SUMMARY

BACKGROUND

Despite renewed focus on molecular tuberculosis (TB) diagnostics and new antimycobacterial agents, treatment outcomes for patients co-infected with drug-resistant TB and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remain dismal, in part due to lack of focus on medication adherence as part of a patient-centered continuum of care.

OBJECTIVE

To review current barriers to drug-resistant TB-HIV treatment and propose an alternative model to conventional approaches to treatment support.

DISCUSSION

Current national TB control programs rely heavily on directly observed therapy (DOT) as the centerpiece of treatment delivery and adherence support. Medication adherence and care for drug-resistant TB-HIV could be improved by fully implementing team-based patient-centered care, empowering patients through counseling and support, maintaining a rights-based approach while acknowledging the responsibility of health care systems in providing comprehensive care, and prioritizing critical research gaps.

CONCLUSION

It is time to re-invent our understanding of adherence in drug-resistant TB and HIV by focusing attention on the complex clinical, behavioral, social, and structural needs of affected patients and communities.

Keywords: drug-resistant TB, HIV, medication adherence, patient-centered care

APPROXIMATELY 1.5 MILLION people are living with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) worldwide. While the overall TB epidemic is very slowly being brought under control, the number of TB patients with drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) continues to rise. In 2013 alone, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 480 000 individuals developed MDR-TB, an increase of 80% from 2000 estimates.1 Globally, MDR-TB is associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,2 and HIV exacerbates TB clinically and in terms of social impact.3 In South Africa, the epicenter of the drug-resistant TB-HIV syndemic, up to 80% of patients with extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) are HIV co-infected. Even in low HIV burden countries, the proportion of DR-TB patients with HIV co-infection ranges between 7% and 23%.4,5

Treatment of DR-TB in low- and middle-income settings is fraught with clinical, operational and social challenges. Patients with DR-TB/HIV take an average of six antimycobacterial medications for >18 months in addition to lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART). Treatment is often centralized, and involves social marginalization, family isolation, difficult and painful treatment regimens, dual stigmatization, and economic loss.3,6,7 In contrast, drug-susceptible TB is typically treated over a period of 6 months, with far fewer and far less toxic medications, through largely decentralized channels of care. While recent innovations in TB diagnostics, such as the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), have enhanced MDR-TB case detection, cure rates remain appallingly low.1 Poor treatment outcomes have a number of potential causes. Low levels of medication adherence are predicted to be an important cause of treatment failure,8,9 and are strongly associated with failure to convert TB culture to negative during treatment.8–10

Medication adherence in ART has been carefully studied.11 Each medication has a defined adherence-resistance relationship, which is a function of the potency of the medication and replicative capacity of drug-resistant organisms. Time on ART as well as patterns of treatment interruptions also influence drug resistance-induced treatment failure.11–13 In contrast to HIV, medication adherence in DR-TB-HIV is substantially understudied.14–18 Preliminary research from South Africa finds that XDR-TB/HIV co-infected patients report significantly lower adherence to TB medications than ART.10 High ART adherence with low TB medication adherence may improve patient survival without improving TB treatment outcomes,19 and contribute to ongoing transmission.

Although the WHO has endorsed more progressive approaches, such as the International Standards for Tuberculosis Care,20,21 the reality is that anti-tuberculosis treatment programs around the world focus on directly observed therapy (DOT) as the centerpiece of treatment delivery and adherence support. As an isolated intervention, DOT lacks a rigorous evidence base and is often at odds with patient needs and preferences.3,22–24 From the health systems perspective, DOT programs may integrate poorly into health systems, face technical challenges and variability of access, and poorly address stigma.24–26 To improve adherence in DR-TB/HIV, there is an urgent need to evaluate patient-centered care approaches that look beyond DOT, in particular its conventional facility-based form. Although HIV care delivery can inform future advances in TB management, long-term HIV management itself requires paradigm shifts from centralized to decentralized, patient-focused approaches that address the waiting times for ART refills, improved management of medical complications, transportation barriers, and burden on the strained health care workforce.25

