Abstract

Mitochondrial disorders are clinically and genetically diverse, with mutations in mitochondrial or nuclear genes able to cause defects in mitochondrial gene expression. Recently, mutations in several genes encoding factors involved in mt-tRNA processing have been identified to cause mitochondrial disease. Using whole-exome sequencing, we identified mutations in TRMT10C (encoding the mitochondrial RNase P protein 1 [MRPP1]) in two unrelated individuals who presented at birth with lactic acidosis, hypotonia, feeding difficulties, and deafness. Both individuals died at 5 months after respiratory failure. MRPP1, along with MRPP2 and MRPP3, form the mitochondrial ribonuclease P (mt-RNase P) complex that cleaves the 5′ ends of mt-tRNAs from polycistronic precursor transcripts. Additionally, a stable complex of MRPP1 and MRPP2 has m1R9 methyltransferase activity, which methylates mt-tRNAs at position 9 and is vital for folding mt-tRNAs into their correct tertiary structures. Analyses of fibroblasts from affected individuals harboring TRMT10C missense variants revealed decreased protein levels of MRPP1 and an increase in mt-RNA precursors indicative of impaired mt-RNA processing and defective mitochondrial protein synthesis. The pathogenicity of the detected variants—compound heterozygous c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) and c.814A>G (p.Thr272Ala) changes in subject 1 and a homozygous c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) variant in subject 2—was validated by the functional rescue of mt-RNA processing and mitochondrial protein synthesis defects after lentiviral transduction of wild-type TRMT10C. Our study suggests that these variants affect MRPP1 protein stability and mt-tRNA processing without affecting m1R9 methyltransferase activity, identifying mutations in TRMT10C as a cause of mitochondrial disease and highlighting the importance of RNA processing for correct mitochondrial function.

Main Text

Mitochondrial respiratory chain deficiencies lead to insufficient ATP production from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), resulting in a wide range of clinical presentations broadly recognized as “mitochondrial disorders.” Mitochondrial diseases are genetically diverse, owing to the necessary expression, co-ordination, and activity of factors encoded by both the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes for proper mitochondrial function. The 16.6 kb human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) encodes only 22 tRNAs, 2 rRNAs, and 13 polypeptides that are essential components of four of the five OXPHOS complexes.1 The remaining subunits of the respiratory complexes and all of the factors involved in mtDNA expression and maintenance are encoded by the nuclear genome, synthesized in the cytosol, and imported into mitochondria. Thus, there are a large number of potential genetic causes of mitochondrial disease, which has often complicated attempts to identify the correct genetic diagnosis. The advent of next generation sequencing has greatly expanded the list of known gene mutations associated with mitochondrial disease,2 including several genes involved in mitochondrial (mt)-tRNA processing and maturation.3, 4

In mammalian mitochondria, all mt-tRNAs required for mitochondrial protein synthesis are encoded by the mitochondrial genome. Transcription of mtDNA produces long polycistronic transcripts that require further processing. Most mitochondrial open reading frames are separated by at least one mt-tRNA gene, with the structure of mt-tRNAs acting as “punctuation” marks in the transcript5 prior to mt-tRNAs being excised at the 5′ end by the RNase P complex and at the 3′ end by the RNase Z enzyme. The mitochondrial RNase P in animals is composed of three proteins, MRPP1, MRPP2, and MRPP36 (encoded by TRMT10C [MIM: 615423], HSD17B10 [MIM: 300256], and KIAA0391 [MIM: 609947], respectively), whereas RNase Z is encoded by a single gene, ELAC2 (MIM: 605367).7, 8, 9, 10 In addition to cleavage from the polycistronic transcripts, mt-tRNAs undergo many further modifications, with at least 30 different modified residues reported.3, 11 One crucial modification is m1R9 methylation, which is probably important for the correct folding of most mt-tRNAs. In the case of mt-tRNALys, the unmodified in vitro transcript folds into an extended bulged hairpin,12 but with the sole modification of N1 methylation of adenosine 9 (m1A9), the tRNA adopts the classic cloverleaf structure.13 It has been demonstrated that MRPP1 and MRPP2 can form a stable sub-complex that is active as a methyltransferase and is uniquely able to methylate both adenosine and guanine nucleotides at position 9.7, 14 19 of the 22 mt-tRNAs contain either A or G at position 9 and it is likely that all of these are subject to m1R9 methylation.7, 11, 14

