Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most predominant solid carcinomas in Western countries. However, there is conflicting information on the effects of soy isoflavone on CRC risk. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk in humans using PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases. A total of 17 epidemiologic studies, which consisted of thirteen case-control and four prospective cohort studies, met the inclusion criteria. Our research findings revealed that soy isoflavone consumption reduced CRC risk (relative risk, RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.72–0.85; I2 = 34.1%, P = 0.024). Based on subgroup analyses, a significant protective effect was observed with soy foods/products (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.69–0.89), in Asian populations (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.72–0.87), and in case-control studies (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.68–0.84). Therefore, soy isoflavone consumption was significantly associated with a reduced risk of CRC risk, particularly with soy foods/products, in Asian populations, and in case-control studies. However, due to the limited number of studies, other factors may affect this association.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most prevalent cancer worldwide and one of the most common solid carcinomas in Western countries1. Therefore, primary CRC prevention efforts should be explored. Based on recent estimates, the CRC incidence rate is higher in developed nations than in developing countries2. Lifestyle habits and diet may play key roles in the etiology of CRC3,4. Soy isoflavones, which are phytoestrogens, have a protective effect against cancer formation and susceptibility to radiotherapy; other anti-cancer phytochemicals in soy beans include phenolic acids, plant sterol, and protease inhibitors5,6,7,8,9,10.

The association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk has been evaluated11,12. A meta-analysis of four cohort studies and seven case-control studies failed to detect any association between soy consumption and risk of CRC, colon cancer, or rectal cancer12. Due to a low statistical power and small sample size of each individual study, the results were not consistent with the findings of several epidemiological studies13,14,15,16. Therefore, the objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk. Our meta-analysis included case-control and cohort studies13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 and subgroup analyses by geographic area, study type, anatomical subsite, gender, and soy food type.

Methods

Search strategy

We performed a literature search of relevant studies published through November, 2015 using PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Embase (http://www.embase.com/), Web of Science (http://wokinfo.com/), and Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/). The search strategy included terms for outcome (colorectal neoplasm, colorectal cancer, colon cancer, and rectal cancer) and exposure (soy, soy foods/products, isoflavones, soybeans, flavonoid, tofu, soy protein, miso, genistein, phytoestrogen, and natto). We designed, implemented, and reported our meta-analysis based on epidemiological study guidelines30. In addition, we reviewed the reference lists from all relevant articles to identify additional studies. A search for unpublished literature was not performed.

Study selection

The study inclusion criteria were the following, (i) studies written in English with case-control or cohort design; (ii) original human clinical trials that evaluated the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk; and (iii) use of risk point estimates, e.g., odd ratio (OR), relative risk (RR), or hazard ratio (HR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Data extraction

The extracted data were the first author’s name, year of publication, cancer type, population and country, total number of cases, dietary assessment method, estimates of soy isoflavone intake, and RRs or ORs with 95% CIs. Five publications reported separate RRs for soy foods and soy isoflavones, five publications reported separate RRs for male and female participants, and two publications reported separate RRs for colon and rectal cancers. In these cases, RRs were extracted individually.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk using the reported RRs. Soy isoflavones were defined as soy foods, soy products, isoflavones, tofu, soy milk, miso, natto, genistein, daidzein, and flavonols. When adjusted and crude RRs were provided, the most adjusted RRs were extracted.

We used HR and OR to evaluate CRC risk. HR and OR were considered to be approximations to RR, because CRC is a rare outcome in humans. Pooled RRs and 95% CIs were estimated on the basis of the most adjusted RRs or ORs for the highest versus lowest soy isoflavone intake.

We used I2 and Q statistics to assess possible homogeneity of RRs across studies, which is a quantitative measure of inconsistency among studies31. Pooled ORs and 95% CIs were calculated using a random effects model32. To estimate cancer site-specific and ethnicity-specific effects, subgroup analyses were performed by geographic area, study type, anatomical subsite, gender, and soy isoflavone type. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of a single study on the overall risk estimate. This allowed us to estimate whether the results could have been significantly affected by a single study.

Data analyses were performed with STATA version 13.0. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. Egger’s and Begger’s regression models were used to evaluate potential publication bias31. All reported P values were from two-sided statistical tests.

