Abstract

Adenosine is a naturally occurring purine nucleoside in every cell. Many critical treatments such as modulating irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias), regulation of central nervous system (CNS) activity, and inhibiting seizural episodes can be carried out using adenosine. Despite the significant potential therapeutic impact of adenosine and its derivatives, the severe side effects caused by their systemic administration have significantly limited their clinical use. In addition, due to adenosine’s extremely short half-life in human blood (less than 10 s), there is an unmet need for sustained delivery systems to enhance efficacy and reduce side effects. In this paper, various adenosine delivery techniques, including encapsulation into biodegradable polymers, cell-based delivery, implantable biomaterials, and mechanical-based delivery systems, are critically reviewed and the existing challenges are highlighted.

1. Introduction

The adenosine molecule (C10H13N5O4) is a nucleoside involving a molecule of adenine bound to ribose (Hasko and Cronstein, 2004, Sawynok and Liu, 2003). It is produced by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) metabolism and also takes part in ATP synthesis in mitochondria. Adenosine is combined with phosphate to form adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and ATP (Faulds et al., 1991, Agteresch et al., 1999). ATP consists of three phosphate groups bound to adenosine, and is the high-energy molecule that transports chemical energy for metabolism (Mendonça et al., 2000, Wojcik and Neff, 1982, Agteresch et al., 1999). Moreover, ATP is believed to be involved in the regulation of central nervous system (Bjorklund) and cardiac function. It affects vasodilatation, muscle contraction, bone metabolism, inflammation, and liver glycogen metabolism.

Adenosine 5'-diphosphate (ADP) is formed by the hydrolysis of ATP and is converted back to ATP by the glycolysis, metabolic processes oxidative phosphorylation, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. ADP involves in platelet activation process. AMP takes part in energy metabolism and nucleotide synthesis and is used as a monomer in RNA (Agteresch et al., 1999, Hoebertz et al., 2003, Burnstock and Knight, 2004, Paidas et al., 1989).

Adenosine also functions as a ubiquitous endogenous cell signaling (Wang et al., 2000) and a modulator agent. Adenosine’s important role in regulating many physiologic cell-signaling pathways (particularly in the brain and heart) is well recognized (Fredholm, 2014, Mendonça et al., 2000, Fredholm et al., 2011). Adenosine is involved in almost every aspect of cell function by activating four G-proteins or alternately P1 receptors (ARS: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) and the eight subtypes of P2YRS receptors (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11RS, P2Y12, P2Y13, P2Y14RS) located on the cell surface. Many studies are developing ligands for these receptors for pharmaceuticals (Fredholm, 2014, Mendonça et al., 2000, Fredholm et al., 2011). For example, ligand of AR antagonists are capable to treat sleep apnea, cancer pain, asthma (Ecke et al., 2008, Guo et al., 2002). A1 agonists have been shown to be effective for Glaucoma, atrial fibrillation, and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Tosh et al., 2011, Fredholm et al., 2011). A2A agonists can inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and have anti-inflammatory and anti-ischemic effects (Wang et al., 2010). A2A agonists have been developed for the treatment of sickle cell disease, chronic and neuropathic pain, wound healing and other disorders of the central nervous system including addiction. A2A antagonists have been studied for Parkinson’s disease, and its PET imaging (Ballesteros et al., 1995). A3 agonists may be used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, dry eye, glaucoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1). P2Y12 agonist and P2Y12 antagonist can treat dry eye disease, and acute coronary syndrome respectively (Mao et al., 2010).

Adenosine white crystalline powder is water-soluble and insoluble in alcohols, with pKa values of 3.5 and 12.5, which is stable in solution with pH between 6.8 and 7.4. Lowering the pH and increasing the temperature enhance the adenosine solubility (Gabrielian, 1977, Dawson, 1986).

More than 80 years ago, Drury and Szent-Györgyi conducted some of the early research on adenosine identifying the link between adenosine and cardiac function and energy metabolism (Drury and Szent-Györgyi, 1929). It was shown that under conditions of energy deficiency, the release of adenosine results in an increase in blood flow and respiration, and a reduction in cellular work (Drury and Szent-Györgyi, 1929, Berne, 1980). Since then, the effect of adenosine on these functions has been elaborated considerably (Pak et al., 2015, FDA, 2013, Takahama et al., 2009, Dunwiddie, 1999).

Two brands of adenosine (Adenocard® and Adenoscan®) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are currently available on the market (Paidas et al., 1989). Adenocard®, Adenoscan® formulations contains 3 mg adenosine, and 9 mg sodium chloride per mL of water, and have been indicated for treating “Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome”. They have been approved for use during cardiac stress tests in patients who cannot exercise adequately. The algorithm for Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) protocol suggests administration of the adenosine through the atrioventricular (AV) node as a primary drug for restoring sinus rhythm for treating supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and regular monomorphic wide-complex tachycardia.

Additionally, research suggests that administration of adenosine derivative AMP by intramuscular injection may be used for treating neuropathy (Melemedjian et al., 2011), multiple sclerosis (MS) (Tsutsui et al., 2004), bursitis (Pelner and Waldman, 1952), pain and tendonitis (Rottino, 1951, Zylka, 2011), varicose veins (Schmidt et al., 1989, Raffetto et. al., 2012), pruritus (Lynch et al., 2003), fever blisters (Sklar and Buimoviciklein, 1979), herpes zoster (Sklar et al., 1985, Ma and He 2014), genital herpes (Handler et al., 1983, Ma and He 2014), and poor blood circulation (Hofmann et al., 1975). Oral administration of AMP can be used for herpes zoster infection (Sklar et al., 1985), and treating a blood disorder called porphyria cutanea tarda (Gajdos, 1974). ATP can be administrated intravenously to treat pulmonary hypertension (Paidas et al., 1989, Ghofrani HA et al., 2002), blood pressure during anesthesia and surgery (Sollevi et al., 1984), lung cancer (Agteresch et al., 2000), multiple organ failure (Arthur, 2000), weight loss associated with cancer (Khal et al., 2005), acute kidney failure (Bonventre and Zuk, 2004), cystic fibrosis (Hyde et al., 1990), ischemia (Feigl, 2004), and cardiac stress tests (Faulds et al., 1991). ATP can also be used sublingually for quick absorption to increase physical energy (Padykula and Herman, 1955). ATP deficiency has been reported to be one major cause of non-healing chronic diabetic wounds which is due to low energy availability created by wound hypoxia, resulting in blood and oxygen deficiency in wound cells (Wang et al., 2009a). It has also been reported that ATP level is an indication for the extent of hepatic disease; therefore, delivery of ATP to the targeted hepatopathy tissue might be used to diagnose early hepatic disease (Lehr et al., 1992). ADP has been indicated as an initial treatment for the termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PVST) associated with accessory bypass tracts. It also applied in patients who are unable to exercise adequately as an adjunct to thallous chloride TI 201 myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. ADP is one of the favorite drugs for terminating stable, narrow-complex SVT, and diagnosis of undefined, stable, narrow-complex SVT by being used as an adjunct to vagal maneuvers (Belardinelli, 2004).

Under conditions of cellular distress such as seizures, the adenosine levels in cells and tissue fluids rapidly rise, and this is responsible for the termination of the seizure (Boison, 2006, Fredholm, 2007). Epilepsy is a chronic disorder of the brain that is characterized by spontaneous recurrent seizures and affects approximately 70 million people worldwide (Boison, 2007a, McNamara, 1999, Boison and Stewart, 2009). Despite the advent of new anti-epileptic drugs, about 35% patients have experienced continuous seizures with complex partial epilepsy, which is believed to be due to intolerable systemic side effects of these drugs (McNamara, 1999, Vajda, 2007). Adenosine deaminase (ADA) and especially adenosine kinase (ADK), which largely exists in astrocytes in the brain catabolize the adenosine, and are responsible for maintaining the adenosine level (Fredholm, 2007). It has been shown that adenosine has antiseizure activities in several models of epilepsy. Nevertheless, due to cardiovascular side effects, and liver toxicity of ADK disruption the systemic administration of adenosine is not practical (Olsson and Pearson, 1990, Boison et al., 2002b, Fredholm et al., 2005). Another interesting application for adenosine is antiplatelet therapy, which has not yet been clinically used because of adenosine short half-life (Johnston-Cox and Ravid, 2011).

Despite the abundance of evidence suggesting the significant therapeutic impact of adenosine/adenosine derivatives, systemic administration of adenosine may induce severe side effects, such as suppression of cardiac function, decreased blood pressure and body temperature, hypotension, and sedative side effects (Takahama et al., 2009, Dunwiddie, 1999, FDA, 2013). In a clinical trial reported by the FDA, among 1421 patients who received intravenous adenosine injection, 44%, 40%, 28%, 18% and 15% experienced flushing, chest discomfort, dyspnea (urge to breath deeply), headache, and throat/neck or jaw discomfort, respectively. Adenosine has low blood-brain barrier permeability and an extremely short half-life (less than 10 s). Adenosine is cleared rapidly from the circulation via cellular uptake primarily by erythrocytes and vascular endothelial cells. In this process adenosine is quickly deaminated by adenosine deaminase to inosine, and subsequently is broken down to uric acid, xanthine, and hypoxanthine, which eventually is excreted by the kidneys (Forman et al., 2006, Pagonopoulou et al., 2006). Therefore, sustained adenosine delivery systems are required to enhance the efficacy and consequently reduce the side effects by slow release at a concentration within the therapeutic window. Normal cells produce about 300 nM extracellular adenosine concentrations; however, in some cases such as inflammation the concentrations may reach to 600–1200 nM. The adenosine concentration needed to activate A1 (0.3–3 nM), A2A (1–20 nM) and A3 (about 1 µM) receptors range between 0.01 µM and 1 µM, and physiological adenosine concentrations are usually lower than 1 µM (Cieslak et al., 2008). The adenosine level to activate A2B receptor generally exceeds 10 µM in response to metabolic stress in pathophysiological conditions (Sachdeva et al., 2013, Hasko et al., 2008).

