Abstract

The current study compared traditional recovery homes for individuals with substance use disorders to ones that had been modified to feature culturally-congruent communication styles. Findings indicated significant increases in employment income, with the size of the change significantly greater in the culturally-modified houses. Significant decreases in alcohol use over time were also found, with larger decreases over time in the traditional recovery homes. Use of prescribed medications as well as days using drugs significantly decreased over time, but not differentially for those in the two types of recovery homes. The implications of these findings are discussed.

The size of the Latino population in the U.S. and projections for its growth require that substance abuse researchers pay increasing attention to the prevalence and treatment of alcohol abuse among this group (Alvarez, Jason, Olson, Ferrari, & Davis, 2007). National surveys indicate that this group has higher rates of substance-related problems (Caetano, 2003). Despite this risk, this segment of the U.S. population has less access to substance abuse treatment (Tighe & Saxe, 2006), reports less satisfaction with substance abuse interventions, and leaves treatment prematurely (Hser, Huang et al., 2004; White, Winn, & Young, 1998). Several large studies in various parts of the country also indicate that Latinos have poorer outcomes in alcohol and drug abuse treatment than individuals from other ethnic groups (Brecht, von Mayrhauser, & Anglin, 2000; McCaughrin & Howard, 1995).

Acculturation models address the changes that take place when cultural groups come into continuous first-hand contact (Berry, 2006) and these models may serve to guide the development and evaluation of culturally-modified interventions (Cauce, 2002). Acculturation is a multidimensional, bidirectional process of adaptation that results in changes in behavior, values/beliefs and identity (Berry, 2006). Cultural differences between clinicians and clients may lead to premature termination and lower levels of treatment involvement, which eventually lead to poorer outcomes (Castro & Tafoya-Barraza, 1997; Cervantes & Peña, 1998; Gil & Vega, 2001). A meta-analysis of studies evaluating mental health interventions indicates that cultural adaptations are beneficial, particularly when developed for specific ethnic groups (Griner & Smith, 2006). However, the role of culture in the process and outcome of substance abuse interventions is not sufficiently understood (Castro, Obert, Rawson, Lin, & Denne, 2003; Cervantes & Peña; Gil & Vega), because most interventions have not been empirically evaluated among ethnically diverse groups (Alegria et al., 2006).

The predictors of outcomes and ongoing utilization regarding aftercare services for Latinos have been particularly neglected by substance abuse researchers. For example, there are few studies that have examined the effectiveness of transitional living programs among Latinos with substance use disorders. Thus, there is little empirical evidence that treatment providers can use when planning aftercare services for this group. Exploring outcomes for Latinos seeking aftercare services is particularly important because substance abuse is a chronic condition that requires ongoing intervention (McKay & Weiss, 2001).

Oxford House (OH) was founded by recovering individuals whose goal was to provide sober housing and support to peers seeking long-term abstinence. Since its inception, OH has grown into an international network of over 1,500 homes serving over 10,000 men and women in the U.S. Since the early 1990’s, a team of researchers has studied OH (Jason, Olson & Foley, 2008), and their research has documented a number of benefits of the OH approach to alcohol abuse recovery among European and African Americans.

For example, in one study, Jason, Olson, Ferrari and LoSasso (2006) recruited 150 individuals who completed substance abuse treatment at alcohol and drug abuse facilities in the Chicago metropolitan area. Half were randomly assigned to live in an OH, while the other half received community-based aftercare services (“Usual Care”). Positive outcomes are evident in terms of substance use (i.e., 31.3% of participants assigned to the OH condition reported substance use at 24 months compared to 64.8% of “Usual Care” participants), employment (i.e., 76.1% of OH participants versus 48.6% of “Usual Care” participants were employed at the 24 month assessment) and days engaged in illegal activities during the 30 days prior to the final assessment (mean = 0.9 for OH and 1.8 for “Usual Care“ participants).

As part of this randomized study, 12 Latino participants had been recruited (8% of the total sample). Six of these participants had been randomly assigned to OH and six to the “Usual Care” condition. Data at the 24-month assessment indicated that length of time in OH ranged from two weeks to 24 months (mean = 9.1 months) for this sub-sample. Four of the six (67%) Latino OH participants left the House in good standing while two (33%) were evicted. Among these Latino OH participants, three of the six (50%) reported being abstinent 24 months after residential treatment. In contrast, only one of the six (17%) Latino participants in the Usual Care condition reported abstaining from substance use at 24 months. However, it is clear that this Latino sample is too small to draw any firm conclusions regarding the efficacy of the OH program for this population.

In another study, Jason, Davis, Ferrari and Anderson (2007) interviewed approximately 900 OH residents every four months for approximately one year. Findings from this study indicated that only 18.5% of the participants who left OH during the course of the study reported any substance use. Additionally, over the course of the study, increases were seen in participants’ abstinence self-efficacy and percentage of social network members who were abstainers or in recovery. In this study, 31 Latino participants were recruited, representing approximately 3% of the total sample. There were high levels of assimilation among the Latino participants on all acculturation measures. Additionally, cross-sectional analyses indicate no significant differences between Latino participants and matched samples of European and African American OH residents in terms of length of stay in OH, sense of community, or abstinence self-efficacy.

