Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common malignant brain tumor, and glioma stem cells (GSCs) are considered a major source of treatment resistance for glioblastoma. Identifying new compounds that inhibit the growth of GSCs and understanding their underlying molecular mechanisms are therefore important for developing novel therapy for GBM.

Methods

We investigated the potential inhibitory effect of isorhapontigenin (ISO), an anticancer compound identified in our recent investigations, on anchorage-independent growth of patient-derived glioblastoma spheres (PDGS) and its mechanism of action.

Results

ISO treatment resulted in significant anchorage-independent growth inhibition, accompanied with cell cycle G0-G1 arrest and cyclin D1 protein downregulation in PDGS. Further studies established that cyclin D1 was downregulated by ISO at transcription levels in a SOX2-dependent manner. In addition, ISO attenuated SOX2 expression by specific induction of miR-145, which in turn suppressed 3′UTR activity of SOX2 mRNA without affecting its mRNA stability. Moreover, ectopic expression of exogenous SOX2 rendered D456 cells resistant to induction of cell cycle G0-G1 arrest and anchorage-independent growth inhibition upon ISO treatment, whereas inhibition of miR-145 resulted in D456 cells resistant to ISO inhibition of SOX2 and cyclin D1 expression. In addition, overexpression of miR-145 mimicked ISO treatment in D456 cells.

Conclusions

ISO induces miR-145 expression, which binds to the SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR region and inhibits SOX2 protein translation. Inhibition of SOX2 leads to cyclin D1 downregulation and PDGS anchorage-independent growth inhibition. The elucidation of the miR-145/SOX2/cyclin D1 axis in PDGS provides a significant insight into understanding the anti-GBM effect of ISO compound.

Keywords: cell cycle, cyclin D1, glioblastoma sphere, isorhapontigenin, miR-145

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common primary malignant brain tumor in adults and has a poor prognosis.1 Standard treatment for newly diagnosed GBM includes maximum safe resection and concurrent chemoradiation followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide. At recurrence, which occurs an average of 7 months post initial diagnosis, GBM is usually treated with bevacizumab (a humanized anti-VEGF antibody). Despite these aggressive measures, the median survival of GBM is only 15–17 months.1–4 Challenges in treating GBM include difficulty in penetrating the blood-brain barrier by most cancer therapeutic agents, intrinsic heterogeneity of GBM, and existence of glioma stem cells (GSCs), which are particularly resistant to the current regimens.5–7 GSCs represent a small fraction of the GBM tumor and have features resembling neural stem cells. They can self-renew, grow as neurospheres, form tumors, and differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes.8 GSCs are believed to arise from neural stem cells, progenitor cells, or differentiated glial cells, driven by genetic mutations and epigenetic reprogramming.9–13 Development of treatment strategy aimed at eliminating glioma cells, especially GSCs, is critical in the development of effective therapies.

The Chinese herb Gnetum cleistostachyum has been used as an anticancer agent for thousands of years.14 The isorhapontigenin (ISO), a compound with a molecular weight of 258 Da and containing antioxidant properties, has been recently identified by our group to be the active anticancer compound found in the Chinese herb.14 Despite our limited knowledge regarding ISO's clinical implications, several studies have characterized the therapeutic potential of its chemical analogue, resveratrol. Resveratrol has been found to have minimal cytotoxicity to normal neural cells as opposed to its detrimental effects on GBM cells.15 Our previous studies have shown that ISO is 5–10 multiples more potent compared with resveratrol in its anticancer efficacy in many human cancer cell lines (data not shown); however, the therapeutic potential of ISO on GBM has not yet been explored.

Recent studies from our group have shown that ISO induces G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis in numerous cancer cell types.14 Its mechanisms of action include suppressing cyclin D1 expression, modulating expression of antiapoptosis protein XIAP,16 and inhibiting JNK/c-Jun/AP-1 activation.17 Given that MAPK and cyclin D1 deregulation are both essential for gliomagenesis, ISO presents itself as a valuable potential agent for GBM treatment. Herein, we evaluate the therapeutic potential of ISO in GBM cells and the patient-derived glioblastoma spheres (PDGS) that possess the classical properties of cancer stem cells18 and its underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Reagents

The SOX2 expression construct pSin-EF2-SOX2 was purchased from Addgene. The miR-145 expression construct pBluescript-miR-145 was kindly provided by Dr. Renato Baserga (Department of Cancer Biology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia).19 The miR-145 inhibitor was purchased from GeneCopoeia . The cyclin D1 promoter-driven luciferase reporter (cyclin D1 Luc) was used in our previous studies.14,20 The SOX2-3′UTR fragment and predicted miR-145 binding sites mutant sequence were amplified and cloned into pMIR-Report vector (Ambion) at the XhoI and HindIII sites, respectively, and the constructed vectors were named pMIR-SOX2-3′UTR-wt and pMIR-SOX2-3′UTR-mut. ISO with purity >99% was purchased from Rochen Pharma.

Cell Culture and Transfection

PDGS D456 and JX6 are described in Supplementary methods and previous publications.18,21–23 Transfections were carried out with specific cDNA constructs using PolyJet DNA In Vitro Transfection Reagent (SignaGen Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared, and Western blotting was conducted as described in Supplementary methods.

Anchorage-independent Growth Assay

Cells were exposed to various concentrations of ISO in soft agar assay and incubated for 2 weeks, and the cell colonies with >32 cells were scored as described in Supplementary methods.

