Abstract

Purpose

To examine the relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and the risk of having open-angle glaucoma (OAG) in an adult Latino population.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Participants

Latinos 40 years and older (n = 5894) from 6 census tracts in Los Angeles, California.

Methods

Participants from the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES), a large population-based study of self-identified adult Latinos, answered an interviewer-administered questionnaire and underwent a clinical and complete ocular examination, including visual field (VF) testing and stereo fundus photography. A participant was defined as having diabetes mellitus (DM) if she or he had a history of being treated for DM, the participant’s glycosylated hemoglobin was measured at 7.0% or higher, or the participant had random blood glucose of 200 mg% or higher. Type 2 DM was defined if the participant was 30 years or older when diagnosed with DM. Open-angle glaucoma was defined as the presence of an open angle and a glaucomatous VF abnormality and/or evidence of glaucomatous optic disc damage in at least one eye. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the risk of having OAG in persons with T2DM.

Main Outcome Measure

Prevalence of OAG.

Results

Of the 5894 participants with complete data, 1157 (19.6%) had T2DM and 288 (4.9%) had OAG. The prevalence of OAG was 40% higher in participants with T2DM than in those without T2DM (age/gender/intraocular pressure–adjusted odds ratio, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.8; P = 0.03). Trend analysis revealed that a longer duration of T2DM (stratified into 5-year increments) was associated with a higher prevalence of OAG (P<0.0001).

Conclusion

The presence of T2DM and a longer duration of T2DM were independently associated with a higher risk of having OAG in the LALES cohort. The high prevalences of T2DM and OAG and their association in this fastest growing segment of the United States population have significant implications for designing screening programs targeting Latinos.

Open-angle glaucoma (OAG) is estimated to afflict 66.8 million people worldwide1 and is a leading cause of blindness. 2 Racial and ethnic differences exist between prevalence rates and severity of glaucoma as demonstrated by numerous population-based studies, including the Beaver Dam Eye Study,3 Baltimore Eye Survey,4 Barbados Eye Study,5 Blue Mountains Eye Study,6 Rotterdam Study,7 Visual Impairment Project,8 Proyecto VER (Vision and Eye Research),9 and Nurses’ Health Study (NHS).10 The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES) reported a high prevalence of OAG (4.7%) in United States Latinos with a predominantly Mexican ancestry, comparable to that of U.S. blacks and significantly higher than that of non-Hispanic whites.11 The commonly accepted risk factors for OAG include increasing age, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), family history, and race.

The relationship between diabetes mellitus (DM) and OAG, however, remains unclear. Four previous populationbased studies (Baltimore Eye Survey,12 Rotterdam Study,13 Proyecto VER,9 and Visual Impairment Project8) found no association between DM and OAG. Three others (Beaver Dam Eye Study,14 Blue Mountains Eye Study,6 and NHS10) reported significant associations. Furthermore, limited data exist on the relationship between DM and OAG among U.S. Latinos, the largest minority group (12.5%) and the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population.15–17 To understand the relationship between DM and the risk of having openangle glaucoma (OAG) better, we examined data from the LALES. This report presents these data and explores this relationship in a population-based sample of Latinos with a high prevalence of type 2 DM (T2DM).

Participants and Methods

Design

Participants were identified through the LALES,18 a large population-based survey, from 2000 to 2003. The LALES was designed to estimate the prevalence of ocular disease, associated risk factors, quality of life, and access to health care in noninstitutionalized self-identified adult Latinos, 40 years and older, living in the city of La Puente, California. The LALES survey methods and socioeconomic characteristics of LALES participants have been described in detail previously.18 In the LALES, 82% (n = 6357) of eligible persons (n = 7789) completed the clinical examination. 18 Participants with incomplete data (n = 463) were excluded from the analyses. Thus, our cross-sectional study cohort consisted of 5894 consecutively enrolled adult Latinos, predominantly of Mexican ancestry, who completed an in-home interview and a complete clinical eye examination, as well as additional laboratory testing for diabetes. The institutional review board at the University of Southern California approved the study protocol, and all study procedures conformed to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human participants.

