Abstract

We found that stretching type I rat alveolar epithelial cell (RAEC) monolayers at magnitudes that correspond to high tidal-volume mechanical ventilation results in the production of reactive oxygen species, including nitric oxide and superoxide. Scavenging superoxide with Tiron eliminated the stretch-induced increase in cell monolayer permeability, and similar results were reported for rats ventilated at large tidal volumes, suggesting that oxidative stress plays an important role in barrier impairment in ventilator-induced lung injury associated with large stretch and tidal volumes. In this communication we show that mechanisms that involve oxidative injury are also present in a novel precision cut lung slices (PCLS) model under identical mechanical loads. PCLSs from healthy rats were stretched cyclically to 37 % change in surface area for 1 hour. Superoxide was visualized using MitoSOX. To evaluate functional relationships, in separate stretch studies superoxide was scavenged using Tiron or mito-Tempo. PCLS and RAEC permeability was assessed as tight junction (TJ) protein (occludin, claudin-4 and claudin-7) dissociation from zona occludins-1 (ZO-1) via co-immunoprecipitation and Western blot, after 1 hour (PCLS) or 10 minutes (RAEC) of stretch. Superoxide was increased significantly in PCLS, and Tiron and mito-Tempo dramatically attenuated the response, preventing claudin-4 and claudin-7 dissociation from ZO-1. Using a novel PCLS model for ventilator-induced lung injury studies, we have shown that uniform, biaxial, cyclic stretch generates ROS in the slices, and that superoxide scavenging that can protect the lung tissue under stretch conditions. We conclude that PCLS offer a valuable platform for investigating antioxidant treatments to prevent ventilation-induced lung injury.

Keywords: lung injury, tight junctions, permeability, oxidative stress

Introduction

Mechanical ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) occurs in 5% to 15% of all patients who require mechanical ventilation, or 200,000 annually in the US (Parker, Hernandez et al. 1993, Ware and Matthay 2000, Johnson and Matthay 2010), with a mortality rate of 34-60% in ventilated patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Haake, Schlichtig et al. 1987). VILI is characterized by acute respiratory failure, alveolar cell dysfunction, and profound changes in barrier permeability (Wirtz and Dobbs 1990, Parker, Hernandez et al. 1993, Lecuona, Saldias et al. 1999, Waters, Ridge et al. 1999, Dos Santos and Slutsky 2000, Slutsky and Ranieri 2000, Ware and Matthay 2000, Ricard, Dreyfuss et al. 2003). Human and animal studies have demonstrated that VILI is associated with mechanical ventilation with high regional lung volumes (Egan 1982, Kim and Crandall 1982, Tsuno, Miura et al. 1991, Dreyfuss and Saumon 1998), and may also be related to reopening of collapsed lung regions (Muscedere, Mullen et al. 1994, Matthay, Bhattacharya et al. 2002). Consequently, the biomechanical environmental determinants of lung injury (inspired tidal volume, frequency, and use of positive end-expiratory pressure to ensure more uniform lung expansion) are central to designing injury mitigation strategies. ARDS results in diffuse pulmonary endothelial and epithelial damage, neutrophil accumulation, transudation of proteins into the interstitial and alveolar spaces and a loss of type I pneumocytes (Ware and Matthay 2000). Current management recommendations to limit acute lung injury in patients with ARDS include use of low tidal volumes (Brower, Matthay et al. 2000, Brower and Rubenfeld 2003) and fluid conservative protocols (Johnson and Matthay 2010). There is a paucity of options available for reducing the morbidity and mortality during ventilation when small tidal volumes fail to achieve sufficient gas exchange. Consequently, in this communication we focus on mechanisms associated with altered lung barrier properties during moderate tidal volumes and stretch, to identify opportunities to intervene and ameliorate lung injury.

The alveolar epithelium provides nearly all of the barrier properties to protein passage and over 90% of the resistance to the transport of nonpolar and charged solutes (Lubman, Kim et al. 1997), such that extra-alveolar fluid is excluded from the alveoli by the active and passive barrier properties of the alveolar epithelial lining (Bai, Fukuda et al. 1999, Ma, Fukuda et al. 2000, Borok and Verkman 2002), even in the presence of impaired endothelial barrier properties and interstitial edema. The tight junctions (TJ) located between adjacent Type I epithelial cells are the primary barrier to paracellular transport (Mitic and Anderson 1998). Occludin (Chen, Merzdorf et al. 1997, Saitou, Ando-Akatsuka et al. 1997) and claudins (4, 5, 7 and 18) are the principal TJ proteins regulating paracellular barrier resistance and charge selectivity in the Type I lung epithelium, as well as zonula occludens (ZO-1, located between TJ proteins and cytoskeletal proteins) (Stevenson, Anderson et al. 1989, Tsukamoto and Nigam 1997, Denker and Nigam 1998, Sandoval, Zhou et al. 2002, Wang, Daugherty et al. 2003). TJ permeability is correlated with actin reorganization (Bacallao, Garfinkel et al. 1994, Fanning 2001), actin-bound pools of TJ proteins (Basuroy, Seth et al. 2006), and quantities of TJ proteins (Tsukamoto and Nigam 1997, Balda and Matter 2000, Fanning 2001). Previously we reported stretch-magnitude dependent changes in TJ proteins, actin arrangement and barrier dysfunction in pulmonary epithelial monolayers (Cavanaugh, Oswari et al. 2001, Cavanaugh, Cohen et al. 2006, Cohen, Cavanaugh et al. 2008, Cohen, Gray Lawrence et al. 2010, DiPaolo, Lenormand et al. 2010, Cohen, DiPaolo et al. 2012, Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013, Dipaolo, Davidovich et al. 2013). We hypothesize that reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediate TJ rearrangement and barrier dysfunction during stretch.

