Abstract

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an important greenhouse gas, but large uncertainties remain in global budgets. Mangroves are thought to be a source of N2O to the atmosphere in spite of the limited available data. Here we report high resolution time series observations in pristine Australian mangroves along a broad latitudinal gradient to assess the potential role of mangroves in global N2O budgets. Surprisingly, five out of six creeks were under-saturated in dissolved N2O, demonstrating mangrove creek waters were a sink for atmospheric N2O. Air-water flux estimates showed an uptake of 1.52 ± 0.17 μmol m−2 d−1, while an independent mass balance revealed an average sink of 1.05 ± 0.59 μmol m−2 d−1. If these results can be upscaled to the global mangrove area, the N2O sink (~2.0 × 108 mol yr−1) would offset ~6% of the estimated global riverine N2O source. Our observations contrast previous estimates based on soil fluxes or mangrove waters influenced by upstream freshwater inputs. We suggest that the lack of available nitrogen in pristine mangroves favours N2O consumption. Widespread and growing coastal eutrophication may change mangrove waters from a sink to a source of N2O to the atmosphere, representing a positive feedback to climate change.

Nitrous oxide is a long lived greenhouse gas with an atmospheric lifetime of 118–131 years1, a global warming potential about 300 times that of CO2, and it is the major contributor to ozone destruction in the stratosphere2. Microbial processes within soils and surface waters produce most atmospheric N2O through nitrification and denitrification. The largest portion of global denitrification from natural sources is thought to occur within coastal waters (~45%)3, with these areas considered globally significant N2O sources4. However global estimates lack empirical data from some key environments such as mangrove waterways.

Mangrove forests cover about 138,000 km2 of coastline and are recognised to contribute disproportionally to global biogeochemical cycles5. Mangrove ecosystems are thought to be an important atmospheric N2O source6,7,8. Yet, N2O observations in mangroves are highly variable and often focus on soil emissions from eutrophic systems influenced by freshwater inputs9,10. The methodology typically used to estimate soil emissions (i.e. soil chambers) only captures N2O fluxes from exposed soils. To date, little work has been done on the rates of N2O exchange between surface waters and the atmosphere in mangroves. One study revealed high dissolved N2O concentrations, and suggested mangroves were a significant source of N2O to the atmosphere11. This study was undertaken over two 24-h periods in a mangrove tidal creek influenced by upstream freshwater inputs. However, because rivers are often enriched in N2O12, upstream riverine inputs of N2O may lead to a misinterpretation of the N2O source. As a result, it is unclear whether high dissolved N2O was related to upstream freshwater inputs or N2O production within the mangrove forest.