Drug delivery systems (DDSs) improve the pharmacological and therapeutic properties of drug products. These systems can maintain a steady release of drug level in a therapeutic range and reduce undesirable side effects. They also decrease the amount of drug and number of dosages needed, and provide an efficient administration of pharmaceuticals with short in vivo half-lives (Dash and Cudworth, 1998, Allen and Cullis, 2004, Langer, 1998, Peppas et al., 2006). An ideal DDS is expressed as a system that can pass physiological barriers, shield the drug from the attacks by the immune system, and selectively deliver the drug to the targeted tissue (Ferrari, 2005, Allen and Cullis, 2004, Strebhardt and Ullrich, 2008, Naahidi et al., 2013, Kazemzadeh-Narbat et al., 2010, 2012–2015, , Ma et al., 2012). Such system can adjust both quantity and duration of drug presence in whole body or a specific tissue.

Currently no approved system exists for controllable, sustained, long-term adenosine delivery. This article aims to highlight DDSs that have been proposed for adenosine delivery. This review provides an overview of various biomaterials used for adenosine delivery including polymer/lipid-based, and ceramic-based adenosine delivery. It also explores different techniques such as layer-by-layer assembly, pump-based and cell-based approaches with their practical application for tunable adenosine delivery. Finally, the review outlines future opportunities and directions that the field may expand.

2. Particle-Based Adenosine Carriers

Drug carriers generally deliver the drugs through various mechanisms including diffusion from or through the biomaterials, chemical or enzymatic degradation, solvent activation due to osmosis or swelling, or a combination of these mechanisms (Langer, 1998). Several attempts have been made to deliver adenosine using polymer/lipid materials. These drug carriers can be made from lipids (i.e. liposomes), polymers (i.e. poly(lactic acid), ethylene vinyl acetate, and silk) and hydrogels (i.e. chitosan and polyethylene glycol). In this section, we will critically review the pertinent literature.

2.1 Liposomally Entrapped Adenosine

Liposomes (self-assembled enclosed lipid bilayers) are usually biodegradable, non-toxic vehicles that have been employed for encapsulating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic therapeutics in drug delivery systems (Lian and Ho, 2001). Guo-Xing et al. (Xu et al., 1990) evaluated four methods for encapsulating ATP in liposomes generated from egg lecithin/cholesterol/stearylamine, including thin film-formed vesicles, reverse-phase evaporation vesicles, double emulsification vesicles, and improved emulsification vesicles. The highest ATP entrapment of 38.9% was observed for positively charged liposomes made by the “improved emulsification vesicles” method. They reported that, after 54 days of storage at room temperature, about 11% of ATP was released from liposomes. The positively charged ATP liposomes were then injected intravenously in dogs with experimentally induced myocardial infarction. The results showed the accumulation of ATP in myocardial infarct tissue (Xu et al., 1990).

Based on liposomal entrapment techniques, Gomes et al. (Gomes and Sharma, 2004) reported the encapsulation of Adenosine-3’-5’-Cyclic Monophosphate (cAMP) into vesicles (35–55 nm in diameter) composed of egg-phosphatidylcholine (PC), cholesterol, and sulfatides. They showed that the presence of the protein kinase A in the liposome formulation not only increased the 7% entrapment efficiency of cAMP by 5-fold, but also reduced its leakage by more than 60% in the mouse brain (Gomes and Sharma, 2004).

ATP could be used to aid in treating chronic diabetic wounds if a solution for its short half-life can be devised. It has been shown that the clearance of ATP can be prolonged by encapsulation of magnesium-ATP (Mg-ATP) into small unilamellar lipid vesicles (Wang et al., 2009a, Chien, 2010, Chiang et al., 2007). Chiang et al. (Chiang et al., 2007) developed a technique to create Mg-ATP vesicles by encapsulating Mg-ATP with highly fusogenic lipid (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, (DOPC)) vesicles. They observed that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expressions in the wounds of mice treated with Mg-ATP-vesicles (100 to 200 nm) were significantly higher. This system could accelerate healing by supplying enough blood to deliver oxygen, nutrients, minerals, enzymes, and by circulating hormones into the wound cells (Chiang et al., 2007).

Similarly, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2009a) used Mg-ATP-vesicles (with diameters of 120–160 nm) in ischemic and non-ischemic wounds in diabetic rabbits. They concluded that intracellular ATP delivery enhances the healing process of diabetic skin wounds on ischemic (mean closure time about 15.3 days) and non-ischemic (mean closure time about 13.7 days) rabbit ears (Wang et al., 2009a). Similarly, Chien (Chien, 2010) investigated the intracellular delivery of fusogenic, unilamellar lipid vesicles containing Mg-ATP (with diameters of 100 to 200 nm) into normal or ischemic cells. The in vivo study on the rabbit ischemic ear wound model indicated a significant reduction in healing times in the wounds treated with ATP-vesicles (mean 18.0 ± 1.9 days) in comparison to the saline-treated ones (mean 22.8 ± 4.1 days). Moreover, enhanced re-epithelialization was observed for the wounds treated with ATP-vesicles. According to their in vitro study, when ATP-vesicles were in contact with the endothelial cell membrane, they fused together and delivered their contents into the cytosol (Chien, 2010).

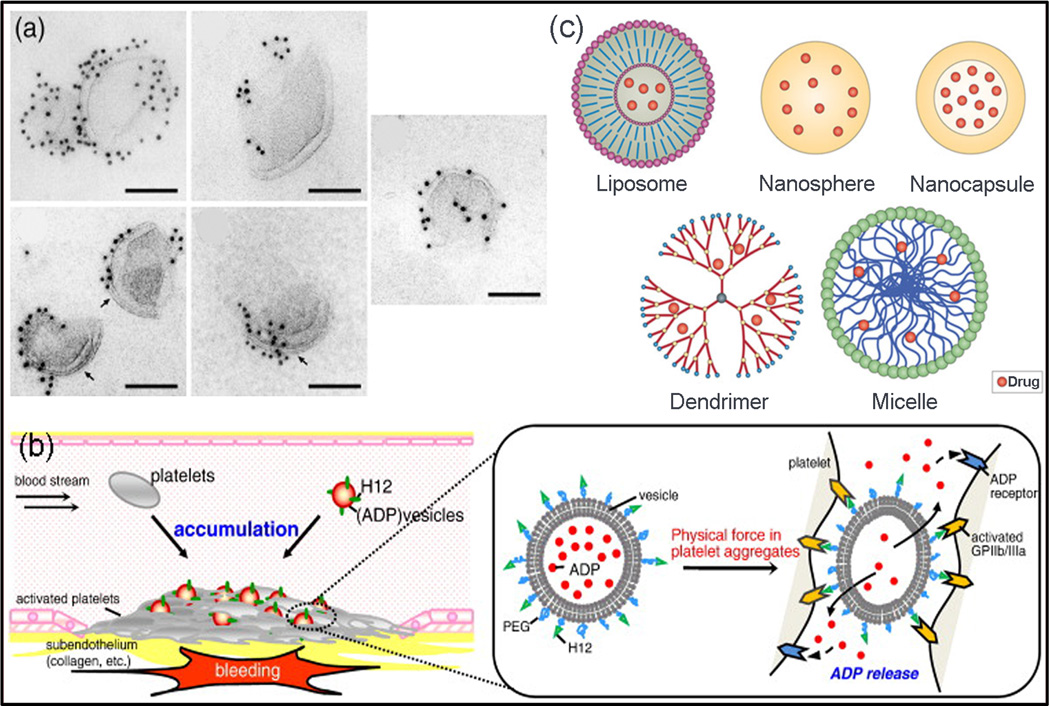

ADP is a platelet agonist that plays a role in stabilizing the platelet aggregation after their activation (Ware et al., 1987). Okamura et al. (Okamura et al., 2010) developed a platelet substitute with hemostatic activity by conjugating the phospholipid vesicles (PC) with a dodecapeptide (HHLGGAKQAGDV, H12) to encapsulate ADP. They prepared H12-(ADP)-vesicles with various membrane flexibilities by freeze-drying, hydration with ADP, and then extrusion using membrane filters with different pore sizes. Lamellarities of vesicles were controlled by gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperature of the lipid during extrusion. They showed that, by controlling vesicle membrane deformability (membrane flexibility and lamellarity), the ATP release and subsequently the hemostatic property of H12-(ADP)-vesicles can be tuned (Fig. 1) (Okamura et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of ADP release from H12-(ADP)-vesicles with distinctive membrane characteristics designed by Okamura et al. (a) Electron microscopic images of the H12-(ADP)-vesicles with different membrane flexibilities showing that the H12 molecules were bound to the vesicles, scale bars show 100 nm (Okamura et al., 2010). (b) ADP encapsulated vesicles (H12-(ADP)-vesicles) controlled their hemostatic abilities by tuning ADP release dependent on membrane properties. It was reported that ADP release increased when either membrane flexibility increased or lamellarity decreased (Okamura et al., 2010), (c) Schematic structure of nanocarriers used for drug delivery (Orive et al., 2009).

