Abstract

This work describes the production of high-specific activity 55Co and the evaluation of the stability of 55Co-metal-chelate-peptide complexes in vivo. 55Co was produced via the 58Ni(p,α)55Co reaction and purified using anion exchange chromatography with an average recovery of 92% and an average specific activity of 1.96GBq/µmol. 55Co-DO3A and 55Co-NO2A peptide complexes were radiolabelled at 3.7MBq/µg and injected into HCT-116 tumor xenografted mice. PET imaging and biodistribution studies were performed at 24 and 48 hours post injection and compared with that of 55CoCl2. Both 55Co-metal-chelate complexes demonstrated good in vivo stability by reducing the radiotracers’ uptake in the liver by 6-fold at 24 with ~1% ID/g and at 48 hours with ~0.5% ID/g, and reducing uptake in the heart by 4-fold at 24 hours with ~0.7% ID/g and 7-fold at 48 hours with ~0.35% ID/g. These results support the use of 55Co as a promising new radiotracer for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging of cancer and other diseases.

Keywords: 55Cobalt, PET imaging, Radiochemistry, NOTA, DOTA

Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a common imaging modality in nuclear medicine. Clinical interest in positron emitting metals has increased due to their longer half-lives, which are more suitable for radiolabeling macromolecules like antibodies, peptides, and nanoparticles over traditional PET isotopes such as 18F, 11C, and 15O (1, 2). Currently the most common radiometals used in PET imaging are 64Cu, 68Ga, 89Zr, and 86Y with 64Cu, 68Ga, and 89Zr being used in clinical trials (3–5). The chemistry of each metal is different and chelates need to be optimized for the radiometal of interest that will provide stable metal-chelate complexes in vivo.

55Co is another isotope of interest for PET imaging. It has a half-life of 17.5 hr, a positron branching ratio of 77%, and an average positron energy of 570 keV; qualities that make it well suited for imaging with peptides, small molecules, and antibodies (6–11). 55CoCl2 has previously been used clinically to image ischemia in stroke patients (12–15) and in late-onset epileptic seizures (16) due to its ability to mimic calcium uptake. However, it is important to study the preclinical pharmacological properties of this isotope when it will be incorporated into targeting ligands as imaging agents to probe other diseases. Thus, we investigated the biodistribution of free 55CoCl2 along with the stability of 55Co-chelate-peptide complexes in vivo.

55Co can be produced via several nuclear reactions such as 58Ni(p,α)55Co (17–20), 56Fe(p,2n)55Co (21, 22), and 54Fe(d,n)55Co (23, 24). The 54Fe(d,n)55Co has the highest measured cross section at low energies (8, 25), however 54Fe has a low natural abundance and thus this target may be cost-prohibitive for routine production in most laboratories. The 56Fe(p,2n)55Co reaction also creates undesirable 56Co (via 56Fe(p,n)56Co), a positron emitting isotope with a half-life of 77d which is chemically inseparable from 55Co. Additionally, the decay scheme for this isotope yields many high energy photons. The proton reaction on 58Ni has a higher cross section at lower energies than the proton reaction on 56Fe (19, 20, 22) making it more desirable for low-energy (15 MeV) cyclotrons. This method also produces a small amount of an inseparable side product, 57Co (t1/2=271.8d) at higher energies with a Q-value of 8.17 MeV. 57Co decays 100% by electron capture and has a low-energy gamma ray of 122 keV. In addition to 57Co, this method also produces another side product 57Ni (t1/2=35.6h), which can be used as a way to monitor the separation of 55Co from the starting nickel material by tracking the characteristic gamma rays via gamma spectroscopy.

The production of 55Co using natNi, and 58Ni have been previously reported (11, 18, 26, 27). The specific activity of 55Co has been investigated using both ion chromatography of productions using 58Ni (26) and via DOTA and NOTA titration of productions using natNi (27). High effective specific activity (ESA) of radiometals is important as metal contaminants have negative impacts on radiolabelling (28, 29). For best radiolabelling results using 55Co, ESA measurements must be performed and productions optimized so that high-specific activity material can be obtained.

