Abstract

The alveolar epithelium of the lung constitutes a unique interface with the outside environment. This thin barrier must maintain a surface for gas transfer while being continuously exposed to potentially hazardous environmental stimuli. Small differences in alveolar epithelial barrier properties could therefore have a large impact on disease susceptibility or outcome. Moreover, recent work has focused attention on the alveolar epithelium as central to several lung diseases, including acute lung injury and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Although relatively little is known about the function and regulation of claudin tight junction proteins in the lung, new evidence suggests that environmental stimuli can influence claudin expression and alveolar barrier function in human disease. This review considers recent advances in the understanding of the role of claudins in the breakdown of the alveolar epithelial barrier in disease and in epithelial repair.

Barrier function in the lung

As the field of barrierology has emerged over the past 10 years, increasing attention has been directed toward the role of tight junction proteins, including claudins, in determining specific barrier properties of epithelia in health and disease (1). Significant strides have been made in the understanding of renal and intestinal epithelial barrier regulation by claudins; however, relatively little is known about the nature and regulation of tight junctions in the lung. Consideration of the unique requirements of the epithelial barrier in the airway and alveolar epithelium highlights the importance of additional investigation into the make-up and regulation of lung tight junctions. Most remarkable is the considerable surface area of the alveolar epithelium, which equals approximately 75 square meters. This epithelial barrier is less than one micron thick and is exposed daily to more than 8,500 liters of air from the outside environment. The alveolar epithelium is made up of type 1 and type 2 cells, the former comprising 95% of the surface area of the lung. Although the alveolar barrier includes both endothelial and epithelial cells, the critical role of the epithelium is highlighted by data demonstrating that changes in epithelial permeability alone are sufficient to cause pulmonary edema (2). This is because endothelial permeability is relatively high at baseline—for example, the protein concentration of lung lymph fluid is more than 60% of the plasma protein concentration (3).

In addition to the requirement for low macromolecule permeability in the alveolar epithelium, transepithelial ion transport plays a fundamental role in the regulation of airway surface liquid height and composition, as well as in the removal of edema fluid from the airspaces (4). Alveolar fluid clearance in the resolution of edema is the energy-dependent removal of water from the airspaces down a sodium concentration gradient. Sodium-potassium ATPase establishes this gradient, and transepithelial sodium transport is regulated at several levels, including by apical epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) expression and conductance (5). To minimize the energy requirement for this sodium gradient, transepithelial chloride transport is also regulated via channels such as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR); in high-transport conditions, sodium transport can become limited by chloride conductance (6, 7). Importantly, a sizable portion of transepithelial chloride conductance occurs via the paracellular route in the alveolar epithelium (4, 8). The precise mechanisms for water transport in the alveolar epithelium remain obscure. Although transcellular water conductance through aquaporins likely plays a role, data from mice genetically deficient in aquaporins suggest that alternate pathways can at least compensate for the absence of these channels (9); however, the paracellular route may be a key mechanism for transepithelial water transport. Therefore, an idealized conception of alveolar epithelial tight junction properties would include low permeability to macromolecules and ions, but also relatively anion-selective paracellular ion transport, and potentially water transport.

Disruption of epithelial barrier function is fundamental to many lung diseases, of which the most notable is acute lung injury. This includes the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is primarily characterized by increased alveolar barrier permeability and impaired alveolar fluid clearance. In this syndrome of respiratory failure, preserved epithelial barrier function is inversely associated with patient mortality (10). Therefore, changes in paracellular ion or macromolecule permeability in the alveolar epithelium may have a direct role in the pathogenesis of this disease. Recent data suggest that differential expression of claudins may play a role in epithelial barrier changes in acute lung injury.

