Abstract

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), which affect over 1% of the population, has increased twofold in recent years. Reduced expression of GABAA receptors has been observed in postmortem brain tissue and neuroimaging of individuals with ASDs. We found that deletion of the gene for the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor caused robust autism‐like behaviors in mice, including reduced social contacts and vocalizations. Screening of human exome sequencing data from 396 ASD subjects revealed potential missense mutations in GABRA5 and in RDX, the gene for the α5GABAA receptor‐anchoring protein radixin, further supporting a α5GABAA receptor deficiency in ASDs.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are complex neurodevelopmental conditions that are characterized by impaired social interactions, deficits in communication, repetitive behaviors, and reduced executive function.1 ASDs occur in approximately 1 in every 68 children in the United States and 30% of cases are associated with genetic causes.2, 3, 4 Duplication of the q11.2–13 region on chromosome 15 is the most common duplication copy number variant associated with ASDs. Deletions of this region of the chromosome cause the neurodevelopmental disorders including Angelman syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome.5, 6 In humans, the q11.2–13 region of chromosome 15 contains genes that encode the α5, β3, and γ3 subunits of the γ‐aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor, as well as the ubiquitin protein ligase E3a.

Several lines of evidence have implicated α5 subunit‐containing GABAA receptors in ASDs. Postmortem analyses of brain tissue of individuals with ASDs have revealed reduced levels of both mRNA and protein for several GABAA receptor subtypes including α5 and β3 subunits.7, 8, 9 Positron emission tomography studies have shown reduced binding of an α5GABAA receptor‐selective ligand in the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, brain regions that mediate social interaction and reward behaviors.10 Despite such compelling evidence, it remains uncertain whether reduced expression of α5GABAA receptors contributes to the behavioral symptoms of ASDs.

The activity of GABAA receptors is modified by proteins that regulate the trafficking and anchoring of GABAA receptors to the plasma membrane. The anchoring of α5GABAA receptors at extrasynaptic regions of neurons is regulated by the cytosolic protein radixin.11 The role of radixin in ASDs has not been studied; however, exon deletions in the gene that encodes gephyrin, another GABAA receptor‐anchoring protein, have been linked to autism, schizophrenia, and seizures.12

Here, we studied whether deletion of the gene that encodes the α5 subunit (Gabra5−/−) in mice causes an autism‐like behavioral phenotype. We also examined exome sequencing data from 396 human subjects to determine whether rare coding variants in the GABRA5 gene or the radixin (RDX) gene were associated with autism.

Materials and Methods

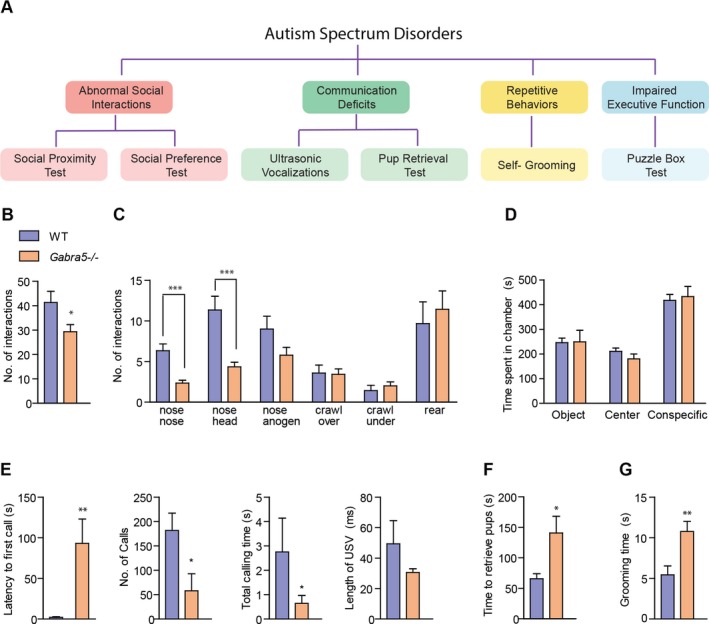

Experimental animals

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Toronto and were performed in accordance with guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Gabra5 −/− mice were generated using a C57BL/6J and Sv129Ev background, as described previously.13 Male mice were used for all the behavioral assays except the measurements of ultrasonic vocalizations and pup retrieval. For these experiments, pups of both sexes were used and dams performed the pup retrieval. Age‐matched 3‐ to 5‐month‐old mice were used to study social interaction, social preference, grooming, and executive function. Ultrasonic vocalization was measured on postnatal days 6–8. In the pup retrieval assay, the dams were greater than 3 months of age and studies were performed at postnatal days 6–8. Behavioral tests that have been previously used to study autism‐like behaviors in mice were performed (Fig. 1A),14 as described in Data S1.