From this sample, Alvarez, Jason, Davis, Ferrari, and Olson (2004) interviewed nine Latino men and three Latina women living in OH. Most of the study’s participants were in their 20s or early 30s, U.S.-born and English-dominant. A majority of the participants reported criminal justice involvement and several episodes of residential treatment prior to moving to OH. Only two individuals were familiar with OH prior to entering residential treatment; the others had never heard about the program. Participants decided to move into an OH based on information they received from counselors and peers indicating that OH would facilitate their recovery. Prior to entering OH, participants were concerned that House policies would be similar to those of half-way houses they had experienced (i.e., too restrictive). Half of the individuals interviewed also had concerns about being the only Latino House member. Despite their initial concerns, participants reported overwhelmingly positive experiences in OH, with the majority of interviewees indicating that they “blended into the house” within their first few weeks. Most participants reported regular contact with extended family members and stated that family members supported their decisions to live in OH. The most commonly endorsed suggestion for increasing Latino representation in OH was to provide more information regarding this innovative mutual-help program. Another suggestion endorsed by a majority of participants was to provide opportunities for Spanish-speaking individuals to join the OH program. The study also indicates that many Latinos may not access OH because they are unfamiliar with the program, concerned about being the only Latino/a resident, or because there are no Spanish-speaking OHs.

In another study, Alvarez, Jason, Davis, Ferrari, and Olson (2007) focused on Latino participants’ perceptions of helpful aspects of OH. A model of recovery based on the participants’ experiences in OH emerged from this analysis. More specifically, participants stated that motivation to change was a necessary component of their recovery. Additionally, mutual help, emotional support, living in a sober environment, and being held accountable by peers were seen as the major therapeutic processes of the OH program. Findings based on grounded theory suggest that Latinos may benefit from OH.

However, these studies indicate that Latinos are underrepresented in OHs throughout the U.S. There is a need to test the effectiveness of OH with Latino individuals whose values, beliefs and behaviors present on a continuum of acculturation levels. In the present study, we compared the substance use, economic and legal outcomes of Latino individuals assigned to a culturally-modified OHs and to those assigned to a traditional OH. A culturally-modified house might provide more culturally-congruent experiences such as welcoming the involvement of extended family members and the use of more culturally-congruent communication styles, characterized by “personalismo” (an emphasis on relationships), “simpatia” (downplaying direct conflict in relationships in order to preserve harmony), and “respeto” (respect). Latino residents may experience a greater sense of comfort and affiliation or sense of community, and may be more likely to abstain from substance use, secure income employment, and reduce involvement with the criminal justice system. We hypothesized that on these dependent variables, those in the culturally-modified houses would have better outcomes.

Methods

Oxford Houses

Houses are single-sex dwellings, and members are expected to pay monthly rent and assist with chores. Houses generally have functional kitchens, laundry facilities, and common areas where residents conduct business meetings and spend social time. About eight individuals live in a house, and residents usually share a bedroom. Houses are located in multi-ethnic communities with access to public transportation and employment opportunities. Unlike other aftercare residential programs such as half-way houses, OH has no prescribed length of stay for residents.

Professionals are not involved with the OH. Residents are required to follow three simple rules: pay rent and contribute to the maintenance of the home, abstain from using alcohol and other drugs, and avoid disruptive behavior. Violation of the above rules results in eviction from the House. With overall governance occurs at weekly house meetings as well as at monthly chapter meetings, with each House operating democratically with majority rule (i.e., > 80% approval rate) regarding membership and most other policies. House members elect a president, secretary, treasurer, and comptroller who are responsible for conducting and recording House meetings, keeping financial records, and paying House bills. Status differences between residents are avoided by elections for new House officers held every six months. House members address those who do not follow House guidelines at regularly scheduled meetings, special meetings, or through fines or contracts, which specify desired behaviors and consequences of rule-breaking. During meals, recreational activities, weekly meetings, spontaneous or planned one-on-one meetings, and while working together on chores, OH residents provide one another with social support specific to the areas of abstinence, finding employment, and attending treatment and 12-step meetings.

The present study compared the traditional OH model versus houses designed specifically for Latinos. “Traditional” OHs are ethnically mixed and conduct interactions in English. In the culturally-modified OHs, all residents were Latino, and participants had the option of speaking either English or Spanish or a mixture of both languages. In these houses, residents could address experiences that may be more specific to Latino culture such as the involvement of family in a person’s recovery activities. In addition, residents of culturally-modified OHs could more easily use culturally-congruent communication styles, characterized by “personalismo,”“simpatia,”), and “respeto.” . There were three culturally-modified OHs and 26 traditional OHs used in the study. The two male and one female culturally-modified OHs were established for the purpose of this study.

Participants

Participants were recruited from multiple community-based organizations and health facilities from a large metropolitan area in the Midwest. The research team included a bilingual/bicultural project director, graduate students, research assistants and volunteers of Latino background. A Latino OH alumnus with more than three years of sobriety helped recruit participants and helped establish the culturally-modified Latino Houses.

