Abstract

The adoption of next-generation sequencing technologies has led to a remarkable shift in our understanding of the genetic landscape of follicular lymphoma. While the disease has been synonymous with the t(14;18), the prevalence of alterations in genes that regulate the epigenome has been established as a pivotal hallmark of these lymphomas. Giant strides are being made in unraveling the biological consequences of these alterations in tumorigenesis opening up new opportunities for directed therapies.

Keywords: : CREBBP, EP300, epigenetics, EZH2, follicular lymphoma, histone acetylation, histone methylation, KMT2D, noncoding RNA

Background

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is one of the most common non-Hodgkins’ lymphoma (NHL), with the tumor cells resembling germinal center (GC) B cells. Although the clinical course is typically considered indolent, it is punctuated by multiple relapses, demonstrates eventual refractoriness to standard therapies and about 30% of patients transform to aggressive lymphomas, usually diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). While the addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, to treatment regimens has markedly improved outcomes, it remains an incurable cancer [1,2] where patients with chemorefractory or transformed disease remain an area of unmet clinical need for which novel treatment strategies are warranted.

The primary genetic event in the classical model of FL pathogenesis is the reciprocal translocation t(14;18)(q32;q21) that leads to aberrant constitutive overexpression of the antiapoptotic BCL2 protein, occurring in 85–90% of patients [3,4]. While this translocation confers a survival advantage, several bodies of evidence suggest that it is insufficient on its own for lymphoma development [5–7] and secondary genetic hits are required for cellular transformation to FL [8,9]. Indeed, we now have a near complete catalogue of coding mutations and recognize that genetic alterations of several pathways, including multiple components of the epigenetic machinery, are a defining feature of FL pathogenesis (Table 1) [10–19].

Table 1. . The frequency and function of commonly mutated epigenetic genes in follicular lymphoma.

| Symbol | Gene name | Biological function | Oncogenic alteration | Mutation frequency (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KMT2D |

Lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2D |

H3K4 methylase: activator |

Loss of function |

76–89 |

[10,12,14] |

|

CREBBP |

CREB binding protein |

H3K27 and H3K18 acetylase: activator |

Mutations cluster in histone acetyltransferase domain. Loss of function† |

33–68 |

[10–12,14] |

|

EP300 |

E1A binding protein p300 |

H3K27 and H3K18 acetylase: activator |

Loss of function† |

9 |

[10–12,14] |

|

EZH2 |

Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit |

H3K27 methylase: repressor |

Hotspot mutations at Y641, A682, and A692. Gain of function† |

7–27 |

[15–16,20–21] |

|

HIST1H1B-E |

Histone H1 family genes B-E |

Linker histones |

To be elucidated |

28 |

[12,14,22] |

| ARID1A | AT rich interactive domain 1A (SWI-like) | Nucleosome remodeling | To be elucidated | 9–11 | [12,14,22] |

†Also subject to copy number changes.

Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation play a critical role in normal cellular processes. These epigenetic modifications display dynamic features that involve the addition or removal of chemical groups to DNA or histones and are catalyzed by families of enzymes known as ‘writers’ or ‘erasers’ of the epigenetic code. Another group of proteins (‘readers’) are recruited to specific regions of the genome through recognition of the modifications created by ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’, and include proteins that are able to further alter the chromatin state and subsequently regulate the expression of target genes. A more detailed account of the mechanisms through which epigenetic regulators and modifications regulate gene expression is beyond the scope of this review, and have been extensively discussed elsewhere [23–25]. In this review, we focus attention on FL, the potential functional consequences of alterations of these regulators of the epigenome and discuss the latest progress in harnessing this knowledge for successful epigenetic targeting.