2.2 Adenosine delivery using polyethylene glycol (PEG)

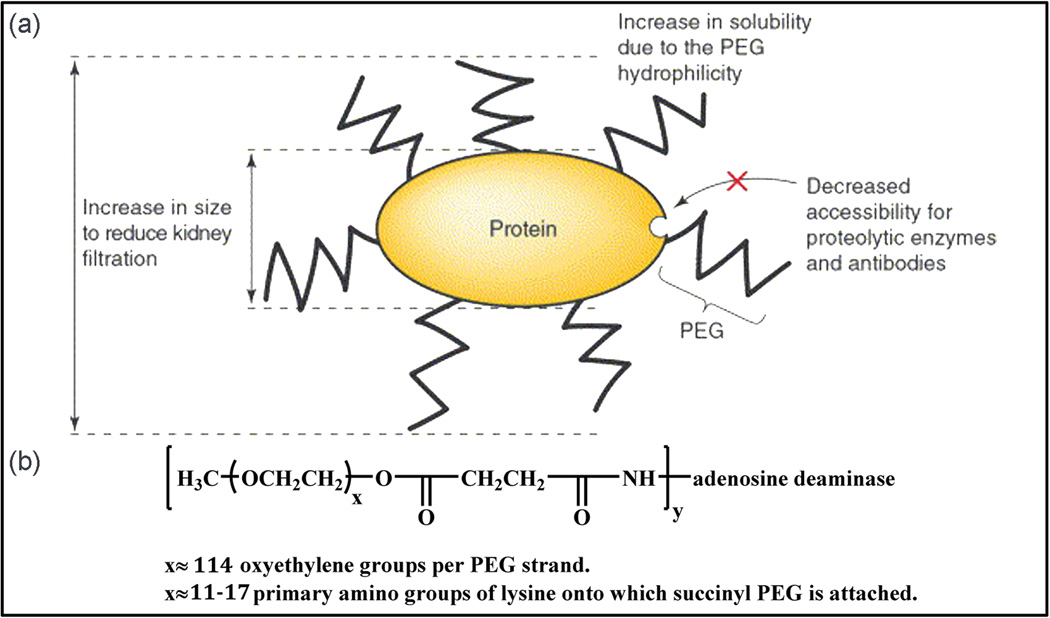

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency is a metabolic disorder that causes severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Bone marrow transplantation and intramuscular polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase (PEG-ADA) are the only available therapies for ADA deficiency (Lainka et al., 2005). PEG is amphiphilic, non-toxic, non-immunogenic, non-antigenic, and can be eliminated by urination. These characteristics along with low level of protein/cellular absorption have made PEG the most common synthetic material in polymer-based DDS. PEG has been approved by the FDA for intravenous (IV), oral, and dermal applications (Hooftman et al., 1996, Knop et al., 2010). In addition to utilization of PEG-based drug carriers, adenosine can be directly grafted to ADA to improve its half-life in vivo (Lainka et al., 2005). In 1981, Davis et al. developed a covalent coupling between PEG and ADA using cyanuric chloride agent. The circulating half-life of the modified ADA increased to 28 h (Davis et al., 1981). In PEGylation procedure (first introduced in 1970) numerous strands of PEG are attached covalently to another molecule, such as a drug or therapeutic protein (Hooftman et al., 1996, Knop et al., 2010, Veronese and Pasut, 2005). PEGylated bovine ADA (Adagen®, trade name for PEG-ADA or pegademase bovine) was approved by the FDA to enter the market in 1990 for intramuscular injection (Fig. 2) (1990, Levy et al., 1988, Hershfield, 1998, Booth and Gaspar, 2009). Adagen® has been used for the treatment of SCID in patients for whom bone marrow transplantation is not possible (Hershfield MS, 1995). PEG-ADA optimizes the therapeutic effect of ADA molecules by slowing its clearance and maintaining a high level of ADA activity by increasing its circulation half-life in plasma. PEG-ADA also reduces immunogenicity, decreases the enzymatic degradation of ADA molecules by protease, and limits its binding with host antibodies (Hershfield MS, 1995). Long-term improvement of the immune status has been reported with Adagen® treatment (Hershfield, 1998). Moreover, the side effects from ADA administration such as sensitization to erythrocyte antigens and virus transmission were not observed using PEG-ADA therapy in the patients with ADA deficiency (Levy et al., 1988).

Fig. 2.

(a) PEGylation shields the protein surface from degrading agents by steric hindrance, and increases the size of the conjugate to decrease kidney clearance (Veronese and Pasut, 2005). (b) In the structural formula of Adagen® bovine ADA covalently attached to numerous strands of monomethoxy PEG with molecular weight 5,000 (Hershfield, 1995).

So far, PEG-ADA has been successfully used in a few hundred patients worldwide and a couple of clinical studies have been reported on PEG-ADA treatment (Booth and Gaspar, 2009). Author (Hershfield et al., 1987) could significantly improve the cellular immune function, and increase circulating T lymphocyte count by injecting PEG-ADA in two children with adenosine deaminase deficiency and SCID (Hershfield et al., 1987). A clinical study on an ADA-deficit child performed by Bory et al. also showed that PEG-ADA therapy could increase the total number of lymphocytes and their response to non-specific mitogens significantly (Bory et al., 1991). Bax et al. (Bax et al., 2000) also investigated the entrapment of native ADA and PEG-ADA within human erythrocytes via hypo-osmotic dialysis procedure to improve the in vivo half-life of the enzyme. It was discovered that the entrapment efficiency for PEG-ADA was only 9% due to PEG side chains, while the entrapment efficiency for unmodified ADA was as high as 50%. However, the half-life of erythrocyte-entrapped PEG-ADA (20 days) was higher than those with native ADA (12.5 days). These values were significantly more prolonged than in vivo plasma PEG-ADA circulating half-life (3 – 6 days) (Bax et al., 2000). A similar clinical study performed by Lainka et al. (Lainka et al., 2005) resulted in an impressive immune reconstitution on a 14-month-old girl with ADA deficiency (Lainka et al., 2005).

Adenosine is currently used for the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease (adenosine echocardiography (Zoghbi et al., 1991)) and a high dose is required to exert cardio-protective effects. In clinical trials, however, adenosine causes hypotension and bradycardia (Horwitz et al., 1994). To reduce this associated hemodynamic consequences while administrating a high dose of adenosine, Takahama et al. (Takahama et al., 2009) encapsulated adenosine in PEGylated liposomes for the delivery of adenosine to ischemic hearts. The PEGylated liposomal adenosine was prepared by the hydration method with a mean diameter of 134 ± 21 nm. To study whether liposomal adenosine has stronger cardio-protective effects compared to the conventional method, the PEGylated liposomal adenosine were evaluated for myocardial accumulation and myocardial infarct during 3 h after 30 min of ischemia followed by reperfusion size in rats. The results showed that the liposomes were extensively taken up by the ischemic myocardium, but not by non-ischemic myocardium. PEG coating on liposomes could prolong their residence time in the blood (Papahadjopoulos et al., 1991). No significant effects on either mean blood pressure or heart rate even at high dose of 450 µg/kg/min were observed, indicating that intravenously administration of high doses of liposomal adenosine to the ischemic heart was safe (Takahama et al., 2009, Tissier et al., 2007).

Although PEG can protect the drugs from immune cells and has been extensively used in drug delivery, its inert characteristics result in low cellular uptake. In addition, PEG-based carriers should be decorated with other molecules to pass physiological barriers such as blood-brain-barrier, which add to the complexity of fabricating targeted drug carriers. Additionally, PEG is also non-biodegradable and if the carrier size is big (>10 µm), its clearance from the blood might be challenging.

2.3 Chitosan

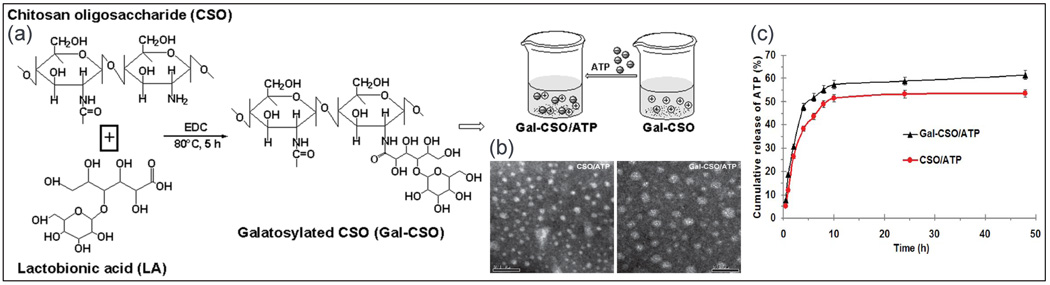

Chitosan-based nanocarriers are promising materials for drug encapsulation because of their high biocompatibility and biodegradability (Lee et al., 1995), high mucoadhesiveness (Lehr et al., 1992), and immunostimulating properties (Nishimura et al., 1986). As chitosan is only soluble in acidic solutions (pH < 6.5), low molecular water soluble chitosan oligosaccharide (CSO) was used by Zhu et al. (Xiu Liang et al., 2013) for ATP delivery. In their technique, lactobionic acid with a galactose group was conjugated to CSO using the freeze-drying technique (Chung et al., 2002). Galactosylated chitosan oligosaccharide (Gal-CSO) was then loaded with ATP in a drop-wise manner as the specific adhesive ligand to the asialoglycoprotein receptor of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Kang et al., 2012). The ATP-loaded nanoparticles exhibited low cytotoxicity when cultured with human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. ATP loaded nanoparticles had mean diameter of 51.0 ± 3.3 nm with drug loading and encapsulation efficiency of about 26%, and 89%, respectively. An initial burst release (~30%) of ATP occurred within the first 2 h in PBS while ~60% of ATP released after 48 h from Gal-CSO/ATP (Fig. 3). This method has been suggested as an intracellular drug delivery system for targeting carcinoma cell in hepatopathy, however additional in vivo study is required to confirm the efficacy (Xiu Liang et al., 2013).

Fig. 3.

(a) Schematic of Gal-CSO/adenosine triphosphate (ATP) formation. (b) TEM images of nanoparticles (left) CSO/ATP and (right) Gal-CSO/ATP showing the size range of 51.03 ± 3.26 nm (the bar is 0.1 µm). (c) In vitro cumulative release rate of ATP from nanoparticles in PBS exhibited the initial burst release attributed to the drug adsorbed on the surface of the nanoparticles (Xiu Liang et al., 2013).