Results

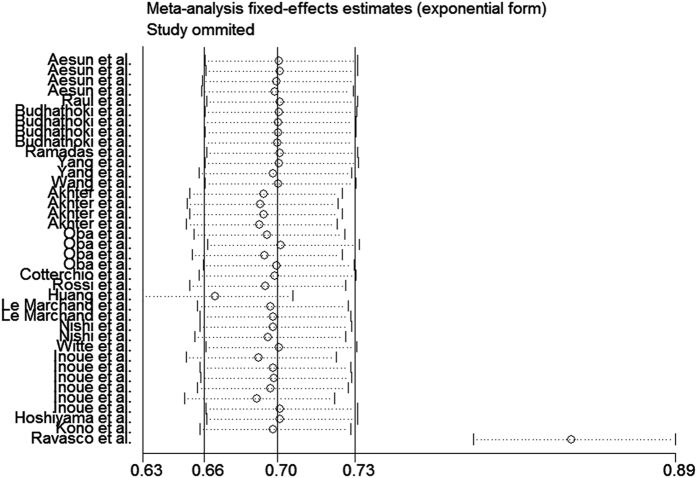

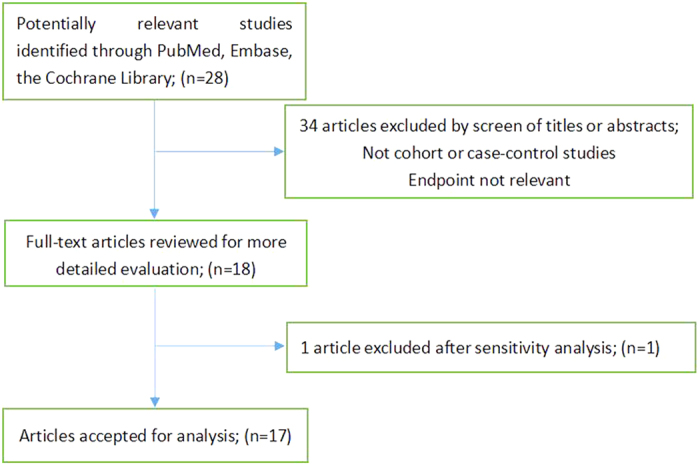

The study selection process is graphically described in Fig. 1. Twenty studies met our inclusion criteria. Two studies were subsequently excluded, because one was an ecological study and the other study failed to report RR or 95% CI. After conducting a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the Ravasco et al. study33 (Fig. 2). Finally, 17 studies13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1). The most predominant dietary assessment method used in these studies was the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).

Figure 1. Search strategy and selection of studies.

Figure 2. Sensitivity analysis of soy isoflavone consumption and risk of colorectal cancer excluding the study of Ravasco et al.33.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Year | Cancer type | Population and country | No. of cases | Dietary assessment | Exposure | Consumption comparison | Adjustment RR (95% CI) | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aesun et al. | 2015 | CRC | 2,669 Korea | 901 | SQFFQ | Soy products | Highest versus lowest | Colorectal 0.67 (0.49–0.92), M 0.62 (0.39–1.00), F | Age, education, alcohol consumption, and regular physical activity |

| Isoflavones | Highest versus lowest | Colorectal 0.71 (0.52–0.97), M 0.78 (0.50–1.23), F | |||||||

| Raul et al. | 2013 | CRC | 825 Spain | 424 | FFQ | Isoflavones | Highest versus lowest | Colorectal 0.59 (0.35–0.99) | Sex, age, BMI, energy intake, alcohol and fiber intake |

| Budhathoki et al. | 2010 | CRC | 1,631 Japan | 816 | FFQ | Soy foods | 37.2 (23.0–54.9) (mg/d) versus 35.5 (22.3–52.3) (mg/d) | Colorectal 0.65 (0.41–1.03), M 0.60 (0.29–1.25), F | Age, resident area, parental colorectal cancer, smoking, alcohol consumption, BMI, job, leisure-time physical activity, and energy-adjusted intakes of calcium and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| Isoflavones | 0.68 (0.42–1.10), M 0.68 (0.33–1.40), F | ||||||||

| Ramadas et al. | 2009 | CRC | 108 Malaysia | 59 | FFQ | Soy products | <3 times/week versus ≥3 times/week | Colorectal 0.38 (0.15–0.98) | Age, ethnicity, gender, physical activity, height, BMI, waist circumference, energy intake, current alcohol consumption and smoking habits |