Cell-cycle Analysis

The cells were harvested and fixed, then suspended in propidium iodide staining solution, and DNA content was determined by flow cytometry as described in Supplementary methods.

Reverse Transcription PCR and Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) after ISO treatment, and the cDNAs were synthesized with the Thermo-Script RT-PCR system (Invitrogen). The mRNA amount present in the cells was measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR. The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels, stained with Ethidium Bromide, and scanned for the images under UV light.

Total microRNAs were extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), reverse transcription was then performed using the miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen), and quantitative PCR was performed using miScript PCR Starter Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol; U6 was used as the endogenous normalizer. Cycle threshold (CT) values were determined, and the relative expression of microRNAs was calculated by using the values of 2−ΔΔCT.

Luciferase Assay

D456 cells were transfected with the indicated luciferase reporter in combination with the pRL-TK vector (Promega) as an internal control, and the luciferase activities were determined using microplate luminometer as described in Supplementary methods.

Statistical Analysis

The Student t test was used to determine statistical significance between sample groups. The significance threshold was set at P ≤ .05.

Results

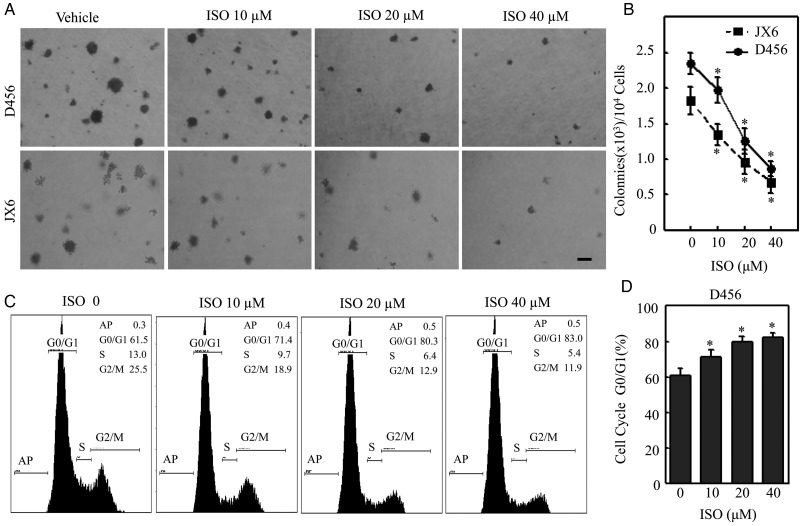

ISO Inhibited Anchorage-independent Growth and Induced G0-G1 Growth Arrest in PDGS

Although a number of our studies depicted ISO's therapeutic effects on human bladder cancer cells, its anticancer potential on PDGS has yet to be evaluated. Hence, to evaluate the potential impact of ISO on PDGS, we first examined the effects of ISO on anchorage-independent growth of PDGS in soft agar assay. ISO treatment markedly inhibited anchorage-independent growth in both D456 and JX6 GSC cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A), with subsequent quantitative analysis shown in Fig. 1B. Given that cellular anchorage-independent growth was demonstrated to be inhibited, we conducted a cell cycle analysis via flow cytometry. The results showed that ISO was also able to induce cell cycle G0-G1 growth arrest in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1C and D). Our results suggest that the inhibition of PDGS growth by ISO might be associated with its ability to induce cell G0-G1 growth arrest.

Fig. 1.

Isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibited anchorage-independent growth and induced G0/G1 growth arrest in patient-derived glioblastoma spheres (PDGS). (A and B) Representative images of anchorage-independent growth of D456 and JX6 cells in soft agar assay in the presence or absence of ISO as indicated. Scale bar was 200 μM. The results shown in (B) were obtained from 5 independent experiments. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (C and D) D456 cells were treated with ISO at indicated doses for 24 hours, and cell cycle was evaluated by flow cytometry. The result represents one of 3 independent experiments. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05).