In this work, we discuss the production of 55Co via the 58Ni(p,α)55Co reaction and report its ESA using both 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) titrations and Ion Chromatography (28). We also report the in vivo biodistribution 55CoCl2 and compare it with its 55Co-chelate complexes linked to a peptide up to 48 hrs. The macrocyclic chelates, DOTA and 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA), were chosen because they meet the coordination chemistry required to bind 55Co. DOTA and NOTA are commonly attached to peptides via one of their carboxylic acid arms, resulting in DO3A- and NO2A-peptide conjugates, respectively (30, 31). As a model system, we applied 55Co to a peptide ligand, L19K-FDNB, which has been shown to have a long blood clearance time (32). This property makes this peptide an optimal system for studying the stability of 55Co-chelate complexes as 55Co-DO3A-L19K-FDNB and 55Co-NO2A-L19K-FDNB in vivo at time points up to 48 hrs. The biodistribution data for 55CoCl2, 55Co-NO2A-L19K-FDNB, and 55Co-DO3A-L19K-FDNB were compared at 24 and 48 hrs post injection to establish the in vivo stability of 55Co chelated with NO2A- and DO3A-peptide conjugates in tumor-bearing mice.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Trace metals grade reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and used without purification and Milli-Q deionized water (18 MΩ cm−1) was used for all dilutions unless stated otherwise. All glassware and vials were acid washed in 8M HNO3 for 24 hrs prior to use. DOTA was purchased from Macrocyclics (USA). Two versions of the peptide L19K were synthesized by CPC Scientific consisting of the sequence DO3A- or NO2A-PEG4-GGNECDIARMWEWECFERK-CONH2, with a Cys-Cys disulfide bridge and polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a spacer between peptide and chelate. 58Ni was purchased from Isoflex (USA) with 99.48% isotopic enrichment.

Targetry and Irradiation

45–55 mg of 58Ni in powder form was plated onto a gold disk by electrodeposition as previously described by both McCarthy et al. (33) and Szelecsenyi et al. (34) The electroplating cell was 9 cm in height with an inner diameter of 1.8 cm. The bottom of the cell consisted of a teflon base that connected to the gold disk exposing a 5 mm circle. A graphite rod was used as the cathode and stirred the solution slowly as a voltage of 2.5 V was applied for ~12 hrs. The current remained between 8–20 mA throughout the process. Targets were irradiated on a 15 MeV cyclotron (CS-15) for 20–60 µAhrs and were able to withstand currents up to 30µA. Targets were allowed to sit for two hours prior to processing to allow short-lived contaminants to decay.

Purification

For processing, targets were placed in 10 mL of 9 M HCl and heated with reflux for approximately one hour in order to dissolve the nickel from the gold disk. Once the solution cooled it was placed in a 1 cm × 10 cm glass column (Biorad, USA) with 2.5 g AG1-X8 resin (Biorad, USA). In order to determine separation conditions, the eluate along with 10–40 mL of 9 M HCl were collected followed by another 10 mL of 0.5 M HCl to elute the 55Co. Fractions of 1 mL were collected and analyzed using an High Purity Germanium (HPGe) detector (Canberra, USA) and the final 55Co fractions were evaporated to dryness and reconstituted with 20 µL Milli-Q water. 55Co productions were analyzed using Ion Chromatography (28) for transition metal contamination.

Effective Specific Activity

DOTA titrations were performed in order to determine the effective specific activity of 55Co productions and the method was adapted from the TETA (1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-1,4,8,11-tetraacetic acid) titration method reported previously by McCarthy et al. (33) 1.2 MBq (5 µL) of 55Co was added to eight different amounts of DOTA in ammonium acetate pH 5.5 ranging from 4.3 × 10−4 µmol to 6.3 × 10−2 µmol. Final volume was brought to 50 µL using 0.5 M ammonium acetate buffer pH 5.5. The solutions were placed in an agitating incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. Solutions were cooled to room temperature and then centrifuged. A 1 µL aliquot from each DOTA concentration along with 1 µL of unbound 55Co, for use as a control, were spotted separately onto a silica plate for Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) using a 1:1 mixture of 10% w/v ammonium acetate and methanol as the eluent. Plates were analyzed using a Radio TLC Plate Reader (Bioscan, USA) and analyzed for the percent 55Co incorporated into DOTA. Data was plotted as the molar concentration of DOTA vs. % 55Co incorporation. The curve was fit using a sigmoid plot fit program in Prism (Graphpad, USA). The EC50 value, concentration of 55Co that bound to 50% of the DOTA molecules, was determined from this fit. The ESA was calculated as two times the EC50 value.

Animal Models

All animal care was performed as stated in the Guide for Care and Use for Laboratory Animals by the National Institutes of Health under a protocol approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University in St. Louis. Female athymic Nu/Nu mice (National Cancer Institute, USA) aged 6–9 weeks were anesthetized with a ketamine/xylazine cocktail (VEDCO, USA). 100 µL of approximately 2 × 107 cell/mL HCT-116 colon cancer cells suspended in saline were subcutaneously injected into the shoulder. Tumors were allowed to grow for two weeks before imaging and biodistribution studies.

Small-Animal PET/CT imaging

Prior to imaging, animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. 100 µL of 74 kBq/µL 55CoCl2 in saline was injected into HCT-116 tumor bearing mice (n=4) via tail vein injection and imaged using an Inveon MicroPET/CT scanner (Siemens, USA) at 2, 24, and 48 hrs post injection. Static PET images were acquired for 20 minutes. PET data was reconstructed using standard methods with the maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) algorithm and co-registered with CT (computed tomography) using image display software (Inveon Research Workplace Workstation, Siemens, USA). Volumes of Interest (VOI) were drawn using CT anatomical guidelines.