| Yang et al. | 2009 | CRC | 68,412 women China | 321 | FFQ | Soy foods | ≤12.8 versus >21.0 g/d | Colorectal 0.67 (0.49–0.90), F | Birth calendar year, education, BMI, household income, physical activity, colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives, menopausal status, and dietary intakes of total calories, red meat, total fruit and vegetables, non-soy fiber, non-soy calcium, and non-soy folic acid |

| Isoflavones | ≤15.1 versus >48.9 mg/d | 0.76 (0.56–1.01), F | |||||||

| Wang et al. | 2009 | CRC | 38,408 women US | 301 | SFFQ | Soy foods (Tofu) | <1 time/month versus ≥1 time/week | Colorectal 0.54 (0.20–1.46), F | Age, race, total energy intake, and randomized treatment assignment, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, postmenopausal status, hormone replacement therapy use, multivitamin intake, family history of cancer in a parent or sibling, and intake of fruit and vegetables, fiber, folate, and saturated fat |

| Akhter et al. | 2008 | CRC | 38,408women Japan | 886 | FFQ | Soy foods | ≤35.4 versus >169.9 g/d, M ≤35.6 versus >170.3 g/d, F | Colorectal 0.89 (0.68–1.17), M 1.04 (0.76–1.42), F | Age, public health center, area, history of diabetes mellitus, BMI, leisure time physical activity, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, energy-intake, menopausal status, use of female hormones |

| Isoflavones (Genistein) | ≤9.1 versus >50.4 mg/d, M | 0.89 (0.67–1.17), M 1.07 (0.78–1.47), F | |||||||

| Oba et al. | 2007 | Colon cancer | 30,221 Japan | 213 | FFQ | Soy products | ≤49.22 versus >141.09 g/d, M | Colon 1.24 (0.77–2.00), M 0.56 (0.34–0.92), F | Age, physical activity, cigarette smoking status, height, BMI, alcohol and coffee consumption, hormone replacement therapy (for women) |

| Isoflavones | 22.45 versus 59.58 mg/d, M | 1.47 (0.90–2.40), M 0.73 (0.44–1.18), F | |||||||

| Cotterchio et al. | 2006 | CRC | 1,890 Canada | 1,095 | FFQ | Isoflavones | 0 versus >1.097 mg/d | 0.71 (0.58–0.86) | Age, sex, and total energy intake |

| Rossi et al. | 2006 | CRC | 4,154 Italy | 1,953 | FFQ | Isoflavones | ≤14.4 versus >33.9 μg/d | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) | Age, sex, study center, family history of colorectal cancer, education, alcohol consumption, BMI, occupational physical activity, and energy intake |

| Huang et al. | 2004 | CRC | 50,706 Japan | 1,352 | FFQ | Bean curd | <3 versus ≥ 3 times/week | Colorectal 1.11 (0.92–1.33) | Age and sex |

| Nishi et al. | 1997 | Colon Cancer Rectal cancer | 660 Japan | 330 | FFQ | Soy products (Tofu) | <3 versus ≥ 3 times/week | Colon 0.79 (0.55–1.13) Rectum 1.02 (0.67–1.53) | Age, sex and registered residence |

| Le Marchan et al. | 1997 | CRC | 1,192 US | 1,192 | FFQ | Tofu | 0 versus ≥25 g/d | Colorectal 1.0 (0.6–1.6), M 0.9 (0.5–1.5), F | Nutrient intakes for calories, age, family history of colorectal cancer, alcoholic drink, cigarette smoking, Quetelet index previous five year, total calories, egg intake, lifetime recreational activity (in hours), and calcium intake |

| Witte et al. | 1996 | CRC | 488 US | 488 | FFQ | Tofu or Soy beans | None versus ≥1 serving/week | Colorectal 0.55 (0.27–1.11) | Race; body mass index); vigorous leisure time activity; smoking; dietary fiber, folate, beta-carotene, and vitamin C |