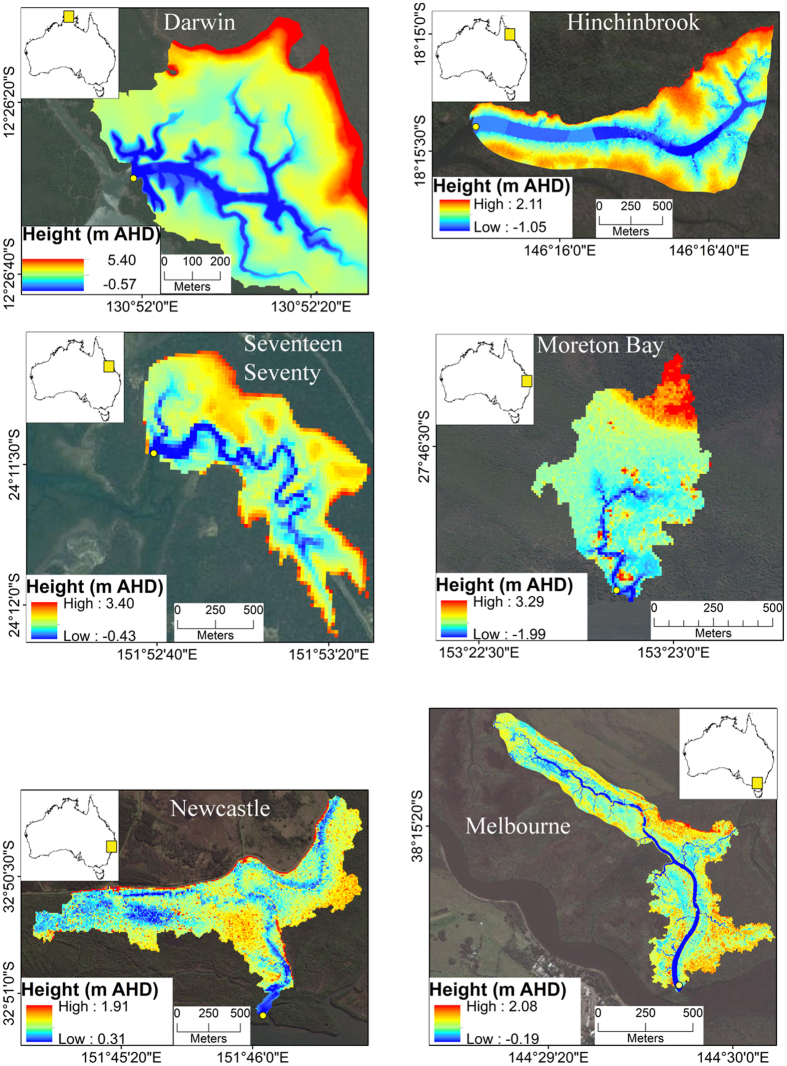

To understand the role of mangroves within global N2O budgets, we investigated dissolved N2O dynamics in six pristine mangrove tidal creeks covering a latitudinal gradient in Australia (Fig. 1, Table 1). We initially hypothesised that mangrove waters are a source of N2O to the atmosphere, which may play a disproportionately large role in global N2O budgets per unit area. To test this hypothesis we used novel, automated, quasi-continuous measurement technology that allowed for high temporal resolution, high precision dissolved N2O observations to be made in situ. Sites were selected to ensure the N2O observations were only related to mangrove sinks and sources. The sites had mangrove dominated catchments and no obvious upstream riverine input or anthropogenic nitrogen sources (Table 1).

Figure 1. Location of six mangrove creeks on the North and East coast of Australia and the associated digital elevation models (DEM).

Map and DEMs created with ESRI ArcGIS version 10.3 (https://www.arcgis.com). Image modified from Tait et al. (ref. 35).

Table 1. Study site characteristics during the 4 to 7 day time series deployments.

| Darwin | HinchinbrookIsland | SeventeenSeventy | MoretonBay | Newcastle | Melbourne | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude (°S) | 12.4° | 18.3° | 24.2° | 27.8° | 32.9° | 38.3° |

| No. of Mangrovespecies | 36 | 29 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| Tide Height | ||||||

| Max (m) | 7.1 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Min (m) | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Range (m) | 5.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

| Average (m) | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Air Temperature | ||||||

| Max (°C) | 27.9 | 23.2 | 20.0 | 28.6 | 26.4 | 21.2 |

| Min (°C) | 25.2 | 16.4 | 7.2 | 19.6 | 19.8 | 15.2 |

| Average (°C) | 26.5 ± 0.5 | 21.4 ± 0.7 | 16.8 ± 2.1 | 22.9 ± 1.7 | 23.6 ± 0.9 | 18.1 ± 1.4 |

| Ave yr temp (°C) | 32.0 ± 0.4 | 28.9 ± 0.5 | 25.7 ± 0.5 | 25.2 ± 1.0 | 21.6 ± 0.6 | 20.3 ± 0.6 |

| Ave rain (mm yr−1) | 1729 ± 377 | 2216 ± 677 | 1180 ± 326 | 1336 ± 389 | 1120 ± 268 | 621 ± 139 |

| Salinity | ||||||

| Max | 35.5 | 35.8 | 39.4 | 39.5 | 34.8 | 36.2 |

| Min | 34.7 | 35.0 | 35.7 | 35.4 | 28.1 | 27.6 |

| Average | 35.1 ± 0.2 | 35.3 ± 0.1 | 37.7 ± 1.1 | 37.0 ± 4.2 | 31.8 ± 1.6 | 34.4 ± 1.1 |

| Submerged area | ||||||

| Max (ha) | 72.6 | 286.3 | 109.0 | 37.0 | 126.6 | 29.8 |

| Min (ha) | 15.9 | 224.5 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 7.9 | 0.9 |