Clinical Procedures and Definitions

After informed consent was obtained, participants underwent a complete ophthalmic examination, including determination of visual acuity and refraction and slit-lamp examination, as detailed previously.18 Three measurements of IOP were obtained using the Goldmann applanation tonometry (Haag-Streit, Bern, Switzerland) and averaged to yield a single value for each eye. Visual field (VF) testing was performed using the Humphrey Automated Field Analyzer (Zeiss, Humphrey, CA; Swedish interactive threshold algorithm Standard 24-2) in each eye. If the VF results were normal, then no additional VF testing was done. However, a repeat VF test was performed if the initial VF results were unreliable or abnormal. After maximal dilation, a detailed posterior segment examination and stereo optic disc and fundus photography were performed using a TRC 50EX Retinal Camera (Topcon Corp. of America, Paramus, NJ) and Ektachrome 100 film (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

In addition, an interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to assess ocular and medical histories, and laboratory testing was performed to obtain objective diagnostic criteria. The criteria for diagnosing T2DM in the LALES have been reported previously. 19 In brief, a participant was considered to have T2DM if any of the following criteria were met: (1) self-reported history of diabetes and treatment with oral hypoglycemic medications, insulin, or diet alone, (2) hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of 7.0% or higher using the DCA 2000+ System (Bayer Corp., Tarrytown, NY), or (3) random blood glucose of 200 mg/100 ml or higher using the Hemocue B-Glucose Analyzer (Hemocue Inc., Lake Forest, CA). The duration of T2DM was calculated as the difference between the year of diagnosis (as reported by participant) and year of the LALES examination. Newly diagnosed diabetics were assigned a duration of 0 years. Participants were considered to have T1DM if they were younger than 30 years at the time of their DM diagnosis and if they were receiving insulin therapy. In the current study, participants with T1DM (n = 23) were excluded from the subsequent analysis for 2 reasons. First, there were too few cases of T1DM participants in the LALES population, limiting our ability to draw conclusions. Second, there are likely differences in pathophysiology, risk of associated complications, and duration of disease processes between T1DM and T2DM.

The criteria for diagnosing glaucoma in the LALES have been described in detail previously.18 In brief, definite or probable OAG was defined as the presence of an open angle and (1) evidence of characteristic or compatible glaucomatous optic disc damage on stereo fundus photography in at least one eye and/or (2) congruent, characteristic, or compatible glaucomatous VF abnormality. The IOP level was not considered in establishing the diagnosis of OAG, and thus, no differentiation was made between low-tension OAG and high-tension OAG. Using a stereoscopic viewer (Asahi, Pentax, Englewood, CO), simultaneous stereoscopic optic disc photographs were used by 2 glaucoma specialists to characterize optic nerve findings in terms of vertical and horizontal cup-to-disc (C/D) ratios, C/D ratio asymmetry between the 2 eyes, disc and peripapillary nerve fiber layer hemorrhage, peripapillary atrophy, diffuse thinning of the neural rim (remaining neural rim < 0.1), and notching of the neural rim (remaining neural rim in a localized area < 0.1). Glaucomatous optic neuropathy was classified as characteristic if it met ≥2 of the following criteria and compatible if it met 1 of the following: horizontal or vertical C/D ratio ≥ 0.8, notching of neural rim, localized or diffuse loss of neural rim with a maximum remaining neural rim of <0.1, or nerve fiber layer defect in the arcuate bundles. Furthermore, 2 glaucoma specialists graded the VF loss as characteristic or compatible with glaucoma, due to other nonglaucomatous/neurologic cause or artifact; or not determinable/not applicable, based on the optic disc evaluation, clinical examination data, and evaluation of disc and fundus photographs. Visual field defects corresponding to the nerve fiber layer bundle pattern, which included nasal steps (either superior or inferior, but not both), paracentral defect, arcuate defect, central island, temporal island, and absolute defect, were defined as characteristic of glaucoma. Visual field defects that conform to nerve fiber bundle loss but have deviated in some manner from the characteristic defects, including altitudinal loss, both superior and inferior nasal steps, and defects with fair convergence, including a VF defect present in one VF but not in the second VF test (defects in the nasal, arcuate, or paracentral regions), were defined as compatible with glaucoma.

