Abstract

BACKGROUND

Poor adherence to medication regimens is common, potentially contributing to the occurrence of related disease.

OBJECTIVES

The authors sought to assess the risk of fatal stroke associated with nonadherence to statin and/or antihypertensive therapy.

METHODS

We conducted a population-based study using electronic medical and prescription records from Finnish national registers in 1995 to 2007. Of the 58,266 hypercholesterolemia patients aged 30+ without pre-existing stroke or cardiovascular disease, 532 patients died of stroke (cases), and 57,734 remained free of incident stroke (controls) during the mean follow-up of 5.5 years. We captured year-by-year adherence to statin and antihypertensive therapy in both study groups and estimated the excess risk of stroke death associated with nonadherence.

RESULTS

In all hypercholesterolemia patients, the adjusted odds ratio for stroke death (odds ratio; 95% confidence interval) for nonadherent compared with adherent statin users was 1.35 (1.04 to 1.74) 4 years before and 2.04 (1.72 to 2.43) at the year of stroke death or the end of the follow-up. In hypercholesterolemia patients with hypertension, relative to those who adhered to statins and antihypertensive therapy, the odds ratio at the year of stroke death was 7.43 (5.22 to 10.59) for those nonadherent both to statin and antihypertensive therapy, 1.82 (1.43 to 2.33) for those non-adherent to statin but adherent to antihypertensive therapy, and 1.30 (0.53 to 3.20) for those adherent to statin, but nonadherent to antihypertensive, therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals with hypercholesterolemia and hypertension who fail to take their prescribed statin and antihypertensive medication experience a substantially increased risk of fatal stroke. The risk is lower if the patient is adherent to either one of these therapies.

Keywords: adherence, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, mortality, statin and antihypertensive therapy, stroke

Responsible for 12% of all deaths worldwide, stroke is the second leading cause of mortality after ischemic heart disease (1). Despite a decline of 20% in age-standardized stroke mortality rates from 1990 to 2013, the number of stroke deaths has increased by 40% (2). Moreover, stroke accounted for a total of 66.4 million disease-adjusted life years in people aged 60 years or older in 2010, and this burden of disease is predicted to increase by 44% from 2004 to 2030 (3,4).

High blood pressure and high cholesterol concentration are key risk factors for stroke for which effective pharmacological therapies are available. Evidence from trials suggest that statin treatment reduces stroke risk by between 15% and 25%, irrespective of the patient’s baseline cardiovascular disease risk (5,6). For stroke prevention, the benefits of antihypertensive medication are of similar magnitude to those seen for statins, such that a 15% to 25% decrease in 5-year stroke risk is apparent, irrespective of baseline stroke risk (7). Stroke rates also appear to decline in proportion to the reduction in cholesterol and blood pressure (6,8).

In clinical settings, a major obstacle for the full benefits of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive treatments is the nonadherence of patients to drug therapy (9–11); that is, a failure to take their medications as prescribed by their physician. At least 3 studies have shown a significantly increased risk of stroke in hypertensive patients who do not adhere to their antihypertensive treatment regimens relative to those who are more compliant (9–11). Few studies have examined the effects of nonadherence to statin use on stroke risk, however, and we are aware of no studies that have quantified the extent to which nonadherence to statin therapy is associated with stroke risk among hypercholesterolemia patients with hypertension.

In the present study, we used records from nationwide drug prescription, hospitalization, and death registers to determine the risk of fatal stroke associated with nonadherence to statin therapy among hypercholesterolemia patients. In addition, we examined the risk of fatal stroke associated with nonadherence to statin therapy, antihypertension therapy, or both among hypercholesterolemia patients with a hypertension diagnosis.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

We conducted a record-linkage study using the Statistics Finland Labor Market data, which cover all permanent residents in Finland, and cause-specific death records from the National Death Register during the period January 1, 1995, to December 31, 2007. Labor Market data are collected on an annual basis from different administrative sources to provide labor force statistics. We used the individually unique personal identification codes of Finnish residents to link these data to medication records from the National Drug Reimbursement Register and the Drug Prescription Register curated by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, along with information on principal causes of hospitalizations between January 1, 1987, and December 31, 2007, provided by the National Institute for Health and Welfare. Ethical permissions for this project were provided by the ethics committee of Statistics Finland (linkage permission TK 53-1519-09).

