Abstract

Purpose

To examine the association between health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and visual field (VF) loss in participants with open-angle glaucoma (OAG) in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES).

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Participants

Two hundred thirteen participants with OAG and 2821 participants without glaucoma or VF loss.

Methods

Participants in the LALES—a population-based prevalence study of eye disease in Latinos 40 years and older, residing in Los Angeles, California—underwent a detailed eye examination including an assessment of their VF using the Humphrey Automated Field Analyzer (Swedish interactive thresholding algorithm Standard 24-2). Open-angle glaucoma was determined by clinical examination. Mean deviation scores were used to assess severity of VF loss. Health-related QOL was assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) and 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25). Linear regression and analysis of covariance were used to assess the relationship between HRQOL scores and VF loss after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and visual acuity.

Main Outcome Measures

The 25-item NEI-VFQ and SF-12 scores.

Results

A trend of worse NEI-VFQ-25 scores for most subscales was observed with worse VF loss (using both monocular and calculated binocular data). Open-angle glaucoma participants with VF loss had lower scores than participants with no VF loss. This association was also present in participants who were previously undiagnosed and untreated for OAG (N = 160). Participants with any central VF loss had lower NEI-VFQ-25 scores than those with unilateral or bilateral peripheral VF loss. There was no significant impact of severity or location of VF loss on SF-12 scores.

Conclusion

Greater severity of VF loss in persons with OAG impacts vision-related QOL. This impact was present in persons who were previously unaware that they had glaucoma. Prevention of VF loss in persons with glaucoma is likely to reduce loss of vision-related QOL.

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of low vision and blindness in adults 40 years and older. It is expected that worldwide the prevalence of glaucoma and associated blindness will increase dramatically during the next 2 decades with the aging of the world population.1 By 2010, the number of people with open-angle glaucoma (OAG) is expected to exceed 44 million worldwide and 2.7 million in the United States.1 Glaucoma is a disease that causes damage to the optic nerve, resulting in loss of the peripheral visual field (VF) during early stages of the disease, progressing to central VF loss (VFL) in later stages. The impact of glaucoma and severity of VFL on general and vision-specific functioning has not been well described. A small number of studies of glaucoma patients have examined the relationship between VFL and vision-specific or health-related quality of life (HRQOL).2–5 Gutierrez et al2 found a steady linear decline between VFL and HRQOL in glaucoma patients (N = 147) using the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ), suggesting that prevention of early VFL may be critical for maintaining patient HRQOL. The magnitude of the association is not entirely clear, however, as other investigators have found only modest associations between VFL in glaucoma patients and vision-specific or general measures of HRQOL,4,5 and in these clinic-based samples, patient knowledge of their glaucoma and treatment status may have influenced their perception and reporting of HRQOL.

In the current analysis, we examined the association between severity of VFL and vision-specific HRQOL in adults with glaucoma participating in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES). The analyses were completed to investigate the degree of glaucomatous VFL necessary to observe meaningful differences in self-reported HRQOL. We also examined the types of daily activities that are most impacted by VFL and how location of VFL (unilateral peripheral, bilateral peripheral, any central) impacts HRQOL. We used the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) to assess general health and the 25-item NEI-VFQ (NEI-VFQ-25) to examine vision-specific HRQOL. Our population-based sample included a large number of adults without previous knowledge of their glaucoma status, which allowed us to explore the impact of knowledge of glaucoma or treatment status on the association between self-reported HRQOL and VFL.

Materials and Methods

Data for this analysis were collected as part of the LALES, a population-based prevalence study of eye disease in Latinos living in Los Angeles, California and 40 years or older. Details of the study design and data collected have been described previously.6 Briefly, a census of all residential households in 6 census tracts in La Puente, California was completed to identify individuals eligible to be included in the study. Eligibility included men and women 40 or older who were Latinos (self-described) and resided in any of the 6 census tracts. Eligible participants were given a verbal and written description of the study and invited to participate in both a home interview and a clinic examination between February 2000 and May 2003. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of participants were similar to those of the Latino population in the U.S.6 All study procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Institutional review board/ethics committee approval was obtained from the Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

A brief home interview was completed after informed consent was obtained that included information on demographics, history of ocular and medical conditions, access to health care, health insurance coverage for eye care, and degree of acculturation.7 Operational definitions for these variables were similar to those described in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.8,9 Twelve self-reported medical conditions were measured using a systematic comorbidity summation score including diabetes mellitus, arthritis, stroke or brain hemorrhage, high blood pressure, angina, heart attack, heart failure, asthma, skin cancer, other cancers, back problems, and deafness or hearing problems.10–12 Acculturation was measured using the short-form Cuellar Acculturation Scale,9 with scores ranging from 1 to 5 (5 representing the highest level of acculturation).9

Open-angle Glaucoma

Open-angle glaucoma was determined by clinical examination after the completion of the study interview. Visual field test results and optic disc photographs were independently reviewed by 2 glaucoma specialists. Intraocular pressure was not considered in the definition of glaucoma. A more detailed description of the methodology for determining glaucoma status has been presented.12