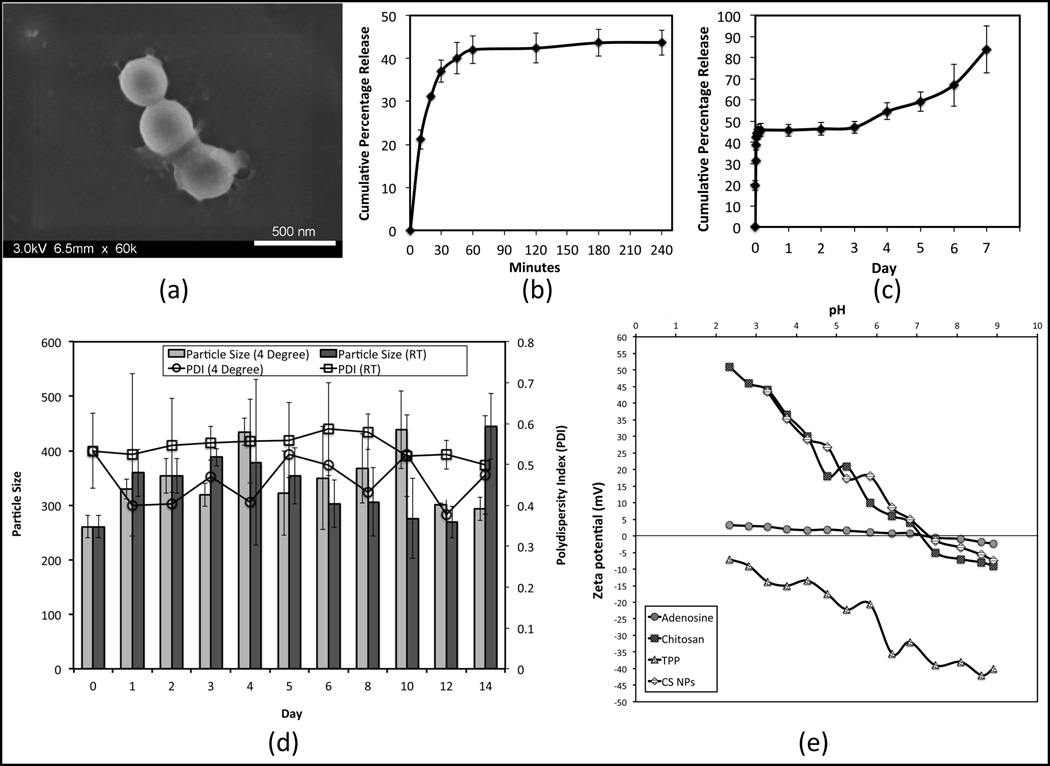

Author (Kazemzadeh-Narbat et al., 2015) encapsualted adenosine into the chitosan spherical nanoparticles (average size of 260.6 ± 20.1 nm, with zeta potential value of +29.2 ± 0.5 mV) using ionotropic gelation (5:1 chitosan:sodium tripolyphosphate mass ratio) for IV delivery. The nanoparticles had low encapsulation efficiency (3%), and loading capacity (20%) with almost 350% swelling in 6 h. The release mechanism showed a burst release, a plateau phase, followed by a steady release up to seven days with an excellent physical stability at room temperature and at 4 °C (Fig. 4) (Kazemzadeh-Narbat et al., 2015).

Fig. 4.

(a) The SEM micrograph of chitosan nanoparticles. (b) Short term adenosine release in PBS (pH 7.4), (c) long term. (d) Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) of adenosine loaded chitosan nanoparticles. (e) Isoelectric point and zeta potential changes with pH for the adenosine, chitosan, sodium tripolyphosphate, and nanoparticles (Kazemzadeh-Narbat et al., 2015).

In spite of all interesting characteristics of chitosan, it can trigger inflammatory response. Also, small size carriers might be absorbed through phagocytosis, which can result in uncontrolled release profile.

2.4 Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)

PLA, Poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), and their copolymer PLGA have been extensively studied as micro- and nano-carriers for several classes of drugs due to their high biocompatibility and tunable biodegradability (Bala et al., 2004). These polymers can also protect unstable compounds for a longer period of time. Similarly these carriers have been also used for adenosine delivery.

The N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA) is known as a drug with anti-ischemic properties for CNS, however because of its low stability in body CPA is unable to reach the brain (Simpson et al., 1992, Muller, 2000). Author (Dalpiaz et al., 2001) investigated the sustained delivery of CPA by encapsulating it into biodegradable PLA microspheres. The encapsulation method was based on emulsion–solvent evaporation. They reported the encapsulation efficiency of 1.1% for CPA encapsulated microspheres (0.11 mg/100 mg). The microspheres (21 ± 9 µm) released almost 92% of the encapsulated CPA using a column-type apparatus in 72 h in PBS (pH 7.4). This approach will maintain therapeutic doses of the CPA in the blood stream after intravenous administration (Dalpiaz et al., 2001).

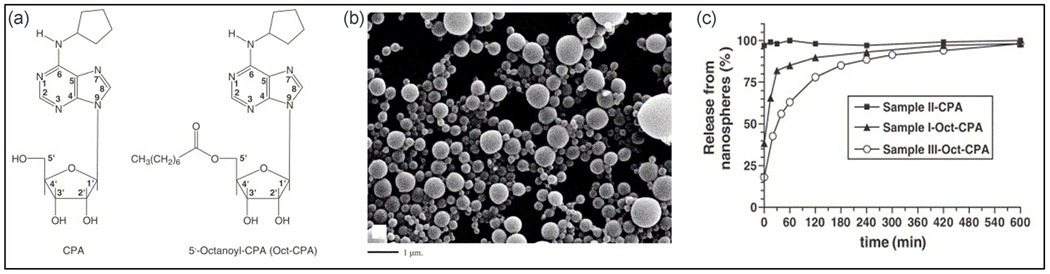

In the follow up study, Dalpiaz et al. (Dalpiaz et al., 2005) reported biodegradable PLA nanospheres as delivery systems for CPA and its pro-drug 5’-octanoyl-CPA (Oct-CPA). The PLA nanospheres were fabricated by double emulsion solvent evaporation method or nanoprecipitation, and the nanoparticles were collected by ultracentrifugagtion, gel filtration or through dialysis. The CPA loaded spherical nanoparticles prepared using the nanoprecipitation technique had average diameters of 210 ± 50 nm and the nanoparticles prepared using double emulsion solvent evaporation method had average diameters of 310 ± 95 nm. Although no encapsulation of CPA was obtained in either technique, Oct-CPA content in nanospheres were 0.1–1.1% w/w, with the encapsulation efficiency of 6–56%. All the Oct-CPA nanospheres had mean diameter of 220–270 nm except the nanoparticles recovered by ultracentrifugation, which exhibited mean diameter of 390 ± 90 nm. Almost 90% of the Oct-CPA was released within 4 h (Fig. 5) (Dalpiaz et al., 2005).

Fig. 5.

(a) Illustration of CPA and Oct-CPA chemical formulas, (b) SEM of Oct-CPA loaded nanospheres prepared by double emulsion solvent evaporation method, and (c) in vitro release of CPA and Oct-CPA from PLA nanospheres in phosphate buffer at 37°C developed by Dalpiaz et al. (Dalpiaz et al., 2005).

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) has also been investigated for encapsulating adenosine derivatives. As an example, a PEG scaffold loaded with PLGA has been used to encapsulate adenosine derivative for the treatment of spinal cord damages to stimulate the nerve regeneration and reconstitution of pathways (Maquet et al., 2001). The scaffold could support and guide nerve fibers, while local delivery of therapeutic accelerate the regeneration process (Maquet et al., 2001). Rooney et al. (Rooney et al., 2011) also used PLGA microsphere-loaded oligo (Rooney et al.) (OPF) hydrogel disc scaffolds to deliver dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (dbcAMP) to a transected spinal cord (Rooney et al., 2011). DbcAMP was encapsulated into PLGA microspheres using water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) double emulsion solvent evaporation (De Boer et al., 2010). The mixture of microspheres and OPF solution were then poured into glass molds and cross-linked by UV light into disc shape scaffolds. It was observed that by prolonged dbcAMP release over 42-day, axonal regeneration was inhibited and rescued in the presence of Schwann cells and MSCs respectively (Rooney et al., 2011).

Synthetic PLA- and PLGA-based nanocarriers are promising carriers for adenosine delivery; however, they are susceptible to phagocytosis, which can reduce their half-life. These nanocarriers can be functionalized with molecules that can make them specific to a target tissue. The release profile can also be tuned by size modification. One challenge associated with these carriers is their burst release that can prevent from maintaining a sustainable drug level over a long period of time.

2.5 Ethylene Vinyl Acetate (EVA)

Boison et al. used a synthetic EVA copolymer to deliver adenosine to the brain of kindled rats as a representation of human temporal lobe (McNamara et al., 1985, Boison et al., 1999). For this purpose, into the lateral brain ventricles of previously kindled rats, were implanted by 0.4 mm diameter polymer rods with height of 1 mm. It was demonstrated that EVA copolymer loaded with 20 % adenosine (w/w) could release 20–50 ng/day of adenosine inducing a sustained reduction of epileptic seizures for up to two weeks compared with control implants. The results indicated that focal delivery of adenosine might suppress epileptic seizures without causing cardiovascular or sedative side effects. The implants, however, were not degradable and therefore had to be removed after experiments (Boison et al., 1999).

2.6 Silk

Purified silk fibroin protein is an interesting candidate for adenosine delivery as silk is an FDA-approved, biocompatible, and mechanically strong polymer that degrades to nontoxic products. Furthermore, degradation of silk is tunable from weeks to years (Horan et al., 2005, Wenk et al., 2011). Although the focal adenosine delivery from silk implants precludes long-term clinical applications, it might be an alternative for short-term clinical trials prior to surgical resection. A silk-based adenosine delivery system can also be applied for preventative use in patients prone to developing epilepsy, such as those with traumatic brain injury (Szybala et al., 2009, Wilz et al., 2008b).

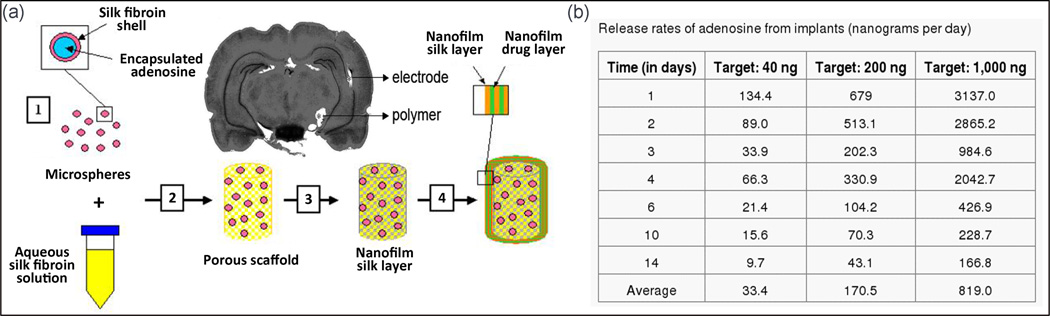

Wilz et al. (Wilz et al., 2008a), developed a hierarchically structured controllable silk-based delivery system for adenosine. They designed brain implants with adenosine delivery capability consisting of three systems, microspheres, macroscale films, and nanofilms with the nominal delivery rates of 0, 40, 200, and 1000 ng/day (Fig. 6). The rate and dose of adenosine release of their implant were tuned by changing the microspheres concentration, the concentration of adenosine in the macroscale films, and the quantity of nanofilm layers coating the porous scaffold system. Microspheres loaded adenosine were created in accordance with the methanol-based lipid template protocol (Wang et al., 2007a). To shape the final porous scaffold, the combination of silk solution and microspheres were embedded in a plastic container and incubated for 24 h at room temperature (Kim et al., 2005). Macroscale and nanofilm adenosine-loaded silk coatings were then applied on the scaffolds, alternatively (Hofmann et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2007b). These three systems were integrated into a single implantable silk rod (0.6–0.7 mm in diameter and 3–4 mm in height) (Fig. 6). The in vitro release experiments showed that all implants released adenosine with an initial burst with prolonged release close to the target rates for at least 14 days. The rate of adenosine release was defined by the numbers of capping layers (implant dip into silk solution), the thickness of nanofilm, and the silk crystallinity. The in vivo study was conducted on a rat kindling model in which seizures were provoked by repetitive short electrical stimulation of the hippocampus. It was observed that, silk-based polymer implants could effectively retard the epileptogenesis corresponding to the released dose of adenosine. Thus, in comparison to the control, the implant with 1000 ng/day adenosine release did not exhibit any seizures during the experiment time. However, seizures gradually resumed with progressive intensity as soon as drug release from the implants began to diminish (Wilz et al., 2008a).