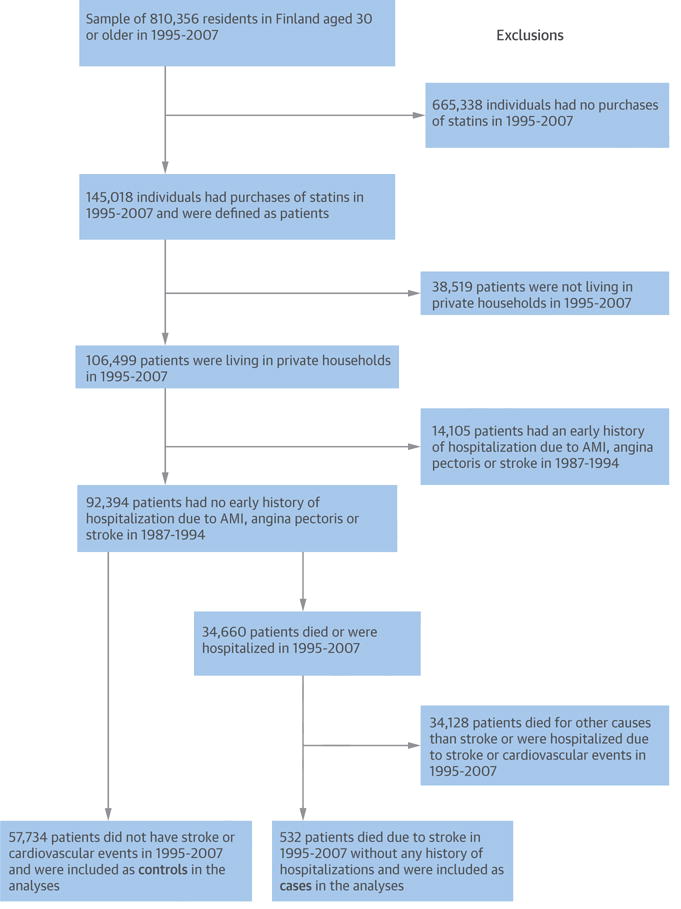

In accordance with the data protection regulations of living individuals in Finland, Statistics Finland provided a representative 11% sample of the national population and an oversample of individuals who died in the period between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2007. Our data covered a total 80% of all deaths in Finland during that period. We used sampling weights, constructed from the sampling probabilities, to take account of the sampling design. Thus, the results derived from the analyses of this study are nationally representative. We restricted the sample to persons >30 years of age because stroke events are rare in younger people (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Flow Diagram for the Derivation of the Analytical Sample.

AMI = acute myocardial infarction.

ADHERENCE TO STATIN THERAPY

Information on purchase of statins drugs was drawn from the Drug Prescription Register. Since 1994, all prescription reimbursed by the sickness insurance scheme have been recorded in this register. Hypercholesterolemic individuals requiring continuous statin therapy were identified from this register from January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2007, coded as C10AA according to the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (12). The Social Insurance Institution obtains these data from all pharmacies in Finland as part of the national drug reimbursement scheme. These records cover the entire study population but exclude institutionalized patients.

In our study, year-by-year adherence to statin therapy was measured for the days covered by filled prescriptions (i.e., purchases) of statins. The rates of filled prescriptions are considered an accurate measure of medical adherence in a closed pharmacy system, such as in Finland, especially when the refills are measured at several points of time (13). In Finland, all prescriptions are written by a physician, and each purchase can cover a maximum use of 3 months.

For the analysis, annual adherence and nonadherence were defined on the grounds of days covered by the purchases of statins. A period of 365 days was defined as adherent for a patient if he or she had 3 or more purchases (each covering the use for 3 months) of statin drugs within that year, and the time between the first and the last purchase was 180 days or more. This period of 365 days was defined as nonadherent if these requirements were not met. This corresponds to an adherence level of <80%, a generally used definition of poor medication adherence (14). To examine dose–response association, we used the adherence thresholds of <30% (poor adherence), 30% to 80% (intermediate adherence), and >80% (high adherence) defined by yearly statin purchases of none to 1, 2, and 3 or more, respectively. Individuals who had only 1 purchase over the whole follow-up period from 1995 to 2007 were removed from the analyses because it may be an indication that statins produced significant side effects.