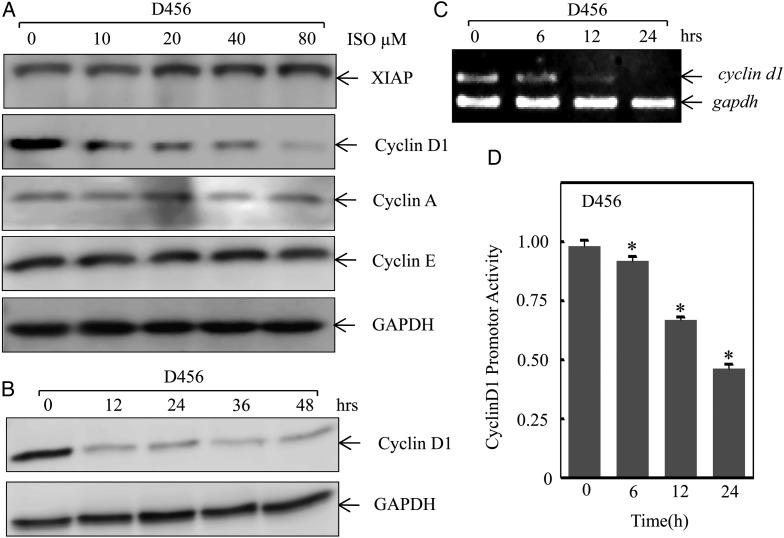

ISO Downregulated Cyclin D1 Protein Expression in PDGS

The inhibitive effect demonstrated by ISO on PDGS suggests that ISO may modulate cell growth-related mechanisms specifically involved in G0-G1 arrest. Our previous studies also demonstrated that ISO inhibits human bladder cancer cell growth through reduction of cyclin D1 and inhibition of XIAP expression.14,16 In order to elucidate such pathways, Western blotting was performed to screen for potential ISO downstream targets. As shown in Fig. 2A, ISO treatment specifically inhibited cyclin D1 protein expression, while there was no obvious change observed on the expression of cyclin A and cyclin E under the same experimental conditions. We noted that XIAP expression was moderately increased upon ISO treatment, which was not consistent with our previous report that ISO treatment downregulates XIAP transcription via inhibition of Sp1 in bladder cancer cells.16 We anticipate that the differential effect of ISO on XIAP expression might be due to the different responses to ISO between PDGS and bladder cancer cells, which was supported by the results showing ISO effects on Sp1 expression in PDGS16 (Fig. 3A). The cyclin D1 downregulation was observed in D456 cells treated with ISO (20 μmol/L) as early as 12 hours (Fig. 2B). To further investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the cyclin D1 downregulation, RT-PCR was performed to determine cyclin D1 mRNA expression level in D456 cells. D456 cells treated with ISO resulted in significant reduction of cyclin D1 mRNA in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C), suggesting that ISO might inhibit cyclin D1 protein expression at the transcription level. To test this notion, cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter (−1093) was transfected into D456 cells, and the transfectants were then treated with ISO for determination of ISO on cyclin D1 transcription. The results indicated that ISO treatment resulted in a significant inhibition of cyclin D1 promoter activity (Fig. 2D), which revealed that ISO downregulates cyclin D1 expression at the transcription level in D456 cells.

Fig. 2.

Isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibited cyclin D1 transcription. (A) D456 cells were treated with ISO at the indicated doses for 48 hours, and the cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of cyclin D1 protein expressions. (B) D456 cells were treated with of 20 μm of ISO for the indicated time points, and the cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of cyclin D1 protein expressions. (C) The mRNA expression levels of cyclin D1 in D456 cells were determined by RT-PCR after cells were treated with 20 μM of ISO for the indicated time points. (D) −1093 cyclin D1 luciferase reporter was transfected into D456 cells, and the transfectants were treated with 20 mM of ISO as indicated time periods for determination of cyclin D1 promoter-driven transcription activity. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05).

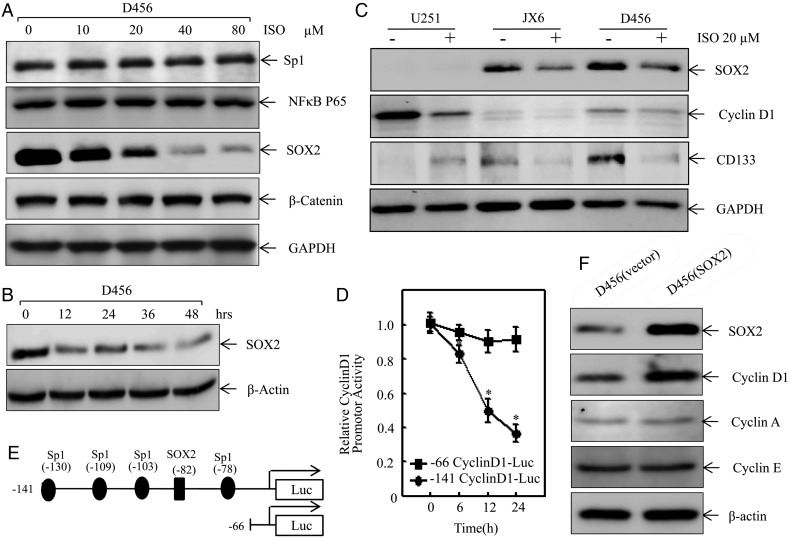

Fig. 3.

Isorhapontigenin (ISO) attenuated cyclin D1 transcription through impairing SOX2 expression. (A) D456 cells were treated with ISO at indicated doses for 48 hours, and the cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of protein expressions as indicated. (B) D456 cells were treated with of 20 μM of ISO for indicated time points, and the cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of SOX2 protein expressions. (C) PDGS (D456, JX6) and high-passage glioma U251 cells were treated with ISO (20 μM) for 24 hours, and the protein expression levels of cyclin D1, CD133, and SOX2 were determined by Western blotting. (D) −141 cyclin D1 luciferase reporter and its SOX2 binding site truncated deletion reporter (–66 cyclin D1-Luc) were transfected into D456 cells, respectively, and the transfectants were then exposed to 20 mM ISO for indicated time points to determine cyclin D1 promoter transcriptional activity. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (E) Schematic representation of the transcription factors binding sites in human cyclin D1 promoter region from −141 to −66. (F) D456 cells were transfected with SOX2 expression vector or control vector, and the transfectants were extracted at 24 hours post transfection. The cell extracts from D456(vector) and D456(SOX2) transfectants were subjected to Western blotting for determination of protein expressions as indicated.

