SUMMARY

SETTING

A referral hospital for tuberculosis (TB) in Irkutsk, the Russian Federation.

OBJECTIVE

To describe disease characteristics, treatment and hospital outcomes of TB-HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

DESIGN

Observational cohort of HIV-infected patients admitted for anti-tuberculosis treatment over 6 months.

RESULTS

A total of 98 patients were enrolled with a median CD4 count of 147 cells/mm3 and viral load of 205 943 copies/ml. Among patients with drug susceptibility testing (DST) results, 29 (64%) were multidrug-resistant (MDR), including 12 without previous anti-tuberculosis treatment. Nineteen patients were on antiretroviral therapy (ART) at admission, and 10 (13% ART-naïve) were started during hospitalization. Barriers to timely ART initiation included death, in-patient treatment interruption, and patient refusal. Of 96 evaluable patients, 21 (22%) died, 14 (15%) interrupted treatment, and 10 (10%) showed no microbiological or radiographic improvement. Patients with a cavitary chest X-ray (aOR 7.4, 95%CI 2.3–23.7, P = 0.001) or central nervous system disease (aOR 6.5, 95%CI 1.2–36.1, P=0.03) were more likely to have one of these poor outcomes.

CONCLUSION

High rates of MDR-TB, treatment interruption and death were found in an HIV-infected population hospitalized in Irkutsk. There are opportunities for integration of HIV and TB services to overcome barriers to timely ART initiation, increase the use of anti-tuberculosis regimens informed by second-line DST, and strengthen out-patient diagnosis and treatment networks.

Keywords: multidrug-resistant TB, Russian Federation, extensively drug-resistant TB, human immunodeficiency virus, injection drug use

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV) is more common in the Irkutsk oblast of Eastern Siberia than all other regions in the Russian Federation.1 HIV positivity has been estimated to be as high as 57% among randomly sampled patients with injection drug use (IDU) in Irkutsk City.2 Recent co-prevalence surveillance suggests that nearly one in four new tuberculosis (TB) patients is HIV-infected in Irkutsk.3 Annual HIV-TB incidence has increased from approximately 5 per 100 000 population in 2007 to 26/ 100 000 in 2014.3 Despite the growing HIV-TB burden in Irkutsk, integration of HIV and TB services has been slow; for example, TB physicians are restricted from prescribing antiretroviral therapy (ART).4

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB, defined as resistance to at least isoniazid [INH] and rifampin [RMP]) also complicates HIV-TB treatment in Irkutsk. In a previous retrospective examination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from the region, 25% of patients without previous treatment had MDR-TB.5 In Tomsk, Siberia, through a recent multidisciplinary effort to individualize MDR-TB treatment, relatively high rates of favorable treatment outcomes were reported.6 However, these patients were largely non-HIV-infected, and anti-tuberculosis treatment had been applied in an algorithmic approach based on expanded drug susceptibility testing (DST) results. The potential utility of such an approach within the HIV-infected population of Irkutsk has not been studied.

We enrolled HIV-infected patients presenting for anti-tuberculosis treatment to examine M. tuberculosis drug resistance and patterns of anti-tuberculosis drug and ART prescription in relation to outcomes of anti-tuberculosis treatment. An interim analysis found that ART initiation was less frequent than anticipated. We reoriented the study to understand this observation, describe the interventions to improve ART initiation, and report on short-term in-patient TB outcomes.

STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS

Subjects and study site

Patients were recruited on admission to the Irkutsk TB Dispensary in Irkutsk City, the largest regional TB hospital, which is responsible for the treatment of TB in HIV-infected patients. Patients are referred from clinics or non-TB hospitals based on symptoms or screening chest fluorography, which regional guidelines recommend annually in all adults, and twice per year in patients with HIV infection. Subjects were eligible if aged ≥15 years, HIV-positive on immunoassay and confirmatory Western blot, and being initiated on anti-tuberculosis treatment. Patients were enrolled from February to August 2014.

All subjects provided written informed consent. The protocols were approved jointly by the Scientific Centre for Family Health and Human Reproduction Problems, Irkutsk, Russian Federation (a Federal State Public Scientific Institution), and the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Procedures and definitions

Shortly after admission, research staff interviewed the patients and gathered additional data from their charts to record basic demographics and comorbidities, HIV and TB treatment history, CD4 count (Cell Lab Quanta SC, Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, CA, USA) and HIV-1 viral load (Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor version 1.5, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA) at presentation, chest radiographic (CXR) findings, available M. tuberculosis DST results, and the initial medication regimen. Duration of ART before presentation was not assessed. CXR was defined as ‘cavitary’ if any cavity was noted regardless of other abnormality, ‘miliary’ if exclusively miliary, or ‘other’ if it contained any other infiltrative pattern, abnormal intrathoracic lymphadenopathy or pleural abnormality.

