Abstract

Executive functions are involved in the development of academic skills and are critical for functioning in school settings. The relevance of executive functions to education begins early and continues throughout development, with clear impact on achievement. Diverse efforts increasingly suggest ways in which facilitating development of executive function may be used to improve academic performance. Such interventions seek to alter the trajectory of executive development, which exhibits a protracted course of maturation that stretches into young adulthood. As such, it may be useful to understand how the executive system develops normally and abnormally in order to tailor interventions within educational settings. Here we review recent work investigating the neural basis for executive development during childhood and adolescence.

Introduction

Executive function (EF) is a broad category of cognition, including cognitive control, sustained attention, inhibition, error monitoring, and working memory. Unlike other cognitive domains, the executive system undergoes a protracted period of development that extends into young adulthood. Behavioral studies have suggested that different domains of EF may develop at different rates during this time [1]. These processes are necessary for the normal development of nearly all academic areas including math [2,3] and language [3] skills. The importance of early EF capacity to academic achievement begins as early as preschool [4] and continues throughout adolescence [5]. As such, there has been much interest in methods to facilitate the development of EFs in school settings in an effort to improve academic performance. Accordingly, an understanding of the neural basis of the executive system’s development could help target interventions to facilitate the development of executive function.

Here we review the existing literature regarding brain systems implicated in the development of the executive system and its significance for academic achievement. We first describe recent behavioral and neuroimaging studies regarding the maturation of the executive system from childhood through adolescence. Second, we describe moderating factors that have been shown to affect the course of executive development. Third, we review studies documenting executive dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders, which often begin in adolescence and are associated with poor educational outcomes [6]. Finally, we present examples of educational interventions that have been proposed as ways of facilitating EF development.

Normative development of executive function: behavioral studies

Childhood and adolescence are periods of rapid development of EF. Dajani and Uddin [7] note that different domains of EF develop at various times during development: inhibition and attentional control emerge and develop in early childhood, information processing abilities improve in mid childhood, while cognitive flexibility and goal setting continue to develop into adolescence. For instance, a longitudinal study of young children charting trajectories of inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility found that these processes developed most rapidly during 3–4 years of age [1]. Though cognitive flexibility develops more slowly than inhibitory control [1], age-related improvements in inhibition have been observed through mid-childhood [8]. Attention and working memory (WM) are additional domains of EF that continue to mature throughout adolescence, while other cognitive domains such as spatial memory and verbal memory do not [9].

Normative development of executive function: neuroimaging studies

Though it is clear from behavioral studies that EF matures during childhood and adolescence, neuroimaging studies provide information regarding how neurodevelopmental processes may underlie the improvement in performance. Studies of brain structure, function, and connectivity provide complementary evidence regarding maturation of the executive system. Structural brain imaging studies indicate that grey matter volume increases during childhood and subsequently declines during adolescence, whereas white matter volumes increase throughout development [10]. However, the trajectory of development may be more important in predicting intelligence and EF than cross-sectional measurements [11]. For example, the correlation between prefrontal cortical thickness and IQ is negative in early childhood but becomes positive in late childhood through early adulthood. Additionally, the trajectory of these changes in cortical thickness are more reflective of IQ than cortical thickness itself [11].

More recent studies have examined how changes in cortical thickness of specific brain regions correlate with EF. For example, in healthy older children, cortical grey matter thinning in the inferior frontal gyrus and anterior cingulate cortex is associated with age-related improvements in cognitive control, while thinning in the superior parietal cortex is associated with improvements in working memory [12]. In contrast, a longitudinal study showed that increased rate of cortical thinning in medial cortical regions during development is associated with more executive deficits in adulthood [13].

While age is strongly related to changes in brain structure, this relationship is less robust for functional measures of executive function. In young children, age was found to be correlated with increased lateral PFC recruitment during a working memory task [14]. In addition, cognitive control studies have shown that children with good task performance recruit different prefrontal regions than adults [15]. However, age effects on task-induced activation of executive regions during sustained attention and inhibition are not completely consistent [16–18]. Cognitive control studies have shown that there is a shift from diffuse to focal patterns of activation during development, with increased activation in regions necessary for effective task performance [19,20].

