Abstract

Objective

Patients with end-stage renal disease on maintenance hemodialysis are much more sedentary than healthy individuals. The purpose of this study was to assess the feasibility and safety of a 12-week intra-dialysis yoga intervention versus a kidney education intervention on the promotion of physical activity.

Design and Methods

We randomized participants by dialysis shift to either 12-week intra-dialysis yoga or an educational intervention. Intra-dialysis yoga was provided by yoga teachers to participants while receiving hemodialysis. Participants receiving the 12-week educational intervention received a modification of a previously developed comprehensive educational program for patients with kidney disease (“Kidney School”). The primary outcome for this study was feasibility based on recruitment and adherence to the interventions, and safety of intra-dialysis yoga. Secondary outcomes were to determine the feasibility of administering questionnaires at baseline and 12-weeks including the Kidney Disease-Related Quality of Life-36.

Results

Among 56 eligible patients approached for the study, 55% (n=31) were interested and consented to participation with 18 assigned to intra-dialysis yoga and 13 to the educational program. A total of 5 participants withdrew from the pilot study, all from the intra-dialysis yoga group. Two of these participants reported no further interest in participation. Three withdrawn participants switched dialysis times and therefore could no longer receive intra-dialysis yoga. As a result, 72% (13 of 18) and 100% (13 of 13) of participants completed 12-week intra-dialysis yoga and educational programs, respectively. There were no adverse events related to intra-dialysis yoga. Intervention participants practiced yoga a median of 21 sessions (70% participation frequency), with 60% of participants practicing at least 2 times a week. Participants in the educational program completed a median of 30 sessions (83% participation frequency). Of participants who completed the study (n=26), baseline and 12-week questionnaires were obtained from 85%.

Conclusions

Our pilot study of a 12-week intra-dialysis yoga and 12-week educational intervention reached recruitment goals, but less than targeted completion and adherence to intervention rates. This study provided valuable feasibility data to increase follow-up and adherence for future clinical trials to compare efficacy.

Keywords: hemodialysis, complementary and alternative medicine, end-stage renal disease, yoga, meditation, mind-body therapies

Introduction

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), especially those on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) are much more sedentary than healthy individuals.1 Sedentary behavior and poor physical performance are associated with increased mortality in this patient population. 2,3 Previous studies suggested that exercise can be beneficial among MHD patients, mostly by improving exercise capacity, muscle strength, and quality of life.4 Exercise may also improve other co-morbid conditions and symptoms among patients with ESRD, including blood pressure, fatigue, muscle weakness/cramping, and mood disorders. 5

The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) has recommended that nephrologists provide counseling to encourage physical activity for MHD patients.6 Different forms of exercise have been studied including aerobic exercise, resistance training, and combined aerobic exercise and resistance training both between dialysis sessions (inter-dialysis) and during actual dialysis (intra-dialysis).7 While these conventional exercise programs have demonstrated a very high safety profile with few adverse events reported, their reported efficacy has been not consistent. 7,8 Further, exercise counseling among nephrologists is low,9 and adherence of participants in clinical studies of exercise programs has been variable (39%-99%).7 There is precedent for more research to identify the most feasible exercise options among ESRD patients undergoing maintenance dialysis.

Originating in India from over 2000 years ago, yoga is mind-body practice becoming more prevalent in the United States.10 Yoga utilizes postures, breathing, and meditation in an effort to focus the mind and engage the body in low to moderate physical activity. Healthy individuals who use yoga report their practice as being important to maintain their overall health.10 Preliminary data suggest that yoga may benefit patients with chronic diseases by improving quality of life,11–15 cardiovascular risk factors and disease,16 and mood disorders.17,18

Among patients on MHD, yoga may positively influence quality of life, physical performance, and multiple co-morbidities associated with ESRD. However, no previous studies have utilized mind-body techniques during MHD. Interventions during hemodialysis would offer the benefit of convenience for the patient, and possible increased adherence to practice. Determination of the feasibility and safety of yoga during dialysis sessions is an essential first step towards future research on the clinical effectiveness and mechanisms of intra-dialysis mind-body exercises.

The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility and safety of a 12-week intra-dialysis yoga intervention versus an educational intervention among patients with ESRD receiving MHD. The pilot study was also used to train four yoga teachers to deliver the intervention for this specific population. In addition, we assessed the feasibility of a 12-week intra-dialysis educational program among patients with ESRD receiving MHD to inform development of a comparison group for future clinical trials.