Fig. 6.

(a) Schematic of four-step fabrication of silk-based adenosine releasing implants: (1) Microsphere loaded with adenosine. (2) Mixture of microspheres with silk solution, and embedding them in the form of porous scaffolds. (3) Scaffolds are soaked in the solution of silk and adenosine, and coated with macroscale drug-loaded film coating. (4) Alternating nanofilm deposition loaded with adenosine is coated. The polymer site at infra-hippocampal and the implantation channel of the electrodes are visible in the Nissl stained coronal brain section, 20 days after transplantation. (b) The release profile of adenosine from implants, no seizure was observed at 1000 ng/day adenosine release during the experiment time (Wilz et al., 2008a).

Szybala et al. (Szybala et al., 2009) combined this silk-based 3D porous scaffold with engineered human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) to release adenosine (Ren et al., 2007). Polymeric scaffolds designed to release 1000 ng/day adenosine were then implanted into the rat brains. It was observed that rats were fully protected from seizures up to ten days with sustained adenosine release. Silk-based adenosine implants exert potent anti-ictogenesis, with at least partial anti-epileptogenic effects (Szybala et al., 2009).

Pritchard et al. (Masino and Boison, 2013) coated the solid press-fit adenosine powder reservoirs (70 ± 5 mg) with silk fibroin by dipping technique to achieve sustained, zero-order release. By controlling the silk coating, they could achieve a linear, sustained adenosine release for up to 17 days from encapsulated coated reservoirs with eight layers of silk (8% w/v) (Pritchard et al., 2010). A release study on dissolvable silk films loaded with 0.5, 0.25, or 0.125 mg of adenosine per 0.2 mm2 film has shown that almost 80% of the adenosine load was released within 15 min in PBS at 37 °C (Masino and Boison, 2013).

In another study, silk microspheres loaded with adenosine were fabricated in accordance with the MeOH-based lipid (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC)) protocol (Wang et al., 2007c). The resulting cross-linked microspheres were less than 2 µm in diameter, and could be loaded with 85 mg of adenosine per mg of silk microspheres. Starting with a burst release, about 75% of the total loaded adenosine released within the first 24 h, with no significant release after 3 days (Masino and Boison, 2013, Wang et al., 2007c). They showed also that creating silk hydrogel (1 % (w/v) or 3 % (w/v)) by suspending microspheres in a sonication did not improve release profile in PBS (Wang et al., 2008, Masino and Boison, 2013). However, by suspending microspheres in aqueous-derived porous silk sponges, the release profile was improved from 3 to 7 days with a constant, zero-order delivery for the first 3 days (Masino and Boison, 2013). Also, the addition of silk coatings delayed the release of adenosine-loaded silk microspheres (Wang et al., 2007b, Masino and Boison, 2013). Adenosine-releasing silk microspheres can be applied by minimally invasive injection.

There is a growing interest towards the use of silk in biomedical applications. However, the challenges toward its use in drug delivery include potential inflammation and the burst release of the drug, which prevent the accurate estimation of the drug level.

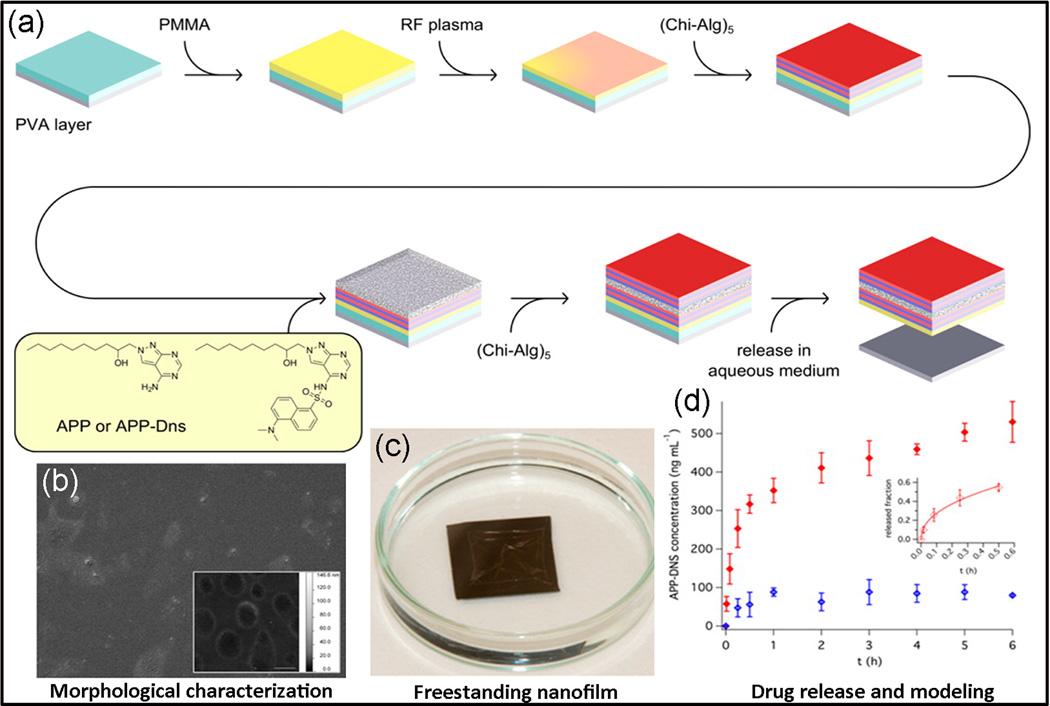

2.7 Layer-by-Layer Assembly

Layer-by layer (LbL) assembly technique is a novel approach to fabricate multilayered coatings using sequential electrostatic adsorption of polyelectrolytes (Decher, 1997). Using LbL, an ultrathin PMMA/polysaccharides nanofilm was developed by Riva et al. (Riva et al., 2013) to encapsulate adenosine deaminase inhibitor. Inhibition of adenosine deaminase results in elevation of local adenosine concentration, thereby decreasing the inflammatory effect (Ye and Rajendran, 2009). To fabricate the polymeric nanofilm, chitosan/sodium alginate (Chi-Alg) was deposited alternatively using spin-assisted LbL method onto a PMMA structural layer. The multilayer nanofilm was subsequently loaded with an adenosine deaminase inhibitor and its fluorescent dansyl derivate by a casting deposition technique (Fig. 7). In aqueous medium the nanofilm released 91.6% of drug within 6 h through diffusion, degradation, and drug–polymer liberating, following the Korsmayer−Peppas model in which PMMA acts as a release barrier. This ultrathin platform had a very low surface roughness, with thickness of about 200 nm. Combination of anti-inflammatory activity, high biocompatibility, and adhesion of nanofilm to wet tissue/mucosal surface make this a promising nanopatch for the treatment of diseases involve chronic inflammation (Riva et al., 2013).

Fig. 7.

(a) Fabrication procedure of a free-standing layer-by-layer polymeric nanofilms (thickness < 200 nm) made of PMMA (as a barrier) and a polysaccharides assembly incorporated with an adenosine deaminase inhibitor. A thin film of PMMA first was treated with plasma then chitosan and sodium alginate was deposited on the film using spin-assisted LbL assembly. (b,c) The PMMA/LbL nanofilms characterization indicates low surface roughness, which were between 1–2 nm for drug loaded nanofilms and less than 1 nm for blank nanofilm. (d) The release was based on a diffusion similar to the Korsmayer–Peppas model (Riva et al., 2013).