Initial in-patient anti-tuberculosis drug regimens were recorded according to Russian Federation categories: Categories I and IIa include first-line drugs only, and Categories IIb or IV include second-line drugs for suspected drug resistance (IIb) or confirmed MDR-TB (IV).7 The patient charts were then revisited approximately monthly to record the final medication regimen and disposition, including transfer/discharge, treatment interruption, or death.

Regional standards of care were for patients to remain hospitalized for the entire duration of the intensive phase of treatment, from 2 months for drug-susceptible TB to 8 months for MDR-TB; however, this varied depending upon the extent of disease and response to treatment. Any subject leaving the hospital against medical advice was defined as having treatment interruption, although some may ultimately have completed treatment in another setting. Subjects were defined as having a favorable outcome at the end of the in-patient phase if they were discharged home or transferred to another treatment facility with improved symptoms and, if applicable, CXR improvement (e.g., cavity closure) and/or microbiological improvement (culture negativity if pretreatment sputum culture was positive).

Mycobacterial culture and DST were performed according to hospital routine at the discretion of the treating clinician. Submitted specimens were cultured on Löwenstein-Jensen slants and identified as M. tuberculosis complex.8 DST was typically performed for the following drugs using the absolute concentration method on agar slants: RMP (critical concentration 40 μg/ml), INH (1 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml), ethambutol (2 μg/ml), streptomycin (10 μg/ml), ofloxacin (OFX) (2 μg/ml), kanamycin (KM) (30 μg/ml) and ethionamide (30 μg/ml). A subset of isolates also underwent minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing against 12 first- and second-line anti-tuberculosis medications using the commercial microtiter plate, Sensititre MYCOTB (TREK Diagnostics, Cleveland, OH, USA).9

Statistical methods

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel, version 14.1.3 (MicroSoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using SPSS, version 22 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Armonk, NY, USA). For the subset of M. tuberculosis isolates with MIC testing, susceptibility was determined by an MIC value at or below the critical concentration using the agar proportion method,10 and the χ2 test was used to compare the proportion susceptible between drugs of the same class. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the median number of susceptible drugs identified by MIC testing between patients with and without MDR-TB. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine risk factors for a poor outcome, defined as death, treatment interruption, failure of CXR improvement, or failure to culture convert to negative. Multivariate regression included any variable with P < 0.10 on univariate analysis.

RESULTS

Of 103 HIV-infected patients enrolled, two were excluded due to incomplete admission data and three due to infection with non-tuberculous mycobacteria; 98 patients were fully analyzed (mean age 34 ± 6.7 years, 64 [65%] males) (Table 1). The median CD4 count was 147 cells/mm3 (interquartile range [IQR] 45–256) and 19 (19%) patients were on ART before admission; however, only two had a viral load of ≤20 copies/ml (2% of the total population).

Table 1.

Admission demographics, comorbidities and disease characteristics (n = 98)

| Characteristic | Result, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 34 ± 6.7 |

| Male sex | 64 (65) |

| CD4, cells/mm3, median [IQR] | 147 [45–256] |

| HIV viral load, median [IQR] | 205 943 [43 250–685 000] |

| ART before admission | 19 (19)* |

| Self-reported diabetes | 1 (1) |

| Prior incarceration | 29 (30) |

| History of IDU | 42 (43) |

| Cigarette smoking | 75 (77) |

| Fluorography screened in the previous year | 75 (77) |

| If fluorography screened, proportion abnormal (% screened) | 70 (93) |

| Screened using Xpert® MTB/RIF | 37 (38) |

| If Xpert screened, proportion positive (% screened) | 14 (38) |

| BCG vaccinated | |

| >5 years ago | 95 (97) |

| >1 year but ≤5 years ago | 0 |

| <1 year ago | 0 |

| Unknown | 3 (3) |

| Previous course of anti-tuberculosis treatment | |

| None | 49 (50) |

| 1 | 26 (27) |

| >1 | 22 (22) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) |

| Previous treatment with any second-line anti-tuberculosis drug | 12 (12) |

| Duration of symptoms before admission, days, mean ± SD | 57 ± 55.1 (maximum 300) |

| Anatomic site (% total)† | |

| Pulmonary | 92 (94) |

| Pleuritis | 22 (22) |

| CNS | 11 (11) |

| Lymph node | 9 (9) |

| Bone/joint | 7 (7) |

| Abdominal | 6 (6) |

| Genito-urinary | 3 (3) |

| Not specified | 4 (4) |

| Chest X-ray abnormality (% of pulmonary TB) | |

| Cavitary | 25 (26) |

| Miliary | 34 (35) |

| Other | 39 (40) |

Only 2 cases with viral load ≤20 copies.