A patient-centered approach to adherence in DR-TB and HIV treatment that reflects the Institute of Medicine (Washington DC, USA) recommendation for ‘partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families (when appropriate) to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care’ is imperative.26,27 In other words, not only should we recognize the time, cost and quality of health care services, we should also consider the patient’s perspective and build on patient-provider relationships to enhance the humaneness of care through communication, shared decision-making and support for self-management. Patient-centered care has been shown to have positive effects on patient behavior, well-being, and treatment outcomes.28 For treatment of DR-TB and HIV, successful programs have included important elements of patient-centered care, including emphasizing patient preference; decentralized, community-based care;29 and intensive counseling, accompaniment,30 and support; while programs using mostly conventional models of care have shown poor outcomes.31

We conceptualize patient-centered care as being oriented toward addressing patients’ priorities, not in the sense of a menu of choices, but rather as a holistic model of health care delivery that considers the patient as the central figure in the process or continuum of care. A patient-centered approach is therefore not a one-size-fits-all solution to the multifactorial patient-related barriers to MDR/XDR-TB/HIV treatment adherence that have been identified, including high TB pill burden and adverse drug effects, lack of patient education and counseling, provider supervision of anti-tuberculosis treatment, inability to access care in the community, and the stigma of public TB notification.3,7,10 Conversely, a patient-centered approach is a flexible model of care that reacts to the specialized needs of individuals. Studies of DR-TB/HIV co-infected patients have identified HIV-specific services as facilitators of ART adherence, including treatment literacy counseling, patient involvement in care, and simpler drug regimens.3,32

Patient-centered care depends on engaging each individual patient with tailored education/counseling, understanding their motivations, and enhancing behavioral skills within the context of local social, structural and cultural factors. A patient-centered approach is particularly critical in vulnerable and marginalized MDR-/XDR-TB patients. The current model of care in much of the world, which relies on a clinician to examine the MDR-TB/HIV patient and prescribe TB medications without input from counselors, social workers or mental health professionals, much less patients, addresses very little of this vulnerability. A team-based approach that includes mental health trained providers, social work trained providers, and behavioral counselors who can engage with patients more directly and holistically, and explicitly integrates HIV and DR-TB care, allows us to think about and make treatment decisions that encompass the full range of clinical, socio-economic and structural issues confronting patients.

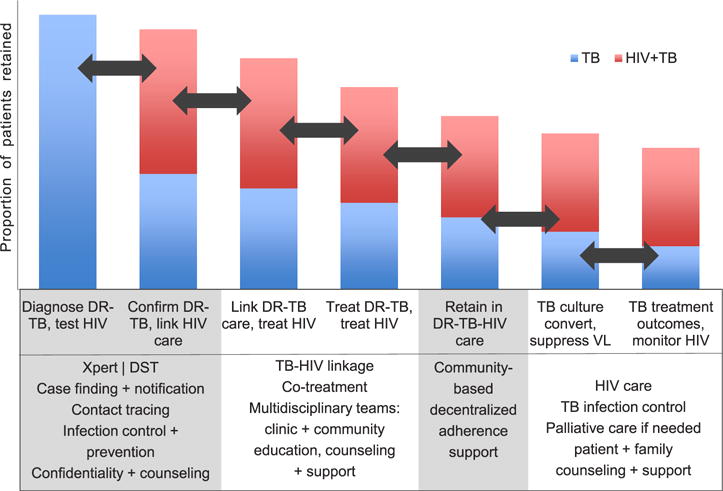

Patient-centered approaches recognize that comprehensive care must be provided along a locally contextualized continuum of services. The continuum or cascade of care for DR-TB/HIV describes the complex, integrated steps from diagnosis to cure. In DR-TB/HIV, this should incorporate early TB diagnosis and drug susceptibility testing, early HIV diagnosis, comprehensive patient education and support, infection control, streamlined entry into co-treatment, unimpeded access to medications, adherence support, and retention in dual care. For patients cured of DR-TB, the cascade should conclude with support for reintegration back into the community, family life, and employment. For patients with disease considered incurable, it must include palliative care (Figure). The decline between steps in the continuum represents patient attrition, and underscores the need to improve care and retention at each step.