Exposure of unstretched cells and tissues to ROS has been shown to increase permeability (Shasby, Vanbenthuysen et al. 1982, Chapman, Waters et al. 2002, Tasaka, Amaya et al. 2008). In the lung, oxidative stress studies in unstretched cells are primarily performed with either cell lines or Type II alveolar epithelial cells. Recently we demonstrated the cyclic stretch of primary epithelial cells with Type I properties increased monolayer permeability, mediated via stretch-associated superoxide release (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). Although we have reported cell morbidity and mortality during “sighs” and sustained cyclic stretch of isolated primary Type I-like alveolar epithelial cells are comparable to intact in vivo lungs (Mitra, Sammani et al. , Tschumperlin and Margulies 1998, Fisher and Margulies 2002), when we co-cultured Type I and Type II RAECs, we reported interactions between resident cells, such that stretch-induced surfactant release was mediated by paracrine ATP signaling between Type I and Type II cells (Patel, Reigada et al. 2005). This evidence suggests that our established monoculture preparation may not capture all elements of the intact lung milieu with its spectrum of cell types. In this communication, we determine if our previous results in monolayers relating stretch-induced ROS mediated increases in permeability are relevant to the intact lung using a novel preparation, cyclically stretched lung slices (Davidovich, Chhour et al. 2013, Davidovich, Huang et al. 2013), and we hypothesize that like alveolar epithelial monolayers, stretch induces ROS release, which in turn potentiates tight junction protein dissociation.

Methods

All protocols for isolating rat alveolar epithelial cells (RAECs) and rat precision cut lung slices (PCLSs) were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee. Permeability of RAEC monolayers was evaluated with and without cyclic stretch to 37 percent change in surface area (%SA) for 10 minutes, and with and without superoxide scavenger Tiron or MitoTempo. At least 2 monolayers from every rat were evaluated for each experimental group, at least 3 rats per group. All remaining studies for ROS release and TJ protein association were performed in unstretched or stretched (37%ΔSA for 1 hour) PCLSs, and with and without superoxide scavenger Tiron or MitoTempo. We used 2 or 3 slices per rat, and at least 6 rats per group. For each study, the number of rats or PCLSs per group (n) are provided.

Rat Alveolar Epithelial Cell (RAEC) Monolayer Permeability with Stretch

Previously, we used permeable deformable substrates to measure permeability across RAEC monolayers, and observed that large deformations within the physiological range increased tracer transport (0.15-0.55 nm) dramatically (Cavanaugh, Cohen et al. 2006). Using the data from a spectrum of tracers we modeled the monolayer as theoretical population of large and small radii. Unstretched monolayers were nearly entirely (99.9986%) composed of small pores (0.4 nm), with the remainder large pores (4.3 nm) occupying only 0.15% of the total transport area. After cyclic stretch to 37% ΔSA for 1 hour, permeability to tracers of all sizes increased significantly, and both the small and large theoretical pore radii increased (0.9 and 6.3 nm, respectively), and the number of large pores increased 10-fold, and number of small pores decreased (Cavanaugh, Cohen et al. 2006). To measure transport in cells cultured on impermeable silastic membranes we developed several novel methods (Cavanaugh and Margulies 2002, Song, Davis et al. 2015), and recently showed that our method whereby trans-monolayer transport of FITC-streptavidin (60kD, likely through the expanded large pores) to bind at the biotinylated fibronectin-coated silastic membrane was more sensitive for measuring RAEC monolayer permeability than our previously published method utilizing BODIPY-ouabain binding to basolateral cell surfaces (Song, Davis et al. 2015). Because interpretation of the BODIPY-ouabain method developed in our laboratory (Cavanaugh and Margulies 2002) is complicated by reporter binding (as well as permeability) that is sensitive to stretch (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013), in this communication, we also sought to confirm our previous report in which we found ROS mediated stretch-induced permeability increases in RAEC permeability (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). To confirm those previous findings using our superior method, we isolated Type II RAECs from Sprague Dawley rats (250g~350g, n=3~5) as previously described (Tschumperlin and Margulies 1998, Tschumperlin, Oswari et al. 2000), and cultured on plasma-treated biotinylated fibronectin-coated silastic membranes (3 wells per rat, per group) as reported previously (Song, Davis et al. 2015) for 4 days, until they expressed Type I-specific TJ proteins and barrier properties (Cavanaugh, Oswari et al. 2001, Oswari, Matthay et al. 2001, Cavanaugh, Cohen et al. 2006). Using our improved method to measure permeability, on the day of study, RAEC monolayers were designated as vehicle controls or treated with superoxide scavengers prior to stretch for 2hr after 1hr serum deprivation in DMEM+HEPES: 500μM of mitoTempo (n=5, Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, USA) or 10mM of Tiron (n=3) in DMEM+HEPES. The concentration of mitoTempo was derived from the literature (Nakahira, Haspel et al. 2011, Iyer, He et al. 2013), and the concentration of Tiron was used by us previously and shown to completely reduce superoxide to unstretched levels (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). Vehicle control (VC; n=5) wells were provided 1μl of DMSO in DMEM+HEPES. Using our custom-designed multi-well device which imparts equi-biaxial uniform stretch to cells seeded on flexible membranes, cyclic stretch of 37% ΔSA (17% engineering strain in radial and azimuthal directions) was applied to RAEC monolayers for 10 min at a rate of 0.25Hz, equivalent to inflation to total lung capacity at a human-like respiratory rate (Tschumperlin and Margulies 1998, Cohen, Gray Lawrence et al. 2010). Previously, we reported changes in permeability at this stretch magnitude after only 10 minutes, and that these barrier disruptions were significantly mitigated with superoxide scavenger Tiron (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). During cyclic stretch, FITC-streptavidin (25 μg/ml in DMEM+HEPES; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) was added, which bound to any exposed biotinylated fibronectin via intercellular breaches in the TJs. After stretch, each monolayer was washed with DMEM+HEPES three times, and three fluorescent fields were captured with a Nikon TE-300 inverted epifluorescence microcope. Monolayer permeability was evaluated from the proportion of the field that was above a FITC-positive threshold obtained from unstretched VC wells via a custom image analysis program, described elsewhere (Song, Davis et al. 2015). Image acquisition settings remained constant for data from each rat. Data from the 3 image fields were averaged.