We studied two children with suspected mitochondrial disease from unrelated families. Subject 1 (male) was the second child of healthy, non-consanguineous, white British parents, with a healthy older sister. He was born at term by a normal vaginal delivery after a normal pregnancy with a birth weight of 3.7 kg. He did not require resuscitation but was noted to be hypotonic and weak soon after birth. He fed poorly and gained weight slowly, partly due to gastro-esophageal reflux. Neonatal screening revealed significant hearing impairment subsequently confirmed to be sensorineural deafness. He was also found to have a raised plasma alanine transaminase of 439 U/L (normal range 4–45 U/L). Blood lactate levels ranged from 5 to 10 mmol/L (normal range 0.7–2.1 mmol/L) and his CSF lactate level was also elevated at 4.8 mmol/L. Ophthalmological examination, echocardiography, and an MRI were all normal, though the latter was of poor quality. There was a clinical suspicion of craniosynostosis and a lateral skull X-ray appeared to show fused sutures but no further investigations were undertaken. Ultrasound of the kidneys was normal. Blood spot acylcarnitine analysis and plasma biotinidase were normal, plasma amino acid analysis was normal with the exception of a raised alanine concentration, and urine organic acid analysis was normal apart from a raised lactate concentration. He deteriorated rapidly, requiring tube feeding, and at the age of 4 months suffered rhinovirus bronchiolitis requiring ventilatory support with CPAP. It proved impossible to wean him off ventilatory support and he died at 5.5 months of age after withdrawal of this support.

Subject 2 (female) was the second child of unrelated parents of Kurdish origin with a healthy older brother. She was born at term by caesarean delivery, after a normal pregnancy, weighing 3.05 kg. Hypotonia, poor sucking, and feeding difficulties were evident from early in the neonatal period and hyperlactatemia (7.4 mmol/L; normal range 0.90–1.70 mmol/L) with a high lactate to pyruvate ratio (170; normal range 30–50) was recorded at 1 month. She gained weight poorly and nasogastric feeding was commenced at 3 months. At 3.5 months, echocardiography demonstrated left ventricular hypertrophy and lumbar puncture revealed elevated CSF lactate (3.1 mmol/L; control < 2.2 mmol/L). She also had significantly impaired liver function (AST: 84 UI/L, normal range 15–60; ALT: 52 UI/L, normal range 7–40; gGT: 262 UI/L, normal range 6–25 UI/L). Brain MRI was undertaken at 2 months of age and was of poor quality but showed findings suggestive of bifrontal polymicrogyria. Acoustic oto-emissions were abnormal at 4 months, suggesting deafness. Unfortunately, auditory evoked potential was not done. She died at 5 months of age from respiratory distress.

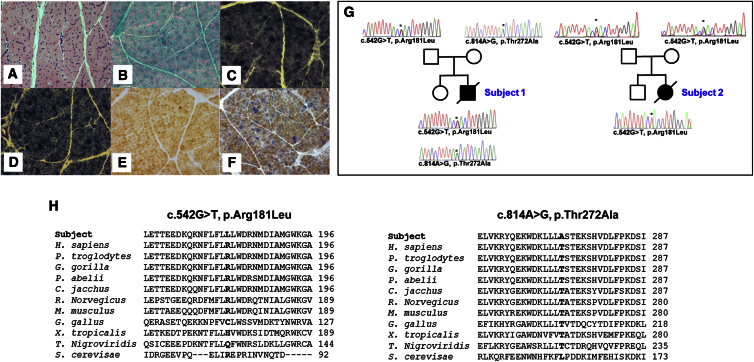

Informed consent for diagnostic and research studies was obtained for both subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocols and approved by local Institutional Review Boards in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, and Paris, France. Biochemical analysis of skeletal muscle samples identified clear mitochondrial enzyme defects involving both complex I and IV in both subjects, whereas complex III activity was normal in subject 1 but decreased in subject 2; both cases showed sparing of complex II activity (Table 1). Histopathological analysis of muscle from subject 1 revealed evidence of subsarcolemmal mitochondrial accumulation (ragged red fibers) and a mosaic pattern of cytochrome c oxidase (COX) deficiency (Figures 1A–1F).

Table 1.

Biochemical and Clinical Findings in Individuals with TRMT10C Variants

| ID | Sex |

TRMT10C Variants |

OXPHOS Activities in Skeletal Muscle |

Clinical Features |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA (NM_017819.3); Protein (NP_060289.2) | RCC | % Mean Enzyme Activity | Absolute Values | Control Mean (Reference Range) | Muscle Biopsy Findings | Age at Onset | Clinical Course | Other Clinical Features and Relevant Family History | ||

| Subject 1a | male | c.[542G>T];[814A>G]; p.[Arg181Leu];[Thr272Ala] | I II III IV |

48% (↓) 103% 98% 23% (↓) |

0.050 0.150 0.543 0.259 |

0.104 ± 0.036 (n = 25) 0.145 ± 0.047 (n = 25) 0.554 ± 0.345 (n = 25) 1.124 ± 0.511 (n = 25) |

COX-deficient, ragged-red fibers | birth | died at 5.5 months | myopathy, hypotonia, sensorineural deafness, liver involvement; elevated serum and CSF lactate levels |

| Subject 2b | female | c.[542G>T];[542G>T]; p.[Arg181Leu];[Arg181Leu] | I II III IV CS |

