Abstract

The mammalian cutaneous low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) are a diverse set of primary somatosensory neurons that function to sense external mechanical force. Generally, LTMRs are composed of Aβ-LTMRs, Aδ-LTMRs, and C-LTMRs, which have distinct molecular, physiological, anatomical, and functional features. The specification and wiring of each type of mammalian cutaneous LTMRs is established during development by the interplay of transcription factors with trophic factor signalling. In this review, we summarize the cohort of extrinsic and intrinsic factors generating the complex mammalian cutaneous LTMR circuits that mediate our tactile sensations and behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

The sensation of mechanical force from the external world is an integral part of our everyday experience. It helps us move through space, allows us to identify objects and textures, and facilitates social behaviors such as shaking hands, hugging, and kissing. Mechanical force causes movement of the skin or hair, which in turn activates mechanosensitive neuronal fibers (mechanoreceptors) innervating the skin or hair follicles. While the high-threshold mechanoreceptors (i.e., the nociceptive neurons that only respond to intense mechanical stimuli) mediate mechanical pain, the cutaneous low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) mediate innocuous touch.1 Mammalian cutaneous LTMRs are a subpopulation of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons. Their cell bodies lie in the DRGs or TGs and elaborate a single axonal process that bifurcates to give rise to a peripheral branch (innervating the skin/hair) and a central branch (innervating the spinal cord or brainstem).

Classically, the mammalian cutaneous LTMRs have been categorized based on their conduction velocity, cell body and axon diameter, and myelination thickness. Aβ-LTMRs are fast conducting (ranging from 30 to 100 m/second, averaging ~40–60 m/ second), have large soma size/axon diameters, and are highly myelinated. Aδ-LTMRs conduct more slowly (ranging from 4 to 30 m/second, averaging ~20 m/second), have intermediate cell body/axon diameters, and are thinly myelinated. C-LTMRs are slow conducting (<2.5 m/second, averaging ~0.6–1 m/second), have small cell body/axon diameters, and are unmyelinated.1 Each LTMR can be further classified based on its response to sustained mechanical stimuli. ‘Rapidly adapting’ (RA) mechanoreceptors fire at the onset, and sometimes at the offset, of a stimulus, but only fire sparingly or not at all during the stimulus. ‘Slowly adapting’ (SA) mechanoreceptors not only respond with a burst of firing at the stimulus onset, but sustain firing throughout the stimulus. In between these response types, ‘intermediate adapting’ LTMRs show a burst of firing at the stimulus onset followed by maintained firing throughout the stimulus at a rate lower than SA-LTMRs.1 As described above and further below, Aβ-, Aδ-, and C-LTMRs display great diversity with regard to their physiological, molecular, anatomical, and functional properties. In this review, we will discuss recent progress in understanding the specific molecular mechanisms that control the development of each type of mammalian cutaneous LTMR.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF MAMMALIAN DRG NEURONS

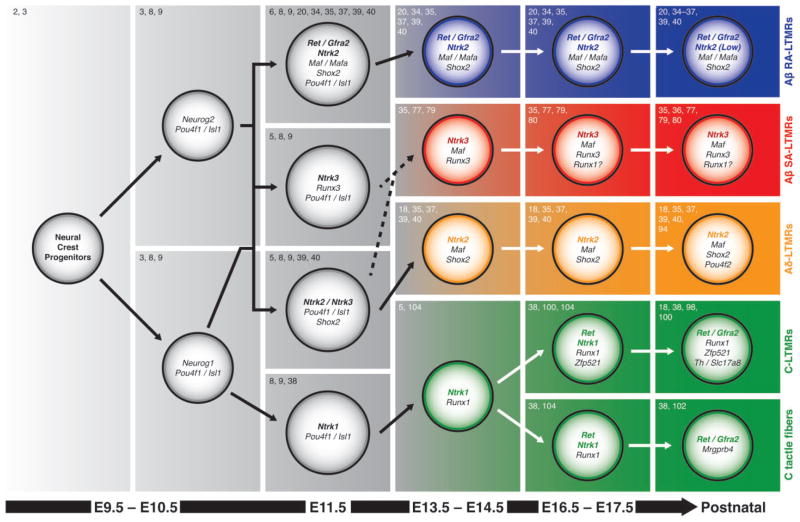

All DRG neurons are derived from neural crest cell progenitors that delaminate from the neural tube between embryonic Day 9 (E9) and E10.5 in mice and migrate ventrolaterally.2 These cells coalesce into ganglia beginning around E9.52,3 and then give rise to postmitotic neurons. Those exiting the cell cycle differentiate quickly, with the last DRG neurons exiting the cell cycle around E13.5.4 DRG neurogenesis and early differentiation depend on the expression of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) neurogenin transcription factors (Figure 1). An initial wave of neurogenin 2 (Neurog2) expression generates a group of NTRK3+, NTRK2+, or RET+ large-diameter neurons that will become the majority (~70%) of Aβ/δ-LTMRs and proprioceptors (somatosensory neurons sensing muscle length and tension) (Box 1). A second wave of neurogenin 1 (Neurog1) expression generates the remaining ~30% of the Aβ/δ-LTMRs/proprioceptors as well as NTRK1+ small diameter neurons that will become C-LTMRs, nociceptors, and pruriceptors (somatosensory neurons mediating itch sensation).3,5

FIGURE 1.

Illustration showing specification of different subtypes of mammalian cutaneous low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs). The major known genes that specify each subtype at different stages are shown here. The final column shows main molecular markers to identify each subtype of LTMR in adult mice. Instances where the developmental lineage or gene expression for a given population is unclear are indicated with dotted lines or question marks. Reference citations are shown at the upper left-hand corner of each panel.

BOX 1. NEUROTROPHIC FACTOR RECEPTORS AND THEIR LIGANDS.

NTRK1 (formerly known as TRKA) is the receptor for nerve growth factor (NGF). NTRK2 (formerly known as TRKB) is the receptor for brain-derived growth factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 5 (NTF5, formerly known as neurotrophin 4). NTRK3 (formerly known as TRKC) is the receptor for neurotrophin 3 (NTF3). NGF, BDNF, NTF5, and NTF3 also bind to the low-affinity neurotrophin receptor NGFR (formerly known as p75). RET and GFRAs are the receptor and coreceptors, respectively, for the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family of ligands.6

Neurog1 and Neurog2 promote the expression of other bHLH transcription factors including Neurod1 and Neurod4 (formerly known as Math3),7 which are characteristic of early neuronal differentiation. Shortly before these neurons exit the cell cycle, they start to express the homeodomain transcription factors Pou4f1 (formerly known as Brn3a) and Isl18,9 (Figure 1). Pou4f1 and Isl1 each regulate a diverse set of genes with a significant amount of overlap. Together, Pou4f1 and Isl1 facilitate the exit out of the neurogenic phase by repressing genes important for early development (including Neurog1, Neurod1, and Neurod4) and by promoting the expression of genes involved in sensory neuron differentiation. These include other transcription factors, neurotrophic receptors, axon growth/targeting genes, and neuronal function genes.10–14 DRGs lacking both Pou4f1 and Isl1 fail to express Ntrk1, Ntrk2, Ntrk3, and Ret, demonstrating that specification of all DRG sensory neurons is dependent on Pou4f1/Isl1 activity.14 In addition, deletion of either Pou4f1 or Isl1 results in major sensory axon growth defects and failure to innervate the skin due to the misregulation of axon growth/targeting genes in these mutants.11,15 Moreover, expression of Pou4f1 with either Neurog1 or Neurog2, or expression of Neurog1 with Isl2 and other transcription factors, can convert human or mouse fibroblasts into some types of somatosensory neurons in vitro.16,17 These results support the critical roles of the Neurog1, Neurog2, Pou4f1, and Isl1 in the specification of mammalian somatosensory neurons.

DEVELOPMENT OF Aβ-LTMRs

The Aβ-LTMRs constitute ~10% of all DRG neurons.18,19 They are derived from the early NTRK2+/ NTRK3+/RET+ large-diameter neurons generated by the Neurog2 and Neurog1 waves.3 While there is a high degree of overlap between RET and NTRK2 and between NTRK2 and NTRK3 at E11.5, they become increasingly segregated by E14.55 (see Figure 1), and these neurons then begin to express the neurofilament heavy chain protein NEFH.20 Since Aβ-LTMRs can be further subdivided based on their adaptation properties (RA or SA), we will discuss their developmental mechanisms separately.