Claudin expression in the lung

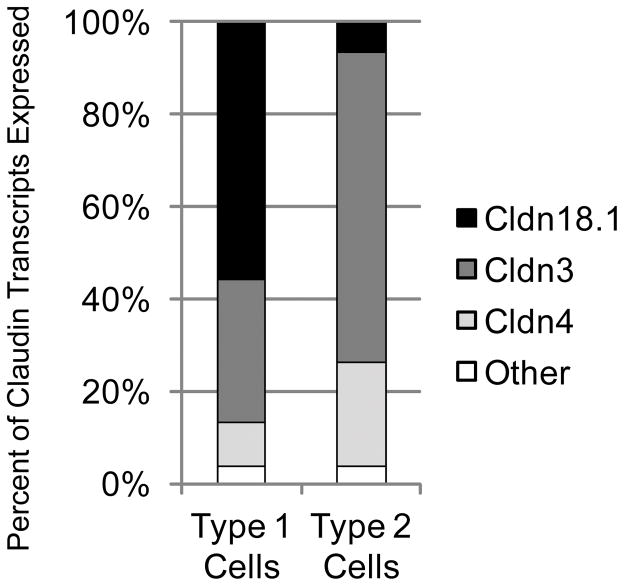

The particular claudin expression profiles of human alveolar epithelial cells are not fully known. To begin to determine which claudins are expressed in the alveolar epithelium and how claudins might influence barrier function in the lung, our group used cell-type specific markers and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) to purify populations of type 1 and type 2 cells from rat lungs (11). Using quantitative real-time PCR, we found that both cell types primarily expressed three claudins: claudin-3, claudin-4, and claudin-18.1. In each cell type, these claudins comprised greater than 97% of claudin transcripts, but the proportion of each of the claudins was different in the two cell types (Figure 1). In type 1 cells—the cell type covering most of the alveolar epithelial surface—claudin-18.1 was the most abundantly expressed transcript, while in type 2 cells claudin-3 was the dominant transcript. Both cells expressed relatively high levels of claudin-4. In the healthy lung, type 1 cells form tight junctions with both type 2 cells and other type 1 cells, while type 2 cells form tight junctions primarily with type 1 cells. Of these three claudins expressed in the alveolar epithelium, only claudin-18.1 is unique to the lung (12), suggesting a lung-specific function. Because claudin-18.1 is the dominant transcript in type 1 cells, it is likely that any unique properties of this protein would partly characterize junctions between type 1 cells. Note that the splice variant claudin-18.2 is expressed in the stomach. Although claudins-1, -5, -7, -12, -15, and -23 are expressed at low levels in alveolar epithelial cells (11), it is possible that they make important contributions to the alveolar epithelial barrier.

Figure 1.

Claudin mRNA expression profiles of primary alveolar epithelial type 1 and type 2 cells. FACS-sorted, freshly-isolated primary rat alveolar epithelial cells predominantly express claudin-3, claudin-4 and claudin-18.1 with transcripts for these claudins accounting for 97% of all claudin transcripts in these cells. In type 1 cells claudin-18.1 is the most abundant transcript, while in type 2 cells claudin-3 is the major transcript. Both cell types express claudin-4. Adapted from reference 11.

The airway epithelium is made up of more diverse cell types, including Clara cells, ciliated and non-ciliated epithelial cells, goblet cells, neuroendocrine cells, dendritic cells and others. The specific claudins expressed in each of these cells is not yet known, but transcripts for at least claudins-1, -3, -4, -5, -7, -10, -12, -15 and -18.1 are expressed in whole airway lysates. Studies have identified claudin-1 and -7 expression in airway dendritic cells within the airway epithelium (13), and claudin-1 in airway smooth muscle cells (14); claudin-5 is predominantly expressed in endothelial cells (15). In whole human lung tissue, the most abundant claudin transcripts are claudin-1, -3, -4, -5, -7, -8, -10, -12, -18.1 and -23. This is similar to expression profiles in rat and mouse, but levels of claudin-15 are probably higher in rodents than in humans based on unpublished data from our laboratory.

Regulation and function of claudins in the alveolar epithelium in acute lung injury

