Abstract

A few studies have assessed the effects of fat intake in the induction of dyspeptic symptoms. So, the aim of this study was to review the articles regarding the dietary fat intake and FD. We used electronic database of PubMed to search. These key words were chosen: FD, dietary fat, dyspeptic symptom, energy intake and nutrients. First, articles that their title and abstract were related to the mentioned subject were gathered. Then, full texts of related articles were selected for reading. Finally, by excluding four articles that was irrelevant to subject, 19 relevant English papers by designing clinical trial, cross-sectional, case–control, prospective cohort, and review that published from 1992 to 2012 were investigated. Anecdotally, specific food items or food groups, particularly fatty foods have been related to dyspepsia. Laboratory studies have shown that the addition of fat to a meal resulted in more symptoms of fullness, bloating, and nausea in dyspeptic patients. Studies have reported that hypersensitivity of the stomach to postprandial distension is an essential factor in the generation of dyspeptic symptoms. Small intestinal infusions of nutrients, particularly fat, exacerbate this hypersensitivity. Moreover, evidence showed that perception of gastric distension increased by lipids but not by glucose. Long chain triglycerides appear to be more potent than medium chain triglycerides in inducing symptoms of fullness, nausea, and suppression of hunger. Thus, Fatty foods may exacerbate dyspeptic symptoms. Therefore, it seems that a reduction in intake of fatty foods may useful, although this requires more evaluations.

Keywords: Dietary fat, dyspeptic symptom, energy intake, functional dyspepsia

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common disorder that is, determined with persistent, or recurrent upper gastrointestinal symptoms.[1,2] These symptoms including epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, inability to finish a normal-sized meal, early satiation, anorexia, belching, nausea and vomiting, upper abdominal bloating, and even heartburn and regurgitation.[1,3,4] The prevalence of dyspepsia depending on the different definitions that have been used and geographical area features has been reported between 20% and 30% worldwide. FD prevalence also seems to be high in Iran, ranging from 0.1% to 29.9%.[5]

The pathophysiology and etiology of FD have been under assessment and are poorly identified. Mechanisms that have been proposed include delayed gastric emptying, visceral hypersensitivity to distension, impaired gastric accommodation to meal, Helicobacter pylori infection, abnormal duodenojejunal motility, hypersensitivity to lipids or acid in the duodenum, or central nervous system dysfunction.[6,7,8] Many patients mentioned their symptoms to be related to the different kinds of food consumption.[9]

Functional dyspeptic patients frequently have reported that their symptoms aggravate with ingestion of high-fat foods.[3] Laboratory studies have shown that intraduodenal infusion of lipid, but not glucose, resulted in more symptoms of fullness, bloating, and nausea in FD patients.[9,10]

The pathophysiological mechanisms of high-fat foods in induction of dyspeptic symptoms are not completely understood.[6] A review of controlled double-blind randomized studies has determined the most important effective factor in pathophysiology of fat-induced dyspeptic symptoms. This review has shown that cholecystokinin (CCK) is a major factor that mediates the effects of lipid on gastrointestinal sensations. The studies have indicated that during distension of the stomach, lipids are a main trigger of dyspeptic symptoms such as nausea, bloating, pain, fullness, and other related symptoms.[11] Since almost all patients with FD associate their symptoms to high-fat foods, they may avoid intake of good source of dietary fat. The evidence have shown that fish and olive oil that are source of n = 3 fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid improve insulin resistance, risk of inflammatory diseases, and other chronic diseases.[12] On the other hand, studies have reported that higher consumption of trans fats is related to higher risk of metabolic syndrome and ischemic heart diseases.[13,14,15,16] However, the investigations suggest that a reduction in fatty foods intake may be beneficial in controlling symptoms of dyspepsia.[10] In this regard, a systematic review of the literature relating to food intake and FD proposed that fatty foods may be effective in induction of FD symptoms.[17] Large-scale studies are required to investigate the role of fat and other macronutrient intake in triggering symptoms of FD. Therefore, the aim of this review article is to evaluate the relationship between dietary fat intake and FD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, electronic database of PubMed was used to search. These key words were chosen: FD, dietary fat, dyspeptic symptom, energy intake, and nutrients. Relevant English papers with design of trial, cross-sectional, case–control, prospective cohort and review studies that were published from 1992 to 2012 were selected. We also reviewed the reference lists of the related publications to recognize additional studies.