Epigenetic landscape of FL

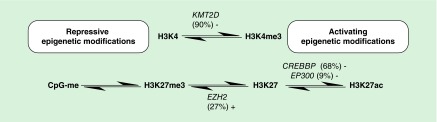

In FL, epigenomic mutations predominantly target the histone methyltransferases KMT2D (90%) and EZH2 (25%), as well as the histone acetyltransferases CREBBP (30–60%) and EP300 (9%), with almost 80% of cases having co-occurring mutations [10–19]. These somatic mutations are predominantly inactivating, with the exception of EZH2 [10–11,20–21,26] where mutations cluster to 3 amino acid positions (Y641, A682 and A692) located within its catalytic SET domain. These ‘writers’ of the histone code play a central role in regulating gene expression by modifying two key lysine residues; the histone 3 lysine position 4 (H3K4; KMT2D) and histone 3 lysine position 27 (H3K27; EZH2, CREBBP and EP300) marks, while seemingly sparing other residues (Figure 1) [25]. These aberrations are complemented by mutations in a plethora of additional genes that have received less attention, including mutations of linker and core histones which reduce their binding affinity for chromatin and truncating mutations of the chromatin remodeling complex ARID1A which increases genomic instability, all of which lead to some form of epigenetic chaos in support of malignant transformation [12,22].

Figure 1. . A model for how mutations of epigenetic regulators can lead to dysregulation of H3K4 and H3K27 modification in follicular lymphoma.

Loss of function (-) and gain of function (+) mutations confer a repressed chromatin state and alongside promoter hypermethylation (CpG-me) may act to repress gene expression.

Although the precise genes and cellular pathways dysregulated by these alterations are not fully characterized, we can make several assumptions from the evidence currently available. Firstly, the prevalence of co-occurring ‘epimutations’ suggests a combinatorial, rather than truly independent or additive mechanism of action. Secondly, the temporal sequencing of sequential FL tumors has highlighted that mutations in KMT2D and CREBBP represent early oncogenic events, providing compelling evidence for their role in forming the founder ‘common progenitor cell’ population (CPC) [12–13,19]. This putative population is postulated to evade chemotherapy and act as a reservoir that seeds each relapse and transformation event, with effective targeting of this population a potential route to a cure [27]. In addition, the incorporation of these epigenetic mutations has led to improved prognostication tools with a recent model termed the m7-FLIPI combining clinical factors with mutations in seven genes including CREBBP, ARID1A, EP300 and EZH2, where EZH2 mutations were strongly associated with good risk disease [28].

From a therapeutic perspective, the opportunities to exploit the inherent plasticity of epigenetic changes are manifold. While epigenetic therapies such as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) have previously been evaluated in FL, results were overall disappointing and predated our current knowledge of the epigenomic landscape of this malignancy [29], which may provide a rationale to guide therapy in accordance to patients’ underlying (epi)genetic profiles. It is also important to recognize that epigenomic alterations are not restricted to FL but occur in almost every type of cancer, highlighting their emerging role as a hallmark of cancer [30]. Interestingly, the (epi)genetic landscape of FL overlaps significantly with the related aggressive subtype, germinal center B-cell DLBCL (GCB-DLBCL), with the epigenetic basis of DLBCL the subject of a recent review [31]. However, FL appears to be a rather unique malignancy with epimutations arising in nearly every patient, and therefore may represent a valuable model to examine how epigenetic perturbations drive cancer in general.

Histone modifications

In FL, one postulates that the prevailing consequence of the mutations in the histone-modifying enzymes is a shift in the equilibrium towards aberrant repression of gene transcription brought about by loss of active marks of transcription, catalyzed by the ‘writers’ KMT2D (H3K4me3) and CREBBP/EP300 (H3K27ac), and increase in the repressive mark H3K27me3 through mutations in EZH2 (Figure 1). It seems implausible that these mutations are acting alone but must do so in a co-ordinated manner, working in concert to impact expression of key regulators of B-cell homeostasis. Mechanistic insight as to how these aberrations promote lymphomagenesis is the subject of ongoing work, with an initial focus on the role of individual components, with EZH2 the best characterized presently.