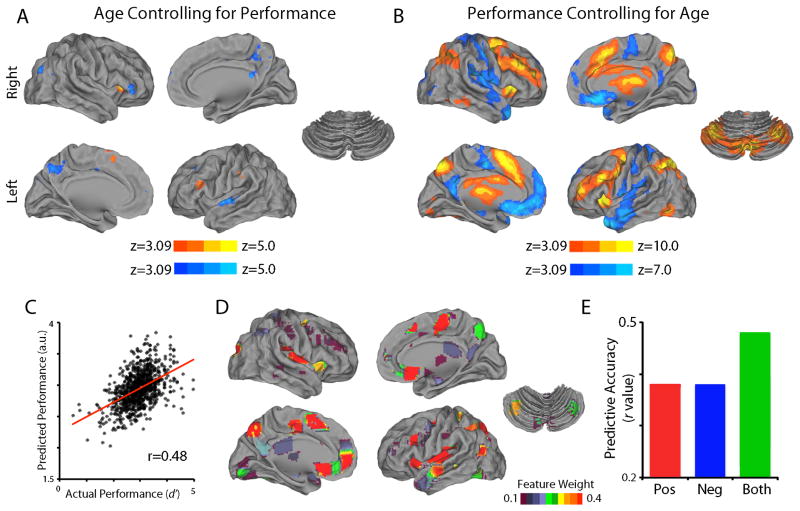

More recently, a large study of 951 youths showed that increased activation of executive regions and reciprocal deactivation of default mode network (DMN) regions underlie the improvements in WM seen during adolescence (see Figure 1). Executive activation and DMN de-activation was more strongly correlated with WM performance than chronological age [21], suggesting that executive development may be understood as a process of functional (rather than chronologic) maturation. Notably, multivariate pattern regression demonstrated that while both executive activation and DMN de-activation could be used to predict performance, maximum accuracy required integration of features from both networks.

Figure 1.

Brain response to WM load is more significantly related to WM performance than subject age. In a sample of 951 youths ages 8–22 imaged as part of the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort using a fractal version of the n-back working memory task, working memory load was associated with executive activation and reciprocal de-activation of non-executive regions including the default mode network (DMN). This pattern of activation was weakly associated with chronological age (A), but strongly associated with WM performance (B). The complex multivariate pattern of brain response could be used to predict WM performance with a relatively high degree of accuracy using a cross-validated multivariate pattern regression (C), which included features from both the executive and default mode system (D). Notably, while both executive and non-executive regions could predict WM performance, maximally accurate predictions required the combined feature set which spanned both networks (E). All data from Satterthwaite et al., 2013.

Studies of resting-state functional connectivity provide evidence regarding the development of interacting functional networks, which support EF. Both cross-sectional [22] and longitudinal studies [23] demonstrate that correlations among regions within the DMN are weak in childhood but become stronger with age. Furthermore, a recent study in a large cohort of youth found that the DMN’s role as a “cohesive connector” system within the functional connectome increased with age, and was correlated with cognitive performance [24]. This finding contrasts with a longitudinal study in young adolescents, which found weaker between network correlations between the central executive network and the DMN with age [23]. The divergence of these findings may be due to the different edge measures used for the network analyses of the two studies: wavelet coherence was used as an edge measure in Gu et al., 2015, which quantifies highly related, but out-of-phase (anti-correlated) signals as strongly connected, and all values range from 0–1. This contrasts with the commonly-used Pearson’s correlation (as in [23]), where out-of-phase signals will be represented with negative values.

Such developmental changes in resting state connectivity have been associated with EF capacity. Hyper-connectivity within the DMN and cingulo-opercular network are seen in children with executive deficits [25]. Greater anti-correlation between the DMN and lateral frontal cortex is associated with better inhibitory performance in children [25], but the relationship between inhibition and strength of anti-correlation between the task-positive executive system and DMN is also stronger in adults than in children [26]. These studies support the idea that the development of functional network topology contributes to the maturation of EF during this critical period.

Moderating factors

Development of EF is influenced by several factors including sex and socioeconomic status (SES). Females demonstrate better working memory and attention from childhood through adolescence [9], though males show more improvement in these domains during adolescence [27]. In contrast, males show better processing speed at the beginning of adolescence but improve less [27]. SES also affects multiple domains of EF, including sustained attention and inhibition [27]. Inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility develop more slowly in preschool-aged children with less access to learning resources [1]. In contrast to findings from behavioral studies, a longitudinal neuroimaging study found an interactive effect of SES and sex on both behavior and brain function, but no effect of SES or sex alone [28]. Sex differences in EF that are present before puberty have been attributed to organizational effects of exposure to gonadal hormones in early development on emerging neural circuits, whereas sex differences that first appear during puberty may be due to activational effects of differences in gonadal steroid levels associated with puberty [29].

