Abstract

Capillary electrophoresis coupled with laser-induced fluorescence detection (CE-LIF) provides 15-s temporal resolution of amino acid levels in microdialysate, which, for the first time, allows almost real time measurement of changes during episodes of behavior. We trained Sprague-Dawley rats to self-administer either 10% ethanol-containing gelatin or non-alcoholic gelatin in a typical operant chamber. After rats reached stable daily levels of responding, microdialysis probes were inserted into nucleus accumbens and samples were collected before, during and after operant sessions with on-line analysis via CE-LIF. During the first 15 min of the operant session, there was a significant increase in taurine that correlated with the amount of ethanol consumed (R2 = 0.81) but no change in rats responding for plain gel. There were large, consistent increases in glycine in both the ethanol and plain gel groups which correlated with the amount of gel consumed. A smaller increase was observed in rats with free non-operant access to plain gel compared to the increase seen with the same amount of gel consumed under operant conditions. When rats were given a time out after each delivery of gel in the operant protocol, the greatest increase of glycine was obtained with the longest time out period. Thus, increases in glycine in nucleus accumbens appear to be related to anticipation of reinforcement.

Keywords: anticipation, ethanol, glycine, microdialysis, operant self-administration, taurine

One of the most valid preclinical models of alcoholism is that of self-administration, particularly operant procedures (the use of consequences to modify the occurrence and form of behavior), which allow quantification of the reinforcing effects of drugs (Poling and Bryceland 1979). These procedures allow the study of different contingencies for alcohol reward with good temporal resolution of self-administration behavior in a highly controlled environment and low day-to-day variability within both subject and condition (Sanchis-Segura and Spanagel 2006).

Many studies suggest that the mesolimbic dopaminergic (DA) system plays a very important role in the ethanol self-administration process. Operant self-administration of ethanol increases extracellular levels of DA in the nucleus accumbens (NAC) (Weiss et al. 1993; Doyon et al. 2003). Conversely, drugs such as naltrexone, which attenuate the rewarding properties of ethanol, attenuate ethanol-induced stimulation of DA activity in NAC (Gonzales and Weiss 1998). However, the precise role of DA in the rewarding properties of ethanol is far from clear. A recent study pointed out that a transient increase in DA in NAC may be related to the stimulus properties of ethanol presentation rather than its pharmacological or reinforcing actions (Doyon et al. 2004).

Alternative neurochemical mechanisms for regulation of operant ethanol self-administration have not been thoroughly explored. The few studies measuring amino acid changes following forced ethanol administration report increased basal levels of extracellular glutamate as measured by microdialysis (Dahchour and De Witte 2003). Taurine levels also are increased in a dose-dependent manner by ethanol (Dahchour et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2004) and this escalation is enhanced after repeated ethanol treatment (Dahchour and De Witte 2000). This finding suggests that taurine may be a possible neurobiological molecule involved in ethanol reinforcement. This hypothesis is supported by findings that acamprosate (a calcium homolog of taurine) and homotaurine (a taurine precursor) both modulate the mesolimbic DA system and decrease ethanol reinforcement processes (Olive et al. 2002; Cowen et al. 2005). However, no study has reported changes in taurine or other amino acids during operant ethanol self-administration.

Changes in neurotransmitter release are thought to occur over a short time period during most behavioral events. Thus, in vivo detection of neurotransmitters under these conditions should have a high temporal resolution. To date, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) and microdialysis sampling with HPLC have been used most often. FSCV provides good chemical selectivity as well as sub-second temporal resolution (Robinson et al. 2003). However, it is not able to determine basal concentrations or to detect DA changes for periods longer than 90 s (Heien et al. 2005). In contrast to FSCV, microdialysis sampling with HPLC can estimate basal concentrations and detect both DA and amino acid changes over longer times, but it requires longer sampling times, usually 5–20 min per sample. Each sample represents an average concentration during this period and so precludes detection of more rapid changes of extracellular chemicals associated with neurotransmission. A newer method, capillary electrophoresis (CE), possesses a high mass sensitivity (Zhou et al. 1995; Robert et al. 1998; Shou et al. 2006) and so requires only a very low volume of sample (≈20 nL), decreasing sampling time to 1 s. Coupled with an on-line separation time of about 14 s, this brings the sampling frequency within the range to allow monitoring of rapid changes that may correlate with behavioral episodes.

Ethanol in water is not extremely palatable, and many protocols in rodents require some form of deprivation and/or sucrose fading to establish high levels of intake. However, these are quite unlike the way that humans start to use ethanol. To better emulate this, we developed an ethanol-containing gelatin (10% ethanol, 10% Polycose®, 0.25% gelatin, wt/vol) that induces reliable and robust self-administration without food or water restriction (Rowland et al. 2005; Peris et al. 2007). Voluntary consumption of this ‘jello shot’ results in pharmacologically relevant concentrations of ethanol in brain (Peris et al. 2007) comparable to those previously reported after similar amounts of voluntary ethanol drinking (Nurmi et al. 1999).

In the present study, we used CE coupled with laser-induced fluorescence detection (CE-LIF), to provide for the first time, almost real time measurement of amino acid changes in microdialysate during operant responding for ethanol gel. This approach allows exploration of neural mechanisms underlying ethanol self-administration as well as those involved in positive reinforcement and anticipation of reward.

Materials and methods

Animals and housing

Male and female Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this study. Male rats used in Experiments 1 and 2 were approximately 6 months of age and weighed 485 ± 11 g at the beginning of the study. Female rats used in Experiments 2 and 3 were approximately 2 months of age and weighed 200 ± 8 g at the beginning of the study. Body weight was recorded weekly. All rats were individually housed in a vivarium with a 12 : 12 light : dark cycle (lights off at 09:00) and an ambient temperature maintained at 23 ± 2°C. Rat use was approved by the IACUC and was consistent with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Purina 5001 Rodent Chow and tap water was available ad libitum at all times except during daily operant sessions.

Behavioral apparatus

Each chamber consisted of a typical operant chamber with accessories located inside a sound attenuating isolation cubicle (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA). Operant chambers measured approximately 50.8 cm W × 25.4 cm D × 30.5 cm H with a grid non-shock floor and solid walls. Two levers protruded through one wall of the chamber, placed symmetrically on either side of an optical lickometer. A standard drinking spout was affixed into the lickometer, such that the spout protruded into the chamber. A 20 mL syringe filled with 10% gelatin was placed into a syringe pump inside the isolation cubicle, outside of the test cage before each session. The syringe was connected using parafilm to tubing with an inside diameter of 3.2 mm and an outside diameter of 4.8 mm. The tubing led into the drinking spout which was cleaned daily with hot water. Syringes containing gel were refrigerated between daily sessions. Graphic State 5.2 operating software (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA) was used to control gel delivery and collect behavioral data.

Reinforcers

Two types of gel reinforcement were used. The ethanol gel (1.03 kcal/g) was made with 10% ethanol (wt/vol), 10% Polycose® (wt/vol) (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and 0.25% gelatin (wt/vol) (Knox brand, Kraft Foods, Northfield, IL, USA) in water. Polycose is an oligosaccharide mixture (~4 kcal/g) that is sweet to rats. The second reinforcer was control (plain) gel (0.45 kcal/g) not containing alcohol, and was made from gelatin and Polycose at the above concentrations. The standard amount of gel delivered per reinforcement was 0.3 mL over 10 s.

Experimental procedures

Experiment 1

Acclimation to control gel in home cage

Fourteen male rats were given free access to a 50 mL glass jar of control gel, containing polycose but no ethanol, hung from a metal stirrup in their home cage. The gel was available for 24 h for the first 2 days of exposure, then for 6 h for 2 days, then 3 h for 2 days and finally for 1 h per day for approximately 2 weeks as described earlier (Peris et al. 2007).

Gelatin administration in the operant chamber

Shaping

When 1 h free access consumption of the control gel stabilized (Peris et al. 2007), rats were placed in the operant chamber for a 10 min shaping session. During shaping, gel reinforcements were delivered as the rats made successive approximations towards pressing the lever for a total of 3–5 reinforcements. This shaping session was immediately followed by a 30 min session in which gel delivery was contingent an FR1 schedule (one lever press yielded a reinforcement). A visual cue light was illuminated above the left lever at all times. Another visual cue, the house light, was illuminated to signal gelatin delivery and was terminated at the end of the 10 s gel delivery.