Statistical Analyses

The t test and chi-square test procedures were used to assess the univariate associations between demographic or clinical risk factors and OAG vs. no OAG. Trend analysis was performed using the Mantel–Haenszel χ2 procedure. Unadjusted and age/gender/IOP–adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to assess the association between risk factors (including T2DM) and OAG. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. In addition, 2 additional sets of statistical analyses were also carried out after excluding all participants with evidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and after excluding all participants with any form of diabetic retinopathy. All analyses were conducted at a ≤0.05 significance level using SAS programs (version 8, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To examine the nature of the relationship between duration of T2DM and probability of having OAG, we used an iterative, locally weighted, least-squares method to plot the best-fit line.

Results

In the LALES, 82% (6357/7789) of eligible participants completed the interview and clinical examination.18 Details regarding nonparticipants have been described.18 From the 6357 participants, the cohort for this study includes 5894 participants who had completed the interview and clinical examination and had their blood glucose levels determined (HbA1c and random blood glucose). The majority of participants were female (58%), the average age (± standard deviation) was 54.9±10.9 years, 94.7% were of Mexican American ancestry, and 76% of participants were born outside the U.S.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of persons with and without OAG are presented in Table 1. In our population, the prevalence of T2DM was 19.6%, and that of OAG was 4.9%. The results of the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 2. In the unadjusted analyses, older age, male gender, higher mean IOP, presence of T2DM, HbA1c level ≥ 7.0%, and duration of T2DM > 10 years were associated with OAG. After adjusting for covariates (age, gender, and IOP), the independent risk factors for OAG included presence of T2DM and duration of T2DM ≥ 15 years.

Table 1.

Frequency Distribution of Risk Factors for Open-angle Glaucoma (OAG) in Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Participants

| Risk Factors for OAG | Total (N = 5894) (100%) |

OAG (n = 288) (4.9%) |

No OAG (n = 5606) (95.1%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | <0.0001 | |||

| 40–49 | 2311 (39.2) | 30 (10.4) | 2281 (40.7) | |

| 50–59 | 1762 (29.9) | 52 (18.1) | 1710 (30.5) | |

| 60–69 | 1134 (19.2) | 88 (30.6) | 1046 (18.7) | |

| 70–79 | 551 (9.4) | 85 (29.5) | 466 (8.3) | |

| ≥80 | 136 (2.3) | 33 (11.5) | 103 (1.8) | |

| Gender (male) | 2473 (42.0) | 137 (47.6) | 2336 (41.7) | 0.048 |

| Mean IOP (mmHg) | 14.3 (3.0) | 17.3 (5.4) | 14.1 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Presence of T2DM | 1157 (19.6) | 94 (32.8) | 1063 (19.0) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c ≥ 7.0% | 868 (14.8) | 63 (22.3) | 805 (14.5) | 0.0003 |

| Random blood glucose ≥ 200 mg% | 497 (8.5) | 30 (10.6) | 467 (8.4) | 0.18 |

| Duration of T2DM (yrs) | <0.0001 | |||

| No DM | 4736 (80.4) | 193 (67.2) | 4543 (81.1) | |

| New case | 231 (3.9) | 16 (5.6) | 215 (3.8) | |

| <5 | 323 (5.5) | 21 (7.3) | 302 (5.4) | |

| 5–9 | 223 (3.8) | 15 (5.2) | 208 (3.7) | |

| 10–14 | 174 (3.0) | 16 (5.6) | 158 (2.8) | |

| ≥15 | 202 (3.4) | 26 (9.1) | 176 (3.1) |

CI = confidence interval; DM = diabetes mellitus; IOP = intraocular pressure; OR = odds ratio; T2DM = type 2 DM.

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) for IOP and frequency (%) for all other variables. Frequency is based on the total no. of participants for each item and varies depending on missing data for a specific item. P values were calculated using t test for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables.

