for a safe and more effective medication to replace the antiviral drug [5].

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) formulas consisting of complex mixtures of multiple plants play an outstanding role in the treatment of various acute infectious diseases because of the pharmacological and pharmacokinetic synergistic effects of the abundant bioactive ingredients [6]. A series of TCM prescriptions for hemorrhagic fever syndromes have been described in history [7, 8]. For example, XJDH is a famous TCM formula for treating hemorrhagic fever syndromes [9]. XJDH originally comes from “Prescriptions Worth A Thousand Gold” which is written by the “Medicinal King” Sun Simiao in the Tang Dynasty (around 700 AD) [10, 11]. The components of the formula include Rhino horn (substituted by Buffalo Horn now, Shui Niujiao in Chinese), Rehmannia dried rhizome (Sheng Dihuang in Chinese), Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (Shao Yao in Chinese), and Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. (Mu Danpi in Chinese). Actually, XJDH has been normally used for cooling the blood for hemostasis, stopping bleeding accompanied with fever, removing toxic substances, and treating the cases of high fever and sweating, spontaneous bleeding, hemoptysis, and nosebleeds [12, 13]. Although the therapeutic efficiency of XJDH in the treatment of VHF is attractive, several fundamental questions are still unclear. What are the potential active ingredients of XJDH? What are the underlying molecular mechanisms of action of the formula in the treatment of VHF? What are the precise targets of these medicines? Since the multiple components-multiple targets interaction model of TCM formulas, traditional experimental research methods show up the shortcomings of long-term investment.

Fortunately, as an emerging discipline, systems pharmacology provides a new way to solve the complex pharmacological problems [14]. Systems pharmacology integrates pharmacokinetic data (ADME/T characteristics of a drug) screening together with targets prediction, networks, and pathways analyses to explore the drug actions from molecular and cellular levels to tissue and organism levels. It also provides an analysis platform for decoding molecular mechanisms of TCM formulas. In our previous work, a series of systems pharmacology methods have been exploited to uncover the underlying mechanisms of action of TCM formulas for cardiovascular diseases, depression, and cancer [15–17].

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms of XJDH in treating VHF based on systems pharmacology method. Firstly, four pharmacokinetic models, including oral bioavailability (OB), drug-likeness (DL), Caco-2 permeability, and drug half-life (HL), were employed to filter out the potential active ingredients with favorable ADME profiles from XJDH. Then, based on an integrated target prediction method which combined the biological and mathematical models, the corresponding targets of these active ingredients were identified. Finally, the network pharmacology and VHF-related signaling pathways analysis was carried out to systematically disclose the underlying interactions between drugs, target proteins, and pathways. The detailed flowchart of the systems pharmacology method is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The detailed flowchart of the systems pharmacology method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Active Compounds Database

All chemicals of these four medicines in XJDH were manually collected from a wide-scale text mining and our in-house developed database: the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP, http://lsp.nwsuaf.edu.cn/tcmsp.php) [18]. In order to obtain the potential active compounds from these medicines, we applied a method incorporating OB, DL, Caco-2 permeability, and drug HL evaluation in this work.

2.1.1. OB Prediction

OB is defined as “the ratio of how many active components absorbed into the circulatory system to play a role at the site of action.” OB is one of the vital pharmacokinetic profiles in active compounds screening processes. In this work, the OB screening was calculated by a robust in-house system, OBioavail1.1 [19], and components with OB ≥ 30% were selected as the candidate molecules for further study. The following two basic sections describe the design principles of the threshold: (1) information from the studied medicines is obtained as much as possible using the least number of compounds and (2) the established model can be elucidated within reason by the reported pharmacological data [6].

2.1.2. DL Prediction

DL generally means “molecule which holds functional groups and/or has physical properties consistent with the majority of known drugs” [20]. In this study, we performed a self-constructed model pre-DL (predicts drug-likeness) based on the molecular descriptors and Tanimoto coefficient [21]. The DL index of the compounds was calculated by Tanimoto coefficient defined as

| (1) |

where A is the molecular descriptors of herbal compounds, B represents the average molecular properties of all compounds in DrugBank database (http://www.drugbank.ca/) [22]. The DL ≥ 0.18 (average value for DrugBank) was defined as the criterion to select those drug-like compounds which are chemically suitable for drugs.

2.1.3. Caco-2 Permeability Prediction

The majority of orally administered drugs absorption occurs in the small intestine where the surface absorptivity greatly improves with the presence of villi and microvilli [23]. Previously, researchers have developed a quantity of in silico drug absorption models using in vitro Caco-2 permeability in drug discovery and development processes [24]. In this study, based on 100 drug molecules with satisfactory statistical results, a robust in silico Caco-2 permeability prediction model pre-Caco-2 (predicts Caco-2 permeability) was employed to predict the compound's intestinal absorption [25]. Finally, on the account of the fact that compounds with Caco-2 value less than 0 are not permeable, in the study, the threshold of Caco-2 permeability was set to 0.

2.1.4. Drug HL Prediction

An in silico pre-HL (predicts half-life) has been developed in our previous work to calculate the drug HL by using the C-partial least square (C-PLS) algorithm which is supported by 169 drugs with known half-life values [26–28]. HL evaluates the time needed for compounds in the body to fall by half, and components with long HL were selected as the candidate molecules.

In order to obtain the potential active ingredients, the screening principle was defined as follows: OB ≥ 30%; Caco-2 ≥ 0; DL ≥ 0.18; or long HL.

2.2. Drug Targeting

Apart from screening out the active compounds, the therapeutic targets exploration is also a vital stage. Firstly, the potential targets exploration was fulfilled based on the systematic drug targeting tool (SysDT) as described in our previous work. Based on two mathematical tools, Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), the method can comprehensively ascertain the compound-target interaction profiles [29]. These two models exert great property of predicting the drug-target mutual effects with a concordance of 82.83%, a sensitivity of 81.33%, and a specificity of 93.62%. In this work, the compound-target interactions with SVM score ≥ 0.8 and the RF score ≥ 0.7 were selected for further research. Secondly, a recently developed computational model named weighted ensemble similarity (WES) was also introduced to detect drug direct targets [30]. For internal validation, this model performed remarkably well in predicting the binding (average sensitivity 72%, SEN) and the nonbinding (average specificity 82%, SPE) patterns, with the average areas under the receiver operating curves (ROC, AUC) of 85.2% and an average concordance of 77.5%. Thirdly, the obtained protein targets were mapped to the database UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/) for normalization [31]. Finally, in order to identify and analyze the specific biological properties of the potential targets, the Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes were introduced to dissect target genes in a hierarchically structured way based on biological terms [32]. The GlueGO, a Cytoscape plug-in, was utilized to interpret the biology processes of large lists of genes.