Aβ RA-LTMRs

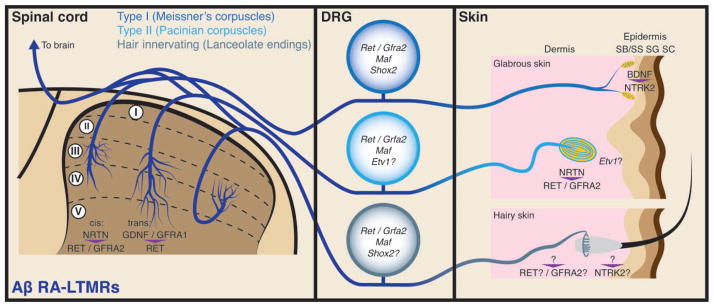

Aβ RA-LTMRs include Meissner’s corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles, and Lanceolate Endings (Figure 2). Meissner’s corpuscles, or RAI-LTMRs, are located within the dermal papillae of glabrous skin. They feature disc-like lamellar stacks of Schwann-like cells innervated by Aβ fibers (Figure 2). Multiple Aβ fibers can innervate a single corpuscle, and individual Aβ fibers can innervate 1 or 2 corpuscles.1,21,22 Meissner’s corpuscles have small receptive fields, show RA-type response properties, and respond best to low frequency (~30–40 Hz) vibration.1,23 They likely act as velocity detectors of skin deformation,1 and the activation of Meissner’s corpuscle fibers in human subjects causes a ‘fluttering’ sensation.23 Pacinian corpuscles, or RAII-LTMRs, are oval-shaped end organs composed of an outer core of lamellar perineural cells and an inner core of Schwann cells (Figure 2). Their location varies between species; while both rodents and primates have Pacinian corpuscles in their interosseous membranes, joints, tendons, muscles, and other deep tissues, primates additionally have Pacinian corpuscles in the subcutaneous fat pads of their fingers, palms, and soles.24 Each corpuscle is innervated by a single Aβ axon.25 Pacinian corpuscles have large, poorly defined receptive fields and respond best to high-frequency vibration (250–300 Hz) of the skin.1,23 Lanceolate endings surround whisker hair follicles along with guard and awl (but not zigzag) follicles in mouse back hairy skin. They form a palisade of endings surrounding the follicle, with each ending composed of a flattened stack of Schwann cells innervated by an Aβ axonal branch18 (Figure 2). The palisades surrounding one hair follicle can be innervated by multiple individual axonal fibers and individual axons can innervate multiple hair follicles.26 In addition, Aβ lanceolate endings can coinnervate hair follicles along with lanceolate endings from Aδ- and/or C-LTMRs.18 Aβ lanceolate endings most likely function as detectors of hair movement velocity.1

FIGURE 2.

Illustration showing molecular mechanisms that control peripheral and central terminal development of Aβ rapidly adapting-low-threshold mechanoreceptors (RA-LTMRs). Genes that are important for Aβ RA-LTMR development are indicated in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cell body. Signalling molecules that direct terminal development are indicated in the spinal cord and skin. In the epidermis, SB/SS = stratum basalis/stratum spinosum, SG = stratum granulosum, SC = stratum corneum.

Centrally, the Aβ RA-LTMR central axon enters the spinal cord and bifurcates to send branches extending in both the rostral and caudal direction in the spinal cord dorsal column. Almost all ascending axons of Aβ RA-LTMR reach the dorsal column nuclei (DCN).27,28 Several interstitial collaterals from each rostral/caudal axon enter the dorsal horn gray matter and synapse with spinal cord interneurons (Figure 2). Each Aβ RA-LTMR subtype arborizes differently in the dorsal horn. Meissner’s corpuscle afferents arborize at the medial aspect of layers III-V.27,29,30 The dorsal horn collateral arborization of Pacinian corpuscle neurons features a dorsal zone of innervation focused in layer III and a small ventral zone of innervation focused in layer V.27,31,32 The dorsal horn terminals of Aβ hair afferents (lanceolate endings) form distinctive ‘flame-shaped’ arbors.27,33

Aβ RA-LTMR Specification

Most Aβ RA-LTMRs can be identified by their expression of Ret early in development (E11.5-E13.5, the ‘early RET+’ DRG neurons), a subset of which also coexpress Ntrk25,20,34 (Figure 1). Postnatally, large diameter RET+ neurons will express Ret only, Ret and Ntrk2, or Ret and Ntrk3. Since Ntrk2GFP knock-in mice preferentially label Aδ- rather than Aβ-LTMRs in adults,18 Ntrk2 expression in Aβ RA-LTMRs must be low in adulthood. Consistent with this, a recent study used single-cell RNA sequencing to perform unbiased clustering of adult mouse DRG neurons and identified three clusters of putative large diameter LTMRs: one Ntrk2low/calbindin 1+ population (potential Aβ RA-LTMRs35), one Ntrk2high population (potential Aδ-LTMRs18), and one Ntrk3 positive population (potential Aβ SA-LTMRs, see below).36

Aβ RA-LTMRs begin to express the transcription factor Maf (formerly known as c-Maf) around the same time that they express Ret, followed by the expression of the transcription factor Mafa and the RET coreceptor Gfra2.20,34,37 Maf is required for the maintenance of Ret, Gfra2, and Mafa expression in Aβ RA-LTMRs (although Ntrk2 expression is independent of Maf).36,37 In addition, sensory neuron conditional deletion of Maf using Isl1Cre results in RA-LTMRs that are hyperexcitable and display a slower adaptation property. These changes can be partially explained by the downregulation of the potassium channel KCNQ4 in these mutants.35 Mafa null mice also show a partial reduction in Ret and Gfra2 expression, indicating a role for Mafa in maintaining expression of these genes. Mafa and Maf function redundantly to some extent in Aβ RA-LTMRs.34 Moreover, RET signaling plays a critical role in Aβ RA-LTMR specification in addition to its role in promoting survival.20,38 Neural crest conditional Ret mutants (generated using Wnt1Cre) have a deficit in the maintenance of Gfra2 and Mafa expression, and mice null for the RET-GFRA2 ligand Nrtn also show a deficit in the maintenance of Gfra2 expression.20,34 The expression of Maf is unchanged in Ret mutants.35

The development of NTRK3+ and NTRK2+ mechanoreceptors is coordinated by the transcription factors Runx3 and Shox2. Runx3 is highly expressed at E11.5 by NTRK3+ proprioceptor precursors, acting to promote the expression of Ntrk3 and to repress the expression of Ntrk2 and Shox2.5,39 A low level of Runx3 is seen at E11.5 in NTRK2+ neurons, which subsequently maintain Ntrk2 and down-regulate Ntrk35 (see Figure 1). While almost all DRG neurons express Shox2 at E11.5-E12.5, its expression is only maintained in subsets of Ntrk2 and Ret expressing neurons. Since neural crest specific deletion of Shox2 (using Wnt1Cre) causes a reduction in Ntrk2 expression while ectopic expression of Shox2 increases Ntrk2 expression, Shox2 must promote the expression of Ntrk2.39,40 In addition, Shox2 appears to play a role in repressing Ntrk3 in the RET+/ NTRK2+ cells, although ectopic Shox2 does not downregulate the level of Ntrk3 in RET negative cells.39,40

Aβ RA-LTMR Central Terminal Development

The development of Aβ RA-LTMR interstitial collaterals highly depends on RET signaling (Figure 2). Neural crest conditional deletion of Ret greatly reduces the dorsal horn collateral projections of Aβ RA-LTMRs.20,41 RET is unusual in comparison to other receptor tyrosine kinases in that it does not bind directly to its ligands. Instead, the ligand must first bind to a GPI-anchored GDNF family receptor ∝ (GFRA) coreceptor which then leads to the recruitment, dimerization, and activation of RET.42 In vitro studies have demonstrated that RET can be activated by a coreceptor expressed in the same cell as RET (cis-signaling) or by a soluble coreceptor (trans-signaling).43,44 For the developing Aβ RA-LTMRs, Gfra2 is coexpressed with Ret in the early RET+ DRG neurons while Gfra1 is expressed in the dorsal spinal cord, dorsal root entry zone, and neighboring DRG neurons. This expression pattern suggests that both cis- and trans-RET activation could occur to promote the growth of Aβ RA-LTMR central projections.20,45,46 Indeed, recent work from our lab demonstrated that activation of RET either in cis by GFRA2 or in trans by GFRA1 can support the growth of Aβ RA-LTMR central terminals, which provides the first in vivo example of trans-RET signaling.47

In contrast to the requirement of RET signaling in Aβ RA-LTMR central projection development, neural crest specific deletion of Ntrk2 has no obvious effect on the spinal cord terminals of Aβ RA-LTMRs.20 Since the loss of Ntrk2, but not Ret, severely affects Meissner’s corpuscle development in the periphery (see below),20,48 NTRK2 and RET signaling likely play distinct roles in peripheral versus central terminal development of Aβ RA-LTMRs.

