Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI in differentiating tumor progression and radiation injury in patients with indeterminate enhancing lesions after radiation therapy (RT) for brain malignancies.

Methods

Patients with indeterminate enhancing brain lesions on conventional MRI after RT underwent brain DCE-MRI and PET-CT in a prospective trial. Informed consent was obtained. Lesion outcomes were determined by histopathology and/or clinical and imaging follow-up. Metrics obtained included plasma volume (Vp) and volume transfer coefficient (Ktrans) from DCE-MRI, and maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) from PET-CT; lesion-to-normal brain ratios of all metrics were calculated. The Wilcoxon rank sum test and receiver operating characteristic analysis were performed.

Results

The study included 53 patients (29 treated for 29 gliomas and 24 treated for 26 brain metastases). Progression was determined in 38/55 (69%) indeterminate lesions and radiation injury in 17 (31%). Vpratio (VP lesion/VP normal brain, P < .001), Ktransratio (P = .002), and SUVratio (P = .002) correlated significantly with diagnosis of progression versus radiation injury. Progressing lesions exhibited higher values of all 3 metrics compared with radiation injury. Vpratio had the highest accuracy in determining progression (area under the curve = 0.87), with 92% sensitivity and 77% specificity using the optimal, retrospectively determined threshold of 2.1. When Vpratio was combined with Ktransratio (optimal threshold 3.6), accuracy increased to 94%.

Conclusions

Vpratio was the most effective metric for distinguishing progression from radiation injury. Adding Ktransratio to Vpratio further improved accuracy. DCE-MRI is an effective imaging technique for evaluating nonspecific enhancing intracranial lesions after RT.

Keywords: DCE MRI perfusion, 18F-FDG PET-CT, radiation injury

Radiation therapy (RT) has an essential role in providing local control and prolonging survival of patients with intracranial primary malignancies (gliomas) as well as those with brain metastases.1–4 While RT is effective in disease control, it often results in radiation injury at treatment sites, which may manifest months to years later.5 In patients treated for gliomas with standard fractionated RT and systemic therapy, the radiation injury rate has been reported to be 5%–10%.6 In the treatment of metastasis using single-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), radiation injury rates may reach 18% or greater.7,8

Conventional MRI is often unable to reliably distinguish between progression and radiation injury, as both may manifest with new and/or growing enhancing lesions.9,10 For patients with indeterminate findings on conventional MRI, treatment decision making is difficult, as progression usually demands a significant change in therapeutic approach to ensure tumor control.11,12 Although some patients (25% in the series reported upon here) do undergo surgical resection of enhancing lesions for neurologic symptom management and improvement of long-term outcome, allowing for definitive histopathologic diagnosis, resection is a risky invasive procedure and may not be suitable for all patients, especially those with multiple lesions, lesions in inaccessible locations, or progressive extracranial disease.13,14 In addition, histopathology is susceptible to sampling error. Therefore, an accurate, non-invasive imaging technique for diagnosing progression or radiation injury is needed.

Biologically, progression and radiation injury represent 2 different mechanistic processes: tumor progression causes increased enhancement due to tumor-induced angiogenesis and microvascular proliferation,15 while RT causes increased enhancement by inducing small-vessel endothelial damage and reducing microvasculature.16,17 Due to this fundamental pathophysiologic difference, advanced imaging modalities such as dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT have been advocated for the assessment of indeterminate enhancing lesions after RT. DCE-MRI correlates with microvascular density at angiography and histopathology18 and can quantify the inflammatory and vascular endothelial growth factor–mediated vascular changes that occur with tumor progression and radiation injury.19,20 FDG PET-CT has been shown to be useful in differentiating progression and radiation injury through metabolic differences, with higher uptake in active tumor cells.21 DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT are commonly performed for the diagnosis of progression and radiation injury in patients with enhancing lesions of indeterminate etiology after RT, but their comparative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity remain uncertain. In this study, we prospectively evaluated the efficacy of DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT in predicting whether new or worsening enhancing brain lesions seen after RT represented progression or radiation injury.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

This prospective trial was approved by the local institutional review board and privacy board (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT01604512). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, pathological or clinical/radiological diagnosis of a primary or secondary brain tumor, completion of RT, and new and/or increasing enhancing brain lesion(s) at the treated site considered indeterminate for progression versus radiation injury by the neuroradiologist and clinician. The exclusion criterion was a contraindication to PET-CT or MRI scan or gadolinium contrast. Fifty-three patients (35 male and 18 female) with 55 indeterminate lesions and mean and median age of 57 years (range, 19–81) were enrolled.