2 cases of pleuritis did not have concurrent pulmonary disease, but all other cases of extra-pulmonary TB also had pulmonary disease. All cases of non-specified anatomic site had abnormal chest X-ray.

SD =standard deviation; IQR =interquartile range; HIV =human immunodeficiency virus; ART =antiretroviral therapy; IDU = intravenous drug use; BCG = bacille Calmette-Guérin; CNS = central nervous system.

M. tuberculosis drug resistance patterns using conventional DST

Among the 98 patients, 20 (21%) did not have a retrievable culture or DST performed, 31 (32%) underwent at least one attempt at culture but the results were negative, and 46 had a positive culture, of whom 45 (98%) underwent DST against at least RMP and INH. Of those with culture-positive TB and DST, 37 (82%) were INH-resistant; 29 (64%) were MDR-TB. Among MDR-TB patients, eight (28%) were OFX-resistant, 17 (59%) were resistant to at least one second-line injectable agent, and six (21%) had extensively drug-resistant TB (MDR-TB plus additional resistance to any fluoroquinolone and to at least one second-line injectable). While MDR-TB was more common among patients with previous anti-tuberculosis treatment, 12 MDR-TB patients had had no prior treatment (24% of all primary TB patients and 46% of primary TB patients with DST).

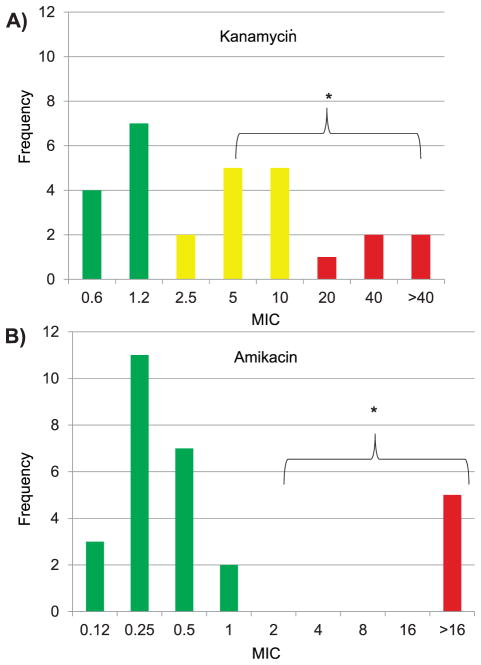

Initial anti-tuberculosis treatment

Prior to DST, a minority of patients were initially prescribed regimens that included only first-line drugs: Category I in 29 (30%) and Category IIa in 17 (17%). More than half initially received a regimen that included second-line drugs: Category IIb in 30 (31%) and Category IV in 22 (22%). The most common initially prescribed anti-tuberculosis drug was high-dose INH (9.7 mg/kg ± 1.3) (Table 2). Following empiric regimen modification or conventional DST, 73% of all subjects were treated with a second-line injectable or a fluoroquinolone. Of the 28 patients whose isolates were MIC tested, 18 had MDR-TB, and the MIC plate identified a median of 5.0 drugs (IQR 4.0–6.0) to which the isolate was susceptible and could reasonably be used in combination. Within-class differences were notable for injectable aminoglycosides, where of the five isolates resistant to amikacin (AMK), all were also KM-resistant; however, of the 23 isolates susceptible to AMK, five (22%) were KM-resistant (P = 0.003) (Figure). Furthermore, based on MIC testing and the initial regimens prescribed, MDR-TB patients were on a median of 2 (IQR 1.0–3.25) active drugs, significantly fewer than those without MDR-TB, who were on a median of 4 active drugs (IQR 3.75–5.0, P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Initial drug regimens and dosing among 98 patients

