Abstract

Background

Sexual dysfunction is a frequently reported consequence of rectal/anal cancer treatment for female patients.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to conduct a small randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of a telephone-based, four-session Cancer Survivorship Intervention-Sexual Health (CSI-SH).

Methods

Participants (N = 70) were stratified by chemotherapy, stoma, and menopause statuses before randomization to CSI-SH or assessment only (AO). Participants were assessed at baseline, 4 months (follow-up 1), and 8 months (follow-up 2).

Results

The intervention had medium effect sizes from baseline to follow-up 1, which decreased by follow-up 2. Effect sizes were larger among the 41 sexually active women. Unadjusted means at the follow-ups were not significantly different between the treatment arms. Adjusting for baseline scores, demographics, and medical variables, the intervention arm had significantly better emotional functioning at follow-ups 1 and 2 and less cancer-specific stress at follow-up 1 compared to the AO arm.

Conclusion

The data supported the hypothesized effects on improved sexual and psychological functioning and quality of life in CSI-SH female rectal/anal cancer survivors compared to the AO condition.

Condensed Abstract

This pilot study (N = 70) of CSI-SH supported the impact of this intervention on sexual and psychological functioning and quality of life on rectal and anal cancer survivors compared with an AO condition. However, intervention effects were stronger at follow-up 1 as compared to follow-up 2 and were stronger for sexually active women.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Women may benefit from a brief, four-session, sexual health intervention after treatment from rectal and anal cancer.

Keywords: Sexual dysfunction, Female, Rectal cancer, Anal cancer, Psychological distress

Advances in screening guidelines, awareness, and treatment have resulted in a decrease in female colorectal cancer mortality throughout the past decade [1]. Ensuring the long-term health and quality of life (QoL) of survivors has thus become an increasing priority. Sexual dysfunction is a frequently reported consequence of rectal and anal cancer treatment for female patients. Nevertheless, sexual functioning and satisfaction are often not addressed by providers and are domains for which empirically based, accessible treatments are lacking [2–4].

Treatment for rectal/anal cancer may involve surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation. Given treatments’ anatomical proximity to the genital area, female sexual functioning is often negatively affected [5, 6]. Post-treatment sexual dysfunction is significant, with studies reporting prevalence rates between 19 and 62 % [7]. Indeed, a recent literature review reported that 30–40 % of patients who were sexually active prior to treatment became sexually inactive post-treatment [8]. Panjari and colleagues’ comprehensive literature review on the impact of rectal cancer treatment on female patients’ QoL ultimately indicated that over 60 % of women had varying degrees of sexual dysfunction [4]. Chemotherapy and pelvic radiation, surgery which is done near the vaginal area, and, particularly, the combination of radiation therapy plus surgery can lead to estrogen deprivation, damaged nerves, and, in some cases, a stoma. Early menopause, dryness, and narrowing of the vagina can, in turn, be associated with pain, lack of vaginal lubrication, decreased arousal, discomfort, and lack of orgasm. Psychological side effects can also leading to decreased sexual functioning and satisfaction [4, 6–9]. In addition to sexual functioning and satisfaction changes, treatment side effects also include gastrointestinal, bladder, and bowel issues such as incontinence and diarrhea which can also be embarrassing and inhibiting and reduce QoL [1, 7, 9]. The majority of patients report higher QoL once treatment is complete, although post-treatment sexual functioning does not show an improvement as steep as that of QoL [10–13]. In fact, sexual functioning scores appear to remain low across the time following treatment, relative to most QoL scores [1, 3]. Female rectal and anal cancer survivors thus have unique needs from the impact of the disease and treatment that must be specifically addressed [2, 5, 6].

The relationship between sexual functioning and psychosocial outcomes is complex, with little corresponding research in rectal cancer patients. Hendren and colleagues reported post-surgery rectal cancer patients’ sexual functioning to be impacted by both psychological and physical factors, including body image, fatigue, non-sexual pain, nausea, lubrication, libido, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia [5]. Studies of other oncology populations have reported mixed findings [10, 12–18]. Sexual functioning is rarely the focus of the patient-doctor interaction and is infrequently addressed by physicians, who may have little training in discussing this issue. Thus, dysfunction often persists despite most patients’ desire for more communication around sexual issues [19–21].

To date, no empirically based intervention has been developed to address the unique sexual health needs of rectal cancer patients. However, Brotto and colleagues found that gynecologic cancer patients’ self-report of sexual response (lubrication, genital throbbing) significantly improved in an intervention consisting of educational strategies and sensate focus techniques [22]. Jefford and colleagues reported that, in a pilot study assessing the impact of a nurse-led post-treatment support intervention for male and female colorectal cancer patients, the inclusion of support information on sexuality and relationship problems might reduce distress levels and improve QoL (though sexual functioning was not the focus of this study) [23]. Overall, studies show that non-hormonal and educational methods of therapy can improve vaginal health and sexual functioning in female cancer survivors. Educating women on vaginal lubricants, moisturizers, and dilator use can improve sexual functioning and related QoL [2, 24]. However, many women are unaware of these simple therapies.