Both Maf sensory neuron conditional knockout and Shox2 neural crest conditional knockout mice were reported to have reduced Aβ-LTMR central innervation in spinal cord dorsal horn layers III-V.35,40 Since Maf sensory neuron conditional knockout DRGs show a downregulation of Ret and Gfra2,35,37 the Maf phenotype could be caused either by downregulation of RET signaling or by RET-independent mechanisms. In addition, given that neural crest conditional deletion of Ntrk2 does not affect Aβ-LTMR central terminals,20 the reduction of Aβ-LTMR central innervation in Shox2 neural crest conditional mutants is likely through an Ntrk2-independent mechanism.

Aβ RA-LTMR Peripheral Terminal Development

In mice and rats, Aβ-LTMR axons destined to innervate Meissner’s corpuscles arrive at the dermal papillae shortly after birth and initiate the formation of the corpuscle. Local Schwann cells differentiate to form corpuscle lamellar cells around 1 week after birth, and corpuscle maturation continues until about postnatal Day 20 (P20).25,49 Early postnatal nerve crush experiments demonstrate that corpuscle formation is dependent on axon innervation.49 BDNF–NTRK2 signaling is essential for this process (Figure 2); Meissner’s corpuscles do not form in mutant mice that have a nonfunctional Ntrk2 kinase domain or in Bdnf null mice, although they do form in Ntf5 null mice.48,50 Since Ntrk2 and Bdnf knockout mice both have a ~30% reduction in DRG cell number, the lack of Meissner’s corpuscles in these mice could simply be caused by cell death of Meissner corpuscle neurons.51,52 However, other lines of evidence have also suggested that the role of NTRK2 signaling in Meissner corpuscle formation could be independent of DRG neuron survival. Similar to observations in Ntrk2 null mice, neural crest conditional knockout of Ntrk2 prevents corpuscle formation. However, myelinated axons are still present in the dermal papillae in these mice around P14.20 In addition, immunostaining of Meissner’s corpuscles localizes NTRK2 to the lamellar cells but not the axon.53 Furthermore, overexpression of either Bdnf or Ntf5 in the skin increases the size of Meissner’s corpuscles but does not increase DRG cell number.54,55 These results suggest that Meissner’s corpuscle formation might require local NTRK2 signaling in the lamellar cells.

Since Shox2 promotes Ntrk2 in DRG neurons, Shox2 mutant mice have a severe reduction in Meissner’s corpuscles as well.39 Sensory neuron conditional deletion of Maf also causes a severe reduction in the number of Meissner’s corpuscles.35 Since Ntrk2 levels are unchanged in these mice, this effect must be independent of NTRK2 signaling. While the Meissner’s corpuscle-innervating neurons express Ret, it does not appear to play a major role in Meissner’s corpuscle formation. These corpuscles are still present after deletion of Ret from the neural crest lineage, although they may appear underdeveloped and disorganized.20

Similar to Meissner’s corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles fail to form upon neonatal denervation.49 Like all Aβ RA-LTMRs, the neurons that innervate Pacinian corpuscles arise from the early RET+ DRG population.20 In contrast to other classes of Aβ RA-LTMRs, the development of Pacinian corpuscles is completely dependent on RET signaling (Figure 2). No Pacinian corpuscles are formed in neural crest conditional Ret mutant, in Gfra2 null, or in Nrtn null mice.20 It remains unclear why different classes of RA-LTMRs display differential requirements for RET signaling. Other neurotrophic factor signaling pathways may also contribute to Pacinian corpuscle formation, though it remains to be determined whether they function in primary afferents or the accessory cells.56

Maf sensory neuron conditional knockout mice have a reduced number of Pacinian corpuscles, and the remaining corpuscles are smaller and morphologically abnormal.35,37 As in Meissner’s corpuscles, this phenotype could be caused by a downregulation of RET signaling in these mutants, although RET-independent mechanisms are also possible. Humans with Maf missense mutations have difficulty sensing vibration at frequencies detected by Pacinian corpuscles.35 Interestingly, these patients show no deficit in sensing vibrations at lower frequencies that are normally detected by Meissner’s corpuscles. Another transcription factor, the ETS transcription factor Etv1, is expressed in both DRG neurons and the Schwann cells that make up the inner core of the Pacinian corpuscle. Etv1 mutant mice lack Pacinian corpuscles.57 At present, it is unclear in which cell types Etv1 functions to control Pacinian corpuscle formation.

The molecular mechanisms directing the formation of Aβ-LTMR lanceolate endings are much less clear. This is because the analysis of mutant phenotypes for lanceolate endings is more difficult due to the presence of three types of lanceolate endings (Aβ, Aδ, and C) intermingled around individual hair follicles.18 Additionally, a high degree of variability exists in both the number of endings surrounding one follicle and the number of follicles innervated by one Aβ-, Aδ-, or C-LTMR axon,26 further complicating analysis of mutant phenotypes. For example, although neural crest conditional deletion of either Ret or Ntrk2 severely affects Meissner’s and Pacinian corpuscle development, Aβ lanceolate endings still appear to be present in the hairy skin of these mice.20,51 The lack of clear phenotypes could reflect technical difficulty in quantifying this specific phenotype and/or suggest potential functional redundancy between RET and NTRK2 signaling. Shox2 neural crest conditional mutant mice show poorly developed lanceolate endings at P6, but it is difficult to determine which neuronal type is affected.39 Maf sensory neuron conditional knockout mice show a severe deficit in NEFH+/NTRK2low (most likely Aβ RA-LTMR) lanceolate endings, suggesting that Maf plays an important role in the development of all types of Aβ RA-LTMRs.35

Aβ SA-LTMRs

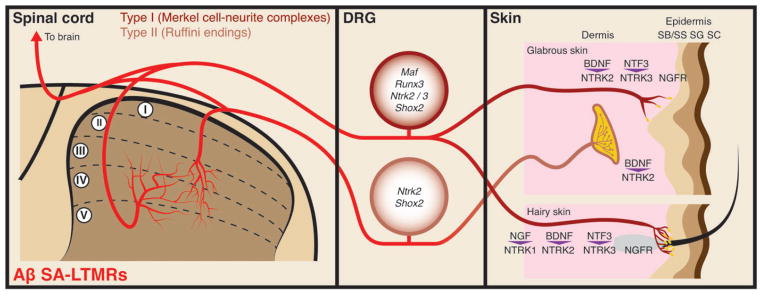

The SA Aβ-LTMRs are Merkel cell-neurite complexes and Ruffini endings (Figure 3). Merkel cell-neurite complexes, or SAI-LTMRs, are SA-type mechanoreceptors with very small, restricted receptive fields that respond to very light indentation of the skin.58 Based on their response properties and small receptive fields, they are well adapted for high-resolution discrimination of shape and texture.59

FIGURE 3.

Illustration showing molecular mechanisms that control peripheral terminal development of Aβ slowly adapting-low-threshold mechanoreceptors (SA-LTMRs). Genes that are important for Aβ SA-LTMR development are indicated in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cell body. Signalling molecules that direct terminal development are indicated in the skin.

The Merkel cell-neurite complexes are found in both glabrous and hairy skin. Each complex, known as a ‘touch spot’ in glabrous skin and a ‘touch dome’ in hairy skin, features an Aβ neuronal fiber associated with a cluster of ~5–150 Merkel cells in the basal epidermis1,25 (Figure 3). Touch domes in the hairy skin are associated with hair follicles in rodents but are present in the interfollicular skin in other mammalian species.25 Interestingly, the primary afferents that innervate Merkel cells may be different between hairy and glabrous skin. In the glabrous skin, Merkel cells are innervated exclusively by large diameter NTRK3+/NEFH+ Aβ fibers. In contrast, neonatal touch dome Merkel cells in the mouse hairy skin are innervated by both NTRK3+/NEFH+ Aβ and RET+/NTRK1+ fibers.60 Most of these RET+ neurites are missing in Ntrk1 null mice, indicating that they are developmentally distinct from the large diameter early RET+ Aβ RA-LTMRs discussed above. The physiological significance for the dual innervation of neonatal touch dome Merkel cells by both large-diameter and small-diameter fibers is unclear. Notably, some postnatal large-diameter RET+ DRG neurons are also NTRK3+,34 which could give rise to the Merkel cell-innervating RET+ neurites that remain in Ntrk1 null mice. The exact developmental history of this RET+/NTRK3+ population has yet to be determined (see Figure 1). Centrally, the dorsal horn collaterals of Merkel cell-innervating Aβ SA- LTMRs dive into layers IV-V and then make a medial C-shaped turn before innervating layers III-V (Figure 3).27

The nature of the functional relationship between Merkel cells and their innervating axons has long been an area of contention. Recent work suggests a two-receptor-site model in which both the Merkel cell and the innervating neurite are mechanosensitive.61–64 This idea is supported by the following evidence: (1) Merkel cells and neurites make connections that look very similar to synapses in ultrastructural studies,65,66 (2) Merkel cells have the machinery for neurotransmitter release,67 (3) blocking glutamatergic transmission from Merkel cells reduces SAI responses,68 (4) genetically ablating Merkel cells eliminates SAI responses,69 (5) Merkel cells express the mechanosensory channel Piezo2 and they display both Piezo2-dependent mechanically activated currents and calcium action potentials (APs),62,63 (6) both Merkel cell specific ablation of Piezo2 and inhibition of Merkel cell APs greatly diminishes the sustained phase of the SAI response,62,63 while the dynamic phase is still recorded when Merkel cells are silenced, when Piezo2 is knocked down or ablated from Merkel cells, or when Merkel cell APs are inhibited,61–63 and (7) neurites innervating Merkel cells express Piezo2 and conditional ablation of Piezo2 from both the neurite and the Merkel cells greatly reduces both dynamic phase and static phase firing of Aβ SAI fibers.64 Therefore, Merkel cells and their innervating afferents work together to encode different aspects of the SAI response.