Visual Field Testing

Visual field was measured in each eye using the Humphrey Field Analyzer II (Swedish interactive thresholding algorithm Standard 24-2 program) (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA). Visual field testing was repeated for any abnormal results; results of the second test were recorded and confirmed by 2 ophthalmologists. Mean deviation (MD) scores were used to assess severity of VFL both as a continuous variable and as a dichotomous variable: no VFL (MD > −2 decibels [dB]) and VFL (MD ≤ −2 dB). An MD > −2 dB was selected to maximize the probability that individuals categorized as having VFL had actual glaucomatous VFL. Binocular VF scores were calculated from monocular data using 2 different probability summation models (probability summation 2 and probability summation 4).13,14 The location of VFL was determined by review of perimetry data by 2 glaucoma specialists (unilateral peripheral, bilateral peripheral, or both central and peripheral).

Visual Acuity Testing

The procedure used to measure presenting distance visual acuity (VA) in the LALES has been described previously.15–17 Presenting distance VA for each LALES participant was measured with the presenting correction (if any) at 4 m using modified Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study distance charts transilluminated with a chart illuminator (Precision Vision, La Salle, IL). Presenting VA was scored as the total number of lines read correctly and converted to a logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution score. Visual acuity loss was defined as presenting VA 20/40 or worse.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Interviewers administered the questionnaires (before the clinical examination) in either English or Spanish according to participant preference at the LALES Local Eye Examination Center.

12-Item Short-Form Health Survey

General HRQOL was measured using the SF-12 (version 1),18 data from which was used to calculate the standard U.S. norm-based SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores. Higher PCS and MCS scores represent better HRQOL.19

25-Item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire

Vision-related HRQOL was assessed by the NEI-VFQ-25,20,21 which was designed to measure the dimensions of self-reported vision-targeted health status that are important for persons with chronic eye diseases.20 The survey measures the influence of visual disability and visual symptoms on generic health domains such as emotional well-being and social functioning, in addition to task-oriented domains related to daily visual functioning.20,21 The survey is composed of 12 scales: general health, general vision, near and distance vision activities, ocular pain, vision-related social function, vision-related role function, vision-related mental health, vision-related dependency, driving difficulties, color vision, and peripheral vision. The NEI-VFQ-25 also includes a general health item similar to one of the SF-12 items. Each subscale consisted of a minimum of 1 item and maximum of 4 items. The standard algorithm was used to calculate the scale scores, which have a possible range from 0 to 100. A higher score represents better visual functioning and well-being. Eleven of the 12 scale scores (excluding the general health item) were averaged to yield a composite score.20

Statistical Analyses

Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous demographic characteristics by glaucoma status with means and standard deviations (SDs) presented for age (years), acculturation scores, and number of comorbidities. Tukey pairwise comparisons were used to identify significant differences across subgroups of glaucoma and VFL. Categorical variables (unemployed [yes/no], income≤$20 000 [yes/no], education [less than high school, high school graduate, college training or higher], health insurance [yes/no], vision insurance [yes/no], VA loss [yes/no]) are presented as frequencies and percents; differences across subgroups were compared using chi-square tests. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were conducted at the 0.05 level for the categorical variables. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.1, SAS, Inc., Cary, NC).

Analysis of covariance was used to compare the SF-12 PCS and MCS and NEI-VFQ-25 subscale and composite scores by glaucoma status. Models were adjusted for age, gender, education, employment status, income, acculturation, health insurance, vision insurance, number of comorbidities, knowledge of glaucoma status at time of HRQOL questionnaire, and VA.22

Because of the skewed score distribution toward the higher scores, a logarithmic transformation was performed to normalize the distribution using the formula tSCORE = ln(101 – SCORE), in which tSCORE and SCORE are the transformed and untransformed values of the NEI-VFQ-25 scales, respectively. If significant differences were found, Tukey multiple comparison23,24 tests for adjusting the overall significance level were used to identify significant pairwise differences in the logarithmically transformed scale and composite scores. For ease of interpretation, however, results are reported in the original untransformed scale.

Predicted mean SF-12 and NEI-VFQ-25 scores were plotted against MD for the worse eye, MD for the better eye, and calculated binocular vision. The plotted figures show means for each unit of MD (in decibels) from 0 to −30 dB for monocular data (data for binocular data not shown). Predicted mean SF-12 and NEI-VFQ-25 scores were calculated for continuous MD values adjusting for the 11 covariates. Stratified analyses by knowledge of glaucoma diagnosis at the time of the HRQOL interview and treatment history were also completed to evaluate potential effect modification. Linear regression β-coefficients were calculated for the association between VFL (MD score in decibels) and HRQOL (NEI-VFQ-25 and SF-12). To examine possible nonlinear relationships between HRQOL measures and VFL, an iterative locally weighted least-squares method was used to generate lines of best fit (locally weighted least squares fit line) using S-Plus 7.0 (Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA).25