ADHERENCE TO ANTIHYPERTENSIVE THERAPY

For the analyses of hypercholesterolemia individuals with hypertension, we also obtained data for antihypertensive drugs, coded as CO2 (antihypertensive agents), CO3 (diuretic agents), CO7 (beta-blocking agents), CO8 (calcium channel blockers), or CO9 (agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system). Measuring and defining adherence to antihypertensive therapy were the same as those of statin therapy described in the preceding text.

CASES AND CONTROLS

Hypercholesterolemia patients were divided into 2 groups: those who died from a stroke (cases) and those who did not have stroke or cardiovascular events between 1987 and 2007 (controls). The hospitalizations or deaths due to stroke during the follow-up were indicated by an underlying cause of hospitalization or death of a cerebrovascular disease (International Classification of Diseases 10 [ICD-10] codes I60–I69). To minimize the possibility of reverse causality, patients who had a history of nonfatal stroke or cardiovascular event (ICD-10 codes I00–I99 except I10) before fatal stroke were excluded from the analyses. The control group consisted of hypercholesterolemia patients who had no record of cardiovascular or stroke events before, or during, the follow-up period in mortality and hospitalization registers.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Sociodemographic factors extracted from the Statistics Finland Labor Market data file included sex, age, and educational attainment. The 4 educational categories were based on the highest educational qualification: basic education, secondary education, lower tertiary education, and higher tertiary education.

History of chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 codes E10–E14) and cancer (ICD-10 codes C0–C97) between January 1, 1987, and December 31, 1994 (i.e., before the assessment period for adherence) were included as covariates in the analyses. The use of drugs for the treatment of thrombus and diabetes mellitus was identified from the Drug Reimbursement Register during the follow-up from January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2007.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used binary and multinomial logistic regression to examine the year-by-year association between adherence to statin therapy and fatal stroke. In addition, we performed corresponding analyses between adherence to statin and antihypertensive therapies and fatal stroke among statin users diagnosed with hypertension. Odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted for age, sex, education, diabetes mellitus, and history of cancer. Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software, version MP 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

The characteristics of the 58,266 hypercholesterolemia patients at the time of stroke, death, or at the end of the follow-up by case are reported in Table 1. Cases (i.e., those who died from stroke) were older and less educated than controls. Moreover, the cases were more often diagnosed with diabetes or cancer. Of the stroke deaths as the first presentation of the disease, 36% (n = 190) were ischemic, 32% (n = 168) hemorrhagic, 16% (n = 86) subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 16% (n = 88) other types.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Hypercholesterolemia Patients at the Time of Stroke Death or the End of Follow-Up

| Noncases n = 57,734 |

Fatal n = 532 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 64.3 (11.2) | 72.8 (9.7) |

|

| ||

| Male | 26,674 (46) | 242 (45) |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| Upper tertiary | 3,272 (6) | 10 (2) |

| Lower tertiary | 9,764 (17) | 43 (8) |

| Secondary | 17,828 (31) | 85 (16) |

| Basic | 26,770 (47) | 394 (74) |

|

| ||

| Diabetes | 1,117 (2) | 34 (6) |

|

| ||

| History of cancer | 950 (2) | 19 (4) |

|

| ||

| Follow-up, yrs | 5.5 (3.4) | 4.7 (3.0) |

|

| ||

| Medication* | ||

| Thrombus | 6,379 (11) | 173 (33) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10,843 (19) | 147 (28) |

| Hypertension | 39,403 (68) | 453 (85) |

Values are mean (SD) or n (%). Comparisons between noncases and cases were done with 2-sample t tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate. All p values are 0.001 or <0.001, except p = 0.743 in comparison of sex between noncases and stroke deaths.

Use of drugs against selected diseases during the follow-up.