Precision-Cut- Lung Slices (PCLSs) and Mechanical Stretch

Isolated lungs from Sprague Dawley rats (n=4~12) were inflated with a low-melting point agarose, and 250μm thick slices which contained no major airways or blood vessels were cut using VT 1000S tissue slicer (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, USA), incubated floating in serum-free minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 0.5 μl/ml gentamicin and 1 μl/ml amphotericin B and kept in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for at least 24 hours prior to stretch. To remove residual agarose and cellular debris, the medium was changed every 30 min for first 2 h, every 1 h for the next 2 h, and every 24 h thereafter. Immediately before stretching, slices were stitched using a 5-0 non-absorbable silk suture in a star-shaped pattern onto a silastic membrane mounted in custom wells (Davidovich, Huang et al. 2013). PCLSs were stretched in the same device as the RAECs in a uniform biaxial manner to 37% ΔSA for 1hr at a frequency of 0.25Hz. As with RAECs, prior to stretch, each PCLS was designated as a vehicle control (VC), or treated with superoxide scavenger mitoTempo or Tiron for 2hr after serum deprivation. Medium was collected for ROS release, PCLSs were used to image ROS or TJ proteins, or were homogenized for Western blots or immunoprecipitation (IP), all described below.

Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in PCLS

We measured nitric oxide (NO) from collected culture medium obtained from stretched and unstretched PCLSs, using the Griess reaction assay for nitrite ion NO2- (Salzman, Menconi et al. 1995, Mohammed, Nasreen et al. 2007). We evaluated mitochondrial ROS levels in living cells of the PCLS exposed to cyclic stretch using intracellular fluorogenic indicators for a broad spectrum of ROS (CellROX™) and for superoxide (MitoSOX™) (5μM in DMEM+HEPES; Life Technologes, Grand Island, USA)(Hansen-Hagge, Baumeister et al. 2008, Han, Varadharaj et al. 2009, Lee, Ryter et al. 2011). All tracers were added after the completion of stretch. MitoSox and CellRox image intensity associated with the parenchyma was determined in a multi-step MatLab routine, utilizing Otsu's method for defining optimal thresholds to create binary images from grayscale images (Otsu 1979). First, to determine the numerator of this outcome metric, or the total area of MitoSox- or CellRox-positive pixels in the image field, the average intensity in the unstretched PCLS images was obtained from each rat, and the lowest average intensity was used to threshold the stretched images from all rats, and all pixels in the field about the threshold were determined. Second, to identify denominator, or the number of pixels associated with parenchyma, we identified a median Otsu threshold from all unstretched grayscale images (both MitoSOX and CelROX images) for every rat, and used the median value as a filter across all rats to triage pixels into parenchyma (light) or airspace (dark). To determine the total parenchymal area in the image, we subtracted the total number of pixels associated with airspaces from the total image area in every image. Finally we divided the MitoSox- or CellRox-positive area by the area of parenchyma in each field, to determine the fraction tissue positive for Mitosox or Cellrox in each image. Values from the 3 fields obtained from each rat for every condition were averaged.

TJ Protein Dissociation

After 1 hr of cyclic stretch to 37%ΔSA or in unstretched PCLS, PCLSs (n=4 per group) were washed with cold DPBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+, and IP-lysis buffer with EDTA and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, USA) was added to the PCLS, and slices were combined to create one lysate per rat, per group. We performed a co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) with ZO-1 as a bait protein using an IP-kit (Thermo scientific, Waltham, USA), using 200μg of lysate and 5 μg of ZO-1 antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). After co-IP, Occludin, Claudin-4, Claudin-7, and ZO-1 were probed by immunoblot, and quantified by densitometry. The band intensity of Occludin, Claudin-4, and Claudin-7 were normalized to that of ZO-1, to compare the quantity of TJ protein bound to ZO-1 across groups. Finally, results from each stretched sample (str-VC and str-mitoTempo) were normalized to values from unstretched lysate (uns-VC) from the same rat. To identify if detectable increases in permeabililty are associated with TJ protein dissociation, we performed the same TJ dissociation analyses on unstretched and cyclically stretched (10 min, 37% ΔSA) untreated RAEC monolayers (n=4 per group), and compared results with measures of permeability, as described above.