Biodistributions

55Co-NO2A-L19K-FDNB and 55Co-DO3A-L19K-FDNB were prepared and radiolabelled similar to the 64Cu analogues described by Marquez et al. (32) and with a final specific activity of 3.7 MBq/µg. 100 µL of a). 74 kBq/µL 55CoCl2, b). 37 kBq/µL 55Co-NO2A-FDNB, or c). 37 kBq/µL 55Co-DO3A-FDNB in saline were injected into HCT-116 tumor bearing mice. For each agent, (n=3) mice were sacrificed at 24 and 48 hrs post injection followed by removal of blood, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, muscle, fat, heart, brain, bone, tumor, stomach, small intestine (sm int), upper large intestine (u lg int), and lower large intestine (l lg int). Each organ was weighed and measured for radioactivity using a gamma counter. The radioactivity was background subtracted, decay corrected to the time of injection and reported as % ID/g (percent injected dose/g tissue).

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism version 6 (Graphpad, USA) and reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA to compare more than two groups with one variable. P values with 95% confidence interval (P < 0.05) were considered significant.

Results

Production and Purification of High Specific Activity 55Co

58Ni was plated onto a gold disk with an average efficiency of 95 ± 3 % and thickness of ~300µm. Irradiations produced an average of 6 ± 1 MBq 55Co/µAh which is consistent with yields predicted by Kaufman (20) and about 30% lower than yields predicted by Reimer et al. (19). 57Ni and 57Co were co-produced at rates of 16 ± 2 kBq/µAh and 11 ± 2 kBq/µAh respectively and were approximately 25% and 20% lower than yields predicted by Reimer et al. (19) respectively.

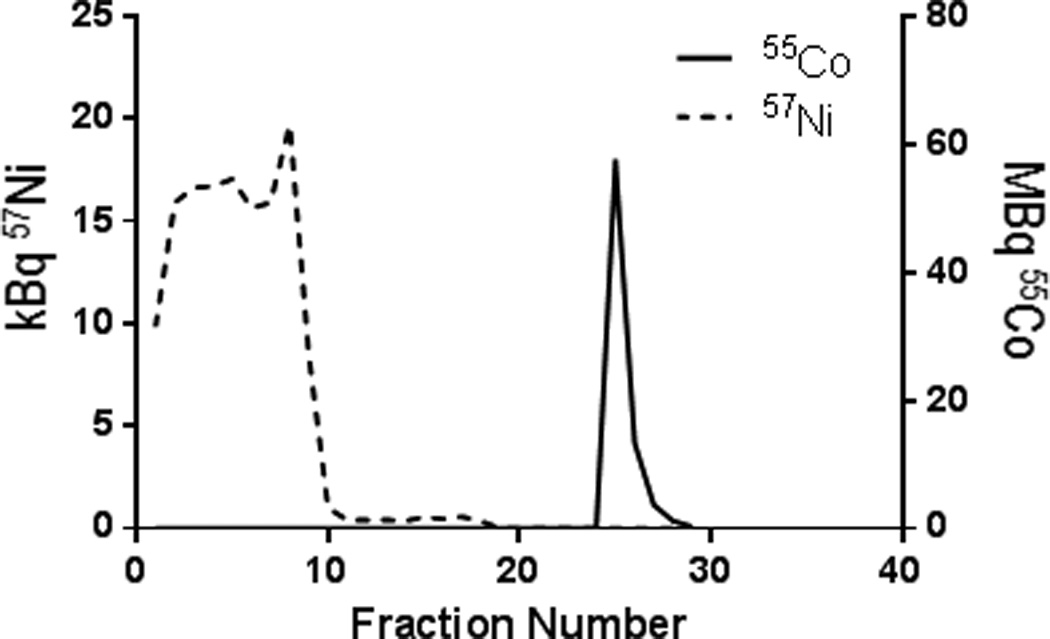

Due to the co-production of 57Ni, separation could be analyzed by measuring the characteristic gamma rays of 57Ni (E1=1.378 MeV, I1=81.7% and E2=0.127 MeV, I2=16.7%) and 55Co (E1=0.931 MeV, I1=75%; E2=0.477 MeV, I2=20.2% and E3=1.409 MeV, I3=16.9%) in each fraction using an HPGe detector. Elution profiles for 57Ni and 55Co are shown in Figure 1. 57Co contamination was determined by analyzing its characteristic gamma ray 0.122 MeV (85.6%) in each fraction. Washing the column with an additional 10–40 mL 9 M HCl removed nickel without significant loss of 55Co. The average recovery of 55Co with a 40 mL 9 M HCl column wash was 92 ± 3 %.

Figure 1.

Concentration of 55Co and 57Ni in each fraction, as measured using HPGe detection of the characteristic gamma rays, showing good separation.