RESULTS

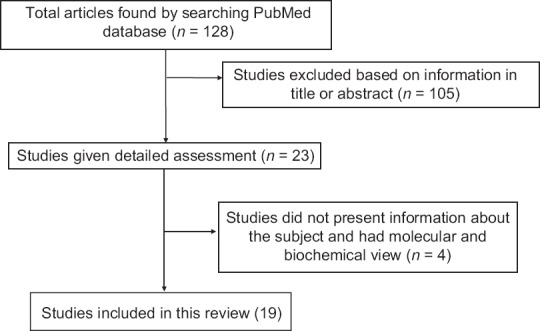

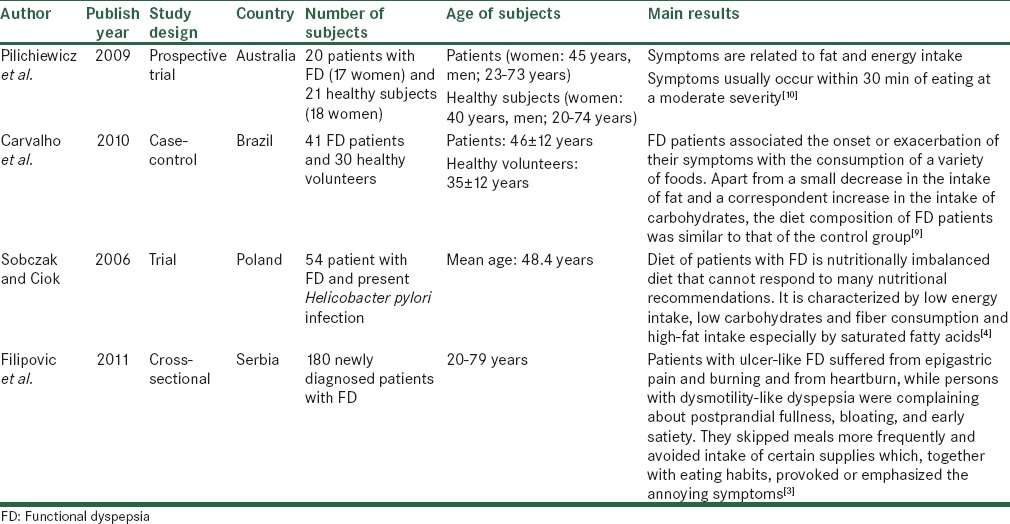

We found 128 English published papers. First, we read the title of all gathered articles and selected those that were related to the subject. In the next step, by reading abstract of selected articles, 23 related articles were chosen for reading their full text. If the title and abstract of chosen articles were not relevant to the subject, the articles were excluded from the study. We excluded four article because some of them had molecular and biochemical view and were irrelevant to subject. Thus, our review article included 19 studies. The flowchart for selection of articles is given in Figure 1. We have also summarized the most important studies reviewed in the current paper in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selection of articles

Table 1.