DCE-MRI and PET-CT examinations were performed ≤12 weeks from the diagnosis of the indeterminate lesion and ≤12 weeks of each other, with either the DCE-MRI or the PET-CT acquired first. The accrual period for this study was from June 2012 through January 2014.

Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI Acquisition and Analysis

Patients were scanned on 1.5T or 3T scanners (Signa HDxt/Excite, Discovery 450/750, GE Healthcare) using an 8-channel head coil. Images acquired in multiple planes were standard T1-weighted (repetition time/echo time [TR/TE], 525/7 ms for 1.5T; 1800/7 ms for 3T), T2-weighted (TR/TE, 4000/102 ms for 1.5T; 3100/101 ms for 3T), diffusion-weighted (TR/TE, 8000/85 ms for 1.5T and 3T), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (TR/TE, 8000/160 ms for 1.5T; TR/TE, 9000/120 ms for 3T), susceptibility-weighted (TR/TE, 5000/25 ms for 1.5T; 38/23 ms for 3T), and contrast T1-weighted (TR/TE, 560/8 ms for 1.5T; 1842/7 ms for 3T).

T1-weighted DCE perfusion data were acquired using an axial 3D echo-spoiled gradient-echo sequence: TR, 4–5 ms; TE, 1–2 ms; flip angle, 25 degrees; slice thickness, 5 mm; field of view, 24 cm. Ten to 14 slices were acquired to cover the entire lesion volume. The time between phases (temporal resolution) was 5–6 sec per volume with 40 phases, 10 before and 30 immediately after i.v. bolus administration of a single dose of contrast material (0.2 mL/kg to maximum 20 mL gadopentetate dimeglumine; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals), total scan time 3 min 20 sec to 4 min. Axial contrast T1-weighted images were also obtained to match the DCE images. The raw data were transferred to an offline image processing workstation.

A board-certified neuroradiologist with 8 years of neuroimaging experience processed the DCE-MRI data in nordicICE (NordicNeuroLab). Using a 2-compartment model with kinetic modeling and arterial input function–based vascular deconvolution as proposed by Murase,22 maps were calculated of plasma volume (Vp), extravascular extracellular distribution volume (Ve), volume transfer coefficient between plasma and extravascular extracellular space (Ktrans = distribution into tissue; Kep = distribution away from tissue), and area under the perfusion time curve (AUPC). Each map was overlaid onto the matching contrast T1-weighted image, and DCE analysis was performed by placing 3–5 small fixed-diameter (50–75 mm2) regions of interest (ROIs) targeted to the most visually apparent abnormalities in the lesion on each perfusion color map. This method of analysis has been described as providing the most accurate and reproducible results.23–25 Areas of hemorrhage, calcification, cystic/necrotic change, and vessels were explicitly excluded by careful review of all available MRI sequences for each case, particularly the susceptibility-weighted imaging and pre-contrast T1 images.

For each individual perfusion color map, the most abnormally elevated of the 3–5 measurements was selected and then normalized by placing a fixed-diameter (50–75 mm2) ROI in the normal contralateral white matter and calculating the ratio of the lesion measurement to the normal white matter measurement; the ratios (hereafter referred to as Vpratio, Veratio, Ktransratio, Kepratio, and AUPCratio) were recorded for analysis..

Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT Protocol and Analysis

Ten millicuries of fluorine-18 FDG was i.v. injected, with the patient remaining seated in the injection room for 60 min. The patient was then positioned on a PET-CT scanner (Discovery STE, GE Healthcare). A spiral CT was acquired using a full helical acquisition at 1 sec/rotation, 30 mA, 140 kV; slice thickness, 5 mm. Immediately upon completion of the CT, a 10-min 3D PET scan was acquired. CT and PET data were reconstructed using a 30-cm field of view. A radiologist board certified in radiology and nuclear medicine with 9 years of PET-CT experience defined ROIs for the lesion and normal brain. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of the lesion and normal brain were measured. The brain FDG PET-CT was windowed to visualize the focal FDG avidity associated with the known brain lesion on MRI, then an ROI was placed to encompass the entire area of abnormal FDG avidity. SUVmax was measured from the voxel with the highest SUV within this ROI. Calculation of lesional SUVmax was reproducible, as the voxel with the highest SUV was consistently within a range of possible ROIs. A second ROI was then drawn in comparable contralateral normal brain to measure SUVmax for normal brain background. The ratio of lesion SUVmax and normal brain SUVmax (SUVratio) was then calculated and used for further analysis.