Statistical analysis

For permeability, Mitosox, and Cellrox measurements, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis was performed for statistical significance (P<0.05). To analyze our results from co-IP with ZO-1, we evaluated the equality of the variances in the groups by Levene test, which determined the type of t-test used for analyslis. All results are reported as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

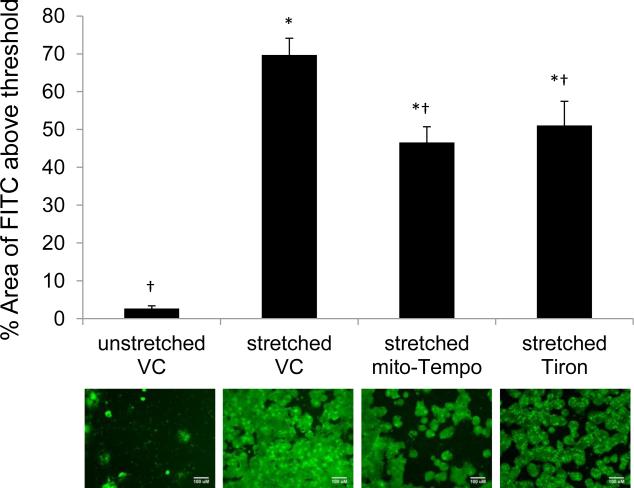

Permeability, as represented by FITC bound to the silastic membranes, was significantly increased in RAEC after cyclic stretch of 37% ΔSA for 10min at 0.25Hz (Figure 1), from 2.7±0.7 to 70±4.4 percent of the image field. Pretreatment of mito-Tempo, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, and Tiron, a superoxide scavenger, significantly reduced the stretch increased permeability to 47±4.1 and 51±6.4 percent of the image field, respectively. Unlike our previous report using a less sensitive BODIPY-ouabain method for measuring permeability (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013, Song, Davis et al. 2015), superoxide scavenging did not completely mitigate the stretch-induced permeability increases in RAECs completely, because treated groups had detectable permeability levels greater than unstretched monolayers (2.7±0.7 percent of the image field). There was no significant difference between mito-Tempo and Tiron as a protective intervention during stretch.

Figure 1.

Percent Image Field Area of FITC tagged streptavidin in rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayer (RAEC) during cyclic stretch (37% ΔSA, 10min, 0.25Hz). Mito-Tempo (500μM) and Tiron (10mM) are treated for 2hrs prior to stretch. VC=DMSO vehicle controls. ANOVA and Tukey Kramer as post-hoc analysis and * and † indicate significant difference from uns-VC and str-VC (n=3~5, p<0.05). Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars indicate 100μm in FITC-stained images.

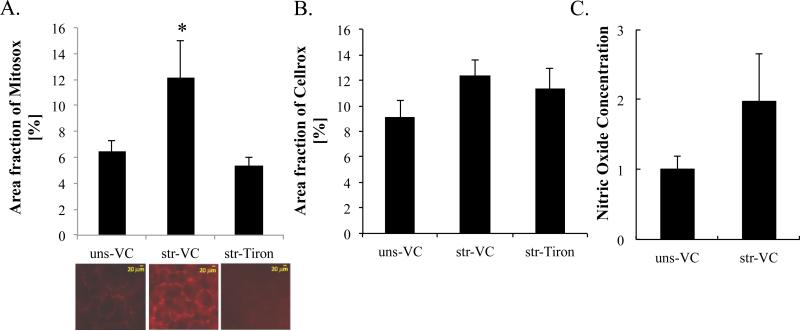

Mitochondrial superoxide (MitoSOX) signal was significantly increased by stretch (Figure 2A) from 6.5±0.76 to 12±2.8 percent of the image field. Superoxide scavenger Tiron prevented any significant stretch-induced increases in MitoSOX signal (5.34±0.66 percent of the field), similar to our previous reports for RAEC monolayers (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). Reactive oxygen species, as measured by CellROX, was not increased significantly in PCLS by cyclic stretch of 37% ΔSA for 1 hr at 0.25Hz (Figure 2B). Nitric oxide secretion in media was increased by stretch as we previously reported in RAEC monolayers (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013), but did not reach significance in PCLS (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Stretch-induced oxidative stress in precision cut lung slices (PCLS). Superoxide produced by mitochondria and total cellular reactive oxygen species were estimated from (A) MitoSOX (n=6~12: number of PCLSs) and (B) CellROX (n=9~13: PCLSs) stained images, respectively. PCLS were treated with Tiron (10mM) for 2hr prior to stretch (37% ΔSA, 1 hr, 0.25Hz). (C) Nitric oxide released into the medium during stretch (n=12: number of PCLSs). ANOVA with Tukey Kramer as a post-hoc analysis was applied. * indicates statistical significance from unstretched (uns) vehicle controls (VC) and stretched (str) with Tiron (p<0.05).

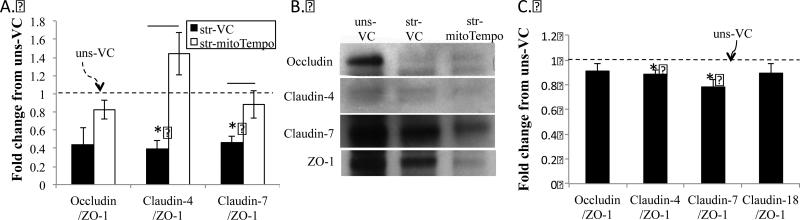

Using co-immunoprecipitation of ZO-1, we estimated ZO-1 bound tight junction proteins in stretched and unstretched PCLS and RAEC (Figure 3). In both preparations, cyclic stretch caused significant dissociation of Claudin 4 and 7 to approximately 40 percent of unstretched levels in PCLS stretched for 1 hour (39±10 and 46±7, respectively) and 80-90% of unstretched levels in RAECs stretched for 10 minutes (89±3 and 78±6, respectively). In contrast, occludin dissociation was not significant in either preparation (44±18 and 91±6 for PCLS and RAEC, respectively). Pretreatment of PCLS with mito-Tempo prevented stretch induced Claudin 4 and 7 dissociations from ZO-1, such that ZO-1 bound protein content was not significantly different from unstretched values (144±24 and 88±15 percent of unstretched values for Claudin 4 and 7).