Effect sizes (ESs) were calculated to measure the magnitude of location-specific VFL on HRQOL. Effect sizes were calculated as the difference in the mean covariate-adjusted HRQOL scores (comparing participants with location-specific VFL to those with no VFL) divided by the SD of the scores for the no VFL group.26 Effect sizes of 0.20 to 0.49 are considered small; 0.50 to 0.79, moderate; and ≥0.80, large.27

Results

Description of Study Cohort

A total of 7789 participants were identified as eligible for LALES; of these, 82% (6357) completed the ophthalmic examination and 291 were identified with OAG. Of the original 291 OAG participtants, 73 were excluded because they had VFL in the nonglaucomatous eye (19), had no measure of VF (6), did not answer the question on history of glaucoma (5), or did not complete the NEI-VFQ-25 (48), leaving 213 (73%) of all identified OAG participants available for inclusion in the analyses. Characteristics of glaucoma cases are shown in Table 1 (available at http://aaojournal.org). The mean age of the glaucoma cases was 65.6 years (range, 40–93). Cases were more likely to have health insurance (75%), vision insurance (61%), and less than a high school education (73%) than participants without glaucoma. In this sample, 26% of glaucoma cases had diabetes. Of the participants with glaucoma, 30 (17%) had no VFL, 46 (27%) had unilateral peripheral VFL, 52 (30%) had bilateral peripheral VFL, and 44 (26%) had any central VFL. Demographics of the subjects excluded for missing data did not substantially differ from those included in the analyses.

Table 1.

Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Participants’ Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Stratified by Open-angle Glaucoma (OAG) Status and Visual Field Loss (VFL) Status

|

Sociodemographic and Clinical

Characteristics |

No OAG, No VFL

(N = 2821) |

OAG

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No VFL (N = 33) | VFL (N = 180) | P Value * | ||

| Age | 52.2 (8.9)† | 62.1 (9.5)‡ | 66.3 (11.7)§ | <0.0001 |

| Acculturation score∥ | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.9)† | 0.16 |

| Comorbidities¶ | 1.3 (1.4)† | 1.9 (1.6)‡ | 2.3 (2.0)‡ | <0.0001 |

| Gender (female) | 1572 (55.7) | 15 (45.5) | 92 (51.1) | 0.16 |

| Unemployed | 1169 (41.6)† | 22 (66.7)‡ | 136 (75.6)‡ | <0.0001 |

| Income≤$20 000 | 1153 (40.9)† | 19 (57.6)† | 86 (47.8)† | 0.03 |

| Education < 12 yrs | 1705 (60.7)† | 23 (69.7)†‡ | 133 (73.9)‡ | 0.0003 |

| Health insurance (yes) | 1841 (65.5)† | 28 (84.9)‡ | 132 (73.3)†‡ | 0.01 |

| Vision insurance (yes) | 1413 (50.8)† | 25 (78.1)‡ | 103 (57.9)†‡ | 0.02 |

| Visual acuity loss# (none) | 2533 (89.8)† | 29 (87.9)† | 94 (52.2)‡ | <0.0001 |

Data presented as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables (age, acculturation score, comorbidities); categorical variables are presented as frequency counts with percents of individuals in severity of visual field loss category.

Based on analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables (with Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons).

For each row, means and percentages with different symbols statistically significantly differ from one another (P<0.05).

For each row, means and percentages with different symbols statistically significantly differ from one another (P<0.05).

For each row, means and percentages with different symbols statistically significantly differ from one another (P<0.05).

Measured using the short-form Cuellar Acculturation Scale.

No. of self-reported comorbidities (diabetes, arthritis, stroke/brain hemorrhage, high blood pressure, angina, heart attack, heart failure, asthma, skin cancer, other cancer, back problems, hearing problems, and other major health problems).

Defined as presenting visual acuity of 20/40 or worse.

Of the 213 glaucoma cases, 160 (75%) were diagnosed with glaucoma for the first time during the LALES clinical eye examination. Therefore, these participants were unaware of their glaucoma status at the time they completed the HRQOL questionnaire with the study interviewer. Of the 53 glaucoma patients with a history of glaucoma at the time of enrollment in LALES, 40 (75%) reported receiving treatment for glaucoma. The VF MD scores for the glaucoma cases newly diagnosed at LALES were −4.3 and −8.7 dB in the better seeing and worse seeing eyes, respectively. The VF MD scores for the 53 glaucoma cases with a history of glaucoma before enrolling in LALES were lower (i.e., worse) (−7.6 for the better seeing eye and −13.1 for the worse seeing eye).