| Drug* | Number of patients prescribed (% of 98) | Daily dose mg range (mode) |

Mg/kg mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line drugs | |||

| Isoniazid | 75 (77) | 300–800 (600) | 9.7 ± 1.3 |

| Rifampin | 58 (59) | 300–600 (450) | 8.0 ± 1.2 |

| Rifabutin | 11 (11) | 300–450 (300) | 5.7 ± 1.5 |

| Ethambutol | 70 (72) | 600–2000 (1200) | 23.8 ± 3.5 |

| Pyrazinamide | 82 (84) | 500–2000 (1500) | 27.0 ± 4.4 |

| Streptomycin | 22 (22) | 500–1000 (1000) | 15.1 ± 2.4 |

| Fluoroquinolones | |||

| Ciprofloxacin | 11 (11) | 500–1750 (1000) | 16.3 ± 6.0 |

| Ofloxacin | 7 (7) | 200–800 (400) | 7.3 ± 3.6 |

| Levofloxacin | 27 (28) | 500–2000 (500) | 10.5 ± 3.7 |

| Moxifloxacin | 3 (3) | All 400 | 6.6 ± 0.6 |

| Second-line injectables | |||

| Kanamycin | 25 (26) | 500–1000 (1000) | 17.6 ± 3.6 |

| Amikacin | 9 (9) | 500–1000 (1000) | 16.3 ± 4.1 |

| Capreomycin | 15 (15) | 750–1000 (1000) | 16.8 ± 1.3 |

Other anti-tuberculosis drugs given include prothionamide (30%), para-aminosalicylic acid (18%), cycloserine (16%), terizidone (3%) and linezolid (1%).

SD = standard deviation.

Figure.

Comparison of MIC within the class of second-line aminoglycosides by MYCOTB Sensititre (Trek Diagnostics). Green/dark grey = susceptible (MIC ≤2 dilutions below critical concentration using the agar proportion method); yellow/pale grey = borderline susceptible (MIC at or within one dilution of critical concentration); red/black =resistant (MIC more than two dilutions above). No isolate was of borderline susceptibility for amikacin. * P = 0.003 for difference in resistance using critical concentration by agar proportion method as breakpoint.10 This image can be viewed online in color at http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2016/00000020/00000001/art00011.

HIV treatment

Despite a median in-patient stay of 126 days (IQR 78–171), only 10 additional patients were started on ART. This finding was unexpected, and a further retrospective chart review was performed to determine the primary reasons for lack of ART initiation. Of the 79 ART-naïve patients, 78 (99%) had been evaluated by the infectious diseases specialist necessary to initiate ART. Common practice was for at least two evaluations by the specialist if there were circumstances preventing ART initiation. The most common reasons for lack of initiation in the hospital were death, transfer to another hospital or treatment interruption, and patient refusal (Table 3).

Table 3.

ART initiation in 78 ART-naïve patients and reasons for lack of initiation

| Primary reason for lack of initiation | Proportion (% of 78) |

|---|---|

| Treatment interruption or transfer to another facility | 21 (27) |

| Patient refusal | 18 (23) |

| Death or clinical deterioration | 16 (21) |

| Substance abuse | 4 (5) |

| Unknown | 9 (12) |

| Started in-patient ART* | 10 (13) |

The most common ART regimen included two reverse transcriptase inhibitors and either a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor or efavirenz; no patient was given a protease inhibitor concurrently with rifampin.

ART =antiretroviral therapy.

Risk factors for early treatment outcome

Of the 96 patients with outcome data, 51 (53%) were defined as having a favorable outcome at the end of the in-patient phase, 21 (22%) had died, 14 (15%) had interrupted treatment, and 10 (10%) lacked microbiological or CXR improvement. The median time to death was 101 days (IQR 47–125). Among those who died, five (24%) were on ARTat admission and the others did not receive ART before death. For the composite outcome, the CXR pattern on admission, known MDR-TB, and presence of central nervous system (CNS) disease were associated with poor outcomes on univariate analysis (Table 4). On multivariate analysis, patients with poor outcome were more likely to have a cavitary CXR on admission (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.4, 95%CI 2.3–23.7, P = 0.001) and CNS disease (aOR 6.5, 95%CI 1.2–36.1, P = 0.03).

Table 4.