Ruffini endings, or SAII-LTMRs, have SA response properties, large receptive fields, and primarily respond to stretching of the skin.1,70,71 Early work identified the end organs of SAII-LTMRs as elongated corpuscles of perineural cells and Schwann cells innervated by single Aβ axons72 (the Ruffini ending, Figure 3). Later work found that, although mouse, raccoon, monkey, and human skin feature numerous SAII units based on physiological recordings, Ruffini endings are difficult to identify histologically in these skin samples.22,71,73–76 Therefore, the anatomical structure of SAII-LTMR fibers in the skin is currently obscure. The central terminals of SAII-LTMRs in the dorsal horn travel into layer III, where they split into at least two branches that then project ventrally to innervate layers III-VI27 (Figure 3).

Aβ SA-LTMR Specification and Central Terminal Development

In contrast to the Aβ RA-LTMRs, which can be exclusively labeled based on their expression of Ret early in development,20 Aβ SA-LTMRs currently have no exclusive molecular markers. Merkel cell-innervating Aβ SA-LTMR fibers are NTRK3+, SLC17A7+ (formerly known as VGLUT1), and NEFH+.60,77 However, proprioceptors are also NTRK3+,78 whereas SLC17A7 and NEFH mark all proprioceptors and Aβ LTMRs. Ntrk2, Ntrk3, and Runx3 mutants all have deficits in Aβ SA-LTMR peripheral development (see below).51,77,79 However, whether NTRK3+ Aβ SA-LTMRs are derived from the NTRK3+/RUNX3+ lineage, the NTRK3+/NTRK2+ lineage, or both, is currently unclear (Figure 1). As mentioned above, recent single-cell RNA-seq clustering of adult DRG neurons identified one cluster of putative LTMRs defined by high expression of Ntrk3 and no expression of the proprioceptor marker parvalbumin (potential Aβ SA-LTMRs).36 In addition, a small population of putative mechanosensory DRG neurons coexpresses Runx1 and Runx3 into adulthood, and subsets of these neurons express Ntrk2 and Ntrk3.80 Given that Runx3 is important for Aβ SA-LTMR development, some of these neurons may be Aβ SA-LTMRs as well.

Shox2 may function in Aβ SA-LTMRs to promote Ntrk2 expression, as Shox2 neural crest conditional mutant mice have deficient Merkel cell touch dome innervation.40 Furthermore, physiological recordings from Maf sensory neuron conditional knockout mice found that SAI units have higher mechanical thresholds, indicating that Maf directs some aspects of SAI-LTMR specification. Although central innervation deficits of Aβ sensory neurons are seen in Shox2 neural crest conditional and Maf sensory neuron conditional knockouts,35,40 it remains to be determined whether these effects are specific for the central projections of Aβ RA-LTMRs, Aβ SA-LTMRs, or both populations.

Aβ SA-LTMR Peripheral Terminal Development

Unlike the end organs of Meissner’s and Pacinian corpuscles, Merkel cell clusters are found in the skin prior to sensory innervation.25 The embryological origin of Merkel cells is debatable since they share characteristics with both epidermal and neural cells. Chick-quail chimera experiments and genetic labeling of neural crest cells using Wnt1Cre mice suggest that Merkel cells arise from the neural crest.81,82 However, some recent findings have also supported an epidermal origin for Merkel cells. For example, the transcription factor Atoh1 is required for Merkel cell development, and conditional deletion of Atoh1 from epidermal cells, but not the neural crest, prevented Merkel cell development.83

Several classes of neurotrophins function in Merkel cell-neurite complex development84 (Figure 3). NGF/NTRK1 signaling is important for a subpopulation of Merkel cell-neurite complexes. Ntrk1 kinase domain knockout mice have reduced numbers of Merkel cells and innervating neurites around the whisker pad hair follicle.77 The remaining Merkel cell complexes are maintained into adulthood, suggesting that this subset of complexes is NTRK1-independent. Ngf knockout mice have a similar, but less severe, phenotype.85 Similarly, NTRK1 is required for some innervation of touch dome Merkel cells in the mouse body. In Ntrk1 nulls, the proportion of Merkel cells innervated by NTRK1+ fibers is greatly reduced while the number of Merkel cells innervated by NTRK3+ fibers is unchanged.60 These results are consistent with the fact that some hairy skin Merkel cell-innervating fibers are NTRK1+/RET+, though they do not express NEFH and may not be SAI-LTMRs. RET signaling plays a relatively minor role in Merkel cell-neurite complex development.20,34,60

NTRK2 signaling also plays a role in Merkel cell-neurite complex development. In Ntrk2 knockout mice, there is a large reduction in the number of Merkel cells in glabrous and hairy skin.51 Overexpression of Bdnf in the skin increases the number of Merkel cells present in glabrous, but not hairy, skin.54 BDNF/NTRK2 signaling also modulates the physiological response of Merkel cell-neurite complexes. Bdnf heterozygous and null mice have SAI units with increased mechanical thresholds, although the number and morphology of Merkel cells in touch domes appear unaffected. Injection of BDNF into the skin rescues this deficit in Bdnf heterozygotes.86 Shox2 neural crest conditional knockout mice have a reduction in Merkel cell innervation, possibly because of the reduced Ntrk2 expression in these mice.39

Among all neurotrophins, NTF3/NTRK3 signaling plays perhaps the most critical role in the development of Merkel cell-neurite complexes. Both Merkel cells and a majority of the innervating neurites express Ntrk3.60,77,79 In Ntrk3 kinase domain knockout mice, fewer Merkel cells are present at birth and the number of Merkel cells continues to decrease during the first two postnatal weeks, indicating a continuous dependency of Merkel cells on NTRK3 signaling during postnatal development.77 Ntf3 knockout mice show an even more severe deficit in Merkel cell complex formation at birth.87 In Ntrk3 null mice, no Merkel cells or innervating fibers are present at birth, suggesting that NTRK3 may have kinase-independent roles in the development and survival of Merkel cells.77,85 Runx3 mutants have defective Merkel cell innervation of whisker follicles, possibly due to the reduced Ntrk3 expression in trigeminal neurons.79

Finally, NGFR signaling is also important for Merkel cell development. In Ngfr nulls, the number and appearance of Merkel cells are normal at birth but begin to decrease in number starting around 2 weeks of age, with very few remaining in adulthood.85,88

Knowledge of the development of Ruffini endings is very limited compared to that for the other classes of Aβ-LTMRs, mostly due to difficulty in reliably identifying these endings. Ruffini-like endings appear to be dependent on NTRK2 signaling (Figure 3). Periodontal and whisker hair Ruffini endings are absent in Ntrk2 knockout mice and are either greatly reduced or are morphologically deficient in Bdnf knockouts.89,90 Loss of Ntf5 leads to morphological deficits in periodontal Ruffini endings but has no effect on whisker hair Ruffini endings.91 Interestingly, the number of whisker hair associated Ruffini endings increases in Ntf3 knockout mice.85

DEVELOPMENT OF Aδ-LTMRs

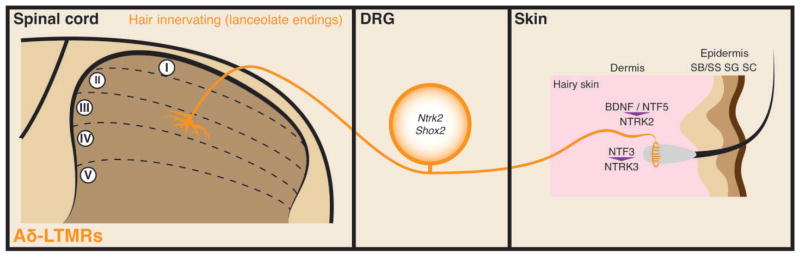

Aδ-LTMRs, also known as D hair cells, have RA responses and are highly sensitive to mechanical force.1,18 They represent ~7% of adult DRG neurons.18 Aδ-LTMRs form palisades of lanceolate endings around zigzag and awl/auchenne (but not guard) hair follicles in the back hairy skin and have large receptive fields18 (Figure 4). Centrally, Aδ-LTMRs enter the spinal cord and send a single projection that runs rostrally for a few segments before turning ventrally to innervate the dorsal gray matter. They arborize in layer III of the dorsal horn, dorsal to the Aβ-LTMRs18,92 (Figure 4). Owing to their high sensitivity, these cells are tuned to respond to very gentle touch of hairy skin or to gentle displacement of hair follicles.1

FIGURE 4.