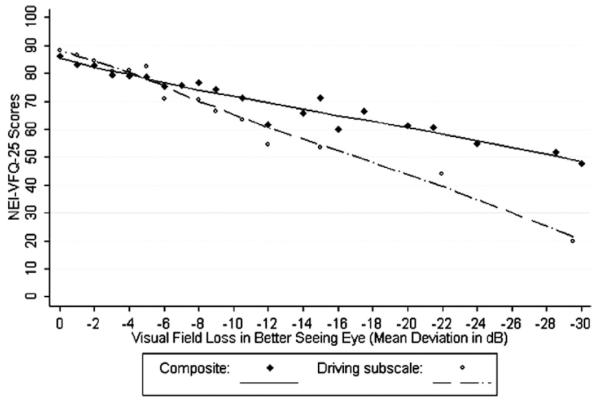

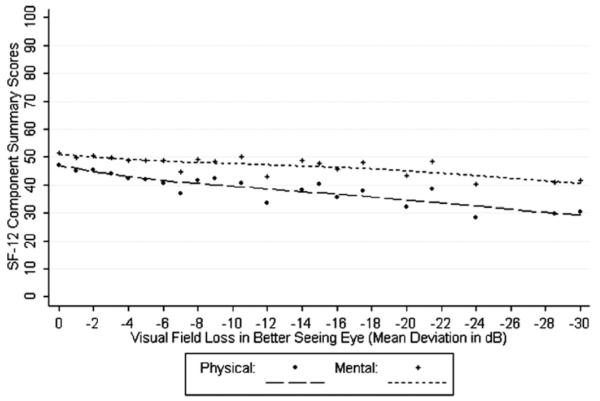

Relationship between the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire, 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey, and Mean Deviation of the Better or Worse Seeing Eye. A monotonic trend was observed between VFL and most NEIVFQ-25 subscale scores, such that as VFL worsened, the QOL scores worsened. Linear regression β-coefficients for the association between VFL (MD score in decibels) and adjusted mean NEI-VFQ-25 and SF-12 scores are shown in Table 2 for both the better seeing and worse seeing eyes. β-coefficients for both the SF-12 and NEI-VFQ were slightly diminished after adjusting for knowledge of glaucoma history and treatment status. β-coefficients based on data from the better seeing eyes were statistically significant for 6 of 12 NEI-VFQ subscales and the NEI-VFQ composite score. Persons with VFL had the greatest difficulty with driving activities and dependency. A 3-dB difference in VFL was associated with an approximately 5-point difference in the NEI-VFQ driving subscale. The β-coefficients for associations between VFL and the SF-12 MCS and PCS were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Linear Regression β-Coefficients for the Association between Visual Field Loss (VFL; Mean Deviation Score [Decibels]) and Health-Related Quality of Life in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Participants with Glaucoma (N = 213), Stratified by VFL in Better Seeing and Worse Seeing Eyes

|

VFL in Better Seeing Eye

|

VFL in Worse Seeing Eye

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-Related Quality-of-Life Measures | β Coefficient | P Value | β Coefficient | P Value |

| SF-12 | ||||

| MCS | 0.28 (−0.01 to 0.56) | 0.056 | 0.03 (−0.19 to 0.24) | 0.800 |

| PCS | 0.16 (−0.05 to 0.38) | 0.128 | 0.02 (−0.14 to 0.18) | 0.802 |

| NEI-VFQ-25 | ||||

| General health | 0.32 (−0.22 to 0.86) | 0.251 | 0.17 (−0.24 to 0.57) | 0.422 |

| Color vision | 0.65 (0.16–1.15) | 0.01 | 0.16 (−0.21 to 0.54) | 0.400 |

| Driving difficulties* | 1.50 (0.69–2.31) | 0.0004 | 0.86 (0.31–1.40) | 0.002 |

| Distance vision | 0.46 (−0.01 to 0.93) | 0.053 | 0.21 (−0.14 to 0.56) | 0.241 |

| Near vision | 0.59 (0.10–1.08) | 0.018 | 0.23 (−0.14 to 0.60) | 0.213 |

| Vision-related dependency | 1.14 (0.54–1.74) | 0.0002 | 0.71 (0.25–1.16) | 0.003 |

| General vision | 0.35 (−0.04 to 0.74) | 0.081 | −0.05 (−0.35 to 0.24) | 0.722 |

| Vision-related mental health | 0.70 (0.13–1.27) | 0.017 | 0.53 (0.11–0.96) | 0.015 |

| Ocular pain | 0.47 (−0.10 to 1.05) | 0.108 | 0.12 (−0.31 to 0.56) | 0.584 |

| Peripheral vision | −0.01 (−0.58,0.56) | 0.967 | 0.34 (−0.09 to 0.77) | 0.116 |

| Vision-related role function | 0.73 (0.13–1.33) | 0.018 | 0.34 (−0.12 to 0.79) | 0.147 |

| Vision-related social function | 0.07 (−0.35 to 0.48) | 0.745 | −0.11 (−0.42 to 0.21) | 0.507 |

| Composite† | 0.53 (0.16–0.91) | 0.01 | 0.27 (−0.02 to 0.56) | 0.065 |

MCS = Mental Component Summary; NEI-VFQ-25 = 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire; PCS = Physical Component Summary; SF-12 = Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey.