2.8 Silica Nanosphere-Based Adenosine Delivery

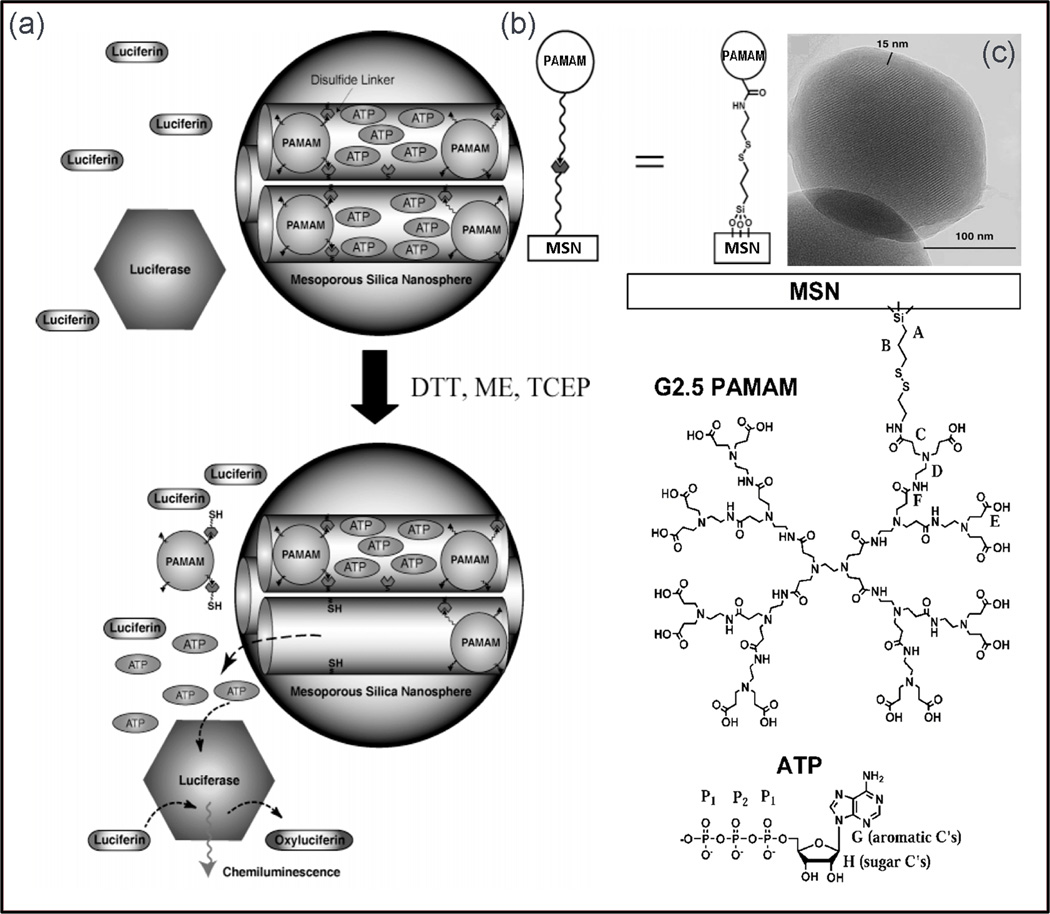

The mesoporous silica nanospheres (MSN) have well-defined surface properties with very large surface area, and stable mesoporous structures that allow tuning pore sizes and volumes. These attractive features are ideal for encapsulation of therapeutic molecules (Stein et al., 2000, Sayari and Hamoudi, 2001). The encapsulation of drug molecules in polymer-based delivery systems is based on adsorption or entrapment. However, MSNs are capable of encapsulating the drugs inside the porous framework by covalently capping the mesopores with caps which are chemically removable, such as size-defined cadmium sulfide (CdS) nanocrystals, or via a disulfide linkage of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers (PAMAM) to physically seal the drugs from leaching out (Lai et al., 2003, Gruenhagen et al., 2005). Lai et al. (Lai et al., 2003) reported a mesoporous silica-based delivery system that would control the release by using trigger agents (various disulfide bond-reducing agents) as “uncapping triggers”, such as mercaptoethanol (ME), and dithiothreitol (DTT). MSNs with mean pore diameter of 2.3 nm and average particle size of 200 nm were employed as reservoirs to soak up ATP solutions. To cap the openings of the mesopores, amidation reaction was applied using CdS (Chan and Nie, 1998), and the release rate was regulated by the concentration of the trigger agents (DTT or ME). The CdS-capped MSN delivery system released negligible ATP (less than 1.0%) in PBS over a period of 12 h. However, after 3 days of the DTT triggering, 28.2% (1.3 µmol) of the ATP molecules diffused away (Lai et al., 2003).

Gruenhagen et al. (Gruenhagen et al., 2005) conducted a similar study using ATP-loaded MSN material capped with PAMAM and CdS. By using real-time chemiluminescence imaging, chemiluminescence signals from ATP release were collected and pulse-type release kinetics was observed due to uncapping of CdS-capped particles, while the ATP release from PAMAM-capped MSN was more gradual and plateau-like profile (Fig. 8) (Gruenhagen et al., 2005).

Fig. 8.

(a) Schematic of mesoporous silica nanosphere encapsulating ATP molecules and illustration of real-time imaging of ATP chemiluminescence developed by Gruenhagen et al. (b) The ATP release was tuned by controlling uncapping triggers and the emitted chemiluminescence signal was collected for in vitro release study. (c) TEM images of PAMAM dendrimer-capped MSN shows the visible PAMAM dendrimer coating encapsulating the particle (Gruenhagen et al., 2005).

3 Other Adenosine Delivery Systems

3.1. Cell-Based Adenosine Delivery

Cell-based delivery is an alternative to micro- and nano-particles in which, various cells are engineered to act as biological drug-delivery systems (Dorey, 2011). Cell and gene therapies have been explored for epilepsy treatment on a local level (Boison, 2007b, Loscher et al., 2008, Raedt et al., 2007, Shetty and Hattiangady, 2007, Boison and Stewart, 2009). Elevation of adenosine kinase and reduction of adenosine have been proven to increase seizure susceptibility in established epilepsy. This phenomenon can be controlled by increasing the adenosine level (Boison, 2007a, Li et al., 2007, Huber et al., 2001, Boison, 2007b, Li et al., 2008). Several studies have demonstrated that kindled seizures in rats could be inhibited by focal paracrine delivery of adenosine from encapsulated cells without overt side effects. These studies encapsulated engineered fibroblasts, myoblasts or stem cells using genetic disruption of the Adk gene to release adenosine (Boison et al., 2002a, Guttinger et al., 2005a, Guttinger et al., 2005b, Huber et al., 2001, Boison, 2007a, Li et al., 2007, Boison, 2007b).

Hughes et al. (Hughes et al., 1994) attempted to encapsulate cell lines within immunoprotective microcapsules before implantation by fusing a signal sequence to ADA to prevent immunosuppression in nonautologous hosts. They engineered the transfected mouse fibroblasts/myoblasts by enclosing them in microcapsules fabricated from hydrogel and alginate-poly-L-lysine. It was observed that the cells successfully secreted adenosine deaminase (ADA) from the microcapsules and had viability over 5 months (Hughes et al., 1994).

Huber et al. (Huber et al., 2001) engineered the baby hamster kidney (BHK) fibroblasts to release adenosine. In this technique, the cells were rendered ADK deficient (shown as Adk−/−) by inactivating the adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase (adenosine-metabolizing enzymes) before being used for adenosine delivery. Adenosine-releasing cells were encapsulated into semipermeable polyethersulfone (PES) hollow fibers with 7 mm length, 0.5 mm inner diameter, and wall thickness of 50 µm (Huber et al., 2001). A partial epilepsy model was used for the in vivo study, in which the cells were implanted into the lateral brain ventricles of electrically kindled rats. In vivo release rate from the implanted fibers was comparable to its biological production rate, in the range of 20 to 50 ng/day. It was observed that electrically-induced seizures were suppressed for up to 2 weeks by the local paracrine adenosine (concentrations < 25 nM) without any overt side effects such as sedation or ataxia (Boison et al., 1999). About 90% of the transplanted cells were still in the host brain three days after transplantation, which resulted in 100% seizure suppression. The accumulation of released adenosine was considered to be unlikely, as the adenosine was taken up into cells by equilibratory transporters (Huber et al., 2001).

By using the same ADK-deficiency technique (Huber et al., 2001, Fedele et al., 2004) Güttinger et al. (Guttinger et al., 2005b) could induce the release of adenosine from mouse C2C12 myoblasts with the aim to achieve long-term seizure suppression. In their work, semipermeable polyethersulfone polymer hollow-fiber membranes with size of 5 mm length, 0.5 mm inner diameter, and wall thickness of 50 Am containing a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix were loaded with genetically modified myoblasts (Huber et al., 2001). One week after grafting the implants into the brain ventricles of epileptic kindled rats, all rats showed 100% protection from convulsive seizures for up to 8 weeks (Guttinger et al., 2005b). It was also observed that disruption of adenosine kinase after implantation did not inhibit cellular differentiation or functional activity (Guttinger et al., 2005a).

Although localized delivery of adenosine from cells appears promising for treatment of epilepsy, long-term adenosine delivery is of great importance toward their clinical application. One limitation regarding long-term delivery of adenosine from the encapsulated cells is the reduced life expectancy of cells (Huber et al., 2001). Local release of adenosine by engineered stem cell implants might be a solution for epilepsy therapy (Fedele et al., 2004, Boison and Stewart, 2009, Boison, 2007b, Loscher et al., 2008, Raedt et al., 2007, Shetty and Hattiangady, 2007). Anticonvulsant properties of adenosine, long-term survival potential, and capability of stem cells in repairing the injured brain make the stem cell-derived brain implants a promising therapeutic tool to achieve focal long-term delivery of adenosine (Wu et al., 2009, Guttinger et al., 2005a, Huber et al., 2001). Unlike encapsulated cell grafts that release adenosine based on only paracrine action, it is believed that the release mechanism of stem cell-derived implants is a combination of paracrine effects with network interactions (Boison, 2009a, Ruschenschmidt et al., 2005, Huber et al., 2001, Guttinger et al., 2005b).

In another work by Fedele et al. (Fedele et al., 2004) on mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, both alleles of ADK were disrupted (Adk−/− ES) using homologous recombination. By differentiating Adk−/− ES cells into mature astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Studer et al.), sufficient quantity of adenosine release (up to 40.1 ± 6.0 ng per 105 cells/h) was obtained which was enough for seizure suppression (Fedele et al., 2004). A similar study with astrocytes derived from fetal neural progenitor cells isolated from Adk−/− mouse could release 47 ± 1 ng per 105 cells per 24 h (Van Dycke et al., 2010b).

Li et al. (Li et al., 2007, Li et al., 2008) conducted a study on the following adenosine – cellular implants; i) wild-type (Adk+/+) and ii) genetically altered (Adk−/−) embryonic stem cells. The cells were then differentiated into neural precursor cells (NPs), and Adk+/+ BHK (with normal ADK expression), and adenosine releasing Adk−/− BHK-AK2 (totally lacking ADK expression) cell implants. They grafted the implants into the hippocampus of rats and compared their antiepileptogenic effects. The following order of therapeutic efficacy retard kindling development was observed: Adk−/− NP > Adk−/− BHK-AK2 > Adk+/+ NP > Adk+/+ BHK, indicating the superiority of embryonic stem cell-derived brain implants in terms of adenosine releasing, and sustained protection from seizures. In conclusion, the epileptogenesis and the occurrence of generalized seizures were reduced by adenosine releasing from stem cell-derived nanoparticles during kindling development. Considering the superior anticonvulsant effect of stem cell-mediated delivery over paracrine adenosine release from fibroblasts, it is speculated that the stem-cell grafts might be a potential treatment for long-term seizure suppression (Li et al., 2007, Li et al., 2008).

Van Dycke et al. isolated Adk−/− neural stem cells from fetuses of ADK knockout mice before they die due to hepatic steatosis within 14 day (Boison et al., 2002b, Van Dycke et al., 2010b) and measured the quantity of secreted adenosine in culture medium and evaluated their differentiation potential (Van Dycke et al., 2010c, Van Dycke et al., 2010b). It was observed that the amount of adenosine released from both non-differentiated and differentiated fetal Adk−/− cells was enough for suppressing refractory epilepsy.