Illustration showing molecular mechanisms that control peripheral and central terminal development of Aδ-low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs). Genes that are either are important for Aδ-LTMR development are indicated in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cell body. Signalling molecules that direct terminal development are indicated in the skin.

Aδ-LTMR Specification

Aδ-LTMRs can be identified based on their high expression of Ntrk2 in adulthood.18 Thus, they are likely to be derived from the NTRK2+ lineage (Figure 1). While Wnt1Cre (neural crest conditional); Shox2flox/flox mice do not survive past P6, adult analysis of Wnt1Cre; Shox2flox/+ mice shows a severe reduction in the number of NTRK2+ DRG neurons, suggesting that Shox2 is involved in Aδ-LTMR specification.39 In addition, while Pou4f2 is coexpressed with Pou4f1 by most DRG neurons around E15.5,93 genetic tracing of DRG neurons that express Pou4f2 around P0 exclusively labels neurons that match the peripheral terminal morphology and central innervation patterns of Aδ-LTMRs.94 However, analysis of Pou4f2 null mice and of DRG neurons after single-cell Pou4f2 deletion shows no obvious deficits in the specification or peripheral and central terminal development of Aδ-LTMRs,93,94 suggesting either that Pou4f2 plays a relatively minor role in the development of Aδ-LTMRs or its function is compensated by other transcriptional factors such as Pou4f1. While Maf is expressed by NTRK2+ cells at P15 (most likely Aδ-LTMRs), no obvious deficit is found upon physiological recordings from Maf mutant Aδ-LTMR units.35

Aδ-LTMR Central and Peripheral Development

Both BDNF and NTF5 signal through NTRK2.6 The terminal development of multiple Aβ-LTMR subtypes depends on BDNF–NTRK2 signaling and appears to be independent of NTF5 (see above).48,50 In contrast, Aδ-LTMR survival and development is highly dependent on NTF5–NTRK2 signaling (Figure 4). Ntf5 knockout mice show a depletion of Aδ-LTMR axons and a lack of Aδ-LTMR units in physiological recordings.95 Although Aδ-LTMRs are not dependent on BDNF for survival or for the development of mechanosensitive terminals,86 BDNF plays a role in localizing the lanceolate endings of these neurons. Aδ-LTMRs are localized to the caudal side of hair follicles and, consequently, these neurons preferentially respond to hair deflection in the caudal-to-rostral direction. Interestingly, BDNF is localized to the caudal side of the follicle, and conditional deletion of BDNF from the skin disrupts both the caudal localization of the neuronal terminals and the direction selectivity of these neurons.96 These results reveal differential roles for BDNF and NTF5 in Aδ-LTMR development.

Aδ-LTMRs are additionally dependent on NTF3 signaling. Ntf3 heterozygous mice have a ~50% reduction in the prevalence of Aδ-LTMR units recorded in skin-nerve preparations along with a reduction in Aδ caliber axons in the saphenous nerve.87 This result suggests either that Aδ-LTMR survival is dependent on NTRK3 signaling during early development or that NTF3 signaling may influence the expression of functional channels/ receptors that change physiological properties of Aδ-LTMRs.

As stated above, Shox2 neural crest conditional mutant mice show poorly developed lanceolate endings at P6, but it is difficult to determine if this phenotype includes Aδ-LTMRs or not.39 Consistent with physiological recordings, Maf sensory neuron conditional deletion does not affect NTRK2+/NEFH−(likely Aδ-LTMR) lanceolate endings.35

The molecular mechanisms controlling the central terminal development of Aδ-LTMRs are currently unclear. Shox2 neural crest conditional mutant mice have a reduction in sensory innervation of layers III/IV of the dorsal horn, but this reduction could be caused by deficits in the development of Aβ-LTMRs, Aδ-LTMRs, or both populations.40

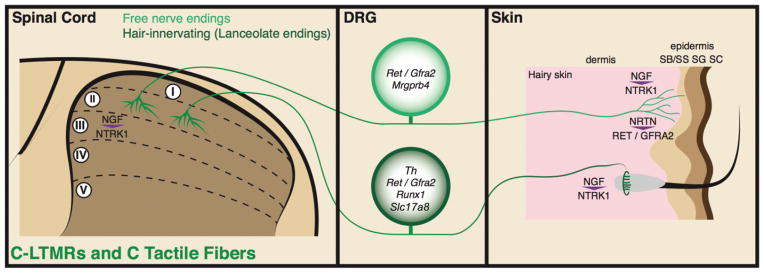

DEVELOPMENT OF C-LTMRs AND C TACTILE FIBERS

C fiber low-threshold mechanoreceptors, the slowest conducting mechanoreceptor subtypes, make up a surprisingly large fraction of DRG neurons (~15–30%)18 and may mediate the pleasurable component of affectionate social touch.97 In mice, one population of C fiber mechanoreceptors, which has been termed C-LTMRs, can be identified based on its expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (Th), Slc17a8 (formerly known as Vglut3), and Fam19a4.18,98–101 These neurons have intermediately adapting responses to sustained mechanical stimuli and respond to gentle mechanical force. They form lanceolate endings surrounding zigzag and awl/auchenne, but not guard, hair follicles in back hairy skin18 (Figure 5). A second potential type of mouse C fiber low-threshold mechanosensory fiber expresses the Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor member B4 (Mrgprb4).102,103 These fibers do not show any mechanical sensitivity in vitro. Nevertheless, in vivo calcium imaging suggests that they respond to pleasant stroking of the skin and could mediate light-touch.103 These neurons have therefore been termed C tactile fibers. MRGPRB4+ fibers terminate as free nerve endings in hairy skin, with each neuron innervating a large patch of skin102 (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Illustration showing molecular mechanisms that control peripheral and central terminal development of C-low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) and C tactile fibers. Genes that either specifically mark the C-LTMRs or C tactile fibers or are important for their development are indicated in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cell body. Signalling molecules that direct terminal development are indicated in the spinal cord and skin.

Like Aδ-LTMRs, C-LTMRs and C tactile fibers enter the spinal cord and send a single projection that runs rostrally for one or two segments. These projections send collaterals into the dorsal horn gray matter and form flame-shaped terminal arbors that terminate in layer II18,102 (Figure 5).

C-LTMR and C Tactile Fiber Specification

Both TH+ and MRGPRB4+ neurons are part of the NTRK1+ lineage, which are small diameter, unmyelinated neurons deriving from the Neurog1 wave of neurogenesis78 (see Figure 1). Similar to the role that Runx3 plays in the specification of the NTRK2+/ NTRK3+ lineage, Runx1 plays critical roles in the development of C fibers. One main function of Runx1 is to segregate NTRK1+ DRG neurons during prenatal and early postnatal development.5 Runx1 is initially expressed in almost all NTRK1+ neurons, but by E17.5, ~50% of NTRK1+ neurons have downregulated Runx1. Neurons that maintain Runx1 expression will express Ret and its coreceptors (the ‘late RET+’ population, including nonpeptidergic nociceptors, pruriceptors, and both populations of C fiber mechanorecptors), whereas those that decrease Runx1 expression will eventually express the neuropeptide Calca and become the peptidergic nociceptors.104 TH+ C-LTMRs maintain Runx1 expression into adulthood.99 In contrast, although Runx1 is required for the expression of Mrgprb4, MRGPRB4+ neurons downregulate Runx1 shortly after birth.104,105 Runx1 and the downstream zinc finger transcription factor Zfp521 form a transcriptional circuit that segregates TH+ C-LTMRs from MRGPRB4+ C tactile fibers and two other related C fiber populations (MRGPRD+ nonpeptidergic nociceptors and MRGPRA3+ pruriceptors). In this interaction, Runx1 promotes expression of Zfp521 and represses Mrgprb4 and Mrpra3 in future TH+ C-LTMRs. Zfp521 then acts to segregate TH+ C-LTMRs and MRGPRD+ nociceptors by promoting the expression of Th, Slc17a8, and Fam19a4 and repressing genes specific for nonpeptidergic nociceptors in TH+ C-LTMRs.100 Last, Runx1 regulates the mechanosensitivity of TH+ C-LTMRs by promoting the expression of the mechanosensor Piezo2.99 Recent transcriptional profiling of purified C-LTMRs revealed that their molecular profile is distinct from MRGPRD+ nociceptors but has a high degree of overlap with Aβ- and Aδ-LTMRs.106 This is interesting considering that C-fiber and A-fiber LTMRs have distinct developmental lineages (see above), suggesting that separate developmental mechanisms may converge to promote a common transcriptional profile for low-threshold mechanosensation.