ISO Regulated Cyclin D1 Transcription via Inhibition of SOX2 Expression

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of cyclin D1 regulation at transcription level, we determined the alteration of relevant transcription factor expression involved in the D456 cell response to ISO treatment. As shown in Fig. 3A, ISO treatment resulted in a dramatically dose-dependent reduction of SOX2 protein expression (Fig. 3A) but did not show an observable effect on expression of Sp1 and NF-κB p65. Moreover, ISO treatment did not affect protein expression of β-catenin, a transcription partner of SOX224 (Fig. 3A). The specific downregulation of SOX2 proteins was observed in D456 cells treated with ISO as early as 12 hours post treatment (Fig. 3B). We also tested whether this ISO inhibition was specific to SOX2 in PDGS compared with to high-passage glioma U251 cells. The results indicated that expression of SOX2 and CD133 was only observed in normal cultured PDGS (D456 and JX6) but not in U251 cells and that ISO treatment exhibited a dramatic inhibition of SOX2 and CD133 expression in PDGS, although ISO inhibition of cyclin D1 expression could be observed in both PDGS (D456, JX6) and high-passage glioma cells (U251 cells) (Fig. 3C). These results revealed that ISO inhibition of SOX2 and CD133 is specific to PDGS. It has been reported that SOX2 functions as transcription factor in many stages of mammalian development.25 Therefore, we next transfected D456 cells with a wild-type cyclin D1 promoter-driven luciferase reporter containing SOX2 binding sites (–141 cyclin D1-Luc) and a −141 cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter with SOX2 binding site truncated deletion (−66 cyclin D1-Luc), respectively. The transfectants were then treated with ISO for determination of cyclin D1 promoter-dependent transcriptional activity. The results showed that ISO treatment resulted in significant inhibition of cyclin D1 promoter transcriptional activity in the cells transfected with −141 cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter, while the inhibition was not observed in the cells transfected with −66 cyclin D1 promoter luciferase reporter (Fig. 3D). Those results indicated that the SOX2 binding site in cyclin D1 promoter is crucial for ISO inhibition of cyclin D1 promoter transcriptional activity as represented in the schematic diagram in Fig. 3E. Consistently, the role of SOX2 in regulation of cyclin D1 expression in D456 cells was also strongly supported by our results that ectopic expression of SOX2 elevated cyclin D1 protein expression markedly without affecting expression of cyclin A and cyclin E in comparison with that in vector transfectant (Fig. 3F). Our results demonstrated that ISO downregulates cyclin D1 expression at the transcription level through specific inhibition of SOX2 expression in PDGS, which is distinct from the molecular mechanism in human bladder cancer cells.14,16,17

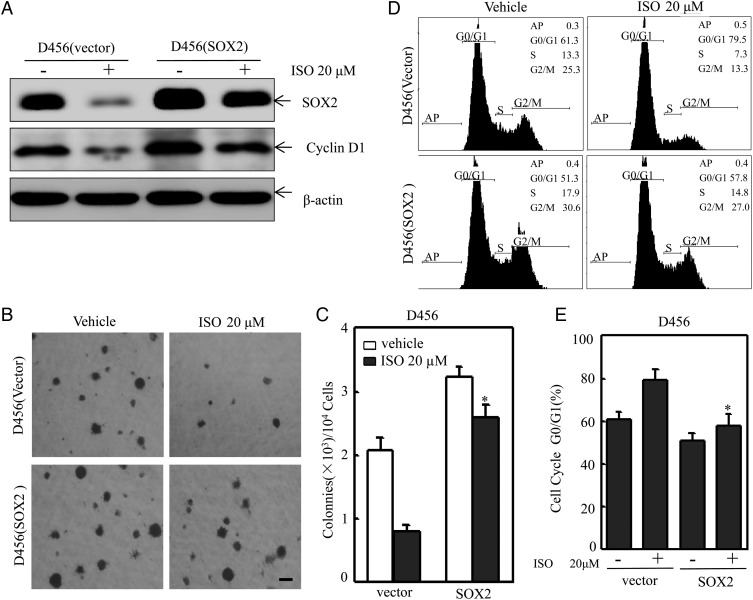

Overexpression of SOX2 Rendered D456 Cells Resistant to ISO Inhibition of Anchorage-independent Growth and the Induction of G0-G1 Growth Arrest

To evaluate the contribution of SOX2 downregulation to ISO inhibition of PDGS, D456 cells were transfected with SOX2 overexpression construct. The transfectants were then treated with ISO to determine how overexpressed SOX2 regulates anchorage-independent growth and cell cycle. As shown in Fig. 4A, ISO treatment did not show a marked inhibitory effect on exogenous expressed SOX2 protein expression, whereas it dramatically inhibited endogenous SOX2 protein expression in D456 cells (Fig. 4A). Consistently, ectopic expression of SOX2 also restored cyclin D1 protein expression as compared with that in D456 (vector) transfectants following ISO treatment (Fig. 4A) and reversed ISO inhibition of anchorage-independent growth of D456 cells (Fig. 4B and C) and G0-G1 growth arrest of D456 cells (Fig. 4D and E). These results demonstrated that SOX2 downregulation contributes to ISO inhibition of anchorage-independent growth and the induction of G0-G1 growth arrest in D456 cells.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of SOX2 reversed isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibition of anchorage-independent growth and the induction of G0/G1 growth arrest in D456 cells. (A) D456 cells were transfected with SOX2 expression construct, and the transfectants were then exposed to ISO at indicated concentrations for 24 hours. The cells were extracted, and cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of protein expressions. (B and C) The cell transfectants, as indicated, were subjected to soft agar assay for determination of their anchorage-independent growth capability. Scale bar was 200 μm. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (D and E) The cell transfectants, as indicated, were subjected to cell cycle analyses by flow cytometry. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05).