EZH2 is the SET domain-containing catalytic subunit of PRC2, which catalyses methylation of the H3K27 residue. It has been recognized for some time that EZH2 plays a controlling role in co-ordinating gene expression in stem cells through the formation of ‘bivalent’ or ‘poised’ genes, which are marked by both the active H3K4me3 and the repressive H3K27me3 mark, allowing for exquisite control of gene expression during differentiation [32,33]. Morin et al. were the first to report mutations of this histone methyltransferase in GC lymphomas, leading to an increase in H3K27me3 [15,20–21]. The expression of EZH2 is undetectable in resting B cells, but rapidly increases as cells enter the GC reaction, and falls following exit of the GC [34,35]. It has also been implicated in control of B-cell proliferation since silencing of EZH2 leads to cell cycle arrest at the G1/S transition and expression of tumor suppressor genes including CDKN1A, [35]. Critically, EZH2 was found to be a cardinal regulator of the GC phenotype by repressing the expression of known regulators of B cell differentiation such as PRDM1 and IRF4 through the deposition of H3K27me3 upon entry into the GC [36,37]. Furthermore, mutant Ezh2 reinforces the formation of bivalent genes within the GC and permanently suppresses certain Ezh2 target genes, ‘locking’ cells into the GC reaction and preventing terminal differentiation [37]. Similarly, conditional expression of mutant Ezh2 within lymphocytes induced GC hyperplasia, albeit the mutation was insufficient to induce lymphomagenesis on its own. However, conditional expression of mutant Ezh2 accentuated lymphoma development in Eμ-Myc and vav-Bcl2 mice, suggesting that while epigenetic mutations might be insufficient to induce lymphomagenesis in isolation, they co-operate with additional oncogenic lesions to promote malignant transformation [37,38].

In parallel with these genetic discoveries, there has been a rapid development of inhibitors targeting EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity, which are demonstrating promising results in both in vitro and in vivo models [39,40]. Moreover, there is encouraging new data supporting a role for these inhibitors in solid cancers, where oncogenic and synthetic lethal dependencies on EZH2 can be exploited [41–43]. At present, three compounds have proceeded to early phase clinical trials in patients; Epizyme-E7438 (NCT01897571) [44], Constellation Pharmaceuticals-CPI-1205 (NCT02395601) [45] and the GlaxoSmithKline compound GSK2816126 (NCT02082977) [46], and although it is too early to draw firm conclusions regarding efficacy, emerging Phase I data suggest a potential role in EZH2 wildtype tumors [47].

KMT2D is a member of the KMT2 family of methyltransferases, which promote transcription and chromatin accessibility through methylation of H3K4, and have been implicated in a wide range of malignancies [48]. The majority of genetic alterations are predicted to lead to truncation of the protein and presumably repress gene expression through decreased methylation of H3K4. Recent studies support a role for KMT2D in regulating cell type-specific enhancer activity through monomethylation of H3K4 [48–50] and it is, therefore, reasonable to speculate that these inactivating KMT2D mutations in FL may well disrupt enhancer activation impacting on key B-cell networks. Suitable in vitro and in vivo conditional models will be required to address the question of the mechanistic role of KMT2D in FL, since homozygous deletions of Kmt2d are embryonically lethal [49], while heterozygous germline mutations are associated with the childhood developmental disorder Kabuki syndrome [51]. There is no compelling evidence to suggest that these patients are predisposed to lymphoma, suggesting that the most informative experiments will be those where KMT2D function is explored within the context of other recurring gene mutations.

Although research into the function of CREBBP and EP300 in normal GC B cells and FL is still in its infancy, inactivating genetic aberrations are predicted to contribute to a repressed gene expression state through decreased acetylation of H3K27 (H3K27ac) and other target proteins. Homozygous null mutations in either Crebbp or Ep300, or compound heterozygosity, result in early embryonic death [52,53]. Recent in vitro studies reveal that CREBBP mutants have reduced ability to acetylate the proteins, p53 and BCL6, with acetylation enhancing the action of p53 and repressing that of BCL6, in keeping with its presumed role as a tumor suppressor [11]. More recently, Green et al. demonstrated that CREBBP-mutated FL tumors were linked to a diminished antigen presentation gene signature and downregulation of MHC Class II surface expression on tumor cells where corresponding tumors profoundly reduced the proliferation capacity of tumor-infiltrating T cells, collectively suggesting that CREBBP mutations may in some way promote immune-surveillance escape mechanisms [14].