Fixed ratio (FR) schedule

After 3 days of shaping followed by FR1 sessions, rats were tested daily in 30 min FR1 sessions for 30 days with only control gel reinforcement. They were then divided into two groups based on their performance under the FR1 schedule. The ethanol group (n = 9) then only received reinforcements of 10% ethanol-containing gelatin and the control group (n = 5) continued responding for the non-alcoholic control gel. At the same time, the reinforcement requirement was increased to FR5, i.e., five presses on the left lever were required for each reinforcement. During this training, a time out was introduced after each reinforcement which was gradually incremented (by 5 s per day) from 5 to 120 s. Session length was also gradually increased to 50 min to allow for the same total number of reinforcements for each rat to remain stable. There was little spillage of the gel and this mostly occurred during initial training sessions. Any spillage that occurred was removed from the spout and weighed to the nearest 0.01 g and subtracted from the daily total. All operant sessions were run during the light period at approximately the same time each day.

Experiment 2

Several procedures were used to investigate the possibility that the effects observed in Experiment 1 might be due to the operant task itself. We thus examined non-operant, free access to various non-alcoholic commodities in a standard home cage (40 cm × 40 cm × 30 cm high).

Gel administration in home cage

Ten male rats and 6 female rats received free access to the control gelatin in the home cage. The procedure was otherwise the same as Experiment 1.

Free access to moist chow or sugar fat whip in home cage

Six male rats received free access to moist chow (equal weights chow and water) for 1 h after overnight food deprivation on at least three occasions before microdialysis surgery. Another 6 male rats received free access to sugar fat whip (shortening : sugar = 2:1) for 24 h (chow was also available) for the first 2 days of exposure, then for 6 h for 2 days, then 3 h for 2 days and finally for 1 h for about 3–7 days before microdialysis surgery.

Experiment 3

Ten female rats received free access to control gel in the home cage. The procedure was the same as Experiment 1. After 3 days, shaping followed by FR1 sessions, rats received daily 30 min FR1 sessions for 30 days. At this point, the female rats were divided into two groups based on their performance under the FR1 schedule. The first group (n = 5) were moved to 50-min FR5 session with no time out after reinforcement, and the second group (n = 5) were moved to 50-min FR5 session with a gradually increased time out (10 s/day) after each delivery reaching a maximum 5-min time out.

Surgery and microdialysis experiments

Each rat was anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus for surgical implantation of a guide cannula. The guide cannula (21 gauge; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) was positioned to end within 1 mm above the left side of NAC or hippocampus using the following flat skull coordinates from bregma: +1.8 anteroposterior, +1.3 lateral, −6.2 dorsoventral for NAC; −5.0 anteroposterior, +5.0 lateral, −6.2 dorsoventral for hippocampus. The guide cannula was secured to the skull with dental cement anchored by three stainless steel screws. After surgery, each rat was individually housed and allowed to recover for at least 2 days before the daily ethanol gel or control gel operant session was restarted. Rats then resumed operant sessions but were now tethered to a swivel in the top of the operant chamber by a spring attached to a clip embedded in the dental cement on their skulls. Habituation to the tethering procedure continued for 3–7 daily sessions.

Microdialysis probes (o.d. 270 µm; active length 2 mm; cellulose membrane, 13 000 molecular weight cut-off) were constructed by the method of Pettit and Justice (1989). The probe was perfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (145 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 0.45 mM monobasic phosphate, 1.55 mM dibasic phosphate, pH 7.0–7.4) at 1 µL/min. A calibration curve was generated for each probe by collecting a total of 175 samples after placing the tip of the dialysis probe in seven different concentrations (0.63–20 µM) of a 37°C, well-stirred standard solution containing glutamate, aspartate, GABA, taurine, serine, glutamine, and glycine. The mean relative fluorescence of these samples was converted to concentration by plotting peak height versus standard concentration. Thus, extraction fraction in brain dialysate samples was automatically accounted for except for possible minor differences in diffusion based on analytes in solution versus in a matrix.

At this point, each rat was moved into the dialysis cage which was either an operant chamber without the sound attenuating chamber or a home cage provided with bedding, water bottle and food. The dialysis probe was inserted into NAC or hippocampus without anesthesia 2 h before the start of the 50 min operant session or 1 h free access period. The levels of amino acids were analyzed on-line every 15 s during the 2 h baseline period, the 50-min operant session or 1 h gel presentation, and for 1–2 h additionally.

CE-LIF

Amino acids were measured utilizing the procedure established by Lada and Kennedy (1996) and refined by Bowser and Kennedy (2001) and Smith et al. (2004). Briefly, analytes in the dialysate containing primary amine moieties were derivatized on-line by mixing dialysate flow with a 1 µL/min stream of o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) derivatization solution (10 mM OPA, 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 36 mM borate, 0.81 mM HPBCD, 10% MeOH (vol/vol), pH 10.5), with a reaction time of approximately 30 s. The reaction time does not limit the temporal resolution of the measurement, although there is a 4–5 min delay between a sample leaving the dialysis probe and its detection by the CE system because of the volume of the transfer tubing. The delay time was quantified for each experiment during calibration of the instrument. Samples of the dialysate were injected onto the capillary (separation buffer = 40 mM borate, 0.9 mM HPBCD) using a flow-gate interface as described previously (Lada and Kennedy 1996; Bowser and Kennedy 2001; Smith et al. 2004). The OPA labeled analytes were detected using LIF in a sheath-flow detector cell. Fluorescence was excited using the 351 nm line (20 mW total UV) of an argon-ion laser (Enterprise II 622; Coherent Laser Group, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Emission was filtered and collected at 90° from the incident beam on a photomultiplier tube (R9220; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Current from the photomultiplier tube was amplified and sampled with the same software and hardware used for controlling the injections.

Data analysis and histology

About 300 electropherogram files, each containing over 11 000 data points, were collected each hour using the CE-LIF instrument. The calculations of peak heights in these files were performed by ‘Cutter’, a Lab-View-constructed VI in which electropherograms are batch post-processed (Shackman et al. 2004). The first 20 or more samples collected for each hour (prior to operant sessions) were used to calculate a baseline. Subsequent data were expressed as a percent of this baseline and calculated across animals as the mean ± SEM.

As an internal standard, we used a peak that is comprised of all the non-charged analytes that are labeled by OPA. This peak (which we will refer to as the OPA peak) has been shown to be very consistent from 1 to 6 h after probe implantation since the only factor which might alter its size is the injection efficiency of the flow gate. Thus, it is a good indicator of instrument variability and can be used as a control for the levels of the amino acids. In some cases, we present the OPA data as a reference peak and in some cases, in order to reduce sample to sample variability caused by the instrument, we present the data as a ratio of the analyte of interest to the OPA peak (e.g., Fig. 3).

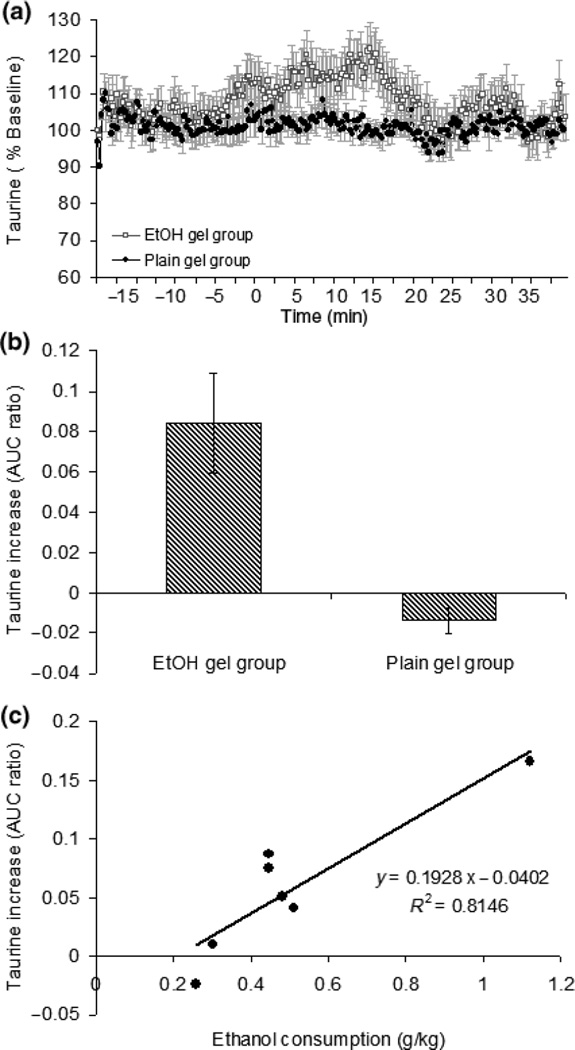

Fig. 3.