Lesion Diagnosis

When available, histopathology after resection of the indeterminate enhancing lesion was used to determine diagnosis. Progression was determined by the presence of any amount of tumor in the resected lesion. Radiation injury was determined by the complete absence of any identifiable tumor. For patients with nonhistopathologic diagnoses, determination of progression or radiation injury was made using modified criteria from the RANO (Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology) working group.26 Progression was determined by continued increase in size of the enhancing lesion (≥25% in sum of product of perpendicular diameters) or if the patient experienced progressive clinical worsening of neurologic function requiring salvage therapy. Radiation injury was determined by the absence of clinical worsening and the spontaneous stabilization or decrease of the enhancing lesion on subsequent MRI scans for a minimum of 6 months without new therapy.27 Lesion diagnosis was made by an experienced radiation oncologist blinded to the DCE-MRI and PET-CT data.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical characteristics were compared between patients with gliomas and patients with metastases using Fisher's test and the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was also used to determine the significance of correlations between DCE-MRI and PET-CT imaging metrics (Vpratio, Veratio, Ktransratio, Kepratio, AUPCratio, and SUVratio) and progression versus radiation injury. After Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing, the P-value was set to <.007 (P < .05 divided by 7 tests). Receiver operating characteristics analysis was performed for the imaging metrics found to be significant on the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and the area under the curve (AUC) was computed. Threshold values for the different imaging metrics were estimated by maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity. Subgroup analyses were also performed for the gliomas and the metastases.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-nine patients received RT for 29 gliomas, and the majority of these (97%) were treated with postoperative partial-brain RT (PBRT) to a median dose of 60 Gy (range, 26–60 Gy). Twenty-four patients received RT for 26 brain metastases; the treatments consisted of definitive SRS (42% of metastases; median dose, 21 Gy; range, 15–21 Gy), postoperative PBRT (12%; median dose, 30 Gy; range, 30–36 Gy), and various combinations of SRS, PBRT, and whole-brain RT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients, n = 53 | Patients with Gliomas, n = 29 | Patients with Brain Metastases, n = 24 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesions (%) | 55 | 29 (52.7) | 26 (47.3) | |

| Median age, y (range) | 57 (19–81) | 53 (19–72) | 63 (24–81) | .13 |

| Histology | ||||

| Astrocytoma* | ||||

| IV | 18 (33) | 18 (62) | ||

| III | 6 (11) | 6 (21) | ||

| II | 2 (4) | 2 (7) | ||

| Oligodendroglioma* | ||||

| III | 2 (4) | 2 (7) | ||

| II | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | ||

| Metastasis | ||||

| NSCLC | 7 (13) | 7 (27) | ||

| Breast | 7 (13) | 7 (27) | ||

| Melanoma | 5 (9) | 5 (19) | ||

| Other | 7 (13) | 7 (27) | ||

| Type of radiation therapy | ||||

| PBRT only | 31 (56) | 28 (97) | 3 (12) | |

| SRS only | 11 (20) | 11 (42) | ||

| PBRT + WBRT | 3 (5) | 2 (8) | ||

| SRS + WBRT | 8 (15) | 8 (31) | ||

| SRS + PBRT | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (8) | |

| Clinical outcome | <.001 | |||

| Tumor progression | 38 (69) | 27 (93) | 11 (42) | |

| Radiation injury | 17 (31) | 2 (7) | 15 (58) | |

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; WBRT, whole-brain RT.

*World Health Organization grade.

The median time between RT and detection of the indeterminate lesion was 9 months (range, 1–99 mo), with no significant difference between the glioma group (median, 9 mo; range, 1–99 mo) and the metastasis group (median, 10 mo; range, 3–40 mo; P = .83). The median time between detection of lesions in question and the first protocol scan was 1 month (range, 0–2.8 mo). The median time between the protocol DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT scans was 1 day (range, 0–84 d), with 36 patients (68%) completing the scans within 7 days; 41 patients (77%) completing them within 14 days; and 48 patients (91%) completing them within 30 days.

Clinical Outcomes Determination

Of the 55 indeterminate enhancing lesions assessed in the study, 38 (69%) were determined to be progression and 17 (31%) were determined to be radiation injury through either histopathologic examination after surgical resection (n = 14, 25%) or longitudinal clinical and radiological evaluation (n = 41 lesions, 75%). Progression was diagnosed more frequently for gliomas (93%) than for brain metastases (42%, P < .001, Table 1). The proportion of patients diagnosed with progression through surgical pathology did not differ significantly between the glioma cohort (23%) and the brain metastases cohort (28%, P = .76). At time of progression, patients with glioma were being treated with temozolomide (n = 7), bevacizumab (n = 6), 2 BKM120 (n = 2), carmustine (n = 1), carboplatin (n = 1), or irinotecan (n = 1). At time of progression, patients with metastases were being treated with bevacizumab (n = 2).