64% (↓) 293% 8% (↓) 6% (↓) 332% |

11 88 24 9 319 |

17 ± 4 (n = 50) 30 ± 7 (n = 50) 303 ± 57 (n = 50) 144 ± 34 (n = 50) 96 ± 18 (n = 50) |

ND | birth | died at 5 months | hypotonia, deafness; elevated serum, urine, and CSF lactate levels |

Respiratory chain complex (RCC) activities are expressed as nmols NADH oxidised.min−1.unit citrate synthase−1for complex I, nmols DCPIP reduced.min−1.unit citrate synthase−1 for complex II and K.s−1.unit citrate synthase−1 × 103 for complexes III and IV

Respiratory chain complex (RCC) activities are expressed as nmol/min/mg protein

Figure 1.

Autosomal-Recessive TRMT10C Variants Affect Evolutionarily Conserved Amino Acids and Are Associated with Mitochondrial Dysfunction

(A–G) Histopathological analysis of skeletal muscle sections from subject 1 showing (A) hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, (B) modified Gomori trichrome staining, (C) succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) histochemistry, (D) NADH-tetrazolium reductase histochemistry, (E) cytochrome c oxidase (COX) histochemistry, and (F) sequential COX-SDH histochemistry, which clearly illustrates a mosaic pattern of COX deficiency (G). Pedigree and sequencing chromatograms for the families of subject 1 (left) and 2 (right) showing segregation of biallelic TRMT10C variants.

(H) Sequence alignment depicting the evolutionary conservation of the affected amino acids (bold).

Analysis of muscle DNA from both subjects excluded mtDNA abnormalities (mtDNA rearrangements and point mutations) and mtDNA copy number was shown to be normal in each case (data not shown). Whole-exome sequencing via previously described methodologies and bioinformatic filtering pipelines2, 15 identified biallelic variants in TRMT10C (MIM: 615423; GenBank: NM_017819.3; also known as MRPP1 and RG9MTD1). Compound heterozygous c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) (ClinVar: SCV000264779.0) and c.814A>G (p.Thr272Ala) (ClinVar: SCV000264780.0) variants were identified in subject 1, whereas subject 2 was homozygous for the c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) variant, also identified in subject 1. Sanger sequencing was undertaken to validate the variants and confirm that these segregated with disease in each family (Figure 1G). Both identified TRMT10C variants are predicted to result in amino acid substitutions affecting evolutionarily conserved residues (Figure 1H) and are rare: the c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) variant is present on the ExAC database (10/120,324 alleles) and ESP6500 (1/11,824 alleles) whereas the c.814A>G (p.Thr272Ala) TRMT10C variant is absent on ExAC, ESP6500, and COSMIC. In silico predictions via SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and aGVGD suggest that the biophysico impact of the p.Arg181Leu substitution are relatively benign but that the proximity of the Arg181 residue to the TRM10-type domain (predicted from Met191) could hint at a crucial structural role that only an arginine residue can perform. In silico modeling of the TRMT10C variants via RaptorX and Phyre2 produced disparate predictions of MRPP1 protein structure and thus could not be used to indicate any potential misfolding as a consequence of the variants.

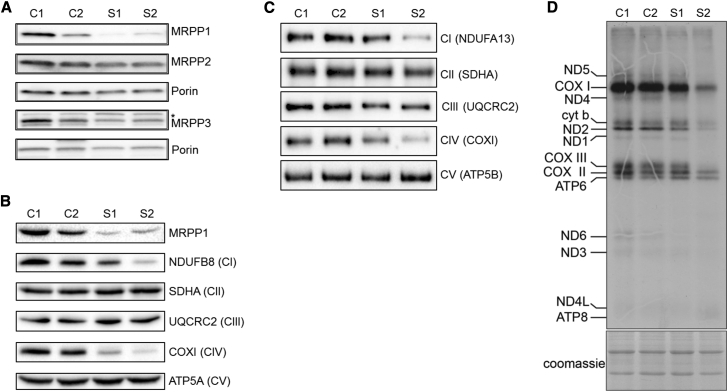

To investigate the functional effects of the identified TRMT10C variants, Western blot and mitochondrial protein synthesis assays were performed in fibroblast cell lines derived from both affected individuals and age-matched control subjects. These data showed that the steady-state levels of MRPP1 were markedly decreased in the subject cell lines, suggesting that the variants affect the stability of the protein (Figure 2A). On the other hand, levels of MRPP2 and MRPP3, the other two subunits of RNase P, were unchanged in fibroblasts from affected individuals (Figure 2A). The loss of MRPP1 protein level correlates with decreased steady-state levels of subunits of complex I (NDUFB8) and complex IV (COXI) (Figure 2B), in agreement with the multiple respiratory chain defects observed in muscle. We used blue native PAGE to determine the effects on the assembly and stability of the respiratory chain complexes16 and show a marked decrease of fully assembled complex I and complex IV, with a slight decrease in complex III levels (Figure 2C). The low steady-state levels of mtDNA-encoded proteins was due to impaired mitochondrial protein synthesis in subject fibroblasts as demonstrated by reduced incorporation of 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Mutant MRPP1 Protein Is Unstable and Leads to Impaired Mitochondrial Protein Synthesis Causing Multiple Respiratory Chain Defects

(A) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial extracts from control and affected individuals using commercial MRPP1-, MRPP2-, and MRPP3-specific antisera. Porin (VDAC1) was used as a loading control. Asterisk (∗) indicates cross-reacting band.