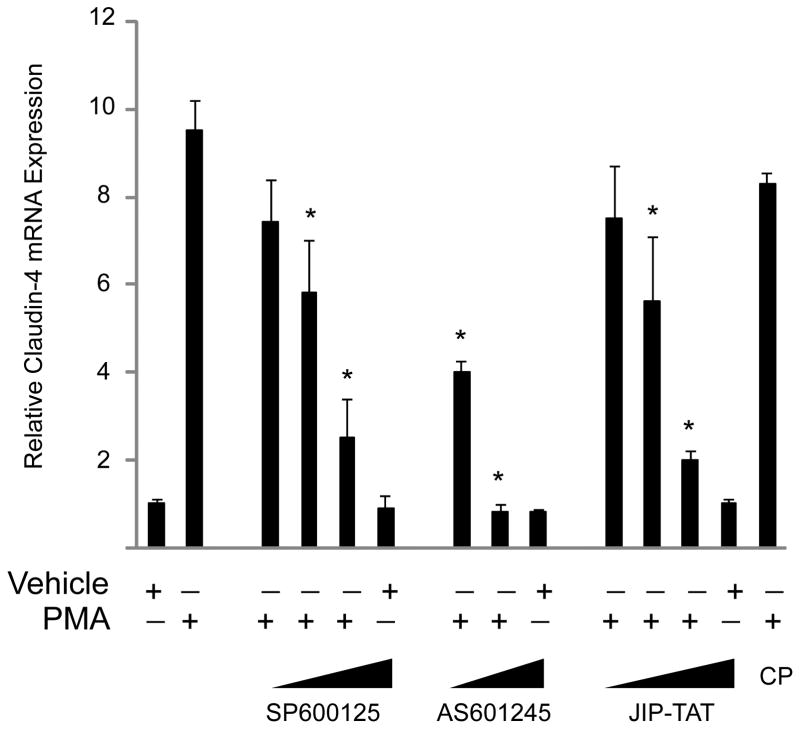

Although claudin expression is not the only mechanism by which cells regulate paracellular permeability, changes in claudin expression in pathological states may provide insight into the contributions of individual proteins to epithelial barrier function. Of the three dominant claudins in the alveolar epithelium, two show notable changes in expression during acute lung injury—claudin-4 and claudin-18 (16–18). Interestingly, regulation of these two proteins is in opposite directions: claudin-4 expression is increased in acute lung injury, while claudin-18 expression may be decreased. The changes in claudin-4 levels appear to be rapid, with an 8-fold increase in mRNA levels by 4h in the ventilator-induced lung injury mouse model. The mechanisms for the increase in claudin-4 expression are not fully known, but data from our group show that protein kinase C (PKC) activation was sufficient to increase claudin-4 mRNA levels, and that downstream jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibition blocked this effect in cultured primary rat and human lung epithelial cells (16) (Figure 2). Inhibition of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK did not change PKC-mediated claudin-4 induction in these primary lung cells. It is notable that the claudin-4 promoter contains a conserved, putative AP-1 consensus sequence at the transcription start site, which raises the possibility that JNK may act through AP-1 to increase claudin-4 expression. Previous studies have also shown that SP-1 and the grainyhead transcription factor Ghl2 may be important for basal expression of claudin-4 (19–21). In cultured lung epithelial cells, MDCK cells, and in chick intestinal epithelial cells, epidermal growth factor (EGF) increases claudin-4 levels (20, 22, 23). In the A431 carcinoma cell line, claudin-4 has been reported to be part of a potential protein signature of EGF receptor inhibition; that is, EGFR activation increases claudin-4 expression (24). Interestingly, the barrier-enhancing properties of EGFR on airway epithelial cells appear to be dependent on JNK activation (25). In addition, interferon has also been shown to specifically increase claudin-4 expression by a STAT2-dependent mechanism (26). Others have shown that the flavonoid quercetin specifically induced claudin-4 expression in Caco2 cells: the kinase inhibitors H7 and staurosporine blocked this effect (27). These inhibitors target PKC and several other kinases. These data constitute groundwork for the mechanistic regulation of claudin-4 expression, but it is not known if any of the pathways identified in these cell culture studies influence the induction of claudin-4 with epithelial cell injury in vivo.

Figure 2.

Protein kinase C activation induces claudin-4 expression via a JNK-dependent pathway. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), an activator of several PKC isoforms, induces a significant increase in claudin-4 expression in primary in primary human type 2-like distal lung epithelial cells at 4h. This effect was completely inhibited by the protein kinase C inhibitor Gö6850 (not shown). Inhibition of the JNK MAPK pathway with each of three inhibitors (SP600125, AS601245, and JIP-TAT peptide) blocked the PMA-induced increase in claudin 4 expression in a dose-dependent fashion (*P < 0.05 compared with PMA control, data are mean ± SEM, CP = control TAT peptide). Adapted from reference 16.

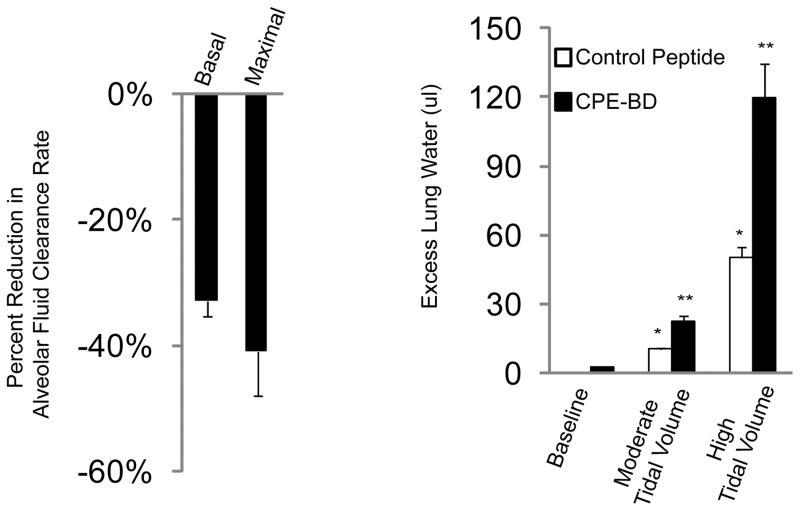

Previous work in MDCK cells has shown that one property of claudin-4 is the formation of a relatively anion-selective paracellular pore pathway (28). Although knock down of claudin-4 in this cell type decreases transepithelial electrical resistance, it also results in decreased paracellular anion selectivity as measured by dilution potential. Separate studies have shown that phosphorylation of claudin-4 by WNK-4 in renal epithelial cells enhances membrane localization of claudin-4 and increases transepithelial chloride conductance (29). This is intriguing because WNK-4 is an activator of chloride conductance in the nephron. Together, these data suggest that claudin-4 limits transepithelial ion transport, and confers a greater barrier to sodium than to chloride. In primary cultured rat alveolar type 2 cells, claudin-4 knock down with siRNA decreased transepithelial electrical resistance without changing paracellular macromolecule permeability (16). Considering the role of chloride transport in the resolution of pulmonary edema in lung injury, the hypothesis emerges that increased claudin-4 expression may be part of an adaptive mechanism to enhance the alveolar epithelial barrier and accelerate the resolution of lung edema. In a mouse model of acute lung injury, claudin-4 expression was rapidly and significantly increased. In in vivo studies, peptide inhibition of claudin-4 and -3 with the binding domain of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin binding domain (CPEBD) resulted in a significant reduction in alveolar fluid clearance rates without affecting permeability to macromolecules in uninjured mice. CPEBD decreased protein levels of claudin-4, and to a lesser extent, claudin-3 in the absence of cytotoxicity. Mice treated with CPEBD also developed more severe lung injury and pulmonary edema when exposed to lung injury (16) (Figure 3). These data further support a protective role for claudin-4 in epithelial barrier function, and suggest that one mechanism by which claudin-4 limits edema is by establishing a paracellular sodium barrier to accelerate alveolar fluid clearance.