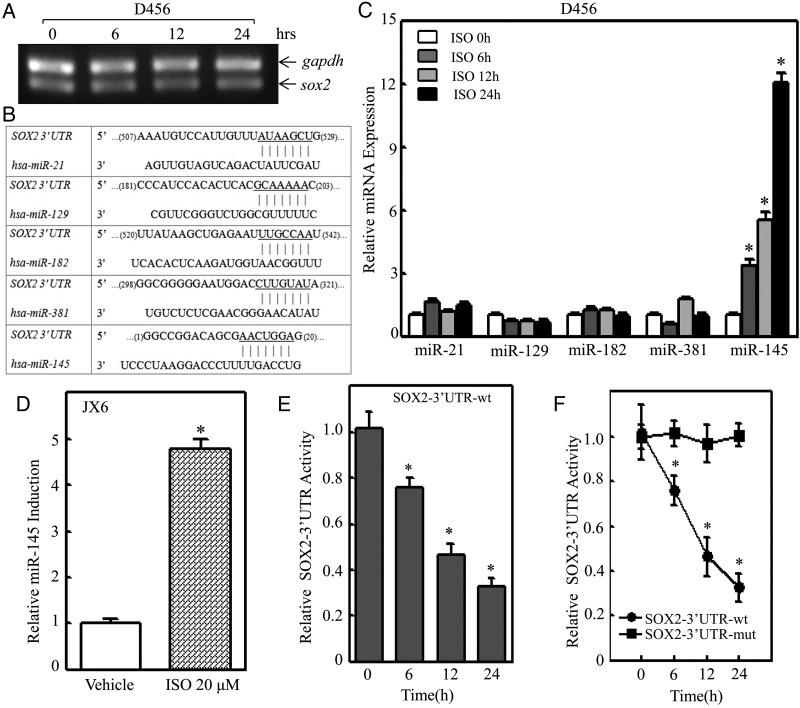

miR-145 Induction Was Crucial for ISO Inhibition of SOX2 Expression in PDGS

SOX2 could be regulated at multiple levels through a variety of mechanisms including transcriptional, mRNA stability, translational, and protein degradation. To test whether SOX2 is regulated at the level of either mRNA transcription or mRNA degradation, RT-PCR was employed to determine the effect of ISO on SOX2 mRNA expression. The results indicated that ISO treatment did not show any effect on SOX2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5A) and that SOX2 inhibition by ISO did not occur at mRNA transcription and/or mRNA degradation. Our results also showed that ISO only inhibited endogenous SOX2 but not exogenous SOX2 expression, thereby excluding possible degradation regulation of SOX2 protein by ISO. Therefore, we next examined possible ISO regulation of SOX2 at a protein translational level. Considering that miRNAs have been acknowledged as a translational inhibitor,26 we used the TargetScan database to analyze potential miRNA binding sites in the 3′UTR region of SOX2 mRNA. As shown in Fig. 5B, there were 5 potential miRNA binding sites including miR-21, miR-129, miR-182, miR-381, and miR-145 in the 3′UTR region of SOX2 mRNA. We next evaluated the expression levels of those potential miRNAs via qPCR in D456 cells exposed to ISO treatment. The results indicated that ISO treatment led to a significant induction of miR-145 without affecting the expression of miR-21, miR-129, miR-182, and miR-381 (Fig. 5C). The miR-145 induction by ISO treatment was also observed in JX6 cells (Fig. 5D). To test the potential effect of ISO on SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR activity, we transfected wild-type SOX2-3′UTR-luciferase reporter into D456 cells and treated the transfectants with ISO to evaluate ISO inhibition of SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR activity. The results showed that ISO treatment inhibited SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR activity in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 5E). However, the point mutation of miR-145 binding site in SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR-luciferase reporter led to complete loss of ISO inhibitory effect on SOX2 mRNA 3′UTR activity. (Fig. 5F). These results demonstrated that miR-145 is not only induced by ISO in PDGS but is also crucial for ISO inhibition of SOX2-3′UTR activity in PDGS, further revealing that miR-145 inhibits SOX2 protein translation by binding directly to the SOX2-3′UTR region. It has been reported that miR-145 can target SOX2 3′UTRs directly and affect SOX2 mRNA expression in human embryonic stem cells,27,28 whereas our results revealed that miR-145 induction by ISO inhibits SOX2 protein translation without affecting SOX2 mRNA expression in human PDGS D456 cells. This discrepancy could be due to differing responses to miR-145 in 2 different stages of cells.

Fig. 5.

miR-145 induction was crucial for isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibition of SOX2-3′UTR activity in D456 cells. (A) The mRNA expression levels of SOX2 in D456 cells were determined by reverse transcription PCR after cells were treated with ISO (20 µM) for indicated time points. (B) Schematic representation of potential miRNA binding sites in SOX2 mRNA-3′UTR were analyzed with TargetScan database. (C) D456 cells were treated with 20 mm ISO for indicated time points, and the alteration of microRNA expression levels was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (D) JX6 cells were treated with 20 μM of ISO for 24 hours, and the alteration of miR-145 expression in JX6 cells was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (E) SOX2-3′UTR luciferase reporter was transfected into D456 cells, and the transfectants were then exposed to ISO (20 µM) for indicated time points to determine ISO inhibition of SOX2-3′UTR activity. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (F) Wild-type SOX2-3′UTR luciferase reporter and its mutant reporter (SOX2-3′UTR-mut luciferase reporter) were transfected into D456 cells, respectively, and the transfectants were then exposed to 20 µM ISO for indicated time points to determine the role of miR-145 binding site in ISO inhibition of SOX2-3′UTR activity.