Table 2.

Associations between Risk Factors and Open-angle Glaucoma (OAG) by Logistic Regression Analysis in Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Participants

|

Unadjusted OR

|

Adjusted OR

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors for OAG | N * | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age (yrs) | <0.0001 | ||||

| 40–49 | 2311 | 1.0 | |||

| 50–59 | 1762 | 2.3 (1.5–3.6) | 0.0003 | ||

| 60–69 | 1134 | 6.4 (4.2–9.7) | <0.0001 | ||

| 70–79 | 551 | 13.9 (9.0–21.3) | <0.0001 | ||

| ≥80 | 136 | 24.4 (14.3–41.5) | <0.0001 | ||

| Gender (male) | 2473 | 1.3 (1.002–1.6) | 0.048 | ||

| Mean IOP | 5842 | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) | <0.0001 | ||

| Presence of T2DM | 1157 | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.03–1.8) | 0.03 |

| Hemoglobin A1c ≥ 7% | 868 | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 0.0003 | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.21 |

| Random glucose ≥ 200 mg% | 497 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 0.18 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 0.44 |

| Duration of T2DM (yrs) | <0.0001 | 0.26 | |||

| No DM | 4736 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| New case | 231 | 1.8 (1.03–3.0) | 0.04 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 0.22 |

| <5 | 323 | 1.6 (1.03–2.6) | 0.03 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | 0.65 |

| 5–9 | 223 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | 0.06 | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 0.36 |

| 10–14 | 174 | 2.4 (1.4–4.1) | 0.001 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 0.30 |

| ≥15 | 202 | 3.5 (2.2–5.4) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.04–2.8) | 0.03 |

CI = confidence interval; DM = diabetes mellitus; IOP = intraocular pressure; OR = odds ratio; T2DM = type 2 DM.

Odds ratios were adjusted for age, gender, and IOP.

Only for univariate logistic analysis. Only those without missing data were included in the analysis.

The presence of T2DM was independently associated with a higher risk of having OAG (age/gender/IOP–adjusted OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.03–1.8; P = 0.03). The statistical analysis was also rerun using a more strict definition of DM, which excluded all participants with self-reported DM on diet alone (who were not being treated with antidiabetic pills or insulin or did not have elevated blood sugar values). With the stricter definition of DM, the results were essentially unchanged (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02–1.79; P = 0.035), showing a positive association between T2DM and OAG.

Although a detailed slit-lamp examination was performed on every participant by a LALES ophthalmologist to exclude any evidence of rubeosis iridis, gonioscopy to assess the anterior chamber angle was not performed in every participant. It is, therefore, theoretically possible that a participant had evidence of angle neovascularization without clinically detectable rubeosis iridis, especially if the participant had advanced diabetic retinopathy. Thus, to exclude any possibility that a participant with neovascular glaucoma might have been misclassified as OAG, the entire statistical analysis was performed excluding all participants with PDR, the most severe form of diabetic microvascular disease, which is classically associated with neovascular glaucoma. Our results remained unchanged, and the relationship between T2DM and OAG was found to remain significant (age/gender/IOP–adjusted OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.01–1.77; P = 0.04). Furthermore, the analysis was also rerun by excluding all participants with any DR (in case there was macular/retinal ischemia without signs of PDR leading to neovascular glaucoma), and the presence of T2DM continued to be independently associated with a higher prevalence of OAG (age/gender/IOP–adjusted OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.06 –1.82; P = 0.016).