DNA methylation

While aberrant DNA methylation is a feature of all cancers, it is only in myeloid malignancies where the use of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTi) has demonstrated efficacy [54,55]. Despite this, hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes has been demonstrated in numerous studies including FL [56,57], with a significant overlap noted between hypermethylated CpGs and PRC2 target genes in embryonic stem cells [58]. Although initial reports suggested conservation of methylation profiles between paired pre- and post-transformation samples [58], the introduction of higher resolution platforms, suggests measurable differences in relapsed and more aggressive tumors [59,60]. Recent studies by Clozel et al. propose a paradigm shifting change in how epigenetic therapies may be used to greatest effect; in a study of DLBCL, low-dose DNMTi exposure was used as a means of sensitizing chemoresistant tumors to doxorubicin through increased expression of a restricted number of genes including SMAD1 and demonstrated that combination of pretreatment with 5-azacitidine followed by chemoimmunotherapy recapitulated this observation in a Phase I clinical trial [61].

Noncoding regulatory regions

Genetic studies of FL, along with the vast majority of cancer studies to date, have focused on the protein-coding region constituting less than 2% of the entire human genome. Functional noncoding elements including promoters and enhancers, located proximal or distal to protein-coding genes respectively and which regulate gene expression through transcription factor (TF) binding, have for the most part been ignored. Additionally, noncoding RNAs including miRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) represent equally important new players responsible for fine-tuning gene expression alongside DNA- and histone-based epigenetic modifications. Indeed, the availability of whole genome sequencing has opened the door to a more rigorous exploration of the noncoding genome for the first time highlighted with the discovery of TERT promoter mutations in melanoma and other solid cancers, resulting in increased expression of the oncogenic TERT [62–64]. The first major effort to examine the FL noncoding genome, alongside several other B-cell lymphomas, was recently performed by Mathelier et al. where they focused on overlaying somatic noncoding mutations with publically available TF-binding sites and testing the expression of proximal genes in order to identify cis-regulatory mutations within promoters [65]. This approach led to the identification of genes with altered expression as a consequence of disrupted TF binding including several with known key roles in lymphomagenesis. Enhancer profiling by Koues et al. in FL demonstrated that FL tumors not only suppress specific enhancers so as to shed nonessential components of the GC transcriptional circuitry but additionally hijacked critical enhancers from other lineages to acquire specific advantageous tumorigenic functions [66]. Taken together, these recent studies highlight the contribution of the noncoding genome and earmark the importance of this exciting new chapter in FL pathogenesis.

Conclusion & future perspective

Advances in the molecular characterization of FL have yielded important insights into the genetic basis of this malignancy, categorically placing epigenetic dysregulation at the center of germinal center lymphoma pathogenesis. While detailed functional studies are underway to decipher how each of these genetic attributes contributes independently to the development of FL, combinatorial experimental systems are essential to model the human tumors and delineate how the complex interplay between these alterations leads to lymphomagenesis and establishment of the CPC in FL. In parallel, the supporting role of the noncoding genome in gene regulation represents a new area of exploration requiring systematic integrated genomic, epigenomic and transcriptomic approaches to further enhance our understanding of the personality of this disease.

Altogether, opportunities are now presenting themselves to translate knowledge of the molecular landscape into novel epigenetically targeted therapies that directly or indirectly abrogate the epigenetic alterations in FL and this has been exemplified by early phase clinical trials with EZH2 inhibitors. On a cautious note, as epigenetic changes can lead to broad global gene expression changes, we must carefully devise therapies that limit their effects to the malignant tumor population and restrict off-target effects. Ultimately, it is anticipated that the future clinical management of patients will move away from our current ‘one size fits all’ approach and towards a much more stratified strategy where we would treat patients on the basis of each of their underlying tumor’s (epi)genetic signature. The ability to target the very essence of the tumor may invariably make FL a potentially curable malignancy or at least improve the outcomes for the poorer risk patients.