Methods

Study Sample

Patients were recruited from an academic dialysis center between October 2012 and October 2013. Eligible patients were those on MHD for 3 or more months, Kt/V ≥ 1.2, expected to remain on hemodialysis for at least 6 months, and 18 years or older. Patients were excluded who had unstable cardiac disease (angina, life threatening arrhythmias), chronic lung disease requiring oxygen supplementation at rest or with ambulation, active cerebrovascular disease, major depression, cognitive impairment (MME ≤ 24), and current participation in an exercise or mind-body program/classes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and signed informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Study Design

To systematically recruit patients for each pilot study, we randomly assigned each dialysis shift to either intra-dialysis yoga or the educational program. We used permuted block randomization with varying block sizes for randomization. Assignments were sealed in sequentially numbered, opaque envelopes and opened by research staff prior to initiating recruitment. Research staff approached patients about the pilot study during dialysis sessions. Patients were given a verbal description and informational letter about the study based on assigned randomization (either intra-dialysis yoga or educational program).

Intervention

Intra-dialysis Yoga: In brief, the intra-dialysis yoga protocol consisted of yoga instruction and practice three times a week for 12 weeks. Participants had the opportunity to participate in 30 to 60 minutes of yoga during each session. Sessions were conducted during the first and second hour of dialysis. The yoga intervention consisted of slow body movements coordinated with breathing within the patients’ comfortable range of motion (See Table 1). Examples of movements coordinated with breathing include: ankle flexion/extension, knee flexion/extension, hip flexion/extension, hip abduction/adduction, and arm flexion/extension. Patients were seated in their routine chair for dialysis during the entire yoga session. The chair was reclined for some exercises and upright for others. In addition, patients used meditation and visualization techniques to enhance relaxation. The intra-dialysis yoga protocol prioritized participants’ capacity to perform the movements and their comfort doing so. The yoga program was designed in a gradual and progressive sequence over 12 weeks with the intention to increase patient safety while performing the yoga, to increase patient confidence to perform the yoga, and establishing sustainable behavioral and physical changes. Each participant was provided modified practices if he or she was unable to perform a given exercise throughout the study or during a specific session. When possible, participants were taught together as a group in specific areas of the dialysis unit, or alternatively individually when not feasible.

Table 1.

12-week intra-dialysis yoga intervention

| Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 3 |

Week 4&5 |

Week 6&7 |

Week 8 |

Week 9 & 0 |

Week 11&12 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postures | ||||||||

| Reclined chair | ||||||||

| • Hip flexion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Hip twist | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Anterior arm extension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Rest | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Hip abduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| • Knee extension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Upright chair | ||||||||

| • Knee extension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| • Knee extension and foot flexion | ✓ | |||||||

| • Arm extension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| • Foot flexion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| • Forward bend | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| • Chest expansion | ✓ | |||||||

| • Chest expansion and twist | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Breathing/ Inspiratory: Expiratory Ratio | ||||||||

| • Free observed breath | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| • Controlled breath: Inspiration <expiration |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| • Cooling breath: Inspiration<expiration |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Meditation | ||||||||

| • Visualize pleasant moving water | ✓ | |||||||

| • Visualize pleasant moving water over body |

✓ | |||||||

| • Visualize moving water with hand from abdomen to chest, and from chest away from body |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| • Visualize water moving with hand into body, up and down body, and then from chest away |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

The yoga intervention was designed to not interfere with the regular routine and continuity of hemodialysis. Each movement was selected and modified for the specific purpose of exercise during dialysis. To avoid potential disruption or harm to the access site, none of the proposed exercises involved movement of the vascular access site (i.e., only extremities without vascular access moved directly. For example, patients who had vascular access in one arm only performed unilateral arm movements in the free arm and the legs. Patients with vascular access in the chest moved both arms.

The intra-dialysis yoga protocol was developed by expert consensus with 3 yoga therapists from Yoga as Therapy North America and the principal investigator who is a certified yoga teacher and physician. All yoga sessions were taught by 4 certified yoga teachers with close supervision by principal investigator. All of the yoga teachers completed yoga teacher training programs accredited by Yoga Alliance, a nationally recognized organization that standardizes yoga certification. The principal investigator provided guidance and feedback to yoga teachers to develop and maintain fidelity of the yoga intervention. Usual care of patients continued as per routine management and protocol of the dialysis unit. Research staff and yoga teachers worked with dialysis staff to integrate yoga sessions during dialysis to avoid disruption of routine care.