| Range (ha) | 56.7 | 61.8 | 105.9 | 36.2 | 118.7 | 28.9 |

| Average (ha) | 57.9 ± 11.1 | 275.6 ± 10.9 | 37.2 ± 37.8 | 25.8 ± 13.9 | 111.3 ± 31.0 | 4.8 ± 5.2 |

| Oceanic nutrient concentrations (μM)1 | ||||||

| IMOS station | NRSDAR | NRSYON | ** | NRSNSI | NRSPHB | NRSMAI |

| NO3 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 1.69 | 3.52 | 2.39 |

| NH4 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.18 |

1Data are average from nearest IMOS stations over the preceding 5 years, **Data are averaged from stations NRSYON and NRSNSI.

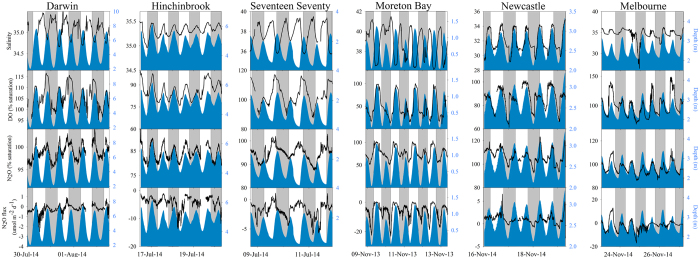

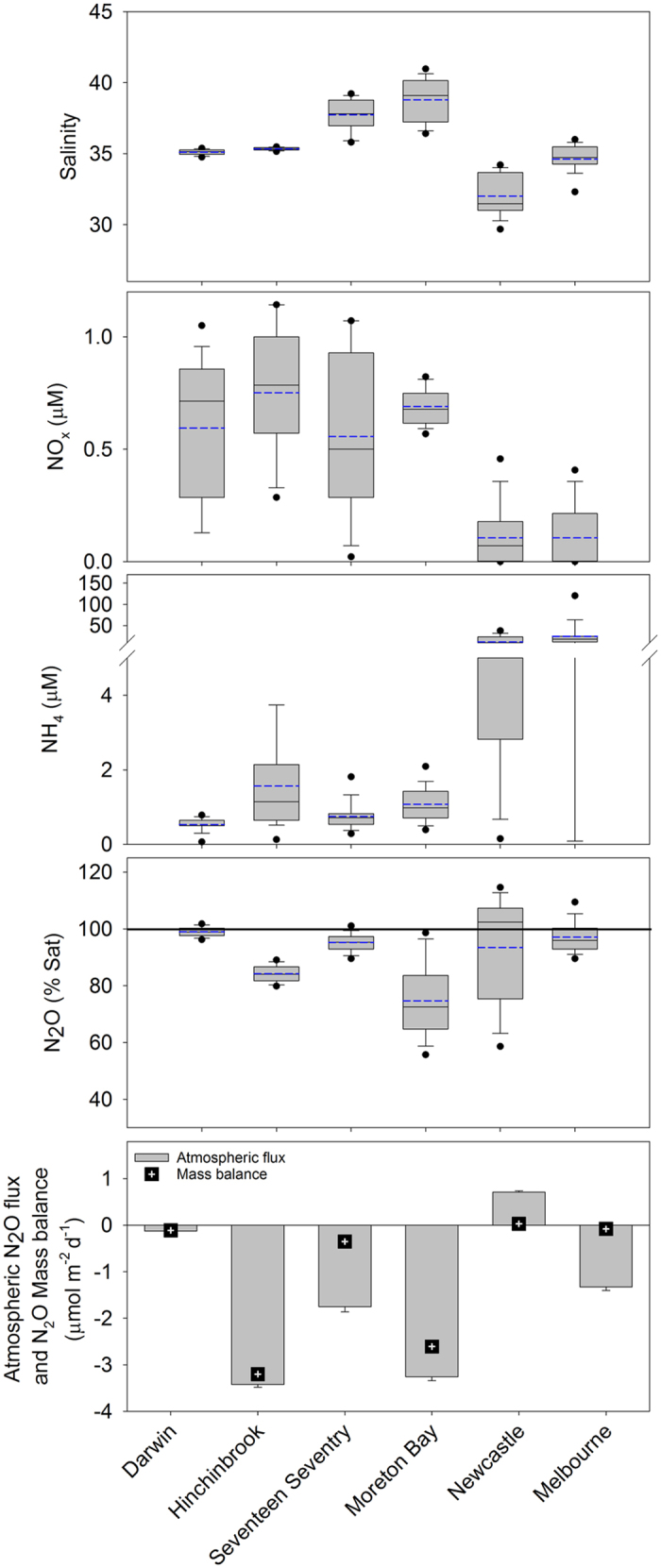

High temporal resolution observations over about 5 days in each creek revealed dissolved N2O concentrations ranging from 3.4–9.1 nM (50–123% saturation, Table 2, Figs 2 and 3). Nitrate + nitrite (NOx) concentrations in all the creeks were low (Fig. 3) and approached oceanic values, which average between 0.04 and 3.52 μM [Table 1, oceanic data was sourced from the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS)]. Ammonium (NH4) was higher in the two southern sites which also had lower salinity suggesting a freshwater source of NH4 to these systems. When data were averaged over the five days of the time series, five out of the six mangrove creeks were under-saturated in dissolved N2O, resulting in atmospheric N2O uptake by these waters (Fig. 3, Table 2, Supplementary Information). The only creek that was on average supersaturated in N2O (Newcastle) had the lowest salinity (Figs 2 and 3, Supplementary Information), suggesting freshwater inputs were the likely source of N2O supersaturation, or freshwater supplied the nitrogen fuelling N2O production.

Table 2. Field observations of inorganic nitrogen, N2O and estimates of air-water fluxes in six pristine Australian mangrove creeks.

| |

NOx Concentration (μM) |

NH4 concentration (μM) |