Figure 3.

Dissociation of tight junction (TJ) proteins from ZO-1 in PCLS and RAEC. PCLS (n=4 rats) were treated with vehicle (black bars) or Mito-Tempo (500μM, white bars) for 2hrs prior to mechanical stretch (str) at 37% ΔSA for 1hr at 0.25 Hz. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed with ZO-1 as a bait protein, and Claudin-4, 7, and Occludin are probed by immunoblot. (B) Densitometry from immunoblots. (C) Densitometry from similar co-IP studies performed in RAECs (n=4 rats) with the same cyclic stretch magnitude for 10 min. VC=DMSO vehicle controls. * indicates significant difference from unstretched-VC. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

We have translated our in vitro findings and confirmed that large lung deformation increases permeability via release of reactive oxygen species using a deliberate, hierarchical manner using multiple platforms: primary epithelial monolayers, lung tissue slices, and intact rats. We conclude that the PCLS is a valuable lung preparation; more complex than monolayers, they offer the opportunity to study the role of mechanical factors that influence lung barrier dysfunction. In this communication, we show that large deformations increase permeability in alveolar epithelial monolayers and dissociate TJ proteins in both PCLSs and RAEC monolayers, similar to our previous reports of increased lung permeability and decreased compliance in intact rats ventilated at large tidal volumes (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013, Yehya, Xin et al. 2015). In stretched RAEC monolayers (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013) and PCLSs, we find that mitochondrial superoxide (Mitosox) was increased more than broadly targeted ROS (CellROX). Specifically, we find that large, physiologic cyclic stretch magnitudes nearly double the level of mitochondrial superoxide in PCLSs with resident type I and type II RAECs (see Figure 3 in (Davidovich, Huang et al. 2013)) compared to unstretched PCLSs, similarly to stretched rat alveolar epithelial monolayers with type I like features (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). Previously we reported that in vivo and in vitro increases in permeability with stretch are ROS-dependent (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013, Yehya, Xin et al. 2015), and now present that these stretch levels also dissociate TJ proteins in epithelial monolayers and lung slices. In all three platforms we have confirmed that antioxidants Tiron or mito-Tempo prevented stretch-induced barrier disruption. Both interventions were effective in preventing barrier dysfunction; because Tiron scavenges nonspecific superoxide in RAEC monolayer during stretch and mitoTempo inhibits mitochondrial superoxide production, we conclude that mitochondrial superoxide has a predominant effect on permeability and dissociation of TJ proteins from ZO-1. Given the similarity in our findings across cell monolayers, lung slices and intact lungs, we find little influence of other resident cells in the intact lung slices and lungs, we speculate that the epithelial Type I cells are the primary source of superoxide associated with large lung inflations. We propose that future work should investigate optimizing barrier function protection during large deformations via reduction of mitochondrial superoxide release.

In the lung, cyclic stretch has been associated with ROS production in other cell types. For example, after 2 hrs of cyclic stretch (20% strain), human 16HBE and A549 epithelial cell lines and Type II RAECs produced superoxide (Chapman, Sinclair et al. 2005). In the 16HBE cells, the stretch-induced generation of superoxide was partially inhibited by mitochondrial complex 1 inhibitor Rotenone. Mitochondrial mediated cyclic-stretch induced generation of ROS was also reported in endothelial cells and osteoblast-like HT-3 cells (Ali, Pearlstein et al. 2004, Yamamoto, Fukuda et al. 2005, Ali, Mungai et al. 2006). In addition, cyclic stretch triggered nitric oxide (NO) release to cell culture medium in primary human bronchial epithelial cells (Mohammed, Nasreen et al. 2007) and pulmonary vascular endothelial cells in situ (Kuebler, Uhlig et al. 2003), as well as in other types of cells (Takeda, Komori et al. 2006, Upton, Hennerbichler et al. 2006), but we have not found significant stretch-induced NO release in RAEC monolayers (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013, Yehya, Xin et al. 2015) or lung slices, and conclude that NO release may be a cell-type specific response to stretch.

In vivo, we have showed that Tiron pretreatment dramatically decreased the lung permeability in rats during large tidal volume ventilation (25 cc/kg for 2 hours), as measured by accumulation of intravenously injected FITC-conjugated albumin in the broncho-alveolar lavage fluid, compared with untreated ventilated animals (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013). In fact, permeability in Tiron treated ventilated animals was not different than in untreated spontaneously breathing rats. Mito-tempo has also been used safely in vivo to scavenge superoxide in animal models of hypertension and cancer (Dikalova, Bikineyeva et al. 2010, Nazarewicz, Dikalova et al. 2013), and future studies could examine therapeutic efficacy in VILI. Although the mechanisms by which stretch-associated ROS increases lung permeability have yet to be elucidated, in Caco-2BBE intestinal epithelial monolayers, NO decreased the transepithelial resistance (TER), dilated the tight junctions (TJs), adherence junctions and desmosomes, and disrupted the actin association with the plasma membrane (Salzman, Menconi et al. 1995). Exposure of Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells to hydrogen peroxide or NO caused significant impairment in mitochondrial respiration that was associated with derangement of TJ proteins occludin, β–catenin, and ZO-1 (Cuzzocrea, Mazzon et al. 2000). To date, no one has investigated if TJ protein structural dissociation may be responsible for the increase in epithelial permeability in the lung caused by ROS exposure, and future work should focus on defining the mechanistic pathways that link stretch, ROS generation/exposure, and lung barrier dysfunction.