Correlation Between Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI/PET-CT Metrics and Clinical Outcomes

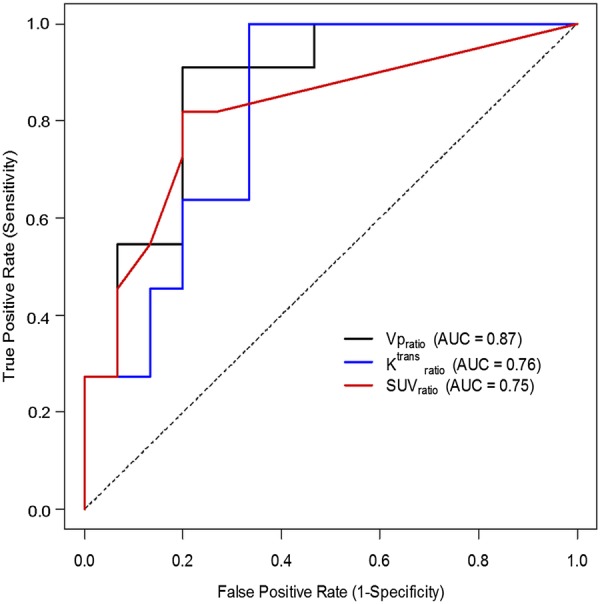

As summarized in Table 2, increased Vpratio (P < .001) and Ktransratio (P = .002) were significantly associated with progression, while Kepratio, Veratio, and AUPCratio were not (P > .17). Optimal threshold values were retrospectively determined from the data. When a Vpratio threshold of ≥2.1 was used to declare progression, sensitivity was 92% (ie, 35 of 38 lesions representing progression were correctly classified as progression) and specificity was 77% (the rate of correct classification of radiation injury as radiation injury). The use of a Ktransratio threshold of ≥3.6 to declare progression yielded sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 71%. The PET-CT SUVratio was also a significant predictor of progression (P = .002). The use of an SUVratio threshold of ≥1.2 to declare progression yielded sensitivity of 68% and specificity of 82% (Fig. 1). Representative cases are shown in Figs 2 and 3.

Table 2.

DCE-MRI and PET-CT imaging metrics used to determine accuracy in predicting disease progression vs radiation injury

| Variables | Disease Progression |

Radiation Injury |

Pa | AUC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | SE | Mean | Range | SE | |||

| DCE-MRI | ||||||||

| Vpratio | 6.2 | 1.5–41.9 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 1.1–7.8 | 0.4 | <.001 | 0.87 |

| Ktransratio | 31.8 | 0.4–363 | 10.9 | 6.3 | 0.3–28.4 | 2.1 | .002 | 0.76 |

| K21ratio | 91.8 | 1.0–700 | 24.6 | 54.7 | 0.7–250 | 19.6 | .21 | 0.61 |

| Veratio | 928 | 3.6–17 360 | 616 | 1068 | 1.4–12 275 | 770 | .17 | 0.62 |

| AUPCratio | 7.9 | 1.3–47.3 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 1.2–39.0 | 2.9 | .18 | 0.62 |

| PET-CT | ||||||||

| SUVratio | 1.6 | 1.0–4.2 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.9 | 0.1 | .002 | 0.75 |

aWilcoxon rank sum test.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for Vpratio, Ktransratio, and SUVratio demonstrating the optimal cutoffs to be 2.1, 3.6, and 1.2, respectively, in distinguishing between progression and radiation injury.

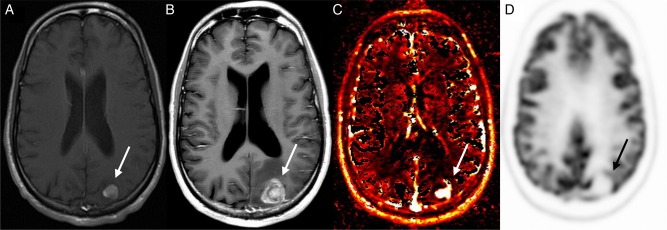

Fig. 2.