| Inoue et al. | 1995 | Rectal Cancer | 31,782 Japan | 432 | FFQ | Bean curd | ≤3 versus >3 times/week | Proximal colon 0.9 (0.5–1.6), M 1.3 (0.7–2.4), F Distal colon 1.7 (1.0–2.6), M 0.6 (0.4–1.0), F Rectum 1.2 (0.8–1.7), M 0.9 (0.6–1.5), F | Age |

| Hoshiyama et al. | 1993 | Colon Cancer | 653 Japan | 181 | FFQ | Soy bean | ≤4 versus ≥8 times/week | Colon 0.6 (0.3–1.3) Rectum 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | Sex, age for colon cancer, selected food items; sex and age for rectal cancer |

| Kono et al. | 1993 | Colon Cancer | 1,557 Japan | 187 | FFQ | Soy paste soup | <1 versus ≥2 bowls/d | Colon 0.87 (0.55–1.37) | Smoking, alcohol consumption, rank and BMI |

BMI: body mass index, CI: confidence interval, FFQ: food frequency questionnaire, RR: relative risk, SQFFQ: semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire; F: female, M: male, Null: not provided.

Thirteen studies assessed the association between soy product consumption and CRC risk, while nine studies evaluated the association between isoflavone consumption and CRC risk. Among them, six studies separately presented findings for men and women, and two studies separately reported results for risk of rectal and colon cancers. Twelve studies were conducted in Asia and five in non-Asia countries (Table 2). Data from both men and women were individually extracted. Different soy food types were evaluated in these studies; some studies assessed more than one type of soy food. Therefore, we used the risk estimate that was the most representative of overall soy consumption and the soy food item that was the most commonly consumed. In descending order, the most common soy food or products were tofu (bean curd), soy beans, soy milk, and miso soup (soy paste soup).

Table 2. Stratified analysis of colorectal cancer in relation to soy isoflavone consumption according to study characteristics.

| Group | No. of studies | RR (95% CI) | P heterogeneity | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soy types and colorectal cancer | ||||

| Soy foods/products | 14 | 0.79 (0.69–0.89) | 0.006 | 46.2% |

| Isoflavones | 8 | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | 0.559 | 0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6 | 0.86 (0.73–0.99) | 0.085 | 38.4% |