We report the development and pilot testing of the Cancer Survivorship Intervention-Sexual Health (CSI-SH) developed and tested at an Eastern US comprehensive cancer center and an Eastern US general hospital. The CSI-SH addressed sexual dysfunction and sexual health concerns in female rectal/anal cancer survivors. This four-session education-focused intervention was conducted primarily via telephone and developed based on the input of survivors (via one focus group and seven individual interviews), clinical expertise, and prior research (most notably a sexual counseling intervention for couples after treatment for localized prostate cancer conducted by Schover and colleagues, a vaginal health educational intervention for female cancer patients developed by Carter and colleagues [25], and a cognitive behavior therapy intervention developed by DuHamel and colleagues [26] for cancer survivors after hemopoietic stem cell transplant which including homework such as identifying unhelpful thoughts and communication strategies which were revised for this pilot). The interventionist followed the manual outlining the four sessions, and the study participants received their corresponding version of the manual in the mail. Women were also mailed a gift-wrapped package which they were instructed to not open until directed to do so by the interventionist. This package contained the dilators. Each session ended with a review of the homework assignments, and for the last session, this included continuing the study strategies [26]. The current study presents results from a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the efficacy of the CSI-SH to an assessment-only (AO) control condition. The purpose of this pilot RCT was to generate preliminary efficacy and effect size estimates for short-term (4 months) and long-term (8 months) endpoints to aid the planning of a larger-scale RCT. Our primary hypothesis was that CSI-SH participants would show improved sexual functioning compared to an AO control condition. Second, as compared to the AO condition, the intervention would lead to survivors’ (1) reduced cancer-specific distress, (2) reduced general distress, and (3) increased QoL.

Methods

Participants

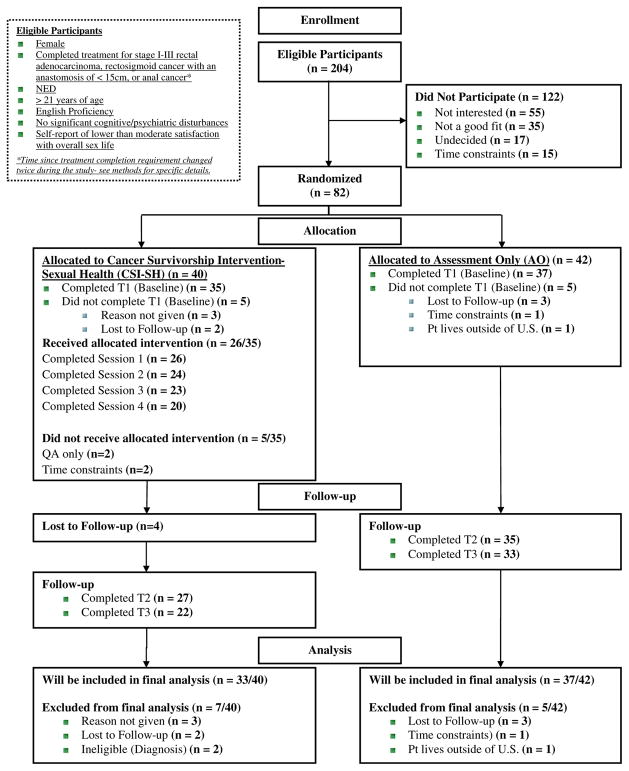

The initial power analysis indicated that a sample of 32 participants per group had 80 % power to detect a between-group effect size for difference in means of 0.71, at a two-sided significance level of 0.05 [27]. This pilot study focused on providing estimates of means and effect sizes for this intervention. Potential participants were identified by reviewing the medical centers’ colorectal medical and surgical clinic lists and by query of the institutional databases and then screened for eligibility through review of the electronic medical records. A list of potentially eligible patients was sent to oncologists for their review prior to a woman being sent a study invitation letter or approached in-clinic. Two hundred four participants were deemed eligible based on medical history and approached for participation. One hundred twenty-two participants did not participate due to lack of interest (n = 55), not feeling that the study was a good fit (n = 35), being undecided (n = 17), and time constraints (n = 15). Eighty-two women provided informed consent and were randomized (from Dec 10, /2008, to Oct 12, 2011, at the comprehensive cancer center and Feb 13, 2009, to Oct 25, 2010, at the general hospital). Seventy were included in the analyses (see consort Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort chart of the study

Inclusion criteria were the following: female and having completed treatment for stage I–III rectal adenocarcinoma, rectosigmoid cancer with an anastomosis of ≤15 cm, or anal cancer (the inclusion of anal cancer to the eligibility criteria was made on Jan 26, 2010). Treatment procedures for eligibility included radiation and/or surgery for rectal and rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma or radiation and/or chemotherapy for anal cancer. Participants were required to have no current evidence of disease, be ≥21 years of age, communicate proficiently in English, and have no significant cognitive/psychiatric disturbances. We initially included patients ≥2 years post-treatment for rectal cancer due to a competing protocol that was recruiting patients within 2 years of treatment completion (recruitment dates: Dec 10, 2008–Aug 26, 2009). When the competing protocol ended, criteria were shifted to consider any women post-treatment for rectal cancer (recruitment dates Sept 23, 2009–Jan 26, 2010). Then, in January 2010, we changed the criteria to include patients who were at least 1 year post-treatment due to clinical recommendations from medical professionals on the research team. Patients reporting higher than moderate satisfaction (i.e., a score of 5) with their overall sexual life on a pre-screening questionnaire (“Over the past 4 weeks, how satisfied have you been with your overall sexual life?” 5 = very satisfied, 4 = moderately satisfied, 3 = about equally satisfied and dissatisfied, 2 = moderately dissatisfied, 1 = very dissatisfied) were excluded.