2.3. Network Construction and Analysis

In order to explore the multiple mechanisms of action of XJDH for VHF, currently we analyzed the relationship between candidate compounds and potential targets by constructing the drug-target network (D-T network), in which all active compounds are connected to their targets. The network was generated by Cytoscape 2.8.1 [33]. In the network, compounds and targets are represented by nodes, while the interactions between them are represented by edges. In addition, a vital topological parameter, namely, degree was analyzed by the plugin NetworkAnalyzer of Cytoscape [34]. The degree of a node is defined as the number of edges connected to the node.

2.4. Pathway Construction and Analysis

At the pathway level, in order to probe into the action mechanisms of the formula for VHF, an incorporated “VHF pathway” was established based on the current knowledge of VHF pathology. Firstly, the obtained human target proteins were collected to be input into the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.kegg.jp/) database to acquire the information of pathways. Then, based on the obtained information of basic pathways, we assembled an incorporated “VHF pathway” by picking out closely linked pathways related with VHF pathology.

3. Results

3.1. Active Compounds Screening

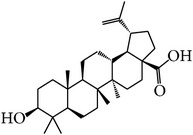

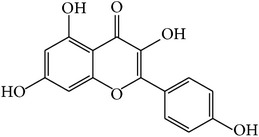

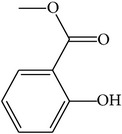

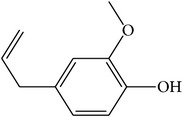

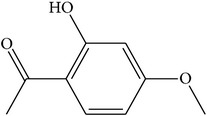

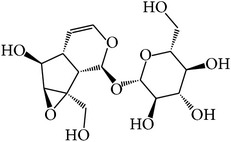

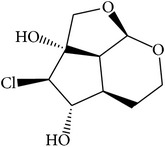

We employed four ADME parameters to screen out the potential active components of XJDH. As a result, from the 136 compounds of XJDH (as shown in supporting information, Table S1, in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/9025036), a total of 20 active compounds pass through the criteria of OB ≥ 30%, Caco-2 ≥ 0, DL ≥ 0.18, or long HL. Besides, in order to obtain a more accurate result, some certain rejected compounds, which have relatively poor pharmacokinetic properties, but are the most abundant and active ingredients of certain herbs, were also selected as the active components for further research. For example, although catalpol (MOL108) has poor OB, Caco-2, and HL properties, it has been reported to be rich in the roots of Rehmannia dried rhizome. And rehmaglutin D (MOL116) and paeoniflorin (MOL046) with poor OB (14.43%) take a large proportion in Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Thus, the three compounds were also retained for further analysis. Finally, a total of 23 active ingredients were obtained in this study (as shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

23 potential compounds of XJDH and their network parameters.

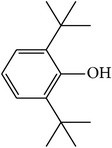

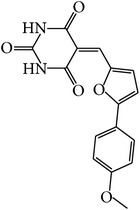

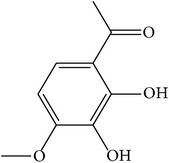

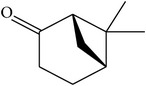

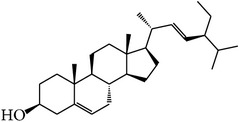

| MOL_ID | Compounds | Structure | OB | Caco-2 | DL | HL | Degree | Medicines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOL001 | Cholesterol |

|

37.87 | 1.31 | 0.68 | Long | 16 | Buffalo Horn |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL004 | 2,2-Dimethylcyclohexanol |

|

82.54 | 1.22 | 0.02 | Long | 12 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL005 | Dibutylphenol |

|

38.90 | 1.73 | 0.06 | Long | 15 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL006 | Methyl gallate |

|

30.91 | 0.26 | 0.05 | Long | 17 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

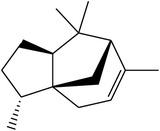

| MOL014 | (−)-Alpha-cedrene |

|

55.56 | 1.81 | 0.10 | Long | 16 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

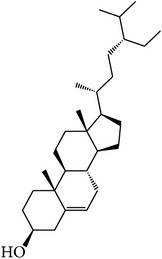

| MOL018 | β-Sitosterol |

|

36.91 | 1.34 | 0.75 | Short | 21 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Paeonia suffruticosa Andr., Rehmannia dried rhizome |

|

| ||||||||

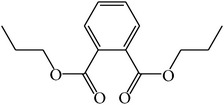

| MOL025 | Dipropyl Phthalate |

|

66.30 | 0.78 | 0.10 | Long | 8 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL031 | Mairin |

|

55.38 | 0.73 | 0.78 | Short | 14 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

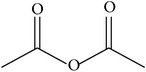

| MOL041 | Acetyl oxide |

|

45.13 | 0.65 | 0 | Long | 12 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

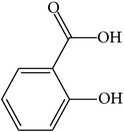

| MOL045 | Salicylic acid |

|

32.13 | 0.63 | 0.027 | Long | 19 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL046 | Paeoniflorin |

|

14.43 | −1.38 | 0.79 | Short | 5 | Paeonia lactiflora Pall. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL053 | Apocynin |

|

31.71 | 0.74 | 0.04 | Long | 22 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL060 | Kaempferol |

|

69.61 | 0.15 | 0.24 | Long | 41 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL066 | Methyl salicylate |

|

42.55 | 1.05 | 0.03 | Long | 17 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL070 | Eugenol |

|

44.47 | 1.36 | 0.04 | Long | 34 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