| Female | 8 | 0.74 (0.66–0.83) | 0.493 | 0 |

| anatomical subsite | ||||

| Colorectal | 12 | 0.77 (0.70–0.84) | 0.092 | 28.6% |

| Colon | 4 | 0.85 (0.64–1.05) | 0.082 | 44.6% |

| Rectum | 3 | 0.87 (0.52–1.22) | 0.05 | 61.7% |

| Study types | ||||

| Cohort | 4 | 0.83 (0.71–0.95) | 0.118 | 35.1% |

| Case-control | 13 | 0.76 (0.68–0.84) | 0.045 | 34.4% |

| Geographic area | ||||

| Asia | 12 | 0.79 (0.72–0.87) | 0.01 | 41.1% |

| Non-Asia | 5 | 0.74 (0.64–0.83) | 0.722 | 0 |

No, number; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

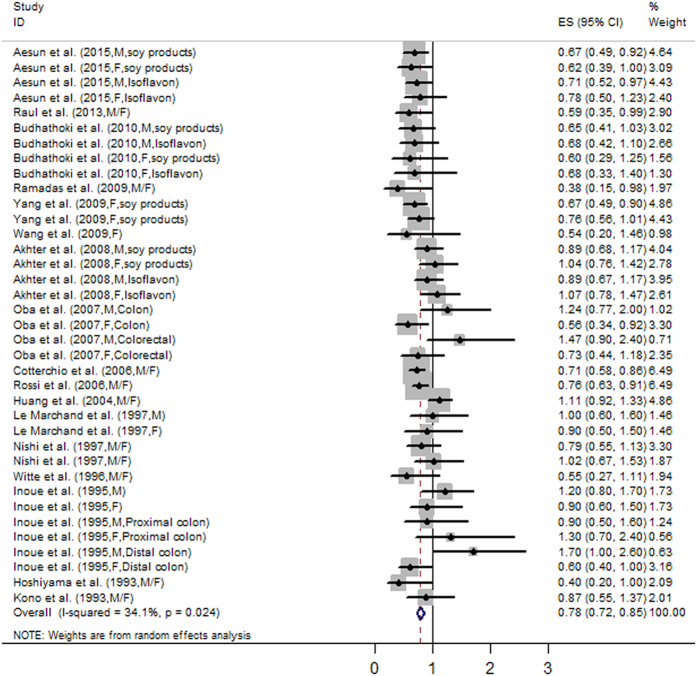

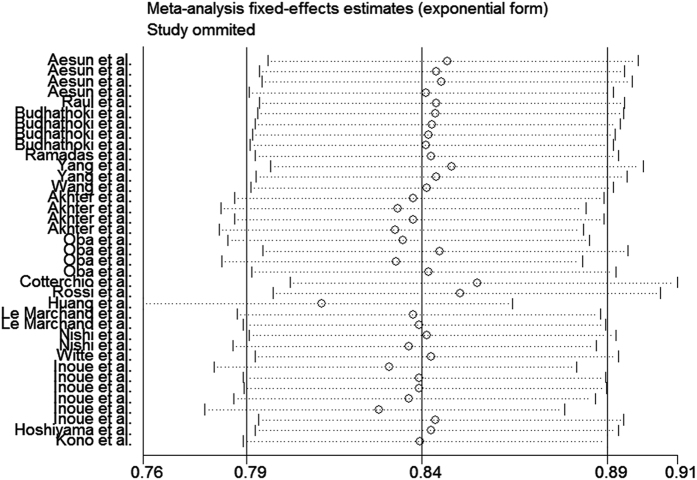

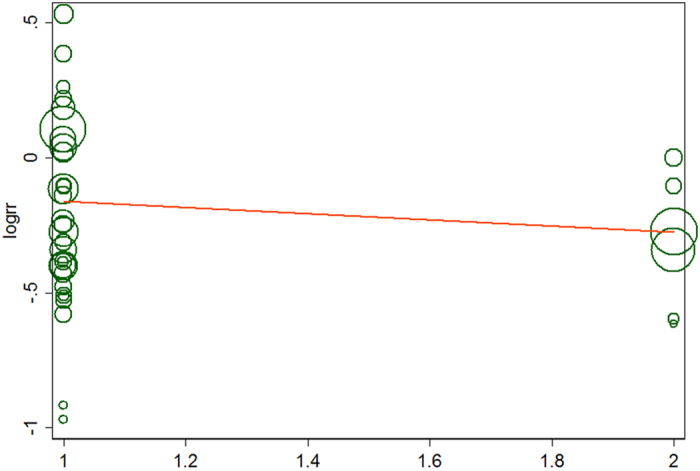

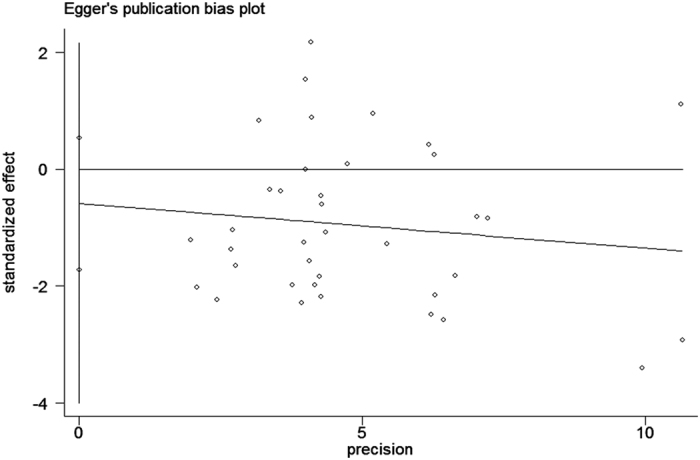

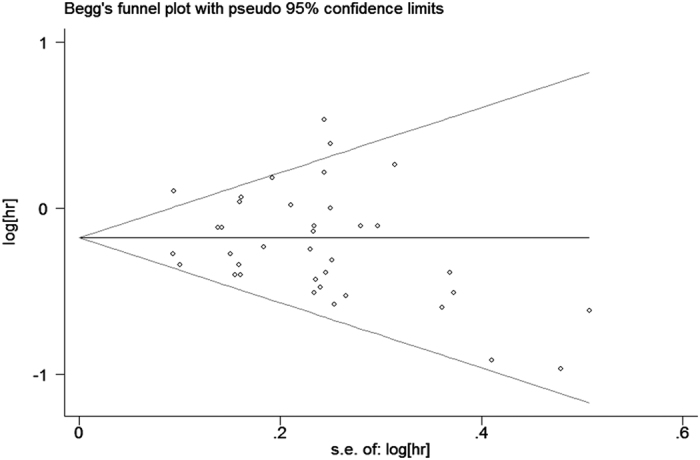

The analysis of the 17 studies yielded a combined risk estimate of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.72–0.82; P = 0.024) with a heterogeneity value (I2) of 34.1% (Fig. 3). However, the results from the 17 studies were inconsistent. Nine studies reported that soy isoflavone intake was associated with a significant reduction in CRC risk, whereas other studies reported no association. Six studies reported that soy isoflavone intake was associated with a significant reduction in CRC risk in both men and women, three studies reported a significant reduction in CRC risk only in women, and other studies reported no association in women or men. We conducted a sensitivity analysis (Fig. 4) and meta regulation test (Fig. 5). The sensitivity analysis revealed that the publication dates were similar. The geographical area was associated with ~44.3% heterogeneity reduction across the studies. No publication bias was detected (Figs 6 and 7) based on Egger’s and Begger’s regression models32.

Figure 3. Forest plot of studies evaluating the association between soy isoflavone consumption and risk of colorectal cancer.

Figure 4. Sensitivity analysis of soy isoflavone consumption and risk of colorectal cancer.

Figure 5. Meta regulation of isoflavone consumption and risk of colorectal cancer.

Figure 6. Egger’s funnel plot assessing publication bias among the studies.

Figure 7. Begger’s funnel plot assessing publication bias among the studies.

Because there were differences in study types (cohort or case-control), study populations (Asian or non-Asian), anatomical subsite (colorectal, colon, or rectum), gender (female versus male), and soy isoflavone type (soy foods/products or soy isoflavones) among the studies, we further conducted subgroup analyses to determine the effect of these factors in our analyses (Table 2). We obtained a statistically significant protective effect of soy foods/products (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.72–0.84), in Asian populations (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.73–0.85), and with case-control studies (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.70–0.81).