Previously we reported that NF-κB signaling mediates ROS release during stretch of RAEC monolayers (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013), and that p65 translocated into the nucleus of type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells in stretched PCLSs (Davidovich, Huang et al. 2013), demonstrating that activation of the NF-κB pathway is important in PCLS as well. Using the same published methods, in a limited number of PCLS, we confirmed that stretch-induced p65 translocation to the nucleus was inhibited by Tiron pre-treatment to scavenge superoxide and by ERK inhibition with U0126 (supplemental Figure S1). Because others have demonstrated that cyclic-strain induced activation of NF-κB mediates oxidative stress responses in umbilical vein endothelial cells (Ali, Pearlstein et al. 2004), and primary pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (Davidovich, DiPaolo et al. 2013), we suggest that future studies detail the role of the NF-κB pathway TJ dissociation during the cyclic stretch .

There are several limitations to our study. First, our investigation of TJ dissociation was restricted to the ZO-1 protein, and did not address dissociation of TJ proteins from ZO-2 in alveolar epithelium (Umeda, Ikenouchi et al. 2006). However, Koval reported in primary RAECs on extracellular matrix-coated membranes maintained in culture conditions to promote transformation from Type II to Type I phenotype have increasing levels of ZO-1 protein expression and decreasing ZO-2 protein between days 2 and 5 in culture (Koval, Ward et al. 2010). Because RAECs demonstrate many characteristics of Type I cells by 4-5 days in culture, we speculate that ZO-1 may be more abundant than ZO-2 in RAEC type I epithelial cell TJs, which form the primary epithelial barrier in the lung (Mitic and Anderson 1998). Second, our study limited its focus of TJ dissociation to those between ZO-1 and other proteins, and did not examine the claudin-claudin and occludin-occludin homotypical TJ protein binding. Importantly, ZO-1 has been reported as an essential component for TJ complex in mammalian epithelial cells (Nagaoka, Udagawa et al. 2012), underscoring that ZO-1 dissociation with TJ protein may have a larger role in increased permeability than breakage of homotypical TJ protein bonds. We conclude that our approach, quantifying stretch-induced TJ protein dissociation from ZO-1, is a reasonable indirect measurement of increased permeability in PCLS, and we recommend future studies to investigate contributions of other TJ protein relationships in stretch-associated barrier disruption.

In summary, our novel precision-cut lung slices offer a unique translational platform between monocultures of primary cells and intact animals to study the mechanisms associated with ventilator-induced acute lung injury and opportunities for injury intervention, using TJ dissociation as a surrogate for alveolar epithelial barrier disruption. Future studies should identify which types of cells in the lungs and TJ protein couplings respond to oxidative stress, to identify opportunities for treatment of ventilator induced lung injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research support was provided by NIH NHLBI grant R01-HL57204. The authors are grateful to Jesi Kim, James Butler and Erica Hummel for technical assistance with lung slice preparation and image analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Revised paper submitted to The Special Issue of the Journal of Biomechanics (JBM) on “Motility and dynamics of living cells in health, disease and healing”