The inclusion criteria required that participants: a) were of Latino background, b) had successfully participated in a substance abuse treatment program and c) were currently abstinent from alcohol and drugs. Those interested in continuing their recovery process in the OH were instructed to contact the recruiter or the project director. Potential participants were explained that they could either be placed in a traditional OH or in a Latino OH that only served Latinos. What determined placement was most often which house had an available opening in the Chicago metropolitan area. If a participant was only Spanish speaking, we would only place that person in a traditional house if there was one other Spanish speaking resident who could also speak English. Recruiters explained that participation in the study was entirely voluntary and that did not exclude them from being assigned to an OH. If interested, participants gave informed consent by signing the consent form provided by the interviewer. Consent forms were translated into Spanish. Individuals who opted to participate were transported to the Latino OH by the recruiter and interviewed by a group of OH alumni. Assessment was administered in both English and Spanish in the treatment facility from which they were recruited, participant’s house or in the Center for Community Research. Participants received $30 after completing the baseline survey and another $30 after completing the 6 month follow-up survey.

Measures

Demographics

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect participants’ information including age, gender, place or birth, years in the U.S. and treatment setting.

Addiction Severity Index Multimedia Version (ASI-MV/S-ASI-MV; Butler et al., 2001; Butler, Redondo, Fernandez, & Villapiano, 2008)

This instrument is a CD ROM-based simulation of the 5th Edition of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992). ASI assesses problems during the individual’s lifetime and during the 30 days prior to the interview in seven areas: alcohol use, drug use, illegal activity, interpersonal and family relations, medical problems, employment, and psychiatric problems. Key outcome variables for this study included income from employment and illegal activities as well as use of Use of prescribed medications for psychiatric or medical problems. In addition, ASI assessed whether the individuals were currently on probation or parole. The test-retest reliability of the English and Spanish ASI-MV composite scores is comparable to that of the traditional ASI (i.e., correlations range from .80 to .90 for all but the family/social composite scores).

Form-90 Timeline Follow-back (Miller, 1996)

This instrument provides a linear measure of alcohol and substance consumption within a 180-day time span (e.g., Simpson, Xie, Blum & Tucker, 2011). Because our study had a six month follow-up, we wanted to assess substance use during the entire six month period form the baseline assessment. The three primary outcome measures of the Form-90 that were number of days using alcohol and number of days using drugs. The Form-90 was translated into Spanish using translation and back-translation procedures along with regular discussions among team members by a bilingual team that included a professional translator, a psychologist, and a psychology graduate student (W. Miller, personal communication, October, 2005). The Form-90 had been used in several studies with Latino samples to produce valid data (Arroyo, Miller et al., 2003; Arroyo, Westerberg et al., 1998).

Bi-dimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS; Marin & Gamba, 1996)

This scale was used to measure Spanish proficiency and language use. The BAS is an empirically-derived measure, which has three subscales (language use, language proficiency, and electronic media). The three scales demonstrate high alphas (.81 - .97) and correlate highly with other behavioral measures of acculturation such as generation in the U.S. and proportion of life spent in the U.S. (Marin & Gamba,1996). The English and Spanish versions of the BAS were developed simultaneously by the scale’s authors, who are both bilingual and bicultural. The psychometric properties of both versions of the scale were also evaluated at the time of scale construction (Marin & Gamba,1996).

Values

At the follow-up interview, participants were asked about whether they celebrated Latino holidays in their OHs (yes, no). They were also asked how often they listened to Spanish music and how often they cooked ethnic foods in their OHs (1 = daily, 2 = several times a week, 3 = once a week, 4 = every 2-3 weeks, 5 = once a month, to 6 = less than once a month). Finally, they were asked “house members respect my cultural values and traditions” (1= strongly agree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

Results

Participants

There were 120 Latino participants assigned to either a culturally-modified or a traditional OH. Fifteen individuals declined to participate in the study. Seventy percent (N = 84) of the 120 participants were available for the six month follow-up interview. There was not a significant association between condition and drop out. We next examined those 84 who remained in the study versus those 36 who dropped out. There were no significant differences in terms of age, education years, income, days in which alcohol was consumed over the past 180 days, and the number of days participants used drugs in the past 180 days. For the 84 individuals with baseline and follow-up date, there were 39 individuals in the traditional OH and 45 in the culturally-modified OH. We next examined if there were significant baseline sociodemographic differences between the groups (see Table 1). There were no significant differences among demographic variables for the traditional versus culturally-modified OHs. There were also no significant differences in the number of days spent in the traditional OH versus the culturally-modified OH during the time from the baseline to follow-up (115 versus 100 days, p = .40). Although we had many possible outcomes of interest, given the small sample size, we limited our selected outcomes to those most relevant, including employment, substance use, legal and psychological status.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Valid Latino Sample by O.H. Condition Baseline (N= 84) and Follow-Up (N= 84)

| Baseline (N=84) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Modified OH | Traditional OH |

|||

|

| ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | p | ||

| Age | 35.8 (10.0) | 37.4 (10.3) | ||

| Education | 11.5 (1.9) | 11.3 (2.4) | ||

| % (n) | % (n) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 75.6 (34) | 84.6 (33) | ||

| Female | 24.4 (11) | 15.4 (6) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Puerto Rican | 51.1 (23) | 43.6 (17) | ||