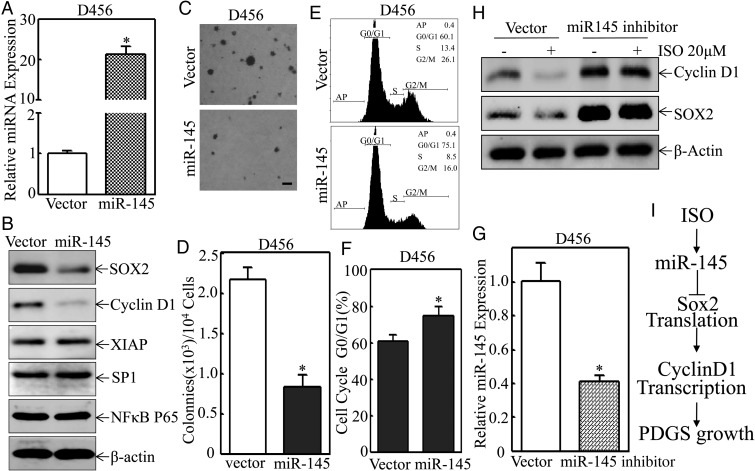

Ectopic Expression of miR-145 Showed Inhibition of Cyclin D1 Expression, Anchorage- independent Growth, and Induction of G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest in D456 Cells

To test whether miR-145 could mimic the biological effects observed in D456 cells treated with ISO, miR-145 expression construct was transfected into D456 cells, and the relative expression level of miR-145 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, transfection of miR-145 into D456 cells resulted in > 20-fold elevation of miR-145 expression and overexpression of miR-145, specifically impairing SOX2 and its downstream target cyclin D1 protein expression, but did not show observable inhibition of XIAP, Sp1, and NF-κB p65 expression. Ectopic expression of miR-145 also attenuated anchorage-independent growth of D456 cells in soft agar assay and induced G0/G1 cell cycle growth arrest in D456 cells (Fig. 6C–F). Consequently, knockdown of miR-145 expression, using its specific inhibitor, abolished ISO-induced downregulation of SOX2 and cyclin D1 expression in D456 cells (Fig. 6G and H). These results demonstrated that miR-145 induction by ISO treatment is responsible for its inhibition of SOX2 and cyclin D1 expression in PDGS, further mediating inhibition of anchorage-independent growth and anticancer activity of ISO compound.

Fig. 6.

Overexpression of miR-145 inhibited expression of SOX2, and cyclin D1 attenuated anchorage-independent growth and induced G0/G1 growth arrest in D456 cells. D456 cells were transfected with miR-145 expression construct or its control vector, and the relative miR-145 expression level was determined by quantitative real-time PCR 24 hours post transfection (A), or the cell extracts from the transfectants were subjected to Western blot for determination of protein expressions as indicated (B), or the cell transfectants were subjected to either soft agar assay for determination of their anchorage-independent growth (C and D) or flow cytometry for analysis of cell cycle distribution (E and F). Scale bar was 200 µM. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (G) D456 cells were transfected with miR-145 inhibitor or its control vector, and the relative miR-145 expression level was determined by quantitative real-time PCR at 24 hours post transfection. The symbol (*) indicates a significant difference (P < .05). (H) D456 cell transfectants as indicated were treated with isorhapontigenin (ISO) (20 µM) for 24 hours, and the cell extracts were subjected to Western blotting for determination of protein expressions. (I) Schematic mechanisms underlying ISO inhibition of anchorage-independent growth of patient-derived glioblastoma spheres.

Discussion

Cancer stem cells are critical for tumor initiation, progression, relapse, and resistance to chemoradiotherapy.29,30 It is crucial to explore novel treatment strategies that target the molecular components relevant to cancer stem cells. ISO was recently found to have an anticancer effect, although its mechanism remains unclear. Several studies have reported that ISO and its chemical analogue resveratrol elicit similar responses such as NF-κB inhibition, which suggests that ISO could utilize a similar mechanism for its anticancer effect (as shown for resveratrol).31–33 However, we recently demonstrated that ISO inhibits human bladder cancer cell growth by inhibiting XIAP/cyclin D1 expression without affecting the NF-κB pathway, indicating that ISO's anticancer activity may be through a mechanism distinct from resveratrol. Here, we showed that ISO induces D456 cells G0/G1 growth arrest via induction of miR-145, which downregulates SOX2 and cyclin D1. The anti-PDGS properties of ISO, as depicted in Fig. 6I, could serve as a base for further investigation.

It is well established that deregulation of cell cycle proteins facilitates tumor progression.34 Cyclin D1 combined with CDK4/6 activates phosphorylation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor, which frees the E2F transcription factors to continue cell cycle progression.35 It is not surprising that cyclin D1 deregulation is a common phenomenon in cancer and that overexpression of cyclin D1 is a hallmark of excessive cellular proliferation in many cancers including bladder, breast, cervix, colon, prostate, and skin.36,37,38–43 Cyclin D1 overexpression prevails over that of cyclin D2 and D3, thereby distinguishing cyclin D1 as the dominant cell cycle regulator.44 In lieu of specific cyclin D1 inhibitors, compounds such as ISO could specifically repress cyclin D1 expression without affecting other cyclin cell cycle regulators. Thus, ISO can be employed as a potential indirect “specific” inhibitor targeting cyclin D1 in both cancer cells and cancer stem cells.

Cyclin D1 is regulated at multiple stages through a variety of mechanisms including Sp1, NF-kB, PI3K/Akt, and MAPK.14,45–47 In addition, cyclin D1 is reported to be regulated by SOX2 in breast cancer and glioma cells.24,48 Based on our previous findings that ISO inhibits cyclin D1 through suppression of Sp1,14,16,17 we examined Sp1 expression in PDGS after ISO treatment and found that no significant change was detected. We further examined expression of SOX2 and found it to be significantly inhibited at the translational level after ISO treatment. These results raised the possibility that SOX2 mRNA might be regulated at the translational level, possibly by miRNAs.