Figure.

The continuum of DR-TB/HIV care defines the processes and linkages that comprise optimal care for MDR-/XDR-TB/HIV. The y-axis represents patients retained in care; the x-axis represents the stages of the continuum; the arrows represent the linkages in the continuum. The box below defines tasks and processes that occur at each stage. TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; DR-TB = drug-resistant TB; VL = viral load; DST = drug susceptibility testing; MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant TB; XDR-TB = extensively drug-resistant TB. This image can be viewed online in colour at http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iuatld/ijtld/2016/00000020/00000004/art00004

In March 2015, a meeting of clinicians, behavioral and social scientists, patients, and activists convened at the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, to generate a call to action for patient-centered care in the treatment of DR-TB/HIV. We commit to working with affected communities to improve medication adherence by re-inventing models of care delivery that respect and address patients’ needs. This commitment is based on the following principles that emerged from the 2015 symposium:

Patient-centered care is team-based, decentralized care that requires substantial investment in human resources to provide high-quality care in settings where patients live and work, and are connected to networks of social capital and social support.

Patient education and counseling—with the goals of patient empowerment, treatment literacy, accountability, and reducing stigma—should be at the heart of adherence support for DR-TB/HIV. Core standards in counseling and education for DR-TB/HIV need to be developed, as education and DOT may have different meanings and are implemented differently throughout the world.

Public health approaches to DR-TB/HIV should be based on human rights and equity. Where public health and individual rights conflict—for example, the forcible detention or isolation of people with infectious XDR-TB to protect others from transmission—a rights-based approach will use deliberation in accordance with the Siracusa Principles33 to justify rights-limiting public health measures.

Patient-centered care does not mean centering all responsibility on the person with TB. Grounding patient-centered care in rights-based approaches recognizes that governments and health systems must bear the responsibility to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health along the cascade of care.

There are critical research gaps in understanding the cascade of care for DR-TB/HIV, including biomedical, behavioral, and implementation science components. This research agenda must be urgently prioritized in parallel with operationalizing patient-centered practices, and donors should commit to funding this research.

The development of new TB diagnostics, drugs, and treatment regimens presents exciting opportunities to improve outcomes and reduce community transmission of DR-TB. With innovative and effective approaches to patient-centered care, the opportunity to impact the epidemic afforded by new diagnostics and drugs may not be realized. It is time for clinicians, researchers and TB practitioners to re-invent the understanding of adherence in DR-TB/HIV to eliminate disease and stigma by focusing efforts and attention on affected patients and communities.