Predictors of poor early treatment outcome on univariate analysis (n = 96)

| Favorable* (n = 51) n (%) |

Poor* (n = 45) n (%) |

OR (95%CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age category, >30 years | 44 (86) | 30 (67) | 0.51 (0.21–1.2) | 0.13 |

| Female sex | 17 (33) | 17 (38) | 1.2 (0.53–2.8) | 0.65 |

| CD4, cells/mm3, median [IQR] | 110 [39–200] | 148 [74–326] | NA | 0.76 |

| Previous anti-tuberculosis treatment | 22 (43) | 25 (56) | 1.6 (0.73–3.7) | 0.23 |

| History of IDU† | 21 (42)† | 19 (42) | 1.0 (0.45–2.3) | 0.98 |

| Previous incarceration | 12 (24) | 16 (36) | 1.8 (0.74–4.4) | 0.20 |

| CXR | ||||

| Cavitary | 7 (14) | 18 (40) | 6.9 (2.2–21.6) | 0.001 |

| Miliary | 17 (33) | 17 (38) | 2.7 (1.0–7.3) | 0.05 |

| Other | 27 (53) | 10 (22) | Referent | |

| CNS disease site | 2 (4) | 9 (20) | 6.1 (1.2–30.1) | 0.03 |

| Known MDR-TB‡ | 12 (24) | 18 (40) | 2.2 (0.89–5.2) | 0.09 |

| ART on admission | 9 (18) | 9 (20) | 1.2 (0.42–3.3) | 0.77 |

Favorable = clinical improvement at discharge/transfer plus CXR improvement (e.g., cavity closure on CXR) and sputum culture conversion (if culture-positive at admission); poor =death, lack of CXR improvement, lack of sputum culture conversion or treatment interruption.

Data missing in one patient.

Includes pre-XDR- and XDR-TB.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range; IDU = intravenous drug use; IQR = interquartile range; CXR = chest X-ray; CNS = central nervous system; MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; ART = antiretroviral therapy; XDR-TB = extensively drug-resistant TB.

DISCUSSION

Our cohort of HIV-TB patients from a referral hospital in Irkutsk City, Siberia, demonstrates a multifaceted public health problem highlighted by considerable anti-tuberculosis drug resistance and undertreated HIV. MDR-TB was found in more than 60% of those patients with DST results available. Few patients were on ART at admission, and ART was successfully initiated in only 13% of ART-naïve subjects in the in-patient setting. Poor outcomes such as in-patient death and treatment interruption were common, emphasizing both disease severity and programmatic challenges.

Treating HIV–MDR-TB patients has principally been successful in settings with concerted integration of HIV and TB services.11–13 In Irkutsk, however, the HIV and TB services are institutionally and geographically separate, which we believe contributed to the unexpected lack of ART initiation in this cohort. Despite guidelines from the International Standards of Tuberculosis Care Committee14 and the Russian Federation Ministry of Health4 on the timing of ART initiation in HIV-TB patients, current policies limit the execution of such recommendations in Irkutsk. TB clinicians cannot prescribe ART, and ART is dispensed only from the separate HIV services center after review of the patient’s case by the committee. As a consequence of this interim analysis and a previous qualitative study,15 interventions were begun to 1) improve the content of the message about ART initiation given by the consulting infectious diseases specialist and reduce the time between the first and subsequent follow-up evaluations, with the aim of lowering the rate of patient refusal; 2) create a new managerial position within the Irkutsk TB Dispensary specifically to liaise with the HIV services center; 3) reduce the time to action on HIV laboratory results that dictate urgency of ART (e.g., CD4 count and viral load testing currently not performed onsite at Irkutsk TB hospitals); and 4) administratively prioritize referrals for ART from the TB hospitals to hasten committee approval and dispensation of ART.

The severity of immunosuppression on admission for anti-tuberculosis treatment highlights the need for community outreach efforts in detecting and treating HIV at an earlier disease state. Given the high proportion of patients with a history of IDU in this study, integration of HIV and TB diagnostics into organizations caring for those with substance abuse appears warranted.16,17 Such efforts are currently hampered by policies restricting the use of methadone and other opioid replacement therapies in the Russian Federation.

