Abstract

Study Objectives:

To characterize the prospective associations of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with future echocardiographic measures of adverse cardiac remodeling

Methods:

This was a prospective long-term observational study. Participants had overnight polysomnography followed by transthoracic echocardiography a mean (standard deviation) of 18.0 (3.7) y later. OSA was characterized by the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour). Echocardiography was used to assess left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function and mass, left atrial volume and pressure, cardiac output, systemic vascular resistance, and right ventricular (RV) systolic function, size, and hemodynamics. Multivariate regression models estimated associations between log10(AHI+1) and future echocardiographic findings. A secondary analysis looked at oxygen desaturation indices and future echocardiographic findings.

Results:

At entry, the 601 participants were mean (standard deviation) 47 (8) y old (47% female). After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, baseline log10(AHI+1) was associated significantly with future reduced LV ejection fraction and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) ≤ 15 mm. After further adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, participants with higher baseline log10(AHI+1) had lower future LV ejection fraction (β = −1.35 [standard error = 0.6]/log10(AHI+1), P = 0.03) and higher odds of TAPSE ≤ 15 mm (odds ratio = 6.3/log10(AHI+1), 95% confidence interval = 1.3–30.5, P = 0.02). SaO2 desaturation indices were associated independently with LV mass, LV wall thickness, and RV area (all P < 0.03)

Conclusions:

OSA is associated independently with decreasing LV systolic function and with reduced RV function. Echocardiographic measures of adverse cardiac remodeling are strongly associated with OSA but are confounded by obesity. Hypoxia may be a stimulus for hypertrophy in individuals with OSA.

Citation:

Korcarz CE, Peppard PE, Young TB, Chapman CB, Hla KM, Barnet JH, Hagen E, Stein JH. Effects of obstructive sleep apnea and obesity on cardiac remodeling: the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. SLEEP 2016;39(6):1187–1195.

Keywords: echocardiography, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, sleep apnea

Significance.

Obstructive sleep apnea is highly prevalent and often under-diagnosed especially during its initial years. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort provided an opportunity to study the natural history of sleep apnea in the general population and its effects on the heart. In this observational study, we identified an association between long term exposure to sleep apnea and a reduction in the strength of cardiac contraction independent of cumulative exposure to traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors. Studies of early detection and integrated treatment of OSA and obesity on long-term morbidity and mortality are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.1,2 OSA is characterized by intermittent episodes of upper airway obstruction with hypoxia, increased ventilatory effort, and disrupted sleep that lead to increased sympathetic activation, release of reactive-oxygen species, and inflammation.3 OSA is associated with hypertension, insulin resistance, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and increased CVD morbidity and mortality.2,4,5 Nocturnal oxygen desaturation from OSA is associated with left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, a marker of increased CVD risk.6,7 In subjects with severe OSA, positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy for 3 mo can reduce LV filling pressures,8,9 LV mass, right heart chamber sizes, and right ventricular (RV) pressure.10,11 As recently reviewed, a major challenge is to “understand whether obstructive sleep apnea is a mere epiphenomenon or an additional burden that exacerbates the cardiometabolic risk of obesity and the metabolic syndrome.”12

The aim of this study was to evaluate associations between baseline OSA and future measures of cardiac structure and function using echocardiography in Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study participants. We measured associations between OSA, its associated CVD risk factors including obesity and diabetes mellitus, and validated echocardiographic markers of cardiac remodeling and CVD risk in a longitudinal, population-based study.

METHODS

Participants

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study is a longitudinal, population-based study of OSA.13 In 1988, 6,947 state employees aged 30 to 60 y old, from five south central Wisconsin State agencies, were mailed a survey regarding sleep habits, health, and demographics. Seventy-two percent responded to the survey. From these respondents, a sampling frame was constructed from which a stratified random sample of 2,884 persons (nonpregnant and without recent airway cancer, airway surgery, or decompensated cardiopulmonary disease) were selected and invited to participate in overnight in-laboratory polysomnography studies that were repeated every 4 y. This report includes a set of 601 consecutive participants from the parent Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study scheduled to return for their 4-y follow-up sleep visits over the period that funding supported the echocardiography evaluations, a mean (standard deviation) 18.0 (3.7) (range 7.5–24.7) y after their baseline polysomnogram. This was essentially a randomly selected sample of those subjects free of CVD at the time of baseline polysomnogram that continued to participate in the cohort. Transthoracic echocardiography exams were performed between September 2009 and April 2014.

We performed an additional set of analyses looking at the ability of the nocturnal oxygen desaturation parameters mean SaO2 saturation and percent of time with SaO2 < 90% as predictor variables. Desaturation parameters became available in 2000 with the change in polysomnography equipment to electronic data collection. The SaO2 data used in this additional analysis were collected between August 24, 2000, through May 30, 2008, a mean of 9.3 (1.6) y prior to the echo data collection.