SOX2 is a transcription factor playing an important role in neuronal development as well as in maintaining the stemness state of GSCs.48–50 During early stage embryonic development, SOX2 coordinates with Oct4 and determines the phenotypic fate of the differentiated offspring.51 Wicklow et al reported that SOX2 serves as a dominant determining factor for pluripotency by maintaining the expression of the other pluripotency factors such as Oct4, c-Myc, and Nanog.52 In GBM, forced co-expression of transcription factors POUF3, SOX2, SALL2, and OLIG2 reverts differentiated GBM cells to a GSC-like state. Furthermore, downregulation of SOX2 inhibits glioma stem cell growth in vitro and gliomagenesis in animal models.50 In the current study, we found that ISO treatment led to a dramatic downregulation of SOX2 protein expression and that SOX2 regulated cyclin D1 in PDGS.

miRNAs have been recently reported to regulate GSCs and gliomagenesis. For example, forced miR-145 expression inhibits growth, migration, and invasion of GSCs.53 Administration of miR-145 inhibits tumor growth and prolongs animal survival in GBM xenograft models.54 Additionally, miR-145 has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of HSVtk gene therapy in GBM by downregulating metastasis genes such as PLAUR, SPOCK3, ADAM22, SLC75, and FASCN1.55 Collectively, the well-established tumor suppressor activity of miR-145 substantiates the potential clinical effectiveness of ISO. The implication of miR-145′s potential role as a regulator of SOX2 in the ISO-mediated anticancer response presents a rather interesting prospect for GBM treatments. Since miR-145 synergizes with temozolomide plus radiotherapy,54 ISO is likely to mimic the enhanced anticancer response when given together with other treatment modalities. Given that SOX2 and cyclin D1 have been implicated in chemoresistance of cancer stem cells and carcinogenesis, the identification of cyclin D1 and SOX2 as integral components of the ISO anticancer response provides an invaluable venue for further investigation of ISO as an anti-GBM agent.