Executive summary.

Epigenetic landscape of follicular lymphoma

Epigenetic dysregulation has emerged as a key feature in the pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma (FL).

Mutations that modify histones are the most frequently mutated in FL, present in over 90% of cases.

Clonal evolution studies suggest that these mutations occur early in lymphomagenesis.

The mutations are predicted to result in a global pattern of gene repression and center on two key lysine residues, H3K4 and H3K27.

Histone modifications

EZH2 mutations occur in the catalytic SET domain (Y641, A682, A692) and are gain-of-function mutations, resulting in an increase of H3K27me3, a repressive gene transcription mark.

EZH2 is a key regulator of the GC reaction and acts to repress terminal B-cell differentiation genes.

The function of KMT2D, CREBBP and EP300 mutations in FL has yet to be fully elucidated but are predicted to decrease H3K4 methylation and H3K27 acetylation respectively.

DNA methylation

Tumor suppressor genes are frequently hypermethylated in FL, many of which are also targets for repression by the PRC2 complex.

DNA methyltransferase inhibitors have been shown to sensitize chemoresistant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma to chemotherapy, highlighting the need for similar studies in FL.

Noncoding regulatory regions

There is emerging evidence to suggest that mutations targeting transcription factor binding and enhancer dysregulation contribute to the development of FL.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

J Fitzgibbon is supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant (15968). S Araf is a recipient of a Cancer Research UK Clinical Research Fellowship. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues (4th Edition) IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kridel R, Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122(10):3424–3431. doi: 10.1172/JCI63186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsujimoto Y, Gorham J, Cossman J, Jaffe E, Croce CM. The t(14;18) chromosome translocations involved in B-cell neoplasms result from mistakes in VDJ joining. Science. 1985;229(4720):1390–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.3929382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss LM, Warnke RA, Sklar J, Cleary ML. Molecular analysis of the t(14;18) chromosomal translocation in malignant lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;317(19):1185–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711053171904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roulland S, Lebailly P, Lecluse Y, Heutte N, Nadel B, Gauduchon P. Long-term clonal persistence and evolution of t(14;18)-bearing B cells in healthy individuals. Leukemia. 2006;20(1):158–162. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mcdonnell TJ, Korsmeyer SJ. Progression from lymphoid hyperplasia to high-grade malignant lymphoma in mice transgenic for the t(14; 18) Nature. 1991;349(6306):254–256. doi: 10.1038/349254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Limpens J, Stad R, Vos C, et al. Lymphoma-associated translocation t(14;18) in blood B cells of normal individuals. Blood. 1995;85(9):2528–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sungalee S, Mamessier E, Morgado E, et al. Germinal center re-entries of BCL2-overexpressing B cells drive follicular lymphoma progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124(12):5337–5351. doi: 10.1172/JCI72415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. Germinal centres and B cell lymphoma genesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15(3):172–184. doi: 10.1038/nri3814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476(7360):298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An important early study that recognized the recurrent nature of epigenetic mutations in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- 11.Pasqualucci L, Dominguez-Sola D, Chiarenza A, et al. Inactivating mutations of acetyltransferase genes in B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2011;471(7337):189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature09730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Another early study which reported genetic alterations in CREBBP and EP300 as frequent occurrences in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and demonstrated the functional deficiency in acetylation of CREBBP mutants.