Conflict of interest statement

The authors (Song, Davidovich, Lawrence, and Margulies) declare that they have no commercial associations or sources of support that might pose a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ali MH, Mungai PT, Schumacker PT. Stretch-induced phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in endothelial cells: role of mitochondrial oxidants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291(1):L38–45. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00287.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MH, Pearlstein DP, Mathieu CE, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial requirement for endothelial responses to cyclic strain: implications for mechanotransduction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287(3):L486–496. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00389.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacallao R, Garfinkel A, Monke S, Zampighi G, Mandel LJ. ATP depletion: a novel method to study junctional properties in epithelial tissues. I. Rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Science. 1994;107(Pt 12):3301–3313. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C, Fukuda N, Song Y, Ma T, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-4 knockout mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103(4):555–561. doi: 10.1172/JCI4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Matter K. Transmembrane proteins of tight junctions. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2000;11(4):281–289. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basuroy S, Seth A, Elias B, Naren AP, Rao R. MAPK interacts with occludin and mediates EGF-induced prevention of tight junction disruption by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J. 2006;393(Pt 1):69–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borok Z, Verkman AS. Lung edema clearance: 20 years of progress: invited review: role of aquaporin water channels in fluid transport in lung and airways. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(6):2199–2206. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01171.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower RG, Rubenfeld GD. Lung-protective ventilation strategies in acute lung injury. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S312–316. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057909.18362.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh K, Cohen T, Margulies S. Stretch Increases Alveolar Epithelial Permeability to Uncharged Micromolecules. Am J. Physiol-Cell. 2006 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00355.2004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh KJ, Cohen TS, Margulies SS. Stretch increases alveolar epithelial permeability to uncharged micromolecules. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290(4):C1179–1188. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh KJ, Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(6):C1801–C1808. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh KJ, Oswari J, Margulies SS. Role of stretch on tight junction structure in alveolar epithelial cells. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 2001;25(5):584–591. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KE, Sinclair SE, Zhuang D, Hassid A, Desai LP, Waters CM. Cyclic mechanical strain increases reactive oxygen species production in pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289(5):L834–841. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00069.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KE, Waters CM, Miller WM. Continuous exposure of airway epithelial cells to hydrogen peroxide: protection by KGF. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(1):71–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Merzdorf C, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. COOH terminus of occludin is required for tight junction barrier function in early Xenopus embryos. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;138(4):891–899. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TS, Cavanaugh KJ, Margulies SS. Frequency and peak stretch magnitude affect alveolar epithelial permeability. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):854–861. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00141007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TS, DiPaolo BC, Lawrence GG, Margulies SS. Sepsis enhances epithelial permeability with stretch in an actin dependent manner. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TS, Gray Lawrence G, Khasgiwala A, Margulies SS. MAPK activation modulates permeability of isolated rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayers following cyclic stretch. PloS one. 2010;5(4):e10385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, De Sarro A, Caputi AP. Role of free radicals and poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase in intestinal tight junction permeability. Mol Med. 2000;6(9):766–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich N, Chhour P, Margulies SS. Uses of Remnant Human Lung Tissue for Mechanical Stretch Studies. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2013;6(2):175–182. doi: 10.1007/s12195-012-0263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich N, DiPaolo BC, Lawrence GG, Chhour P, Yehya N, Margulies SS. Cyclic stretch-induced oxidative stress increases pulmonary alveolar epithelial permeability. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49(1):156–164. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0252OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich N, Huang J, Margulies SS. Reproducible uniform equibiaxial stretch of precision-cut lung slices. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;304(4):L210–220. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00224.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker BM, Nigam SK. Molecular structure and assembly of the tight junction. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274(1 Pt 2):F1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107(1):106–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipaolo BC, Davidovich N, Kazanietz MG, Margulies SS. Rac1 pathway mediates stretch response in pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305(2):L141–153. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00298.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPaolo BC, Lenormand G, Fredberg JJ, Margulies SS. Stretch magnitude and frequency-dependent actin cytoskeleton remodeling in alveolar epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(2):C345–353. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00379.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos CC, Slutsky AS. Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: a perspective. Invited Review. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;89(4):1645–1655. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 1998;157(1):294–323. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9604014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan EA. Lung inflation, lung solute permeability, and alveolar edema. Journal of Applied Physiology: Respiratory, Environmental & Exercise Physiology. 1982;53(1):121–125. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning AS. Organization and Regulation of the Tight Junction by the Actin-Myosin Complex. In: Cereijido M, Anderson JM, editors. Tight Junctions. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. pp. 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JL, Margulies SS. Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase activity in alveolar epithelial cells increases with cyclic stretch. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283(4):L737–746. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake R, Schlichtig R, Ulstad DR, Henschen RR. Barotrauma. Pathophysiology, risk factors, and prevention. Chest. 1987;91(4):608–613. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Varadharaj S, Giedt RJ, Zweier JL, Szeto HH, Alevriadou BR. Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species mediate heme oxygenase-1 expression in sheared endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329(1):94–101. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Hagge TE, Baumeister E, Bauer T, Schmiedeke D, Renne T, Wanner C, Galle J. Transmission of oxLDL-derived lipid peroxide radicals into membranes of vascular cells is the main inducer of oxLDL-mediated oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197(2):602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SS, He Q, Janczy JR, Elliott EI, Zhong Z, Olivier AK, Sadler JJ, Knepper-Adrian V, Han R, Qiao L, Eisenbarth SC, Nauseef WM, Cassel SL, Sutterwala FS. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2013;39(2):311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ER, Matthay MA. Acute lung injury: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Journal of aerosol medicine and pulmonary drug delivery. 2010;23(4):243–252. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Crandall ED. Effects of lung inflation on alveolar epithelial solute and water transport properties. Journal of Applied Physiology: Respiratory, Environmental & Exercise Physiology. 1982;52(6):1498–1505. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.6.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval M, Ward C, Findley MK, Roser-Page S, Helms MN, Roman J. Extracellular matrix influences alveolar epithelial claudin expression and barrier function. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42(2):172–180. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0270OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebler WM, Uhlig U, Goldmann T, Schael G, Kerem A, Exner K, Martin C, Vollmer E, Uhlig S. Stretch activates nitric oxide production in pulmonary vascular endothelial cells in situ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(11):1391–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-562OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuona E, Saldias F, Comellas A, Ridge K, Guerrero C, Sznajder JI. Ventilator-associated lung injury decreases lung ability to clear edema in rats. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(2):603–609. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9805050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Ryter SW, Xu J, Nakahira K, Kim HP, Choi AM, Kim YS. Carbon Monoxide Activates Autophagy via Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Formation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0352OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman RL, Kim KJ, Crandall ED. Alveolar Epithelial Barrier Properties. In: Crystal RG, West JB, editors. The Lung: Scientific Foundations. Lippincott - Raven; Philadelphia: 1997. pp. 585–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ma T, Fukuda N, Song Y, Matthay MA, Verkman AS. Lung fluid transport in aquaporin-5 knockout mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105(1):93–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthay MA, Bhattacharya S, Gaver D, Ware LB, Lim LH, Syrkina O, Eyal F, Hubmayr R. Ventilator-induced lung injury: in vivo and in vitro mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283(4):L678–682. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00154.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitic LL, Anderson JM. Molecular architecture of tight junctions. Annual Review of Physiology. 1998;60:121–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S, Sammani S, Wang T, Boone DL, Meyer NJ, Dudek SM, Moreno-Vinasco L, Garcia JG, Jacobson JR. Role of GADD45a in Akt Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination Following Mechanical Stress-Induced Vascular Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0447OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed KA, Nasreen N, Tepper RS, Antony VB. Cyclic stretch induces PlGF expression in bronchial airway epithelial cells via nitric oxide release. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(2):L559–566. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00075.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscedere JG, Mullen JB, Gan K, Slutsky AS. Tidal ventilation at low airway pressures can augment lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(5):1327–1334. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka K, Udagawa T, Richter JD. CPEB-mediated ZO-1 mRNA localization is required for epithelial tight-junction assembly and cell polarity. Nat Commun. 2012;3:675. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, Fitzgerald KA, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarewicz RR, Dikalova A, Bikineyeva A, Ivanov S, Kirilyuk IA, Grigor'ev IA, Dikalov SI. Does scavenging of mitochondrial superoxide attenuate cancer prosurvival signaling pathways? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(4):344–349. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswari J, Matthay MA, Margulies SS. Keratinocyte growth factor reduces alveolar epithelial susceptibility to in vitro mechanical deformation. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular & Molecular Physiology. 2001;281(5):L1068–1077. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu N. A Threshold Selection Method from Gray-Level Histograms. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SYSTEMS, MAN, AND CYBERNETICS SMC-9. 1979;(9):62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JC, Hernandez LA, Peevy KJ. Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury. Critical Care Medicine. 1993;21(1):131–143. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199301000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AS, Reigada D, Mitchell CH, Bates SR, Margulies SS, Koval M. Paracrine stimulation of surfactant secretion by extracellular ATP in response to mechanical deformation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00074.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard JD, Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;42:2s–9s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Itoh M, Furuse M, Inazawa J, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Mammalian occludin in epithelial cells: its expression and subcellular distribution. European Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;73(3):222–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman AL, Menconi MJ, Unno N, Ezzell RM, Casey DM, Gonzalez PK, Fink MP. Nitric oxide dilates tight junctions and depletes ATP in cultured Caco-2BBe intestinal epithelial monolayers. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(2 Pt 1):G361–373. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.2.G361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval R, Zhou B, Liebler JM, Kim KJ, Ann DK, Crandall ED, Borok Z. Claudin expression and localization in alveolar epithelial cells. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2002;165(A74) Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Shasby DM, Vanbenthuysen KM, Tate RM, Shasby SS, McMurtry I, Repine JE. Granulocytes mediate acute edematous lung injury in rabbits and in isolated rabbit lungs perfused with phorbol myristate acetate: role of oxygen radicals. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125(4):443–447. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Mechanical ventilation: lessons from the ARDSNet trial. Respir Res. 2000;1(2):73–77. doi: 10.1186/rr15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MJ, Davis CI, Lawrence GG, Margulies SS. Local influence of cell viability on stretch-induced permeability of alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. J. Cell and Mol Bioengineering. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s12195-015-0405-8. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson BR, Anderson JM, Braun ID, Mooseker MS. Phosphorylation of the tight-junction protein ZO-1 in two strains of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells which differ in transepithelial resistance. Biochemical Journal. 1989;263(2):597–599. doi: 10.1042/bj2630597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, Komori K, Nishikimi N, Nimura Y, Sokabe M, Naruse K. Bi-phasic activation of eNOS in response to uni-axial cyclic stretch is mediated by differential mechanisms in BAECs. Life Sci. 2006;79(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasaka S, Amaya F, Hashimoto S, Ishizaka A. Roles of oxidants and redox signaling in the pathogenesis of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(4):739–753. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies SS. Equibiaxial deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):L1173–1183. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumperlin DJ, Oswari J, Margulies SS. Deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells. Effect of frequency, duration, and amplitude. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):357–362. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9807003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T, Nigam SK. Tight junction proteins form large complexes and associate with the cytoskeleton in an ATP depletion model for reversible junction assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(26):16133–16139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuno K, Miura K, Takeya M, Kolobow T, Morioka T. Histopathologic pulmonary changes from mechanical ventilation at high peak airway pressures. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1991;143(5 Pt 1):1115–1120. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda K, Ikenouchi J, Katahira-Tayama S, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Nakayama M, Matsui T, Tsukita S, Furuse M, Tsukita S. ZO-1 and ZO-2 independently determine where claudins are polymerized in tight-junction strand formation. Cell. 2006;126(4):741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton ML, Hennerbichler A, Fermor B, Guilak F, Weinberg JB, Setton LA. Biaxial strain effects on cells from the inner and outer regions of the meniscus. Connect Tissue Res. 2006;47(4):207–214. doi: 10.1080/03008200600846663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Daugherty B, Keise LL, Wei Z, Foley JP, Savani RC, Koval M. Heterogeneity of claudin expression by alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29(1):62–70. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0180OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM, Ridge KM, Sunio G, Venetsanou K, Sznajder JI. Mechanical stretching of alveolar epithelial cells increases Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase activity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;87(2):715–721. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz HR, Dobbs LG. Calcium mobilization and exocytosis after one mechanical stretch of lung epithelial cells. Science. 1990;250(4985):1266–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.2173861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Fukuda K, Matsushita T, Matsukawa M, Hara F, Hamanishi C. Cyclic tensile stretch stimulates the release of reactive oxygen species from osteoblast-like cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;76(6):433–438. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-1188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehya N, Xin Y, Oquendo Y, Cereda M, Rizi RR, Margulies SS. Cecal ligation and puncture accelerates development of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308(5):L443–451. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.