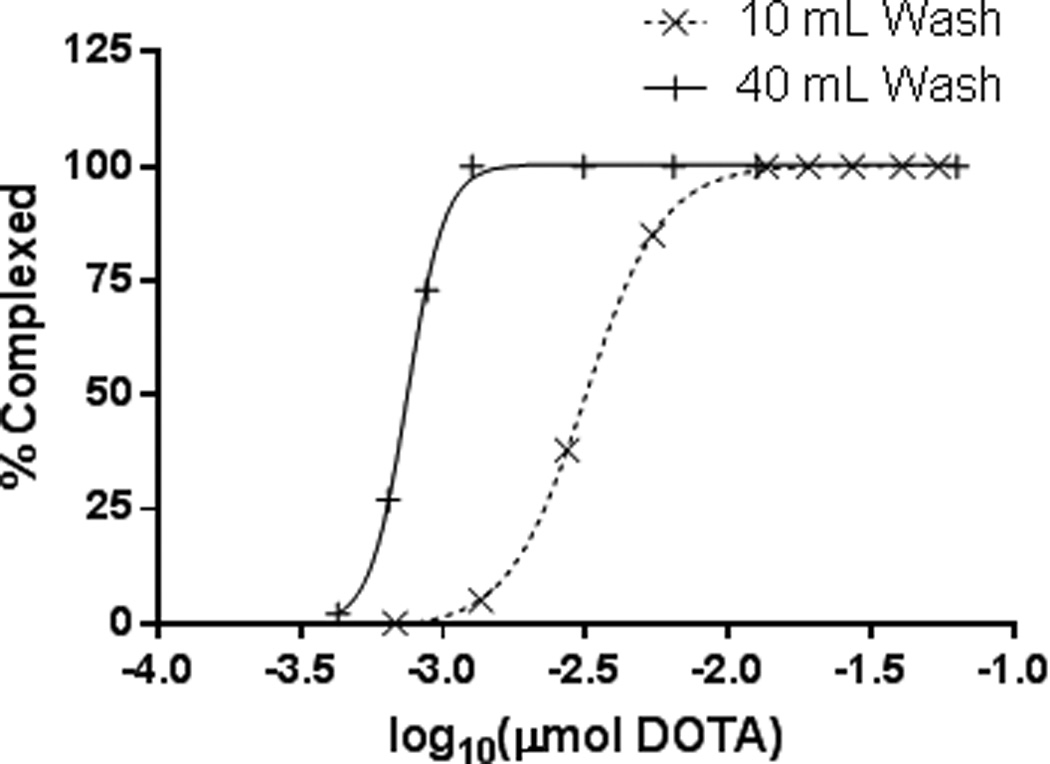

ESA measured via DOTA titration was found to be 259 MBq/µmol DOTA when washing the column with 10 mL 9 M HCl. Increasing the column wash to 40 mL resulted in an increased ESA of 1.96 GBq/µmol DOTA (Figure 2). Ion Chromatography measured nickel concentrations to be 94.6 µmol/MBq and 757 nmol/MBq for 10 mL and 40 mL column washes respectively. The only radioactive impurity found in the final 55Co fraction was 57Co at 0.2 % of the total 55Co activity.

Figure 2.

55Co-DOTA titration curves demonstrating a seven-fold increase in ESA (259 MBq/µmol to 1.96 GBq/µmol) when washing the column with an additional 40 mL 9 M HCl acid versus a 10 mL column wash.