Figure 1.

Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit fewer social contacts, reduced ultrasonic vocalizations, increased latency to retrieve pups, and increased self‐grooming. (A) Core features of autism and behavioral tests used to assess autism‐like deficits in mice. (B) Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit fewer total contacts with a conspecific during the social proximity test. Student's t‐test; WT, n = 12, Gabra5 −/−, n = 14; *P < 0.05. (C) Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit fewer nose‐to‐nose and nose‐to‐head contacts. Student's t‐test; WT, n = 12, Gabra5 −/−, n = 14; ***P < 0.0001. WT and Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit a similar number of nose‐to‐anogenital (P = 0.084), crawl over (P = 0.849), crawl under (P = 0.477), and rearing (P = 0.616) contacts. Student's t‐tests, n = 12–14. (D) In the three‐chamber social preference test, both Gabra5 −/− and WT mice spent a greater amount of time in the chamber with a conspecific than in the chamber with a novel object. Two‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA); effect of chamber, P < 0.05; effect of genotype, P = 0.815; effect of interaction, P = 0.882. (E) Ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) in neonatal pups separated from the dam (WT, n = 8, Gabra5 −/− n = 7). The latency to emit the first USV was increased in Gabra5 −/− mice compared to WT mice. Student's t‐test; **P < 0.01. Gabra5 −/− emit fewer USVs over 4 min than WT mice. Student's t‐test; *P < 0.05. The time spent emitting USVs during the first minute of observation is reduced in Gabra5 −/− mice. Mann–Whitney U test; *P < 0.05. The average length of an individual USV was similar between WT and Gabra5 −/− mice. Student's t‐test; P = 0.274. (F) Time for dams to retrieve pups to the nest was greater in Gabra5 −/− mice than WT mice. Student's t‐test; WT, n = 9, Gabra5 −/− n = 10; *P < 0.05. (G) Gabra5 −/− spend more time self‐grooming than WT mice during a 10 min test period. Student's t‐ test; WT, n = 9, Gabra5 −/− n = 9; **P < 0.01. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Exome data from human probands

The coding sequences of GABRA5 (on human chromosome 15) and RDX (on chromosome 11) were examined for coding sequence variants. Next‐generation exome sequencing data from 396 Canadian ASD probands was used to detect potential sequence variants, as previously described12 (see also Data S1). All subjects and/or parents consented to the study, which was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Hospital for Sick Children. Following a general protocol that was similar to those used in previous studies,4 rare variants were defined as those with a frequency of less than 1% in population databases (The 1000 Genomes Project, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project and the Exome Aggregation Consortium).15 All novel or rare nonsynonymous variants were validated using Sanger sequencing. Damaging missense single‐nucleotide variants were defined as those predicted to be functionally damaging by SIFT and PolyPhen‐2 prediction software.

Results

Reduced social contact is a common behavioral feature of ASDs. To study social contact, the social proximity assay was used to measure interactions between a test mouse and a conspecific.16 Gabra5 −/− mice exhibited significantly fewer social contacts than wild‐type (WT) mice (t (24) = 2.28, P = 0.031 Fig. 1B). The numbers of nose‐to‐nose (t (24) = 4.68, P < 0.0001) and nose‐to‐head (t (24) = 4.14, P < 0.001) contacts were reduced in Gabra5 −/− mice. Other forms of social contact were similar between the genotypes (Fig. 1C).

Next, preference for social stimuli was assessed using the three‐chamber social approach test.17 During the habituation phase of the study, WT and Gabra5 −/− mice spent equal time in the left and right chambers, indicating no inherent preference (genotype: F 1,72 = 0.0, P = 1.0; interaction: F 2,72 = 0.758, P = 0.472; center chamber: WT 148.0 ± 9.36 sec vs. Gabra5 −/− 133.58 ± 10.95 sec; left chamber: WT 364.29 ± 11.33 sec vs. Gabra5 −/− 372.75 ± 11.40 sec; right chamber: WT 387.71 ± 8.63 sec vs. Gabra5 −/− 393.67 ± 9.07 sec). During the testing phase, WT and Gabra5 −/− mice spent more time in the chamber that contained the conspecific. Thus, both genotypes exhibited a normal social preference in this test (chamber: F 2,72 = 34.85, P < 0.0001; genotype: F 1,72 = 0.02, P = 0.815; interaction: F 2,72 = 0.33, P = 0.716; Fig. 1D).