Relevance for psychopathology

Executive deficits are present in a wide range psychiatric disorders affecting children and adolescents including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [30], conduct disorder [31], substance use disorders [32], and psychotic disorders [33,34]. Consequences of executive deficits during childhood and adolescence include decreased academic achievement, social isolation, low self-esteem, and risk-taking behavior [35]. Individuals with these disorders are thus most likely to benefit from educational interventions aimed at improving EF. Therefore, understanding how psychopathology is related to failures of executive development is critical.

Recent behavioral studies in neuropsychiatric disorders have examined how executive dysfunction impacts academic and social aspects of school performance, with most evidence accumulating in ADHD and substance use disorders. Developmental trajectories in adolescents with ADHD compared to healthy individuals are delayed for inhibition and shifting but similar for WM and planning [36]. In youths with ADHD, those with worse EF have more problems with academic performance and peer interactions [37]. Additionally, poor EF in adolescence is associated with early and greater use of alcohol and other substances [32].

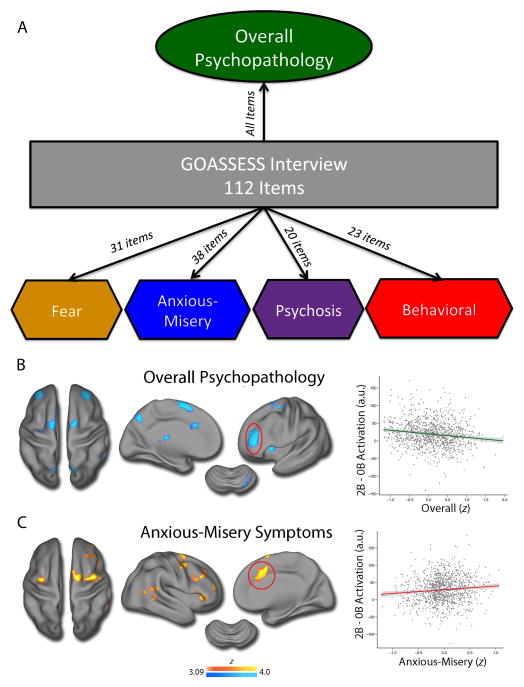

Many neuroimaging studies have examined the relationship between executive system dysfunction and neuropsychiatric disorders during development. Case-control studies often attribute dysfunction of executive regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, and anterior insula to disorders such as ADHD [38], schizophrenia [39], and conduct disorder [40]. However, a recent study of 1,129 youths with diverse psychopathology found that overall psychopathology (as measured using a bi-factor model, Figure 2A) is associated with reduced recruitment of the executive network (Figure 2B) [41]. Such functional data is convergent with recent evidence demonstrating grey matter loss in similar regions across several disorders that exhibit executive deficits [42]. In contrast, anxious-misery symptoms are associated with widespread hyper-activation of the executive network (Figure 2C) [41], suggesting that there are both common and dissociable deficits in executive system recruitment among neuropsychiatric disorders. Taken together, these studies emphasize the degree to which failures of executive function are a central feature of diverse psychopathology that often emerge in school-age children and adolescents, and frequently present as difficulties within educational environments.

Figure 2.

Psychopathology is associated with common and dissociable patterns of executive dysfunction. In a sample of 1,129 youths imaged as part of the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort, a bifactor factor analysis identified common and divergent dimensions of psychopathology across categorical screening diagnoses (A). When these dimensions of psychopathology were related to activation during a fractal version of the n-back working memory task, overall psychopathology across categorical screening diagnoses was associated with hypoactivation of the executive system (B), whereas anxious-misery symptoms (depression, anxiety) were associated with elevated activation of the executive system (C). All data from Shanmugan et al., 2016.