| Mexican | 35.6 (16) | 41.0 (16) | ||

| Other | 13.3 (6) | 15.4 (6) | ||

| Religious Preference | ||||

| Catholic | 33.3 (15) | 28.2 (11) | ||

| Other | 15.1 (23) | 48.7 (19) | ||

| None | 15.6 (7) | 23.1 (9) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/ Remarried | 8.9 (4) | 2.6 (1) | ||

| Separated | 17.8 (8) | 17.9 (7) | ||

| Divorced | 20.0 (9) | 20.5 (8) | ||

| Never Married | 53.3 (24) | 59.0 (23) | ||

| Living Arrangements a | ||||

| With sexual partner/ children | 20.0 (9) | 23.1 (9) | ||

| With Parents/ Family | 33.3 (15) | 25.6 (10) | ||

| With friends | 4.4 (2) | 15.4 (6) | ||

| Alone | 17.8 (8) | 17.9 (7) | ||

| Controlled environment | 8.9 (4) | 7.7 (3) | ||

| No stable arrangements | 15.6 (7) | 10.3 (4) | ||

| Employment pattern a | ||||

| Full-time | 46.7 (21) | 30.8 (12) | ||

| Part-time (regular hours) | 11.1 (5) | 12.8 (5) | ||

| Part-time (irregular hours) | 15.6 (7) | 20.5 (8) | ||

| Unemployment | 13.3 (6) | 23.1 (9) | ||

| Other | 11.1 (5) | 12.8 (5) | ||

| Substance of major problem | ||||

| Alcohol | 22.2 (10) | 23.1 (9) | ||

| Heroin/Opiates/Analgesics | 22.2 (10) | 25.6 (10) | ||

| Cocaine/Amphetamines | 15.6 (7) | 5.1 (2) | ||

| Cannabis | 13.3 (6) | 10.3 (4) | ||

| Alcohol & one or more drugs | 24.4 (11) | 30.8 (12) | ||

| More than one, not alcohol | 2.2 (1) | 5.1 (2) | ||

| Lifetime Psychological status | ||||

| Attempted Suicide | 28.9 (13) | 28.2 (11) | ||

| History of psych meds | 53.3 (24) | 56.4 (22) | ||

| History of emotional abuse | 68.9 (31) | 51.3 (20) | ||

| History of physical abuse | 46.7 (21) | 64.2 (18) | ||

| History of sexual abuse | 20.0 (9) | 10.3 (4) | ||

| O.H. entry prompted by legal system | 17.8 (8) | 23.1 (9) | ||

Within the past 3 years

Continuous Outcomes

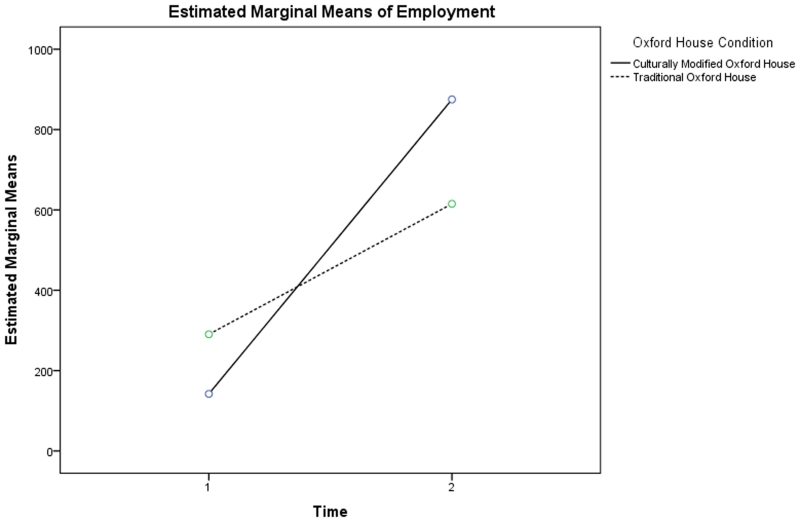

Table 2 presents the primary outcome variables. Using a two (time) by two (condition) mixed ANOVA, we examined changes in key continuous outcome variables. For income due to employment, there were significant time [F(1,82) = 29.94, p < .01, eta2p = .27] and interaction effects [F(1,82) = 4.46, p = .04, eta2p = .05], but the condition effect was not significant [F(1,82) = .19, p = .66, eta2p < .01]. Given the significant interaction effect (see Figure 1), we also examined simple main effects. For those in the culturally-modified OH, the mean difference in amounts of money earned when comparing baseline to follow-up data was $733 (p < .01), and for the traditional OH, the mean difference was $325 (p = .02). Therefore, residents in both types of recovery homes earned significantly more money over time. At baseline, there was a $148 difference in income of the residents within the two types of homes, which was not significant (p = .21). At the six month follow-up, there was a $260 difference in incomes of the residents within the two types of recovery homes, which was also not significant difference (p = .18) However, there was a significant interaction effect (see Figure 1); whereas those in the tradition OH earned more money than those in the culturally-modified OH at baseline, by the follow-up, those in the culturally-modified OH earned more income than those in the traditional OH. From these analyses, the size of the change in the culturally-modified OH was significantly greater than the change in the traditional OH.