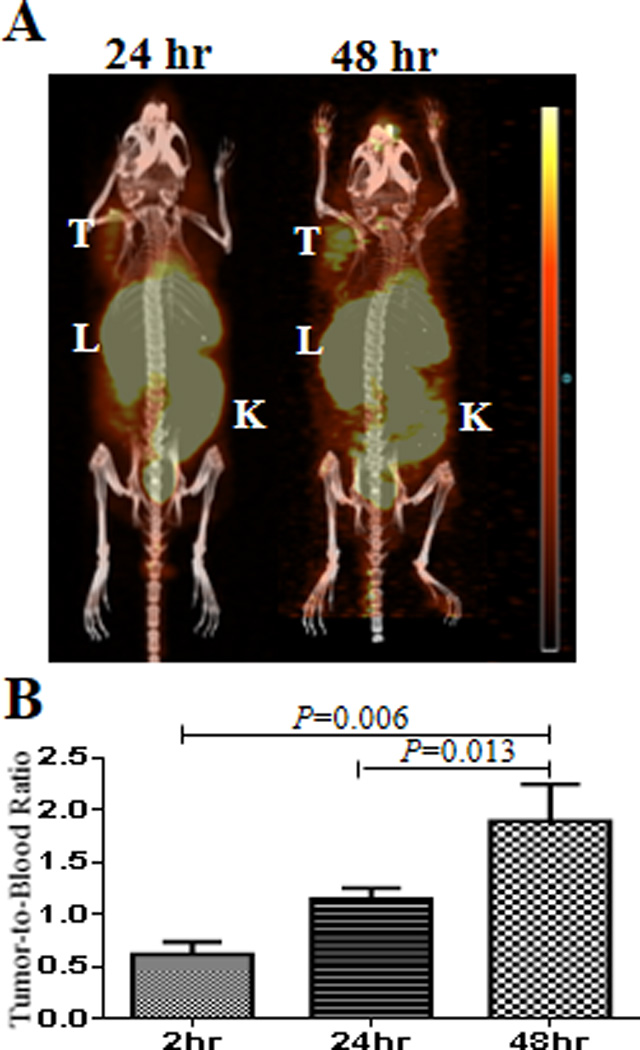

55CoCl2 Small-Animal PET/CT Imaging and Biodistribution

As an emerging radioisotope applicable in oncologic PET imaging, very little data existed about the in vivo stability of different 55Co-chelate complexes. HCT-116 tumor xenografts were imaged (Figure 3A) and post PET biodistribution studies (Table 1) were performed at 2, 24, and 48 hrs p.i. (post injection) to investigate the distribution of free 55CoCl2 in this model. Interestingly, free 55CoCl2 was observed in the tumor at each of these time points. Tumor-to-blood ratios at 2 and 48 hrs were 0.6 ± 0.1 and 1.9 ± 0.4 respectively (P=0.006) exhibiting a 3-fold increase due to fast blood clearance and relatively slow tumor wash out (Figure 3B and Table 1). High uptake in the heart at 2 hrs p.i. could be due to the potential of Co2+ to mimic calcium influx (12, 15). Clearance of free 55CoCl2 occurred through the liver and kidney as indicated by the high uptake values at 2 hrs p.i. followed by about 2-fold consecutive decrease in 55CoCl2 uptake at 24 and 48 hrs p.i. (Table 1).

Figure 3.

24 and 48 hr PET images of 55CoCl2 showing uptake in the tumor and clearance through the liver, kidney, and intestines (A). Tumor-to-blood ratio exhibits a 3-fold increase from 2–48 hrs (B).

Table 1.

Biodistribution data for A) 55CoCl2 2, 24, and 48 hrs p. i., B) 55Co-NO2A-L19K-FDNB 24 and 48 hrs p. i., and C) 55Co-DO3A-L19K-FDNB 24 and 48 hrs p. i.

| 2 hr (%ID/g ± SD) | 24 hr (%ID/g ± SD) | 48 hr (%ID/g ± SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | A | A | B | C | A | B | C |

| Blood | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 1.40 ± 0.04 | 1.57 ± 0.09 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.04 |

| Lung | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.98 ± 0.09 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.03 |

| Liver | 15.7 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Spleen | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| Kidney | 10.5 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 12.6 ± 4.1 | 16.0 ± 3.8 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 5.8 ± 1.2 |

| Muscle | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| Fat | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.30 ± 0.03 |

| Heart | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.33 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| Brain | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Bone | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| Tumor | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.03 |

| Stomach | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| Sm int | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| U lg int | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.03 |

| L lg int | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

Stability of 55Co-Chelate Complexes

The stability of radiometal-chelate combinations is crucial when designing new PET imaging probes. Complexes that are not stable in vivo can lead to the radiometal decomplexing from the chelate and accumulating in different organs throughout the body, increasing background signal and dose to non-target organs. The longer blood clearance associated with the L19K-FDNB peptide which we chose as our model system to investigate 55Co, allows for the potential decomplexation of 55Co-chelate complexes to be measured at clinically relevant time points in order to evaluate the in vivo stability of these complexes. It has previously been established that changing the radiometal on peptides can have a drastic effect on the affinity of the peptide to its receptor (35). Using 55Co to radiolabel the NO2A- or DO3A-peptides dramatically decreased the affinity for their tumor-associated target, VEGF, (32) as shown by their reduced tumor uptake compared with the 64Cu-labeled analog, which was radiolabelled at the same specific activity (supplementary Figure S1).