Data presented as coefficients (95% confidence interval). The linear regression models were adjusted for the 11 covariates.

Scores could be calculated for 122 participants who reported that they were currently driving or had driven.

Unweighted mean of the 12 subscale scores (except general health).

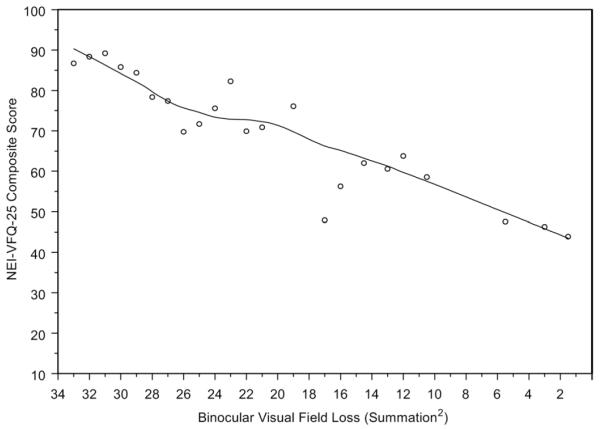

Figure 1 shows the locally weighted least squares plots for VFL and adjusted means for the NEI-VFQ composite and driving subscales. Figure 2 shows the locally weighted least squares plots for adjusted mean SF-12 scores (PCS and MCS) by VFL in the better seeing eye adjusted for covariates. A plot of the adjusted mean NEI-VFQ composite scores by binocular VFL is shown in Figure 3 (probability summation 2 is shown; the plot for probability summation 4 was similar). β-coefficients and plots for binocular data were based on 132 glaucoma patients with complete data available for probability summation calculations. When restricting to the same 132 glaucoma patients, linear regression β-coefficients for the association between NEI-VFQ composite and subscale scores and monocular VFL in the better seeing eye were similar to those for binocular VFL, whereas coefficients for monocular VFL in the worse seeing eye were generally smaller.

Figure 1.

Locally weighted least squares plot of the relationship of predicted 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) composite scores and the driving subscale score (adjusted for covariates) by visual field loss in the better seeing eyes of participants with open-angle glaucoma in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. dB = decibels.

Figure 2.

Locally weighted least squares plot of the relationship of predicted 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) Physical Component Summary Scores and Mental Component Summary Scores (adjusted for covariates) by visual field loss in the better seeing eyes of participants with open-angle glaucoma in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. dB = decibels.

Figure 3.

Locally weighted least squares plot of the relationship of predicted 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25) composite scores (adjusted for covariates) and calculated binocular visual field loss (VFL) (probability summation of data from the two eyes was used to compute a single binocular VFL score) of participants with open-angle glaucoma in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study.

Relationship of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire and 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey with Glaucoma, by Status of Visual Field Loss. Of the 213 participants with glaucoma, 180 were classified as having VFL (MD < −2 dB). Adjusted mean NEI-VFQ and SF-12 scores were generally lower for participants with glaucomatous VFL than for glaucoma participants without VFL (N = 33) or LALES participants without glaucoma or VFL (N = 2821) (Table 3). Participants with glaucomatous VFL had significantly lower SF-12 PCS mean scores than participants without glaucoma; however, this difference was not statistically significant for the SF-12 MCS. Peripheral vision, vision-related dependency, and the composite score were significantly lower for participants with glaucomatous VFL than for participants without glaucoma or VFL after adjusting for covariates. The differences in HRQOL scores by VFL status persisted after adjusting for a history of glaucoma (as shown in Table 3) or when excluding individuals with a history of glaucoma and/or treatment history from the analyses.

Table 3.

Analysis of Covariance Assessing the Relationship between Health-Related Quality-of-Life Measures and Glaucoma Status in the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (N = 3034)

|

Glaucoma

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Health-Related Quality-of-Life Measures

[Adjusted Mean Scores (SD)] |

No OAG, No VFL

(N = 2821) |

No VFL (MD Better

than −2 dB) (N = 33) |

VFL (MD Worse than −2 dB)