Discussion

We analyzed 17 epidemiological studies that assessed the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk in humans. The findings revealed that the consumption of soy isoflavones was associated with a 23% reduction in CRC risk. CRC is caused by environmental (e.g., diet and lifestyle) and genetic factors34. When stratified by geographical area, a significant protective effect of soy isoflavone consumption was observed in Asian populations, which are likely to be attributed to their lifestyle habits and overall health. Ecological and immigration studies have shown that differences in CRC risk among populations are largely attributed to environmental factors, such as eating habits. Asian populations have higher intakes of soy isoflavones than Western populations35. The consumption of Western diets, which are high in fat and calories, is associated with an increased incidence in CRC. Dietary fat increases the secretion of bile acids, which directly damage the intestinal mucosa, stimulate epithelial hyperplasia, and increase CRC risk36. On the other hand, the frequency of physical activity is lower in Asian populations than in American or European populations. Regular physical activity is a protective factor against CRC, because it reduces random motions of the intestine and stimulates bowel movements. Additionally, physical activity promotes the secretion of prostaglandins, which stimulate peristalsis and cleansing and reduce the contact time between the intestinal mucosa and carcinogens37,38. When stratified by study design, a significant protective effect of soy isoflavone intake was observed with case-control studies, which could be attributed to higher recall rates and greater selection bias in these types of studies. When stratified by soy foods/products and soy isoflavones, a significant protective effect was observed with soy foods/products, probably due to a limited number of studies focused on soy isoflavones.

Epidemiological and animal studies have found that the consumption of dietary soy decreases the incidence of certain tumors, including those of the colon and rectum39,40,41,42,43. The three main soy isoflavone aglycones are genistein, daidzein, and glycitein43. The mechanism by which soy protects against the development of CRC remains unclear. It has been reported that in CRC, there is a reduced expression of estrogen receptor-β (ER-β) expression44. Dietary isoflavones increase ER-β expression, but reduce ER-α expression in the colon of female rats45. In CRC patients, ER gene expression is either diminished or absent46.