Taurine levels during the 50-min FR5 session with 2 min time out . Panel a: during the first 15 min, there was a significant increase in taurine levels (N = 7). The data are shown as % baseline of taurine divided by the % baseline of the OPA peak (which stayed at 100% throughout the session – see Fig. 4) and lined up by the first reinforcement for each rat (indicated by the arrow). The basal level of taurine was 2.9 ± 0.02 µM for ethanol and 2.64 ± 0.09 µM for plain gel. Panel b: for the rats consuming ethanol higher than 0.4 g/kg (N = 5), there was a significant increase in taurine compared to no change in the plain gel group [F(1,9) = 18.2, p < 0.05]. The data are shown as the AUC ratio. Panel c: there was a significant correlation between the taurine increase and amount of ethanol consumed for each individual rat (R2 = 0.81, p < 0.05, N = 7).

We also calculated the area under the curve for each time– response curve for every analyte of interest. To summarize these data, D area under the curve (D AUC) was calculated for each amino acid by subtracting the OPA AUC from the amino acid AUC. The AUC ratio for each amino acid was calculated by dividing amino acid Δ AUC by the OPA Δ AUC.

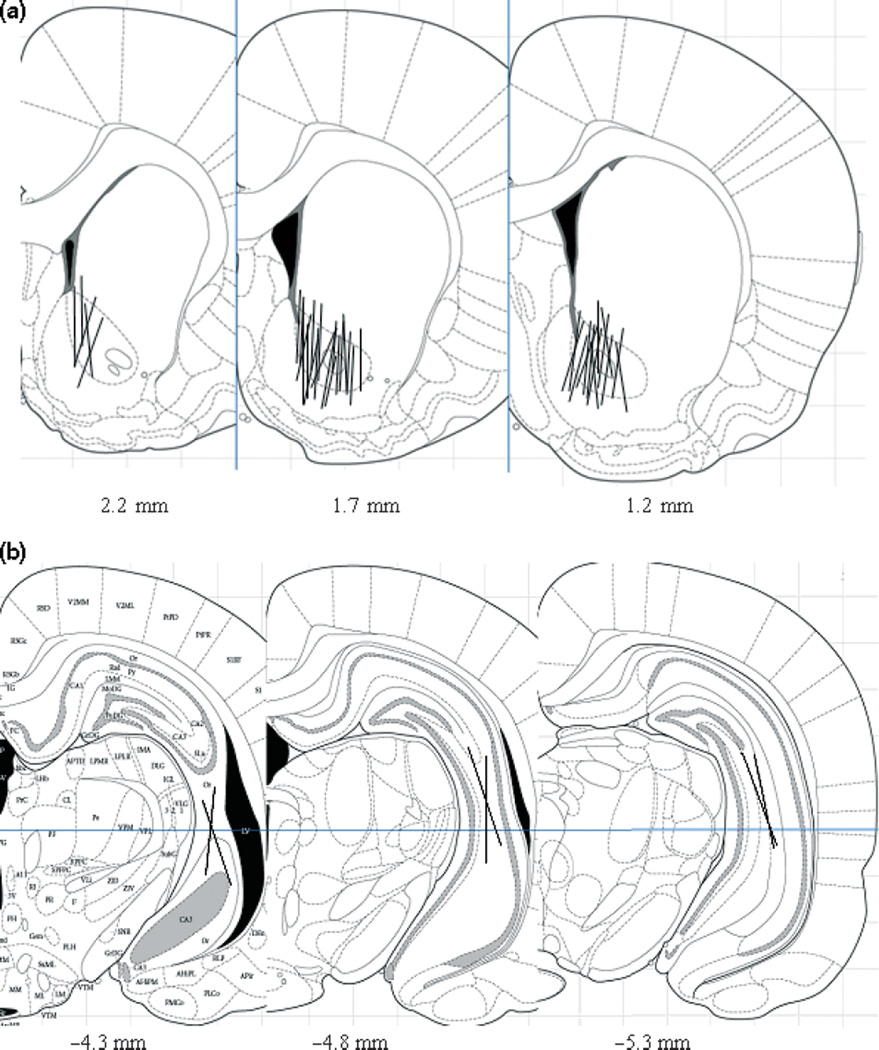

Data were analyzed using ANOVA or paired T-test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used or all statistical analyses. At the end of each experiment, the brains were removed and sectioned to verify the correct position of the probe. Only the data from rats with accurate probe placement were included in data analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Coronal sections showing microdialysis probe placement within NAC and hippocampus for all animals. Lines indicate the active dialysis regions. Numbers below the figure represent the position of the slice relative to Bregma. The figure was adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2005).

Results

Experiment 1

Gelatin consumption

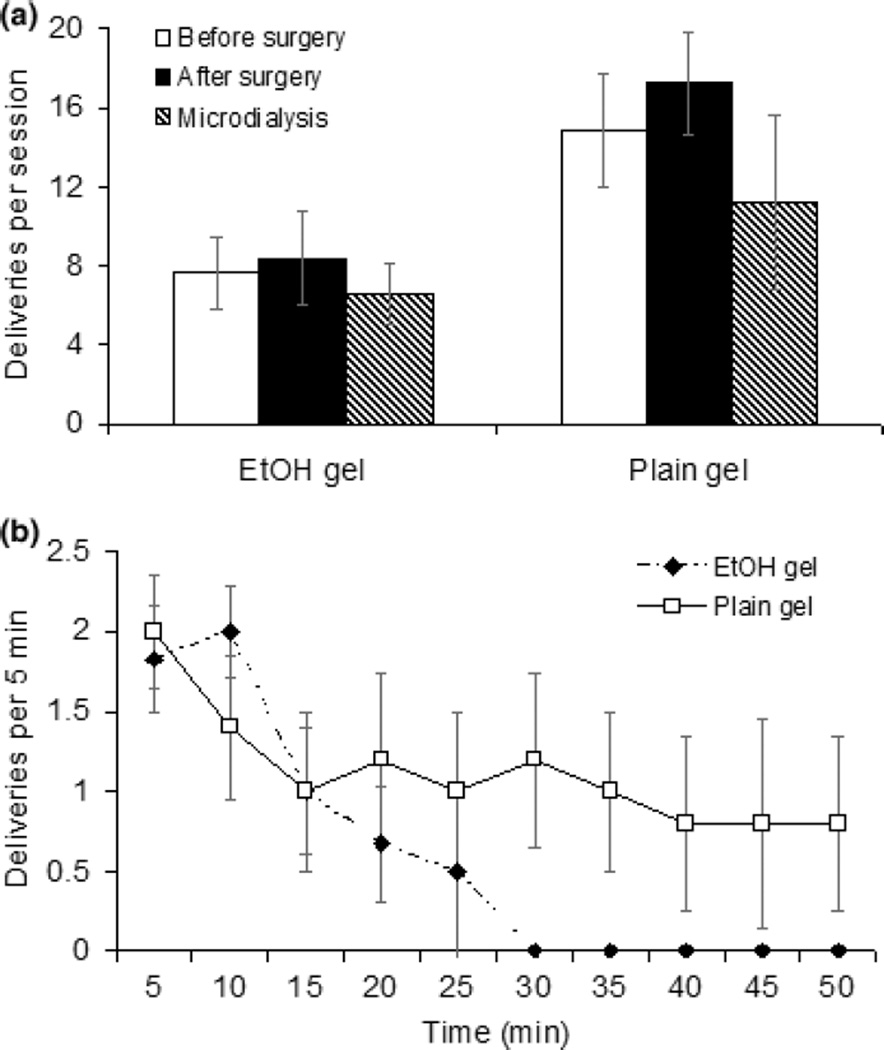

The number of ethanol gel and plain gel reinforcements obtained before surgery, after surgery, and on the dialysis day are shown in Fig. 2. Rats took more reinforcements with plain gel than ethanol gel mainly because rats responded for plain gel throughout the session while those rats consuming ethanol gel stopped after 10–15 min (Fig. 2b). These observations were supported by a significant time X treatment X gel delivery interaction [F(10,100) = 21.7, p < 0.001].