Study design and procedures

Within 2 weeks of consent, participants completed baseline questionnaires. Women were then grouped using a stratified block design based on the following: (1) having a stoma, (2) having had chemotherapy, and (3) being post-menopausal. Within the stratum, women were randomized (with equal probability) to receive either the Cancer Survivorship Intervention-Sexual Health (CSI-SH) or the AO arm.

CSI-SH participants received four 1-h individual sessions. To be maximally flexible in the context of travel and time constraints, some women completed all sessions by phone (n = 14; 54 %) and some had mixed phone and in-person sessions (n = 12; 46 %). No patients completed all sessions in person. All sessions were facilitated by a trained mental health professional, and the professional was consistent across the sessions. Participants had follow-up booster phone calls approximately 1 week after each of the first three individual sessions. Participants completed outcome assessments at baseline and at 4 (follow-up 1) and 8 months (follow-up 2) post-baseline (see Table 1 for timeline). If randomized to the AO group, participants only completed the study assessments. Assessments for the AO participants were timed to be yoked with assessment timing for the CSI-SH participants. The intervention was offered to AO group participants after completion of their assessments. Assessments took approximately 45 min to complete by telephone with a research assistant who was blinded to the treatment condition. Participants were reimbursed $10 for each assessment.

Table 1.

Study timeline

| Group | Time point | Intervention | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSI-SH and AO | Baseline | Assessment time point 1 | |

| CSI-SH | 2-week post-BL | Session 1 | 1-h session on goals and issues with cancer treatment and sexuality |

| 1-week post-session 1 | Booster call 1 | Review of session 1 topics and HW; | |

| Session 2 | 1-h session on rehabilitation tools and techniques | ||

| 1-week post-session 2 | Booster call 2 | Review of session 2 HW; | |

| Session 3 | 1-h session on mind-body connection methods | ||

| 1-week post-session 3 | Booster call 3 | Review of session 3 HW; | |

| Session 4 | 1-h session on concerns and reflection of intervention | ||

| CSI-SH and AO | Follow-up 1 (4 months post-BL) | Assessment time point 2 | |

| CSI-SH and AO | Follow-up 2 (8 months post-BL) | Assessment time point 3 |

CSI-SH Cancer Survivorship Intervention-Sexual Health study arm, AO assessment-only study arm

Intervention

The intervention was based on prior research that examined the sexual health of rectal and other female cancer patients, investigators’ clinical and intervention research experiences, and feedback from rectal cancer survivors via one focus group and qualitative interviews. Each session included homework assignments as well as booster calls between sessions to promote adherence and to help participants implement strategies learned during sessions. The same therapist conducted all sessions with the same participant (for details about the provider or participant manual, please contact the corresponding author). The study was registered with the office of clinical trials on Jul 7, 2008 (NCT00712751), and was approved by the institutional review board.

CSI-SH consisted of four sessions which included the following: (1) an overview of sexual health and an evaluation of the patient’s sexual health, (2) discussion of strategies to improve sexual functioning and overall well-being, (3) education on effective communication methods for the patient to use with their partner, and (4) providing additional resources such as educational booklets or relevant referrals. Both the mental health professional and the participant had CSI-SH manuals with corresponding session content.

From these discussions, the mental health professional worked with the participant to formulate and implement a customized treatment plan. The homework and follow-up calls were utilized to help the patient work through any issues. The intervention culminated with a review of techniques learned and progress made aimed at preventing future issues and continued strategies to improve sexual health.

Sessions were audio taped and rated for fidelity of session content. Of the 33 women enrolled in CSI-SH and included for analysis, 26 completed ≥1 session, and of these, 9 cases were assessed for fidelity. The average fidelity rating of the therapist to the CSI-SH manual was 96 % (range 63–100 %). Of the 26 participants who completed ≥1 session, 19 self-reported their degree of homework adherence and the average rating of adherence was 89 %.

Main outcome measures

Medical and sociodemographic information

As above, patients’ medical charts—including pathology and lab results, physician assessments and reports, and other health information—were used to assess eligibility and provide background information. In addition, participants self-reported demographic information.

Female Sexual Function Index (primary outcome) [28]

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) assessed sexual functioning across desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and pain/discomfort, sexual/relationship satisfaction subscales, and total score. Internal consistency reliability coefficients ranged from 0.76 to 0.96.

Impact of Events Scale-Revised (secondary outcome) [29]

The Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) assessed severity of cancer distress across domains of hyperarousal, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and total score. Internal consistency reliability coefficients for the three subscales ranged from 0.82 to 0.85 and 0.93 for the total score.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (secondary outcome) [30]

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) assessed psychological distress severity across depression and anxiety subscales. Respective internal consistency reliability coefficients were 0.87 and 0.77.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (secondary outcome) [31]

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) assessed health-related QoL across Global Quality of Life (QL) and Emotional Functioning (EF) subscales. Respective internal consistency reliability coefficients were 0.87 and 0.85.