Our meta-analysis had some limitations. First, only studies written in English were included. Second, most studies used FFQs as the main dietary assessment method. Recall bias may have affected the results. Additionally, it was challenging to predict the effect of misclassification of case-control studies on the results. Third, certain confounding factors were not adjusted in the evaluated studies, e.g., family history of CRC, smoking, and alcohol consumption, which are important risk factors of CRC47,48,49. Fourth, we failed to evaluate a dose-response relationship between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk.

There was heterogeneity across the studies in terms of soy isoflavone consumption, which is not surprising considering the differences in the study designs, soy types, and gender. Additionally, differences in geographic area may have contributed to the heterogeneity results; most of the studies were conducted in Asia, where the consumption of soy is high. Moreover, while some studies were adjusted for age, gender, and family history of CRC in the calculation of risk estimates, not all parameters were considered. The measurement units varied among the studies. Sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially omitting one single study to assess the effect of each study on the overall results (Fig. 2). The Egger’s funnel plot revealed a P value > 0.05; the shape of the Begger’s funnel plot seemed symmetrical. There was no significant evidence for publication bias in our meta-analysis (P > 0.05).

In summary, our meta-analysis provided an updated and comprehensive evaluation of the association between soy isoflavone consumption and CRC risk, with an RR value of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.72–0.82, P = 0.024) and an I2 value of 34.1%. A statistically significant protective effect was observed with soy foods/products (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.72–0.84), in Asian populations (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.73–0.85), and with case-control study designs (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.70–0.81). Soy isoflavones play an important protective role in the pathogenesis of CRC, by a mechanism that remains to be elucidated. More cohort and intervention studies are required.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yu, Y. et al. Soy isoflavone consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 25939; doi: 10.1038/srep25939 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-2013-81372022), and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2011B061300031).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.Y., X.J. and H.L. wrote the main manuscript text and X.Z. and D.W. prepared Figs 1–7. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Y.Y., X.J. and H.L. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Stintzing S. Management of colorectal cancer. F1000Prime Rep 6, 108 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A. et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61, 69–90 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle V. C. Nutrition and colorectal cancer risk: a literature review. Gastroenterol Nurs 30, 178–182 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas A. J. & Thompson P. A. Diet and nutrient factors in colorectal cancer risk. Nutr Clin Prac 27, 613–623 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudenz M., Roth K. & Gerhauser C. Impact of soy isoflavones on the epigenome in cancer prevention. Nutrients 6, 4218–4272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A. H., Lee E. & Vigen C. Soy isoflavones and breast cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 33, 102–106 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres S., Abraham K., Appel K. E. & Lampen A. Risks and benefits of dietary isoflavones for cancer. Crit Rev Toxicol 41, 463–506 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman G. G. & Singh-Gupta V. Soy isoflavones sensitize cancer cells to radiotherapy. Free Radic Biol Med 51, 289–298 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina M. & Bennink M. Soyfoods, isoflavones and risk of colonic cancer: a review of the in vitro and in vivo data. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab 12, 707–728 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell K. D. & Cole S. J. Variations in isoflavone levels in soy foods and soy protein isolates and issues related to isoflavone databases and food labeling. J Agric Food Chem 51, 4146–4155 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann A. J., Kasenda B. & Briel M. Meta-analyses: what they can and cannot do. Swiss Med Wkly 142, w13518 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L. et al. Soy Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Humans: A Meta-Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19, 148–158 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadas A. & Kandiah M. Food Intake and Colorectal Adenomas: A Case-Control Studyin Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10, 925–932 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhathoki S. et al. Soy food and isoflavone intake andcolorectal cancer risk:The Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. Scand J Gastroenterol 46, 165–172 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Ros R. et al. Association between habitual dietary flavonoid and lignan intakeand colorectal cancer in a Spanish case-control study(the Bellvitge Colorectal Cancer Study). Cancer Causes Control 24, 549–557 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin A. et al. Isoflavone and Soyfood Intake andColorectal Cancer Risk: A Case-Control Studyin Korea. PLos One 10, e0143228 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. et al. Prospective cohort study of soy food intake and colorectal cancer risk in women. Am J Clin Nutr 89, 577–583 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba S. et al. Soy product consumption and the risk of colon cancer: a prospective study in Takayama, Japan. Nutr