Educational interventions

Understanding executive development and the factors that moderate it are important for developing interventions to improve it. Cognitive remediation has been shown to significantly improve multiple executive domains in patients with schizophrenia [43] and ADHD [44]. These improvements in EF are correlated with changes in brain activation such that cognitive remediation diminishes the degree of hypoactivation observed in psychosis [45]. However, the majority of recent studies proposing educational interventions that would improve EF, such as music and physical education classes, do not include a neuroimaging component, and thus brain-based data are limited. Two recent exceptions include one study that demonstrated improved EF and increased task-induced prefrontal activation in healthy young adults following exercise [46]. Another recent study suggested that musically trained children exhibit better verbal fluency and processing speed as well as increased activation of executive regions [47]. While cognitive training [48], neurofeedback training [49], and mindfulness training [50] are additional methods that have shown early positive results in improving executive deficits, the impact of these interventions on brain function has not yet been evaluated. Given the paucity of studies in this area, it is clear that more work is needed to understand how proposed educational interventions may impact EF at a neural level.

Limitations of current research

While much progress has been made regarding our understanding of executive system development, there are several limitations that should be noted. First, many of the studies investigating EF in development are cross-sectional, and thus are unable to delineate the longitudinal developmental trajectory of EF. While cross-sectional studies are often the basis of longitudinal inferences regarding development, factors such as the selection of time points, trajectory of developmental process, and test-retest reliability of methods employed affect the extent to which cross-sectional findings accurately represent longitudinal processes [51]. Many of the few longitudinal neuroimaging studies suffer from relatively small sample sizes or relatively brief longitudinal follow-up. Furthermore, existing work has used a variety of tasks to probe EF, and results may not be generalizable across tasks or executive domains. Additionally, task difficulty likely decreases with age, and the strategies used to perform such tasks evolve during development [7], limiting the ability to similarly probe EF across age groups.

Similarly, few studies evaluate the impact of educational interventions on brain measures of EF. As such, it is not known how such interventions lead to improvements in EF or whether they produce lasting neural changes that affect the course of executive system development. Additionally, methods of assessing EF and task paradigms vary across studies, limiting replication of existing results.

Future directions

Studies reviewed here emphasize that EF undergoes an extended maturational period throughout childhood and young adulthood. It is clear from both behavioral and neuroimaging studies that different domains of EF exhibit different developmental trajectories. However, charting these trajectories remains incomplete. Large longitudinal neuroimaging studies that consistently account for factors that would affect the course of development are necessary in determining how the executive system develops normally and abnormally in association with performance deficits. Determining the normal developmental trajectory of the executive system is a necessary step in identifying both abnormal development in youth at risk for poor outcomes as well as critical periods where interventions might be most effective. Notably, the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) initiative will provide detailed cognitive and clinical phenotyping in concert with longitudinal multi-modal neuroimaging on a large cohort of 10,000 youth followed over 10 years. This landmark study has the potential to provide data that may transform our understanding regarding how the executive system develops during youth.

Additionally, it is evident that there are several factors that moderate the development of EFs. Preliminary studies indicate cognitive remediation [43,44], cognitive training [48], music classes [47], and physical education [46] may be ways to improve EF during development. However, more information regarding their impact and mode of action are needed before these factors can be used to inform the implementation of educational strategies that can facilitate EF development. For example, while several studies have identified factors that correlate with better or worse EF, the optimal time periods for implementation remain unclear. Similarly, the mechanisms by which educational interventions exert their effects are yet to be determined. Incorporating brain-based measurements within such studies may be an important step in understanding the mechanisms of interventions that have the potential to produce long-term benefits for academic achievement.

Highlights.

The executive system displays a protracted course of development.

Executive system structure, function and connectivity mature into young adulthood.

Neuropsychiatric disorders display common and dissociable executive deficits.

Executive functioning is strongly linked to educational performance.

Few studies directly relate educational interventions to neural markers of EF.