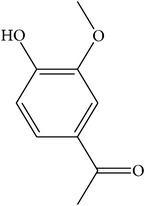

| MOL072 | Paeonol |

|

30.98 | 0.91 | 0.04 | Long | 27 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL073 | 5-[[5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-furyl]methylene]barbituric acid |

|

43.44 | 0.09 | 0.30 | Long | 10 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL075 | 1-(2,3-Dihydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethanone |

|

32.96 | 0.81 | 0.05 | Long | 25 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL077 | Vanillic acid |

|

35.47 | 0.43 | 0.04 | Long | 13 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL078 | (1R)-(+)-Nopinone |

|

57.86 | 1.23 | 0.05 | Long | 7 | Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL096 | Stigmasterol |

|

43.83 | 1.44 | 0.76 | Short | 18 | Rehmannia dried rhizome |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL108 | Catalpol |

|

14.78 | −2.10 | 0.44 | Short | 6 | Rehmannia dried rhizome |

|

| ||||||||

| MOL116 | Rehmaglutin D |

|

62.9 | −0.31 | 0.1 | Long | 7 | Rehmannia dried rhizome |

For all these 23 ingredients, many of them have been reported to demonstrate significant biologic activity including anti-inflammatory, antivirus, antipyretic, and immune-regulatory activities and protection effect of vascular endothelial cell. For instance, methyl gallate (MOL006, OB = 30.91%, Caco-2 = 0.26, and long HL), obtained from Paeonia lactiflora Pall., shows antivirus activity by interacting with virus proteins and altering the adsorption and penetration of the virion [35]. Salicylic acid (MOL045, OB = 32.13%, Caco-2 = 0.63, and long HL) and paeoniflorin (MOL046) with poor OB from Paeonia lactiflora Pall. exhibit antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, and immune-regulatory activities [36, 37]. In addition, kaempferol (MOL060, OB = 69.61%, Caco-2 = 0.15, DL = 0.24, and long HL), paeonol (MOL072, OB = 30.98%, Caco-2 = 0.91, long HL), and eugenol (MOL070, OB = 44.47%, Caco-2 = 1.36, and long HL), the main active compounds of the radix of Paeonia suffruticosa Andr., have been reported to have potential therapeutic effect for inflammation and vascular injury disorders [38–40]. Besides, it is worth noting that β-sitosterol (MOL018, OB = 36.9%, DL = 0.75) is a common ingredient of Rehmannia dried rhizome, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., and Paeonia suffruticosa Andr., indicating that these active compounds may show synergetic pharmacological effects on VHF.

3.2. Drug Targeting and Functional Analysis

Traditional information retrieval approaches of therapeutic targets of drugs are expatiatory and complicated [41]. To overcome this barrier, we introduced our previous developed target prediction model [29, 30] to dissect interactions between drugs and proteins. As a result, 23 candidate compounds are linked with 118 candidate targets (as shown in Table 2). The results show that many components simultaneously can act on more than one target and many targets can connect to all of the four medicines, demonstrating the promiscuous actions and analogous pharmacological effects of the bioactive molecules. For instance, kaempferol (MOL060) not only serves as the restrainer of Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 [42] but also acts as the inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor [43]. And β-sitosterol (MOL018), which is shared by Rehmannia dried rhizome, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., and Paeonia suffruticosa Andr., acts as the activator of estrogen receptor [44] and transcription factor AP-1 [45]. Meanwhile, the results show that different drugs in XJDH can immediately impact on the common targets such as DNA ligase 1 (LIG1), indicating the synergism or cumulative effects of the drug molecules.

Table 2.

The VHF-related targets information.

| UniProt ID | Name | Gene name | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| O14920 | Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta | IKBKB | Homo sapiens |

| P19320 | Vascular cell adhesion protein 1 | VCAM1 | Homo sapiens |

| P31749 | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase | AKT1 | Homo sapiens |

| P19838 | Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p105 subunit | NFKB1 | Homo sapiens |

| P25963 | NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha | NFKBIA | Homo sapiens |

| A1L156 | LTB4R2 protein | LTB4R2 | Homo sapiens |

| F1D8P7 | Liver X nuclear receptor beta | NR1H2 | Homo sapiens |

| O00748 | Cocaine esterase | CES2 | Homo sapiens |

| O14757 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk1 | CHEK1 | Homo sapiens |

| O15528 | 25-Hydroxyvitamin D-1 alpha hydroxylase, mitochondrial | CYP27B1 | Homo sapiens |

| O43570 | Carbonic anhydrase 12 | CA12 | Homo sapiens |

| O60218 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 | AKR1B10 | Homo sapiens |

| O95622 | Adenylate cyclase type 5 | ADCY5 | Homo sapiens |

| P00325 | Alcohol dehydrogenase 1B | ADH1B | Homo sapiens |

| P00734 | Prothrombin | F2 | Homo sapiens |

| P00797 | Renin | REN | Homo sapiens |

| P00915 | Carbonic anhydrase 1 | CA1 | Homo sapiens |

| P00918 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | Homo sapiens |

| P03372 | Estrogen receptor | ESR1 | Homo sapiens |

| P04150 | Glucocorticoid receptor | NR3C1 | Homo sapiens |

| P04798 | Cytochrome P450 1A1 | CYP1A1 | Homo sapiens |

| P05067 | Amyloid beta A4 protein | APP | Homo sapiens |

| P05091 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | ALDH2 | Homo sapiens |

| P05093 | Steroid 17-alpha-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase | CYP17A1 | Homo sapiens |

| P05177 | Cytochrome P450 1A2 | CYP1A2 | Homo sapiens |

| P06276 | Cholinesterase | BCHE | Homo sapiens |

| P06746 | DNA polymerase beta | POLB | Homo sapiens |

| P07550 | Beta-2 adrenergic receptor | ADRB2 | Homo sapiens |

| P07686 | Beta-hexosaminidase subunit beta | HEXB | Homo sapiens |

| P07900 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | Homo sapiens |

| P08172 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M2 | CHRM2 | Homo sapiens |

| P08183 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 | ABCB1 | Homo sapiens |

| P08235 | Mineralocorticoid receptor | NR3C2 | Homo sapiens |

| P08588 | Beta-1 adrenergic receptor | ADRB1 | Homo sapiens |

| P08913 | Alpha-2A adrenergic receptor | ADRA2A | Homo sapiens |

| P09917 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase | ALOX5 | Homo sapiens |

| P10253 | Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase | GAA | Homo sapiens |

| P10275 | Androgen receptor | AR | Homo sapiens |

| P10636 | Microtubule-associated protein tau | MAPT | Homo sapiens |

| P11229 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M1 | CHRM1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11309 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase pim-1 | PIM1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11413 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | G6PD | Homo sapiens |

| P11413 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | G6PD | Homo sapiens |