Educational Program

The educational intervention comparison group consisted of a 12-module educational course based on the previous developed “Kidney School,” which was developed and maintained by the Medical Education Institute, Inc.19 The educational program was provided through printed materials in binders. Participants had an opportunity to complete 30 to 60 minutes of the educational curriculum during the first two hours of dialysis. Kidney School is a comprehensive, free, educational curriculum for people with kidney disease that is available in printed and online formats at www.kidneyschool.org.

Modules are written at the 6th grade reading level. Each module contained interactive questions to allow participants to evaluate and personalize their learning experience. Participants make entries that are incorporated into personal action plans. Participants were asked to complete assignments as outlined in the curriculum, but specifically told these assignments would not be graded. Modules were divided across 12 weeks in attempt to match the time of the yoga intervention for each session. The curriculum was introduced chair side by a research assistant who discussed each module, progress of each module and any participant questions. The research assistant met with participants at least once a week during the 12 weeks. While the research assistant was available for questions and guidance, participants completed the curriculum independently. Participants logged the length of time spent during each dialysis session on the curriculum. Usual care of patients continued as per routine management and protocol of the Vanderbilt Outpatient Dialysis.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this pilot study was the feasibility and safety of implementing intra-dialysis yoga among MHD patients. Feasibility was determined by successful recruitment of participants to the 12-week yoga pilot and adherence to the yoga practice based on: 1) Willingness to participate in practice sessions; and 2) Frequency and duration (minutes, continuous measure) of participation in practice session. Adherence was documented by yoga teachers during dialysis sessions. We also determined the feasibility of an educational program, Kidney School, as a comparison group. We documented number of participants recruited to the 12-week educational program and adherence to the curriculum based on: 1) Willingness to complete modules during dialysis, and 2) Frequency and duration (minutes-none, 10 or less, 11–20, 21–30, more than 30) of participation. Educational program participants self-reported adherence in a personal log which was collected by research staff.

Safety was monitored through documentation of routine blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, and temperature measurements during hemodialysis sessions. Research staff monitored and documented adverse events related to the yoga practice during the study including vascular access dysfunction, hypotensive or hypertensive episodes (during yoga practice, intra-dialysis, and inter-dialysis), muscle cramps, musculoskeletal injuries, cardiovascular events, hospitalizations, or deaths. The fidelity of yoga teaching by yoga teachers in training was assessed with a checklist. The checklist evaluated teaching regarding the quality of instruction and adherence to movements, breath, meditation as specified in the yoga protocol, and social interaction of yoga teachers with participants (e.g. eye contact, active listening, answering questions, non-verbal communication).

Research staff also administered questionnaires at baseline and 12 weeks to measure feasibility of data collection including the following instruments: health-related quality of life (Kidney Disease Quality of Life-36),20,21,22 fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness-Fatigue), 23–26 mood, (Profile of Mood States, 27 Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale),28 satisfaction with dialysis treatment (ESRD: Patient Satisfaction),29 sleep quality (Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index),30 and disease-related self-efficacy (modified version of Perceived Diabetes Self-Efficacy Scale for patients on maintenance hemodialysis).31

Statistical Analyses

We planned to enroll at least 16 patients to the intra-dialysis yoga intervention and 8 patients to the educational program for this pilot study (total of 24 participants). No prior information on magnitude of effect size for yoga was available in this population. We anticipated that this sample size would provide sufficient experience to determine if intra-dialysis yoga is safe and that both interventions were feasible among patients with ESRD.

Recruitment efforts were documented in terms of number of eligible patients approached, number who declined participation, and number successfully recruited. We estimate that among patients screened and eligible, 50% would be willing to participate in the study. Adherence was documented in terms of number of patients that completed the 12-week interventions and frequency of participation. We considered adherence to the interventions high if 80% of participants completed the entire 12-week protocol and 80% participated during dialysis at least two times per week (66% participation over 12 weeks). Adverse events were systematically tracked during the study period.

Yoga teachers were trained as a component of this pilot study and the consistency of their instruction of the intervention was evaluated by two observers with a checklist. We predicted minor variation in the administration of the intervention among trained teachers. If the fidelity was less than 80% during the study, teachers would undergo further training from expert yoga therapist with one-to-one tutorials with subsequent observation and re-evaluation of fidelity (in a “teach-to-goal” process).