(N = 180) |

P Value |

| SF12 | ||||

| MCS | 49.2 (0.8) | 48.7 (1.9) | 48.6 (0.9) | 0.85 |

| PCS | 46.2 (0.7)* | 47.0 (1.5)* | 44.1 (0.7)† | 0.03 |

| NEI-VFQ-25 | ||||

| General health | 46.3 (1.7) | 43.9 (3.9) | 47.2 (1.9) | 0.68 |

| Color vision | 89.5 (1.1) | 91.1 (2.5) | 88.3 (1.2) | 0.99 |

| Driving difficulties‡ | 75.4 (1.4) | 72.0 (3.2) | 70.6 (1.6) | 0.61 |

| Distance vision | 75.6 (1.2) | 79.4 (2.8) | 72.1 (1.4) | 0.11 |

| Near vision | 73.2 (1.5) | 77.7 (3.4) | 70.8 (1.7) | 0.21 |

| Vision-related dependency | 80.2 (1.3)* | 84.8 (3.0)* | 73.4 (1.5)† | 0.046 |

| General vision | 61.9 (1.3) | 62.5 (2.9) | 59.3 (1.4) | 0.54 |

| Vision-related mental health | 67.0 (1.5) | 69.2 (3.5) | 61.9 (1.7) | 0.15 |

| Ocular pain | 73.5 (1.5) | 74.1 (3.5) | 69.7 (1.7) | 0.37 |

| Peripheral vision | 81.6 (1.5)* | 86.7 (3.3)* | 77.5 (1.6)† | 0.01 |

| Vision-related role function | 80.4 (1.5) | 88.1 (3.3) | 76.8 (1.6) | 0.08 |

| Vision-related social function | 87.0 (1.0) | 88.2 (2.2) | 86.2 (1.1) | 0.99 |

| Composite§ | 76.8 (0.9)* | 79.7 (2.1)* | 73.2 (1.0)† | 0.02 |

dB = decibels; MD = mean deviation; MCS = Mental Component Summary; NEI-VFQ-25 = 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire; OAG = open-angle glaucoma; PCS = Physical Component Summary; SD = standard deviation; SF-12 = Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short-Form Health Survey; VFL = visual field loss.

Data presented as mean (standard deviation). The SF-12 and NEI-VFQ-25 scores were adjusted for the 11 covariates.

For each row, means with different symbols statistically significantly differ from one another.

For each row, means with different symbols statistically significantly differ from one another.

Scores could be generated for 2255 (no glaucoma and VFL), 21 (glaucoma, no VFL), and 101 (glaucoma with VFL) of the participants who reported that they were currently driving or had driven.

Unweighted mean of the 12 subscale scores (except general health).

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire and 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey Effect Size Estimates by location of Visual Field Loss. Glaucoma participants with any central VFL had lower HRQOL scores than individuals with no VFL. Large effects were found for the NEI-VFQ composite scale (ES = 1.09) as well as 4 subscales: vision-related role function (ES = 1.74), driving difficulties (ES = 1.17), vision-related dependency (ES = 0.89), and peripheral vision (ES = 0.83). Small effects were found for the SF-12 MCS and PCS when comparing glaucoma participants with any central VFL with those with no VFL. When comparing NEI-VFQ and SF-12 scores for glaucoma cases with bilateral peripheral VFL and glaucoma cases with no VFL, moderate effects were observed for the composite scale (ES = 0.75) as well as peripheral vision (ES = 0.62), distance vision (ES = 0.61), and driving difficulties (ES = 0.59); large effects were found for vision-specific dependency (ES = 0.94) and vision-related role function (ES = 0.89). Effect sizes were small for glaucoma participants with unilateral peripheral VFL compared with those with no VFL, with the exception of a moderate effect for vision-related role function (ES = 0.71).

Discussion

In the LALES population, we found that loss of VF among glaucoma participants was associated with worse NEIVFQ-25 and SF-12 PCS scores. A monotonic trend was observed between VFL and most NEI-VFQ-25 subscale scores, such that glaucoma cases with severe VFL had lower QOL scores than participants with no VFL. This pattern was present when using monocular (better seeing or worse seeing eyes) or calculated binocular data. These findings suggest that adults with glaucoma experience a measurable loss in HRQOL early in the disease process and that prevention of small or early changes in VFL can have important HRQOL benefits for adults with glaucoma.

A unique feature of our population-based sample was our ability to measure self-reported HRQOL, before the participants were diagnosed and therefore aware of their glaucoma status. The high proportion of adults (75%) in the LALES who were unaware that they had glaucoma at the time of enrollment in the study allowed us to measure the association between self-reported NEI-VFQ and SF-12 HRQOL and VFL independent of participants’ knowledge of glaucoma or treatment status. The associations between HRQOL and VF scores persisted even after controlling for knowledge of glaucoma or treatment status as indicator variables in the multivariable analyses, or when restricting to LALES participants that were unaware they had glaucoma at the time of their interview.