Cancer 57, 151–157 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Dietary intake of selected flavonols, flavones, and flavonoid-rich foods and risk of cancer in middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr 89, 905–912 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter M. et al. Dietary soy and isoflavone intake and risk of colorectal cancer in the Japan public health center-based prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17, 2128–2135 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. E. et al. Comparison of lifestyle risk factors by family history for gastric, breast, lung and colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 5, 419–427 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Marchand L. et al. Dietary fiber and colorectal cancer risk. Epidemiology 8, 658–665 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M., Yoshida K., Hirata K. & Miyake H. Eating habits and colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 4, 995–998 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte J. S. et al. Relation of vegetable, fruit, and grain consumption to colorectal adenomatous polyps. Am J Epidemiol 144, 1015–1025 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M. et al. Subsite-specific risk factors for colorectal cancer: a hospital-based case-control study in Japan. Cancer Causes Control 6, 14–22 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiyama Y., Sekine T. & Sasaba T. A case-control study of colorectal cancer and its relation to diet, cigarettes, and alcohol consumption in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med 171, 153–165 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono S., Imanishi K., Shinchi K. & Yanai F. Relationship of diet to small and large adenomas of the sigmoid colon. Jpn J Cancer Res 84, 13–19 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CotterchioM. et al. Dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with reduced colorectal cancer risk. J Nutr 136, 3046–3053 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M. et al. Flavonoids and colorectal cancer in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15, 1555–1558 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J. & Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C. B. & Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50, 1088–1101 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials 45, 139–145 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravasco P., Monteiro-Grillo I., Marqués Vidal P. & Camilo M. E. Nutritional risks and colorectal cancer in a Portuguese population. Nutr Hosp 20, 165–172 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tárraga López P. J., Albero J. S. & Rodríguez-Montes J. A. Primary and Secondary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol 7, 33–46 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S. et al. Soy, isoflavones, and breast cancer risk in Japan. J Natl Cancer Inst 95, 906–913 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein C. et al. A bile acid-induced apoptosis assay for colon cancer risk and associated quality control studies. Cancer Res 59, 2353–2357 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmen F. A. & Simmen R. C. The maternal womb: a novel target for cancer prevention in the era of the obesity pandemic? Eur JCancerPrev 20, 539–548 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson S. C., Rutegård J., Bergkvist L. & Wolk A. Physical activity, obesity, and risk of colon and rectal cancer in a cohort of Swedish men. Eur J Cancer 42, 2590–2597 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papenburg R., Bounous G., Fleiszer D. & Gold P. Dietary milk proteins inhibit the development of dimethylhydrazine-induced malignancy. Tumour Biol 11, 129–136 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyomura K. & Kono S. Soybeans, soy foods, isoflavones and risk of colorectal cancer: a review of experimental and epidemiological data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 3, 125–132 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector D., Anthony M., Alexander D. & Arab L. Soy consumption and colorectal cancer. Nutr Cancer 47, 1–12 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkak R., Korourian S., Ronis M. J., Johnston J. M. & Badger T. M. Soy protein isolate consumption protects against azoxymethane-inducedcolon tumors in male rats. Cancer Lett 166, 27–32 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiagarajan D. G., Bennink M. R., Bourquin L. D. & Kavas F. A. Prevention of precancerous colonic lesions in rats by soy flakes, soy flour, genistein, and calcium. Am J Clin Nutr 68, 1394S–1399S (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielecki A., Roberts J., Mehta R. & Raju J. Estrogen receptor-β mediates the inhibition of DLD-1 human colon adenocarcinoma cells by soy isoflavones. Nutr Cancer 63, 139–150 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer F., Johnson I. T., Doleman J. F. & Lund E. K. A comparison of the effects of soya isoflavonoids and fish oil on cell proliferation, apoptosis and the expression of oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in the mammary gland and colon of the rat. Br J Nutr 102, 29–36 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa J. P. et al. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet 7, 536–540 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperiale T. F. & Ransohoff D. F. Risk for colorectal cancer in persons with a family history of adenomatous polyps: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 156, 703–709 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustgi A. K. The genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Genes Dev 21, 2525–2538 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin A. et al. Associations of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption with advanced or multiple colorectal adenoma risks: a colonoscopy-based case-control study in Korea. Am J Epidemiol 174, 552–562 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]