We also assessed our ability to collect data with administration of questionnaires to be used in a future randomized controlled trial. As a feasibility study, this study was not powered to detect a difference in outcomes between the 12-week intra-dialysis yoga and the educational program. A priori, we had selected the Physical Component Summary of the Kidney Disease-Related Quality of Life-36 (KDQOL) as the outcome of interest to perform a power calculation based on preliminary effects of the two interventions. Differences in the changes of the KDQOL were explored with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Other measures were collected for feasibility purposes only. All other continuous data was reported as median with interquartile range and categorical data as percentages Analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (Version 22).

Results

After randomization by dialysis shift, we screened 73 patients receiving chronic outpatient hemodialysis in a single dialysis unit, of whom 56 (77%) were eligible for participation (Figure 1). Among patients approached, a total of 31 (55%) consented to either intra-dialysis yoga or Kidney School; a similar number of patients were interested in participation in the intra-dialysis yoga (58%) as Kidney School (62%). The demographic, biometric, clinical, and biochemical baseline characteristics are reported in Table 2. The median age of subjects in our study was 48 years (Interquartile range [ICQ] 34–61). An equal number of men and women enrolled into intra-dialysis yoga. A majority of patients in both intervention groups were African American (n=28, 90%), overweight or obese, and had hypertension (n=28, 90%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics1

| Characteristic | Yoga (n=18) | Kidney School (n=13) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, (n) | ||

| Male | 9 | 8 |

| Female | 9 | 5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 2 | 1 |

| African American | 16 | 12 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Age (years) | 48.2 (35.1–61.5) | 48.0 (32.0–58.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 83.8 (68.31–102.3) | 89.6 (71.2–106.2) |

| Height (m) | 1.7 (1.6–1.7) | 1.8 (1.7–1.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.1 (24.00–36.40) | 31.40 (23.85–34.70) |

| Comorbidities (n) | ||

| HTN | 17 | 11 |

| CHF | 1 | 3 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 3 |

| Biochemical | ||

| Albumin | 4.1 (3.9–4.3) | 4.0 (3.6–4.2) |

| Calcium | 9.5 (9.1–9.7) | 9.4 (8.9–10.1) |

| Kt/V | 1.4 (1.3–1.7) | 1.3 (1.2–1.6) |

| Potassium | 4.9 (4.5–5.5) | 4.8 (4.3–5.4) |

| Urea | 60.0 (44.0–74.3) | 59.0 (46.0–69.0) |

| Creatinine | 12.8 (10.3–14.9) | 12.2 (9.6–13.3) |

| Hemoglobin (dl) | 10.7 (10.1–11.6) | 11.2 (9.9–12.5) |

| Phosphorous | 6.1 (4.3–8.0) | 5.3 (5.1–6.5) |

| PTH Intact | 368.0 (201.2–692.8) | 273.1 (134.4–512.9) |

| Transferrin Saturation | 21.5 (17.8–27.0) | 24.0 (18.0–36.0) |

Median values (Interquartile range)

A total of 5 participants withdrew from the pilot study, all from the intra-dialysis yoga group. Two of these participants reported no further interest in participation. Three withdrawn participants switched dialysis shifts and therefore could no longer receive intra-dialysis yoga in the assigned shift. As a result, 72% and 100% of patients completed 12-week intra-dialysis yoga and educational programs, respectively. There were no adverse events related to intra-dialysis yoga during the 12-week period. During the study period, there were no hospitalizations among patients in the intra-dialysis yoga group and 4 hospitalizations in the Kidney School group. By the end of the study, all yoga teachers demonstrated greater than 80% fidelity for intervention delivery as measured by a checklist.

Patients in the intra-dialysis yoga group practiced yoga for a median of 60% of potentially available dialysis sessions and median of 70% of actually attended dialysis session. (See Table 3). Excluding absences from dialysis, 60% participants on average practiced yoga at least 2 times a week. Table 4 describes reasons for not practicing intra-dialysis yoga during the 12 weeks with the most common specific reason, outside of absence from dialysis, being patient refusal (18%). A large majority of refusals were due to patients sleeping, since patients were not woken up for the purpose of the study. Patients in the educational group could have completed 36 modules over 12 weeks, since we permitted make-up homework if absent from dialysis. Patients completed a median of 30.0 modules (83% participation frequency) during dialysis. Over 12 weeks, patients in the intra-dialysis yoga group practiced yoga a median of 407 minutes or 22 (IQR 26–31) minutes of yoga per dialysis session. Half of Kidney School participants reported participating in the educational program for 21 to 30 minutes per dialysis session.