(B) Western blot analyses of protein extracts from affected fibroblasts showing decreased levels of MRPP1 and subunits of mitochondrial respiratory complexes I (NDUFB8) and IV (COXI and COXII).

(C) Blue-native PAGE analysis of OXPHOS complex assembly using mitochondrial extracts in 1% DDM from control and subject fibroblasts (as described previously16) demonstrated decreased assembly of OXPHOS complexes I and IV and to a lesser extent complex III in subject fibroblasts.

(A–C) Samples (25 μg protein) were fractionated through 4%–16% native gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) transferred onto PVDF membranes and subjected to western immunoblotting. Subunits from individual OXPHOS complexes were detected using specific antibodies: complex I (NDUFA13), complex II (SDHA), complex III (UQCRC2), complex IV (COXI), and complex V (ATP5B).

(D) In vitro labeling of de novo synthesized mitochondrial translation products with EasyTag EXPRESS35S Protein Labeling Mix (Perkin Elmer) followed by fractionation through a 17% SDS-Polyacrylamide gel and autoradiography (as described previously32). Coomassie brilliant blue staining of the gels was used to demonstrate equal loading.

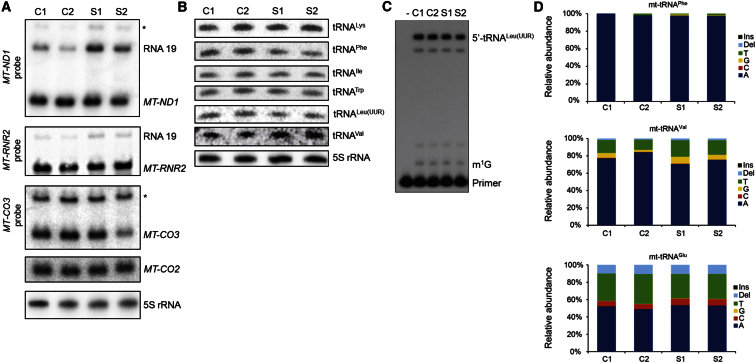

Because MRPP1 is known to be an essential subunit of the mitochondrial RNase P,6 which is responsible for 5′ cleavage of mt-tRNAs from the polycistronic mitochondrial transcripts, we investigated whether fibroblasts from affected individuals showed evidence of impaired mitochondrial RNA processing. Northern blot analyses showed an increase in RNA precursor RNA19 when detected with either an MT-ND1 or MT-RNR2 probe (Figure 3A). However, the steady-state levels of the mature mRNAs were not significantly affected. No increase in precursors of MT-CO2 or MT-CO3 were observed, although the steady-state levels of mature MT-CO3 appeared to be slightly decreased in subject 2 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

TRMT10C Variants Lead to Altered RNA Processing but Do Not Affect Methylation at Position 9

(A) Northern blot analyses of mt-mRNA steady-state levels using radiolabelled probes specific for MT-ND1, MT-RNR2 (16 s rRNA), MT-CO2, and MT-CO3. Asterisk (∗) denotes putative mtRNA precursors.

(B) High-resolution Northern blot analyses of mt-tRNAs using radiolabelled oligonucleotide probes against mt-tRNAs with 5S rRNA as a loading control (performed as described previously33).

(C) Primer extension analysis of m1G9 in tRNALeu(UUR) using a radiolabeled primer (5′- TTATGCGATTACCGGGCTCTGC-3′) annealing 1 base downstream of the modified residue. Primer and 3 μg RNA were denatured at 95°C for 5 min and cooled on ice. Primer extensions were carried out using AMV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 45°C for 1 hr and stopped by heating at 85°C for 15 min. After ethanol precipitation, the samples were analyzed by fractionation through a 12% polyacrylamide-urea gel and autoradiography. Extension of the primer is partially inhibited by the presence of methylated G9 in mt-tRNALeu(UUR) leading to the accumulation of a single-base extension product (labeled m1G) that is detectable in both control and in case subject RNA at similar levels.