Polysomnography

Polysomnograms (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) were performed at the University of Wisconsin Hospital. Sleep state was determined by electroencephalography, electrooculography, and electromyography. Arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation, oral and nasal airflow, nasal air pressure, and thoracic cage and abdominal respiratory motion were used to detect OSA events. Sleep state and respiratory event scoring were performed by trained sleep technicians. Each 30-sec epoch of the polysomnographic record was scored for sleep stage using criteria described by Rechtschaffen and Kales14 and for breathing events. Cessation of airflow lasting ≥ 10 sec defined an apnea event. A discernible reduction in the sum of thoracic plus abdomen respiratory inductance plethysmography amplitude that lasted at least 10 sec and that was associated with a ≥ 4% reduction in oxyhemoglobin saturation defined a hypopnea event. The average number of apnea plus hypopnea events/hour of sleep defined the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). Reproducibility of single-night polysomnography was investigated by conducting second studies in 40 subjects separated by 7 to 14 days. These results showed that there was no significant difference between study nights in the percentage of time spent in each sleep stage or in the AHI. The mean ± standard error AHI for the first and second studies were 3.0 ± 1.1 and 3.9 ± 1.1 events/hour, respectively.13 The laboratory manager reviews all studies and rescores a subset of 20% for accuracy. Intrascorer reliability (based on intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]) = 0.95 for the AHI and interscorer (laboratory manager versus technician) ICC = 0.83.

Transthoracic Echocardiography

Imaging followed the American Society of Echocardiography Guidelines for acquisition, measurement, and interpretation.15,16 Images were obtained using an Acuson Sequoia 512 (Siemens Medical Solutions Inc., Mountain View, CA) with a 4V1c transducer by registered cardiac sonographers. Measurements were performed offline in triplicate and blinded from polysomnography results using a Syngo Workplace (Siemens, Issaquah, WA) workstation by a single registered cardiac sonographer (CEK) and overread by a level III echocardiographer (JHS). LV mass was calculated using two-dimensional-derived American Society of Echocardiography corrected cubed formula, at enddiastole. LV mass also was indexed by height (g/m2.7) and categorized as elevated when > 49 g/m2.7 in men and > 45g/m2.7 for women.17 LV ejection fraction was calculated with the biplane method of disks using a semi-automated border detection algorithm.18,19 Left atrial volume was measured using the biplane area-length method.20 LV diastolic function assessments used mitral valve pulsed wave Doppler and Doppler tissue imaging at rest and during the Valsalva maneuver.21 The LV outflow tract diameter and pulse wave Doppler were used to calculate stroke volume and cardiac output. Mean brachial pressure was obtained during the echocardiogram using a standardized protocol with an automated oscillometric upper arm sphygmomanometer (DINAMAP, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and the average of two consecutive stable readings was used to compute systemic vascular resistance. Mean arterial pressure, right atrial pressure estimated based on respiratory changes in inferior vena cava diameter and mean flow (LV outflow tract cardiac output), were used to calculate systemic vascular resistance (80 × [mean arterial pressure − right atrial pressure] / cardiac output) expressed in dyne × sec/cm5.

RV fractional area change, pulmonary systolic pressure (derived from the peak tricuspid regurgitation Doppler velocity and estimated right atrial pressure), pulmonary vascular resistance (10 × tricuspid valve peak regurgitation velocity / time-velocity integral from the RV outflow tract),22 and right atrial area23 were measured and calculated. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was obtained using two-dimensional guided M-mode tracings from apical four-chamber views, maximizing the image resolution and alignment between the cardiac apex and the tricuspid annulus. TAPSE was evaluated continuously and categorically (≤ 15 or > 15 mm). We included only echocardiographic parameters of reliable quality in our models. Some data points were missing from subjects with poor acoustic windows or incomplete Doppler signals. The echocardiographic parameters described in this manuscript were obtained from 96.3 % to 99.4% of participants, with the exceptions of pulmonary vein Doppler velocities, tricuspid regurgitation peak Doppler velocities, and derived pulmonary vascular resistance (90% present; missing values were due to poor quality signals or lack of tricuspid regurgitation).

Intrareader reproducibility was assessed by Pearson correlation coefficients and coefficients of variation (CV). A random sample of 10 echocardiograms was remeasured 2.2 (range 1.7– 2.4) y apart. The coefficient of variation was computed using the root mean-squared approach.24 Reproducibility was excellent for LV mass (r = 0.98, P < 0.001, CV = 6.1%), LV ejection fraction (r = 0.83, P = 0.003, CV = 3.0%), cardiac output (r = 0.91, P < 0.001 CV = 7.9%), left atrial volume (r = 0.92, P < 0.001, CV = 10.3%), pulmonary artery systolic pressure (r = 0.92, P < 0.001, CV = 7.3%), RV end-diastolic area (r = 0.96, P < 0.001, CV = 4.8%), right atrial area (r = 0.92, P < 0.001, CV = 7.2%), pulmonary vascular resistance (r = 0.92, P < 0.001, CV = 5.4%), and TAPSE (r = 0.83, P < 0.005, CV = 6.0%). These results are within the desirable reproducibility for echocardiographic outcome variables used in clinical trials or observational studies.16,25–27