NGF/NRTK1 signaling is necessary for the survival, specification, and central and peripheral terminal development (see below) of the NTRK1+ lineage. Both C-LTMRs and C tactile fibers do not survive in Ngf null mice.107 In Ngf−/−, Bax−/− double null mice (in which cell death is bypassed), these neurons fail to express Runx1, Ret, Gfra2, or the Mrg family of receptors, suggesting that NGF signalling is the master regulator for expression of functional genes in C fibers in addition to its role in survival.38 Last, while Ret is not required for survival of these neurons, neural crest conditional deletion of Ret results in a severe reduction of Mrgprb4 expression,38 indicating that RET signalling is necessary for MRGPB4+ neuron specification and/or functional gene expression.

C-LTMR and C Tactile Fiber Central and Peripheral Terminal Development

In addition to its role in survival and specification, NGF–NTRK1 signaling is required for both the peripheral and central innervation of all small-diameter NTRK1+ lineage neurons,108 including both TH+ and MRGPRB4+ C fiber mechanoreceptors (Figure 5). Runx1 also controls the development of their peripheral and central terminals. While TH+ C-LTMRs normally enwrap hair follicles and grow a palisade of longitudinal lanceolate endings, Runx1 mutant C-LTMRs still grow circumferential terminals around hair follicles but fail to form lanceolate endings.99 MRGPRB4+ neurons are part of a class of nonpeptidergic late RET+ neurons that bind the isolectin IB4.102 Runx1 has been shown to control the laminar position of IB4+ spinal cord projections, with Runx1 mutant projections terminating more dorsally in the dorsal horn than wildtype terminals.104 Since TH+ C-LTMRs do not bind IB4,18 it is unknown whether Runx1 plays a similar role in these neurons. Finally, neural crest conditional Ret deletion does not affect the survival of RUNX1+ neurons up to P14,38 and Gfra2 knockout does not affect the survival or peripheral terminal development of TH+ C-LTMRs.

CONCLUSION

This review has summarized the complex intrinsic and extrinsic molecular mechanisms that specify Aβ RA-, Aβ SA-, Aδ-, and C-LTMR neurons as well as guide their peripheral end organ formation and central projection wiring. All subtypes of mammalian LTMRs are derived from a common population of neural crest progenitors that delaminate from the developing neural tube. Early developmental events segregate this common progenitor pool into the early RET+ lineage (future Aβ RA-LTMRs), the NTRK3+ lineage (which includes Aβ SA-LTMRs), the NTRK2+ lineage (which includes Aδ-LTMRs), and the NTRK1+ lineage (which includes the late RET+ C-LTMRs and C tactile fibers). A specific combination of transcription factor and trophic factor activity within each lineage further orchestrates the development of their distinct end organs as well as their subtype-specific connectivity in the spinal cord.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