- 12.Okosun J, Bodor C, Wang J, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies recurrent mutations and evolution patterns driving the initiation and progression of follicular lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 2014;46(2):176–181. doi: 10.1038/ng.2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green MR, Gentles AJ, Nair RV, et al. Hierarchy in somatic mutations arising during genomic evolution and progression of follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(9):1604–1611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green MR, Kihira S, Liu CL, et al. Mutations in early follicular lymphoma progenitors are associated with suppressed antigen presentation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112(10):E1116–E1125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501199112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morin RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat. Genet. 2010;42(2):181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first study to describe recurrent mutations in the histone methyltransferase EZH2 in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- 16.Bodor C, Grossmann V, Popov N, et al. EZH2 mutations are frequent and represent an early event in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2013;122(18):3165–3168. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodor C, O’Riain C, Wrench D, et al. EZH2 Y641 mutations in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia. 2011;25(4):726–729. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan RJ, Nitta M, Borger D, et al. EZH2 codon 641 mutations are common in BCL2-rearranged germinal center B cell lymphomas. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e28585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasqualucci L, Khiabanian H, Fangazio M, et al. Genetics of follicular lymphoma transformation. Cell Rep. 2014;6(1):130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yap DB, Chu J, Berg T, et al. Somatic mutations at EZH2 Y641 act dominantly through a mechanism of selectively altered PRC2 catalytic activity, to increase H3K27 trimethylation. Blood. 2011;117(8):2451–2459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Reported the gain of function phenotype of the EZH2 Y641 mutation seen in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

- 21.Sneeringer CJ, Scott MP, Kuntz KW, et al. Coordinated activities of wild-type plus mutant EZH2 drive tumor-associated hypertrimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27) in human B-cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(49):20980–20985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Another study which reported the gain of function phenotype of the EZH2 Y641 mutation.

- 22.Li H, Kaminski MS, Li Y, et al. Mutations in linker histone genes HIST1H1 B, C, D, and E; OCT2 (POU2F2); IRF8; and ARID1A underlying the pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123(10):1487–1498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen H, Laird PW. Interplay between the cancer genome and epigenome. Cell. 2013;153(1):38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plass C, Pfister SM, Lindroth AM, Bogatyrova O, Claus R, Lichter P. Mutations in regulators of the epigenome and their connections to global chromatin patterns in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013;14(11):765–780. doi: 10.1038/nrg3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21(3):381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasqualucci L, Trifonov V, Fabbri G, et al. Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 2011;43(9):830–837. doi: 10.1038/ng.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green MR, Alizadeh AA. Common progenitor cells in mature B-cell malignancies: implications for therapy. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2014;21(4):333–340. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastore A, Jurinovic V, Kridel R, et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okosun J, Packham G, Fitzgibbon J. Investigational epigenetically targeted drugs in early phase trials for the treatment of haematological malignancies. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2014;23(10):1321–1332. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.923402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(11):1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Y, Melnick A. The epigenetic basis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin. Hematol. 2015;52(2):86–96. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An in-depth review of current knowledge on the mechanisms of epigenetic dysregulation in the related lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- 32.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125(2):315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gan Q, Yoshida T, Mcdonald OG, Owens GK. Concise review: epigenetic mechanisms contribute to pluripotency and cell lineage determination of embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(1):2–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Galen JC, Dukers DF, Giroth C, et al. Distinct expression patterns of polycomb oncoproteins and their binding partners during the germinal center reaction. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34(7):1870–1881. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velichutina I, Shaknovich R, Geng H, et al. EZH2-mediated epigenetic silencing in germinal center B cells contributes to proliferation and lymphoma genesis. Blood. 2010;116(24):5247–5255. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caganova M, Carrisi C, Varano G, et al. Germinal center dysregulation by histone methyltransferase EZH2 promotes lymphoma genesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123(12):5009–5022. doi: 10.1172/JCI70626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beguelin W, Popovic R, Teater M, et al. EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(5):677–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Important in depth analysis of the functional role of EZH2 in germinal center B cells, uncovering the role of EZH2 in preventing terminal differentiation of B cells.

- 38.Berg T, Thoene S, Yap D, et al. A transgenic mouse model demonstrating the oncogenic role of mutations in the polycomb-group gene EZH2 in lymphoma genesis. Blood. 2014;123(25):3914–3924. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-473439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mccabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492(7427):108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • One of the first reports of a selective inhibitor of EZH2 with specificity and potency in vitro and in vivo for EZH2 mutant non-Hodgkins’ lymphomas.