| P11473 | Vitamin D3 receptor | VDR | Homo sapiens |

| P11509 | Cytochrome P450 2A6 | CYP2A6 | Homo sapiens |

| P11712 | Cytochrome P450 2C9 | CYP2C9 | Homo sapiens |

| P12931 | Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src | SRC | Homo sapiens |

| P14222 | Perforin-1 | PRF1 | Homo sapiens |

| P14867 | Gamma-aminobutyric-acid receptor subunit alpha-1 | GABRA1 | Homo sapiens |

| P15121 | Aldose reductase | AKR1B1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16152 | Carbonyl reductase [NADPH] 1 | CBR1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16278 | Beta-galactosidase | GLB1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16662 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 | UGT2B7 | Homo sapiens |

| P17538 | Chymotrypsinogen B | CTRB1 | Homo sapiens |

| P18031 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 1 | PTPN1 | Homo sapiens |

| P18089 | Alpha-2B adrenergic receptor | ADRA2B | Homo sapiens |

| P18825 | Alpha-2C adrenergic receptor | ADRA2C | Homo sapiens |

| P18858 | DNA ligase 1 | LIG1 | Homo sapiens |

| P19438 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A | TNFRSF1A | Homo sapiens |

| P19801 | Amiloride-sensitive amine oxidase [copper-containing] | AOC1 | Homo sapiens |

| P20248 | Cyclin-A2 | CCNA2 | Homo sapiens |

| P20309 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 | CHRM3 | Homo sapiens |

| P21397 | Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] A | MAOA | Homo sapiens |

| P21728 | D(1A) dopamine receptor | DRD1 | Homo sapiens |

| P22303 | Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE | Homo sapiens |

| P23219 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 | PTGS1 | Homo sapiens |

| P23368 | NAD-dependent malic enzyme, mitochondrial | ME2 | Homo sapiens |

| P23945 | Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor | FSHR | Homo sapiens |

| P23975 | Sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter | SLC6A2 | Homo sapiens |

| P24941 | Cell division protein kinase 2 | CDK2 | Homo sapiens |

| P25100 | Alpha-1D adrenergic receptor | ADRA1D | Homo sapiens |

| P27338 | Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] B | MAOB | Homo sapiens |

| P27487 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 | DPP4 | Homo sapiens |

| P28223 | 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2A receptor | HTR2A | Homo sapiens |

| P29474 | Nitric oxide synthase, endothelial | NOS3 | Homo sapiens |

| P29475 | Nitric oxide synthase, brain | NOS1 | Homo sapiens |

| P31350 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit M2 | RRM2 | Homo sapiens |

| P33527 | Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 | ABCC1 | Homo sapiens |

| P35228 | Nitric oxide synthase, inducible | NOS2 | Homo sapiens |

| P35348 | Alpha-1A adrenergic receptor | ADRA1A | Homo sapiens |

| P35354 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | PTGS2 | Homo sapiens |

| P35869 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor | AHR | Homo sapiens |

| P36888 | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein kinase FLT3 | FLT3 | Homo sapiens |

| P37231 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | Homo sapiens |

| P43681 | Neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha-4 | CHRNA4 | Homo sapiens |

| P47989 | Xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase [includes xanthine dehydrogenase] | XDH | Homo sapiens |

| P48736 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma isoform | PIK3CG | Homo sapiens |

| P49841 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | GSK3B | Homo sapiens |

| P51684 | C-C chemokine receptor type 6 | CCR6 | Homo sapiens |

| P51843 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 1 | NR0B1 | Homo sapiens |

| P53634 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 1 | CTSC | Homo sapiens |

| P60174 | Triose-phosphate isomerase | TPI1 | Homo sapiens |

| P80365 | Corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 2 | HSD11B2 | Homo sapiens |

| P80404 | 4-Aminobutyrate aminotransferase, mitochondrial | ABAT | Homo sapiens |

| P84022 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 | SMAD3 | Homo sapiens |

| Q00534 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 | CDK6 | Homo sapiens |

| Q04760 | Lactoylglutathione lyase | GLO1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q07075 | Glutamyl aminopeptidase | ENPEP | Homo sapiens |

| Q07973 | 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) 24-hydroxylase, mitochondrial | CYP24A1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q12791 | Calcium-activated potassium channel subunit alpha-1 | KCNMA1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q12882 | Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase [NADP(+)] | DPYD | Homo sapiens |

| Q13822 | Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family member 2 | ENPP2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q13887 | Krüppel-like factor 5 | KLF5 | Homo sapiens |

| Q14524 | Sodium channel protein type 5 subunit alpha | SCN5A | Homo sapiens |

| Q14973 | Sodium/bile acid cotransporter | SLC10A1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q16539 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | MAPK14 | Homo sapiens |

| Q16602 | Calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor | CALCRL | Homo sapiens |

| Q16678 | Cytochrome P450 1B1 | CYP1B1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q16853 | Membrane primary amine oxidase | AOC3 | Homo sapiens |

| Q92731 | Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q96IY4 | Carboxypeptidase B2 | CPB2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9H5J4 | Elongation of very long chain fatty acids protein 6 | ELOVL6 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9HBH1 | Peptide deformylase, mitochondrial | Homo sapiens | |

| Q9NPH5 | NADPH oxidase 4 | NOX4 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9NYA1 | Sphingosine kinase 1 | SPHK1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9UBM7 | 7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase | DHCR7 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9UNQ0 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 | ABCG2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9Y263 | Phospholipase A-2-activating protein | PLAA | Homo sapiens |