Table 3.

Adherence to interventions1

| Intervention Yoga | |

|---|---|

| Total practiced sessions | 20.5 (14.8–27.5) |

| Frequency of missed dialysis sessions | 2.0 (1.8–2.5) |

| Participation frequency (%) | |

| All scheduled dialysis sessions | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) |

| Only attended dialysis sessions (excludes absences) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Duration (minutes) | |

| Total over 12 weeks | 407 (255–669) |

| Per dialysis session | 22 (12–24) |

| Kidney School | |

| Total completed modules during dialysis | 30.0 (26.0–31.0) |

| Frequency of missed dialysis sessions | 2.0 (0.3–3.8) |

| Participation frequency (%) | |

| All scheduled dialysis sessions | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) |

| Duration over 12 weeks | |

| None | 0.17 (0.11–0.22) |

| 10 or less minutes | 0.03 (0.0–0.06) |

| 11–20 minutes | 0.25 (0.11–0.36) |

| 21–30 minutes | 0.50 (0.39–0.61) |

| More than 30 minutes | 0 |

Median values (Interquartile range)

Table 4.

Reasons for not practicing yoga

| Reason | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Injury | 2 (1.7%) |

| Fatigue: | 0 |

| NV | 22 (19%) |

| Anxiety | 8 (7%) |

| Interference with patient care | 1 (0.9%) |

| Medical Complications: | 0 |

| Patient Refusal: | 21(18%) |

| Absence from dialysis | 23 (20%) |

| Other | 38 (33%) |

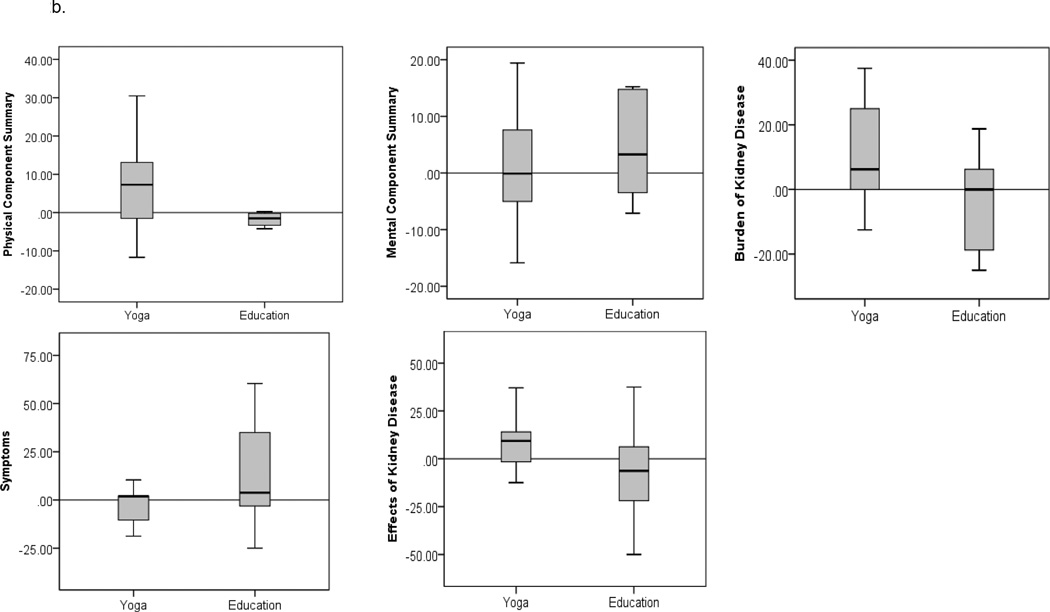

Among the 26 participants who completed the study, baseline and 12-week outcome measures were collected from 22 participants (n=12 yoga group, n=10 education group). Table 5 and Figure 2 present baseline and 12-week measures from the KDQOL. The intra-dialysis yoga group has positive changes in the Physical Component Summary, Effects of Kidney Disease, Burden of Kidney Disease, and minimal changes in the Mental Component Summary and Symptoms subscales. The educational group demonstrated positive changes in the Mental Component Summary and Symptoms, negative changes in the Effects of Kidney Disease, and minimal to no changes in Physical Component Summary and Burden of Kidney Disease sub-scales. Differences between intra-dialysis yoga and the educational programs for KDQOL as measured by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test were not significant.