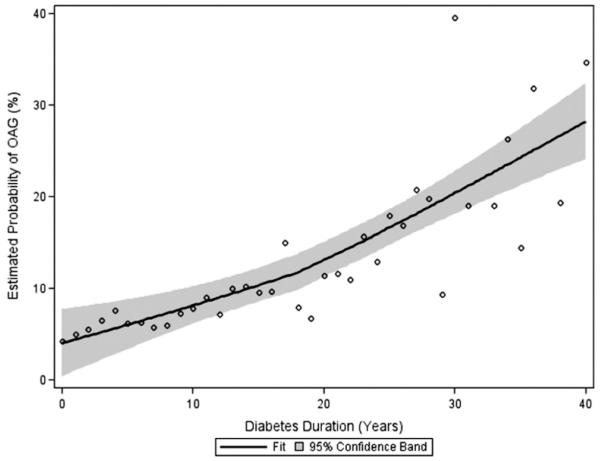

In addition, there was a higher risk of having OAG in participants with duration of T2DM ≥ 15 years (age/gender/IOP–adjusted OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.04–2.8; P = 0.03). To illustrate the independent relationship between the probability of having OAG and duration of T2DM, we plotted the LOWESS fit20 after adjusting for age, gender, and IOP (Fig 1). The plot suggests that, independent of other risk factors, participants with longer duration of diabetes are more likely to have OAG. Furthermore, trend analysis using the Mantel–Haenszel chi-square procedure revealed a significant relationship between longer duration of T2DM (in 5-year increments) and higher risk of OAG (P<0.0001). Finally, stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relative impact of each significant variable after adjusting for covariates (age, gender, IOP). The presence of T2DM was found to be the most statistically significant variable that was independently associated with OAG.

Figure 1.

Duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus versus estimated probability of open-angle glaucoma (OAG) in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study participants. The LOWESS20 plot (a locally weighted regression), with 95% confidence intervals, uses an iterative, locally weighted, least-squares method to plot the best-fit line and has been adjusted for age, gender, and intraocular pressure.

Discussion

The current study reports on the positive, independent association between T2DM and OAG in this sample population, which has a high prevalence of both T2DM and OAG. In the LALES, the prevalence of OAG was 40% higher in participants with T2DM than in those without. To the best of our knowledge, the LALES is the first report of an independent association between T2DM and OAG in a U.S. Latino population. This concurs with other large population-based crosssectional studies of predominantly whites, including the Beaver Dam Eye Study, Blue Mountains Eye Study, and NHS, all of which found that persons with DM have an independent higher risk of having OAG than those without DM.6,10,14 In particular, similar to the LALES, the Blue Mountains Eye Study reported a significant and consistent association between DM and OAG, independent of level of IOP.

In contrast, unlike these previously reported studies of primarily white populations, the Baltimore Eye Survey examined a more varied population (45% black) and found no association between primary OAG and history of T2DM.12 The variance in results between the LALES and Baltimore Eye Survey may be related not only to their different populations, but also to their differing definitions of DM. Unlike in the LALES, the definition of DM in the Baltimore Eye Survey was limited to positive history of diabetes elicited from the patient during a personal interview.12 Proyecto VER studied a population similar to that of the LALES but found no association between primary OAG and a history of T2DM after adjusting for age.9 Although both studies had similar rates of T2DM, Proyecto VER found a lower prevalence of OAG (1.97%) than the LALES (4.74%). Although both studies were of Latino individuals, approximately 40% of the Proyecto VER participants had some Native American ancestry, compared with only 5.3% of LALES participants. These genetic and hereditary differences between the 2 populations of Proyecto VER and the LALES, along with differences in study design and recruitment methodology and variations in definitions of T2DM and OAG, may help explain the variability in reported results.

The Rotterdam Study7 had previously reported a positive association between DM and OAG, with a relative risk of 3.11 (95% CI, 1.12–8.66) of prevalent high-tension OAG in participants with DM using a subset of their baseline data. However, the authors changed their definition of OAG used in the baseline analysis (now excluding IOP as part of the diagnosis of OAG) for the subsequent longitudinal data analysis. Using the newer definition of OAG, the Rotterdam Study13 recently reported that diabetes was not a risk factor for incident OAG in their prospective population-based cohort study of whites. Furthermore, they reported that the recalculated relative risk of the baseline group in their final analysis had also become nonsignificant (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.96–2.03), based on their revised OAG definition. However, the Rotterdam Study had 99% non-Latino white participants, whereas the LALES includes Latinos mainly of Mexican ancestry. In addition, the prevalence of T2DM in the LALES population (19.6%) was significantly higher than that in the Rotterdam Study baseline group (7.9%).13 Differences between the Rotterdam and LALES sample populations, including demographics, variations in definitions, and prevalence rates of OAG and DM, may help to explain the disparate results between the 2 studies.