Acknowledgments

On behalf of the attendees of ‘Re-inventing adherence: patient-centered care for drug-resistant TB and HIV’, 19–20 March 2015, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. The symposium was supported by the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health (New York, NY), Centre for AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (Durban, South Africa), ICAP (New York, NY), Treatment Action Group (New York, NY), and the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund (New York, NY, USA).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. (WHO/HTM/TB/2014.08). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesfin YM, Hailemariam D, Biadgilign S, Kibret KT. Association between HIV/AIDS and multi-drug resistance tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e82235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daftary A, Padayatchi N, O’Donnell M. Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: a qualitative study of drug-resistant TB-HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. Global Public Health. 2014;9:1107–1116. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.934266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Towards universal access to diagnosis and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis by 2015: WHO progress report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. (WHO/HTM/TB/2011.3). http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2011/mdr_report_2011/en/. Accessed December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaakidis P, Das M, Kumar AM, et al. Alarming levels of drug-resistant tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in metropolitan Mumbai, India. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e110461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pooran A, Pieterson E, Davids M, Theron G, Dheda K. What is the cost of diagnosis and management of drug resistant tuberculosis in South Africa? PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e54587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brust JC, Shah NS, van der Merwe TL, et al. Adverse events in an integrated home-based treatment program for MDR-TB and HIV in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:436–440. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828175ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipsitch M, Levin BR. Population dynamics of tuberculosis treatment: mathematical models of the roles of non-compliance and bacterial heterogeneity in the evolution of drug resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:187–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senthilingam M, Pietersen E, McNerney R, et al. Lifestyle, attitudes and needs of uncured XDR-TB patients living in the communities of South Africa: a qualitative study. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20:1155–1161. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donnell MR, Wolf A, Werner L, Horsburgh CR, Padayatchi N. Adherence in the treatment of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:22–29. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genberg BL, Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Patterns of antiretroviral therapy adherence and impact on HIV RNA among patients in North America. AIDS. 2012;26:1415–1423. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354bed6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyugi JH, Byakika-Tusiime J, Ragland K, et al. Treatment interruptions predict resistance in HIV-positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS. 2007;21:965–971. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802e6bfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenblum M, Deeks SG, van der Laan M, Bangsberg DR. The risk of virologic failure decreases with duration of HIV suppression, at greater than 50% adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLOS ONE. 2009;4:e7196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Boogaard J, Boeree MJ, Kibiki GS, Aarnoutse RE. The complexity of the adherence-response relationship in tuberculosis treatment: why are we still in the dark and how can we get out? Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner EM, Burman WJ, Steiner JF, Anderson PL, Bangsberg DR. Antiretroviral medication adherence and the development of class-specific antiretroviral resistance. AIDS. 2009;23:1035–1046. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ba8ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangsberg DR, Acosta EP, Gupta R, et al. Adherence-resistance relationships for protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors explained by virological fitness. AIDS. 2006;20:223–231. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000199825.34241.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatano H, Lampiris H, Fransen S, et al. Evolution of integrase resistance during failure of integrase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:389–393. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c42ea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maggiolo F, Airoldi M, Kleinloog HD, et al. Effect of adherence to HAARTon virologic outcome and on the selection of resistance-conferring mutations in NNRTI- or PI-treated patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8:282–292. doi: 10.1310/hct0805-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakaya J, Raviglione M. Quality tuberculosis care. All should adopt the new international standards for tuberculosis care. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:397–398. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201401-014ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopewell PC, Fair EL, Uplekar M. Updating the International Standards for Tuberculosis Care. Entering the era of molecular diagnostics. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:277–285. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201401-004AR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volmink J, Garner P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003343. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003343.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLOS MED. 2007;4:e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasipanodya JG, Gumbo T. A meta-analysis of self-administered vs directly observed therapy effect on microbiologic failure, relapse, and acquired drug resistance in tuberculosis patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:21–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelnick J, O’Donnell M. Expansion of the health workforce and the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1639–1640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc080048. author reply 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM, editors. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loveday M, Padayatchi N, Voce A, Brust J, Wallengren K. The treatment journey of a patient with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa: is it patient-centred? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(Suppl 1):S56–S59. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD003267. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brust JC, Shah NS, Scott M, et al. Integrated, home-based treatment for MDR-TB and HIV in rural South Africa: an alternate model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:998–1004. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seung KJ, Keshavjee S, Rich ML. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a017863. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dheda K, Shean K, Zumla A, Badri M, et al. Early treatment outcomes and HIV status of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furin J, Isaakidis P, Reid AJ, Kielmann K. ’I’m fed up’: experiences of prior anti-tuberculosis treatment in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:1479–1484. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The Siracusa principles on the limitation and derogation provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Geneva, Switzerland: UNCHR; 1984. [Google Scholar]