Table 2.

Substance Use of Valid Latino Sample by O.H. Condition (N=84) and Follow-Up (N=84)

| Baseline (N=84) |

Follow-Up (N= 84) |

Group | Time | Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Modified OH | Traditional OH | Modified OH | Traditional OH | ||||

|

| |||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | p | p | p | |

| Income a | |||||||

| Employment | 142.0 (486.3) | 290.5 (585.2) | 875.0 (928.6) | 615.1 (831.2) | ** | * | |

| Illegal activity | 17.8 (119.3) | 56.4 (204.9) | 13.3 (89.4) | 146.2 (802.2) | |||

| Timeline Follow-Back b | |||||||

| Days consumed alcohol | 19.8 (35.2) | 37.6 (52.3) | 5.9 (19.1) | 2.8 (10.1) | ** | * | |

| Days used drugs | 52.8 (52.0) | 50.4 (55.9) | 15.1 (33.2) | 8.7 (30.8) | ** | ||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thirty-day Psychological Status | |||||||

| Psych meds | 37.8 (17) | 41.0 (16) | 20.0 (9) | 5.1 (2) | ** | ||

| Legal Status c | |||||||

| On probation/parole | 28.9 (13) | 43.6 (17) | 24.4 (11) | 46.2 (18) |

In the past 30 days

In the past 180 days

Current

p<.05

p<.01

Figure 1.

Changes in Employment over time

For illegal activity, Table 2 indicates that there were directional increases for the traditional OH but decreases for the culturally-modified OH, but there were no significant time [F(1,82) = .48, p = .50, eta2p = .01], condition [F(1,82) = 1.84 , p = .18 , eta2p = .02], or interaction effects [F(1,82) = .57, p = .45 , eta2p = .01].

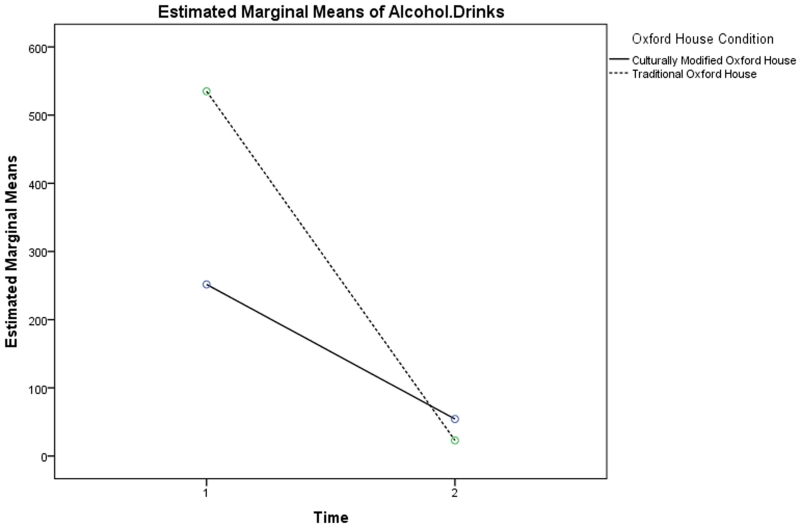

For days consumed drugs, there were significant decreases over time [F(1,82) = 42.21, p = .00, eta2p = .34], but not significant condition [F(1,82) = .34 , p = .56 , eta2p = .00], or interaction effects [F(1,82) = .11, p = .74 , eta2p = .00]. Thus, residents of both types of houses evidenced decreases in drug use. For days consumed alcohol, there were significant time [F(1,82) = 24.97, p < .00, eta2p = .23] and interaction effects [F(1,82) = 4.61 , p = .04 , eta2p = .05], but not significant condition effects [F(1,82) = 1.93, p = .17. , eta2p = .02]. Given the significant interaction effect (see Figure 2), we also examined simple main effects for the number of days alcohol was consumed. For those in the culturally-modified OH, the number of days alcohol was consumed significantly decreased 13.89 days (p =.04) from baseline to the 6 month follow-up, and for the traditional OH, there was also a significant decrease of 34.82 days (p < .01). Therefore, residents in both types of recovery homes evidenced significantly fewer days using alcohol over time. At baseline, there was not a significant difference (p = .07) between the number of days consuming alcohol (17.84 days) between the two types of homes. At the six month follow-up, there was also not a significant difference (p = .37) between days using alcohol (3.09 days) within the two types of recovery homes. However, as there was a significant interaction effect, as evident in Figure 2, those in the tradition OH consumed alcohol for more days than those in the culturally-modified OH at baseline, but by the follow-up, those in the tradition OH consumed alcohol for fewer days than those in the culturally-modified OH. From these analyses, the size of the change in the traditional OH was significantly greater than the change in the culturally-modified OH.

Figure 2.

Changes in Days Consuming Alcohol over Time

Dichotomous outcomes

For the dichotomous outcome variable use of prescribed medications for psychiatric or medical problems, a generalized estimating equation was used. This analysis allowed a within subjects factor for time, a between subjects factor for condition, and a between by within interaction. For this variable, there was a significant change over time (B = 1.16, x2= 8.13, p < .01, OR = 3.18) but no significant condition (B = .14, x2=.09, p = .76, OR = 1.15) or interaction effect (B = −.64, x2= 1.50, p =.22, OR = .53). These findings indicate that this outcome variable decreased over time but not differentially by condition.