Despite these contradictory data, our results are remarkably similar to those of a recent meta-analysis of the association between DM and OAG (7 cross-sectional studies and 5 case–control studies), which reported that persons with DM had 1.5-fold greater odds of having OAG (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9; random effects model).21

In addition to our finding that the presence of T2DM is an independent risk factor for OAG in the LALES, we also found a higher risk of OAG with longer duration of T2DM. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first populationbased study to report this independent association between longer duration of DM and higher prevalence of OAG. Previously, the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy reported an increased incidence of glaucoma with longer duration of DM in younger and older persons.22 Although the NHS found a positive association between presence of T2DM and higher prevalence of OAG, it failed to confirm an association between longer duration of T2DM and OAG.10 The NHS authors reported that their study may have lacked the statistical power to detect a positive trend between T2DM duration and risk of OAG.

Diabetes is known to cause microvascular damage and may affect vascular autoregulation of the retina and optic nerve. Evidence demonstrates that vascular disturbances to the the optic nerve’s anterior portion are responsible for optic nerve head changes, which can result in glaucomatous optic neuropathy.23 In addition to altering vascular tissues, DM compromises glial and neuronal functions and metabolism in the retina, which can make retinal neurons including retinal ganglion cells more susceptible to glaucomatous damage.24 Furthermore, DM increases the susceptibility of retinal ganglion cells to additional stresses relating to OAG such as elevated IOP.25 It seems reasonable to consider that a longer duration of DM with a prolonged insult to the retina and optic nerve via vascular, glial, and neuronal factors would be associated with a higher risk of OAG.

Strengths of our study include that the diagnosis of glaucoma was based on optic disc and VF criteria, independent of IOP level. Furthermore, the risk of selection bias was largely eliminated, as this was a population survey with a high participation rate. However, as with most populationbased studies, one of the limitations was recall bias. This could play a role with regard to those participants assigned a diagnosis of DM based on self-reported history of treated DM, even though they had normal HbA1c and random blood glucose levels at the time of the LALES examination. A very small proportion of individuals had very high levels of HbA1c: 85.5% of participants had <7%, 7.7% of participants had ≥7% to 9%, and 6.8% of participants had ≥9%. Therefore, it seems less likely that very high HbA1c would be an explanation for the outcome of this study. In addition, because most properly treated diabetics would be expected to have controlled blood glucose, they would not be expected to have elevated HbA1c or random blood glucose levels. Furthermore, our results were essentially unchanged when the definition of DM was based on a history of treated DM alone, rather than our criteria of history of treated DM and/or laboratory-defined DM. In addition, our results were unchanged with the reanalysis performed after excluding all participants with history of DM treated by diet alone (without use of antidiabetic tablets or insulin, or with elevated blood sugar values). Furthermore, our results also remain unchanged when statistical analyses were performed after excluding all participants with any form of DR, as well as all participants with PDR. These additional analyses provide confidence in our conclusion that the presence of T2DM is an independent risk factor for OAG in adult Latinos.

In summary, the presence of T2DM and a longer duration of T2DM were found to be independently associated with a higher risk of OAG in the Latino population of the LALES. The relatively high prevalence of DM and OAG in this group presents enormous public health implications, especially considering that the Latino population is the largest and fastest growing minority in the U.S. Screening programs and health care planning may be impacted by this association found in the LALES between OAG and DM, likely with the need for additional testing for OAG. Finally, this current report is a step toward resolving the controversy regarding whether DM is a risk factor for OAG. Future longitudinal data should provide a more robust assessment of the risk of developing OAG in persons with T2DM.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (core grant no. EY03040); National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Bethesda, Maryland (grant no. EY11753); and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York (unrestricted grant). Dr Varma is a Research to Prevent Blindness Sybil B. Harrington Scholar.