Table 5.

Kidney-Disease Quality of Life-36 measures at baseline and 12 weeks1

| Intra-dialysis yoga (n=12) | Educational program (n=10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12-weeks | Change | Baseline | 12-weeks | Change | P value2 |

|

|

Physical Component Summary |

35.09 (26.07–49.85) |

42.38 (36.91–55.50) |

7.29 (−3.04–13.69) |

35.18 (28.68–43.44) |

34.49 (30.98–37.74) |

−1.51 (−5.64–2.17) |

0.18 |

|

Mental Component Summary |

55.55 (42.22–60.40) |

55.44 (49.14–59.47) |

−0.11 (−5.3–8.04) |

43.27 (39.56–55.15) |

54.57 (41.02–59.26) |

3.26 (−4.38–14.87) |

0.660 |

| Effects of Kidney Disease | 65.63 (−6.25–18.75) |

75.00 (0.00–25.00) |

9.47 (−6.25–18.75) |

71.88 (44.37–92.19) |

65.63 (45.32–85.94) |

−12.50 (−21.87–7.04) |

0.098 |

| Burden of Kidney Disease | 50.00 (31.25–81.25) |

68.75 (37.50–75.00) |

6.25 (0.00–25.00) |

62.50 (25.00–90.63) |

58.25 (18.75–90.63) |

0.00 (−20.31–9.38) |

0.149 |

| Symptoms | 83.33 (68.75–95.83) |

85.42 (76.56–93.23) |

1.89 (−14.59–6.25) |

79.54 (57.40–90.62) |

88.54 (74.48–94.27) |

3.79 (−3.64–40.0) |

0.354 |

Median values (Interquartile range)

Wilcoxon rank-sign test comparing change in intra-dialysis yoga group to educational program

Figure 2.

Changes in Kidney Disease-Related to Quality of Life Measures at Baseline and 12-weeks1

1 Median values (Interquartile range)

Changes in Kidney Disease-Related to Quality of Life Measures from Baseline to 12-weeks1

1 Median values (Interquartile range)

Discussion

Our study of intra-dialysis yoga among patients on MHD demonstrated reasonable feasibility of and no adverse events from the yoga intervention. About half of patients approached were interested in participating in the research study (55%) The patients who were recruited to the yoga intervention were predominately African American and equally male or female. The composition of our sample population is different than the general population that practices yoga which is predominately White and female.33 The number of participants that completed the yoga protocol, 72%, was below our goal of 80% completion. The number of participants that practiced yoga at least twice a week was also less than our goal (60% versus 80%). There were no adverse events associated with yoga during dialysis or between dialysis sessions during study period. Yoga teachers demonstrated high fidelity in administering the intervention. In addition, we demonstrated the feasibility of an educational comparison group, Kidney School, which exceeded enrollment goals and had a 100% study completion rate.

Our lower than target completion rate was a result of five participants withdrawing; three because of shift changes. We did not anticipate this number of shift changes among patients during the study period. To reduce this occurrence in the future, inquiring with patients and staff about desired or planned changes in dialysis shift during screening may be helpful. In addition, explicitly stating to the patient and staff that changing shifts will lead to study withdrawal and requesting schedule changes until after the study may potentially improve completion rates.

Adherence to intra-dialysis yoga was below our goal with overall of 60% practicing at least twice a week. Further increases to adherence may be possible with slight modification to our research protocol. First, Table 4 indicates that a common reason for not participating was nausea and vomiting. This was largely driven by a single participant who had chronic nausea and vomiting limiting participation in the study. Excluding this participant, 66% of participants practiced yoga at least twice a week. In the future, exclusion of patients with chronic nausea and vomiting may be necessary. Second, a large number of patients missed participation of a given session due to refusal as a result of being sleepy or sleeping. Yoga teachers were generally reluctant to wake patients. Based on our experience, one method to improve patient participation is to begin intra-dialysis yoga immediately at the beginning of hemodialysis session before he/she falls asleep or becomes drowsy.

Overall, the dose of intra-dialysis yoga was reasonable with a median practice of 22 minutes per dialysis session. The yoga protocol was designed to gradually increase the dose over 12 weeks. Given the low baseline physical function dialysis patients, a median of 60 minutes of mind-body practice a week may be sufficient to demonstrate therapeutic effects. Improving adherence as described above should effectively increase the dose of yoga.