A small set of clinical studies previously reported on the impact of glaucoma on HRQOL. Similar to our findings in the LALES, Gutierrez et al2 found that VFL in the better seeing eye was associated with lower NEI-VFQ and the SF-36 scores and reported a linear association between VFL and NEI-VFQ scores. These data support the finding that vision-specific QOL begins to decline with mild VFL and continues to decline with increasing severity of VFL. Parrish et al5 found only moderate correlations between binocular VFL using the Esterman binocular VF testing score and the NEI-VFQ, and Noe et al4 found no association between Esterman binocular VF testing scores and HRQOL using the Impact of Vision Impairment Questionnaire. Measures of binocular VFL are assumed to be more representative of true vision than monocular; however, Jampel’s work indicates that correlations between all VF test scores (e.g., monocular better seeing eye, monocular worse seeing eye, Esterman binocular) and vision-specific HRQOL are modest overall.28 In the LALES, correlation coefficients between NEI-VFQ scores and monocular VFL (better eye) and calculated binocular VFL were similar. Investigators found weak correlations between the Visual Activities Questionnaire and VFL of glaucoma cases at enrollment in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study.3,29 Sherwood et al30 and Wilson et al,31 using general health measures of HRQOL, found that glaucoma cases had lower SF-20 or SF-36 scores than controls.30,31

Persons with glaucomatous VFL had the greatest difficulty with driving activities. Other investigators also have found the greatest impact of glaucomatous VFL on measures of mobility or driving difficulty. Gutierrez et al2 found that glaucoma patients with VFL (better eye) had poorer NEI-VFQ scores for 7 of 11 subscales, of which the strongest correlation was found for driving difficulty. Parrish et al5 found only modest correlation between the NEI-VFQ driving difficulty subscale and Esterman binocular VF testing scores. In a cohort of 2520 older adults, Freeman et al found that general VFL was associated with reduced driving mileage and cessation of night driving.32 One explanation for the association between VFL and driving difficulties may be limitations in glare and dark adaptation, as light scatter has been shown to exaggerate VFL in glaucoma patients.33 In a group of 47 glaucoma patients, Nelson et al34 found that severity of VFL was significantly associated with glare and dark adaptation, and in an earlier study of 63 glaucoma patients, 70% of patients reported problems with glare; 54%, problems with adaptation to different levels of lighting; and 52%, problems with driving at night.35 Problems with bright lights, adaptation between light and dark, blurred vision, and seeing in the dark were frequent visual symptoms reported in a randomized clinical trial of approximately 600 newly diagnosed glaucoma patients.29

After driving, vision-related dependency was the next NEI-VFQ subscale most impacted by glaucomatous VFL. In a clinical study of age-related maculopathy, patients who were seeking low vision rehabilitation36 had NEI-VFQ scores lower than those of other low vision patients. Specifically, deficits were noted for role functioning, dependency, and mental health, as well as social functioning, near vision, and distance vision. The authors also found that patients who used low vision aids had higher NEI-VFQ scores than those without treatment,36 suggesting that the NEI-VFQ psychosocial subscales are sensitive to changes in vision of low vision patients.

In the LALES, we found that mean NEI-VFQ composite and subscale scores differed by location of glaucomatous VFL. Large effects were most frequently found for participants with central or central and peripheral VFL, whereas moderate to large effects were found for 5 of 12 NEI-VFQ subscales and the composite score for participants with bilateral peripheral VFL; small effects were found for 11 of 12 NEI-VFQ subscales and the composite score for individuals with unilateral peripheral VFL versus no VFL. The lower HRQOL scores for glaucoma participants with any central VFL fit with the disease course progressing from peripheral VFL in early stages of the disease to central and peripheral VFL in more advanced stages of the disease. The clinical implication of these findings is that early treatment of glaucoma is necessary to prevent loss of vision-specific QOL and that continued rigorous management of glaucoma is necessary to prevent a worsening of HRQOL.

In a previous LALES study of HRQOL and VFL due to any cause, we found losses in HRQOL scores with small changes in MD; HRQOL scores continued to decrease in an approximately linear relationship with MD scores for values between 0 and −30 dB.37 The largest associations between VFL from any cause and HRQOL subscales for the better seeing eye were observed for driving difficulties, followed by vision-specific dependency and vision-specific mental health. Associations between HRQOL and VFL due to any cause or due to glaucoma were similar with respect to the NEI-VFQ scales that were most sensitive to VFL (driving difficulties, vision-specific dependency). The domains of NEI-VFQ that are affected most will be influenced by the location of VFL. In glaucoma patients, this will largely be individuals with peripheral VFL. In cases of VFL due to other causes, the proportion of individuals with peripheral or central VFL may be quite different, and therefore, the impact on HRQOL may differ.

Although our study includes measures of VA and VF, a limitation of our analysis is that we do not have other measures of visual function such as contrast sensitivity or glare sensitivity, which would be useful in further investigating our findings with HRQOL, especially driving difficulties. Our conclusions are limited by the use of prevalent data, however, longitudinal data are currently being collected for the LALES.

The number of people with vision loss or blindness due to glaucoma will grow in the next 2 decades as the proportion of adults in the oldest population age groups continue to increase in the U.S. and worldwide. In the LALES, we found that glaucomatous VFL was associated with lower HRQOL scores, even at modest levels of vision loss. Because a large proportion of our population-based sample did not know that they had glaucoma at the time they completed the HRQOL questionnaire, we were able to assess the association between self-reported HRQOL and glaucomatous VFL, independent of participants’ knowledge of glaucoma or treatment status. The largest impact of VFL on HRQOL was seen for patients with any central VFL that may represent (1) cases with more advanced disease and (2) cases with VFL in a greater proportion of their VF. These findings suggest that adults with glaucoma experience real, measurable loss in HRQOL early in the disease process and that prevention of small or early changes in VFL can have important HRQOL benefits for glaucoma cases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (no. NEI U10 EY-11753), and National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (no. EY-03040).