To assess communication, we measured ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) that were emitted by neonatal pups that had been separated from the dam.18, 19 The latency to emit the first USV was increased in Gabra5 −/− mice relative to WTs (t (13) = 3.27, P = 0.006; Fig. 1E). The total number of calls was reduced in Gabra5 −/− mice (t (13) = 2.47, P = 0.029; Fig. 1E). In addition, the emitting time recorded during the first minute of separation was reduced in Gabra5 −/− mice compared to WT mice, demonstrating a reduction in vocalization (Mann–Whitney U = 10.0, P = 0.04; Fig. 1E). The average length of individual USVs was no different between groups (t (13) = 1.14, P = 0.274; Fig. 1E).

To determine whether there were functional implications of the reduced USVs, the time required for the dams to retrieve five pups to the nest following the 3‐min separation period was measured. The latency to retrieval was increased in Gabra5 −/− dams relative to WT dams (t (17) = 2.49, P = 0.024; Fig. 1F).

Next, repetitive behaviors, which are a common feature of ASDs, were studied. Such unusually long periods of self‐grooming in mice are considered to be a spontaneous form of motor stereotypy.20 Gabra5 −/− mice spent more time self‐grooming than WT mice during a 10‐min observation period (t (16) = 3.25, P = 0.005; Fig. 1G).