Figure 3.

Claudin-3 and -4 knock down impairs alveolar fluid clearance and increases lung injury severity in vivo. Clostridium perfringens binding domain peptide (CPE-BD) significantly reduced rates of alveolar fluid clearance by 35–40% in healthy mice. Both basal and beta-adrenergic-stimulated (maximal) rates of alveolar fluid clearance were significantly lower as compared with mice receiving a control peptide (left). Mice given CPE-BD and then exposed to moderate or severe lung injury via escalating tidal volumes on a mechanical ventilator developed more severe pulmonary edema (excess lung water) compared with mice given a control peptide (*P < 0.05 compared with baseline lung water, **P< 0.05 compared with control peptide-treated mice). Despite reduced rates of fluid clearance at baseline, claudin-3 and -4 knock down did not induce pulmonary edema in the absence of an additional injurious stimulus. Adapted from reference 16.

Claudin-4 and alveolar barrier function in human lungs

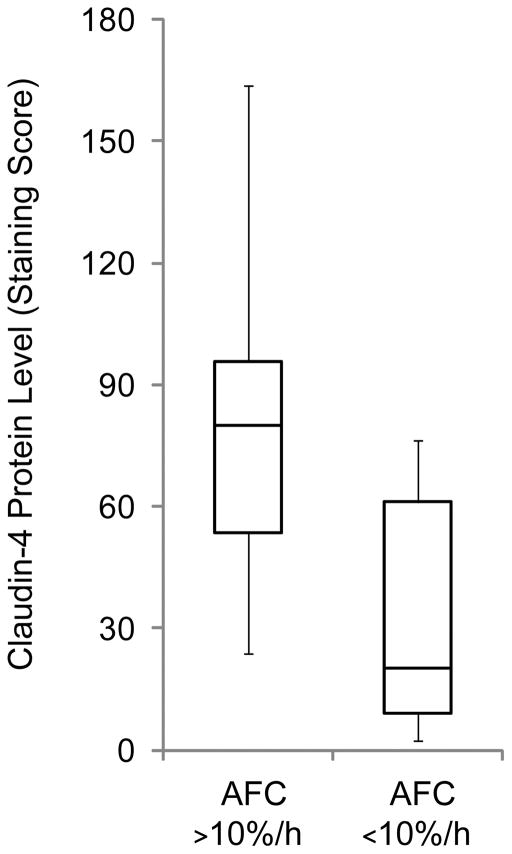

Because experimental studies implicate a potential protective role of claudin-4 in the alveolar epithelium, we tested the hypothesis that differences in claudin-4 levels are associated with alveolar barrier function in human lungs rejected for transplantation (30). Lungs are rejected for transplantation for a variety of reasons, including the presence of clinical lung injury in the donor. Therefore, some lungs rejected for transplant are significantly injured and others are not, but all of the lungs undergo ischemia and reperfusion. In this study, we measured claudin-4 expression in rejected donor lungs using immunostaining and immunoblotting. Claudin-4 levels were quantified on immunostained sections using an automated digital scoring technique that represents, in a single number, the staining intensity and the percentage of cells staining positive. By examining multiple sections from donor lungs, a metric for comparing claudin-4 expression was established. Using an ex vivo perfused lung model (31), alveolar epithelial barrier function was assessed in the donor lungs. Specifically, the rate of alveolar fluid clearance was measured and then compared with claudin-4 staining scores. The data showed a non-normal distribution of claudin-4 levels in the donor lung population. Interestingly, as claudin-4 staining scores increased, alveolar fluid clearance also increased (rs = 0.7, P<0.05 by Spearman rank correlation) (30). Therefore, consistent with the animal and cell culture data, it appears that higher levels of claudin-4 may favor higher rates of alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Claudin-4 levels are associated with alveolar fluid clearance rates in human lungs rejected for transplantation. Claudin-4 protein expression levels as assessed by immunostaining were significantly higher in lungs with more preserved alveolar fluid clearance rates. Alveolar fluid clearance was measured in an ex vivo perfused organ system (P < 0.01 for this comparison by Mann-Whitney U). Adapted from reference 30.

To determine if differences in claudin-4 levels were specific—that is, whether claudin-4 was acting as an epithelial cell marker only—levels of other tight junction proteins were also measured. These included claudins-3 and -15, occludin, and ZO-1. Among these only claudin-4 levels varied with alveolar fluid clearance rates. In addition, cytokeratin staining showed that claudin-4 levels appeared to vary in epithelial cells and that epithelial cell abundance was comparable in all of the samples studied. These data suggest that claudin-4 levels are dynamic in alveolar epithelial cells during acute lung injury.