Statistical analysis

Means were calculated for each of the psychometric outcome measures by assessment time (baseline, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2) and by treatment arm. Differences between arms for each assessment time were evaluated by two-sample t tests. The threshold for statistical significance for all statistical tests was p < 0.05, and p < 0.10 was used to indicate marginal significance.

Effect size estimates (i.e., standardized mean difference or Cohen’s d) were calculated for differences between the study arms to indicate change from baseline to follow-up 1 and baseline to follow-up 2. We used the convention of small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) Cohen’s d effect sizes [32]. We evaluated efficacy separately at the two follow-up times because we were interested in detecting the presence and magnitudes of any initial treatment effects (i.e., follow-up 1) and whether those effects were maintained over time (i.e., follow-up 2). This information was valuable for planning future studies and for suggesting potential improvements to the intervention.

After this study was designed, strong evidence emerged from our clinical observations and the empirical literature that indicated that the FSFI may not be a psychometrically valid measure of sexual functioning among women who are not sexually active [33]. Therefore, we also calculated these effect sizes excluding women who were not sexually active at baseline (see Table 2). Similar to prior studies [33, 34], women who left blank or indicated no sexual activity/ intercourse to ≥8 of the 15 FSFI questions with this response option were considered to have insufficient sexual activity for the FSFI to be a valid assessment of their functioning. This analysis of the subgroup of women considered sexually active at baseline was not a part of the original analysis plan in the protocol for this RCT; however, given that the validity of the FSFI as an outcome measure is contingent upon its use among sexually active respondents, we felt it important to present the effect sizes for this sexually active subgroup in order to provide the most appropriate effect size estimates for researchers planning similar studies that will utilize the FSFI.

Table 2.

Demographic and medical characteristics by treatment group

| Variable | Intervention (n = 33) | Usual care (n = 37) | All (N = 70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), or %a | Mean (SD), or %a | Mean (SD), or %a | |

| Sociodemographic/sexual health | |||

| Age (years) | 56.73 (12.57) | 54.27 (10.77) | 55.43 (11.64) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 72.7 | 78.4 | 75.7 |

| Education (% completed college or higher) | 62.0 | 66.7 | 64.5 |

| Marital Status (% married/partnered) | 57.6 | 56.8 | 57.1 |

| Children (% yes) | 78.8 | 83.8 | 81.4 |

| Employed (% full/part-time) | 50.0 | 47.2 | 48.5 |

| Income (% ≥USD 50,000/year) | 70.4 | 67.9 | 69.1 |

| Sexually active at baseline (% yes) | 66.7 | 51.4 | 58.6 |

| Prognostic/medical | |||

| Cancer type (% rectal) | 68.8 | 70.3 | 69.6 |

| Stage | |||

| Stage I (%) | 26.1 | 45.5 | 35.6 |

| Stage II (%) | 17.4 | 13.6 | 15.6 |

| Stage III (%) | 56.5 | 40.9 | 48.9 |

| Post-menopause (% yes) | 90.3 | 89.2 | 89.7 |

| Treatment | |||

| Surgery (% yes) | 74.2 | 75.7 | 75.0 |

| Permanent Stoma (% yes) | 15.2 | 13.5 | 14.3 |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO; % yes) | 19.4 | 24.3 | 22.1 |

| Radiation therapy (% yes) | 80.6 | 70.3 | 75.0 |

| Chemotherapy (% yes) | 90.3 | 81.1 | 85.3 |

| Years since any treatment | 5.18 (4.28)* | 3.43 (1.94)* | 4.26 (3.35) |

| ≥5 years since any treatment (% yes) | 37.5* | 13.5* | 24.6 |

Two-sample t test (continous variables) or Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables) significant, p < 0.05

Percentages calculated using only valid, non-missing values

Linear regression models assessed the effect of the treatment arm (CSI-SH vs. AO) on outcomes at follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 after adjusting for a number of covariates. Specifically, each model controlled for the baseline score on the given scale, age, marital status (married/partnered vs. other status), menopausal status (menopausal vs. not), and years since treatment. We chose these a priori due to their likely associations with outcome variables. Baseline scores, age, and years since treatment were mean-centered. For the FSFI total score only, an additional model was fit that excluded women not sexually active at baseline. We fit this additional model in this subgroup of 41 women sexually active at baseline because of the strong evidence that the FSFI is not a psychometrically valid measure of sexual functioning among women who are not sexually active. Although the sample size for this subgroup model was smaller than the corresponding model that included the full sample, we expected the FSFI to be more sensitive to potential differences between the treatment arms due to its superior psychometric properties among this subgroup.

Results

Nine patients dropped out of the study before completing follow-up 1. Significantly more patients were from the CSI-SH arm compared with the AO arm (eight vs. one patient; p = 0.010). Fifteen of the 70 patients (12 CSI-SH and 3 AO, p = 0.007) completing the baseline assessment did not complete the trial. There were no other associations between attrition and the baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics (Table 2).

Overall, participants were middle-aged (M = 55.43) well-educated (64.5 % college graduate or higher), married (57.1 %), and non-Hispanic White (75.7 %) women with children (81.4 %). Most (89.7 %) were menopausal. In general, study arms were equivalent on baseline sociodemographic and disease/treatment characteristics (Table 2). One exception was that significantly more time had passed since treatment initiation among CSI-SH patients compared with AO patients (M = 5.18 vs. M = 3.43 years, respectively; p = 0.028).