Some of the investigated studies in present article

Fat intake and hypersensitivity to gastric distention

The pathophysiology of FD is not completely understood. Different mechanisms have been proposed. Hypersensitivity of the stomach to distension is an essential factor in induction of dyspeptic symptom. The prevalence of hypersensitivity to gastric distention is reported to be around 35% among dyspeptic patients.[10,18] This disorder is related to dyspeptic symptoms such as postprandial pain, belching, and weight loss. Dyspeptic patients have frequently reported intolerance to high-fat foods.[11] These patients can only eat small meals. Enhanced sensitivity to gastric distention is shown to reduce the tolerance of volume/pressure. This finding is approved by laboratory studies.[10]

Previous evidence showed the association between dyspeptic symptoms and food intake. Reports indicated that fullness and bloating are related to fat intake. Laboratory studies have shown that duodenal infusion of fat lead to enhancement of sensitivity to gastric distention and worsening of symptom in patients. In contrast, glucose infusion resulted in reduction in gastric sensitivity in dyspeptic patients. The reports have shown a particular role for fatty food in the induction of symptoms.[10] In another study, postprandial fullness was the main complaint that linked to high-fat content foods. Fat ingestion, which can delay gastric emptying, may induce disturbances in gastric motility and causing postprandial fullness in dyspeptic patients.[9]

Several studies have indicated that regulatory performance of fat on gastrointestinal sensitivity may be mediated by CCK release. These studies have shown that dexloxiglumide, CCK-A receptor antagonists, can relief developed symptoms by duodenal lipid infusion and gastric distention.[19] Therefore, lipids in addition to their effects on gastrointestinal function, by releasing CCK play the main role in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia.[19]

Fat and gastrointestinal hormones

Patients with FD believe that their symptoms are related to ingestion of a variety of food items especially fatty foods. The mechanisms by which dietary fat induces dyspeptic symptoms are not completely understood.[19]

Studies have shown that lipids regulate the function of the upper gastrointestinal such as gastric emptying, stimulate the pancreaticobiliary secretion, and gastric acid secretion.[19] Fat by releasing CCK may play an important role in gastric perception and appearance of symptoms.[11] Fat intake is related to stimulation and secretion of gastrointestinal hormones such as CCK and glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and polypeptide Y. Evidence has indicated that these peptides modulate gastric emptying and are effective in the induction of dyspeptic symptoms.[10] Intravenous injection of CCK and GLP-1 induced nausea in healthy subjects. Higher scores for nausea and pain have been reported in higher concentration of CCK.[10] Fatty foods usually increase the fasting and postprandial CCK concentration in patients compared to healthy subjects.[10] The results of a cohort study did not show any difference in CCK stimulation by duodenal lipid among patients and healthy subjects. However, dyspeptic symptoms were different between them considerably. This difference may be due to differences in the responses of CCK receptors in both groups.[19] Studies have shown that intravenous injection of CCK antagonist, dexloxiglumide, decrease symptoms induced by duodenal lipid infusion. However, this factor alone is not responsible for the dyspeptic symptoms, and other factors are likely effective. Thus, the role of fat intake in the induction of dyspeptic symptoms requires further evaluations.[19]

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have reported that some kinds of foods such as chili, fructose, and fatty meal compared to other foods may exacerbate dyspeptic symptoms. Although dyspepsia is a common disease, and many patients have reported that their symptoms are associated with fatty foods, a limited number of studies have investigated the relationship between dietary factors, especially dietary fat and dyspepsia.[4] The mechanisms by which dietary factors cause dyspeptic symptoms are not entirely clear. However, the investigations showed that diet plays an important role in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia through different mechanisms such as abnormalities in gastric emptying and intragastric meal distribution, gastric or small intestinal hypersensitivity, gastric acid hypersecretion, and alterations in the secretion of gastrointestinal hormone.[9,18] Hypersensitivity to gastric distention and chemical stimuli such as nutrient (fat), acid and gastrointestinal hormones (CCK), and interaction between them have an essential role in the induction of symptomatic response.[19]