To improve the duration of adenosine release from Adk−/− ES cells, Uebersax et al. (Uebersax et al., 2006) studied the adenosine release potential of ES cells cultured on three different substrates (1) poly(L-ornithine), (2) silk-fibroin, and (3) type I collagen coated tissue culture plastic. Two different types of culture media were used for the study, 1) proliferation medium with growth factors, 2) differentiation medium without growth factors. Higher cell proliferation and lower metabolic activity were observed on collagen and poly(L-ornithine) substrates compared to SF. Compared to wild-type control cells, Adk−/− ES cultured on polymeric substrates, released higher concentration of adenosine (>20 ng/ml). The results showed that the differentiation of Adk−/− ES cells into astrocytes and subsequently release of adenosine was efficient on SF. Thus, SF might be a suitable candidate for Adk−/− ES encapsulation (Uebersax et al., 2006).

The second generation of adenosine-releasing cells are engineered human stem cells (Ren et al., 2007, Boison, 2009b). This method includes knockdown of ADK by gene expression with lentiviral micro-RNA vector in hMSCs and human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). This technique resulted in up to 80% ADK-knockdown for hMSCs (Ren et al., 2007). hMSCs have advantages over cell grafts as they allow the transplantation of autologous cells, and they can be induced to neuronal differentiation. Lentiviral transduction of hMSCs with anti-ADK miRNA resulted in 8.5 ng/mL adenosine release in medium during 105 cells incubation for 8 h (Ren et al., 2007). Boison et al. (Boison, 2009b, Ren et al., 2007), showed that engineered hMSCs grafted into the mouse hippocampus were potent anticonvulsant and could reduce acute injury (reduction in neuronal cell loss up to 65%), chronic seizures and seizure duration up to 35%. Knockdown of ADK was observed after applying similar lentiviral micro-RNA vector in hESCs (Boison, 2009b). It was reported that release of adenosine from encapsulated cell grafts is generally effective in seizure control with limited duration of action and is independent of seizure frequency (Boison et al., 2002a). Li et al. (Li et al., 2009) demonstrated that chronic seizures reduced in a post-status epilepticus model as a proof of-feasibility study in the development of therapeutic hMSC/silk-scaffolds (Uebersax et al., 2006). After grafting the engineered hMSCs into infrahippocampal fissures of models of focal spontaneous seizures, it was observed that the intensity of seizure significantly reduced (Li et al., 2009).

Cell-based adenosine delivery has shown promising results for treatment of a range of CNS disorders and can enter clinical trials if autologous cells are used. However, the use of genetically modified cells or non-autologous cells carry the risk of inflammation or other long term side effects which can cause other complications. Thus, future animal trials on larger animals are required to characterize the long term effect of such treatments.

3.2. Pump/Inhaler-Based Delivery

Cell-based adenosine-releasing systems have extensively been researched for treatment of epilepsy (Boison et al., 2002a). This approach, however, suffers from several limitations such as lack of established efficacy, distribution of the drug throughout the whole brain and cerebrospinal fluid rather than local seizure focus, and the need for immunosuppression.

One approach to avoid major side effects is local delivery using pumps. Micropumps in drug delivery are electronically activated devices with usually a refillable drug reservoir that meter continued release (LaVan et al., 2003). Van Dycke et al. exhibited the antiseizure effect of sustained adenosine delivery (0.23 µl/h) via osmotic minipumps in the hippocampi of rats with spontaneous seizures (Van Dycke et al., 2010a). They demonstrated that sustained delivery of high concentration of adenosine (33 mg per day) could lead to a significant reduction of convulsive and non-convulsive seizures without side effects, and a continuous decrease in seizure frequency (Van Dycke et al., 2010a).

Another suggested administration method for adenosine is dry powder inhalation. Administration of dry powder adenosine by inhaler was found to be very effective due to shorter administration time and more consistent delivery over the entire dose range. Lexmond et al. suggested this method as an alternative to nebulisation of adenosine 5’-monophosphate (AMP) in bronchial challenge testing. They formulated 100% pure adenosine powder and adenosine and lactose diluent using spray drying method. Several improvements were observed in their technique in compared to AMP method performed on asthmatic subjects (Lexmond et al., 2014).

Pump-based systems can facilitate continuous local and intravenous administration of adenosine. However, they cannot help with its short half life. Thus, in case that adenosine is employed for treatment of internal organs such as brain or heart, they should release encapsulated adenosine with longer half life.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Local delivery of adenosine and its derivatives offers enhanced efficacy, cost-efficiency and reduction or elimination of unwanted side-effects for treatment of chronic wounds, severe immunodeficiency diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, epilepsy, diagnosis of ischemic heart disease and early hepatic disease, spinal cord damages (Maysinger and Morinville, 1997, Menei et al., 1993, Gutman et al., 2000). Several methods have recently been utilized for local delivery of adenosine, including synthetic adenosine-releasing polymers/liposomes, encapsulated adenosine-releasing cells, pump-based delivery, and other approaches. However, no system currently exists to offer controllable, sustained, long-term adenosine delivery through fully degradable implants. Moreover no research has been done on smart delivery to release adenosine in a targeted area (e.g. brain) without interfering with other organ’s function (e.g. heart).

Polymer-based adenosine delivery systems are relatively safe and can prolong the release time and half-life of the drug. These carriers can also be used for target delivery if properly designed. On the other hand, the needs for invasive surgical procedure, local effects, and issues with their long-term effectiveness have limited their clinical use. Although long delivery durations are more difficult to achieve with polymer implants as compared to stem-cell based delivery, it seems that the efficacy of silk drug delivery implants for local delivery of neurological drugs have potential to be rapidly translated from animal studies to clinical trials (Lothman and Williamson, 1994, McNamara et al., 1985).

Stem cell-based adenosine delivery systems are capable of repairing the damaged network beside the paracrine release advantage. Moreover, the cells can be injected, bringing wide-spread delivery potential focal delivery of adenosine via stem or progenitor cells might be an alternative for treatment of refractory patients with epilepsy, however in this technique cell survival after transplantation is challenging. The benefits of stem cell-based delivery might evolve into an exciting generation for future research, for instance cellular delivery systems using neural stem cells or myotubes to achieve improved long-term viability (Boison et al., 2002a, Li et al., 2007, Raedt et al., 2009, Turner and Shetty, 2003, Zaman et al., 2001). However, the long-term effectiveness/viability of cell-based systems, survival of stem cells, network interaction and immunosuppression issues for non-autologous cell sources will challenge adenosine-based stem cell therapy translation into clinical use (Boison, 2009a, Ruschenschmidt et al., 2005, Guttinger et al., 2005b, Ren et al., 2007). In addition, it should be taken into consideration that the rat-kindling model used in most epilepsy treatment experiments is just a basic model for epileptogenesis and by no means reflects the entire histopathological changes in human epilepsy, which is a chronic disorder with a need for lifelong treatment (Lothman and Williamson, 1994, McNamara et al., 1985).

Although the ATP delivery systems are in early evaluation stage, they have shown very promising results for skin wound healing especially for chronic wounds, such as diabetic wounds, and pressure ulcers (Wang et al., 2009b, Chien, 2010). However, the significant difference between mechanisms of wound healing between humans and rodents should be considered (Galiano et al., 2004). In addition, the validity of some evaluations using immunodeficient mice should be questioned (Chiang et al., 2007).

Focal delivery of adenosine via infusion from nondegradable implantable mini pumps is promising. This approach may be limited by complications including the need for cyclic refilling or replacement during the lifetime of an epilepsy patient, mechanical failure, obstruction, and infection (Wang et al., 2002, Barcia and Gallego, 2009). A future option for clinical use of pump systems may be the steady local release of low concentrations of adenosine (Elger and Lehnertz, 1998, Boison et al., 2002a). An interesting concept for future adenosine delivery can be the emerging lab-on-a-chip technology. This approach employs advanced micro- and nanotechnologies that can fit into a microchip creating a compact integration of microdevices and microfluidics for precise and controlled drug delivery (Nguyen et al., 2013, Khademhosseini et al., 2006, Ghaemmaghami et al., 2012, Khademhosseini and Langer, 2006, Suh et al., 2004, Kang et al., 2008, Ling et al., 2007, Riahi et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Summary of adenosine-associated delivery systems

| System | Advantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle-Based techniques | Liposomes | Prolonged release (up to two months). |

Low entrapment efficiency |

| PEG /PEGylated liposomal |

Decreasing the enzymatic degradation, improving the cellular immune function |

Very low entrapment efficiency, low cellular uptake, nonbiodegradable |

|

| Chitosan | Biocompatible and biodegradable, high mucoadhesiveness, immunostimulating properties |

Potential inflammation | |

| PLA/PLGA | Highly biocompatible, Biodegradable |

Burst release and non- sustainable short term release |

|

| EVA | Up to 2 weeks sustained release |

Nondegradable | |

| Silk | Biocompatible, mechanically strong, tunable degradation to nontoxic products |

Burst release, potential inflammation |

|

| Silica Nanosphere | High encapsulation efficiency, porous structure |

Nondegradable | |

| Layer-by-Layer assembly |

Tunable release kinetics, biodegradable |

Complex fabrication process |

|

| Other | Cell-Based | Sustained long term release, biocompatible |

Potential inflammation, lack of established efficacy, distribution of the drug throughout the whole brain and cerebrospinal fluid, cell viability |

| Pump/Inhaler- Based |

Steady continued local release |

Need for cyclic refilling/replacement, mechanical failure, obstruction, and infection |

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (EFRI-1240443), IMMODGEL (602694), and the National Institutes of Health (EB012597, AR057837, DE021468, HL099073, AI105024, AR063745).