Covariates

Interviews and questionnaires were administered by trained personnel on nights of the in-laboratory polysomnography studies. They were updated during echocardiography protocols to obtain information on medical history (e.g., physician-diagnosed diabetes mellitus, hypertension, lung diseases, self-reported physician-diagnosed CVD defined as myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, atherosclerosis, or revascularization procedure, and use of PAP treatment), medication use, cigarette smoking history, health behavior, CVD risk factor, and outcome variables. Measures of body habitus were as previously described.28 Seventeen subjects with CVD at baseline were not included in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). AHI was parameterized as log10(AHI+1) when analyzed as a continuous variable on grounds of model fit and because of skewed distributions and some zero values, as described previously.29 Four participants who used PAP during the baseline polysomnography were excluded from analyses when evaluating AHI as a continuous variable. We also evaluated oxygen saturation SaO2 measures as mean nocturnal SaO2 and percent of time with SaO2 < 90% for their ability to predict later echocardiographic parameters (see Tables S1 and S5 in the supplemental material). Additional sub-analyses were performed excluding all subjects that used PAP therapy at any time within the study (see Tables S2–S4 in the supplemental material). For echocardiographic descriptive values, results were presented using three AHI categories; normal: 0–4.9 events/hour, mild OSA: 5–14.9 events/hour, and moderate-severe OSA: ≥ 15 events/hour or PAP use at the echocardiography visit. Descriptive echocardiographic outcomes data is also presented stratified by baseline BMI categories (see Table S6 in the supplemental material).

Multivariable linear regression models were used to estimate associations of baseline AHI severity with future cardiac remodeling and function parameters. All models included log10(AHI+1), sex, and baseline age as independent variables. Final full models additionally included BMI, systolic blood pressure, and lipid-lowering medication use; current smoking status at baseline; any history of lung disease at baseline; change in BMI and systolic blood pressure; blood pressure medication use (never, at baseline, or use started after baseline), diabetes mellitus or glycemic control medication use (never, at baseline, diagnosed after baseline), and ever use of PAP. The same analyses were performed for both nocturnal O2 desaturation markers (see Table S5 for Mean SaO2 saturation in the supplemental material).

The a priori selection of covariates in the models was based on established associations and empirical observation between potential predictor variables and echocardiographic outcomes. These factors included variables that can act as confounders (i.e., diabetes mellitus or obesity) or as mediators (i.e., hyper-tension) of OSA effects on echocardiographic outcome measures. Models are presented unadjusted then, progressively, partially, and fully adjusted. We also wanted to account for those variables that showed significant changes between visits (baseline polysomnography to echocardiography visit) including “change in AHI”. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for main-effects variables. Additional models explored possible baseline interactions between BMI with AHI predicting future cardiac remodeling in fully adjusted models. A more conservative threshold (P < 0.01), was used for testing interaction terms because the exploratory nature of the models (see Table S7 in the supplemental material).