References

- 1.Willis WD, Coggeshall RE. Sensory Mechanisms of the Spinal Cord: Volume 1 Primary Afferent Neurons and the Spinal Dorsal Horn. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serbedzija GN, Fraser SE, Bronner-Fraser M. Pathways of trunk neural crest cell migration in the mouse embryo as revealed by vital dye labelling. Development. 1990;108:605–612. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Q, Fode C, Guillemot F, Anderson DJ. Neurogenin1 and neurogenin2 control two distinct waves of neurogenesis in developing dorsal root ganglia. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1717–1728. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson SN, Biscoe TJ. Development of mouse dorsal root ganglia: an autoradiographic and quantitative study. J Neurocytol. 1979;8:265–274. doi: 10.1007/BF01236122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer I, Sigrist M, de Nooij JC, Taniuchi I, Jessell TM, Arber S. A role for Runx transcription factor signaling in dorsal root ganglion sensory neuron diversification. Neuron. 2006;49:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fode C, Gradwohl G, Morin X, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Goridis C, Guillemot F. The bHLH protein NEURO-GENIN 2 is a determination factor for epibranchial placode-derived sensory neurons. Neuron. 1998;20:483–494. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80989-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fedtsova NG, Turner EE. Brn-3. 0 expression identifies early post-mitotic CNS neurons and sensory neural precursors. Mech Dev. 1995;53:291–304. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montelius A, Marmigere F, Baudet C, Aquino JB, Enerback S, Ernfors P. Emergence of the sensory nervous system as defined by Foxs1 expression. Differentiation. 2007;75:404–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng SR, Lanier J, Fedtsova N, Turner EE. Coordinated regulation of gene expression by Brn3a in developing sensory ganglia. Development. 2004;131:3859–3870. doi: 10.1242/dev.01260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y, Dykes IM, Liang X, Eng SR, Evans SM, Turner EE. A central role for Islet1 in sensory neuron development linking sensory and spinal gene regulatory programs. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1283–1293. doi: 10.1038/nn.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanier J, Dykes IM, Nissen S, Eng SR, Turner EE. Brn3a regulates the transition from neurogenesis to terminal differentiation and represses non-neural gene expression in the trigeminal ganglion. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:3065–3079. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dykes IM, Lanier J, Eng SR, Turner EE. Brn3a regulates neuronal subtype specification in the trigeminal ganglion by promoting Runx expression during sensory differentiation. Neural Dev. 2010;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dykes IM, Tempest L, Lee SI, Turner EE. Brn3a and Islet1 act epistatically to regulate the gene expression program of sensory differentiation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9789–9799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0901-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eng SR, Gratwick K, Rhee JM, Fedtsova N, Gan L, Turner EE. Defects in sensory axon growth precede neuronal death in Brn3a-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:541–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00541.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchard JW, Eade KT, Szucs A, Lo Sardo V, Tsunemoto RK, Williams D, Sanna PP, Baldwin KK. Selective conversion of fibroblasts into peripheral sensory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:25–35. doi: 10.1038/nn.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wainger BJ, Buttermore ED, Oliveira JT, Mellin C, Lee S, Saber WA, Wang AJ, Ichida JK, Chiu IM, Barrett L, et al. Modeling pain in vitro using nociceptor neurons reprogrammed from fibroblasts. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:17–24. doi: 10.1038/nn.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Rutlin M, Abraira VE, Cassidy C, Kus L, Gong S, Jankowski MP, Luo W, Heintz N, Koerber HR, et al. The functional organization of cutaneous low-threshold mechanosensory neurons. Cell. 2011;147:1615–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawson SN, Waddell PJ. Soma neurofilament immunoreactivity is related to cell size and fibre conduction velocity in rat primary sensory neurons. J Physiol. 1991;435:41–63. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo W, Enomoto H, Rice FL, Milbrandt J, Ginty DD. Molecular identification of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors and their developmental dependence on ret signaling. Neuron. 2009;64:841–856. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iggo A, Ogawa H. Correlative physiological and morphological studies of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors in cat’s glabrous skin. J Physiol. 1977;266:275–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pare M, Smith AM, Rice FL. Distribution and terminal arborizations of cutaneous mechanoreceptors in the glabrous finger pads of the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:347–359. doi: 10.1002/cne.10196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talbot WH, Darian-Smith I, Kornhuber HH, Mountcastle VB. The sense of flutter-vibration: comparison of the human capacity with response patterns of mechanoreceptive afferents from the monkey hand. J Neurophysiol. 1968;31:301–334. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell J, Bolanowski S, Holmes MH. The structure and function of Pacinian corpuscles: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;42:79–128. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelena J. Nerves and Mechanoreceptors. London: Chapman & Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki M, Ebara S, Koike T, Tonomura S, Kumamoto K. How many hair follicles are innervated by one afferent axon? A confocal microscopic analysis of palisade endings in the auricular skin of thy1-YFP transgenic mouse. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2012;88:583–595. doi: 10.2183/pjab.88.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown A. Organization in the Spinal Cord: The Anatomy and Physiology of Identified Neurones. Springer-Verlag; Berlin and New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu J, Ding L, Li JJ, Kim H, Liu J, Li H, Moberly A, Badea TC, Duncan ID, Son YJ, et al. Modality-based organization of ascending somatosensory axons in the direct dorsal column pathway. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17691–17709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3429-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semba K, Masarachia P, Malamed S, Jacquin M, Harris S, Yang G, Egger MD. An electron microscopic study of terminals of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptive afferent fibers in the cat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1985;232:229–240. doi: 10.1002/cne.902320208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shortland P, Woolf CJ. Morphology and somatotopy of the central arborizations of rapidly adapting glabrous skin afferents in the rat lumbar spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 1993;329:491–511. doi: 10.1002/cne.903290406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown AG, Fyffe RE, Noble R. Projections from Pacinian corpuscles and rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors of glabrous skin to the cat’s spinal cord. J Physiol. 1980;307:385–400. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semba K, Masarachia P, Malamed S, Jacquin M, Harris S, Egger MD. Ultrastructure of pacinian corpuscle primary afferent terminals in the cat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1984;302:135–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodbury CJ, Ritter AM, Koerber HR. Central anatomy of individual rapidly adapting low-threshold mechanoreceptors innervating the “hairy” skin of newborn mice: early maturation of hair follicle afferents. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:304–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourane S, Garces A, Venteo S, Pattyn A, Hubert T, Fichard A, Puech S, Boukhaddaoui H, Baudet C, Takahashi S, et al. Low-threshold mechanoreceptor subtypes selectively express MafA and are specified by Ret signaling. Neuron. 2009;64:857–870. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wende H, Lechner SG, Cheret C, Bourane S, Kolanczyk ME, Pattyn A, Reuter K, Munier FL, Carroll P, Lewin GR, et al. The transcription factor c-Maf controls touch receptor development and function. Science. 2012;335:1373–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.1214314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, Abdo H, Lonnerberg P, Lou D, Hjerling-Lefffler J, Haeggstrom J, Kharchenko O, Kharchenko PV, et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:145–153. doi: 10.1038/nn.3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu J, Huang T, Li T, Guo Z, Cheng L. c-Maf is required for the development of dorsal horn laminae III/IV neurons and mechanoreceptive DRG axon projections. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5362–5373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6239-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo W, Wickramasinghe SR, Savitt JM, Griffin JW, Dawson TM, Ginty DD. A hierarchical NGF signaling cascade controls Ret-dependent and Ret-independent events during development of nonpeptidergic DRG neurons. Neuron. 2007;54:739–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdo H, Li L, Lallemend F, Bachy I, Xu XJ, Rice FL, Ernfors P. Dependence on the transcription factor Shox2 for specification of sensory neurons conveying discriminative touch. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:1529–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott A, Hasegawa H, Sakurai K, Yaron A, Cobb J, Wang F. Transcription factor short stature homeobox 2 is required for proper development of tropomyosin-related kinase B-expressing mechanosensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6741–6749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5883-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honma Y, Kawano M, Kohsaka S, Ogawa M. Axonal projections of mechanoreceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons depend on Ret. Development. 2010;137:2319–2328. doi: 10.1242/dev.046995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paratcha G, Ledda F, Baars L, Coulpier M, Besset V, Anders J, Scott R, Ibanez CF. Released GFR∝1 potentiates downstream signaling, neuronal survival, and differentiation via a novel mechanism of recruitment of c-Ret to lipid rafts. Neuron. 2001;29:171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ledda F, Paratcha G, Ibanez CF. Target-derived GFR∝1 as an attractive guidance signal for developing sensory and sympathetic axons via activation of Cdk5. Neuron. 2002;36:387–401. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trupp M, Belluardo N, Funakoshi H, Ibanez CF. Complementary and overlapping expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), c-ret proto-oncogene, and GDNF receptor-∝ indicates multiple mechanisms of trophic actions in the adult rat CNS. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3554–3567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu T, Scully S, Yu Y, Fox GM, Jing S, Zhou R. Expression of GDNF family receptor components during development: implications in the mechanisms of interaction. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4684–4696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04684.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleming MS, Vysochan A, Paixao S, Niu J, Klein R, Savitt JM, Luo W. Cis- and trans-RET signaling control the survival and central projection growth of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors. Elife. 2015;4:e06828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez-Martinez T, Germana GP, Monjil DF, Silos-Santiago I, de Carlos F, Germana G, Cobo J, Vega JA. Absence of Meissner corpuscles in the digital pads of mice lacking functional TrkB. Brain Res. 2004;1002:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zelena J, Jirmanova I, Nitatori T, Ide C. Effacement and regeneration of tactile lamellar corpuscles of rat after postnatal nerve crush. Neuroscience. 1990;39:513–522. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90287-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez-Martinez T, Farinas I, Del Valle ME, Feito J, Germana G, Cobo J, Vega JA. BDNF, but not NT-4, is necessary for normal development of Meissner corpuscles. Neurosci Lett. 2005;377:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perez-Pinera P, Garcia-Suarez O, Germana A, Diaz-Esnal B, de Carlos F, Silos-Santiago I, del Valle ME, Cobo J, Vega JA. Characterization of sensory deficits in TrkB knockout mice. Neurosci Lett. 2008;433:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ernfors P, Lee KF, Jaenisch R. Mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor develop with sensory deficits. Nature. 1994;368:147–150. doi: 10.1038/368147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calavia MG, Feito J, Lopez-Iglesias L, de Carlos F, Garcia-Suarez O, Perez-Pinera P, Cobo J, Vega JA. The lamellar cells in human Meissner corpuscles express TrkB. Neurosci Lett. 2010;468:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LeMaster AM, Krimm RF, Davis BM, Noel T, Forbes ME, Johnson JE, Albers KM. Overexpression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances sensory innervation and selectively increases neuron number. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5919–5931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05919.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krimm RF, Davis BM, Noel T, Albers KM. Overexpression of neurotrophin 4 in skin enhances myelinated sensory endings but does not influence sensory neuron number. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:455–465. doi: 10.1002/cne.