Laboratory studies have confirmed that nutrient hypersensitivity may be specific for fat because duodenal injection of glucose had not any effect on dyspeptic symptoms.[19] The assessments have shown that fullness and bloating which are caused by the high-fat meal occur 30 min after fat ingestion.[10] CCK release may be representing this effect of fatty foods. A review on a series of controlled double-blind randomized studies shows that CCK release is a main mediator of sensation of dyspeptic symptoms by fatty food in both patients and healthy subjects. Furthermore, evidence has indicated that long chain triglycerides (LCTs) are greater strong than medium chain triglycerides (MCTs) in induction of symptoms such as fullness, nausea, and suppression of hunger. This effect of LCTs is attributed to CCK release while MCTs do not cause CCK release. Fatty acids that are created from digestion of triglycerides but no indigestible fat can only influence on gastrointestinal motility, hormone secretion, appetite suppression, gastrointestinal perception, and induce symptomatic response. Although more investigation and designing large cohort studies are required to identify the relationship between fat intake and dyspepsia, current studies show that fatty foods are associated with occurrence of dyspeptic symptoms and reduction of fat intake may alleviate symptoms among patients with FD.[11]

CONCLUSION

The pathophysiology of FD is not completely understood. Although most patients associate their dyspeptic symptoms to food ingestion especially fatty foods, the assessment of the relationship between dietary fat and dyspeptic symptoms has been limited to a few studies. Studies show that fatty foods are associated with the occurrence of dyspeptic symptoms, and lower fat intake may alleviate symptoms in patients. Therefore, large-scale studies are required to evaluate the impact of dietary factors on symptoms and the role of dietary intervention particularly low-fat diet as a therapeutic strategy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goswami BD, Phukan C. Clinical features of functional dyspepsia. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60(Suppl):21–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanghellini V, Ghidini C, Maccarini MR, Paparo GF, Corinaldesi R, Barbara L. Fasting and postprandial gastrointestinal motility in ulcer and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Gut. 1992;33:184–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filipovic BF, Randjelovic T, Kovacevic N, Milinic N, Markovic O, Gajic M, et al. Laboratory parameters and nutritional status in patients with functional dyspepsia. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:300–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobczak M, Ciok J. Evaluation of nutritional habits in patients with functional dyspepsia before and after Helicobacter pylori eradiaction. Gastroenterol Pol. 2006;13:443–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amini E, Keshteli AH, Jazi MS, Jahangiri P, Adibi P. Dyspepsia in Iran: SEPAHAN systematic review no 3. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:S18–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tack J, Caenepeel P, Piessevaux H, Cuomo R, Janssens J. Assessment of meal induced gastric accommodation by a satiety drinking test in health and in severe functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2003;52:1271–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brun R, Kuo B. Functional dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:145–64. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10362639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bortolotti M, Coccia G. The treatment of functional dyspepsia with red pepper. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:947–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200203213461219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvalho RV, Lorena SL, Almeida JR, Mesquita MA. Food intolerance, diet composition, and eating patterns in functional dyspepsia patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:60–5. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilichiewicz AN, Horowitz M, Holtmann GJ, Talley NJ, Feinle-Bisset C. Relationship between symptoms and dietary patterns in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried M, Feinle C. The role of fat and cholecystokinin in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2002;51(Suppl 1):i54–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azadbakht L, Rouhani MH, Surkan PJ. Omega-3 fatty acids, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1259–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Fast foods and risk of chronic diseases. J Res Med Sci. 2008;13:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shafaeizadeh S, Jamalian J, Owji AA, Azadbakht L, Ramezani R, Karbalaei N, et al. The effect of consuming oxidized oil supplemented with fiber on lipid profiles in rat model. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1541–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asgary S, Nazari B, Sarrafzadegan N, Saberi S, Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A. Fatty acid composition of commercially available Iranian edible oils. J Res Med Sci. 2009;14:211–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Home use of vegetable oils, markers of systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction among women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:913–21. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinle-Bisset C, Vozzo R, Horowitz M, Talley NJ. Diet, food intake, and disturbed physiology in the pathogenesis of symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:170–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tack J, Bisschops R, DeMarchi B. Causes and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3:503–8. doi: 10.1007/s11894-001-0071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinle-Bisset C, Horowitz M. Dietary factors in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:608–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]