Fig. 2.

Gelatin consumption for FR5 schedule with a 2 min time out. Panel a: comparison of the number of deliveries before surgery, after surgery and on the day of the microdialysis experiment. Responding for ethanol or plain gel was not disrupted by either surgery or micro-dialysis. Deliveries of plain gel were significantly higher than ethanol gel at all times. Panel b: the number of ethanol and plain gel deliveries per 5 min period during the 50-min FR5 microdialysis session. There were fewer deliveries in the ethanol group during the last 30 min of the session [F(5,50) = 16.04, p < 0.0001]. Each data point is the average of the number of deliveries per 5 min period with N = 7 for the ethanol group and N = 5 for the plain gel group.

Effect of operant ethanol self-administration on taurine release in NAC

There was a significant increase in taurine levels in NAC during 50 min of operant responding for ethanol gelatin compared with no change in the plain gel group (Fig. 3a and c). This observation was supported by a significant ethanol main effect [F(1,9)=18.2, p < 0.05]. For the rats consuming higher than 0.4 g/kg ethanol (N = 5), the average increase in taurine was 8.4 ± 2.5%. In addition, the taurine increase was well correlated with ethanol dose (R2 = 0.81) with a maximum increase of 16.7% at an intake of 1.1 g/kg ethanol (Fig. 3b).

Effect of gelatin consumption on the glycine and serine levels in NAC during operant self-administration

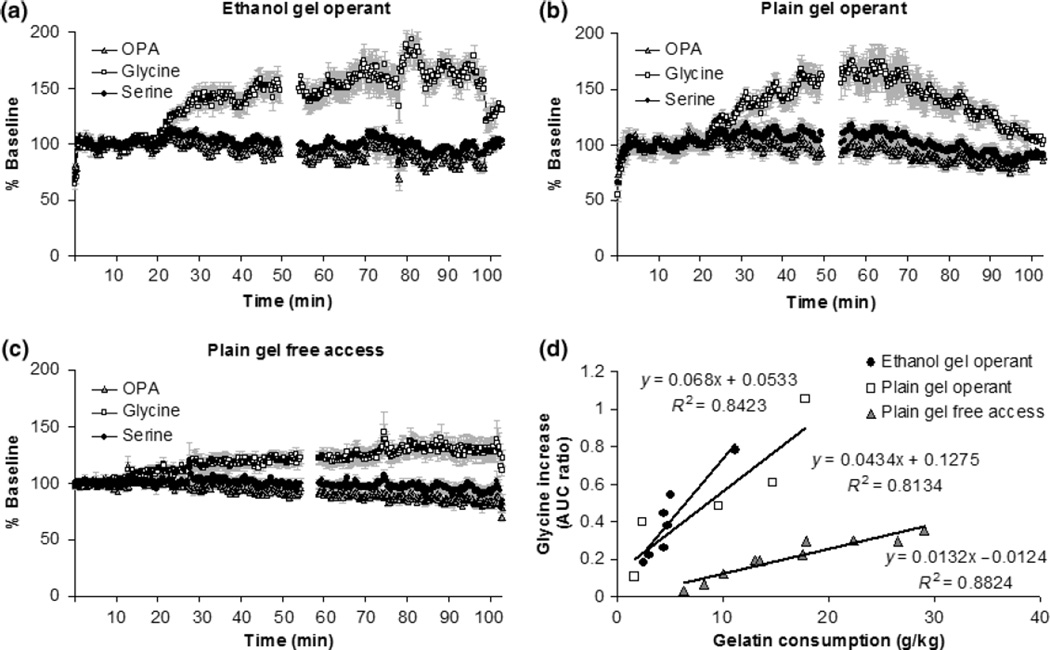

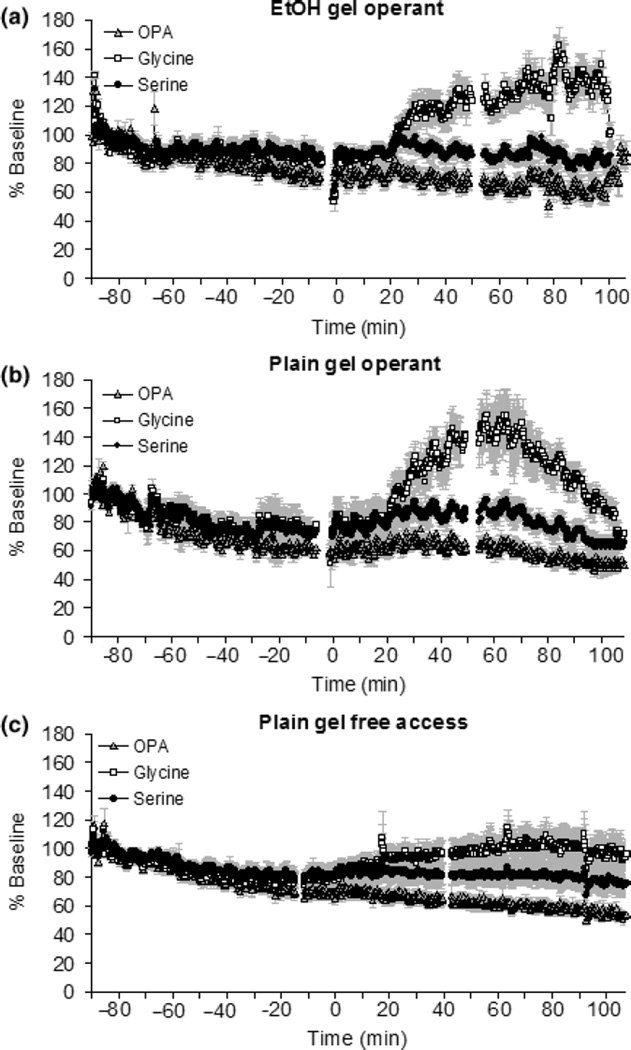

There were large, consistent increases in glycine and small but consistent increases in serine in both the ethanol and plain gel groups during operant responding (Fig. 4). This observation was supported by significant time X neurotransmitter interactions [F(1841, 12929) = 1621, p < 0.001 for ethanol gel operant; F(1841,12929) = 1718, p < 0.001 for plain gel operant; F(1841,12929) = 439, p < 0.001 for plain gel free access]. Glycine increases correlated significantly with the amount of gelatin consumption in both groups (Fig. 4d). There were no changes in either GABA or glutamate (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

The levels of glycine and serine during and 1 h following operant responding or free access to gel reinforcement. The levels of the OPA-labeled neutral peak are included in each panel for comparison. Panel a: levels of glycine and serine during and after operant ethanol gel self-administration (N = 7). The basal levels of glycine and serine were 0.57 ± 0.07 µM and 10.68 ± 0.15 µM, respectively. Panel b: levels of glycine and serine during and after operant plain gel self-administration (N = 5). The basal levels of glycine and serine were 0.71 ± 0.1 µM and 13.51 ± 0.23 µM, respectively. Panel c: levels of glycine and serine during and after free access plain gel presentation and 1 h following the session (N = 10). The basal levels of glycine and serine were 0.67 ± 0.04 µM and 11.15 ± 0.25 µM, respectively. The data in panels a–c are shown as % baseline. Panel d: glycine increases were significantly correlated with gelatin consumption in all groups (R2 = 0.81, p < 0.05 in operant conditioning plain gel group, R2 = 0.84, p < 0.05 in operant conditioning EtOH group, R2 = 0.88, p < 0.05 in free access plain gel group). The data are shown as the AUC ratio.