ANALYSIS OF STROKE RISK ASSOCIATED WITH NONADHERENCE TO STATIN THERAPY

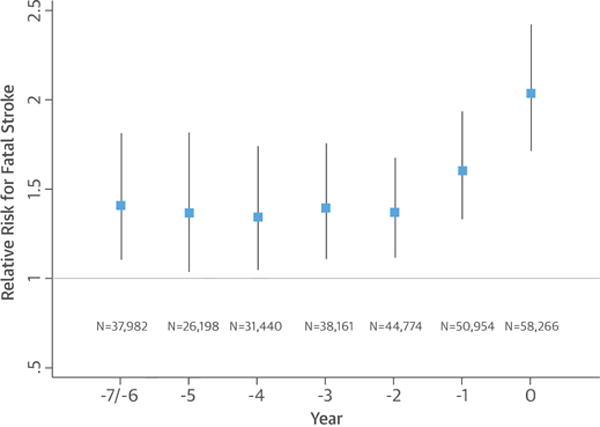

The proportion of adherence to statins was 58% in men and 60% in women. The corresponding proportion was 52% for those aged <57 years, 60% for those aged 57 to 65 years, 63% for those aged 66 to 72 years, and 61% for those aged >72 years (data not shown). Figure 2 shows results from the association between adherence to statin therapy and fatal stroke assessed retrospectively from the stroke death. An elevated risk of stroke death among individuals nonadherent to statin therapy was apparent, and this increased in magnitude in the year before the stroke death. Thus, for nonadherent compared with adherent patients, the multiply-adjusted ORs (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for stroke death were 2.04 (1.72 to 2.43), 1.61 (1.33 to 1.94), 1.37 (1.12 to 1.68), 1.35 (1.04 to 1.74), and 1.41 (1.10 to 1.81), at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 or 7 years before death from stroke or the end of the follow-up, respectively. The duration of the prescribed treatment differed (p value <0.001) between cases (5.5 years) and controls (4.2 years), a mean of 5.1 (SD 3.1) years at the end of follow-up, but the proportion of adherence to statins was 54% in both groups during the first 2 years of treatment. An additional adjustment for treatment duration had little effect on the estimates: ORs for stroke death for nonadherent relative to adherent patients were 1.90 (1.57 to 2.29), 1.46 (1.20 to 1.76), 1.22 (0.99 to 1.51), and 1.24 (0.98 to 1.57), at 0, 1, 2, and 3 years before death from stroke or the end of the follow-up, respectively. In analyses stratified by treatment duration (below vs. above median use, cutoff 5.1 years), the corresponding ORs were 1.70 (1.37 to 2.10), 1.48 (1.15 to 1.89), 1.22 (0.92 to 1.64), and 1.24 (0.85 to 1.75) among individuals below the median use, and 2.45 (1.84 to 3.27), 1.60 (1.20 to 2.14), 1.37 (1.02 to 1.84), and 1.39 (1.04 to 1.87) among those above the median use.

FIGURE 2. Annual ORs (95% CIs) for Fatal Stroke According to Nonadherence vs. Adherence to Statin Therapy Before Stroke Death or the End of Follow-Up.

Odds ratios (ORs) are adjusted for age, sex, diabetes mellitus, and history of cancer.

CI = confidence interval.

ANALYSIS OF DOSE–RESPONSE ASSOCIATION

Complementary models (Online Table 1) show year-by-year analysis of stroke risk using the three-level adherence definition of high, intermediate and poor adherence to statin therapy. In each year before the fatal stroke event, the largest risk of stroke death was observed among the patients with poor adherence. In the year of the event, for example, the odds of stroke death in this group was 2.23 (95% CI: 1.81 to 2.74) times higher compared with that for individuals with high adherence. The corresponding OR for the patients with intermediate adherence was 1.84 (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.51).