Strengthening of out-patient HIV-TB services may also reduce the rates of treatment interruption, a common occurrence in this HIV-TB in-patient population in Irkutsk. In some settings within the Russian Federation, rates of treatment interruption have been cut to ~5% by fortifying ambulatory social support services (e.g., food parcels, travel reimbursement, psychological counseling),18 while full community-based treatment of HIV–MDR-TB has been accomplished with low rates of treatment interruption in other locations endemic for coinfection.13

Referral patterns directing the sickest of HIV-TB patients and those with previous anti-tuberculosis treatment for admission to the Irkutsk Dispensary may limit the regional generalizability of these treatment outcomes and the reported drug resistance patterns. Although more than half of the MDR-TB isolates were resistant to a second-line injectable agent, the expansive MIC plate revealed an increased number of presumably active drugs compared to the initial prescribed regimens. Study of reinforced initial regimens while awaiting the result of such a quantitative susceptibility panel appears warranted.6,19

This study had several limitations. The lack of follow-up in all subjects once discharged from the in-patient setting limited data on long-term outcomes, including late ART initiation. Furthermore, anti-tuberculosis treatment before admission to the Irkutsk Dispensary may have rendered some attempts at culture and DST negative. In addition, the retrieval of DST results and drugs tested for every isolate was incomplete.

In conclusion, these findings highlight a serious problem of HIV and drug-resistant TB in a region of the world that serves as a metropolitan crossroads for Central Asia, China, and the Russian Federation. Combating this urgent problem requires integration of HIV and TB services to bolster ART coverage, consistent application of anti-tuberculosis regimens based on high-quality DST, and expansion of supportive strategies to curb treatment interruption and strengthen out-patient care networks.

Acknowledgments

The study was partly supported by the US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (R21 AI108521), and a grant from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, Moscow, Russian Federation (13-04-91445).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Federal Research and Methodological Center for Prevention and Control of AIDS. HIV in the Russian Federation. Moscow, Russian Federation: Federal Research and Methodological Center for Prevention and Control of AIDS; 2014. [Accessed October 2015]. http://www.hivrussia.ru/files/spravkaHIV2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobkov A, Kazennova E, Khanina T, et al. An HIV type 1 subtype A strain of low genetic diversity continues to spread among injecting drug users in Russia: a study of the new local outbreaks in Moscow and Irkutsk. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:257–261. doi: 10.1089/088922201750063188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Center for Tuberculosis Monitoring, Ministry of Health, Russian Federation. The epidemiological situation of tuberculosis in the Russian Federation, 2009–2014. Moscow, Russian Federation: MoH; 2015. [Accessed October 2015]. http://www.mednet.ru/images/stories/files/CMT/tb2015.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Russian Federation. The Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, # 951. Moscow, Russian Federation: MoH; 2014. Guidelines to improve the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhdanova S, Heysell SK, Ogarkov O, et al. Primary multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis from two regions in Eastern Siberia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1649–1652. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.121108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velásquez GE, Becerra MC, Gelmanova IY, Pasechnikov AD, Yedilbayev A. Improving outcomes for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: aggressive regimens prevent treatment failure and death. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:9–15. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Russian Federation. Order of the Ministry of Health, Russian Federation, #109. Moscow, Russian Federation: MoH; 2009. Improvement of tuberculosis control in Russian Federation. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Laboratory Initiative. Mycobacteriology laboratory manual. 1. Geneva, Switzerland: Stop TB Partnership; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall L, Jude KP, Clark SL, et al. Evaluation of the Sensititre MycoTB plate for susceptibility testing of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex against first- and second-line agents. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3732–3734. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02048-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, Armstrong DT, Ssengooba W, et al. Sensititre MYCOTB MIC plate for testing Mycobacterium tuberculosis susceptibility to first- and second-line drugs. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;58:11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01209-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. WHO/HTM/TB/2014.08. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seung KJ, Omatayo DB, Keshavjee S, et al. Early outcomes of MDR-TB treatment in a high HIV-prevalence setting in Southern Africa. PLOS ONE. 2009;4:e7186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brust JCM, Shah NS, Scott M, Chaiyachati K, et al. Integrated, home-based treatment for MDR-TB and HIV in rural South Africa: an alternate model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:998–1004. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TB CARE I. International Standards for Tuberculosis Care. 3. The Hague, The Netherlands: TB CARE I; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bobrova N, Sarang A, Stuikyte R, Lezhentsev K. Obstacles in provision of anti-retroviral treatment to drug users in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: a regional overview. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruce RD, Lambdin B, Chang O, et al. Lessons from Tanzania on the integration of HIV and tuberculosis treatments into methadone assisted treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakubowiak WM, Bogorodskaya EM, Borisov ES, Danilova DI, Kourbatova EK. Risk factors associated with default among new pulmonary TB patients and social support in six Russian regions. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heysell SK, Ahmed S, Mazidur SMM, et al. Quantitative second-line drug-susceptibility in patients treated for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Bangladesh: implications for regimen choice. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0116795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]