Patient example of tumor progression detected by DCE-MRI perfusion. Images obtained in a 30-year-old man with metastatic sarcoma who underwent SRS to a left parietal lobe metastasis. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image before treatment (A) shows an enhancing mass (arrow) that increases in size 6 months after treatment (B). Vp map of the enlarging mass (C) demonstrates increased perfusion; however, PET-CT showed no abnormal FDG uptake (D). Pathology confirmed progression.

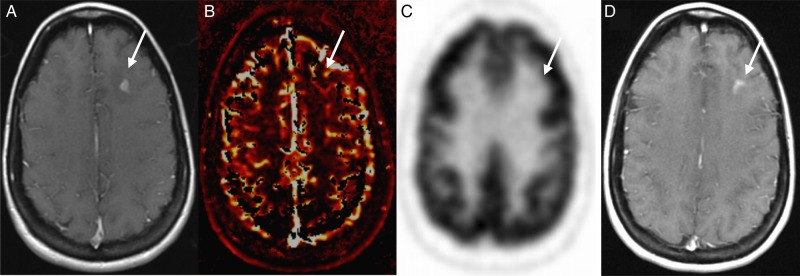

Fig. 3.

Patient example of radiation injury detected by DCE-MRI perfusion and PET-CT. Images obtained in a 39-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer who underwent SRS to a left frontal lobe metastasis. Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image (A) demonstrates an enhancing mass that had increased in size 1 year after SRS (arrow). DCE-MRI showed no increase in perfusion on the Vp map (B) and no increase in SUV on PET-CT (C). The lesion remained stable 1 year after it had enlarged (D) without any additional therapy and was determined to represent radiation injury.

Of the 38 lesions determined to be progression, 3 (8%) did not reach the Vpratio optimal threshold of 2.1, five (13%) did not reach the Ktransratio threshold of 3.6, and 12 (32%) did not reach the SUVratio threshold of 1.2. Of the 3 progressing lesions below threshold for Vpratio, 2 were also below threshold for Ktransratio and all 3 were below threshold for SUVratio. Of the 17 lesions determined to be radiation injury, 3 (18%) had an SUVratio > 1.2, four (24%) had a Vpratio > 2.1, and 5 (29%) had a Ktransratio > 3.6. Of the 3 radiation injury lesions above threshold for SUVratio, 2 were also above threshold for Vpratio, and 2 were above threshold for Ktransratio.

Discordance Between Predictions Made with DCE-MRI and PET-CT Metrics

When utilizing Vpratio ≥ 2.1 and SUVratio ≥ 1.2 as thresholds for predicting tumor progression, the results were discordant for 12 lesions. Vpratio correctly predicted tumor in 9 of these lesions (MR perfusion [MRP] and PET were performed on the same day for 4 lesions; PET preceded MRP for 4 lesions by 83, 34, 25, and 18 days; MRP preceded PET for 1 lesion by 1 day). There were no discordant cases of PET-CT correctly predicting tumor progression when Vpratio did not meet the threshold of 2.1. Vpratio correctly predicted radiation injury for 1 lesion that demonstrated an SUVratio ≥ 1.2 (SUVratio = 1.7; MRP and PET performed on the same day). PET-CT correctly predicted radiation injury in 2 lesions for which Vpratio predicted tumor progression (Vpratio = 7.77 and 2.52; both lesions in the same patient, MRP preceded PET by 18 days).

When a Ktransratio ≥ 3.6 and an SUVratio ≥ 1.2 were used as optimal thresholds for predicting tumor progression, the results were discordant for 18 lesions. Ktransratio correctly predicted tumor in 10 of these lesions (MRP and PET were performed on the same day for 5 lesions; PET preceded MRP for 4 lesions by 83, 34, 25, and 18 days; MRP preceded PET for 1 lesion by 1 day). Ktransratio correctly predicted radiation injury in 1 lesion that was predicted to be tumor by PET-CT (SUVratio = 1.9; PET preceded MRP by 1 day). PET-CT correctly predicted tumor progression in 4 lesions for which Ktransratio predicted radiation injury (MRP and PET were performed on the same day for 2 lesions; MRP preceded PET for 2 lesions by 2 and 7 days). PET-CT correctly predicted radiation injury in 3 lesions for which Ktransratio predicted tumor progression (MRP and PET were performed on the same day for 2 lesions; PET preceded MRP for 1 lesion by 10 days).