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sedy J, Szeder V, Walro JM, Ren ZG, Nanka O, Tessarollo L, Sieber-Blum M, Grim M, Kucera J. Pacinian corpuscle development involves multiple Trk signaling pathways. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:551–563. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sedy J, Tseng S, Walro JM, Grim M, Kucera J. ETS transcription factor ER81 is required for the Pacinian corpuscle development. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1081–1089. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iggo A, Muir AR. The structure and function of a slowly adapting touch corpuscle in hairy skin. J Physiol. 1969;200:763–796. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maricich SM, Morrison KM, Mathes EL, Brewer BM. Rodents rely on Merkel cells for texture discrimination tasks. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3296–3300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5307-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niu J, Vysochan A, Luo W. Dual innervation of neonatal Merkel cells in mouse touch domes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maksimovic S, Nakatani M, Baba Y, Nelson AM, Marshall KL, Wellnitz SA, Firozi P, Woo SH, Ranade S, Patapoutian A, et al. Epidermal Merkel cells are mechanosensory cells that tune mammalian touch receptors. Nature. 2014;509:617–621. doi: 10.1038/nature13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woo SH, Ranade S, Weyer AD, Dubin AE, Baba Y, Qiu Z, Petrus M, Miyamoto T, Reddy K, Lumpkin EA, et al. Piezo2 is required for Merkel-cell mechanotransduction. Nature. 2014;509:622–626. doi: 10.1038/nature13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ikeda R, Cha M, Ling J, Jia Z, Coyle D, Gu JG. Merkel cells transduce and encode tactile stimuli to drive Aβ-afferent impulses. Cell. 2014;157:664–675. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ranade SS, Woo SH, Dubin AE, Moshourab RA, Wetzel C, Petrus M, Mathur J, Begay V, Coste B, Mainquist J, et al. Piezo2 is the major transducer of mechanical forces for touch sensation in mice. Nature. 2014;516:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature13980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gottschaldt KM, Vahle-Hinz C. Merkel cell receptors: structure and transducer function. Science. 1981;214:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.7280690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tachibana T, Nawa T. Recent progress in studies on Merkel cell biology. Anat Sci Int. 2002;77:26–33. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-7722.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haeberle H, Fujiwara M, Chuang J, Medina MM, Panditrao MV, Bechstedt S, Howard J, Lumpkin EA. Molecular profiling reveals synaptic release machinery in Merkel cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406308101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fagan BM, Cahusac PM. Evidence for glutamate receptor mediated transmission at mechanoreceptors in the skin. Neuroreport. 2001;12:341–347. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maricich SM, Wellnitz SA, Nelson AM, Lesniak DR, Gerling GJ, Lumpkin EA, Zoghbi HY. Merkel cells are essential for light-touch responses. Science. 2009;324:1580–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.1172890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnson KO, Yoshioka T, Vega-Bermudez F. Tactile functions of mechanoreceptive afferents innervating the hand. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;17:539–558. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johansson RS, Vallbo AB. Tactile sensibility in the human hand: relative and absolute densities of four types of mechanoreceptive units in glabrous skin. J Physiol. 1979;286:283–300. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chambers MR, Andres KH, von Duering M, Iggo A. The structure and function of the slowly adapting type II mechanoreceptor in hairy skin. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1972;57:417–445. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1972.sp002177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rasmusson DD, Turnbull BG. Sensory innervation of the raccoon forepaw: 2. Response properties and classification of slowly adapting fibers. Somatosens Res. 1986;4:63–75. doi: 10.3109/07367228609144598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rice FL, Rasmusson DD. Innervation of the digit on the forepaw of the raccoon. J Comp Neurol. 2000;417:467–490. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000221)417:4<467::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pare M, Behets C, Cornu O. Paucity of presumptive Ruffini corpuscles in the index finger pad of humans. J Comp Neurol. 2003;456:260–266. doi: 10.1002/cne.10519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wellnitz SA, Lesniak DR, Gerling GJ, Lumpkin EA. The regularity of sustained firing reveals two populations of slowly adapting touch receptors in mouse hairy skin. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:3378–3388. doi: 10.1152/jn.00810.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cronk KM, Wilkinson GA, Grimes R, Wheeler EF, Jhaveri S, Fundin BT, Silos-Santiago I, Tessarollo L, Reichardt LF, Rice FL. Diverse dependencies of developing Merkel innervation on the trkA and both full-length and truncated isoforms of trkC. Development. 2002;129:3739–3750. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marmigere F, Ernfors P. Specification and connectivity of neuronal subtypes in the sensory lineage. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:114–127. doi: 10.1038/nrn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Senzaki K, Ozaki S, Yoshikawa M, Ito Y, Shiga T. Runx3 is required for the specification of TrkC-expressing mechanoreceptive trigeminal ganglion neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;43:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yoshikawa M, Murakami Y, Senzaki K, Masuda T, Ozaki S, Ito Y, Shiga T. Coexpression of Runx1 and Runx3 in mechanoreceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2013;73:469–479. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grim M, Halata Z. Developmental origin of avian Merkel cells. Anat Embryol. 2000;202:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s004290000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Szeder V, Grim M, Halata Z, Sieber-Blum M. Neural crest origin of mammalian Merkel cells. Dev Biol. 2003;253:258–263. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morrison KM, Miesegaes GR, Lumpkin EA, Maricich SM. Mammalian Merkel cells are descended from the epidermal lineage. Dev Biol. 2009;336:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Montano JA, Perez-Pinera P, Garcia-Suarez O, Cobo J, Vega JA. Development and neuronal dependence of cutaneous sensory nerve formations: lessons from neurotrophins. Microsc Res Tech. 2010;73:513–529. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fundin BT, Silos-Santiago I, Ernfors P, Fagan AM, Aldskogius H, DeChiara TM, Phillips HS, Barbacid M, Yancopoulos GD, Rice FL. Differential dependency of cutaneous mechanoreceptors on neurotrophins, trk receptors, and P75 LNGFR. Dev Biol. 1997;190:94–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carroll P, Lewin GR, Koltzenburg M, Toyka KV, Thoenen H. A role for BDNF in mechanosensation. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:42–46. doi: 10.1038/242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Airaksinen MS, Koltzenburg M, Lewin GR, Masu Y, Helbig C, Wolf E, Brem G, Toyka KV, Thoenen H, Meyer M. Specific subtypes of cutaneous mechanoreceptors require neurotrophin-3 following peripheral target innervation. Neuron. 1996;16:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kinkelin I, Stucky CL, Koltzenburg M. Postnatal loss of Merkel cells, but not of slowly adapting mechanoreceptors in mice lacking the neurotrophin receptor p75. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3963–3969. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matsuo S, Ichikawa H, Silos-Santiago I, Kiyomiya K, Kurebe M, Arends JJ, Jacquin MF. Ruffini endings are absent from the periodontal ligament of trkB knockout mice. Somatosens Mot Res. 2002;19:213–217. doi: 10.1080/0899022021000009134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoshino N, Harada F, Alkhamrah BA, Aita M, Kawano Y, Hanada K, Maeda T. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the development of periodontal Ruffini endings. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;274:807–816. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maruyama Y, Harada F, Jabbar S, Saito I, Aita M, Kawano Y, Suzuki A, Nozawa-Inoue K, Maeda T. Neurotrophin-4/5-depletion induces a delay in maturation of the periodontal Ruffini endings in mice. Arch Histol Cytol. 2005;68:267–288. doi: 10.1679/aohc.68.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Light AR, Perl ER. Spinal termination of functionally identified primary afferent neurons with slowly conducting myelinated fibers. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:133–150. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zou M, Li S, Klein WH, Xiang M. Brn3a/Pou4f1 regulates dorsal root ganglion sensory neuron specification and axonal projection into the spinal cord. Dev Biol. 2012;364:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Badea TC, Williams J, Smallwood P, Shi M, Motajo O, Nathans J. Combinatorial expression of Brn3 transcription factors in somatosensory neurons: genetic and morphologic analysis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:995–1007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4755-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stucky CL, DeChiara T, Lindsay RM, Yancopoulos GD, Koltzenburg M. Neurotrophin 4 is required for the survival of a subclass of hair follicle receptors. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7040–7046. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-07040.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rutlin M, Ho CY, Abraira VE, Cassidy C, Bai L, Woodbury CJ, Ginty DD. The cellular and molecular basis of direction selectivity of Adelta-LTMRs. Cell. 2014;159:1640–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Olausson H, Lamarre Y, Backlund H, Morin C, Wallin BG, Starck G, Ekholm S, Strigo I, Worsley K, Vallbo AB, et al. Unmyelinated tactile afferents signal touch and project to insular cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:900–904. doi: 10.1038/nn896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seal RP, Wang X, Guan Y, Raja SN, Woodbury CJ, Basbaum AI, Edwards RH. Injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity requires C-low threshold mechanoreceptors. Nature. 2009;462:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature08505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lou S, Duan B, Vong L, Lowell BB, Ma Q. Runx1 controls terminal morphology and mechanosensitivity of VGLUT3-expressing C-mechanoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2013;33:870–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3942-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lou S, Pan X, Huang T, Duan B, Yang FC, Yang J, Xiong M, Liu Y, Ma Q. Incoherent feed-forward regulatory loops control segregation of C-mechanoreceptors, nociceptors, and pruriceptors. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5317–5329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0122-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delfini MC, Mantilleri A, Gaillard S, Hao J, Reynders A, Malapert P, Alonso S, Francois A, Barrere C, Seal R, et al. TAFA4, a chemokine-like protein, modulates injury-induced mechanical and chemical pain hypersensitivity in mice. Cell Rep. 2013;5:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu Q, Vrontou S, Rice FL, Zylka MJ, Dong X, Anderson DJ. Molecular genetic visualization of a rare subset of unmyelinated sensory neurons that may detect gentle touch. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:946–948. doi: 10.1038/nn1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Vrontou S, Wong AM, Rau KK, Koerber HR, Anderson DJ. Genetic identification of C fibres that detect massage-like stroking of hairy skin in vivo. Nature. 2013;493:669–673. doi: 10.1038/nature11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen CL, Broom DC, Liu Y, de Nooij JC, Li Z, Cen C, Samad OA, Jessell TM, Woolf CJ, Ma Q. Runx1 determines nociceptive sensory neuron phenotype and is required for thermal and neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006;49:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Y, Yang FC, Okuda T, Dong X, Zylka MJ, Chen CL, Anderson DJ, Kuner R, Ma Q. Mechanisms of compartmentalized expression of Mrg class G-protein-coupled sensory receptors. J Neurosci. 2008;28:125–132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4472-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reynders A, Mantilleri A, Malapert P, Rialle S, Nidelet S, Laffray S, Beurrier C, Bourinet E, Moqrich A. Transcriptional profiling of cutaneous MRGPRD free nerve endings and C-LTMRs. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Crowley C, Spencer SD, Nishimura MC, Chen KS, Pitts-Meek S, Armanini MP, Ling LH, McMahon SB, Shelton DL, Levinson AD, et al. Mice lacking nerve growth factor display perinatal loss of sensory and sympathetic neurons yet develop basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Cell. 1994;76:1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Patel TD, Jackman A, Rice FL, Kucera J, Snider WD. Development of sensory neurons in the absence of NGF/TrkA signaling in vivo. Neuron. 2000;25:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FURTHER READING

- Abraira VE, Ginty DD. The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron. 2013;21:618–639. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MS, Luo W. The anatomy, function, and development of mammalian Aβ low-threshold mechanoreceptors. Front biol. 2013;8:408–420. doi: 10.1007/s11515-013-1271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemend F, Ernfors P. Molecular interactions underlying the specification of sensory neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]