Baseline FSFI sexual functioning scores and measures of psychological distress (BSI, QLQ-C30 EF subscale, IES cancer-specific distress) did not significantly differ between the study arms (Table 3). In general, all scores tended to improve at follow-up 1 compared to baseline (Table 3) but remained similar between the arms at follow-ups 1 (two-sample t test) and 2.

Table 3.

Mean scores at each assessment time by treatment arm and significant treatment arm differences in score changes from baseline to follow-up 1 and follow-up 2

| Variable | Baseline

|

Follow-up 1

|

Follow-up 2

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 33) | Usual care (n = 37) | t test | Intervention (n = 25) | Usual care (n = 35) | t test | Intervention (n = 21) | Usual care (n = 32/33) | t test | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| FSFI | |||||||||

| Desire | 2.53 (0.97) | 2.68 (1.22) | 0.573 | 2.81 (0.96) | 2.71 (1.16) | 0.718 | 2.60 (1.06) | 2.73 (1.11) | 0.676 |

| Arousal | 2.20 (1.85) | 2.08 (2.10) | 0.806 | 3.42 (1.99) | 2.67 (2.11) | 0.164 | 2.74 (2.24) | 2.40 (2.11) | 0.578 |

| Lubrication | 2.14 (2.10) | 2.16 (2.40) | 0.968 | 3.10 (2.27) | 2.54 (2.30) | 0.354 | 2.89 (2.51) | 2.27 (2.26) | 0.369 |

| Orgasm | 2.61 (2.11) | 2.28 (2.40) | 0.548 | 3.79 (2.26) | 2.64 (2.30) | 0.058a | 2.99 (2.60) | 2.61 (2.38) | 0.593 |

| Satisfaction | 2.82 (1.52) | 3.10 (1.86) | 0.484 | 3.75 (2.07) | 3.52 (1.80) | 0.654 | 3.21 (2.08) | 3.35 (1.58) | 0.794 |

| Pain | 2.12 (2.29) | 1.91 (2.48) | 0.717 | 2.74 (2.45) | 2.17 (2.40) | 0.379 | 2.61 (2.41) | 1.88 (2.58) | 0.297 |

| Total | 14.41 (9.15) | 14.20 (10.95) | 0.931 | 19.60 (9.82) | 16.24 (10.69) | 0.213 | 17.04 (11.76) | 15.05 (10.03) | 0.528 |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | |||||||||

| QL | 76.77 (14.84) | 75.90 (20.30) | 0.838 | 81.67 (18.79) | 77.38 (21.06) | 0.411 | 80.16 (17.57) | 79.04 (15.88) | 0.814 |

| EF | 72.73 (21.88) | 77.93 (21.17) | 0.317 | 77.00 (20.02) | 75.95 (17.71) | 0.835 | 82.94 (17.97) | 75.76 (17.48) | 0.155 |

| IES-R | |||||||||

| Avoidance | 9.00 (8.81) | 5.84 (5.02) | 0.075 a | 7.90 (7.13) | 6.56 (5.17) | 0.426 | 7.57 (7.76) | 5.92 (5.17) | 0.396 |

| Interference | 9.39 (6.77) | 7.78 (5.12) | 0.271 | 6.40 (5.64) | 7.66 (5.08) | 0.38 | 6.81 (6.51) | 6.12 (5.46) | 0.689 |

| Hyperarousal | 4.79 (5.87) | 3.41 (4.02) | 0.261 | 3.16 (3.84) | 4.09 (4.51) | 0.396 | 2.86 (3.72) | 2.58 (3.20) | 0.777 |

| Total | 23.18 (19.34) | 17.03 (12.62) | 0.125 | 17.46 (14.42) | 18.30 (13.49) | 0.82 | 17.24 (16.23) | 14.62 (12.24) | 0.531 |

| BSI | |||||||||

| Depression | 0.71 (0.81) | 0.49 (0.56) | 0.195 | 0.56 (0.72) | 0.50 (0.59) | 0.754 | 0.53 (0.67) | 0.47 (0.51) | 0.702 |

| Anxiety | 0.74 (0.70) | 0.56 (0.50) | 0.24 | 0.59 (0.70) | 0.58 (0.45) | 0.922 | 0.44 (0.40) | 0.61 (0.67) | 0.248 |

FSFI Female Sexual Function Index, EORTC-QLQ-C30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire, OL EORTC QLQ-C30 General Quality of Life Subscale, EF EORTC QLQ-C30 Emotional Functioning Subscale, IES-R Impact of Events Scale-Revised, BSI Brief Symptom Inventory

Two-sample t test approaching significance, p < 0.10

Among all CSI-SH participants, effect sizes for the intervention at follow-up 1 were in the medium range but were smaller by follow-up 2. Notable exceptions were QLQ-C30 EF and FSFI lubrication, which actually had larger effect sizes at follow-up 2 (see Table 4). Among the 41 participants who were sexually active at baseline, follow-up 1 effect sizes were considerably larger than those estimated for all participants—in the medium to large ranges (see Table 4), with more maintenance of gains at follow-up 2.

Table 4.