Finally, for the dichotomous variable probation or parole, there were no significant time (B = −.10, x2= .20, p = .65, OR = .90), condition (B = .64, x2=1.95, p = .16, OR = 1.90) or interaction effects (B = .33, x2= .84, p =.36, OR = 1.39).

Acculturation

Given the small sample size, we were able to evaluate one three way interaction effect with the Bi-dimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics. We used a multilevel model with observations nested within individuals; no random effects were included in this model. Time-point was treated as a time-varying covariate, whereas all other predictors were time-invariant covariates, and the dependent variable was days using alcohol. There were no significant time [b = 38.97, t(160) = 1.41, p = .16], condition [b=28.62, t(160) = 1.13, p = .27], time by condition interaction [b = −22.97, t(160) = −.63, p = .53], or three way interaction effects[b = 16.25, t(160) = 1.24, p = .22]. However, there was a significant main effect of acculturation [b = 27.63, t(160) = 3.93, p < .01], indicating that on average, being less acculturated was associated with greater initial alcohol use. However, the time by acculturation interaction was significant [b = −27.43, t(160) = −2.75, p < .01], indicating that acculturation affected the alcohol outcomes over time. Although lower levels of acculturation were related to higher alcohol use at baseline, lower acculturation also related to greater decreases in alcohol use over time.

Values

Regarding celebrating Latino holidays, 33% of those in the culturally-modified OHs responded yes versus 7% in the traditional OHs (x2 (1, N = 84) = 8.16, p < .01). Those in the culturally-modified OHs listened to significantly more Spanish music in their OHs compared to the traditional OHs [Ms = 2.49 versus 3.89, t(80) = −3.44, p < .01]. Those in the culturally-modified OH listened to Spanish music more than once a week whereas those in the traditional OHs listened to it about every 2-3 weeks. Those in the culturally-modified OHs more frequently cooked ethnic food in their OHs [Ms = 1.89 versus 3.10, t(82) =−3.40, p < .01]. Those in the culturally-modified OHs cooked ethnic foods several times a week whereas those in the traditional OHs cooked this food only once a week. Finally, there were no significant differences when those in the culturally-modified houses versus traditional OHs were asked if house members respected their cultural values and traditions [Ms = 3.80 versus 3.64, t(82) = .66, p= .51] indicating that house members tended to agree with this statement, although scores were directionally higher and better for those in the culturally-modified OHs.

Discussion

The studies major findings were that significant increases in employment income were found over time for residents of both types of OHs, with the size of the change significantly greater in the culturally-modified houses. There were also significant decreases in alcohol use over time, with larger decreases in the traditional recovery homes. Additionally, those who were less acculturated to U.S. culture had greater reductions in their use of alcohol over time. Use of drugs as well as prescribed medications for psychiatric or medical problems significantly decreased over time, but not differentially for those in the two types of recovery homes. Significant changes did not occur for probation or parole, but there might not have been enough time for this outcome to change, given complexities of the criminal justice system. Overall, these findings suggest that both types of recovery homes appear to promote at least short term recovery, with the culturally-modified homes obtaining better outcomes for employment whereas the traditional recovery homes having better outcomes for reductions in days using alcohol. These results add to the literature that the ability to secure stable housing is associated with successful treatment outcomes (Humphreys et al., 1999).

Our study recruited and interviewed people during the time period of 2009 to 2012, when there was a major recession in the US. Therefore, increases in income as well as decreases in alcohol, drug and prescription medicines for psychiatric and medical conditions occurred during a time where employment opportunities were even more limited for individuals, particularly those with former substance use problems. These positive outcomes for those provided an OH highlight the importance of these settings for Latino individuals needing ongoing support after substance abuse treatment. However, without a pure control group, it is unclear if similar positive outcomes might have occurred without being provided an OH. It is also unclear why those provided the traditional OHs appeared to have better outcomes for alcohol consumption whereas those provided the culturally-modified houses had better outcomes for employment.

Higher income over time in the culturally-modified houses might be due to characteristics such as having high entitativity (i.e., a tightly knit group) rather than low entitativity (i.e., reflecting looser and more temporary associations) (Crawford, Sherman, & Hamilton, 2002). Higher levels of cohesion are found among group members sharing common behaviors, common emotions, similar cognitive accounts, and common physical characteristics. In addition, tightly knit groups moderate such phenomenon as stereotyping (Rydell, Hugenberg, Ray, & Mackie, 2007), impression formation (Dasgupta, Banaji, & Abelson, 1999), and attitude change (Rydell & McConnell, 2005). Similarly, the presence of the cultural value familism in the culturally-modified OH, residents make it a priority to “checkup” on each other’s job situations and provide various employment leads (Contreras et al., 2012). In other words, in a culturally-modified OH, residents may be more comfortable with their ethnic culture, have greater proximity, homogeneity, dedication to common purpose, and collective behaviors, and these factors may lead to more opportunities to share job leads and to have better economic outcomes.