Experiment 2

In order to determine whether the gel-induced increase in glycine is due to gelatin exposure or operant responding for gelatin, we also measured the change of amino acid levels during free access to plain gel in the home cage. The levels of glycine and serine increased in NAC during free access self-administration (Fig. 4c). The glycine increases during free access were also significantly correlated with gelatin consumption (Fig. 4d); however, the slope of this relationship in the free access condition was much less steep than in the operant condition. In addition, there were small but significant increases of glycine and serine level about 10 min before the start of the operant session (Fig. 5a and b) but no change in glycine or serine levels before access to plain gel (Fig. 5c). These results was supported by significant time X neurotransmitter interactions [F(2208,15504) = 2054, p < 0.001 for ethanol gel operant; F(2208,15504) = 2198, p < 0.001 for plain gel operant; F(2208,15504) = 789, p < 0.001 for plain gel free access].

Fig. 5.

The levels of glycine and serine before, during and after operant responding or free access. The results are showed as % baseline using the data as the baseline right after implantation of probe. There are small increases of glycine and serine levels about 10 min before the session started for both operant plain gel and ethanol groups compared to very little change in the free access plain gel group (panel a, the operant ethanol gel group; panel b, the operant plain gel group; panel c, the free access plain gel group).

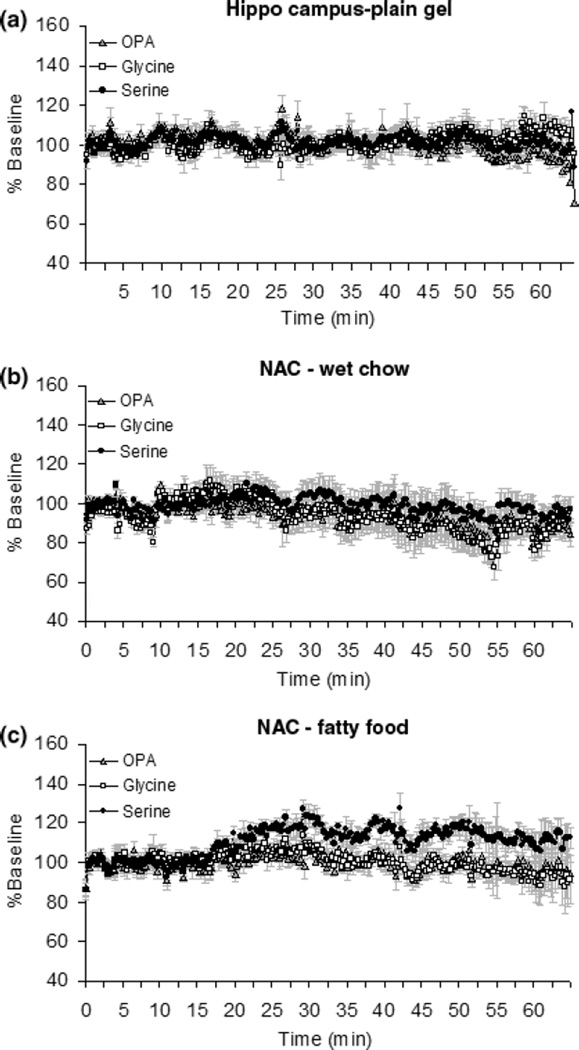

Effect of gelatin consumption on the glycine and serine levels in hippocampus”

To determine if the increase in glycine is specific to the NAC, we repeated the plain gel free access experiment with the probe location in hippocampus. There was no change in glycine or serine in hippocampus during free access plain gelatin consumption (Figs 6a and 7). The observation was supported by no time X neurotransmitter interaction.

Fig. 6.

The levels of glycine and serine in the hippocampus during free access plain gelatin presentation, and in the NAc during moist chow and sugar fat whip intake. Panel a: levels of glycine and serine in the hippocampus during free access plain gelatin presentation. The basal levels of glycine and serine 1.5 h after implantation of probe were 0.62 ± 0.07 µM and 12.04 ± 0.21 µM, respectively. Panel b: levels of glycine and serine in the NAc during moist chow intake. The basal levels of glycine and serine 1.5 h after implantation of probe were 0.70 ± 0.10 µM and 11.48 ± 0.13 µM, respectively. Panel c: levels of glycine and serine in the NAc during sugar fat whip intake. The basal levels of glycine and serine 1.5 h after implantation of probe were 0.72 ± 0.13 µM and 10.48 ± 0.29 µM, respectively. All data are shown as % baseline.

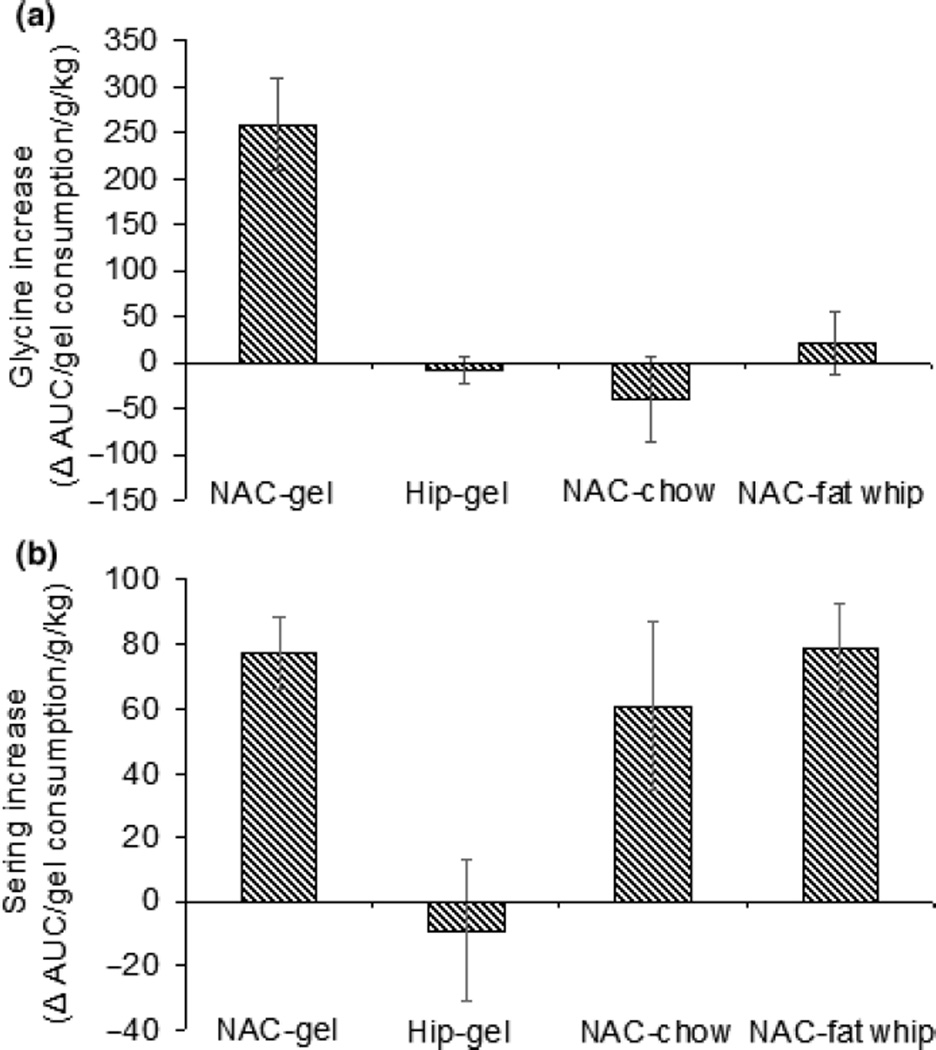

Fig. 7.