ANALYSIS OF STROKE RISK ASSOCIATED WITH NONADHERENCE TO STATIN AND ANTIHYPERTENSIVE THERAPY

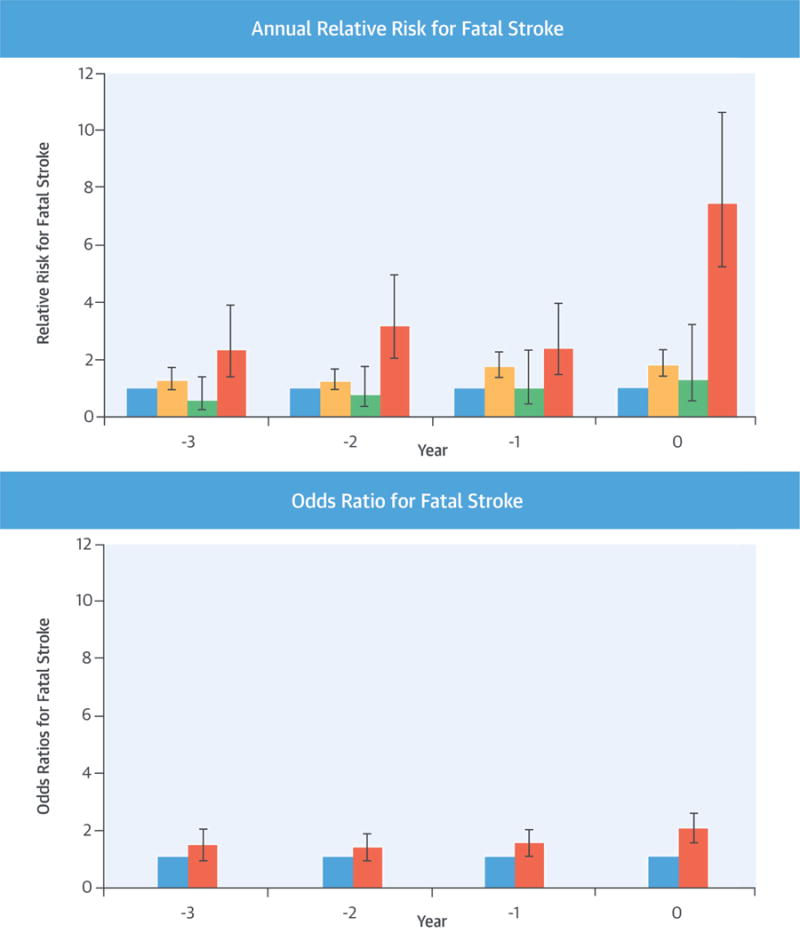

The Central Illustration illustrates annual relative risk ratios for fatal stroke according to different categories of adherence before the first presentation of stroke or the end of follow-up among statin users diagnosed with hypertension. The reference group in every comparison is patients who are adherent both to statin and antihypertensive therapy. Among patients nonadherent to statin therapy, but adherent to antihypertensive medication, the covariate-adjusted ORs for stroke death were 1.82 (95% CI: 1.43 to 2.33), 1.76 (95% CI: 1.36 to 2.27), 1.24 (95% CI: 0.93 to 1.65), and 1.27 (95% CI: 0.93 to 1.74), respectively, at 0, 1, 2, and 3 years before death from stroke or the end of the follow-up.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Poor Adherence to Statin and Antihypertensive Therapy: Risk of Fatal Stroke.

(Upper panel): Annual relative risk ratios for fatal stroke according to different categories of adherence to drug treatment before stroke death among statin users diagnosed with hypertension. On the horizontal axis is years to stroke death or the end of follow-up in (i = blue) patients adherent to statin and antihypertensive therapy (reference category n = 22,070); (ii = yellow) patients nonadherent to statin therapy and adherent to antihypertensive therapy (n = 13,494); (iii = green) patients adherent to statin therapy and nonadherent to antihypertensive therapy (n = 754); and (iv = red) patients nonadherent to statin and antihypertensive therapy (n = 1,884). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. (Lower panel): Annual odds ratios for fatal stroke according to nonadherence (n = 15,716, red) versus adherence (reference category n = 21,688, blue) to statin therapy before stroke death or the end of follow-up among statin users not diagnosed with hypertension. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The corresponding ORs for stroke death were 1.30 (95% CI: 0.53 to 3.20), 1.02 (95% CI: 0.44 to 2.33), 0.77 (95% CI: 0.33 to 1.76), and 0.56 (95% CI: 1.23 to 1.38), respectively, at 0, 1, 2, and 3 years before death from stroke or the end of the follow-up among patients adherent to statin therapy, but nonadherent to antihypertensive therapy. Finally, the corresponding adjusted ORs for stroke death among patients nonadherent both to statin and antihypertensive therapy compared with adherent patients were 7.43 (95% CI: 5.22 to 10.59), 2.39 (95% CI: 1.44 to 3.95), 3.17 (95% CI: 2.04 to 4.93), and 2.34 (95% CI: 1.41 to 3.88).