(D) Sequencing error rates at position 9 in mt-tRNAPhe, mt-tRNAVal, and mt-tRNAGlu determined by RNA-seq analysis of mitochondrial RNAs extracted from control and subjects’ fibroblasts. The relative abundance of individual nucleotides and indels generated by the presence of m1R9 was analyzed as described previously.7

Processing of mt-tRNAs at the 3′ end is carried out by ELAC2.7, 8, 10 Because both subjects had functional copies of ELAC2, it would be expected that the mt-tRNAs would be processed at the 3′ end, but not at the 5′ end, resulting in mt-mRNAs with an uncleaved mt-tRNA at the 3′ end. The resolution of the Northern blots for mt-mRNAs was not sufficient to distinguish between mature mRNA and these pre-processed transcripts, thus, high-resolution Northern blot experiments were performed to assess the levels of mature mt-tRNAs (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, the steady-state levels of mt-tRNAs were not significantly altered in the affected individuals relative to controls, suggesting that the severe mitochondrial translation defect was not due to absence of cleaved mt-tRNAs. However, mt-tRNAPhe and mt-tRNALeu(UUR) appeared to have slightly lower steady-state levels in subject fibroblasts relative to controls.

To further investigate precursor processing, we carried out RNA-seq analysis of mitochondrial RNA isolated from control and affected individuals. Differential analyses of mt-mRNA and mt-tRNA gene expression in TruSeq library datasets and small RNA library datasets, respectively, revealed no significant differences in mitochondrially encoded mt-mRNA, mt-rRNA, and mt-tRNA levels between the samples (not shown). However, when we investigated the changes in the abundance of reads across the entire mitochondrial transcriptome, we found an increase in the regions that span gene boundaries, where RNA processing is required to release individual mitochondrial RNAs from the precursor transcripts (Figure S1). Together, these data confirm an impairment of mt-tRNA processing efficiency without severe effects on mature mt-mRNA or mt-tRNA steady-state levels. It is possible that the cleavage of mt-tRNAs by mt-RNase P is less efficient in cells harboring TRMT10C/MRPP1 variants, but that the mt-tRNAs that are cleaved are very stable, thus retaining steady-state mt-tRNA levels to approximately wild-type levels.

All tRNAs undergo post-translational modification at numerous sites to promote their correct function.11, 17 The mt-tRNAs are not exceptions and cleavage from the polycistronic mt-RNA transcripts is just one step in their maturation. In addition to their role in RNase P activity, MRPP1 and MRPP2 act as an m1R9 methyltransferase.14 Methylation of either G or A at position 9 is vital for the correct structure and function of mt-tRNAs.12, 13, 18 Thus, we sought to investigate the impact of the TRMT10C variants on m1R9 methyltransferase activity in subject fibroblasts. To this aim, we utilized two experimental approaches: (1) primer extension analysis of individual mt-tRNAs during which the reverse transcriptase-mediated extension of a radiolabelled primer is inhibited by the presence of m1R9 modification19 and (2) RNA-seq analysis, because m1 methylation at position 9 has been shown to increase the sequencing error rate at this position.7 Primer extension analysis of mt-tRNALeu(UUR) revealed no difference between control subjects and affected individuals (Figure 3C). Similarly, there was no change in the sequencing error rates between subject and control samples (Figure 3D). These data indicate that the m1R9 methyltransferase activity is not affected by the p.Arg181Leu and p.Thr272Ala MRPP1 variants.