To examine if there was an association between claudin-4 expression and surrogate clinical measures of alveolar barrier function, donor lungs were divided into two groups using a clinical lung injury score of 1 to divide the data into two roughly equally sized groups. The 4-point clinical lung injury score is derived from measures of oxygenation, mechanical ventilator requirements, and radiographic abnormalities (32); higher scores indicate more severe injury. The data showed that higher levels of claudin-4 were present in lungs with less severe clinical lung injury (30). Because levels of claudin-4 were higher in nearly all of the donor lungs than in normal lungs, these data support the hypothesis that lung injury results in a specific induction of claudin-4, and higher levels of claudin-4 contribute to more preserved alveolar barrier function during injury; however, differences in disease time course, epithelial cell type abundance, and other factors could not be assessed with the available data and remain to be investigated.

A role for claudin-4 in epithelial repair?

Published data to date are consistent with the conclusion that claudin-4-mediated effects on paracellular ion selectivity contribute to the differences in alveolar barrier properties in experimental studies and in human lungs. However, claudin-4 expression patterns in diverse epithelia and in cancer cells raise the possibility that claudin-4 could have an additional unique function in epithelial repair. Notably, claudin-4 is expressed in most epithelial tissues. Although this remains to be determined, it is possible that the effects of claudin-4 on paracellular ion selectivity are less important to barrier function in some organs, such as ovarian surface epithelium, skin, airway epithelium, and intestine. One recent study examined the effect of claudin-4 over-expression on barrier properties in primary rat alveolar epithelial cells in culture. In that study, increased claudin-4 expression did not affect paracellular charge selectivity, suggesting that higher claudin-4 expression levels may not alter paracellular chloride permeability in this cell type (33). In airway epithelial cells, as opposed to alveolar epithelium, the potential contribution of claudin-4 to ion transport and airway surface liquid height and composition are not certain, but previous studies have shown that airway epithelial cell injury is sufficient to significantly induce claudin-4 expression (34).

In the naphthalene model of Clara cell injury, naphthalene is administered intraperitoneally to mice, resulting in the selective loss of this cell type from the conducting airways. Cytotoxicity is due to the presence of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2F2 in Clara cells that converts naphthalene to a toxic metabolite. In the 24–36 hours after Clara cell loss, adjacent ciliated epithelial cells squamate and spread to cover the denuded airway epithelium. This is followed by progenitor cell proliferation, and ultimately cells differentiate into the various constituents of the normal airway. Interestingly, at 24 hours after naphthalene administration, whole genome array data showed that claudin-4 was among the most highly induced genes in the genome (34). As the epithelium repaired over the following two weeks, claudin-4 levels returned to normal. When normal epithelial repair was inhibited in transgenic mice expressing herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase in Clara cells exposed to ganciclovir, claudin-4 levels were persistently elevated (34).

Others have reported that ischemia-reperfusion injury in the gut results in increased claudin-4 expression in migrating epithelial cells at the tips of villi, and that claudin-4 levels returned to baseline once epithelial migration was complete (35). In wounded urothelial cells, claudin-4 expression, but not claudin-8, increased in cells at the leading edge of a repairing wound (36). In urothelial cells claudin-8 is a marker of terminal differentiation. Another group found that injured salivary epithelial cells also showed increased claudin-4 expression and the level of claudin-4 was positively associated with the degree of injury in clinical and experimental studies (37–39). Still others have found that claudin-4 was expressed in developing mouse embryos and appeared to be required for blastocyst formation (40). In inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD3) cells, hypertonic stress induced a specific increase in claudin-4 (41).

Together, all of these studies support a role for claudin-4 in epithelial repair. One hypothesis is that claudin-4 facilitates new tight junction formation. Alternatively, claudin-4 may create a tight junction structure that is favorable to epithelial cell movement during repair. It is also possible that claudin-4 plays a more direct role in epithelial cell movement or differentiation state, a hypothesis suggested by clinical studies and data from tumor cell lines. Claudin-4 expression is increased in several neoplastic tissues, including breast, ovary, pancreas, and prostate, as well as in tumor cell lines (42–57). In human ovarian surface epithelial (HOSE) cells, high levels of claudin-4 expression were associated with a more invasive phenotype and accelerated cell migration (42). Knock down of claudin-4 attenuated this phenotype. The mechanisms that underlie this effect of claudin-4 in HOSE cells remain obscure, but may involve regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression (MMP) or activity (42, 58). In breast cancer, high claudin-4 expression may be a marker for poor prognosis in certain tumor types (50, 59–61). Data from experimental and human lung studies focused on lung alveolar epithelial barrier function and claudin-4 are entirely consistent with an additional role for claudin-4 in the reestablishment of an intact epithelium after injury, but published studies to date have not addressed this possibility.

Claudins-3 and -18.1

The functions of claudins-3 and -18.1 in the alveolar epithelium are largely unexplored. Claudin-3 is the most abundant claudin sequence in rat type 2 alveolar epithelial cells. Recent work on claudin-3 found that, despite significant sequence homology with claudin-4, claudin-3 confered no ion selectivity to the paracellular pathway (33, 62). In cultured primary rat alveolar epithelial cells, over-expression of claudin-3 via adenoviral transduction decreased transepithelial electrical resistance and increased paracellular permeability to macromolecules (33). In MDCK cells, increased claudin-3 expression conferred no paracellular charge selectivity to ion transport, but decreased macromolecule permeability without affecting water permeability (62). It is possible that claudin-3 has a general sealing function, as previous studies have shown that claudin-3, unlike claudin-4, can bind with several other claudins on opposing cells (63). It is also possible that claudin-3 contributes to paracellular water transport, but this has not been fully elucidated. Claudin-3 expression levels were unchanged in a short-term mouse model of acute lung injury (16).