Correlation of Combinations of DCE-MRI and PET-CT Metrics with Clinical Outcomes

We next explored combinations of DCE-MRI and PET-CT metrics to determine whether they would further improve prediction of clinical outcomes. When using the optimal thresholds of Vpratio ≥ 2.1 and Ktransratio ≥ 3.6, the combination of these 2 metrics had sensitivity of 79% for accurate diagnosis of progression, and specificity of 94% for accurate diagnosis of radiation injury. Compared with using Vpratio alone, combining Vpratio and Ktransratio improved accuracy in predicting radiation injury but not progression. When Vpratio ≥ 2.1 and SUVratio ≥ 1.2 were combined, the rate of correct classification of progression was 66% and the rate of correct classification of radiation injury was 88%, also improving the predictive value for radiation injury compared with any individual metric.

Subgroup Analyses

The metastasis subgroup (n = 26) consisted of more patients with diagnoses of radiation injury (n = 15, 68%) than of progression (n = 11, 42%). In this subgroup, Vpratio remained a significant predictor of radiation injury (P = .001), as did Ktransratio (P = .005) and SUVratio (P = .004), while the other metrics were not (P ≥ .18). When a Vpratio threshold of ≥2.6 was used to declare progression, sensitivity was 91% and specificity was 80%. The use of a Ktransratio threshold of ≥4.1 to declare progression yielded sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 67%. Vpratio and Ktransratio measurements were not significantly different between the progressive metastases (n = 11) and the progressive gliomas (n = 27) (P = .062). The use of an SUVratio threshold of ≥1.4 to declare progression yielded sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 80%.

Discussion

DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT are frequently utilized for the purpose of distinguishing between tumor progression and radiation injury in the brain.19,20,28–30 However, there is no clear consensus on which modality is more accurate or whether the 2 modalities provide complementary information. In this prospective study, we systematically analyzed the accuracy of DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT in differentiating progression and radiation injury in patients who developed indeterminate enhancing lesions after RT for gliomas or brain metastases. To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective series providing a direct comparison of the effectiveness of DCE-MRI and FDG PET-CT in the same set of patients. We found that DCE-MRI and PET-CT were both useful in distinguishing between progression and radiation injury, although DCE-MRI (AUC = 0.76–0.87) slightly outperformed PET-CT (AUC = 0.75). The predictive values of these techniques increased when they were used in combination.

Compared with conventional MRI alone, DCE-MRI can improve diagnosis, predict prognosis, and inform treatment decisions in patients with brain tumors.31,32 While the literature has demonstrated the benefits of using DCE-MRI in distinguishing progression and radiation injury, the majority of the studies were retrospective and included small numbers of patients. Metrics such as increased cerebral blood volume ratio,20,33 decreased percentage of signal-intensity recovery,20,30 and increased relative peak height20 have all been associated with progression in both gliomas and brain metastases. A recent study of 33 patients treated with RT for gliomas found that increased Ktrans and Ve correlated with progression.34 We did not find Ve to be a significant predictor (P = .17), possibly because of heterogeneous contributions to Ve from additional physiologic factors such as capillary bed perfusion and permeability.35 However, we did find that Vpratio, which provides estimates of vascular perfusion and microvascular density, and Ktransratio, which provides estimates of vascular leakiness related to altered permeability, permeability surface area product, and flow, were significant predictors. Specifically, Vpratio was the most robust predictor of progression (AUC = 0.87; 92% sensitivity using a cutoff of 2.1) of the 5 DCE-MRI metrics tested. When Vpratio and Ktransratio were combined, accuracy in predicting radiation injury improved to 94% from 77% for Vpratio only and 71% for Ktransratio only. The increased accuracy reflects the complementary roles of Vpratio and Ktransratio, which investigate different pathophysiologic properties and have been recognized as independent imaging biomarkers.36,37 We did not detect a difference in Vpratio, Ktransratio, or SUVratio between the progressive metastasis subgroup and the progressive glioma subgroup (P = .062). We also found similar optimal thresholds for the whole group and the metastasis subgroup; for simplicity, we therefore suggest that the proposed whole-group thresholds are sufficient for routine clinical use regardless of the underlying tumor pathology.

Using FDG PET-CT, we determined that SUVratio was effective in distinguishing between progression and radiation injury but trended toward lower predictive value compared with Vpratio (AUC = 0.75 vs 0.87, P = .061). Prior studies have also shown increased SUVratio in progression30,38 without finding PET-CT to be superior to DCE-MRI. The combination of Vpratio with SUVratio did not yield higher predictive value than Vpratio alone. The SUVratio threshold of ≥1.2 demonstrated higher specificity for progression than either Vpratio or Ktransratio alone, but its specificity was lower than that of the combination of Vpratio and Ktransratio (82% vs 94%). DCE-MRI also performed better than PET-CT when the results of DCE-MRI and PET-CT were discordant. This has implications for clinical care, as DCE-MRI alone may be sufficient for the evaluation of indeterminate lesions in many patients. Furthermore, DCE-MRI may offer the added benefits of being less expensive and less time-consuming than PET-CT, as at some institutions (including ours) patients with brain tumors are already routinely followed with MRI.