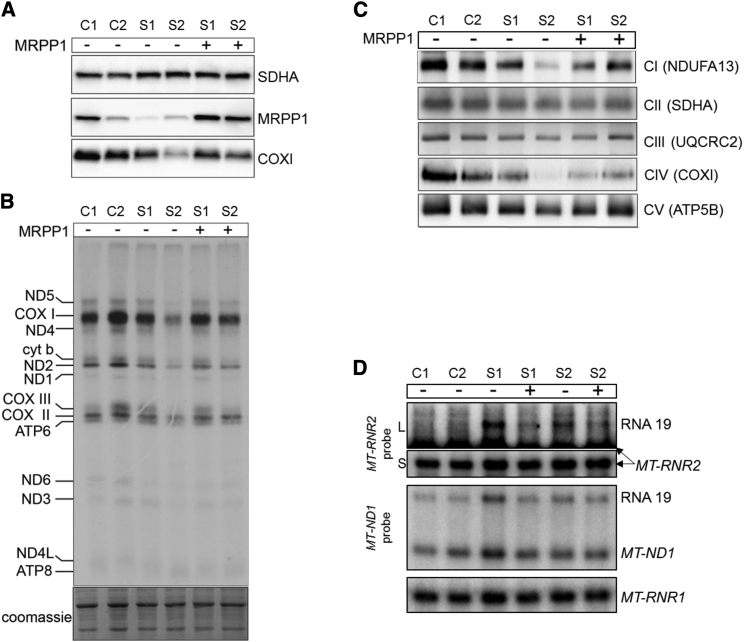

We have demonstrated that tRNA 5′ processing is affected in fibroblasts from affected individuals with mutant MRPP1, which is consistent with current knowledge of the function of MRPP1 as a component of mt-RNase P. However, to definitively prove that the mitochondrial OXPHOS defect is a consequence of the TRMT10C variants, lentiviral rescue experiments were performed to complement the respiratory phenotype expressed in cultured cells. Fibroblast cell lines from affected individuals were transfected with a lentiviral vector carrying a copy of the wild-type TRMT10C gene encoding MRPP1. The complemented cell lines displayed increased expression of MRPP1 protein level (Figure 4A), leading to a restoration of mitochondrial translation (Figures 4A and 4B) and normal levels of fully assembled respiratory chain complexes (Figure 4C). Furthermore, the level of mt-RNA precursors, elevated in subject fibroblasts, normalized after lentiviral transduction with wild-type TRMT10C (Figure 4D). These data verify the pathogenicity of the c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) and c.814A>G (p.Thr272Ala) TRMT10C variants, establishing these variants as causative of mitochondrial disease associated with multiple respiratory chain abnormalities.

Figure 4.

Lentiviral Expression of Wild-Type TRMT10C Restores RNA Processing, Expression of mtDNA-Encoded Proteins, and OXPHOS Assembly in Subjects’ Fibroblasts

(A) Western blot analysis of fibroblast extracts transduced with lentiviral particles expressing wild-type TRMT10C. MRPP1, COXI, and SDHA were detected with specific antisera. SDHA was used as a loading control.

(B) In vitro mitochondrial translation in subjects’ fibroblasts transduced with control lentiviral particles or particles expressing wild-type TRMT10C. Analyses were performed as in Figure 2C.

(C) Blue-native PAGE analysis of OXPHOS assembly in rescued subjects’ fibroblasts performed as in Figure 2B, showing restoration of complex assembly.

(D) Northern blot analysis of RNA processing in complemented fibroblasts analyzed as in Figure 3A. For MT-RNR2 (16S mt-rRNA), short (S) exposure was used with a long (L) exposure shown to highlight the weaker band corresponding to RNA19. Representative images from three independent lentiviral rescue experiments are shown for each panel of this figure.

Prenatal diagnosis has subsequently been offered to both families in subsequent pregnancies after the identification and validation of pathogenic TRMT10C variants. In the first family harboring compound heterozygous changes, both TRMT10C variants were identified in a later pregnancy after chorionic villus biopsy, leading to termination. In family 2 (homozygous variant), the fetus was heterozygous for the c.542G>T (p.Arg181Leu) TRMT10C variant and mitochondrial respiratory chain activities were normal in the chorionic villus biopsy sample (data not shown), supportive of an unaffected clinical status.

Of interest, we noted that both affected individuals showed decreased MRPP1 steady-state protein levels in fibroblasts, although the levels in subject 1 (compound heterozygote variants) had lower levels than subject 2 (homozygous variant), suggesting that the p.Thr272Ala mutant MRPP1 protein is less stable than the p.Arg181Leu mutant. However, despite having higher residual levels of MRPP1, cells from subject 2 exhibited a more severe impairment of mitochondrial protein synthesis resulting in lower steady-state levels of respiratory chain complexes I and IV, implying the p.Arg181Leu mutant protein is more stable but less active than the p.Thr272Ala mutant protein.

The impairment of mt-RNA processing observed in fibroblasts from the affected individuals was not as severe as we anticipated, with steady-state levels of mature mt-mRNAs and mt-tRNAs largely unaffected. However, these data fit well with reports of mutations in other proteins involved with RNA processing, given that mutations in ELAC220 and HSD17B1021 have both been shown to lead to an accumulation of mt-RNA precursors without effects on the levels of mature mt-mRNA and mt-tRNAs. Furthermore, it has been shown that loss of MRPP2 levels leads to a reduction in steady-state levels of MRPP1.21, 22 Given that the increase in RNA precursors (RNA19) we report was similar to those seen in subjects with deleterious HSD17B10 (MRPP2) variants (MIM: 300438),21 it is possible that decreased MRPP1 protein levels are particularly important for RNA processing because MRPP2 levels were not shown to be diminished in either of the cases documented here (Figure 2B). Conversely, we did not find any evidence of altered m1R9 methyltransferase activity in fibroblasts from either affected individual, implying that the observed defect in mitochondrial protein synthesis is due to a decrease in the efficiency of mt-RNA processing rather than any effects on mt-tRNA modification. The m1R9 methyltransferase activity is carried out by a stable protein complex of MRPP1 and MRPP2,14 whereas the RNA processing requires MRPP3,6 which contains the active site of the nuclease activity of RNase P.23, 24 Therefore, one attractive hypothesis is to suggest that the p.Arg181Leu and p.Thr272Ala TRM10C variants disrupt the interaction between MRPP1 and MRPP3 without affecting the complex with MRPP2, although this requires future investigation.