Claudin-18.1 is the only known lung-specific tight junction protein, but whether this protein has a lung-specific function is unknown. Recent work in a claudin-18.2 knock out mouse showed that claudin-18.2 formed distinct tight junction strands in the gastric epithelium that were important to limiting paracellular proton transport (64). Claudin-18.1 (lung) and -18.2 (stomach) differ in sequence in the first extracellular loop, which likely determines ion selectivity, but they share a common sequence in the second extracellular loop and carboxyl-terminal domain. This raises the hypothesis that claudin-18.1 forms distinct strands in the alveolar epithelium, but details regarding claudin-18.1 function, including ion selectivity, have not been reported. Prior studies of experimental lung injury indicate that claudin-18 levels are decreased in the days following bleomycin treatment in mice (18), but it is uncertain whether this represents type 1 cell loss or a specific down-regulation of the protein. Interestingly, in cultured primary human type 2 cells, inflammatory stimuli result in a loss of claudin-18 expression by 24 hours (17).

Conclusions and outlook

Recent work has begun to define the claudin expression profiles in lung cells, an important step in determining how tight junction protein regulation influences paracellular transport. In rodent alveolar epithelium, claudins-3, -4 and -18 predominate. Studies to date have demonstrated a specific induction of claudin-4 in acute lung injury. Available human data and functional studies in animals point to a barrier-enhancing role for claudin-4 in the alveolar epithelium. Although a beneficial effect of claudin-4 on paracellular ion transport may be part of the mechanism for this barrier promoting function in the lung, circumstantial data from other tissues and disease states raise the possibility that claudin-4 may have additional roles in the reestablishment of the epithelial barrier following injury. Because defects in epithelial barrier function in the lung contribute to a variety of lung diseases, future studies of the function and regulation of claudins may provide new therapeutic insights into lung diseases, including acute lung injury, asthma, and pulmonary fibrosis.