- 40.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, et al. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8(11):890–896. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Another study describing a selective inhibitor of EZH2 with potent in vitro and in vivo activity for EZH2 mutant non-Hodgkins’ lymphomas.

- 41.Bitler BG, Aird KM, Garipov A, et al. Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nat. Med. 2015;21(3):231–238. doi: 10.1038/nm.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fillmore CM, Xu C, Desai PT, et al. EZH2 inhibition sensitizes BRG1 and EGFR mutant lung tumours to TopoII inhibitors. Nature. 2015;520(7546):239–242. doi: 10.1038/nature14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ, et al. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(19):7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clinical Trial Database: NCT02395601. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02395601

- 45.Clinical Trial Database: NCT01897571. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01897571

- 46.Clinical Trial Database: NCT02082977. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02082977

- 47.Ribrag V, Soria J, Reyderman L, et al. 13th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma. Lugano, Switzerland: 2015. Phase 1 study of E7438 (EPZ-6438), an enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitor: dose determination and preliminary activity in non-hodgkin lymphoma; pp. 17–20. Presented at. June. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rao RC, Dou Y. Hijacked in cancer: the KMT2 (MLL) family of methyltransferases. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15(6):334–346. doi: 10.1038/nrc3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JE, Wang C, Xu S, et al. H3K4 mono- and di-methyltransferase MLL4 is required for enhancer activation during cell differentiation. eLife. 2013;2:e01503. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo C, Chen LH, Huang Y, et al. KMT2D maintains neoplastic cell proliferation and global histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation. Oncotarget. 2013;4(11):2144–2153. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2010;42(9):790–793. doi: 10.1038/ng.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oike Y, Takakura N, Hata A, et al. Mice homozygous for a truncated form of CREB-binding protein exhibit defects in hematopoiesis and vasculo-angiogenesis. Blood. 1999;93(9):2771–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao TP, Oh SP, Fuchs M, et al. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell. 1998;93(3):361–372. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, Phase III study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, Phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30(21):2670–2677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alhejaily A, Day AG, Feilotter HE, Baetz T, Lebrun DP. Inactivation of the CDKN2A tumor-suppressor gene by deletion or methylation is common at diagnosis in follicular lymphoma and associated with poor clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1676–1686. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Giachelia M, Bozzoli V, D’Alò F, et al. Quantification of DAPK1 promoter methylation in bone marrow and peripheral blood as a follicular lymphoma biomarker. J. Mol. Diagn. 2014;16(4):467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Riain C, O’Shea DM, Yang Y, et al. Array-based DNA methylation profiling in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1858–1866. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loeffler M, Kreuz M, Haake A, et al. Genomic and epigenomic co-evolution in follicular lymphomas. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):456–463. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De S, Shaknovich R, Riester M, et al. Aberration in DNA methylation in B-cell lymphomas has a complex origin and increases with disease severity. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clozel T, Yang S, Elstrom RL, et al. Mechanism-based epigenetic chemosensitization therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(9):1002–1019. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, Kryukov GV, Chin L, Garraway LA. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):957–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339(6122):959–961. doi: 10.1126/science.1230062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fredriksson NJ, Ny L, Nilsson JA, Larsson E. Systematic analysis of noncoding somatic mutations and gene expression alterations across 14 tumor types. Nat. Genet. 2014;46(12):1258–1263. doi: 10.1038/ng.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathelier A, Lefebvre C, Zhang AW, et al. Cis-regulatory somatic mutations and gene-expression alteration in B-cell lymphomas. Genome Biol. 2015;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0648-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koues OI, Kowalewski RA, Chang LW, et al. Enhancer sequence variants and transcription-factor deregulation synergize to construct pathogenic regulatory circuits in B-cell lymphoma. Immunity. 2015;42(1):186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first study to investigate the role of enhancer dysregulation in follicular lymphoma pathogenesis.