Knowledge of defects in mt-tRNA processing or modification leading to disease has expanded in recent years including the aforementioned variants in HSD17B10 (MRPP2)21 and ELAC2,20 as well as mutations in numerous mt-tRNA modifier proteins including PUS125 (MIM: 608109), TRIT1,26 TRMU27 (MIM: 610230), TRNT128 (MIM: 612907), TRMT519 (MIM: 611023), MTO129, 30 (MIM: 614667), and GTPBP331 (MIM: 608536). Mutations in TRMT10C (MRPP1) can now be added to this growing list as we show that the introduction of wild-type MRPP1 into fibroblasts from affected individuals is sufficient to rescue their mitochondrial defects, confirming these TRMT10C variants as pathogenic in mitochondrial disease associated with impaired mitochondrial translation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (096919/Z/11/Z) (R.W.T., R.M., and P.F.C.); MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases (G0601943) (R.W.T., R.M., and P.F.C.); UK NHS Highly Specialised “Rare Mitochondrial Disorders of Adults and Children” Service (R.M. and R.W.T.), and The Lily Foundation (R.W.T., R.M., and K.T.). C.L.A. is supported by a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) doctoral fellowship (NIHR-HCS-D12-03-04). P.F.C. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow in Clinical Science (101876/Z/13/Z) and a UK NIHR Senior Investigator who receives additional support from the Medical Research Council Mitochondrial Biology Unit (MC_UP_1501/2), EU FP7 TIRCON, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and the University of Cambridge. M.D.M. is supported by a fellowship from AFM (16615). A.F. is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Research Fellow (APP 1058442) and is supported by grants from the NHMRC (APP1078273 and APP1041582) an Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship for experienced researchers. A.R. is supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies and E-Rare project GENOMIT (01GM1207). RNA library construction and sequencing were performed at the Cologne Center for Genomics, Cologne, Germany.

Published: April 28, 2016; corrected online: June 21, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include one figure and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.010.

Contributor Information

Agnès Rötig, Email: agnes.rotig@inserm.fr.

Robert W. Taylor, Email: robert.taylor@ncl.ac.uk.

Accession Numbers

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in GEO at GSE79120 and in ClinVar at SCV000264779.0 and SCV000264780.0 for c.542G>T and c.814A>G, respectively.