Effect sizes for treatment arm differences in score changes from baseline to follow-up 1 and baseline to follow-up 2 with comparisons across all participants and comparisons across sexually active participants only

| Baseline to follow-up 1a

|

Baseline to follow-up 2a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score changes for all | Score changes for sexually active only | Score changes for all | Score changes for sexually active only | d direction indicating greater improvement in intervention arm | |

| Variable | d | d | d | d | |

| FSFI | |||||

| Desire | 0.31 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.54 | + |

| Arousal | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.18 | 0.47 | + |

| Lubrication | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.82 | + |

| Orgasm | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.28 | + |

| Satisfaction | 0.47 | 1.30 | 0.22 | 0.58 | + |

| Pain | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.90 | + |

| Total | 0.51 | 1.13 | 0.32 | 0.82 | + |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | |||||

| QL | 0.34 | 0.18 | −0.08 | 0.12 | + |

| EF | 0.67 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 0.93 | + |

| IES-R | |||||

| Avoidance | −0.43 | −1.15 | −0.46 | −1.13 | − |

| Interference | −0.57 | −0.48 | −0.26 | −0.48 | − |

| Hyperarousal | −0.62 | −0.66 | −0.24 | −0.80 | − |

| Total | −0.72 | −0.93 | −0.40 | −0.92 | − |

| BSI | |||||

| Depression | −0.40 | −0.29 | −0.26 | −0.35 | – |

| Anxiety | −0.41 | 0.00 | −0.53 | −0.59 | − |

FSFI Female Sexual Function Index, EORTC QLQ-C30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire, QL EORTC QLQ-C30 General Quality of Life Subscale, EF EORTC QLQ-C30 Emotional Functioning Subscale, IES-R Impact of Events Scale-Revised, BSI Brief Symptom Inventory

Small, medium, and large effect sizes correspond with d values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively.[32]

After controlling for baseline scores and other potentially relevant variables using linear regression (see Table 5), there were significant treatment effects at follow-up 1, with CSI-SH patients reporting significantly lower IES total cancer-specific stress and better QLQ-C30 EF (both p < 0.05). A nonsignificant trend to better FSFI total in the CSI-SH group was also observed (p < 0.10). At follow-up 2, only the QLQ-C30 EF treatment effect remained significant. At follow-up 2, married patients reported significantly more IES total cancer-specific distress than other patients (p = 0.016). Among women sexually active at baseline, there were significant treatment effects (p < 0.05) at both follow-ups, with CSI-SH participants scoring over 6.5 points higher on average on the FSFI total than the AO participants (Table 5).

Table 5.

Linear regression model estimates for follow-up 1 and follow-up 2 FSFI total, EORTC-QLQ-C30 EF, and IES-R total scores

| Variable | Follow-up 1 score regressions

|

Follow-up 2 score regressions

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | t value | Pr (>|t|) | Estimate | Standard error | t value | Pr (>|t|) | |

| FSFI total | ||||||||

| Intercept | 19.732 | 3.473 | 5.682 | 0.0001 | 14.586 | 3.9 | 3.74 | 0.0001 |

| Baseline scorea | 0.634 | 0.094 | 6.751 | 0.0001* | 0.76 | 0.103 | 7.357 | 0.0001* |

| Age (years)a | −0.01 | 0.091 | −0.107 | 0.915 | −0.103 | 0.097 | −1.067 | 0.292 |

| Married | 2.38 | 1.929 | 1.234 | 0.223 | −1.406 | 2.12 | −0.663 | 0.511 |

| Post-menopausal | −5.337 | 3.42 | −1.561 | 0.125 | 1.279 | 3.873 | 0.33 | 0.743 |

| Years since treatmenta | 0.427 | 0.298 | 1.434 | 0.157 | −0.064 | 0.377 | −0.17 | 0.866 |

| In intervention arm | 3.349 | 1.991 | 1.683 | 0.098** | 3.03 | 2.188 | 1.385 | 0.173 |

| FSFI total (among sexually active women only) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 17.99 | 5.131 | 3.506 | 0.002 | 14.543 | 5.802 | 2.507 | 0.02 |

| Baseline scorea | 0.721 | 0.188 | 3.823 | 0.001* | 0.733 | 0.21 | 3.488 | 0.002* |

| Age (years)a | −0.059 | 0.108 | −0.544 | 0.591 | −0.155 | 0.117 | −1.329 | 0.197 |

| Married | −0.505 | 2.365 | −0.213 | 0.833 | −4.391 | 2.713 | −1.618 | 0.119 |

| Post-menopausal | −3.407 | 3.966 | −0.859 | 0.398 | 2.249 | 4.706 | 0.478 | 0.637 |

| Years since treatmenta | −0.014 | 0.321 | −0.044 | 0.965 | −0.547 | 0.47 | −1.165 | 0.256 |

| In intervention arm | 6.648 | 2.721 | 2.443 | 0.021* | 6.511 | 3.003 | 2.169 | 0.041* |

| IES-R total | ||||||||

| Intercept | 18.89 | 4.135 | 4.569 | 0.0001 | 15.098 | 5.093 | 2.964 | 0.0001 |

| Baseline scorea | 0.74 | 0.073 | 10.096 | 0.0001* | 0.659 | 0.092 | 7.147 | 0.0001* |

| Age (years)a | 0.109 | 0.107 | 1.018 | 0.313 | −0.068 | 0.126 | −0.539 | 0.592 |