RESULTS

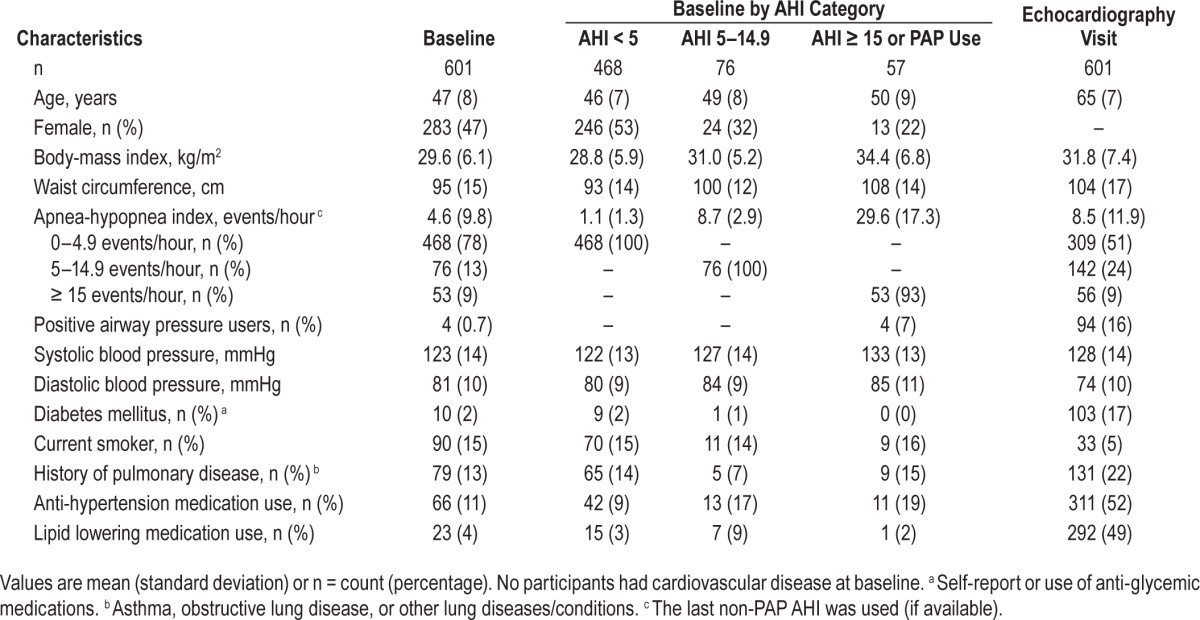

Demographic characteristics from the baseline polysomnography and the subsequent echocardiography visits are presented in Table 1. At the time of the baseline polysomnogram (baseline), the 601 participants were mean 47 (8) y old; 47% female, and 97% Caucasian. Mean (standard deviation) AHI was 4.6 (9.8) events/hour and only four subjects used PAP. A subset of 119 study participants had baseline polysomnograms apneas scored and were classified as having primarily obstructive or central apneas. Within that representative sample, 82% of apneas were obstructive. All study participants were reevaluated 18.0 (3.7) y later when they had a transthoracic echocardiogram. During this time, participants showed significant increases in BMI, from 29.6 (6.1) to 31.8 (7.4) kg/m2 (P < 0.001), and systolic blood pressure despite more participants taking blood pressure control medications (P < 0.01). Diabetes mellitus developed in many participants during follow-up (prevalence increased from 2% to 17%). A significant number of subjects became PAP users (0.7% at baseline to 16%, P < 0.001); among non-PAP users mean AHI increased from 4.6 (9.8) events/hour to 8.5 (11.9) events/hour (P < 0.001). At baseline, 17 participants (2.7%) had CVD and were excluded from the analysis; an additional 78 participants (13%) reported CVD at the echo-cardiography visit.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

For the secondary analysis focusing on the predictive ability of nocturnal O2 desaturation parameters, the sample was obtained nearly 10 y later. As expected, more subjects had received a diagnosis of CVD at baseline (n = 46) and 22 were using PAP at the first visit, resulting in a smaller sample size of 474 (Table S1 in the supplemental material).

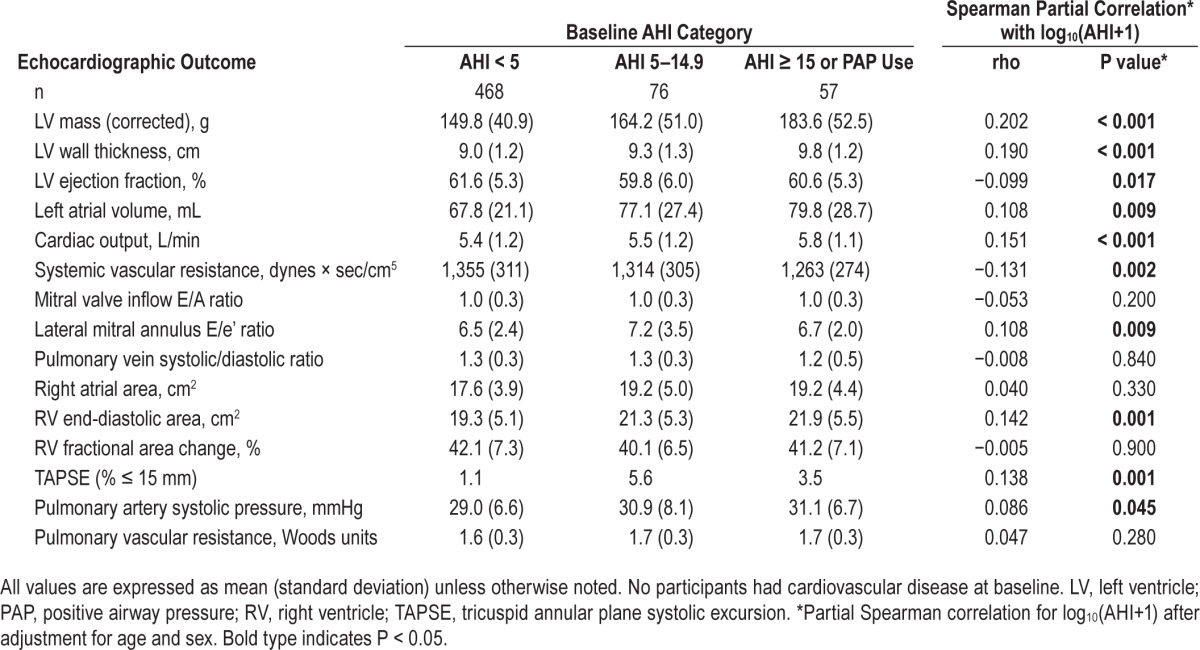

Table 2 shows associations between echocardiographic measurements presented by baseline AHI category, adjusted for age and sex. Baseline AHI was positively associated with future LV mass, LV wall thickness, left atrial volume, cardiac output, transmitral E/e' ratio, RV end-diastolic area, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, and TAPSE (% ≤ 15mm), and inversely associated with LV ejection fraction and systemic vascular resistance, after adjustment for age and sex. LV ejection fraction was significantly lower (r = −0.099, P = 0.017) among those with higher baseline AHI.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic outcomes stratified by baseline apnea-hypopnea index category.