Appendix

Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Rohit Varma, MD, MPH, Sylvia H. Paz, MS, Stanley P. Azen, PhD, Lupe Cisneros, COA, Elizabeth Corona, Carolina Cuestas, OD, Denise R. Globe, PhD, Sora Hahn, MD, Mei-Ying Lai, MS, George Martinez, Susan Preston-Martin, PhD, Ronald E. Smith, MD, LaVina Tetrow, Mina Torres, MS, Natalia Uribe, OD, Jennifer Wong, MPH, Joanne Wu, MPH, Myrna Zuniga.

Battelle Survey Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri

Sonia Chico, BS, Lisa John, MSW, Michael Preciado, BA, Karen Tucker, MA.

Ocular Epidemiology Grading Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

Ronald Klein, MD, MPH.

Footnotes

No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez P, Wilson MR, Johnson C, et al. Influence of glaucomatous visual field loss on health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:777–84. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150779014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills RP. Correlation of quality of life with clinical symptoms and signs at the time of glaucoma diagnosis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1998;96:753–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noe G, Ferraro J, Lamoureux E, et al. Associations between glaucomatous visual field loss and participation in activities of daily living. Clin Experimental Ophthalmol. 2003;31:482–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2003.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parrish RK, II, Gedde SJ, Scott IU, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1447–55. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160617016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma R, Paz SH, Azen SP, et al. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Globe DR, Schoua-Glusberg A, Paz S, et al. Using focus groups to develop a culturally sensitive methodology for epidemiological surveys in a Latino population: findings from the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES) Ethn Dis. 2002;12:259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: findings from HHANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(suppl):11–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks G, Garcia M, Solis JM. Health risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States: findings from HHANES, 1982–84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(suppl):20–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brody BL, Gamst AC, Williams RA, et al. Depression, visual acuity, comorbidity, and disability associated with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1893–900. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00754-0. discussion 1900–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Globe DR, Varma R, Torres M, et al. Self-reported comorbidities and visual function in a population-based study: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:815–21. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson-Quigg JM, Cello K, Johnson CA. Predicting binocular visual field sensitivity from monocular visual field results. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2212–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan F, Swanson WH. A cortical pooling model of spatial summation for perimetric stimuli. J Vis. 2006;6:1159–71. doi: 10.1167/6.11.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azen SP, Varma R, Preston-Martin S, et al. Binocular visual acuity summation and inhibition in an ocular epidemiological study: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1742–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma R, Fraser-Bell S, Tan S, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Latinos. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1288–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varma R, Torres M, Pena F, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in adult Latinos. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 2nd ed Health Institute; Boston: 1995. pp. 21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1050–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Pitts J, et al. Psychometric properties of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ) Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:1496–504. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.11.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Globe DR, Wu J, Azen SP, et al. The impact of visual impairment on self-reported visual functioning in Latinos. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu JC, Nelson B. Multiple comparisons in the general linear model. J Comput Graph Stat. 1998;7:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu JC. Multiple Comparisons: Theory and Methods. Chapman & Hall; London: 1996. p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleveland WS, Grosse E. Computational methods for local regression. Stat Comput. 1991;1:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenthal R. Parametric measures of effect size. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1994. pp. 231–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jampel HD. Glaucoma patients’ assessment of their visual function and quality of life. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2001;99:301–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janz NK, Wren PA, Lichter PR, et al. Quality of life in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients: the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:887–97. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00624-2. discussion 898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherwood MB, Garcia-Siekavizza A, Meltzer MI, et al. Glaucoma’s impact on quality of life and its relation to clinical indicators: a pilot study. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:561–6. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)93043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson MR, Coleman AL, Yu F, et al. Functional status and well-being in patients with glaucoma as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 questionnaire. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2112–6. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freeman EE, Munoz B, Turano KA, West SK. Measures of visual function and their association with driving modification in older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:514–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dengler-Harles M, Wild JM, Cole MD, et al. The influence of forward light scatter on the visual field indices in glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990;228:326–31. doi: 10.1007/BF00920056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson P, Aspinall P, Papasouliotis O, et al. Quality of life in glaucoma and its relationship with visual function. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:139–50. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson P, Aspinall P, O’Brien C. Patients’ perception of visual impairment in glaucoma: a pilot study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:546–52. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.5.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scilley K, DeCarlo DK, Wells J, Owsley C. Vision-specific health-related quality of life in age-related maculopathy patients presenting for low vision services. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:131–46. doi: 10.1076/opep.11.2.131.28159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKean-Cowdin R, Varma R, Wu J, et al. Severity of visual field loss and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:1013–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]