Our study had several potential limitations. First, we included a heterogeneous group of patients who had both primary and metastatic tumors. It is possible that optimal cutoff values for distinguishing radiation injury from progression differ between patients with gliomas and patients with metastases, although our results and other studies have shown that they have similar values.39,40 The inclusion of both primary and metastatic tumors reflects actual practice with heterogeneous patient populations and therefore broadens the potential applicability of our results. Nevertheless, an ongoing subsequent study with a larger patient cohort is under way at our institution, which will allow for more detailed analyses of patients with primary versus metastatic disease. Second, not all patients underwent surgery for their enlarging brain lesions; however, the clinical and radiological criteria we used to determine follow-up outcomes were familiar and commonly applied in research trials and in daily practice. Third, a disproportionate number of the patients with primary tumors were determined to have progression. This may reflect our relatively conservative definitions of radiation injury as complete absence of any tumor at histopathology and no new treatment for a minimum of 6 months at follow-up. Fourth, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses for the glioma cohort due to the unequal numbers of patients in the progression and radiation injury groups. Nevertheless, a subgroup analysis including only the patients treated for brain metastases showed that Vpratio remained the most effective imaging metric in distinguishing progression and radiation injury. Fifth, the DCE acquisition time may not have been sufficiently long enough to allow for precise measurement of Kep and Ve. We typically observe a new slightly elevated baseline toward the end of the signal-intensity time curve, suggesting that the equilibrium phase has been reached and washout has been achieved. Although extending the time of DCE acquisition would help confirm that equilibrium has been reached, it has been suggested that proper modeling of the tracer kinetics is sufficient to correctly estimate the constancy of the parameters over time.41–43

In conclusion, we found that the DCE-MRI metrics Vpratio and Ktransratio, as well as the SUVratio derived from FDG PET-CT, were useful in distinguishing progression from radiation injury. Of all the individual metrics assessed, Vpratio was the most robust predictor of progression, and the combination of Vpratio and Ktransratio was able to predict radiation injury with 94% accuracy. Our results should be validated in a larger cohort that allows for separate analyses for patients with gliomas and patients with metastases.