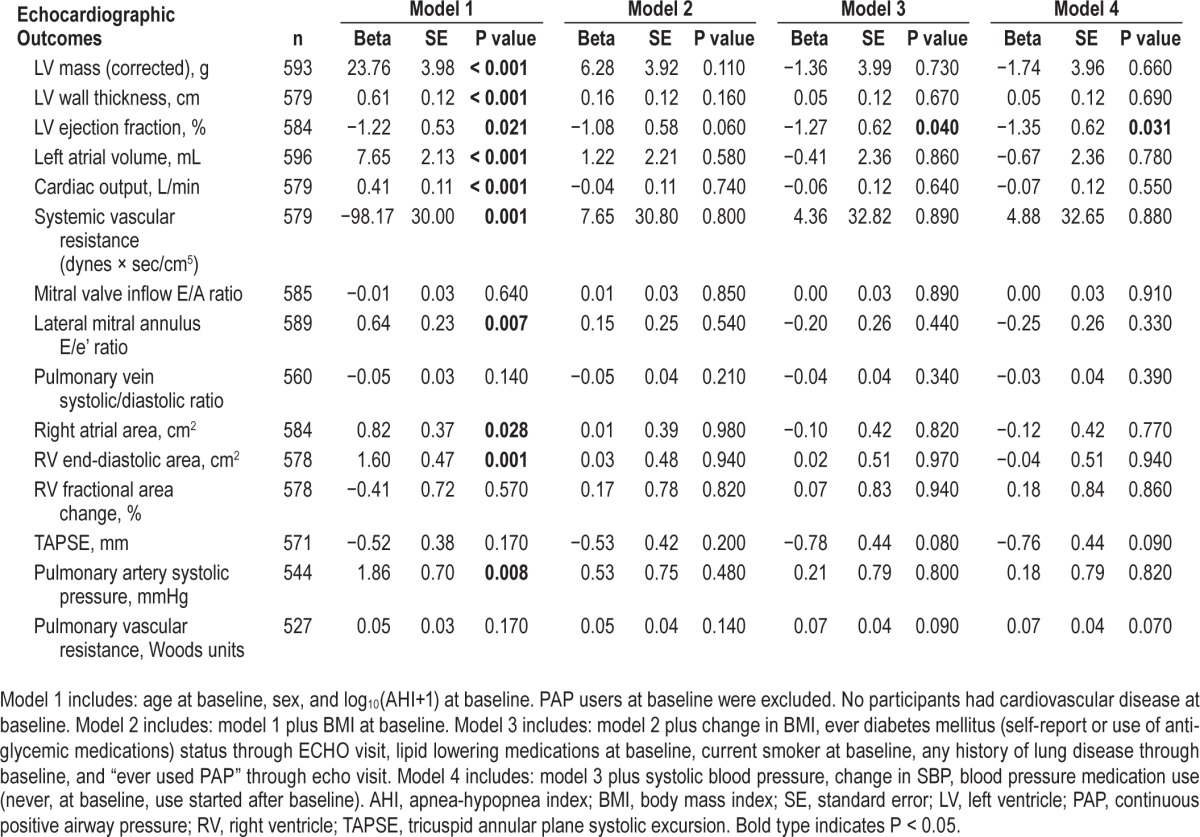

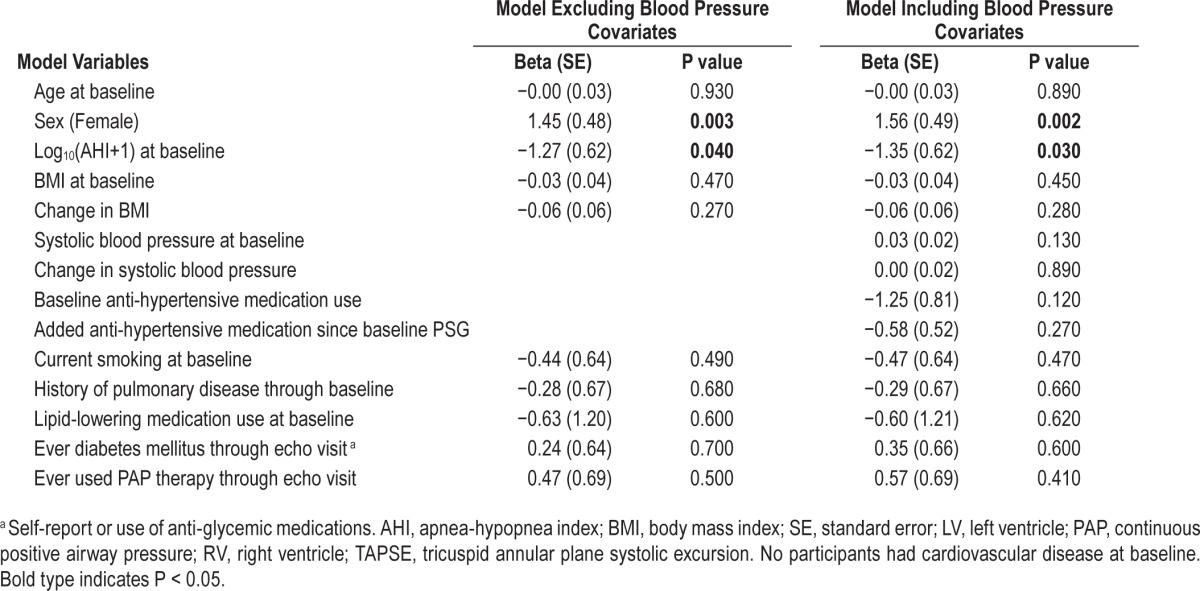

For echocardiographic variables that showed a significant association with baseline AHI severity, multivariate linear regression models were constructed and are presented in Table 3. Higher baseline log10(AHI+1) predicted future lower LV ejection fraction in the full model (Table 4). For every tenfold increase in AHI events/hour, there was an adjusted, independent decrease in ejection fraction of 1.3% (P = 0.039); for a participant with an AHI of 10 events/hour we expect a reduction in LV ejection fraction of 1.4% but for a participant with an AHI of 30 events/hour a reduction of 2.0%. Baseline OSA severity also was associated with several other future echocardiographic variables when age and sex were the only covariates; however, these relationships became nonsignificant when BMI was added to the model (Table 3). Cardiac output was positively associated with AHI, but this relationship became inverse and not significant after BMI was included in the models, suggesting a higher flow state driven by increased body size. This latter finding is consistent with the inverse association seen between AHI and systemic vascular resistance (P = 0.001), which probably was due to the higher cardiac output relative to the mean blood pressure elevation, which changed directionality and lost statistical significance after adjustment for BMI. In logistic regression models, baseline log10(AHI+1) independently predicted low TAPSE (≤ 15 mm) in the full model (odds ratio = 6.3 / log10(AHI+1), 95% confidence intervals = 1.3–30.5, P = 0.02). We also ran the same analyses excluding the 108 PAP users from the analysis (n = 493) with very similar results (see Tables S2–S4 in the supplemental material). We also tested the effect of “change in Log10(AHI+1)” between baseline and echocardiogram visit, adding it as a covariate to our full models excluding PAP users. Change in AHI was associated with increased wall thickness (Beta [Standard Error] = 0.26 [0.129] cm, P = 0.045) and increased E/e' ratio (0.574 [0.266], P = 0.032) whereas it did not modify the independent association between baseline AHI predicting LV ejection fraction and TAPSE.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression modeling results for baseline log10(AHI+1) predicting later echocardiographic outcomes.

Table 4.

Predictors of left ventricular ejection fraction (%).

Mean nocturnal SaO2 saturation and percent sleep time with SaO2 < 90% were independent predictors of LV mass and LV wall thickness in fully-adjusted models (see Table S5 in the supplemental material presenting Mean SaO2 saturation results). A 1% decrease in mean SaO2 saturation was associated with a LV mass increase of 4.38 g (P = 0.001), an increase in LV wall thickness of 0.14 cm (P < 0.001), and a RV area increase of 0.40 cm2 (P = 0.021). In these models, we did not identify an association with LV ejection fraction and TAPSE, likely explained by the removal of 46 subjects in whom CVD developed between the initial polysomnogram and this later polysomnographic evaluation. This interim analysis highlights the importance of hypoxia severity, not just the AHI, in promoting cardiac remodeling.30

To explore for possible effect modification of OSA associations with echocardiographic outcomes by obesity, we created models that included interaction terms between log10(AHI+1) and BMI (see Table S6 for echocardiographic outcomes by BMI categories and Table S7 for interaction models in the supplemental material) and presented the effects of Log10(AHI+1) centered at different BMI values.

DISCUSSION

The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study provided a unique opportunity to evaluate prospectively the long-term associations of OSA exposure on cardiac remodeling in the context of traditional CVD risk factors and temporal changes in body weight, systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and clinical OSA treatment.