Acknowledgments

TDS was supported by NIMH R01MH107703, R21MH106799, and K23MH098130.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Clark CA, Sheffield TD, Chevalier N, Nelson JM, Wiebe SA, Espy KA. Charting early trajectories of executive control with the shape school. Dev Psychol. 2013;49:1481–1493. doi: 10.1037/a0030578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefevre JA, Berrigan L, Vendetti C, Kamawar D, Bisanz J, Skwarchuk SL, Smith-Chant BL. The role of executive attention in the acquisition of mathematical skills for children in Grades 2 through 4. J Exp Child Psychol. 2013;114:243–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Fuhs MW, Nesbitt KT, Farran DC, Dong N. Longitudinal associations between executive functioning and academic skills across content areas. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1698–1709. doi: 10.1037/a0036633. This large study examined how development of EF is related to academic achievement in school-age children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viterbori P, Usai MC, Traverso L, De Franchis V. How preschool executive functioning predicts several aspects of math achievement in Grades 1 and 3: A longitudinal study. J Exp Child Psychol. 2015;140:38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjowall D, Bohlin G, Rydell AM, Thorell LB. Neuropsychological deficits in preschool as predictors of ADHD symptoms and academic achievement in late adolescence. Child Neuropsychol. 2015:1–18. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2015.1063595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dajani DR, Uddin LQ. Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macdonald JA, Beauchamp MH, Crigan JA, Anderson PJ. Age-related differences in inhibitory control in the early school years. Child Neuropsychol. 2014;20:509–526. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2013.822060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gur RC, Richard J, Calkins ME, Chiavacci R, Hansen JA, Bilker WB, Loughead J, Connolly JJ, Qiu H, Mentch FD, et al. Age group and sex differences in performance on a computerized neurocognitive battery in children age 8–21. Neuropsychology. 2012;26:251–265. doi: 10.1037/a0026712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Evans A, Rapoport J, Giedd J. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006;440:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kharitonova M, Martin RE, Gabrieli JD, Sheridan MA. Cortical gray-matter thinning is associated with age-related improvements on executive function tasks. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2013;6:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *13.Shaw P, Malek M, Watson B, Greenstein D, de Rossi P, Sharp W. Trajectories of cerebral cortical development in childhood and adolescence and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.007. This longitudinal study showed that the trajectory of cortical thinning during development relates to ADHD symptom outcome in adults. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **14.Perlman SB, Huppert TJ, Luna B. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Evidence for Development of Prefrontal Engagement in Working Memory in Early Through Middle Childhood. Cereb Cortex. 2015 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv139. This innovative study used NIRS to demonstrate that prefrontal recruitment in young children (ages 3–7) improved with age during a WM task. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth JR, Burman DD, Meyer JR, Lei Z, Trommer BL, Davenport ND, Li W, Parrish TB, Gitelman DR, Mesulam MM. Neural development of selective attention and response inhibition. Neuroimage. 2003;20:737–751. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00404-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velanova K, Wheeler ME, Luna B. The maturation of task set-related activation supports late developmental improvements in inhibitory control. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12558–12567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1579-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgund ED, Lugar HM, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. The development of sustained and transient neural activity. Neuroimage. 2006;29:812–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brahmbhatt SB, White DA, Barch DM. Developmental differences in sustained and transient activity underlying working memory. Brain Res. 2010;1354:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durston S, Davidson MC, Tottenham N, Galvan A, Spicer J, Fossella JA, Casey BJ. A shift from diffuse to focal cortical activity with development. Dev Sci. 2006;9:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Liston C, Durston S. Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **21.Satterthwaite TD, Wolf DH, Erus G, Ruparel K, Elliott MA, Gennatas ED, Hopson R, Jackson C, Prabhakaran K, Bilker WB, et al. Functional maturation of the executive system during adolescence. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16249–16261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2345-13.2013. This large study of 951 youths demonstrated that increased executive system activation and reciprocal DMN deactivation underlie improvements in WM seen during adolescence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NU, Church JA, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. The maturing architecture of the brain’s default network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman LE, Rudie JD, Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, McNealy K, Dapretto M. Development of the default mode and central executive networks across early adolescence: a longitudinal study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;10:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Gu S, Satterthwaite TD, Medaglia JD, Yang M, Gur RE, Gur RC, Bassett DS. Emergence of system roles in normative neurodevelopment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502829112. This study examined network development in a large cohort of youth and found evidence for system-specific evolution of network modules that relate to cognitive performance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barber AD, Jacobson LA, Wexler JL, Nebel MB, Caffo BS, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH. Connectivity supporting attention in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;7:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **26.Barber AD, Caffo BS, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH. Developmental changes in within- and between-network connectivity between late childhood and adulthood. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.11.011. This resting-state functional connectivity study demonstrated that the correlation between the task-positive executive system and DMN becomes more negative with age, and that the relationship between the strength of anti-correlation between these networks and an individual’s inhibitory control capacity is stronger in adults than in children. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boelema SR, Harakeh Z, Ormel J, Hartman CA, Vollebergh WA, van Zandvoort MJ. Executive functioning shows differential maturation from early to late adolescence: longitudinal findings from a TRAILS study. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:177–187. doi: 10.1037/neu0000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Spielberg JM, Galarce EM, Ladouceur CD, McMakin DL, Olino TM, Forbes EE, Silk JS, Ryan ND, Dahl RE. Adolescent development of inhibition as a function of SES and gender: Converging evidence from behavior and fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:3194–3203. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22838. This longitudinal study examined moderators of the development of executive function, finding evidence of SES impacting the development of inhibitory control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy MM, Arnold AP, Ball GF, Blaustein JD, De Vries GJ. Sex differences in the brain: the not so inconvenient truth. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2241–2247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5372-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol Bull. 1997;121:65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sergeant JA, Geurts H, Oosterlaan J. How specific is a deficit of executive functioning for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:3–28. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Nguyen-Louie TT, Tapert SF. Inhibition during early adolescence predicts alcohol and marijuana use by late adolescence. Neuropsychology. 2014;28:782–790. doi: 10.1037/neu0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forbes NF, Carrick LA, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Working memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2009;39:889–905. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fusar-Poli P, Deste G, Smieskova R, Barlati S, Yung AR, Howes O, Stieglitz RD, Vita A, McGuire P, Borgwardt S. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:562–571. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian Y, Shuai L, Chan RC, Qian QJ, Wang Y. The developmental trajectories of executive function of children and adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:1434–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiang HL, Gau SS. Impact of executive functions on school and peer functions in youths with ADHD. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, Proal E, Di Martino A, Milham MP, Castellanos FX. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1038–1055. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minzenberg MJ, Laird AR, Thelen S, Carter CS, Glahn DC. Meta-analysis of 41 functional neuroimaging studies of executive function in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:811–822. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubia K, Smith AB, Halari R, Matsukura F, Mohammad M, Taylor E, Brammer MJ. Disorder-specific dissociation of orbitofrontal dysfunction in boys with pure conduct disorder during reward and ventrolateral prefrontal dysfunction in boys with pure ADHD during sustained attention. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:83–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **41.Shanmugan S, Wolf DH, Calkins ME, Moore TM, Ruparel K, Hopson RD, Vandekar SN, Roalf DR, Elliott MA, Jackson C, et al. Common and Dissociable Mechanisms of Executive System Dysfunction Across Psychiatric Disorders in Youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060725. appiajp201515060725. This large study used a bi-factor model to represent dimensions of psychopathology, demonstrating that regions of dysfunction previously attributed to individual neuropsychiatric disorders are primarily linked to overall psychopathology across categorical diagnoses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **42.Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, Ortega BN, Zaiko YV, Roach EL, Korgaonkar MS, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:305–315. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2206. This voxel-based morphometry meta-analysis of 193 studies showed that there are common regions of grey matter loss across multiple psychiatric disorders and that grey matter loss in these regions is associated with worse executive functioning. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:472–485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevenson CS, Whitmont S, Bornholt L, Livesey D, Stevenson RJ. A cognitive remediation programme for adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36:610–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, Bray P, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J. Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:144–152. doi: 10.1017/s0007125000161872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **46.Byun K, Hyodo K, Suwabe K, Ochi G, Sakairi Y, Kato M, Dan I, Soya H. Positive effect of acute mild exercise on executive function via arousal-related prefrontal activations: an fNIRS study. Neuroimage. 2014;98:336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.067. This paper is one of the few recent studies showing an effect of a possible educational intervention on both performance and brain measures of executive function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuk J, Benjamin C, Kenyon A, Gaab N. Behavioral and neural correlates of executive functioning in musicians and non-musicians. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cortese S, Ferrin M, Brandeis D, Buitelaar J, Daley D, Dittmann RW, Holtmann M, Santosh P, Stevenson J, Stringaris A, et al. Cognitive training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiner NJ, Frenette EC, Rene KM, Brennan RT, Perrin EC. In-school neurofeedback training for ADHD: sustained improvements from a randomized control trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133:483–492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riggs NR, Black DS, Ritt-Olson A. Applying neurodevelopmental theory to school-based drug misuse prevention during adolescence. New Dir Youth Dev. 2014;2014:33–43. 10. doi: 10.1002/yd.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraemer HC, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Kupfer D. How can we learn about developmental processes from cross-sectional studies, or can we? Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:163–171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]