In conclusion, our studies have identified the inhibitory effect of ISO on growth of PDGS and provided novel insight into the mechanisms responsible for the anticancer effect of ISO. We showed that miR-145/SOX2/cyclin D1 axis is critical in the ISO-mediated inhibition of anchorage-independent growth of PDGS. The axis is a novel mechanism involved in ISO-mediated cancer inhibition. It is different from that reported by Fang et al, who demonstrated that ISO inhibited bladder cancer cell growth by inhibiting cyclin D1 expression through targeting Sp1 expression. In lieu of such a mechanism, ISO inhibits cyclin D1 through miR-145/SOX2 expression and thus exerts a similar cancer inhibitory effect in PDGS. ISO, as an antioxidant, is likely an upstream regulator of cancer growth in response to cues of cancer cell microenvironment. The molecular mechanisms of ISO-mediated PDGS inhibition warrants further investigations in order to fully understand the extent of ISO's anticancer activity.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was partially supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (CA112557 to C.H., CA177665 to C.H. and CA165980 to C.H.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Renato Baserga from the Department of Cancer Biology at Thomas Jefferson University for the gift of pBluescript-miR-145; Dr. Richard G. Pestell from Kimmel Cancer Center, Thomas Jefferson University, for the gift of cyclin D1 promoter-driven luciferase reporter.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A et al. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(1):5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Population-based studies on incidence, survival rates, and genetic alterations in astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(6):479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran B, Rosenthal MA. Survival comparison between glioblastoma multiforme and other incurable cancers. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17(4):417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das S, Srikanth M, Kessler JA. Cancer stem cells and glioma. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(8):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanai N, Alvarez-Buylla A, Berger MS. Neural stem cells and the origin of gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(8):811–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31(1):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1253–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(10):755–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J, Son MJ, Woolard K et al. Epigenetic-mediated dysfunction of the bone morphogenetic protein pathway inhibits differentiation of glioblastoma-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(1):69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dey M, Ulasov IV, Lesniak MS. Virotherapy against malignant glioma stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;289(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang Y, Cao Z, Hou Q et al. Cyclin d1 downregulation contributes to anticancer effect of isorhapontigenin on human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(8):1492–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Z, Shi S, Li H et al. Evaluation of resveratrol sensitivities and metabolic patterns in human and rat glioblastoma cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72(5):965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang Y, Yu Y, Hou Q et al. The Chinese herb isolate isorhapontigenin induces apoptosis in human cancer cells by down-regulating overexpression of antiapoptotic protein XIAP. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(42):35234–35243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao G, Chen L, Li J et al. Isorhapontigenin (ISO) inhibited cell transformation by inducing G0/G1 phase arrest via increasing MKP-1 mRNA Stability. Oncotarget. 2014;5(9):2664–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han X, Zhang W, Yang X et al. The role of Src family kinases in growth and migration of glioma stem cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;45(1):302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Rocca G, Shi B, Sepp-Lorenzino L et al. Expression of micro-RNA-145 is regulated by a highly conserved genomic sequence 3′ to the pre-miR. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(3):602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang W, Ma Q, Li J et al. Cyclin D1 induction through IkappaB kinase beta/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway is responsible for arsenite-induced increased cell cycle G1-S phase transition in human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9287–9293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman GK, Langford CP, Coleman JM et al. Engineered herpes simplex viruses efficiently infect and kill CD133+ human glioma xenograft cells that express CD111. J Neurooncol. 2009;95(2):199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaron RH, Elion GB, Colvin OM et al. Busulfan therapy of central nervous system xenografts in athymic mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1994;35(2):127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrarese R, Harsh GR, Yadav AK et al. Lineage-specific splicing of a brain-enriched alternative exon promotes glioblastoma progression. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):2861–2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Shi L, Zhang L et al. The molecular mechanism governing the oncogenic potential of SOX2 in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):17969–17978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weina K, Utikal J. SOX2 and cancer: current research and its implications in the clinic. Clin Transl Med. 2014;3:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G et al. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137(4):647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain AK, Allton K, Iacovino M et al. p53 regulates cell cycle and microRNAs to promote differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(2):e1001268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moghbeli M, Moghbeli F, Forghanifard MM et al. Cancer stem cell detection and isolation. Med Oncol. 2014;31(9):69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Hide T et al. Cancer stem cells in nervous system tumors. Oncogene. 2004;23(43):7267–7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Udenigwe CC, Ramprasath VR, Aluko RE et al. Potential of resveratrol in anticancer and anti-inflammatory therapy. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(8):445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Yang YL, Zhang H et al. Administration of the resveratrol analogues isorhapontigenin and heyneanol-A protects mice hematopoietic cells against irradiation injuries. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:282657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Marin MI, Guerrero RF, Garcia-Parrilla MC et al. Isorhapontigenin: a novel bioactive stilbene from wine grapes. Food Chem. 2012;135(3):1353–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274(5293):1672–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh RP, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Inositol hexaphosphate inhibits growth, and induces G1 arrest and apoptotic death of prostate carcinoma DU145 cells: modulation of CDKI-CDK-cyclin and pRb-related protein-E2F complexes. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24(3):555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristt D, Turner I, Koren R et al. Overexpression of cyclin D1 mRNA in colorectal carcinomas and relationship to clinicopathological features: an in situ hybridization analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2000;6(1):65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehn S, Tobin NP, Berglund P et al. Down-regulation of the oncogene cyclin D1 increases migratory capacity in breast cancer and is linked to unfavorable prognostic features. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(6):2886–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shariat SF, Ashfaq R, Sagalowsky AI et al. Correlation of cyclin D1 and E1 expression with bladder cancer presence, invasion, progression, and metastasis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1568–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajabi H, Ahmad R, Jin C et al. MUC1-C oncoprotein induces TCF7L2 transcription factor activation and promotes cyclin D1 expression in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(13):10703–10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satinder K, Chander SR, Pushpinder K et al. Cyclin D1 (G870A) polymorphism and risk of cervix cancer: a case control study in north Indian population. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;315(1–2):151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N et al. A cohort study of cyclin D1 expression and prognosis in 602 colon cancer cases. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(13):4431–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleischmann A, Rocha C, Saxer-Sekulic N et al. High-level cytoplasmic cyclin D1 expression in lymph node metastases from prostate cancer independently predicts early biochemical failure and death in surgically treated patients. Histopathology. 2011;58(5):781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burnworth B, Popp S, Stark HJ et al. Gain of 11q/cyclin D1 overexpression is an essential early step in skin cancer development and causes abnormal tissue organization and differentiation. Oncogene. 2006;25(32):4399–4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JK, Diehl JA. Nuclear cyclin D1: an oncogenic driver in human cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220(2):292–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimura T, Noma N, Oikawa T et al. Activation of the AKT/cyclin D1/Cdk4 survival signaling pathway in radioresistant cancer stem cells. Oncogenesis. 2012;1:e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouyang W, Li J, Ma Q et al. Essential roles of PI-3K/Akt/IKKbeta/NFkappaB pathway in cyclin D1 induction by arsenite in JB6 Cl41 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(4):864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Z, Zhang X, Yang Z et al. MiR-145 regulates PAK4 via the MAPK pathway and exhibits an antitumor effect in human colon cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427(3):444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berezovsky AD, Poisson LM, Cherba D et al. Sox2 promotes malignancy in glioblastoma by regulating plasticity and astrocytic differentiation. Neoplasia. 2014;16(3):193–206, 206 e119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikushima H, Todo T, Ino Y et al. Glioma-initiating cells retain their tumorigenicity through integration of the Sox axis and Oct4 protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(48):41434–41441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gangemi RM, Griffero F, Marubbi D et al. SOX2 silencing in glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells causes stop of proliferation and loss of tumorigenicity. Stem Cells. 2009;27(1):40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizzino A. Concise review: The Sox2-Oct4 connection: critical players in a much larger interdependent network integrated at multiple levels. Stem Cells. 2013;31(6):1033–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wicklow E, Blij S, Frum T et al. HIPPO pathway members restrict SOX2 to the inner cell mass where it promotes ICM fates in the mouse blastocyst. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(10):e1004618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi L, Wang Z, Sun G et al. miR-145 inhibits migration and invasion of glioma stem cells by targeting ABCG2. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16(2):517–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang YP, Chien Y, Chiou GY et al. Inhibition of cancer stem cell-like properties and reduced chemoradioresistance of glioblastoma using microRNA145 with cationic polyurethane-short branch PEI. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1462–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SJ, Kim SJ, Seo HH et al. Over-expression of miR-145 enhances the effectiveness of HSVtk gene therapy for malignant glioma. Cancer Lett. 2012;320(1):72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.