The levels of glycine and serine in the hippocampus and NAC during free access plain gelatin presentation and in the NAC during moist chow and sugar fat whip intake. Panel a: levels of glycine in the hippocampus and NAC during free access plain gelatin presentation; in the NAC during moist chow and sugar fat whip intake. The level of glycine only increased during gelatin consumption when the probe was in the NAC [F(3,20) = 30.4, p < 0.05]. The data are shown as the AUC of glycine divided by the amount of gelatin consumed per body weight. Panel b: levels of serine in the hippocampus and NAC during free access plain gelatin presentation; in the NAC during moist chow and sugar fat whip intake. The increases of serine level only increased during gelatin consumption when the probe in NAC [F(3,20) = 14.2, p < 0.05]. The data were shown as the AUC of serine divided by the amount of gelatin consumed and body weight.

Effect of moist chow and sugar fat whip on glycine and serine levels in NAC

In order to determine whether glycine was increased by other food commodities, we investigated the levels of glycine and serine during intake of moist chow or sugar fat whip. There was no change in the extracellular concentration of glycine in NAC during either wet chow (Figs 6b and 7a) or sugar fat whip (Figs 6c and 7a) intake. There was no time X neurotransmitter interaction for OPA and glycine. Slight increases in levels of serine were observed under both conditions (Figs 6b, c and 7b). One-way ANOVAs revealed a significant effect of gel intake on glycine release [F(2, 15) = 9.09, p < 0.005]. A significant effect of brain region on glycine [F(1,10) = 37.41, p < 0.0001] and serine release [F(1, 10) = 6.94, p < 0.05] has been supported by the result of T-test. There was no effect of moist chow and sugar fat whip on taurine release in NAC (data not shown).

At this point, we chose to use female rats in all subsequent operant experiments, since they have more consistent and slightly higher self-administration data (Eriksson 1968). Therefore, we measured whether there is a sex difference in glycine and serine levels in NAC during free access presentation of plain gelatin. Both sexes ate similar amounts of gel (21.9 ± 6.5 g/kg for female; 16.5 ± 2.5g/kg for male) and had similar increases in glycine (31.2 ± 15.2% for females; 20.6 ± 3.6% for males) and serine (6.6 ± 2.5% for females; 4.8 ± 1.4% for males).

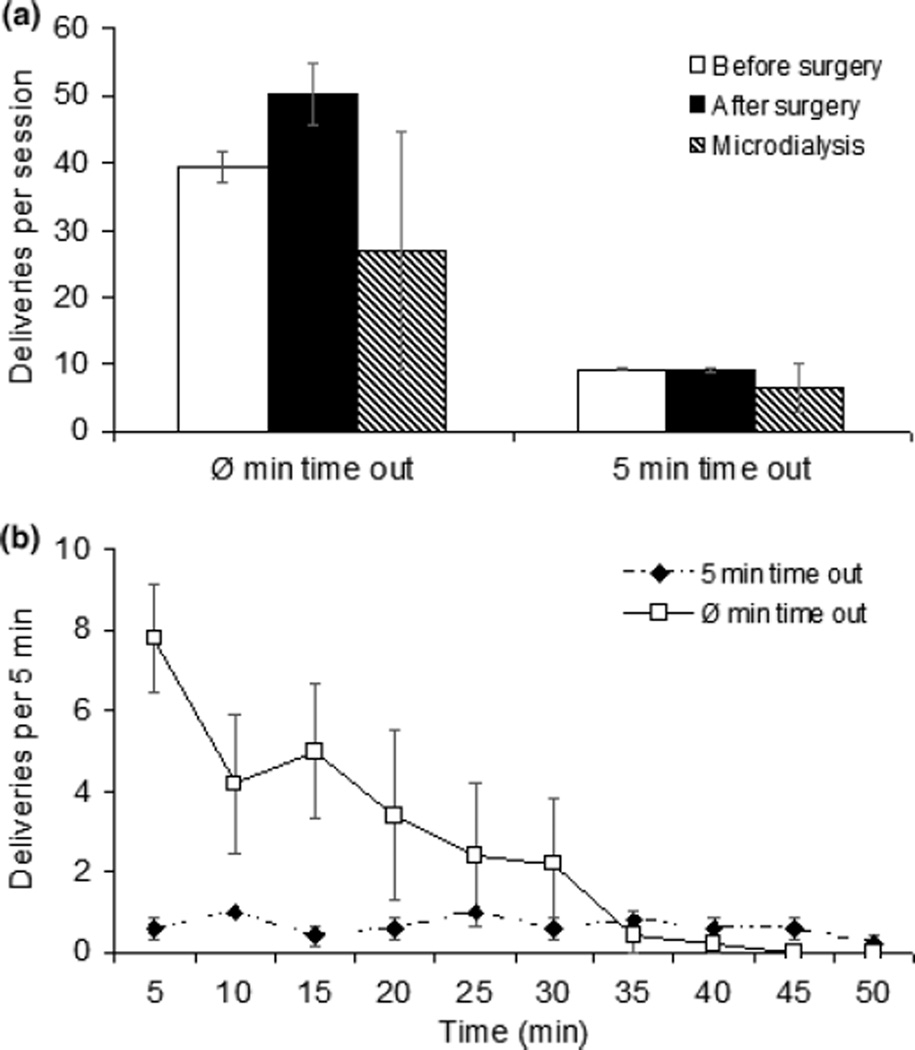

Experiment 3

Effect of time out periods during operant self-administration of plain gel

We next tested whether the increase of glycine in NAC may be involved in anticipation of reward. Therefore, we trained female rats to respond for plain gel under an FR5 schedule either with 0 or 5 min time-outs after each delivery. As before, responding for plain gel was not disrupted by either surgery or microdialysis sampling. Deliveries in the no time-out group were significantly higher than the 5 min time out group both before and after surgery (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Gelatin consumption for no time out and 5 min time out groups. Panel a: comparison of delivery number before surgery, after surgery and on the microdialysis day. Rat responding for plain gel were not disrupted by either surgery or microdialysis. Deliveries in the no time out group were significant higher than in the 5 min time out group both before and after surgery. Panel b: number of deliveries per 5 min period during the 50-min FR5 session during microdialysis for no time out and 5 min time out groups. (N = 5 for no time out, N = 5 for 5 min time out).

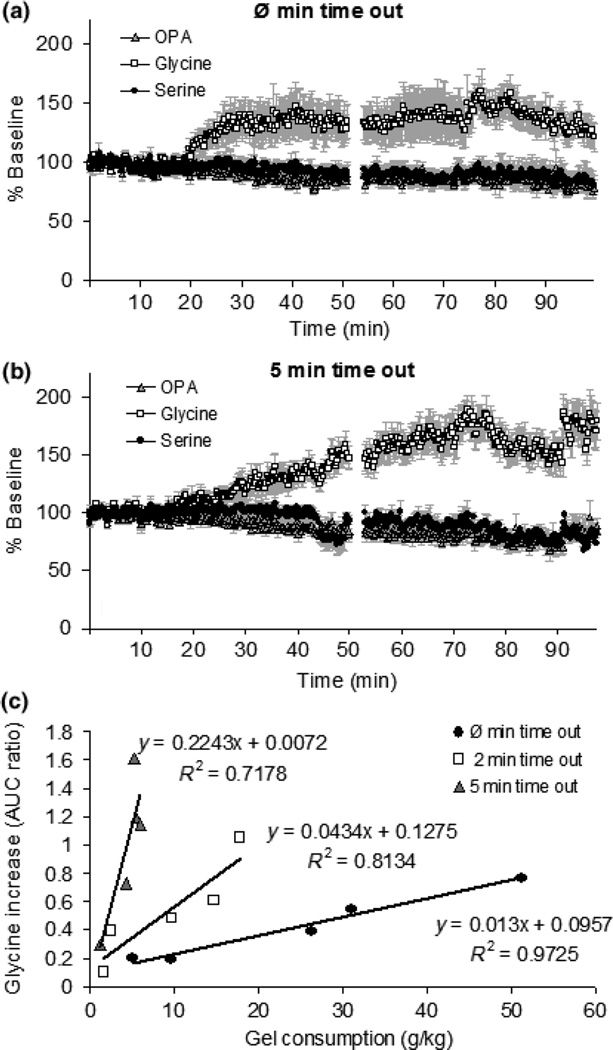

The levels of glycine were increased less in the no time out group (Fig. 9a) compared to the 5-min time out group (Fig. 9b). Glycine increases were significantly correlated with gel consumption in both groups but with a much steeper slope in the 5-min time out group (Fig. 9c).