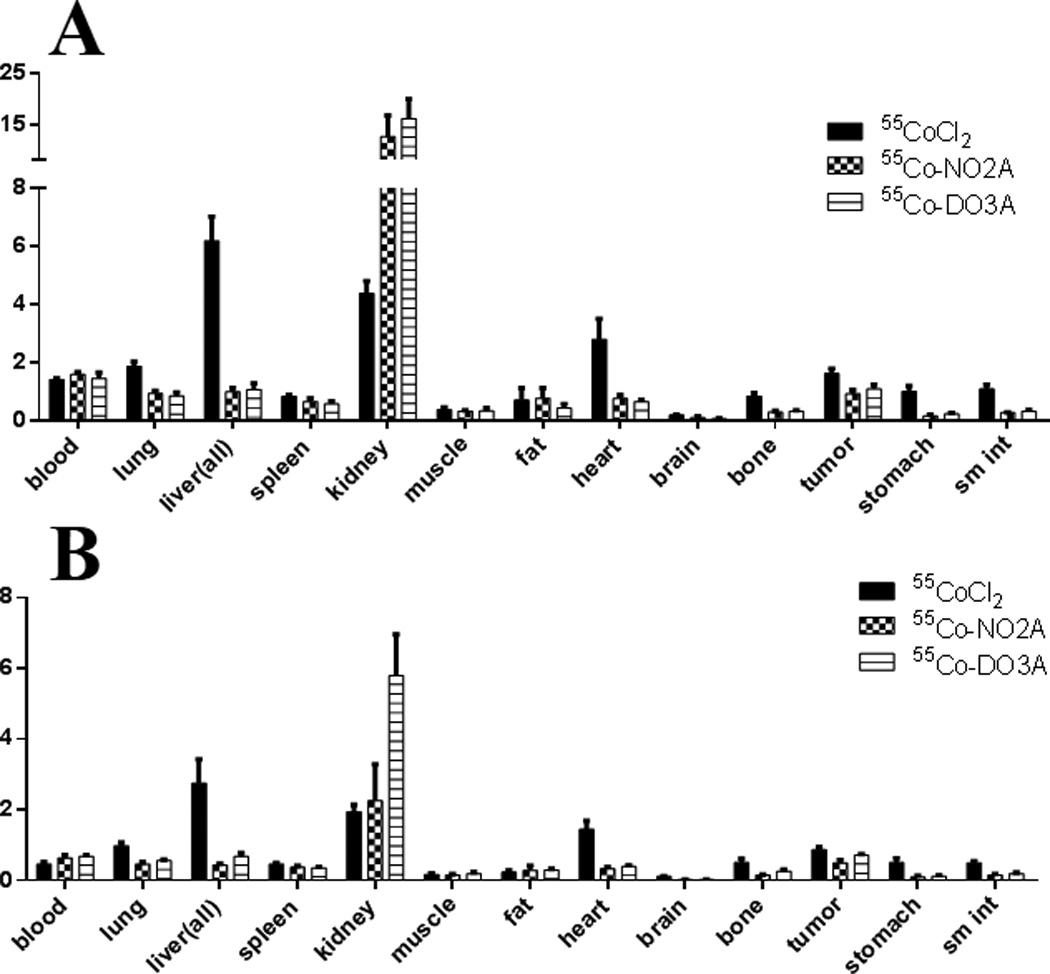

The 24 and 48 hr biodistribution studies of 55Co-NO2A-L19K-FDNB and 55Co-DO3A-L19K-FDNB were compared with free 55CoCl2 (Table 1). These data show that both NO2A and DO3A chelates radiolabelled with 55Co exhibit good in vivo stability, as shown by their low uptake in the liver, lung, heart, bone, stomach, and small intestine compared with the high uptake of free 55CoCl2 in these organs. The difference in uptake is most notable in the liver, where the 55Co-labelled peptides had a 6-fold lower uptake than free 55CoCl2 at 24 and 48 hrs. 55Co-labelled peptides had a 4-fold lower uptake than free 55CoCl2 in the heart at 24 hrs and a 7-fold lower uptake at 48 hrs. While the affinity of this particular peptide was negatively affected by radiolabelling with 55Co, this study shows that DOTA and NOTA-derived chelates form stable complexes with 55Co in vivo and may be used to investigate other probes which are insensitive to changes in radiometals.

Discussion

The 58Ni(p,α)55Co reaction is an effective route for producing high specific activity 55Co. Previously this method was reported using a copper disk (18) as opposed to gold, however using copper as the target backing material could have a negative effect on the effective specific activity as copper has a high affinity to both NOTA and DOTA chelators and would compete with 55Co for binding. The downside to this reaction is that it has a lower cross section when compared with other radiometals such as 64Cu and 89Zr, which may limit the availability of this isotope to facilities that have solid target cyclotron capabilities.

The biodistribution of 55CoCl2 is comparable to that previously observed for 64CuCl2, as both metals are divalent cations and may have similar interactions with transport proteins in vivo (36–40). The tumor uptake of 55Co is interesting and warrants further investigation. It is possible that its uptake is due to the overexpression of calcium ion channels often found in cancer cells (41). Several studies have shown the uptake of 55CoCl2 in ischemic cells and this is believed to be due to 55Co partially mirroring calcium influx (12, 15).

The in vivo stability of the NOTA and DOTA analogs, NO2A and DO3A, complexed with 55Co provides the foundation for developing 55Co labelled peptides, antibodies, nanoparticles and small molecules. 55Co-NOTA and 55Co-DOTA complexes have significantly lower liver uptake when compared to 64Cu-NOTA and 64Cu-DOTA complexes (Figure 4) (7, 42) which could be beneficial in cases where reduced background signal is desired i.e. liver metastases. The lower liver uptake observed with the 55Co complexes implies that the transchelation problem that exists with 64Cu (42–44) is greatly reduced with the use of 55Co. This reduction in transchelation for the cobalt complexes in agreement with the transfer half-life of 800 hours for Co from Co(DOTATOC) in human blood serum measured by Heppler et al. (7). Additionally the high positron branching ratio (4 times that of 64Cu and 3 times that of 89Zr) leads to similar images with a lower amount of radioactivity administered. One drawback, however, is the higher dose to non-target tissue from the additional gamma rays present from the decay of 55Co.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the 24 hr (A) and 48 hr (B) biodistributions of 55CoCl2 with 55Co-NO2A-FDNB and 55Co-DO3A-FDNB exhibiting the in vivo stability of 55Co-NO2A and 55Co-DO3A complexes.