The educational intervention, Kidney School, recruited similar number of participants as the yoga group, and demonstrated high retention of participants. Patients in the educational group also reported high levels of participation. In addition, participants reported similar dose to the yoga group (between 20 and 30 minutes per dialysis session). These data suggest that Kidney School as delivered was a reasonable comparison group to intra-dialysis in regards to matching the time and attention of the yoga group. However, there remain some differences between these groups. The intra-dialysis yoga group received more personal attention from the yoga teacher as compared to the educational group. Secondly, some participants interacted with each other during intra-dialysis yoga, which may produce a therapeutic group effect versus the educational group which was individually received and self-directed.

This pilot study aimed to inform the design of a larger clinical trial which would compare a 12-week intra-dialysis yoga intervention to an educational comparison group. A priori, we determined the primary outcome for the clinical trial to be the Physical Component Summary of the KDQOL. A 5 point increase in the Physical Component Summary has been correlated with a 10% increase in survival.2 Based on data from this pilot, we measured a non-statistically significant difference in means of 7.84 between intra-dialysis yoga and Kidney School from baseline to 12 weeks with a standard deviation of 10.68 for the Physical Component Summary. A larger clinical trial is necessary to measure if a difference between groups is clinically and statistically relevant.

There are limitations to our pilot study. First, yoga teachers were being trained during the intervention period, so that the intervention may have been administered less effectively. Since all yoga teachers demonstrated sufficient fidelity in teaching by the end of the study, this will not be a future limitation. Some patients were taught yoga in groups while others were taught individually. This may have produced variability in attention from yoga instructors and/or between research participants. Future efforts may focus on grouping participants together, though logistical barriers in dialysis units and patient preferences may limit this. The small sample size of our study lacks powers to measure difference in collected outcomes. Since our study recruited from a single dialysis site and trained one set of yoga teachers, our results are not generalizable. The educational group had an opportunity to make-up missed modules at future dialysis session which limits direct comparison of adherence to yoga by dialysis session. Also, we did not capture reasons why participants did not complete educational modules. The mechanism of how yoga may benefit the health of patients receiving MHD as compared to an educational group is unknown. As a complex behavioral intervention, yoga may affect health in various ways. Potential mechanisms for yoga’s affect that may be distinct from health education alone include physical exercise, 32,33 improved autonomic dysfunction (increase in parasympathetic and decrease in sympathetic nervous tone), 34–38 improved mood,39 stress reduction,40 increased self-efficacy,41 and contextual effects (attention from yoga teachers or group effect). Our study did not assess nutritional status or intake which may affect health outcomes among patients receiving MHD; for example nutritional supplements are commonly used among patients with ESRD. 32,42–44

In conclusion, we report the first study of intra-dialysis yoga, utilizing a tailored mind-body intervention for MHD patients. Our study reached recruitment goals, but less than targeted completion and adherence to intervention rates. This pilot provided valuable information in how to increase completion and adherence for future studies. A larger randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of intra-dialysis yoga to an educational program is warranted.

References

- 1.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Ng AV, et al. Physical activity levels in patients on hemodialysis and healthy sedentary controls. Kidney Int. 2000 Jun;57(6):2564–2570. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeOreo PB. Hemodialysis patient-assessed functional health status predicts continued survival, hospitalization, and dialysis-attendance compliance. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997 Aug;30(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, et al. Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Apr;24(5):822–830. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheema BS. Review article: Tackling the survival issue in end-stage renal disease: time to get physical on haemodialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008 Oct;13(7):560–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JE, Boivin MR, Jr, Hatchett L. Effect of exercise training on interdialytic ambulatory and treatment-related blood pressure in hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2004 Sep;26(5):539–544. doi: 10.1081/jdi-200031735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Apr;45(4 Suppl 3):S1–S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheema BS, Singh MA. Exercise training in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review of clinical trials. Am J Nephrol. 2005 Jul-Aug;25(4):352–364. doi: 10.1159/000087184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Painter P. Physical functioning in end-stage renal disease patients: update 2005. Hemodial Int. 2005 Jul;9(3):218–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2005.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen KL, Sakkas GK, Doyle J, Shubert T, Dudley RA. Exercise counseling practices among nephrologists caring for patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Jan;41(1):171–178. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birdee GS. Characteristics of Yoga Users: Results of a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, et al. Effects of yoga on inflammation and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008 Jun;14(5):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oken BS, Kishiyama S, Zajdel D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga and exercise in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(11):2058–2064. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129534.88602.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bower JE, Woolery A, Sternlieb B, Garet D. Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control. 2005;12(3):165–171. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately-Aldous S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psychooncology. 2006;15(10):891–897. doi: 10.1002/pon.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danhauer SC, Tooze JA, Farmer DF, et al. Restorative yoga for women with ovarian or breast cancer: findings from a pilot study. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008 Spring;6(2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley L, Dyakova M, Holmes J, et al. Yoga for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD010072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010072.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(12):884–891. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilkington K, Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Richardson J. Yoga for depression: the research evidence. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;89(1–3):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medical Education Institute I. [Accessed June 30, 2014];Kidney School. www.kidneyschool.org.