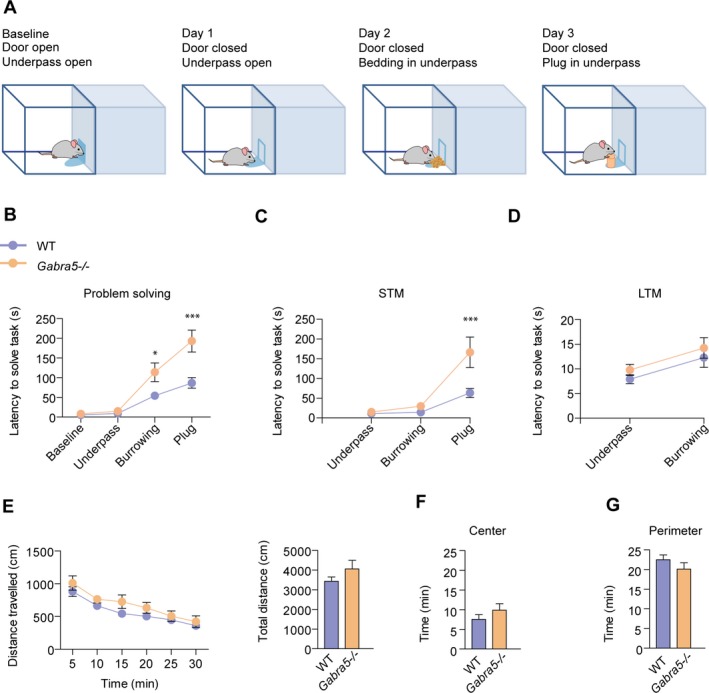

Executive function, which refers to problem solving and cognitive flexibility, is often impaired in ASDs.21 Executive function was assessed with the puzzle box. In this assay, mice were presented with progressively more difficult tasks to reach the goal (darkened) box (Fig. 2A).22 Relative to WT mice, Gabra5 −/− mice required more time to reach the goal box and thus exhibited impaired performance on the first exposure to a new challenge that required burrowing (Tukey's post hoc P < 0.05) and for the removal of a plug that obstructed the underpass (post hoc test P < 0.001, genotype F 1,68 = 20.31, P < 0.0001; interaction F 3,68 = 6.56, P < 0.001; Fig. 2B). Short‐term memory, an important element of executive function, was assessed by retesting the mice 2 min after the first exposure to the task. Latency for the plug task was longer in Gabra5 −/− mice (genotype F 1,51 = 9.91, P = 0.003; interaction F 2,51 = 5.75, P = 0.006; post hoc test P < 0.001; Fig. 2C). Long‐term memory tested 24 h after the first exposure to both the underpass and burrowing tasks was not impaired in Gabra5 −/− mice (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Executive function is impaired in Gabra5 −/− mice. (A) Schematic of the puzzle box test. (B) Gabra5 −/− mice and WT mice exhibited a similar latency at baseline, to enter the goal box through the open door and a similar latency on day 1, when they were required to use the underpass to enter the goal box. Gabra5 −/− exhibited a longer latency than WT mice to burrow through bedding on day 2, or remove a cardboard plug on day 3 to gain access to the goal box. Two‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA); n = 9–10; effect of genotype, P < 0.0001; effect of trial, P < 0.0001; effect of interaction, P < 0.001. Tukey's HSD post hoc test; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (C) Short‐term memory (STM) on the puzzle box test, tested 2 min after first exposure to the task. Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit impaired short‐term memory and a longer latency to complete the short‐term memory plug task. Two‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA); n = 9–10; effect of genotype, P < 0.01; effect of trial, P < 0.0001; effect of interaction, P < 0.05; Tukey's HSD post hoc test, **P < 0.001. (D) Long‐term memory (LTM) on the puzzle box test, tested 24 h after first exposure to the task. Gabra5 −/− and WT mice exhibit similar performance on the underpass and burrowing long‐term memory tasks. Two‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA); n = 9–10; effect of genotype, P = 0.238; effect of trial, P < 0.01; effect of interaction, P = 0.979. (E–G) Performance of WT and Gabra5 −/− mice in the open‐field test. (E) Gabra5 −/− and WT mice exhibited a similar distance travelled in the open‐field test over a 30‐min test period. Gabra5 −/− and WT mice spent a similar amount of time in the center (F) and perimeter (G) regions of the open field. Student's t‐test; n = 10. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

In the open‐field test, no differences were observed between WT and Gabra5 −/− mice (Fig. 2E–G) suggesting normal locomotion and anxiety in Gabra5 −/− mice.

Mutations in GABRA5 and RDX in ASD probands

De novo and rare inherited sequence‐level variants have been shown to contribute to ASD risk.21, 23 Consequently, the coding sequences of GABRA5 and RDX were screened for coding sequence variation using next‐generation exome sequencing data from a cohort of 396 Canadian ASD probands. Two rare missense coding variants were identified in GABRA5, each in a single male ASD case. One of the variants was predicted to be functionally damaging as indicated by both PolyPhen‐2 and SIFT prediction software (Table 1). Four missense coding variants were identified in RDX. One of the variants (hg 19 chr11:110,104,062) was present in three male probands, whereas the remaining variants were present in single ASD cases, two male and one female. Two of the variants in RDX were predicted to be functionally damaging.

Table 1.

Missense mutations in Gabra5 and Rdx in ASD probands

| Gene | Position | Proband | Codon change | Substitution | Inheritance | PolyPhen‐2 prediction | SIFT prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABRA5 | chr15:27,182,361 | 1M | Gtc/Atc | V204I | Maternal | 0.005 benign | 0.41 tolerated |

| GABRA5 | chr15:27,128,545 | 1M | gGg/gCg | G113A | Maternal | 0.991 probably damaging | 0.04 damaging |

| RDX | chr11:110,104,002 | 1M | aCc/aTc | T516I | Paternal | 0.998 probably damaging | 0.02 damaging |

| RDX | chr11:110,104,138 | 1M | Cct/Act | P471T | Maternal | 0.585 possibly damaging | 0.51 tolerated |

| RDX | chr11:110,128,601 | 1F | Gat/Cat | D197H | Heterozygous in both | 0.999 probably damaging | 0.0 damaging |

| RDX | chr11:110,104,062 | 3M | gCt/gTt | A496V |

1 Paternal 2 Maternal |

0.999 probably damaging | 0.52 tolerated |

The position of the mutation, the sex of the proband (M, male; F, female), the specific codon change, the resultant amino acid substitution, and the inheritance (maternal, paternal, or both) are listed. The prediction scores generated by PolyPhen‐2 and SIFT software are listed for each mutation. A PolyPhen‐2 score <0.5 denotes a mutation that is predicted to be benign, a score >0.5 denotes a mutation that is probably damaging, and a score = 1 denotes a mutation that is predicted to be damaging. A SIFT score <0.05 denotes a damaging mutation and a score >0.05 denotes a tolerated mutation.