Since the affinity of some peptides is dependent on the attached radiometal it would be interesting to examine this effect on different peptide models. The anti-VEGF peptide used in this work exhibited lower tumor uptake than previously measured with 64Cu (Supplementary Figure S1), however in work done by Heppler et al. (7) 55Co-DOTATOC showed higher affinity for the somatostatin type two receptor than any other radiometals measured. These different studies imply that 55Co may also coordinate with the peptide probe concurrently with the chelate in order to elicit a change in the peptide’s affinity for its target. Therefore, determining the structure-activity relationship of these peptide-chelate-metal complexes would be significant for designing superior PET imaging probes.

Conclusions

55Co can be made with high specific activity via the 58Ni(p,α)55Co reaction. The in vivo stability of 55Co labeled NOTA and DOTA derivatives make this radioisotope a promising isotope for many different applications. Future work should compare the affinity of 55Co labeled peptides with other radiometals to optimize the best metal-chelate-peptide combination for the application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patricia Margenau and Bill Margenau for operation of the CS15 cyclotron. The studies presented in this work were conducted in the MIR Pre-Clinical Pet-CT Facility of the Washington University School of Medicine. This work was performed with the support from the Siteman Cancer Center Small Animal Imaging Core. This work was supported in part by Department of Energy grant number DESC0007352.