Fig. 9.

The levels of glycine and serine during, and 1 h following, operant responding under an FR5 schedule with 0 min or 5 min time out between reinforcements. Panel a: levels of glycine and serine during operant responding under FR5 schedule with no time out (N = 5). The basal levels of glycine and serine 1.5 h after implantation of probe were 0.64 ± 0.17 µM and 11.31 ± 0.17 µM, respectively. Panel b: levels of glycine and serine during operant responding under FR5 with 5 min time out (N = 5). The data in panels a and b are shown as % baseline. The basal levels of glycine and serine 1.5 h after implantation of probe were 0.52 ± 0.06 µM and 10.59 ± 0.26 µM, respectively. Panel c: glycine increases were significantly correlated with gelatin consumption in all groups but much larger increases were seen in the 5 min time out group even though they ate much less gel (R2 = 0.72, p < 0.05 in 5 min time out group, R2 = 0.97, p < 0.05 in no time out group). The data are shown as the AUC ratio.

In addition, substantial increases of glycine and serine levels were also observed in both groups about 30 min before the session started (Supplementary material Fig. S1). The observation was supported by two ANOVA statistic results that there was a significant neurotransmitter effect over all [F(5, 29) = 6.25, p < 0.05].

Discussion

The effect of operant ethanol self-administration on taurine levels in NAC

The present findings are the first to show that extracellular taurine levels increase in NAC during operant ethanol self-administration and that the magnitude of the increase is correlated with the amount of ethanol consumed. Several previous studies have shown that taurine release increases in NAC following IP ethanol injection in a dose-dependent manner (Dahchour and De Witte 2000a; Smith et al. 2004). Our results support and extend these observations by measuring taurine release during operant ethanol self-administration which, in Sprague-Dawley rats, results in fairly low brain ethanol levels. We found statistically reliable, though small (8.4 ± 2.5%) increases in taurine in rats that consumed more than 0.5 g/kg ethanol. When 0.5 g/kg ethanol is, given IP, taurine levels in NAC increase by 20% for about 10 min (Smith et al. 2004). There is a similar two-fold difference in the brain ethanol levels found after self-administration of 0.44 ± 0.06 g/kg ethanol compared to intra-gastric gavage of 0.5 g/kg ethanol (Peris et al. 2007). In addition, the rats in the present study were self-administering ethanol under an FR5 reinforcement schedule with 2-min time out after each delivery schedule. This schedule ensures that ethanol intake is spread over ~20 min (Fig. 2). Thus, it is not surprising that any alterations in taurine levels caused by ethanol concentrations rising in the brain would be more subtle under these conditions and would require a very sensitive measure of small changes in amino acid levels. Our studies provide the first evidence that the level of taurine increases in NAC during operant ethanol self-administration, probably because of the high temporal resolution of the CE-LIF technique.

Taurine is a non-essential sulfur-containing amino acid in the brain, present both in neurons and glial cells (Huxtable 1992). It has many biological roles including neurotransmission and osmoregulation (Wright et al. 1986; Huxtable 1992). The neural mechanism of the increase in taurine release following ethanol administration is not fully understood. Several previous studies suggested ethanol-induced taurine efflux may be due to neuronal depolarization (Smith et al. 2004), while other studies have indicated that ethanol-induced taurine efflux may be primarily due to osmoregulation (Quertemont et al. 2003).

In contrast to taurine, we found no effect on glutamate or GABA during operant ethanol self-administration. A previous study suggested that an increased level of extracellular glutamate is a key neurochemical feature associated with ethanol withdrawal (Melendez et al. 2005). In the current study, Sprague-Dawley rats had an average daily ethanol consumption of 0.67 ± 0.01 g/kg, which is not high enough to develop withdrawal symptoms in the hours following ethanol exposure. Only one previous study described an increase in NAC extracellular GABA levels during alcohol consumption (Szumlinski et al. 2007). The discrepancy in findings with this early study may be related to alcohol dose (0.67 g/kg vs. 1.5–1.6 g/kg) and/or the species used (Sprague–Dawley rat vs. C57BL/6J mouse).

The relationship between the increase of glycine and anticipation

A large and constant increase in glycine levels in NAC was observed during both plain gel and ethanol gel operant responding periods. Gelatin is high in the non-essential amino acids glycine and proline, however, it does not appear that this is the cause of the increase in glycine seen in the NAC after gel consumption. First, the increase in glycine was greatest under operant conditions even though much more gel was consumed under free access conditions. This increase did not occur in hippocampus indicating that it is not due to an overall increase in brain glycine levels that might reflect high glycine content of gelatin. Normally, people consume approximately 0.023 g/kg of glycine per day and this dietary glycine does not influence brain glycine level (Lehninger 1982). In contrast to humans, our rats consumed much smaller amount of glycine (0.016 g/kg in FR5; 0.004 g/kg in FR5-2 min time out; 0.003 g/kg in FR5-5 min time out; 0.011 g/kg during free access). On the other hand, some studies have shown that peripherally administered glycine may pass the blood–brain barrier and functionally elevate brain glycine levels when administered in sufficient quantity (Toth and Lajtha 1986; Toth and Weiss 1986; Peterson 1994; D’Souza et al. 1995). However, the doses of glycine used in these previous papers are at least 50–200 times higher than the amount of glycine that our rats consumed. Therefore, the amount of glycine consumed by our rats is not high enough to elevate the level of glycine in the brain.

Interestingly, there was also a small increase in glycine about 10 min before the start of the operant session for both ethanol and plain gel groups but not prior to free access sessions. In the operant experiments, rats were trained for 1 month to wait in the operant chambers for exactly 2 h before the session started. Thus, environmental and temporal cues were present for these rats concerning the impending gel reinforcement. Since the free access experiments were performed in cages that were identical to the home cage, these cues were not present. Finally, the longer the rat had to wait between barpressing episodes during a session, the greater the subsequent increase in glycine in the NAC, regardless of the fact that fewer reinforcements were given under these conditions. Together, these findings indicate that an increase in glycine in NAC may be more involved with anticipation of reward rather than reward itself.

There were no changes in glycine levels after presentation of rat chow or other palatable food. One previous study suggests that glycine levels decrease 30% in NAC during normal food consumption (Saul’skaya et al. 2001). Our data showed that there was no change in glycine level during normal chow intake. The discrepancy in the findings with the earlier study may relate to the different food administration before microdialysis. Our rats were food deprived for the 18 h prior to microdialysis to ensure that they consumed the food upon presentation. In the earlier study, rats received regular food administration which may suggest that food deprivation blocked or compensated for the food intake-induced reduction of glycine level in NAC. In addition, the level of glycine also did not change in the NAC during consumption of sugar fat whip intake, which would have been expected if glycine increased purely as a result of consumption of highly palatable food. In other studies, we have found that rats consume more sugar fat whip than gelatin, further suggesting that the increase in glycine in NAC was not caused by intake of any highly palatable food.

Neurotransmission has been considered as the common release pool of glycine. However, there is some evidence indicating that glycine may also be released from non-neuronal sources. Previous studies demonstrated that there is a difference in the energetic coupling of the two glycine transporters (GlyT1 and GlyT2). GlyT2a has a kinetic constraint for reverse transport that limits glycine release but GlyT1b does not (Roux and Supplisson 2000). Therefore, it is possible that glycine releases through reverse transport from astrocytes. In addition, it has been reported that glutamate activates AMPA receptors in glial cells which may produce a depolarization and increase the concentration of Na+ inside of glial. This could be sufficient to reverse GlyT1b transport, thus increasing the extracellular concentration of glycine (Attwell et al. 1993). For the current study, the elevated glycine in NAC because of anticipation needs to be further characterized to determine the exact source.