Discussion

Global deletion of the Gabra5 gene causes autism‐like behaviors that are similar to those observed in other ASD mouse models, including the Tuberous sclerosis 1 mouse, the Shank1 null‐mutant mouse, and inbred BTBR T+tf/J mice.16, 18, 19, 20 Having identified a behavioral phenotype in Gabra5 −/− mice, we sought to determine whether pathogenic variants in GABRA5 or RDX might be found in human subjects with ASD. From a cohort of 396 cases analyzed by exome sequencing, we identified six rare missense variants (<1% frequency in population databases). Three of these missense mutations were predicted to damage protein function. RDX encodes the anchoring protein radixin and damaging coding variants are predicted to decrease the number of α5GABAA receptors at extrasynaptic sites. Although rare missense coding variants of RDX have not been previously reported in ASD cases, exonic deletions of the GABAA receptor‐anchoring protein gephyrin have been associated with psychiatric conditions, including autism.12 It remains to be determined whether the variants identified in this study contribute to ASD cases.

Individuals with autism frequently exhibit problems with learning and memory. Results from this study showed that Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit deficits in short‐term memory but only when the task became increasingly more difficult (i.e., the plug task). In contrast, no long‐term memory deficits were observed in the Gabra5 −/− mice. These experimental results are consistent with previous reports that show deficits depend on cognitive domain and demand of the task. For example, memory performance of Gabra5 −/− mice is unimpaired for contextual fear memory, cued fear conditioning and novel object recognition.24, 25 However, selective knockdown of Gabra5 in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus caused impaired performance when mice were required to distinguish between an aversive context and a similar safe context.26 Reversal learning in the Morris Water Maze task was also impaired in these mice.26 Interestingly, Gabra5 −/− mice show improved performance for trace fear conditioning and the Morris water maze compared with WT mice.13, 24 Thus, only certain learning and memory tasks are vulnerable to reduced expression levels of α5GABAA receptors.

The role of α5GABAA receptors in memory formation is further supported by previous studies of long‐term potentiation (LTP) of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus.24 LTP is widely considered to be a network substrate of memory and α5GABAA receptors set the level of stimulation that is required to induce LTP in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus.24 Specifically, stimulation of Schaffer collaterals at a low frequency (10 Hz) elicits long‐term depression of excitatory transmission in slices from wild‐type mice, whereas the same level of stimulation elicits LTP in Gabra5 −/− slices. Thus, α5GABAA receptors set the threshold for stimulating LTP and may therefore be involved in memory formation.24 Consistent with the above findings, a current theory suggests that autism‐like behaviors result from an increase in the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmission (E/I) in the brain.27 The autism‐like behaviors observed in Gabra5 −/− mice may result from an increased E/I ratio. Indeed, Gabra5 −/− mice exhibit a reduced tonic inhibitory conductance and increased excitability of principal neurons in the hippocampus.28 In other brain regions, this increase in neuronal excitability may lead to autism‐like behavioral deficits. Even transient depolarization of neurons using optogenetic techniques in the medial prefrontal cortex causes deficits in social behavior, and concomitant photostimulation of inhibitory, GABAergic neurons partially reverses these deficits.29 Similarly, treatment with a drug that increases GABAA receptor function reverses abnormal social behavior in the Scn1a+/− mouse model of autism.30

The results from the current study suggest that drugs that act as positive allosteric modulators of α5GABAA receptors may ameliorate autism‐like behaviors.31, 32 Certain positive allosteric modulators that reverse deficits in spatial memory in aged rats and locomotor hyperactivity in a mouse model of schizophrenia may reduce autism‐like behavioral deficits.31, 32

Finally, reduced expression and function of GABRA5 and RDX may cause neurodevelopmental changes that contribute to ASD‐like behavior. In future studies, it will be of interest to determine whether clinical disorders (e.g., seizures or cognitive defects) are observed in individuals with mutations of GABRA5 or RDX genes. Such an association would further strengthen the E/I hypothesis of autism. In summary, our results show that reduced expression of α5GABAA receptors contributes to autism‐like behaviors in mice and potentially damaging mutations of GABRA5 and RDX occur in ASD cases.

Author Contributions

A. A. Z. conceived and designed the study, acquired and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript and figures. S. W. P. K. acquired and analyzed the data and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. Z. A. acquired and analyzed the data. S. W. acquired and analyzed the data and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. M. M., A. J. M., and E. S. contributed to the study design and drafting of the manuscript. S. W. S. contributed to the study design, data, and drafting of the manuscript. B. A. O. contributed to the study design and drafting of the manuscript and figures.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Data S1. Detailed Methods

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ella Czerwinska, Nathan Chan, and Joanna Dida and The Centre for Applied Genomics for their expert technical assistance.