While findings did indicate that those in the culturally-modified OHs did celebrate significantly more Latino holidays, listened to more Latino music and cooked more ethnic food, there were no significant differences on general feelings about other members respecting their cultural values and differences. This latter finding might help explain why no significant differences were found in terms of number of days that participants resided in the OHs, and outcomes for alcohol use were even more positive in the traditional OHs. These latter findings might have also been influenced by the fact that the traditional OHs had already been established and had more experience whereas the culturally-modified OHS all were established for the study and thus had less experience. Still, the outcomes suggest that it is possible that both types of houses provided Latinos with the types of culturally sensitivity and support that was needed to achieve positive outcomes.

Findings reviewed in the introduction indicate that Latinos are underrepresented in OHs. Individuals from this ethnic group are not even well-represented in OHs located in states that Latinos comprise a significant proportion of the population (i.e., Texas, Illinois, and New Jersey). In contrast, African Americans actively utilize OH, and their length of stay may equal or exceed that of European Americans (Jason et al., 2007). The reasons for the under-representation of Latinos in OH include lack of familiarity with the program, concerns about being the only Latino resident, and possibly lack of English-language skills. Culturally-modified OHs can provide more culturally and linguistically relevant peer interactions, but as indicated above, somewhat comparable results were found for both types of houses. There is a need for more studies examining the impact of cultural variables on the retention and success in OHs for Latinos, as it could add to our understanding of the influence of culture on outcomes in aftercare programs for this underserved and growing population.

Our prior research indicates that when OH residents develop social networks that do not support substance use, they are more likely to remain abstinent (Jason et al., 2007). We did not have the power to test for more than one three way interaction effects, and at least for the outcome variable days using alcohol, we did not find that the less assimilated Latinos did better in terms of sobriety in a culturally-modified OH. Conversely, we did not find that those individuals who are more assimilated and more comfortable and proficient in mainstream American culture were more likely to develop sobriety in traditional OHs. We did find that over time, acculturation status did moderate the use of alcohol, but it was not specific for either type of recovery home. Those who were less acculturated did evidence the largest reductions in alcohol use. As discussed above, cultural factors have been postulated to have an impact on social support processes in recovery (Cervantes et al., 2003; Hohman & Galt, 2001; Waters, et al., 2002). Future research will need to be devoted to explore whether other outcomes for participants are moderated by their level of acculturation.

There were several limitations in this study, including a small sample. In addition, we did not randomize participants to different types of houses, and this was due to the fact that when individuals were recruited, we needed to find housing for them relatively quickly, and there were not always openings in the different houses. In addition, the length of time was relatively brief, with only data collected at a 6 month follow-up. Average duration of stay was only about 3 months, but this was partly due to the collecting length of time at 6 months following entry into the homes. By the time the actual study had finished all data collection, we did go back and found that there continued to be no significant differences in the two conditions, with those in the traditional OHs living in the houses for an average of 115 days versus 100 days in the culturally-modified houses.

Our study found that both types of recovery houses are good placements for Latinos. There is certainly a need for more community based housing supports for Latinos following substance abuse treatment. The findings from the present study could be used to help substance abuse case managers and counselors make more informed decisions about referrals of Latinos to appropriate recovery home placements.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Randy Ramirez, Gilberto Padilla, Rory Murray, Leon Venable, and Richard Albert for their help with the study. Our thanks also to Gabriella Leon, Gloria Segovia, Daisy Gomez, Roberto Luna, Elbia Navarro, Sandy Rodriquez, Sharitza Rivera, and Leslie Mendoza. We also thank Steve Miller for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

The authors appreciate the financial support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA grant numbers AA12218 and AA16973). We also appreciate the revolving loan funds and support provided by the Illinois Department of Alcohol and Substance Abuse.

Contributor Information

Leonard A. Jason, DePaul University

Julia A. DiGangi, DePaul University

Josefina Alvarez, Adler School of Psychology.

Richard Contreras, DePaul University.

Roberto Lopez, DePaul University.

Stephanie Gallardo, DePaul University.

Samantha Flores, DePaul University.