| Married | 1.757 | 2.252 | 0.78 | 0.439 | 6.983 | 2.787 | 2.506 | 0.016* |

| Post-menopausal | 0.954 | 4.042 | 0.236 | 0.814 | −2.919 | 5.039 | −0.579 | 0.565 |

| Years since treatmenta | 0.208 | 0.35 | 0.594 | 0.555 | −0.89 | 0.485 | −1.837 | 0.073** |

| In intervention arm | −5.723 | 2.359 | −2.426 | 0.019* | −0.461 | 2.878 | −0.16 | 0.873 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 EF | ||||||||

| Intercept | 75.427 | 5.833 | 12.932 | 0.0001 | 81.139 | 7.24 | 11.207 | 0.0001 |

| Baseline scorea | 0.713 | 0.076 | 9.357 | 0.0001* | 0.532 | 0.091 | 5.822 | 0.0001* |

| Age (years)a | −0.14 | 0.158 | −0.884 | 0.381 | −0.02 | 0.184 | −0.111 | 0.912 |

| Married | −1.827 | 3.147 | −0.58 | 0.564 | −5.677 | 3.82 | −1.486 | 0.144 |

| Post-menopausal | −0.214 | 5.709 | −0.038 | 0.97 | −2.849 | 7.177 | −0.397 | 0.693 |

| Years since treatmenta | −0.254 | 0.497 | −0.512 | 0.611 | 0.825 | 0.689 | 1.198 | 0.237 |

| In intervention arm | 7.116 | 3.391 | 2.099 | 0.041* | 8.852 | 4.098 | 2.16 | 0.036* |

FSFI Female Sexual Function Index, EF EORTC QLQ-C30 Emotional Functioning Subscale, IES-R Impact of Events Scale-Revised, BSI Brief Symptom Inventory.

Linear regression coefficient significant, p < 0.05;

linear regression coefficient marginally significant, p < 0.10

Baseline scores, age, and years since treatment were centered around their respective means before entry into the models

Discussion

We reported the preliminary efficacy of a sexual health education intervention RCT for female rectal/anal cancer survivors in this pilot study designed to provide effect size estimates for a larger subsequent study. Although differences supporting our primary hypothesis that the CSI-SH intervention would ultimately lead to higher levels of sexual functioning did not achieve significance, results suggest that the intervention may improve a number of dimensions of QoL, particularly for women who were sexually active at baseline. These results provide important preliminary data to inform the development of a larger intervention trial targeting sexual dysfunction and reduced QoL in survivors of rectal and anal cancer that are rarely treated. However, the data also suggest that additional strategies are needed to promote the impact of the intervention over time. For example, strategies to increase motivation and the inclusion of the women’s partners may increase the impact and duration of the intervention.

The two groups were largely equivalent on baseline characteristics, although slightly more time had passed since treatment initiation among CSI-SH patients. Both groups of women showed improvements by follow-up 1. However, after adjusting for baseline scores and other potential confounders, CSI-SH patients reported significantly better overall sexual functioning—as well as lower psychological distress (cancer-specific distress; EF QoL). The significant difference in EF QoL was maintained at follow-up 2. For the majority of outcomes, effect size estimates showed the intervention to have the largest effects earlier on (i.e., from baseline to follow-up 1).

The intervention was more efficacious for sexually active women at follow-up 1 with better maintenance and even a few additional gains at follow-up 2. Particularly large effect sizes were noted for lubrication, sexual pain, and psychosocial distress (EF QoL, avoidance, total cancer-specific distress).

Limitations

The results of the current study are novel and encouraging; however, they must be considered in light of study limitations. This was a pilot study and therefore presents results of a relatively small sample of survivors. Indeed, the sample was smaller than was initially proposed based on our power analysis. Further, the inclusion criteria were limited to women who reported low to moderate degrees of satisfaction with their sexual functioning, and thus, caution must be used in generalizing these results to the broader survivor population. It is important to note that despite this targeted inclusion of women with low or moderate satisfaction, recruitment to this trial was challenging. This may speak to the challenge of conducting research on a sensitive topic that is not regularly discussed by health care providers in the context of cancer treatment and survivorship [35]. Additionally, we only focused on the patient and did not include partners.

In addition, our sample was rather heterogeneous in regard to time that had elapsed since treatment, ranging from 2 to 20 years post-treatment, and despite randomization, a difference emerged between the treatment and control group. Although it is important to note that women who were, on average, 5 years from treatment still reported high rates of sexual dysfunction, it remains to be seen whether such an intervention would be more effective if offered closer to time of treatment. Further, the CSH-CH intervention was delivered by clinicians with specialized training in psycho-oncology, and thus, further research is required to assess whether this intervention could be effective if delivered in routine clinical populations by other health professionals. Lastly, the assessment criteria for sexual dysfunction using the psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) were not used as part of this pilot study (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) [36].