| Q9Y2I1 | Nischarin | NISCH | Homo sapiens |

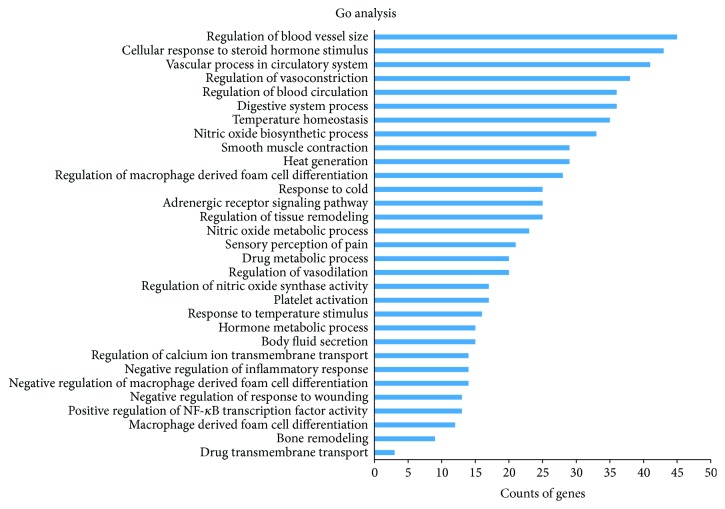

In general, vascular system, particularly the endothelium, plays a key role in VHF development [3]. A strong inflammatory response characterized by high circulating concentrations of cytokines and chemokines occurs early during the VHF infectious process [46]. And the patients' immune functions might also be severely impaired; innate defenses are further hindered by the loss of natural killer cells [47]. The relevant biological processes of above targets were revealed by GlueGO (as shown in supporting information, Table S2). Figure 2 provides primary biological processes of these targets by cluster analysis. It is interesting to note that these targets are involved in a variety of biological processes including regulation of macrophage derived from cell differentiation, regulation of vasoconstriction and vasodilation, nitric oxide biosynthetic process, and vascular process in circulatory system. These biological processes largely fall into three groups: controlling inflammation response, modulating the immune system, and accommodation of vascular system. For example, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A (TNFRSF1A), beta-2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2), and so forth are involved in the regulation of acute inflammatory response. Nitric oxide synthase, inducible (NOS2), dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), and so forth are associated with regulation of immune effector process, while nitric oxide synthase, endothelial (NOS3), NOS2, Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5), and so forth are directly connected to blood vessel remodeling and blood vessel morphogenesis. These suggest that XJDH might exert the therapeutic effect on VHF mainly through anti-inflammation, enhancing immunity and vascular repair therapy.

Figure 2.

ClueGO analysis of the potential targets. y-axis shows significantly enriched “biological process” (BP) categories in GO relative to the target genes, and x-axis shows the counts of targets.

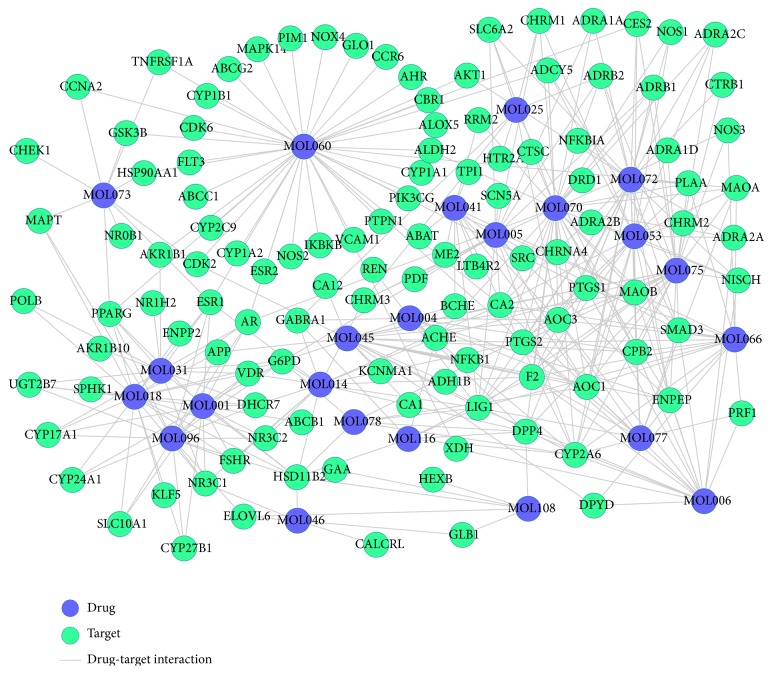

3.3. Drug-Target Network Construction and Analysis

As shown in Figure 3, D-T network is constructed including 141 nodes (23 active compounds and 118 potential targets) and 382 edges. The degrees of the candidate compounds are shown in Table 1; this provides us with an intuitionistic concept to distinguish those highly connected vital compounds or targets from the others in the network. The results of network analysis show that 18 out of 23 candidate compounds are linked with more than ten targets, among which kaempferol (MOL060) displays the highest number of target interactions (degree = 41), followed by eugenol (MOL070, degree = 34) and paeonol (MOL072, degree = 27). This confirms the multitarget properties of herbal compounds. We speculate that the top three ingredients might be the crucial elements in the treatment of VHF. For instance, kaempferol (MOL060) is predicted to interact with 41 targets like calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor (MAPK14), PPARγ, and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma isoform (PIK3CG). MAPK14 takes part in the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) synthesis through the mediation of angiotensin II [48]. VEGF can induce angiogenesis and improve the increased vascular permeability, so as to prevent bleeding in patients with VHF [49]. Besides, kaempferol is also found to significantly upregulate the transcriptional activity of PPARγ, which acts as an inhibitor of inflammatory gene expression and vandalizes proinflammatory transcription factor signaling pathways in vascular cells [50]. Additionally, previous finding suggests that PIK3CG interacting with kaempferol can participate in inflammation processes and influence the innate immune system [51]. Thus, these key active ingredients of XJDH work mainly by modulating inflammatory factor, innate immune system, and VEGF.

Figure 3.

D-T network. The blue circles represent candidate compounds in XJDH, while the green circles represent target proteins, and each edge represents the interaction between them.

Meanwhile, the results also show that one target can be hit by multiple compounds from different medicines, indicating synergism or summation effects of the formula. According to the D-T network analysis, 64 out of the 118 targets have at least two links with the components of different herbs. XJDH exerts its therapeutic effect for VHF by binding and regulating particular protein targets. For instance, prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 (PTGS2) is simultaneously targeted by 10 active compounds including eugenol (MOL070, from Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.), paeonol (MOL072, from Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.), and salicylic acid (MOL045, from Paeonia lactiflora Pall.). PTGS2 is possibly an effective marker of platelet dysfunction; a reduced PTGS2 expression in the VHF primate model cells could directly result in platelet dysfunction [52]. Fortunately, in agreement with our study, previous findings suggest that eugenol and paeonol can control the expression of PTGS2 through the suppression of NF-κB in macrophage [53–55], so as to recover the function of thrombocyte. Study shows that severe disseminated intravascular coagulation is the mechanisms of bleeding in all VHF [3]. Prothrombin (F2), the precursor substances of clotting enzyme, plays a crucial role in optimizing the procoagulant activity through controlling the anticoagulant function of meizothrombin [56]. Thus, these 10 ingredients such as methyl gallate (MOL006, from Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), salicylic acid (MOL045, from Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), and apocynin (MOL053, Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) interacting with F2 may be the key factors in the treatment of bleeding in patients with VHF. By analyzing the above D-T network, we can conclude that XJDH produces the healing efficacy for VHF probably by three different ways, intervening in the process of inflammation, boosting immune reaction, and repairing vascular system.