OSA and Left Ventricular Systolic Function

We found that OSA independently was associated with lower LV ejection fraction on average more than a decade following initial OSA assessment. Similar results using LV M-mode measurements were found in a cross-sectional analysis of the Sleep Heart Health Study participants.31 Because the average LV ejection fraction of our participants in all AHI categories was in the normal range, our findings may indicate subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Although the independent negative effect of AHI on LV ejection fraction appears small from a clinical perspective, small differences in LV ejection fraction can have large implications at a population level and individuals vary in susceptibility to this effect. Recent work showed lower longitudinal systolic strain and strain rate and delayed diastolic strain rates as apnea severity increased in subjects with preserved ejection fraction.32,33 Another evaluation of OSA exposure and future effects on LV remodeling found that recent history of OSA symptoms was associated with diastolic dysfunction; prolonged exposure (> 10 y) to OSA was associated with systolic dysfunction and worse systemic hypertension.34 That study only had 220 subjects and retrospectively collected information about length of OSA symptoms from spouses or other household members. Our findings, in a larger sample with an objective history of length of OSA exposure and severity, validate and extend their initial observations. In another recent population study of more than 1,600 subjects, the only echocardiographic variable that was associated independently with history of OSA was left ventricular hypertrophy and only in women.35 Compared to clinical trials that enroll subjects with preexisting cardiovascular conditions,36,37 such as known coronary artery disease or with risk factors for heart failure, our cohort population did not show independent associations between OSA severity and diastolic dysfunction after adjustment for BMI.

OSA, Obesity, and LV changes

Obesity, a major risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea, is associated with chronic volume overload, increased stroke volume and cardiac output,38 as well as hypertension and hyperinsulinemia.39 These changes promote LV dilation and increased wall stress stimulating the development of LV hypertrophy with preserved ejection fraction.7 In a recent study of 720 individuals with preserved ventricular function and atrial fibrillation followed for 3.3 (1.5) y, OSA and BMI independently predicted increased LV mass on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.40 In our study, elevated cardiac output with lower systemic vascular resistance also was associated with higher BMI. In addition, obesity and OSA promote inflammation with leptin and insulin resistance, factors that contribute to LV hypertrophy and remodeling.7,41–43

In the Sleep Heart Health Study, OSA predicted LV mass after adjustment for traditional risk factors including BMI.31 Their cross-sectional study included a large sample of 2,058 participants. Recently a study of 1,645 participants from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study and the Sleep Heart Health study looked at the association between OSA and echocardiographic findings after an average interval of 13 y.35 Their main finding was a positive association between OSA categories and LV mass only in females (adjusted for height). They did not detect significant changes in systolic or diastolic function. Interestingly, our prospective study did not fully reproduce their findings regarding LV mass when using AHI as the marker for OSA severity, but we were able to detect a significant independent association between measures of O2 saturation and LV mass, LV wall thickness, and RV area in a smaller sample studied an average of 9.3 y before the echocardiograms.