Web Resources

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

Phyre2, http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

RaptorX, http://raptorx.uchicago.edu

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Anderson S., Bankier A.T., Barrell B.G., de Bruijn M.H., Coulson A.R., Drouin J., Eperon I.C., Nierlich D.P., Roe B.A., Sanger F. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor R.W., Pyle A., Griffin H., Blakely E.L., Duff J., He L., Smertenko T., Alston C.L., Neeve V.C., Best A. Use of whole-exome sequencing to determine the genetic basis of multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain complex deficiencies. JAMA. 2014;312:68–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell C.A., Nicholls T.J., Minczuk M. Nuclear-encoded factors involved in post-transcriptional processing and modification of mitochondrial tRNAs in human disease. Front. Genet. 2015;6:79. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lightowlers R.N., Taylor R.W., Turnbull D.M. Mutations causing mitochondrial disease: What is new and what challenges remain? Science. 2015;349:1494–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ojala D., Montoya J., Attardi G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature. 1981;290:470–474. doi: 10.1038/290470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holzmann J., Frank P., Löffler E., Bennett K.L., Gerner C., Rossmanith W. RNase P without RNA: identification and functional reconstitution of the human mitochondrial tRNA processing enzyme. Cell. 2008;135:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez M.I.G.L., Mercer T.R., Davies S.M.K., Shearwood A.-M.J., Nygård K.K.A., Richman T.R., Mattick J.S., Rackham O., Filipovska A. RNA processing in human mitochondria. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2904–2916. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.17.17060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brzezniak L.K., Bijata M., Szczesny R.J., Stepien P.P. Involvement of human ELAC2 gene product in 3′ end processing of mitochondrial tRNAs. RNA Biol. 2011;8:616–626. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.15393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takaku H., Minagawa A., Takagi M., Nashimoto M. A candidate prostate cancer susceptibility gene encodes tRNA 3′ processing endoribonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2272–2278. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossmanith W. Localization of human RNase Z isoforms: dual nuclear/mitochondrial targeting of the ELAC2 gene product by alternative translation initiation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T., Suzuki T. A complete landscape of post-transcriptional modifications in mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7346–7357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helm M., Brulé H., Degoul F., Cepanec C., Leroux J.P., Giegé R., Florentz C. The presence of modified nucleotides is required for cloverleaf folding of a human mitochondrial tRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1636–1643. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voigts-Hoffmann F., Hengesbach M., Kobitski A.Y., van Aerschot A., Herdewijn P., Nienhaus G.U., Helm M. A methyl group controls conformational equilibrium in human mitochondrial tRNALys. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:13382–13383. doi: 10.1021/ja075520+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vilardo E., Nachbagauer C., Buzet A., Taschner A., Holzmann J., Rossmanith W. A subcomplex of human mitochondrial RNase P is a bifunctional methyltransferase--extensive moonlighting in mitochondrial tRNA biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11583–11593. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vedrenne V., Gowher A., De Lonlay P., Nitschke P., Serre V., Boddaert N., Altuzarra C., Mager-Heckel A.-M., Chretien F., Entelis N. Mutation in PNPT1, which encodes a polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase, impairs RNA import into mitochondria and causes respiratory-chain deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metodiev M.D., Spåhr H., Loguercio Polosa P., Meharg C., Becker C., Altmueller J., Habermann B., Larsson N.-G., Ruzzenente B. NSUN4 is a dual function mitochondrial protein required for both methylation of 12S rRNA and coordination of mitoribosomal assembly. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki T., Nagao A., Suzuki T. Human mitochondrial tRNAs: biogenesis, function, structural aspects, and diseases. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:299–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurai M., Ohtsuki T., Watanabe K. Modification at position 9 with 1-methyladenosine is crucial for structure and function of nematode mitochondrial tRNAs lacking the entire T-arm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1653–1661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell C.A., Kopajtich R., D’Souza A.R., Rorbach J., Kremer L.S., Husain R.A., Dallabona C., Donnini C., Alston C.L., Griffin H. TRMT5 mutations cause a defect in post-transcriptional modification of mitochondrial tRNA associated with multiple respiratory-chain deficiencies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haack T.B., Kopajtich R., Freisinger P., Wieland T., Rorbach J., Nicholls T.J., Baruffini E., Walther A., Danhauser K., Zimmermann F.A. ELAC2 mutations cause a mitochondrial RNA processing defect associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deutschmann A.J., Amberger A., Zavadil C., Steinbeisser H., Mayr J.A., Feichtinger R.G., Oerum S., Yue W.W., Zschocke J. Mutation or knock-down of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 cause loss of MRPP1 and impaired processing of mitochondrial heavy strand transcripts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:3618–3628. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez M.I.G.L., Shearwood A.-M.J., Chia T., Davies S.M.K., Rackham O., Filipovska A. Estrogen-mediated regulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015;29:14–27. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinhard L., Sridhara S., Hällberg B.M. Structure of the nuclease subunit of human mitochondrial RNase P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:5664–5672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li F., Liu X., Zhou W., Yang X., Shen Y. Auto-inhibitory mechanism of the human mitochondrial RNase P protein complex. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9878. doi: 10.1038/srep09878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bykhovskaya Y., Casas K., Mengesha E., Inbal A., Fischel-Ghodsian N. Missense mutation in pseudouridine synthase 1 (PUS1) causes mitochondrial myopathy and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:1303–1308. doi: 10.1086/421530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarham J.W., Lamichhane T.N., Pyle A., Mattijssen S., Baruffini E., Bruni F., Donnini C., Vassilev A., He L., Blakely E.L. Defective i6A37 modification of mitochondrial and cytosolic tRNAs results from pathogenic mutations in TRIT1 and its substrate tRNA. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeharia A., Shaag A., Pappo O., Mager-Heckel A.-M., Saada A., Beinat M., Karicheva O., Mandel H., Ofek N., Segel R. Acute infantile liver failure due to mutations in the TRMU gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakraborty P.K., Schmitz-Abe K., Kennedy E.K., Mamady H., Naas T., Durie D., Campagna D.R., Lau A., Sendamarai A.K., Wiseman D.H. Mutations in TRNT1 cause congenital sideroblastic anemia with immunodeficiency, fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD) Blood. 2014;124:2867–2871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-591370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baruffini E., Dallabona C., Invernizzi F., Yarham J.W., Melchionda L., Blakely E.L., Lamantea E., Donnini C., Santra S., Vijayaraghavan S. MTO1 mutations are associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and lactic acidosis and cause respiratory chain deficiency in humans and yeast. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:1501–1509. doi: 10.1002/humu.22393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghezzi D., Baruffini E., Haack T.B., Invernizzi F., Melchionda L., Dallabona C., Strom T.M., Parini R., Burlina A.B., Meitinger T. Mutations of the mitochondrial-tRNA modifier MTO1 cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and lactic acidosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:1079–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopajtich R., Nicholls T.J., Rorbach J., Metodiev M.D., Freisinger P., Mandel H., Vanlander A., Ghezzi D., Carrozzo R., Taylor R.W. Mutations in GTPBP3 cause a mitochondrial translation defect associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and encephalopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;95:708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leary S.C., Sasarman F. Oxidative phosphorylation: synthesis of mitochondrially encoded proteins and assembly of individual structural subunits into functional holoenzyme complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;554:143–162. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-521-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almalki A., Alston C.L., Parker A., Simonic I., Mehta S.G., He L., Reza M., Oliveira J.M.A., Lightowlers R.N., McFarland R. Mutation of the human mitochondrial phenylalanine-tRNA synthetase causes infantile-onset epilepsy and cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.