Recent work demonstrates that glycine and strychnine alter extracellular DA levels in the NAC, probably via glycine receptor stimulation and blockade, respectively (Molander et al. 2005). The taurine-induced DA increase in the NAC is completely blocked by perfusion of the competitive glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (Ericson et al. 2006). Therefore, it suggested that accumbal glycine receptors may be an access point for brain reward system. However, the present findings are the first to report that the glycine system plays a role in anticipation of reward.

Our study, for the first time, showed the real time measurement of changes in amino acid levels during operant responding by using CE-LIF coupled with on line microdialysis. Our data support previous findings that ethanol increases the extracellular concentration of taurine in NAC, even with the very low brain ethanol concentrations achieved during operant ethanol self-administration. In addition, our novel findings concerning alterations of glycine in NAC in response to different reinforcement schedules strongly suggest this neurotransmission as being involved in anticipation of reward.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs Robert T. Kennedy, Christopher J. Watson, Cheryl Vaughan and Britney Jowers for technical support. This work was supported by PHS grant AA014708.

Abbreviations used

- AUC

area under the curve

- CE

capillary electrophoresis

- CE-LIF

Capillary electrophoresis coupled with laser-induced fluorescence detection

- DA

dopamine

- FSCV

fast-scan cyclic voltammetry

- NAC

nucleus accumbens

- OPA

o-phthalaldehyde

Footnotes

The following supplementary material is available for this article:

Fig. S1 The levels of glycine and serine using the baseline right after implantation of probe.

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.005346.x (This link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Attwell D, Barbour B, Szatkowski M. Nonvesicular release of neurotransmitter. Neuron. 1993;11:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90145-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser MT, Kennedy RT. In vivo monitoring of amine neurotransmitters using microdialysis with on-line capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:3668–3676. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200109)22:17<3668::AID-ELPS3668>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen MS, Adams C, Kraehenbuehl T, Vengeliene V, Lawrence AJ. The acute anti-craving effect of acamprosate in alcohol-preferring rats is associated with modulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system. Addict. Biol. 2005;10:233–242. doi: 10.1080/13556210500223132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza DC, Chamey D, Krystal J. Glycine site agonists of the NMDA receptor: a review. CNS Drug Rev. 1995;1:227–260. [Google Scholar]

- Dahchour A, De Witte P. Ethanol and amino acids in the central nervous system: assessment of the pharmacological actions of acamprosate. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000;60:343–362. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahchour A, Hoffman A, Deitrich R, de Witte P. Effects of ethanol on extracellular amino acid levels in high-and low-alcohol sensitive rats: a microdialysis study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:548–553. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahchour A, De Witte P. Excitatory and inhibitory amino acid changes during repeated episodes of ethanol withdrawal: An in vivo microdialysis study. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;459:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, York JL, Diaz LM, Samson HH, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Dopamine activity in the nucleus accumbens during consummatory phases of oral ethanol self-administration. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003;27:1573–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000089959.66222.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, Ramachandra V, Samson HH, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Accumbal dopamine concentration during operant self-administration of a sucrose or a novel sucrose with ethanol solution. Alcohol. 2004;34:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Molander A, Stomberg R, Soderpalm B. Taurine elevates dopamine levels in the rat nucleus accumbens; antagonism by strychnine. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:3225–3229. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K. Genetic selection for voluntary alcohol consumption in albino rats. Science. 1968;159:739–740. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3816.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA, Weiss F. Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:10663–10671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heien ML, Khan AS, Ariansen JL, Cheer JF, Phillips PE, Wassum KM, ightman RM. Real-time measurement of dopamine fluctuations after cocaine in the brain of behaving rats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10023–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504657102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol. Rev. 1992;72:101–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lada MW, Kennedy RT. Quantitative en vivo monitoring of primary amines in rat caudaze nucleus using microdialisis coupled by a flow-gated interface to capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:2790–2797. doi: 10.1021/ac960178x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehninger AL. Principles of Biochemistry. New York, NY: Worth Publishers Inc; 1982. pp. 535–641. [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RI, Hicks MP, Cagle SS, Kalivas PW. Ethanol exposure decreases glutamate uptake in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:326–333. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156086.65665.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander A, Lof E, Stomberg R, Ericson M, Soderpalm B. Involvement of accumbal glycine receptors in the regulation of voluntary ethanol intake in the rat. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:38–45. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150009.78622.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurmi M, Kiianmaa K, Sinclair JD. Brain ethanol levels after voluntary ethanol drinking in AA and Wistar rats. Alcohol. 1999;19:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive MF, Nannini MA, Ou CJ, Koenig HN, Hodge CW. Effects of acute acamprosate and homotaurine on ethanol intake and ethanol stimulated mesolimbic dopamine release. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;437:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson JC. The rat brain in stereotoxic coordinates. 4th. San Diego: Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Peris J, Zharikova A, Li Z, Lingis M, MacNeill M, Wu MT, Rowland NE. Brain ethanol levels in rats after voluntary ethanol consumption using a sweetened gelatin vehicle. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;85:562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SL. Diazepam potentiation by glycine in pentylenetetrazol seizures is antagonized by 7-chlorokynurenic acid. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994;47:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit HO, Justice JB. Dopamine in the nucleus accumbens during cocaine self-administration as studied by en vivo microdialisis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989;34:899–904. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling A, Bryceland J. Voluntary drug self-administration by nonhumans: a review. J. Psychedelic Drugs. 1979;11:185–190. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1979.10472103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quertemont E, Devitgh A, DeWitte P. Systemic osmotic manipulations modulate ethanol-induced taurine release: a brain microdialysis study. Alcohol. 2003;29:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert F, Bert L, Parrot S, Denoroy L, Stoppini L, Renaud B. Coupling on-line brain microdialysis, precolumn derivatization and capillary electrophoresis for routine minute sampling of O-phosphoethanolamine and excitatory amino acids. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;817:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DL, Venton BJ, Heien ML, Wightman RM. Detecting subsecond dopamine release with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry in vivo. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:1763–1773. doi: 10.1373/49.10.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux MJ, Supplisson S. Neuronal and glial glycine transporters have different stoichiometries. Neuron. 2000;25:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland NE, Nasrallah N, Robertson KL. Accurate caloric compensation in rats for electively consumed ethanol-beer or ethanol-polycose mixtures. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005;80:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis-Segura C, Spanagel R. Behavioural assessment of drug reinforcement and addictive features in rodents: an overview. Addict. Biol. 2006;11:2–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saul’skaya NB, Mikhailova MO, Gorbachevskaya AI. Dopamine-dependent inhibition of glycine release in the nucleus accumbens of the rat brain during food consumption. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2001;31:317–321. doi: 10.1023/a:1010342803617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman JG, Watson CJ, Kennedy RT. High-throughput automated post-processing of separation data. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1040:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou M, Ferrario CR, Schultz KN, Robinson TE, Kennedy RT. Monitoring dopamine in vivo by microdialysis sampling and on-line CE-laser-induced fluorescence Anal. Chem. 2006;78:6717–6725. doi: 10.1021/ac0608218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Watson CJ, Frantz KJ, Eppler B, Kennedy RT, Peris J. Differential increase in taurine levels by low-dose ethanol in the dorsal and ventral striatum revealed by microdialysis with on-line capillary electrophoresis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:1028–1038. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000131979.78003.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Diab ME, Friedman R, Henze LM, Lominac KD, Bowers MS. Accumbens neurochemical adaptations produced by binge-like alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:415–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth E, Lajtha A. Antagonism of phencyclidine-induced hyperactivity by glycine in mice. Neurochem. Res. 1986;11:393–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00965013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth E, Weiss B. Banay-Schwartz MN, Lajtha A. Effect of glycine derivatives on behavioral changes induced by 3-merca-ptopropionic acid or phencyclidine in mice. Res. Commun. Psychol. Psychiatry Behav. 1986;11:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;267:250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CE, Talla HH, Lin YY, Gaull GE. Taurine: biological update. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986;55:427–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Zuo H, Stobaugh JF. Continuos in vivo monitoring of amino acid necurotransmitters by microdialysis sampling with on-line derivatization and capillary electrophoresis separation. Anal. Chem. 1995;67:594–599. doi: 10.1021/ac00099a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.