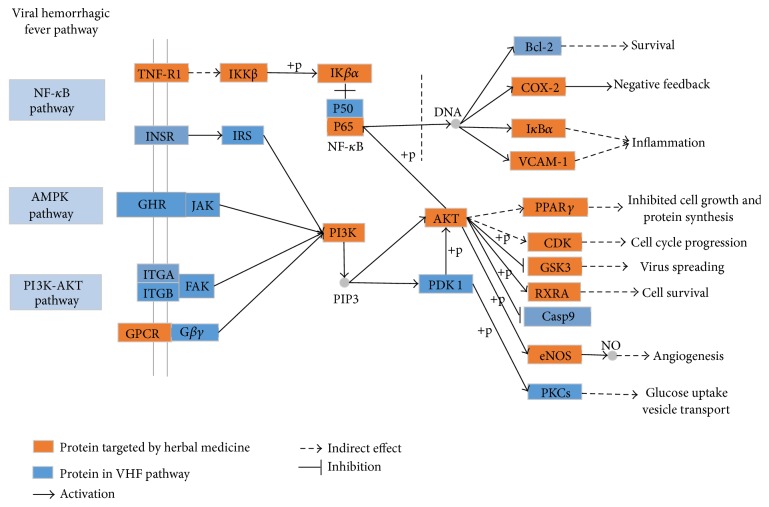

3.4. Pathway Analysis

To explore the integral regulation of XJDH for the treatment of VHF, we assembled an integrated “VHF pathway” (Figure 4) on the basis of the current knowledge of VHF pathogenesis. By means of inputting the obtained human target proteins into KEGG pathway database, result shows that 110 of the 118 targets can be mapped to the KEGG pathways, including NF-κB signaling pathway, AMPK pathway, and PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Now, three detailed therapeutic modules are provided (inflammation module, angiogenesis module, and virus spreading module).

Figure 4.

The VHF pathway and therapeutic modules.

3.4.1. Inflammation Module

As shown in Figure 4, 7 key proteins targeted by XJDH are mapped onto a key inflammation process, namely, NF-κB signaling pathway, indicating the anti-inflammatory action may play a vital role in the treatment of VHF. Patients with VHF have a strong inflammatory response with high inflammatory cytokines and chemokines levels such as IL-1β, TNF, and IL-6 in the early phase of VHF [46]. The expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) is mediated by NF-κB [57], and NF-κB is one of the most important regulators of proinflammatory gene expression. The result demonstrates that paeoniflorin (MOL046) from Paeonia lactiflora Pall. and Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. can regulate transcription factor NF-κB activity. Meanwhile, other researchers have verified that paeoniflorin can restrain the activation of the NF-κB pathway via inhibiting IκB kinase [58]. In addition, vascular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), a cell adhesion molecule, also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and immune processes [59]. Our work indicates that kaempferol (MOL060) and β-sitosterol (MOL018) can regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines by targeting vascular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1). Consequently, the foregoing analysis shows that XJDH has the effect of ameliorating the symptoms of inflammation disorders of patients with VHF.

3.4.2. Virus Spreading Module

In Figure 4, the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) pathway is a significant cell signaling pathway that regulates diverse cellular activities including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and vesicular trafficking. Notably, our research shows that, in line with previous studies, kaempferol (MOL060) is predicted to modulate PI3Ks activity, and AKT is also a target for kaempferol (MOL060) and paeonol (MOL072) [60–62]. Besides, PI3Ks, a family of lipid kinases, can prevent hemorrhagic fever virus entry into host cells by regulating cellular activities of vesicular trafficking [63]. AKT is a major downstream effector of the PI3K pathway, and this target protein can control the expression of many molecules directly or indirectly. Moreover, evidence also suggests that activity of PI3K/Akt pathway is required for hemorrhagic fever virus intruding into the host cells [63]. Therefore, depressors of PI3K and AKT dramatically reduced the risk of hemorrhagic fever virus infection at an early step during the replication cycle. These above analyses show that XJDH could make effective control of hemorrhagic fever virus entry into cells, thus blocking virus spread by interfering with the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway.

3.4.3. Angiogenesis Module

VHF is a severe multisystem syndrome characterized by diffuse vascular damage. The vascular system, particularly the vascular endothelium, seems to be directly and indirectly targeted by hemorrhagic fever viruses [3]. In the VHF pathway shown in Figure 4, PI3K pathway and AMPK pathway are involved in regulating the angiogenesis progress. We find out that apocynin (MOL053), kaempferol (MOL060), methyl salicylate (MOL066), and eugenol (MOL070) can affect the activity of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and then bring about NO production changes in endothelial cell. Moreover, at present, a large number of researches indicate that the synthesis of bioactive endothelium-derived NO is required for the progress of angiogenesis [64–66]. Therefore, the evidence presented enables us to reasonably conclude that the XJDH takes part in regulation of angiogenesis progress through PI3K signaling pathway and AMPK pathway.

4. Discussion

Actually, XJDH has been normally used for cooling the blood for hemostasis, stopping bleeding accompanied with fever, removing toxic substances, and treating the cases of high fever and sweating, spontaneous bleeding, hemoptysis, and nosebleeds [13, 67]. Although XJDH has been used historically for treating hemorrhagic fever syndromes, the specific bioactive molecules responsible for VHF and their precise mechanisms of action are still unclear. Thus, in this work, a systems pharmacology method combining the screening active components, drug targeting, network, and pathway analysis was carried out, so as to uncover the active ingredients, targets, and pathways of XJDH and systematically decipher its therapeutic mechanism of actions.

Our results show that 23 active ingredients were obtained from XJDH, and 118 potential targets were predicted. These manifest that the characteristics of XJDH are multicomponent botanical therapeutics and multitargets synergetic therapeutic effects. The GO analysis of targets and integrated D-T network analysis demonstrate the synergistic effects of XJDH for the treatment of VHF mainly through boosting of immune system, inhibiting inflammatory response, and repairing vascular system. Meanwhile, the integrated “VHF pathway” analysis in our work shows that XJDH might simultaneously regulate multitargets/pathways coupled with a range of therapeutic modules, for example, anti-inflammation, antivirus, and angiogenesis.