ANALYSIS OF STROKE RISK AMONG STATIN USERS WITHOUT HYPERTENSION

Year-by-year analysis of the association between adherence to statin therapy and fatal stroke among statin users who were not diagnosed with hypertension is shown in Online Figure 1. The adjusted ORs for stroke death were 2.00 (95% CI: 1.52 to 2.60), 1.50 (95% CI: 1.11 to 2.02), 1.35 (95% CI: 0.96 to 1.89), and 1.43 (95% CI: 0.98 to 2.09) at 0, 1, 2, and 3 years before death from stroke or the end of the follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Our population-based, nationwide analysis shows patients nonadherent to statin and antihypertensive therapies had >7-fold increased odds of fatal stroke at the year of stroke death whereas patients nonadherent to statins, but adherent to antihypertensive therapy, had a 1.8-fold increased risk, and those adherent to statins, but nonadherent to antihypertensive treatment, a 1.3-fold increased risk compared with patients adherent to both treatments. In analysis of hypercholesterolemia with and without hypertension, those who subsequently died from stroke already had a lower adherence to statin therapy 7 years before death compared with patients who did not experience stroke during the follow-up. As opposed to adherent patients, nonadherence to statin therapy was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of fatal stroke in the last year of life. Our dose–response analyses based on categories of high, intermediate, and low adherence to statin therapy confirmed that the near- and long-term risk of fatal stroke was associated with a stepwise decline in adherence.

COMPARISON WITH OTHER STUDIES

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the association of fatal stroke with nonadherence to statin and antihypertensive therapy among statin users diagnosed with hypertension. Our findings are concord with previous analyses addressing separately adherence to statin and antihypertensive treatments that indicated lower adherence to these therapies to be associated with a higher risk of stroke or other cardiovascular events (10,11,15). We have previously found that patients nonadherent to antihypertensive medication had 5.7 (95% CI: 5.1 to 6.4) times higher odds of stroke death when compared with adherent patients in the last year of life (11). Results from an Italian study reported that, when compared with patients with poor adherence, patients with good or excellent adherence to antihypertensive medication had a 30% to 50% lower risk for a composite outcome of all-cause mortality, fatal or nonfatal stroke, and fatal or nonfatal acute myocardial infarction, although separate analyses for the stroke outcomes indicated no statistically significant differences between the adherence groups (10). With regard to statin treatment, analyses of administrative data over 3-year follow-up in Italy suggested a 40% risk reduction in the composite outcome of all-cause death, nonfatal stroke, and nonfatal acute myocardial infarction in patients with intermediate to high adherence, compared with low adherence to statin therapy. Separate analyses for fatal stroke were not performed in that study (15).

Our study has several strengths, such as the large-scale, high-quality, population-based sample of permanent residents in Finland with an 80% oversample of deaths and linkage to comprehensive drug and hospitalization registration that allowed us to conduct a year-by-year analysis of adherence in relation to fatal stroke events. The nationwide closed record system for both prescriptions and deaths meant that there was virtually no dropout or sample attrition during the follow-up. Information on hospitalization was essential to ensure that the patients were free of stroke and cardiovascular disease at baseline and thus were targets for primary, rather than secondary, prevention. We assessed stroke risk on the basis of records of fatal stroke, which is a valid stroke outcome. For example, in a study of in-hospital deaths coded for participants in the Minnesota Heart Study (16), death certificates missed a proportion of stroke deaths, but deaths that were identified as stroke deaths were virtually all correct on the death certificates. The Finnish death register, which we used, has been ranked high with respect to reliability and accuracy in international comparisons (17). Therefore, our findings are likely to be free of bias due to coding error.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