References

- Adagen® [package insert]. [Google Scholar]

- Agteresch HJ, Dagnelie PC, van den Berg JWO, Wilson JHP. Adenosine triphosphate - Established and potential clinical applications. Drugs. 1999;58(2):211–232. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agteresch HJ, Dagnelie PC, van der Gaast A, Stijnen T, Wilson JH. Randomized clinical trial of adenosine 5 '-triphosphate in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(4):321–328. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.4.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: Entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303(5665):1818–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur E, Baue EF, Donald E, Fry . Multiple Organ Failure: Pathophysiology, Prevention, and Therapy. Vol. 88. New York: Springer; 2000. p. 712. [Google Scholar]

- Bala I, Hariharan S, Kumar M. PLGA nanoparticles in drug delivery: The state of the art. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 2004;21(5):387–422. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v21.i5.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. In: Conn PM, Sealfon SC, editors. Methods in Neurosciences. Vol. 25. 1995. pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Barcia JA, Gallego JM. Intraventricular and Intracerebral Delivery of Anti-epileptic Drugs in the Kindling Model. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax BE, Bain Md Fau, Fairbanks LD, Webster AD, Chalmers RA, Chalmers RA. In vitro and in vivo studies with human carrier erythrocytes loaded with polyethylene glycol-conjugated and native adenosine deaminase. Br J Haematol. 2000;109(3):549–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli L. Adenosine system in the heart. Drug Dev. Res. 2004;28:263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Berne RM. The role of adenosine in the regulation of coronary blood flow. Circulation Research. 1980;47(6):807–813. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund A. Cell replacement strategies for neurodegenerative disorders. Chadwick DJ, Goode JA: 2000. pp. 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Scheurer L, Tseng JL, Aebischer P, Mohler H. Seizure suppression in kindled rats by intraventricular grafting of an adenosine releasing synthetic polymer. Experimental Neurology. 1999;160(1):164–174. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Scheurer L, Zumsteg V, Rulicke T, Litynski P, Fowler B, Mohler H. Neonatal hepatic steatosis by disruption of the adenosine kinase gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(10):6985–6990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092642899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Huber A, Padrun V, Deglon N, Aebischer P, Mohler H. Seizure suppression by adenosine-releasing cells is independent of seizure frequency. Epilepsia. 2002;43(8):788–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.33001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine kinase, epilepsy and stroke: mechanisms and therapies. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;27(12):652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Cell and gene therapies for refractory epilepsy. Current Neuropharmacology. 2007;5(2):115–125. doi: 10.2174/157015907780866938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine-based cell therapy approaches for pharmacoresistant epilepsies. Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2007;4(1):28–33. doi: 10.1159/000100356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D, Stewart KA. Therapeutic epilepsy research: From pharmacological rationale to focal adenosine augmentation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;78(12):1428–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Adenosine augmentation therapies (AATs) for epilepsy: Prospect of cell and gene therapies. Epilepsy Research. 2009;85(2–3):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boison D. Engineered Adenosine-Releasing Cells for Epilepsy Therapy: Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: An inflammatory disease? Kidney International. 2004;66(2):480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, Gaspar HB. Pegademase bovine (PEG-ADA) for the treatment of infants and children with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) Biologics. 2009;3:349–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bory C, Boulieu R, Souillet G, Hershfield MS. Polyethylene glycol adenosine deaminase a new adenosine deaminase deficiency therapy interest of deoxy atp determination for therapeutic monitoring. Therapie. 1991;46(4):323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Knight GE. Jeon KW, editor. Cellular distribution and functions of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. International Review of Cytology - a Survey of Cell Biology International Review of Cytology-a Survey of Cell Biology. 2004:31–304. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)40002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WCW, Nie SM. Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive nonisotopic detection. Science. 1998;281(5385):2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang B, Essick E, Ehringer W, Murphree S, Hauck MA, Li M, Chien S. Enhancing skin wound healing by direct delivery of intracellular adenosine triphosphate. American Journal of Surgery. 2007;193(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S. Intracellular ATP delivery using highly fusogenic liposomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;605:377–391. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-360-2_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TW, Yang J, Akaike T, Cho KY, Nah JW, Kim SI, Chong Su Cho. Preparation of alginate/galactosylated chitosan scaffold for hepatocyte attachment. Biomaterials. 2002;23(14):2827–2834. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak M, Komoszyński M, Wojtczak A. Adenosine A2A receptors in Parkinson’s disease treatment. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4(4):305–312. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpiaz A, Scatturin A, Pavan B, Biondi C, Vandelli MA, Forni F. Poly(lactic acid) microspheres for the sustained release of a selective A1 receptor agonist. Journal of Controlled Release. 2001;73(2–3):303–313. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpiaz A, Leo E, Vitali F, Pavan B, Scatturin A, Bortolotti F, Manfredini S, Durini E, Forni F, Brina B, Vandelli MA. Development and characterization of biodegradable nanospheres as delivery systems of anti-ischemic adenosine derivatives. Biomaterials. 2005;26(11):1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash AK, Cudworth GC. Therapeutic applications of implantable drug delivery systems. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1998;40(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(98)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Abuchowski A, Park YK, Davis FF. Alteration of the circulating life and antigenic properties of bovine adenosine deaminase in mice by attachment of polyethylene glycol. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1981;46(3):649–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson RMC. Data for Biochemical Research. 3rd. Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer R, Knight Am, Spinner RJ, Malessy MJ, Yaszemski MJ, Yaszemski MJ, Windebank AJ. In vitro and in vivo release of nerve growth factor from biodegradable poly-lactic-co-glycolic-acid microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;95(4):1067–1073. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decher G. Fuzzy nanoassemblies: Toward layered polymeric multicomposites. Science. 1997;277(5330):1232–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Dorey E. Cell Based Delivery. Nat Biotech. 2001:19. [Google Scholar]

- Drury AN, Szent-Györgyi A. The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. Journal of Physiology. 1929;68(3):213–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1929.sp002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV. Adenosine and suppression of seizures. Advances in neurology. 1999;79:1001–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecke D, Fischer B, Reiser G. Diastereoselectivity of the P2Y11 nucleotide receptor: mutational analysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:1250–1255. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger CE, Lehnertz K. Seizure prediction by non-linear time series analysis of brain electrical activity. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10(2):786–789. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulds D, Chrisp P, Buckley MMT. Adenosine An evaluation of its use in cardiac diagnostic procedures, and in the treatment of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Drugs. 1991;41(4):596–624. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199141040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele DE, Koch P, Scheurer L, Simpson EM, Mohler H, Brüstle O, Boison D. Engineering embryonic stem cell derived glia for adenosine delivery. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;370(2–3):160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigl EO. Berne's adenosine hypothesis of coronary blood flow control. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2004;287(5):1891–1894. doi: 10.1152/classicessays.00003.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: Opportunities and challenges. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(3):161–171. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman MB, Stone GW, Jackson EK. Role of adenosine as adjunctive therapy in acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular Drug Reviews. 2006;24(2):116–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenberg S, Wahlgren M, Reslow M, Axelsson A. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—A review. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2011;415(1–2):34–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Chen JF, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P, Vaugeois JM. Adenosine and brain function. International Review of Neurobiology. 2005;63:191–270. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(05)63007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14(7):1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Müller C. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors-An update. Pharmacological Reviews. 2011;63(1):1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB. Adenosine—a physiological or pathophysiological agent? Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2014;92(3):201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielian AG. Solubility of adenosine in concentrated salt solutions. Biofizika. 1977;22(5):789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajdos A. Letter: A.M.P in porphyria cutanea tarda. Lancet. 1974;1(7849):163. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiano RD, Michaels J, Dobryansky M, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Quantitative and reproducible murine model of excisional wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2004;12(4):485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami AM, Hancock MJ, Harrington H, Kaji H, Khademhosseini A. Biomimetic tissues on a chip for drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2012;17(3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghofrani HA, Wiedemann R, Rose F, Olschewski H, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Combination therapy with oral sildenafil and inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(7):515–522. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-7-200204020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Sharma SK. Uptake of liposomally entrapped adenosine-3 '-5 '-cyclic monophosphate in mouse brain. Neurochemical Research. 2004;29(2):441–446. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000013749.65266.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenhagen JA, Lai CY, Radu DR, Lin VSY, Yeung ES. Real-time imaging of tunable adenosine 5-triphosphate release from an MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanosphere-based delivery system. Applied Spectroscopy. 2005;59(4):424–431. doi: 10.1366/0003702053641513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, von Kügelgen I, Moro S, Kim YC, Jacobson KA. Evidence for the recognition of non-nucleotide antagonists within the transmembrane domains of the human P2Y1 receptor. Drug Devel Res. 2012;57:173–181. doi: 10.1002/ddr.10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman RL, Peacock G, Lu DR. Targeted drug delivery for brain cancer treatment. Journal of Controlled Release. 2000;65(1–2):31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttinger M, Fedele D, Koch P, Padrun V, Pralong WF, Brüstle O, Boison D. Suppression of kindled seizures by paracrine adenosine release from stem cell-derived brain implants. Epilepsia. 2005;46(8):1162–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.61804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttinger M, Padrun V, Pralong WF, Boison D. Seizure suppression and lack of adenosine A(1) receptor desensitization after focal long-term delivery of adenosine by encapsulated myoblasts. Experimental Neurology. 2005;193(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler CE, Fray R, Perkin GD, Woinarski J. Radiculomyelopathy associated with herpes simplex genitalis treated with adenosine arabinoside. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1983;59(692):388–389. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.59.692.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasko G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. 2008;7(9):759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield MS, Buckley RH, Buckley RH, Greenberg ML, Melton AL, Schiff R, Schiff R, Hatem C, Kurtzberg J, Markert ML, Kobayashi RH, Kobayashi AL. Treatment of adenosine deaminase deficiency with polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(10):589–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703053161005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield MS, Mitchell BS. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 7th. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1995. Immunodeficiency diseases caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency and purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency. [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield MS. Adenosine deaminase deficiency: Clinical expression, molecular basis, and therapy. Seminars in Hematology. 1998;35(4):291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebertz A, Arnett TR, Burnstock G. Regulation of bone resorption and formation by purines and pyrimidines. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;24(6):290–297. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Beavo JA, Bechtel PJ, Krebs EG. Comparison of adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases from rabbit skeletal and bovine heart muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1975;250(19):7795–7801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman G, Herman S, Schacht E. Poly(ethylene glycol)s with reactive endgroups. 2. Practical consideration for the preparation of protein-PEG conjugates. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 1996;11(2):135–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S, Foo C, Rossetti F, Textor M, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL, Boison D. Silk fibroin as an organic polymer for controlled drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2006;111(1–2):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan RL, Antle K, Collette AL, Huang YZ, Huang J, Moreau JE, Volloch V, Kaplan DL, Altman GH. In vitro degradation of silk fibroin. Biomaterials. 2005;26(17):3385–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]