References

- Alegria M, Vera M. Building effective research teams when conducting drug prevention research with minority populations. In: De La Rosa MR, Segal B, Lopez R, editors. Conducting drug abuse research with minority populations: Advances and issues. Haworth; New York: 1999. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, Davis MI. Substance abuse prevalence and treatment among Latinas/os. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6:115–141. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, Olson BD, Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR. Heterogeneity among Latinas and Latinos in substance abuse treatment: Findings from a national database. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;16:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo J, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on long-term outcome in three alcohol treatment modalities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:98–104. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo J, Westerberg VS, Tonigan JS. Comparison of treatment utilization and outcome for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:286. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation. In: Grusec J, Hastings P, editors. Handbook of socialization research. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, VonMayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Predictors of relapse after treatment for methamphetamine use. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:211–20. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SF, Budman S,H, Goldman LJ, Newman FL, Beckley KE, Trottier D, Cacciola JS. Initial validation of a computer-administered Addiction Severity Index: The ASI-MV. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:4–12. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SF, Redondo JP, Fernandez K, Cunningham JA, Villapiano A. Validation of the Spanish Addiction Severity Index–Multimedia Version (S–ASI–MV) 2005. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Obert JL, Rawson RA, Lin CV, Denne R. Drug abuse treatments with racial/ethnic clients. In: Bernal G, Trimble JE, Burlew AK, Leong FTL, editors. Handbook of Racial and Ethnic Minority Psychology. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. pp. 539–560. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Tafoya-Barraza HM. Treatment issues with Latinos addicted to cocaine and heroin. In: Garcia GG, Zea MC, editors. Psychological interventions and research with Latino populations. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 1997. pp. 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM. Examining culture within a quantitative empirical research framework. Human Development. 2002;45:294–298. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Kappos B, Duenas N, Arellano D. Culturally Focused HIV Prevention and Substance Abuse Treatment for Hispanic Women. Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. 2003;2:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes R, Pena C. Evaluating Hispanic/Latino programs: Ensuring cultural competence. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1998;16:109–131. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras R, Alvarez J, DiGangi J, Jason LA, Sklansky L, Mileviciute I, Navarro E, Gomez D, Rodriguez S, Luna R, Lopez R, Rivera S, Padilla G, Albert R, Salamanca S, Ponziano F. No place like home: Examining a bilingual-bicultural, self-run substance abuse recovery home for Latinos. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. 2012;3:2–9. doi: 10.7728/0303201202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MT, Sherman SJ, Hamilton DL. Perceived entitativity, stereotype formation, and the interchangeability of group members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(5):1076–1094. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Siles R, Bracamontes E. Acculturation: A psychological construct of continuing relevance to Chicana/o psychology. In: Velasquez RJ, Arellano LM, McNeill BW, editors. The handbook of Chicana/o psychology and mental health. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N. J.: 2004. pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Banaji MR, Abelson RP. Group entitativity and group perception: Associations between physical features and psychological judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:991–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorpade J, Lackritz J, Singh G. Psychological acculturation of ethnic minorities into white Anglo American culture: Consequences and predictors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34:1208–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA. Latino drug use, scope, risk factors and reduction strategies. In: Aguirre-Molina M, Molina CW, Zambrana RE, editors. Health issues in the Latino community. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2001. pp. 435–458. [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice and Training. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman MM, Galt DH. Latinas in treatment: Comparisons of residents in a culturally specific recovery home with residents in non-specific recovery homes. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2001;9:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Anglin D. Relationship between drug treatment services, retention, and outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:767–774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Mankowski ES, Moos RH, Finney JW. Do enhanced friendship networks and active coping mediate the effect of self-help groups on substance abuse? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;21:54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02895034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Davis MI, Ferrari JR, Anderson E. The need for substance abuse aftercare: A longitudinal analysis of OH. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:808–813. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Ferrari JR, Lo Sasso AT. Communal housing settings enhance substance abuse recovery. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1727–1729. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Foli K. Rescued lives: The OH approach to substance abuse. Routledge; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Pechota ME, Bowden BS, Kohner K, Pokorny SB, Bishop P, Quintana E, Sangerman C, Salina D, Taylor S, Lesondak L, Grams G. OH: Community living is community healing. In: Lewis JA, editor. Addictions: Concepts and Strategies for Treatment. Aspen Publications; Gaithersburg, MD: 1994. pp. 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Roberts K, Olson BD. Attitudes toward recovery homes and residents: Does proximity make a difference? Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33:529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Schober D, Olson BD. [Accessed June 13, 2008];Community involvement among second-order change recovery homes. The Australian Community Psychologist. 2008 20:73–83. Available at: http://www.groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/20(1)-08-Jason-etal.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Test of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new mea surement of acculturation for Hispanics: The bi-dimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- McCaughrin WC, Howard DL. Variations in outpatient substance abuse treatment units with high concentrations of Latino versus White clients: Client factors, treatment experiences and treatment outcomes. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:509–522. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Weiss RV. A review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups: Preliminary results and methodological issues. Evaluation Review. 2001;25:113–161. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kusher H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, West SG. Putting the individual back into individual growth curves. PsychologicalMethods. 2000;5:23–43. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Manual for Form-90: A structured assessment interview for drinking and related behaviors. Vol. 5. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1996. Project MATCH Monograph Series. [Google Scholar]

- Rydell RJ, Hugenberg K, Ray D, Mackie DM. Implicit theories about groups and stereotyping: The role of group entitativity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:549–558. doi: 10.1177/0146167206296956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydell RJ, McConnell AR. Perceptions of entitativity and attitude change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:99–110. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C, Xie L, Blum E, Tucker J. Agreement between prospective interactive voice response telephone reporting and structured recall reports of risk behaviors in rural substance users living with HIV/AIDS. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:185–190. doi: 10.1037/a0022725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe E, Saxe L. Community-based substance abuse reduction and the gap between treatment need and treatment utilization: Analysis of data from the “Fighting Back” General Population Survey. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Waters JA, Fazio SL, Hernandez L, Segarra J. The Story of CURA, a Hispanic/Latino Drug Therapeutic Community. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2002;1:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Winn KL, Young W. Predictors of attrition from an outpatient chemical dependency program. Substance Abuse. 1998;19:49. doi: 10.1080/08897079809511374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]