- 20.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994 Oct;3(5):329–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00451725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmichael P, Popoola J, John I, Stevens PE, Carmichael AR. Assessment of quality of life in a single centre dialysis population using the KDQOL-SF questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2000 Mar;9(2):195–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1008933621829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korevaar JC, Merkus MP, Jansen MA, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. Validation of the KDQOL-SF: a dialysis-targeted health measure. Qual Life Res. 2002 Aug;11(5):437–447. doi: 10.1023/a:1015631411960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, Gladman DD. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jul;66(7):936–939. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006 Jan 7;367(9504):29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67763-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadler S, Brain C, Catalano P, Einzig AI, Cella D, Benson AB., 3rd Randomized phase II trial of either fluorouracil, parenteral hydroxyurea, interferon-alpha-2a, and filgrastim or doxorubicin/docetaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer with quality-of-life assessment: eastern cooperative oncology group study E6296. Cancer J. 2002 May-Jun;8(3):282–286. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997 Feb;13(2):63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNair DMLM, Droppleman LF. Profile of mood states manual (revision) San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;3:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.John Newmann P MPH and Susan Pfettscher, DNSc, RN. End-Stage Renal Disease: Patient Satisfaction. [Accessed on 1/10/2009];The End-Stage Renal Disease Workgroup of Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care. http://www.mywhatever.com/cifwriter/content/41/pe4785.html2003.

- 30.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallston KA, Rothman RL, Cherrington A. Psychometric properties of the Perceived Diabetes Self-Management Scale (PDSMS) J Behav Med. 2007 Oct;30(5):395–401. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birdee GS, Phillips RS, Brown RS. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:654109. doi: 10.1155/2013/654109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009 Dec 10;(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Udupa K, Madanmohan, Bhavanani AB, Vijayalakshmi P, Krishnamurthy N. Effect of pranayam training on cardiac function in normal young volunteers. Indian.J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47(1):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernardi L, Passino C, Wilmerding V, et al. Breathing patterns and cardiovascular autonomic modulation during hypoxia induced by simulated altitude. J Hypertens. 2001;19(5):947–958. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200105000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernardi L, Sleight P, Bandinelli G, et al. Effect of rosary prayer and yoga mantras on autonomic cardiovascular rhythms: comparative study. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7327):1446–1449. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowman AJ, Clayton RH, Murray A, Reed JW, Subhan MM, Ford GA. Effects of aerobic exercise training and yoga on the baroreflex in healthy elderly persons. Eur.J Clin Invest. 1997;27(5):443–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.1340681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vempati RP, Telles S. Yoga-based guided relaxation reduces sympathetic activity judged from baseline levels. Psychol Rep. 2002;90(2):487–494. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.2.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013 Nov;30(11):1068–1083. doi: 10.1002/da.22166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4) doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r01068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryan S, Pinto Zipp G, Parasher R. The effects of yoga on psychosocial variables and exercise adherence: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2012 Sep-Oct;18(5):50–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duncan HJ, Pittman S, Govil A, et al. Alternative medicine use in dialysis patients: potential for good and bad! Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;105(3):c108–c113. doi: 10.1159/000097986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hess S, De Geest S, Halter K, Dickenmann M, Denhaerynck K. Prevalence and correlates of selected alternative and complementary medicine in adult renal transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2009 Jan;23(1):56–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowack R, Balle C, Birnkammer F, Koch W, Sessler R, Birck R. Complementary and alternative medications consumed by renal patients in southern Germany. J Ren Nutr. 2009 May;19(3):211–219. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]