Future directions

The limitations noted provide fertile ground for future research in this important and understudied domain of cancer survivorship. Sexual health is important for both partnered and un-partnered women, and thus, the current trial was open to both groups. However, future investigations should more fully consider the potential role of an existing partner and their relationship dynamics, if applicable, given the interwoven nature of sexual functioning and relationship satisfaction. Additional important relationship components and their measurement may increase the impact and the detection of the effect of an intervention, such as a focus on intimacy in cancer survivorship [37]. Although it would be important to know if the treatment that the women received was their first treatment for this disease, this information was not collected in this study and would be important to address in future research. Finally, the current study utilized a phone-based approach to health education to increase reach and retention of participants and provide an alternative to a face-to-face intervention. A recent study by Schover and colleagues has found promising results for an internet-based sexual health intervention with breast and gynecological cancer survivors [38]. Future research in this domain should consider ways to further leverage existing technology to improve care and increase the potential for dissemination beyond specialty clinics. For example, online resources, interactive internet modules, Skype, and instructional DVD’s could be utilized to enhance the existing intervention. Lastly, in future research, assessment of sexual dysfunction, using current DSM criteria, would add to the description of the sample.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA129195 and T32 CA009461) and the MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, Eckel R, Sauer H, Holzel D. Quality of life in rectal cancer patients: a four-year prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):203–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000080823.38569.b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter J, Goldfrank D, Schover LR. Simple strategies for vaginal health promotion in cancer survivors. J Sex Med. 2011;8(2):549–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gervaz P, Bucher P, Konrad B, Morel P, Beyeler S, Lataillade L, et al. A Prospective longitudinal evaluation of quality of life after abdominoperineal resection. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97(1):14–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panjari M, Bell RJ, Burney S, Bell S, McMurrick PJ, Davis SR. Sexual function, incontinence, and wellbeing in women after rectal cancer—a review of the evidence. J Sex Med. 2012;9(11):2749–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, Asano T, Cohen Z, Swallow CJ, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242(2):212–23. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li CC, Rew L. A feminist perspective on sexuality and body image in females with colorectal cancer: an integrative review. J wound Ostomy Continence Nurs: Off Publ Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs Soc / WOCN. 2010;37(5):519–25. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181edac2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho VP, Lee Y, Stein SL, Temple LK. Sexual function after treatment for rectal cancer: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(1):113–25. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fb7b82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts and figures, 2011–2013. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welzel G, Hagele V, Wenz F, Mai SK. Quality of life outcomes in patients with anal cancer after combined radiochemotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol: Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft. 2011;187(3):175–82. doi: 10.1007/s00066-010-2175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aerts L, Enzlin P, Vergote I, Verhaeghe J, Poppe W, Amant F. Sexual, psychological, and relational functioning in women after surgical treatment for vulvar malignancy: a literature review. J Sex Med. 2012;9(2):361–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahnen DJ, Wade SW, Jones WF, Sifri R, Mendoza Silveiras J, Greenamyer J, et al., editors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2014. The Increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: a call to action. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmack Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn EH, Bodurka DC. Predictors of sexual functioning in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):881–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.08.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greendale GA, Petersen L, Zibecchi L, Ganz PA. Factors related to sexual function in postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer. Menopause (New York, NY) 2001;8(2):111–9. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, Sharpe L, McLeod C, Hacker N. Post-treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: a qualitative insight. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(3):267–79. doi: 10.1002/pon.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, Blacker C, Kresge CL, Decker VB, et al. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2005;11(6):440–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Patient-rating of distressful symptoms after treatment for early cervical cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81(5):443–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corney RH, Everett H, Howells A, Crowther ME. Psychosocial adjustment following major gynaecological surgery for carcinoma of the cervix and vulva. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36(6):561–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onujiogu N, Johnson T, Seo S, Mijal K, Rash J, Seaborne L, et al. Survivors of endometrial cancer: who is at risk for sexual dysfunction? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123(2):356–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21(6):594–601. doi: 10.1002/pon.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. Cancer J (Sudbury, Mass) 2009;15(1):74–7. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3712–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brotto LA, Erskine Y, Carey M, Ehlen T, Finlayson S, Heywood M, et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(2):320–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefford M, Lotfi-Jam K, Baravelli C, Grogan S, Rogers M, Krishnasamy M, et al. Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34(3):E1–10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f22f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Cancer Society. Sexuality for the woman with cancer. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118(2):500–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, Labay LE, Rini C, Meschian YM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3754–61. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.26.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller KE, Barton CN. Approximate power for repeated-measures ANOVA lacking sphericity. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(406):549–55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen CB, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derogatis LR, Spencer P. Brief Symptom Inventory: BSI. Pearson; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4606–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philip EJ, Nelson C, Temple L, Carter J, Schover L, Jennings S, et al. Psychological correlates of sexual dysfunction in female rectal and anal cancer survivors: analysis of baseline intervention data. J Sex Med. 2013;10(10):2539–48. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jennings S, Philip EJ, Nelson C, Schuler T, Starr T, Jandorf L, et al. Barriers to recruitment in psycho-oncology: unique challenges in conducting research focusing on sexual health in female survivor-ship. Psycho-Oncology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pon.3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5. Arlington, VA: 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoole SP, Jaworski C, Brown AJ, McCormick LM, Agrawal B, Clarke SC, et al. Serial assessment of the index of microcirculatory resistance during primary percutaneous coronary intervention comparing manual aspiration catheter thrombectomy with balloon angioplasty (IMPACT study): a randomised controlled pilot study. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000238. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schover LR, Yuan Y, Fellman BM, Odensky E, Lewis PE, Martinetti P. Efficacy trial of an Internet-based intervention for cancer-related female sexual dysfunction. J Natl Compr Canc Netw: JNCCN. 2013;11(11):1389–97. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]