OSA, Obesity, and RV changes

We confirmed previous reports of strong associations between RV measures of size with BMI, which may obscure a more subtle relationship with OSA.44 We demonstrated that lower mean SaO2 saturation independently predicted greater RV end diastolic area (P = 0.021) and that baseline AHI interacts with BMI as a predictor of increased RA area. Other studies have shown improvement in RV morphology after 6 mo of PAP therapy.45 Pulmonary hypertension was not prevalent in our cohort. A trend was observed for increasing pulmonary artery systolic pressure with baseline AHI or mean SaO2 saturation, but these findings were driven by obesity.

In summary, we were able to demonstrate associations between OSA severity and future, adverse echocardiographic measures of LV and RV function, size, and loading conditions, independent of traditional CVD risk factors in a large population-based study of the natural history of sleep-disordered breathing. The very long interval of observation in a cohort of this size is unique and appropriate to detect meaningful outcome data in this complex condition. Furthermore, we were able to detect significant independent associations between measures of O2 saturation and LV mass, LV wall thickness, and RV area in a smaller sample studied an average of 9.3 y before the echocardiograms. However, in these models, we did not identify associations with LV ejection fraction and TAPSE, likely because of the removal of 46 participants in whom CVD had developed between the initial polysomnogram and the later evaluation. These findings highlight the importance of hypoxia severity, not just the AHI, in promoting cardiac remodeling.30

Limitations

As an observational study, this study and the associations we identified may be affected by unmeasured variables. The study cohort is 97% Caucasian; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups. The severity of OSA in our cohort was representative of the general population at its inception, so few participants had severe OSA, limiting our ability to fully characterize echocardiographic associations with OSA across the full spectrum of OSA severity. A high percentage of participants were taking blood pressure medications at entry and many more started during the interval between baseline and echocardiogram visit. This may have obscured stronger associations between OSA and structural and functional cardiac adaptations. Because of the study design, only participants who survived the observational period and maintained reasonable mobility could attend the echocardiography visit, possibly underestimating the associations with abnormal echocardiographic findings.46

A large number of study participants affected by OSA started PAP treatment between baseline and echocardiography visits. Treatment of OSA and other CVD-protective therapies such as antihypertensive medications creates analytical challenges that are not solvable in an epidemiological study. That is, assuming these therapies are effective, rather than simply markers of healthy behavior, any positive associations found would be in spite of, not due to, the widespread use of therapeutic interventions.

A lack of objective compliance information precluded us from performing a detailed PAP analysis of PAP treatment effect, but our subanalysis excluding all PAP users did not alter our primary findings. Because echocardiography data were not available at the baseline visit, we cannot exclude the possibility of preexisting cardiac abnormalities at baseline, but all individuals with physician-confirmed CVD at baseline were excluded from these analyses.

Our a priori aim was to determine if OSA had an effect on hemodynamic conditions that resulted in cardiac remodeling, diastolic function, and ultimately systolic function. The number of echocardiographic variables studied is typical for an echocardiography analysis in order to assess groups of correlated measures that are physiologically or pathophysiologically related, such as cardiac remodeling (LV mass, LA size, RV end-diastolic area), ventricular systolic function (LV fractional shortening and ejection fraction, RV fractional area change and TAPSE), hemodynamics (cardiac output, pulmonary and systemic vascular resistance, LA pressure, and pulmonary pressures) and LV relaxation (E/A ratio, E/e', pulmonary vein S/D ratio, and LA pressure assessment). Therefore, we do not view our examination of multiple outcomes as an attempt only to find statistically significant associations or in need of multiple comparisons correction. We also do not view our findings as examinations for which a binary decision of “significant” or “not significant” is relevant. The precision with which our associations are measured and ultimate replication of our results is more important in interpreting our findings than simple P value testing. We note that many of our findings would not remain statistically significant if conservative Bonferroni corrections were applied to them. The readers and future scientists will need to interpret them in that light.

CONCLUSIONS

Prevalent OSA is an independent predictor of future decrements in LV and RV systolic function. Nocturnal hypoxia may be a stimulus for LV hypertrophy and RV remodeling in individuals with OSA. These structural cardiac abnormalities may mediate some of the increased CVD risk associated with OSA. A multidisciplinary approach for early diagnosis and treatment of OSA and the accompanying metabolic disturbances is required to prevent the development of cardiac abnormalities and to reduce CVD risk.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Korcarz was supported by grant K23 HL094760. Drs. Peppard, Young, Hla, Hagen, and Stein and Ms. Barnet were supported by R01 HL062252 and UL1 RR025011. Instrumentation provided by grants S10 RR021086 and S10 OD010569. The funding institutes played no role in the design and conduct of the study; no role in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the University of Wisconsin Atherosclerosis Imaging Research Program and the following for their valuable assistance: Laurel Finn, Amanda Rasmuson, Kathryn Pluff, Robin Stubbs, Nicole Salzieder, Kathy Stanback, Mary Sundstrom, and Dr. Steven Weber.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- CV