First, although pharmacy refill records are objective measures and are collected routinely, they do not measure whether the participants actually took the medications. We might have underestimated nonadherence if dispensed medications were not used. However, high concordance between prescription claims and pill counts has been demonstrated, suggesting that the rate with which patients refill their medications with new purchases usually is consistent with the rate they consume them (18). Second, adherence to the statin or antihypertensive therapy does not necessarily mean that elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol or blood pressure, or other risk factors affecting stroke risk, have been taken under full control. It is possible that adherent patients that have met treatment targets have a lower stroke risk than those adherent patients who did not meet these targets. Conversely, nonadherent patients with poorly controlled LDL cholesterol or blood pressure are likely to have a higher stroke risk than nonadherent counterparts with the more favorable cholesterol levels. Thus, we expect that the relative risk of stroke among those with high adherence and LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, and other risk factors under control compared with those with low adherence and uncontrolled LDL cholesterol or blood pressure may be greater than we observed for adherent versus nonadherent patients without information on cholesterol or blood pressure control. Third, the healthy user bias (that is, the correlation between adherence and other behavior-related risk factors) may artificially inflate associations between nonadherence and disease outcomes in observational studies on preventive medications, such as ours (19). However, this is an unlikely explanation for the accelerated decline in adherence that we observed 4 years before stroke death. Fourth, information on some potential confounding factors, such as smoking and dementia, was not available. Fifth, the stringent exclusion criteria of our study population may have affected the assessment of prevalence of adherence to medication. Further research to determine the generalizability of our findings is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

We have shown that a lower adherence to statin and antihypertensive therapy is associated with a considerably increased risk of stroke death 4 years before the event among hypercholesterolemia patients diagnosed with hypertension. For all statin users, irrespective of hypertension, we found a lower adherence to statins 7 years before a fatal stroke. Our study has important clinical implications emphasizing the benefits of adherence to statin therapy for hypercholesterolemia patients and the substantial harms of nonadherence to statin and antihypertensive therapy for hypercholesterolemia patients with hypertension. Adherence appears to be a key factor in order to minimize serious complications, such as fatal stroke events. Given the difficulty to obtain randomized trial evidence on the effect of adherence to statin or antihypertensive therapy, observational data, such as ours, represent the most valid source of information on this topic.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

According to data from a population-based cohort linked to nation-wide electronic medical and prescription records, patients nonadherent to statin and antihypertensive therapies had significantly higher risk of fatal stroke than those who were adherent to both therapies, suggesting that nonadherence may be associated with substantial harms in cardiovascular disease–free patients with prescribed lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medication.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Future research should be directed toward developing strategies to improve medication adherence in patients with dyslipidemia and high blood pressure.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Martikainen is supported by the Academy of Finland, NordForsk and Horizon 2020. Dr. Kivimäki is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01AG034454); the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (K013351), an Economic and Social Research Council professorial fellowship, and NordForsk, the Nordic Programme on Health and Welfare.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- CI

confidence interval

- ICD 10

International Classification of Diseases 10

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- OR

odds ratio

APPENDIX

For a supplemental figure and table, please see the online version of this article.

Footnotes

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Estimates for 2000–2012. WHO Global Health Observatory; 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html. Accessed December 27, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet. 2015;385:549–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380:581–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amarenco P, Labreuche J. Lipid management in the prevention of stroke: review and updated meta-analysis of statins for stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:453–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Sundström J, Arima H, Woodward M, et al. Blood pressure-lowering treatment based on cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2014;384:591–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzaglia G, Ambrosioni E, Alacqua M, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medications and cardiovascular morbidity among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2009;120:1598–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.830299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposti LD, Saragoni S, Benemei S, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medications and health outcomes among newly treated hypertensive patients. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;3:47–54. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S15619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herttua K, Tabák AG, Martikainen P, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive therapy prior to the first presentation of stroke in hypertensive adults: population-based study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2933–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Collaboration Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Application for ATC Codes. 2011 Available at: http://www.whocc.no/atc/application_for_atc_codes/. Accessed December 27, 2015.

- 13.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebrahim S. Detection, adherence and control of hypertension for the prevention of stroke: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i–iv. 1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esposti LD, Saragoni S, Batacchi P, et al. Adherence to statin treatment and health outcomes in an Italian cohort of newly treated patients: results from an administrative database analysis. Clin Ther. 2012;34:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iso H, Jacobs DR, Jr, Goldman L. Accuracy of death certificate diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage and nonhemorrhagic stroke. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:993–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathers CD, Fat DM, Inoue M, et al. Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:171–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, et al. Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older persons. Med Care. 2006;44:471–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207817.32496.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Dormuth C, et al. Adherence to lipid-lowering therapy and the use of preventive health services: an investigation of the healthy user effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:348–54. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.