References

- 1.Tsukita S, Yamazaki Y, Katsuno T, Tamura A. Tight junction-based epithelial microenvironment and cell proliferation. Oncogene. 2008;27:6930–6938. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorin AB, Stewart PA. Differential permeability of endothelial and epithelial barriers to albumin flux. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47:1315–1324. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.6.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vreim CR, Snashall PD, Demling RH, Staub NC. Lung lymph and free interstitial fluid protein composition in sheep with edema. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:1650–1653. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.6.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay MA, Folkesson HG, Clerici C. Lung epithelial fluid transport and the resolution of pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:569–600. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthay MA, Robriquet L, Fang X. Alveolar epithelium: role in lung fluid balance and acute lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:206–213. doi: 10.1513/pats.200501-009AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang X, Song Y, Hirsch J, Galietta LJ, Pedemonte N, Zemans RL, Dolganov G, Verkman AS, Matthay MA. Contribution of CFTR to apical-basolateral fluid transport in cultured human alveolar epithelial type II cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L242–249. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00178.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang X, Fukuda N, Barbry P, Sartori C, Verkman AS, Matthay MA. Novel role for CFTR in fluid absorption from the distal airspaces of the lung. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:199–207. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KJ, Cheek JM, Crandall ED. Contribution of active Na+ and Cl− fluxes to net ion transport by alveolar epithelium. Respir Physiol. 1991;85:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(91)90065-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verkman AS, Matthay MA, Song Y. Aquaporin water channels and lung physiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L867–879. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.5.L867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware LB, Matthay MA. Alveolar fluid clearance is impaired in the majority of patients with acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1376–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2004035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaFemina MJ, Rokkam D, Chandrasena A, Pan J, Bajaj A, Johnson M, Frank JA. Keratinocyte growth factor enhances barrier function without altering claudin expression in primary alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L724–734. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00233.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tureci O, Koslowski M, Helftenbein G, Castle J, Rohde C, Dhaene K, Seitz G, Sahin U. Claudin-18 gene structure, regulation, and expression is evolutionary conserved in mammals. Gene. 2011;481:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung SS, Fu SM, Rose CE, Jr, Gaskin F, Ju ST, Beaty SR. A major lung CD103 (alphaE)-beta7 integrin-positive epithelial dendritic cell population expressing Langerin and tight junction proteins. J Immunol. 2006;176:2161–2172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita H, Chalubinski M, Rhyner C, Indermitte P, Meyer N, Ferstl R, Treis A, Gomez E, Akkaya A, O’Mahony L, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Claudin-1 expression in airway smooth muscle exacerbates airway remodeling in asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1612–1621. e1618. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita K, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Endothelial claudin: claudin-5/TMVCF constitutes tight junction strands in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:185–194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wray C, Mao Y, Pan J, Chandrasena A, Piasta F, Frank JA. Claudin-4 augments alveolar epithelial barrier function and is induced in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L219–227. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00043.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang X, Neyrinck AP, Matthay MA, Lee JW. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells restore epithelial protein permeability in cultured human alveolar type II cells by secretion of angiopoietin-1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26211–26222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta H, Chiba S, Ebina M, Furuse M, Nukiwa T. Altered expression of tight junction molecules in alveolar septa in lung injury and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L193–205. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00349.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werth M, Walentin K, Aue A, Schonheit J, Wuebken A, Pode-Shakked N, Vilianovitch L, Erdmann B, Dekel B, Bader M, Barasch J, Rosenbauer F, Luft FC, Schmidt-Ott KM. The transcription factor grainyhead-like 2 regulates the molecular composition of the epithelial apical junctional complex. Development. 2010;137:3835–3845. doi: 10.1242/dev.055483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikari A, Atomi K, Takiguchi A, Yamazaki Y, Miwa M, Sugatani J. Epidermal growth factor increases claudin-4 expression mediated by Sp1 elevation in MDCK cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honda H, Pazin MJ, Ji H, Wernyj RP, Morin PJ. Crucial roles of Sp1 and epigenetic modifications in the regulation of the CLDN4 promoter in ovarian cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21433–21444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh AB, Harris RC. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation differentially regulates claudin expression and enhances transepithelial resistance in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3543–3552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb-Rosteski JM, Kalischuk LD, Inglis GD, Buret AG. Epidermal growth factor inhibits Campylobacter jejuni-induced claudin-4 disruption, loss of epithelial barrier function, and Escherichia coli translocation. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3390–3398. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01698-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers MV, Manning HC, Coffey RJ, Liebler DC. Protein expression signatures for inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor mediated signaling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.015222. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terakado M, Gon Y, Sekiyama A, Takeshita I, Kozu Y, Matsumoto K, Takahashi N, Hashimoto S. The Rac1/JNK pathway is critical for EGFR-dependent barrier formation in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L56–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00159.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia D, Rahbar R, Fish EN. Interferon-inducible Stat2 activation of JUND and CLDN4: mediators of IFN responses. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:559–565. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amasheh M, Schlichter S, Amasheh S, Mankertz J, Zeitz M, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Quercetin enhances epithelial barrier function and increases claudin-4 expression in caco-2 cells. J Nutr. 2008;138:1067–1073. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.6.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Itallie C, Rahner C, Anderson JM. Regulated expression of claudin-4 decreases paracellular conductance through a selective decrease in sodium permeability. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1319–1327. doi: 10.1172/JCI12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohta A, Yang SS, Rai T, Chiga M, Sasaki S, Uchida S. Overexpression of human WNK1 increases paracellular chloride permeability and phosphorylation of claudin-4 in MDCKII cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:804–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rokkam D, Lafemina MJ, Lee JW, Matthay MA, Frank JA. Claudin-4 levels are associated with intact alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank JA, Briot R, Lee JW, Ishizaka A, Uchida T, Matthay MA. Physiological and biochemical markers of alveolar epithelial barrier dysfunction in perfused human lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L52–59. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00256.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell LA, Overgaard CE, Ward C, Margulies SS, Koval M. Differential effects of claudin-3 and claudin-4 on alveolar epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L40–49. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snyder JC, Zemke AC, Stripp BR. Reparative capacity of airway epithelium impacts deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:633–642. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0334OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue K, Oyamada M, Mitsufuji S, Okanoue T, Takamatsu T. Different changes in the expression of multiple kinds of tight-junction proteins during ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat ileum. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2006;39:35–45. doi: 10.1267/ahc.05048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreft ME, Sterle M, Jezernik K. Distribution of junction- and differentiation-related proteins in urothelial cells at the leading edge of primary explant outgrowths. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;125:475–485. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ewert P, Aguilera S, Alliende C, Kwon YJ, Albornoz A, Molina C, Urzua U, Quest AF, Olea N, Perez P, Castro I, Barrera MJ, Romo R, Hermoso M, Leyton C, Gonzalez MJ. Disruption of tight junction structure in salivary glands from Sjogren’s syndrome patients is linked to proinflammatory cytokine exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1280–1289. doi: 10.1002/art.27362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michikawa H, Fujita-Yoshigaki J, Sugiya H. Enhancement of barrier function by overexpression of claudin-4 in tight junctions of submandibular gland cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;334:255–264. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujita-Yoshigaki J. Analysis of changes in the expression pattern of claudins using salivary acinar cells in primary culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;762:245–258. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-185-7_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moriwaki K, Tsukita S, Furuse M. Tight junctions containing claudin 4 and 6 are essential for blastocyst formation in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 2007;312:509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanaspa MA, Andres-Hernando A, Rivard CJ, Dai Y, Berl T. Hypertonic stress increases claudin-4 expression and tight junction integrity in association with MUPP1 in IMCD3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15797–15802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agarwal R, D’Souza T, Morin PJ. Claudin-3 and claudin-4 expression in ovarian epithelial cells enhances invasion and is associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase-2 activity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7378–7385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boireau S, Buchert M, Samuel MS, Pannequin J, Ryan JL, Choquet A, Chapuis H, Rebillard X, Avances C, Ernst M, Joubert D, Mottet N, Hollande F. DNA-methylation-dependent alterations of claudin-4 expression in human bladder carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:246–258. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cunningham SC, Kamangar F, Kim MP, Hammoud S, Haque R, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Ashfaq R, Hustinx S, Heitmiller RE, Choti MA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD, Montgomery E. Claudin-4, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4, and stratifin are markers of gastric adenocarcinoma precursor lesions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:281–287. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halder SK, Rachakonda G, Deane NG, Datta PK. Smad7 induces hepatic metastasis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:957–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanada S, Maeshima A, Matsuno Y, Ohta T, Ohki M, Yoshida T, Hayashi Y, Yoshizawa Y, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M. Expression profile of early lung adenocarcinoma: identification of MRP3 as a molecular marker for early progression. J Pathol. 2008;216:75–82. doi: 10.1002/path.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hough CD, Sherman-Baust CA, Pizer ES, Montz FJ, Im DD, Rosenshein NB, Cho KR, Riggins GJ, Morin PJ. Large-scale serial analysis of gene expression reveals genes differentially expressed in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6281–6287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleinberg L, Holth A, Trope CG, Reich R, Davidson B. Claudin upregulation in ovarian carcinoma effusions is associated with poor survival. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landers KA, Samaratunga H, Teng L, Buck M, Burger MJ, Scells B, Lavin MF, Gardiner RA. Identification of claudin-4 as a marker highly overexpressed in both primary and metastatic prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:491–501. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lanigan F, McKiernan E, Brennan DJ, Hegarty S, Millikan RC, McBryan J, Jirstrom K, Landberg G, Martin F, Duffy MJ, Gallagher WM. Increased claudin-4 expression is associated with poor prognosis and high tumour grade in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2088–2097. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Chigurupati S, Agarwal R, Mughal MR, Mattson MP, Becker KG, Wood WH, 3rd, Zhang Y, Morin PJ. Possible angiogenic roles for claudin-4 in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1806–1814. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.19.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michl P, Barth C, Buchholz M, Lerch MM, Rolke M, Holzmann KH, Menke A, Fensterer H, Giehl K, Lohr M, Leder G, Iwamura T, Adler G, Gress TM. Claudin-4 expression decreases invasiveness and metastatic potential of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6265–6271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seckin Y, Arici S, Harputluoglu M, Yonem O, Yilmaz A, Ozer H, Karincaoglu M, Demirel U. Expression of claudin-4 and beta-catenin in gastric premalignant lesions. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsutsumi K, Sato N, Cui L, Mizumoto K, Sadakari Y, Fujita H, Ohuchida K, Ohtsuka T, Takahata S, Tanaka M. Expression of claudin-4 (CLDN4) mRNA in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:533–541. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lonardi S, Manera C, Marucci R, Santoro A, Lorenzi L, Facchetti F. Usefulness of Claudin 4 in the cytological diagnosis of serosal effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:313–317. doi: 10.1002/dc.21380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Facchetti F, Lonardi S, Gentili F, Bercich L, Falchetti M, Tardanico R, Baronchelli C, Lucini L, Santin A, Murer B. Claudin 4 identifies a wide spectrum of epithelial neoplasms and represents a very useful marker for carcinoma versus mesothelioma diagnosis in pleural and peritoneal biopsies and effusions. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:669–680. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0448-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Konecny GE, Agarwal R, Keeney GA, Winterhoff B, Jones MB, Mariani A, Riehle D, Neuper C, Dowdy SC, Wang HJ, Morin PJ, Podratz KC. Claudin-3 and claudin-4 expression in serous papillary, clear-cell, and endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee LY, Wu CM, Wang CC, Yu JS, Liang Y, Huang KH, Lo CH, Hwang TL. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 in gastric cancer and their relation to claudin-4 expression. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:515–521. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blanchard AA, Skliris GP, Watson PH, Murphy LC, Penner C, Tomes L, Young TL, Leygue E, Myal Y. Claudins 1, 3, and 4 protein expression in ER negative breast cancer correlates with markers of the basal phenotype. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:647–656. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kulka J, Szasz AM, Nemeth Z, Madaras L, Schaff Z, Molnar IA, Tokes AM. Expression of tight junction protein claudin-4 in basal-like breast carcinomas. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szasz AM, Nemeth Z, Gyorffy B, Micsinai M, Krenacs T, Baranyai Z, Harsanyi L, Kiss A, Schaff Z, Tokes AM, Kulka J. Identification of a claudin-4 and E-cadherin score to predict prognosis in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:2248–2254. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Milatz S, Krug SM, Rosenthal R, Gunzel D, Muller D, Schulzke JD, Amasheh S, Fromm M. Claudin-3 acts as a sealing component of the tight junction for ions of either charge and uncharged solutes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1798:2048–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daugherty BL, Ward C, Smith T, Ritzenthaler JD, Koval M. Regulation of heterotypic claudin compatibility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30005–30013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayashi D, Tamura A, Tanaka H, Yamazaki Y, Watanabe S, Suzuki K, Sentani K, Yasui W, Rakugi H, Isaka Y, Tsukita S. Deficiency of Claudin-18 Causes Paracellular H(+) Leakage, Up-regulation of Interleukin-1beta, and Atrophic Gastritis in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2011 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.040. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]