Appendix

Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Rohit Varma, MD, MPH, Sylvia H. Paz, MS, Stanley P. Azen, PhD, Lupe Cisneros, COA, Elizabeth Corona, Carolina Cuestas, OD, Denise R. Globe, PhD, Sora Hahn, MD, Mei-Ying Lai, MS, George Martinez, Susan Preston-Martin, PhD, Ronald E. Smith, MD, LaVina Tetrow, Mina Torres, MS, Natalia Uribe, OD, Jennifer Wong, MPH, Joanne Wu, MPH, Myrna Zuniga.

Battelle Survey Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri

Sonia Chico, BS, Lisa John, MSW, Michael Preciado, BA, Karen Tucker, MA.

Ocular Epidemiology Grading Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

Ronald Klein, MD, MPH.

Footnotes

Presented in part at: Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting, May 2006, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in the article.

References

- 1.Quigley HA. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:389–93. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.5.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leske MC. The epidemiology of open-angle glaucoma: a review. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:166–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein BE, Klein R, Sponsel WE, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1499–504. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, et al. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma: the Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991;266:369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leske MC, Connell AM, Schachat AP, Hyman L. The Barbados Eye Study: prevalence of open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:821–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180121046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, Healey PR. Open-angle glaucoma and diabetes: the Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:712–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dielemans I, de Jong PT, Stolk R, et al. Primary open-angle glaucoma, intraocular pressure, and diabetes mellitus in the general elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1271–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le A, Mukesh BN, McCarty CA, Taylor HR. Risk factors associated with the incidence of open angle glaucoma: the Visual Impairment Project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3783–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, et al. The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of Hispanic participants: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1819–26. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.12.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasquale LR, Kang JH, Manson JE, et al. Prospective study of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of primary open-angle glaucoma in women. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1081–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1439–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tielsch JM, Katz J, Quigley HA, et al. Diabetes, intraocular pressure, and primary open-angle glaucoma in the Baltimore Eye Survey. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Voogd S, Ikram MK, Wolfs RC, et al. Is diabetes mellitus a risk factor for open angle glaucoma? The Rotterdam Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1827–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein BE, Klein R, Jensen SC. Open-angle glaucoma and older-onset diabetes: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1173–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed January 10, 2006];(NP-T5-G) projections of the resident population by race, Hispanic origin, and nativity: middle series, 2050–2070. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/summary/np-t5-g.txt.

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed April 26, 2007];Census 2000 demographic profile highlights: selected population group: Hispanic or Latino (of any race) Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFIteratedFacts?_event=&geo_id=01000US&_geoContext=01000US&_street=&_county=&_cityTown=&_state=&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=010&_submenuId=factsheet_2&ds_name=DEC_2000_SAFF&_ci_nbr=400&qr_name=DEC_2000_SAFF_R1010®=DEC_2000_SAFF_R1010%3A400&_keyword=&_industry=

- 17.U.S. Bureau of the Census . Current population reports. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995–2050. P25-1130. Bureau of the Census; Washington: [Accessed April 23, 2007]. 1996. pp. 1–2.pp. 13–14. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1130. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varma R, Paz SH, Azen SP, et al. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varma R, Torres M, Pena F, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in adult Latinos. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleveland WS, Grosse E. Computational methods for local regression. Stat Comput. 1991;1:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonovas S, Peponis V, Filioussi K. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for primary open-angle glaucoma: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2004;21:609–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Incidence of self reported glaucoma in people with diabetes mellitus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:743–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.9.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayreh SS. Pathogenesis of optic nerve damage and visual field deficits in glaucoma. In: Greve EL, editor. Glaucoma Symposium Diagnosis and Therapy, Amsterdam, September 1979, with Panel Discussions on Glaucoma and Cataract, Narrow Angles. Vol. 22. Kluwer; Boston: 1980. pp. 89–110. Documenta Ophthalmologica: Proceedings Series. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura M, Kanamori A, Negi A. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000081775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanamori A, Nakamura M, Mukuno H, et al. Diabetes has an additive effect on neural apoptosis in rat retina with chronically elevated intraocular pressure. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28:47–54. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.1.47.23487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]