Funding

R.J.Y.'s research is partly supported by the Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. K.M.W. and Z.Z.'s research is partly supported by NIH grant P30 CA008748.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the expert editorial advice given by Ada Muellner, Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. . Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP et al. . Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF et al. . Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U et al. . Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952-26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dropcho EJ. Neurotoxicity of radiation therapy. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(1):217–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruben JD, Dally M, Bailey M et al. . Cerebral radiation necrosis: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors with emphasis on radiation parameters and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(2):499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minniti G, Clarke E, Lanzetta G et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: analysis of outcome and risk of brain radionecrosis. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan C, Yang TJ, Hilden P et al. . A phase 2 trial of stereotactic radiosurgery boost after surgical resection for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(1):130–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Wit MC, de Bruin HG, Eijkenboom W et al. . Immediate post-radiotherapy changes in malignant glioma can mimic tumor progression. Neurology. 2004;63(3):535–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullins ME, Barest GD, Schaefer PW et al. . Radiation necrosis versus glioma recurrence: conventional MR imaging clues to diagnosis. .AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(8):1967–1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field KM, Simes J, Nowak AK et al. . Randomized phase 2 study of carboplatin and bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;1711:1504–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahmathulla G, Marko NF, Weil RJ. Cerebral radiation necrosis: a review of the pathobiology, diagnosis and management considerations. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(4):485–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field M, Witham TF, Flickinger JC et al. . Comprehensive assessment of hemorrhage risks and outcomes after stereotactic brain biopsy. J Neurosurg. 2001;94(4):545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreth FW, Muacevic A, Medele R et al. . The risk of haemorrhage after image guided stereotactic biopsy of intra-axial brain tumours—a prospective study. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2001;143(6):539–545; discussion 545–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gijtenbeek JM, Wesseling P, Maass C et al. . Three-dimensional reconstruction of tumor microvasculature: simultaneous visualization of multiple components in paraffin-embedded tissue. Angiogenesis. 2005;8(4):297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remler MP, Marcussen WH, Tiller-Borsich J. The late effects of radiation on the blood brain barrier. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12(11):1965–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiryo T, Lopes MB, Kassell NF et al. . Radiosurgery-induced microvascular alterations precede necrosis of the brain neuropil. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(2):409–414; discussion 414–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha S, Johnson G, Wadghiri YZ et al. . Dynamic, contrast-enhanced perfusion MRI in mouse gliomas: correlation with histopathology. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(5):848–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barajas RF Jr., Chang JS, Segal MR et al. . Differentiation of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme from radiation necrosis after external beam radiation therapy with dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;253(2):486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barajas RF, Chang JS, Sneed PK et al. . Distinguishing recurrent intra-axial metastatic tumor from radiation necrosis following gamma knife radiosurgery using dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. .AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(2):367–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao ST, Suh JH, Raja S et al. . The sensitivity and specificity of FDG PET in distinguishing recurrent brain tumor from radionecrosis in patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Cancer. 2001;96(3):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murase K. Efficient method for calculating kinetic parameters using T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(4):858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wetzel SG, Cha S, Johnson G et al. . Relative cerebral blood volume measurements in intracranial mass lesions: interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility study. Radiology. 2002;224(3):797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young R, Babb J, Law M et al. . Comparison of region-of-interest analysis with three different histogram analysis methods in the determination of perfusion metrics in patients with brain gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(4):1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha S, Knopp EA, Johnson G et al. . Intracranial mass lesions: dynamic contrast-enhanced susceptibility-weighted echo-planar perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;223(1):11–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA et al. . Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1963–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young RJ, Gupta A, Shah AD et al. . Potential utility of conventional MRI signs in diagnosing pseudoprogression in glioblastoma. Neurology. 2011;76(22):1918–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu LS, Baxter LC, Smith KA et al. . Relative cerebral blood volume values to differentiate high-grade glioma recurrence from posttreatment radiation effect: direct correlation between image-guided tissue histopathology and localized dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging measurements. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ericson K, Kihlstrom L, Mogard J et al. . Positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with stereotactically irradiated brain metastases. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1996;66(suppl 1):214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatzoglou V, Ulaner GA, Zhang Z et al. . Comparison of the effectiveness of MRI perfusion and fluorine-18 FDG PET-CT for differentiating radiation injury from viable brain tumor: a preliminary retrospective analysis with pathologic correlation in all patients. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(3):451–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law M. Advanced imaging techniques in brain tumors. Cancer Imaging. 2009;9(Special issue A):S4–S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Law M, Young R, Babb J et al. . Comparing perfusion metrics obtained from a single compartment versus pharmacokinetic modeling methods using dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging with glioma grade. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(9):1975–1982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y, Horiguchi S et al. . Perfusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging to distinguish the recurrence of metastatic brain tumors from radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(1):81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yun TJ, Park CK, Kim TM et al. . Glioblastoma treated with concurrent radiation therapy and temozolomide chemotherapy: differentiation of true progression from pseudoprogression with quantitative dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2015;2743:830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HS, Kim AH, Ahn SS et al. . Glioma grading capability: comparisons among parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and ADC value on DWI. Korean J Radiol. 2013;14(3):487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alcaide-Leon P, Pareto D, Martinez-Saez E et al. . Pixel-by-pixel comparison of volume transfer constant and estimates of cerebral blood volume from dynamic contrast-enhanced and dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging in high-grade gliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(5):871–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha S, Yang L, Johnson G et al. . Comparison of microvascular permeability measurements, K(trans), determined with conventional steady-state T1-weighted and first-pass T2*-weighted MR imaging methods in gliomas and meningiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(2):409–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YH, Oh SW, Lim YJ et al. . Differentiating radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence in high-grade gliomas: assessing the efficacy of 18F-FDG PET, 11C-methionine PET and perfusion MRI. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(9):758–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cha S, Lupo JM, Chen MH et al. . Differentiation of glioblastoma multiforme and single brain metastasis by peak height and percentage of signal intensity recovery derived from dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(6):1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangla R, Kolar B, Zhu T et al. . Percentage signal recovery derived from MR dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging Is useful to differentiate common enhancing malignant lesions of the brain. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(6):1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta RK, Awasthi R, Garg RK et al. . T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced MR evaluation of different stages of neurocysticercosis and its relationship with serum MMP-9 expression. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(5):997–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alcaide-Leon P, Rovira A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR: importance of reaching the washout phase. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(5):E58–E59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rathore RK, Gupta RK. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR: importance of reaching the washout phase. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(5):E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]