Now most researchers believe that VHF can be attributed to the simultaneous occurrence of multiple pathogenic mechanisms. They are mainly as follows: hemorrhagic fever virus infection stimulates macrophages to release cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators, causing fever, malaise, alterations in vascular function, and a shift in the coagulation system toward a procoagulant state, and immune functions might also be severely impaired [2]. Besides, hemorrhagic fever virus can target the vascular system directly and indirectly and cause endothelial activation and dysfunction [3]. In this study, we show here for the first time using GO enrichment analysis, network analysis, and integrated pathway analysis that XJDH significantly enriches target genes involved in reducing the inflammation response, enhancing immunity, combating the spreading virus, and preventing vascular dysfunction. And more experiments are needed to verify the validity of the results in further research works.

5. Conclusions

The result of this study provides bioactive ingredients, vital targets, and pathways of XJDH. We have come to the conclusion that the action mechanisms of XJDH for VHF mainly include restoring the immune system and enhancing immune response, ameliorating the symptoms of inflammation disorders, improving their vascular endothelial dysfunction, and combating the spreading virus. The systems pharmacology method established in our work provides preliminary clues that the multilayer networks of drug-target paradigm may be valuable for the modernization of TCM formulas at molecular level and then push forward their acceptance into mainstream medicine.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: the 136 compounds information of XJDH.

Table S2: the relevant biological processes of the candidate targets.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants from Northwest A&F University, National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170796 and 81373892), and Science and Technology Department of Shaanxi Province, Natural Science Fund Projects (2014JM3063). It was also supported in part by China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (ZZ0608).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests with respect to this study.