References

- 1. Anagnostou E, Zwaigenbaum L, Szatmari P, et al. Autism spectrum disorder: advances in evidence‐based practice. CMAJ 2014;186:509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wingate M, Kirby RS, Pettygrove S, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years ‐ autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014;63:21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jiang YH, Yuen RK, Jin X, et al. Detection of clinically relevant genetic variants in autism spectrum disorder by whole‐genome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:249–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tammimies K, Marshall CR, Walker S, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of chromosomal microarray analysis and whole‐exome sequencing in children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA 2015;314:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moreno‐De‐Luca D, Sanders SJ, Willsey AJ, et al. Using large clinical data sets to infer pathogenicity for rare copy number variants in autism cohorts. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:1090–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hogart A, Wu D, LaSalle JM, Schanen NC. The comorbidity of autism with the genomic disorders of chromosome 15q11.2–q13. Neurobiol Dis 2008;38:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, et al. mRNA and protein levels for GABAA α4, α5, β1 and GABABR1 receptors are altered in brains from subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2010;40:743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blatt GJ, Fitzgerald CM, Guptill JT, et al. Density and distribution of hippocampal neurotransmitter receptors in autism: an autoradiographic study. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. GABAA receptor downregulation in brains of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2009;39:223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mendez MA, Horder J, Myers J, et al. The brain GABA‐benzodiazepine receptor α5 subtype in autism spectrum disorder: a pilot [(11)C]Ro15‐4513 positron emission tomography study. Neuropharmacology 2013;68:195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loebrich S, Bahring R, Katsuno T, et al. Activated radixin is essential for GABAA receptor α5 subunit anchoring at the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO J 2006;25:987–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lionel AC, Vaags AK, Sato D, et al. Rare exonic deletions implicate the synaptic organizer Gephyrin (GPHN) in risk for autism, schizophrenia and seizures. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collinson N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, et al. Enhanced learning and memory and altered GABAergic synaptic transmission in mice lacking the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci 2002;22:5572–5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silverman JL, Yang M, Lord C, Crawley JN. Behavioural phenotyping assays for mouse models of autism. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Genomes Project . C. A map of human genome variation from population scale sequencing. Nature 2010;467:1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Defensor EB, Pearson BL, Pobbe RL, et al. A novel social proximity test suggests patterns of social avoidance and gaze aversion‐like behavior in BTBR T+ tf/J mice. Behav Brain Res 2011;217:302–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic‐like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav 2004;3:287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wohr M, Roullet FI, Hung AY, et al. Communication impairments in mice lacking Shank1: reduced levels of ultrasonic vocalizations and scent marking behavior. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e20631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young DM, Schenk AK, Yang SB, et al. Altered ultrasonic vocalizations in a tuberous sclerosis mouse model of autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:11074–11079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsai PT, Hull C, Chu Y, et al. Autistic‐like behaviour and cerebellar dysfunction in Purkinje cell Tsc1 mutant mice. Nature 2012;488:647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuen RKC, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Merico D, et al. Whole‐genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat Med 2014;21:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ben Abdallah NM, Fuss J, Trusel M, et al. The puzzle box as a simple and efficient behavioral test for exploring impairments of general cognition and executive functions in mouse models of schizophrenia. Exp Neurol 2011;227:42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional, and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 2014;515:209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin LJ, Zurek AA, MacDonald JF, et al. α5GABAA receptor activity sets the threshold for long‐term potentiation and constrains hippocampus‐dependent memory. J Neurosci 2010;30:5269–5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zurek AA, Bridgwater EM, Orser BA. Inhibition of α5 γ‐Aminobutyric acid type A receptors restores recognition memory after general anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2012;114:845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Engin E, Zarnowska ED, Benke D, et al. Tonic inhibitory control of dentate gyrus granule cells by α5‐containing GABAA receptors reduces memory interference. J Neurosci 2015;35:13698–13712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav 2003;2:255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonin RP, Martin LJ, Macdonald JF, Orser BA. α5GABAA receptors regulate the intrinsic excitability of mouse hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol 2007;98:2244–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 2011;477:171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han S, Tai C, Westenbroek RE, et al. Autistic behavior in Scn1a(+/−) mice and rescue by enhanced GABAergic transmission. Nature 2012;489:385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gill KM, Lodge DJ, Cook JM, et al. A novel α5GABAAR‐positive allosteric modulator reverses hyperactivation of the dopamine system in the MAM model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011;36:1903–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koh MT, Rosenzweig‐Lipson S, Gallagher M. Selective GABAA α5 positive allosteric modulators improve cognitive function in aged rats with memory impairment. Neuropharmacology 2013;64:145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Detailed Methods