References

- 1.Ikotun OF, Lapi SE. The rise of metal radionuclides in medical imaging: copper-64, zirconium-89 and yttrium-86. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;3:599–621. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brasse D, Nonat A. Radiometals: towards a new success story in nuclear imaging? Dalton Trans. 2014 doi: 10.1039/c4dt02911a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CJ, Ferdani R. Copper-64 radiopharmaceuticals for PET imaging of cancer: advances in preclinical and clinical research. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:379–393. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkers EC, Oude Munnink TH, Kosterink JG, et al. Biodistribution of 89Zr-trastuzumab and PET imaging of HER2-positive lesions in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:586–592. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrosini V, Campana D, Bodei L, et al. 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT clinical impact in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:669–673. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirzaii M, Kakavand T, Talebi M, Rajabifar S. Electrodeposition iron target for the cyclotron production of Co-55 in labeling proteins. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 2012;292:261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heppeler A, Andre JP, Buschmann I, et al. Metal-ion-dependent biological properties of a chelator-derived somatostatin analogue for tumour targeting. Chemistry-a European Journal. 2008;14:3026–3034. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thisgaard H, Olesen ML, Dam JH. Radiosynthesis of Co-55- and Co-58m-labelled DOTATOC for positron emission tomography imaging and targeted radionuclide therapy. Journal of Labelled Compounds & Radiopharmaceuticals. 2011;54:758–762. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goethals P, Volkaert A, Vandewielle C, Dierckx R, Lameire N. Co-55-EDTA for renal imaging using positron emission tomography (PET): A feasibility study. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2000;27:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karanikas G, Schmaljohann J, Rodrigues M, Chehne F, Granegger S, Sinzinger H. Examination of Co-complexes for radiolabeling of platelets in positron emission tomographic studies. Thrombosis Research. 1999;94:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira CL, Lapi S, Steele J, et al. (55)Cobalt complexes with pendant carbohydrates as potential PET imaging agents. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2007;65:1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Reuck J, Santens P, Keppens J, et al. Cobalt-55 positron emission tomography in recurrent ischaemic stroke. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 1999;101:15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(98)00076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens H, Jansen HML, De Reuck J, et al. (55)Cobalt (Co) as a PET-tracer in stroke, compared with blood flow, oxygen metabolism, blood volume and gadolinium-MRI. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1999;171:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Reuck J, Santens P, Strijckmans K, Lemahieu I. Related ETFA. Cobalt-55 positron emission tomography in vascular dementia: significance of white matter changes. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2001;193:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Reuck J, Stevens H, Jansen H, et al. The significance of cobalt-55 positron emission tomography in ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;8:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(99)80034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Reuck J, Vonck K, Santens P, et al. Cobalt-55 positron emission tomography in late-onset epileptic seizures after thrombo-embolic middle cerebral artery infarction. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2000;181:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkman GA, Helmer J, Lindner L. Nickel and Copper Foils as Monitors for Cyclotron Beam Intensities. Radiochemical and Radioanalytical Letters. 1977;28:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spellerberg S, Reimer P, Blessing G, Coenen HH, Qaim SM. Production of (55)Co and (57)Co via proton induced reactions on highly enriched (58)Ni. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1998;49:1519–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reimer P, Qaim SM. Excitation functions of proton induced reactions on highly enriched Ni-58 with special relevance to the production of Co-55 and Co-57. Radiochimica Acta. 1998;80:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman S. Reactions of Protons with 58-Nickel and 60-Nickel. Physical Review. 1960;117:1532–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Abyad M, Comsan MN, Qaim SM. Excitation functions of proton-induced reactions on natFe and enriched 57Fe with particular reference to the production of 57Co. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins IL, Wain AG. Excitation Functions for Bombardment of Fe-56 with Protons. Journal of Inorganic & Nuclear Chemistry. 1970;32:1419-&. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma H, Zweit J, Smith AM, Downey S. Production of Cobalt-55, a Short-Lived, Positron Emitting Radiolabel for Bleomycin. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1986;37:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(86)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coetzee PP, Peisach M. Activation Cross-Sections for Dueteron-Induced Reactions on Some Elements of First Transition Series, up to 5,5mev. Radiochimica Acta. 1972;17:1-&. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zavorka L, Simeckova E, Honusek M, Katovsky K. The Activation of Fe by Deuterons at Energies up to 20 MeV. Journal of the Korean Physical Society. 2011;59:1961–1964. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastren T, Sultan D, Lapi SE. Production And Separation Of Co-55 Via The Ni-58(p,alpha)Co-55 Reaction. 14th International Workshop on Targetry and Target Chemistry. 2012;1509:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdovinos HF, Graves S, Barnhart T, Nickles RJ. Co-55 Separation From Proton Irradiated Metallic Nickel. Xiii Mexican Symposium on Medical Physics. 2014;1626:217–220. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastren T, Guthrie J, Eisenbeis P, et al. Specific activity measurement of (6)(4)Cu: a comparison of methods. Appl Radiat Isot. 2014;90:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng D, Anderson CJ. Rapid and sensitive LC-MS approach to quantify non-radioactive transition metal impurities in metal radionuclides. Chem Commun (Camb) 2013;49:2697–2699. doi: 10.1039/c3cc39071c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Kovacs Z. The synthesis and chelation chemistry of DOTA-peptide conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:391–402. doi: 10.1021/bc700328s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Studer M, Meares CF. Synthesis of novel 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N',N"-triacetic acid derivatives suitable for protein labeling. Bioconjug Chem. 1992;3:337–341. doi: 10.1021/bc00016a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marquez BV, Ikotun O, Meares CF, Lapi SE. Development of a Radiolabeled Irreversible Peptide (RIP) as a PET Imaging Agent for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Journal of Labelled Compounds & Radiopharmaceuticals. 2013;56:S86–S86. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy DW, Shefer RE, Klinkowstein RE, et al. Efficient production of high specific activity Cu-64 using a biomedical cyclotron. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 1997;24:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szelecsenyi F, Blessing G, Qaim SM. Excitation-Functions of Proton-Induced Nuclear-Reactions on Enriched Ni-61 and Ni-64 - Possibility of Production of No-Carrier-Added Cu-61 and Cu-64 at a Small Cyclotron. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1993;44:575–580. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ginj M, Maecke HR. Radiometals or Interest for Peptide Labeling and Labeling Approaches. In: Sigel H, editor. Metal Ions in Biological Systems: Volume 42: Metal Complexes in Tumor Diagnosis and as Anticancer Agents. Vol. 42. CRC Press; 2004. p. 600. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen JT, Persson M, Madsen J, Kjaer A. High tumor uptake of Cu-64: Implications for molecular imaging of tumor characteristics with copper-based PET tracers. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2013;40:345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang HY, Cai HW, Lu X, Muzik O, Peng FY. Positron Emission Tomography of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Xenografts in Mice Using Copper (II)-64 Chloride as a Tracer. Academic Radiology. 2011;18:1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin CX, Liu HG, Chen K, et al. Theranostics of Malignant Melanoma with (CuCl2)-Cu-64. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;55:812–817. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.133850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KI, Jang SJ, Park JH, et al. Detection of Increased 64Cu Uptake by Human Copper Transporter 1 Gene Overexpression Using PET with 64CuCl2 in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Model. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1692–1698. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.141127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng FY, Lutsenko S, Sun XK, Muzik O. Positron Emission Tomography of Copper Metabolism in the Atp7b(−/−) Knock-out Mouse Model of Wilson's Disease. Molecular Imaging and Biology. 2012;14:70–78. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0476-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li M, Xiong Z-G. Ion channels as targets for cancer therapy. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacology. 2011;3:156–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression with a 64Cu-labeled monoclonal antibody: NOTA is superior to DOTA. Plos One. 2011;6:e28005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar SR, Gallazzi FA, Ferdani R, Anderson CJ, Quinn TP, Deutscher SL. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of (6)(4)Cu-radiolabeled KCCYSL peptides for targeting epidermal growth factor receptor-2 in breast carcinomas. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2010;25:693–703. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bass LA, Wang M, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. In vivo transchelation of copper-64 from TETA-octreotide to superoxide dismutase in rat liver. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:527–532. doi: 10.1021/bc990167l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.