Authors' Contributions

Jianling Liu and Tianli Pei contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Jahrling P. B., Marty A. M., Geisbert T. W. Medical Aspects of Biological Warfare. Washington, DC, USA: Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army, and Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2007. Viral hemorrhagic fevers; pp. 271–310. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray M. Pathogenesis of viral hemorrhagic fever. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2005;17(4):399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnittler H.-J., Feldmann H. Viral hemorrhagic fever-a vascular disease? Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2003;89(6):967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borio L., Inglesby T., Peters C. J., et al. Hemorrhagic fever viruses as biological weapons: medical and public health management. JAMA. 2002;287(18):2391–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray M. Highly pathogenic RNA viral infections: challenges for antiviral research. Antiviral Research. 2008;78(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X., Xu X., Li Y., et al. Systems pharmacology uncovers Janus functions of botanical drugs: activation of host defense system and inhibition of influenza virus replication. Integrative Biology. 2013;5(2):351–371. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20204b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Y.-P., Woerdenbag H. J. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Pharmacy World and Science. 1995;17(4):103–112. doi: 10.1007/bf01872386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yina Z.-A., He Y.-Y., Long L., et al. Prevention and treatment idea of Chinese medicine on ebola hemorrhagic fever. Journal of Acupuncture and Herbs. 2014;2(2014):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharmananda S. Treatment of leukemia using integrated Chinese and western medicine. International Journal of Oriental Medicine. 1997;22:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai J., Zhen Y. Medicine Across Cultures. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2003. Medicine in ancient China; pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dharmananda S. Sun Simiao. Vol. 1. Deutsche Übersetzung in ZTCM; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jing S., Xiaojiang Z. Professor Zhang Shiqing's experience on treating pediatric allergic purpura with Xijiao Dihuang decoction. Journal of Gansu College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2005;3, article 3 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng B.-R., Shen J.-P., Zhuang H.-F., Lin S.-Y., Shen Y.-P., Zhou Y.-H. Treatment of severe aplastic anemia by immunosuppressor anti-lymphocyte globulin/anti-thymus globulin as the chief medicine in combination with Chinese drugs. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2009;15(2):145–148. doi: 10.1007/s11655-009-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger S. I., Iyengar R. Network analyses in systems pharmacology. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(19):2466–2472. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang C., Zheng C., Li Y., Wang Y., Lu A., Yang L. Systems pharmacology in drug discovery and therapeutic insight for herbal medicines. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2013;15(5):710–733. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt035.bbt035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X., Xu X., Wang J., et al. A system-level investigation into the mechanisms of Chinese traditional medicine: compound danshen formula for cardiovascular disease treatment. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043918.e43918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao W., Xu X., Wang X., et al. Network pharmacology-based prediction of the active ingredients and potential targets of Chinese herbal Radix Curcumae formula for application to cardiovascular disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;145(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. Journal of Cheminformatics. 2014;6(1, article 13) doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X., Zhang W., Huang C., et al. A novel chemometric method for the prediction of human oral bioavailability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13(6):6964–6982. doi: 10.3390/ijms13066964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters W. P., Murcko M. A. Prediction of ‘drug-likeness’. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54(3):255–271. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H., Wang J., Zhou W., Wang Y., Yang L. Systems approaches and polypharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines: an example using licorice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;146(3):773–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wishart D. S., Knox C., Guo A. C., et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(supplement 1):D668–D672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pang K. S. Modeling of intestinal drug absorption: roles of transporters and metabolic enzymes (for the gillette review series) Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2003;31(12):1507–1519. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.12.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kam A., Li K. M., Razmovski-Naumovski V., et al. The protective effects of natural products on blood-brain barrier breakdown. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;19(12):1830–1845. doi: 10.2174/092986712800099794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L., Li Y., Wang Y., Zhang S., Yang L. Prediction of human intestinal absorption based on molecular indices. Journal of Molecular Science. 2007;23:286–291. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulesteix A.-L. PLS dimension reduction for classification with microarray data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2004;3(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung D., Keles S. Sparse partial least squares classification for high dimensional data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2010;9(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knox C., Law V., Jewison T., et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(supplement 1):D1035–D1041. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu H., Chen J., Xu X., et al. A systematic prediction of multiple drug-target interactions from chemical, genomic, and pharmacological data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037608.e37608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng C., Guo Z., Huang C., et al. Large-scale direct targeting for drug repositioning and discovery. Scientific Reports. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C. H., Apweiler R., Bairoch A., et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt): an expanding universe of protein information. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(supplement 1):D187–D191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smoot M. E., Ono K., Ruscheinski J., Wang P.-L., Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(3):431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675.btq675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kane C. J. M., Menna J. H., Sung C.-C., Yeh Y.-C. Methyl gallate, methyl-3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate, is a potent and highly specific inhibitor of herpes simplex virus in vitro. II. Antiviral activity of methyl gallate and its derivatives. Bioscience Reports. 1988;8(1):95–102. doi: 10.1007/bf01128976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grosser T., Smyth E., FitzGerald G. Antiinflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic agents. In: Bruton L., Chabner B. A., Knollmann B. C., editors. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill Education; 2011. p. p. 985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X.-X., Qi X.-M., Zhang W., et al. Effects of total glucosides of paeony on immune regulatory toll-like receptors TLR2 and 4 in the kidney from diabetic rats. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(6):815–823. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan L. L., Dai M. Paeonol from Paeonia suffruticosa prevents TNF-α-induced monocytic cell adhesion to rat aortic endothelial cells by suppression of VCAM-1 expression. Phytomedicine. 2009;16(11):1027–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prakash P., Gupta N. Therapeutic uses of Ocimum sanctum Linn (Tulsi) with a note on eugenol and its pharmacological actions: a short review. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2005;49(2):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markowitz K., Moynihan M., Liu M., Kim S. Biologic properties of eugenol and zinc oxide-eugenol: a clinically oriented review. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology. 1992;73(6):729–737. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90020-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomenick B., Olsen R. W., Huang J. Identification of direct protein targets of small molecules. ACS Chemical Biology. 2010;6(1):34–46. doi: 10.1021/cb100294v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee K. M., Lee K. W., Jung S. K., et al. Kaempferol inhibits UVB-induced COX-2 expression by suppressing Src kinase activity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2010;80(12):2042–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pang J. L., Ricupero D. A., Huang S., et al. Differential activity of kaempferol and quercetin in attenuating tumor necrosis factor receptor family signaling in bone cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;71(6):818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi C., Wu F., Zhu X., Xu J. Incorporation of β-sitosterol into the membrane increases resistance to oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation via estrogen receptor-mediated PI3K/GSK3β signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—General Subjects. 2013;1830(3):2538–2544. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loizou S., Lekakis I., Chrousos G. P., Moutsatsou P. β-Sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research. 2010;54(4):551–558. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leroy E. M., Baize S., Volchkov V. E., et al. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. The Lancet. 2000;355(9222):2210–2215. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reed D. S., Hensley L. E., Geisbert J. B., Jahrling P. B., Geisbert T. W. Depletion of peripheral blood T lymphocytes and NK cells during the course of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques. Viral Immunology. 2004;17(3):390–400. doi: 10.1089/vim.2004.17.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang Y. S., Park Y. G., Kim B. K., et al. Angiotensin II stimulates the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor through the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in cultured mouse podocytes. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2006;36(2):377–388. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srikiatkhachorn A., Ajariyakhajorn C., Endy T. P., et al. Virus-induced decline in soluble vascular endothelial growth receptor 2 is associated with plasma leakage in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(4):1592–1600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01642-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moraes L. A., Piqueras L., Bishop-Bailey D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;110(3):371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wojciechowska-Durczynska K., Krawczyk-Rusiecka K., Cyniak-Magierska A., Zygmunt A., Sporny S., Lewinski A. The role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase subunits in chronic thyroiditis. Thyroid Research. 2012;5(1, article 22):4. doi: 10.1186/1756-6614-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher-Hoch S., McCormick J. B., Sasso D., Craven R. B. Hematologic dysfunction in Lassa fever. Journal of Medical Virology. 1988;26(2):127–135. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim M.-S., Kim S.-H. Inhibitory effect of astragalin on expression of lipopolysaccharideinduced inflammatory mediators through NF-κB in macrophages. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2011;34(12):2101–2107. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daniel A. N., Sartoretto S. M., Schmidt G., Caparroz-Assef S. M., Bersani-Amado C. A., Cuman R. K. N. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities of eugenol essential oil in experimental animal models. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2009;19(1):212–217. doi: 10.1590/s0102-695x2009000200006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chou T.-C. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of paeonol in carrageenan-evoked thermal hyperalgesia. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;139(6):1146–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood J. P., Silveira J. R., Maille N. M., Haynes L. M., Tracy P. B. Prothrombin activation on the activated platelet surface optimizes expression of procoagulant activity. Blood. 2011;117(5):1710–1718. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-311035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tak P. P., Firestein G. S. NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(1):7–11. doi: 10.1172/jci11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang W.-L., Chen X.-G., Zhu H.-B., Gao Y.-B., Tian J.-W., Fu F.-H. Paeoniflorininhibits systemic inflammation and improves survival in experimental sepsis. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2009;105(1):64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cybulsky M. I., Fries J. W. U., Williams A. J., et al. Gene structure, chromosomal location, and basis for alternative mRNA splicing of the human VCAM1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(17):7859–7863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marfe G., Tafani M., Indelicato M., et al. Kaempferol induces apoptosis in two different cell lines via Akt inactivation, bax and SIRT3 activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2009;106(4):643–650. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuo W.-T., Tsai Y.-C., Wu H.-C., et al. Radiosensitization of non-small cell lung cancer by kaempferol. Oncology Reports. 2015;34(5):2351–2356. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee H. S., Cho H. J., Kwon G. T., Park J. H. Kaempferol downregulates insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and ErbB3 signaling in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014;19(3):161–169. doi: 10.15430/jcp.2014.19.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saeed M. F., Kolokoltsov A. A., Freiberg A. N., Holbrook M. R., Davey R. A. Phosphoinositide-3 kinase-akt pathway controls cellular entry of ebola virus. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000141.e1000141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooke J. P. NO and angiogenesis. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003;4(4):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5688(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fulton D., Gratton J.-P., McCabe T. J., et al. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399(6736):597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Babaei S., Teichert-Kuliszewska K., Zhang Q., Jones N., Dumont D. J., Stewart D. J. Angiogenic actions of angiopoietin-1 require endothelium-derived nitric oxide. The American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162(6):1927–1936. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64326-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jing S., Xiaojiang Z. Professor Zhang Shiqing's experience on treating pediatric allergic purpura with Xijiao Dihuang decoction. Journal of Gansu College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2005;3, article 003 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: the 136 compounds information of XJDH.

Table S2: the relevant biological processes of the candidate targets.