coefficient of variation

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- LV

left ventricle

- PAP

positive airway pressure

- RV

right ventricle

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- SE

standard error

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

REFERENCES

- 1.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen E, Hla KM. Increased Prevalence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AGN. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoeahypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O'Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gami A, Olson E, Shen W, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and the Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death A Longitudinal Study of 10,701 Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:610–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1561–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avelar E, Cloward T, Walker J, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy in severe obesity - Interactions among blood pressure, nocturnal hypoxemia, and body mass. Hypertension. 2007;49:34–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251711.92482.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayram N, Ciftci B, Durmaz T, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on left ventricular function assessed by tissue Doppler imaging in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:376–82. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butt M, Dwivedi G, Shantsila A, Khair OA, Lip GY. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in obstructive sleep apnea: impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:226–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colish J, Walker JR, Elmayergi N, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac remodeling as assessed by cardiac biomarkers, echocardiography, and cardiac MRI. Chest. 2012;141:674–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shivalkar B, Van de Heyning C, Kerremans M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: more insights on structural and functional cardiac alterations, and the effects of treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drager LF, Togeiro SM, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi G. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cardiometabolic risk in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography Endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's guidelines and standards committee and the chamber quantification writing group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roca GQ, Redline S, Claggett B, et al. Sex-specific association of sleep apnea severity with subclinical myocardial injury, ventricular hypertrophy, and heart failure risk in a Community-dwelling cohort: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities-Sleep Heart Health Study. Circulation. 2015;132:1329–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comaniciu D, Zhou X, Krishnan S. Robust real-time myocardial border tracking for echocardiography: an information fusion approach. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:849–60. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.827967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cannesson M, Tanabe M, Suffoletto MS, et al. A novel two-dimensional echocardiographic image analysis system using artificial intelligence-learned pattern recognition for rapid automated ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiologic expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1284–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:107–33. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbas A, Fortuin F, Schiller N, Appleton C, Moreno C, Lester S. A simple method for noninvasive estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol o. 2003;41:1021–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horton K, Meece R, Hill J. Assessment of the right ventricle by echocardiography: a primer for cardiac sonographers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:776–92. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland J, Altman D. Measurement error and correlation coefficients. Br Med J. 1996;313:41–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottdiener JS, Bednarz J, Devereux R, et al. American Society of Echocardiography recommendations for use of echocardiography in clinical trials. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:1086–119. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmieri V, Dahlof B, DeQuattro V, et al. Reliability of echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular structure and function: the PRESERVE study. Prospective Randomized Study Evaluating Regression of Ventricular Enlargement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1625–32. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamborini G, Pepi M, Galli CA, et al. Feasibility and accuracy of a routine echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular function. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:86–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peppard PE, Ward NR, Morrell MJ. The impact of obesity on oxygen desaturation during sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:788–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0773OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Zhang J, Gan TX, et al. Left ventricular dysfunction and associated cellular injury in rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:218–23. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00301.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chami HA, Devereux RB, Gottdiener JS, et al. Left ventricular morphology and systolic function in sleep-disordered breathing: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Circulation. 2008;117:2599–607. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altekin RE, Yanikoglu A, Baktir AO, et al. Assessment of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea patients with speckle tracking echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28:1917–30. doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altekin RE, Yanikoglu A, Karakas MS, Ozel D, Yildirim AB, Kabukcu M. Evaluation of subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea by automated function imaging method; an observational study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2012;12:320–30. doi: 10.5152/akd.2012.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang SQ, Han LL, Dong XL, et al. Mal-effects of obstructive sleep apnea on the heart. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:717–22. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Querejeta Roca G, Campbell P, Claggett B, Solomon SD, Shah AM. Right Atrial Function in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e003521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glantz H, Thunström E, Johansson MC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with worse diastolic function in coronary artery disease. Sleep Med. 2015;16:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wachter R, Lüthje L, Klemmstein D, et al. Impact of obstructive sleep apnoea on diastolic function. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:376–83. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collis T, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, et al. Relations of stroke volume and cardiac output to body composition: the strong heart study. Circulation. 2001;103:820–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Schillaci G, et al. Circulating insulin and insulin growth factor-1 are independent determinants of left ventricular mass and geometry in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1999;100:1802–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.17.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah RV, Abbasi SA, Heydari B, et al. Obesity and sleep apnea are independently associated with adverse left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcome in patients with atrial fibrillation and preserved ventricular function. Am Heart J. 2014;167:620–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lind L, Siegbahn A, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J. A detailed cardiovascular dharacterization of obesity without the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:E27–34. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capoulade R, Clavel MA, Dumesnil JG, et al. Insulin resistance and LVH progression in patients with calcific aortic stenosis: a substudy of the ASTRONOMER trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olea E, Agapito MT, Gallego-Martin T, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and diet-induced obesity: effects on oxidative status, sympathetic tone, plasma glucose and insulin levels, and arterial pressure. J Appl Physiol. 2014:706–19. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00454.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chahal H, McClelland R, Tandri H, et al. Obesity and Right Ventricular Structure and Function The MESA-Right Ventricle Study. Chest. 2012;141:388–95. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shivalkar B, Van de Heyning C, Kerremans M, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome - More insights on structural and functional cardiac alterations, and the effects of treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young T, Finn L, Peppard P, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep. 2008;31:1071–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.