N2O concentration (nM) |

N2O saturation (%) |

Average atmospheric N2O fluxa (μmol m−2 d−1) | Weighted atmospheric N2O fluxb (μmol m−2 d−1) | N2O mass balancec (μmol m−2 d−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Latitude | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Daily integrated | Daily integrated |

| Darwin | −12.45 | 0.59 | <0.1–1.07 | 0.53 | <0.1–0.79 | 6.3 | 6.0–6.8 | 98.9 | 94.7–104.3 | −0.12 ± 0.01d> | −0.07d | −0.11 |

| Hinchinbrook | −18.25 | 0.75 | 0.29–1.14 | 1.56 | <0.1–5.93 | 6.1 | 5.6–6.9 | 83.3 | 75.4–90.5 | −3.43 ± 0.06d | −3.26d | −3.20 |

| Seventeen Seventy | −24.17 | 0.56 | <0.1–1.07 | 0.75 | 0.29–1.86 | 7.7 | 7.1–8.9 | 94.3 | 87.6–106.2 | −1.75 ± 0.11d | −0.48d | −0.35 |

| Moreton Bay | −27.78 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5.1 | 3.4–6.6 | 77.4 | 50.3–104.7 | −3.19 ± 0.08d | −1.52d | −2.61 |

| Newcastle | −32.85 | 0.11 | <0.1–0.50 | 12.69 | 0.5–40.14 | 7.5 | 6.4–8.9 | 106.4 | 92.1–123.4 | 0.71 ± 0.03d | 0.69d | 0.03 |

| Melbourne | −38.26 | 0.11 | <0.1–0.42 | 25.50 | <0.1–142.86 | 7.9 | 6.9–9.1 | 96.6 | 85.9–114.8 | −1.33 ± 0.07d | −0.12d | −0.08 |

| Average | 0.42 | <0.1–1.14 | 8.20 | <0.1–142.86 | 6.8 | 3.4–9.1 | 92.9 | 50.3–123.4 | −1.52 ± 0.17 | −0.79 ± 0.57 | −1.05 ± 0.59 | |

aPer m2 water area, ±95% confidence interval bweighted for changes in water area and flux rates over the study period and normalised to total catchment area, ccalculated as a function of discharge and dissolved N2O concentration integrated at 1 minute intervals, normalised to catchment area, dFlux rates determined using empirical transfer velocity equation of Ho et al.33.

Figure 2. Time series observations in the six mangrove tidal creeks.

Vertical grey bars represent night time period. Note the different Y axes scales to highlight temporal gradients. Solid blue shaded area represents tidal height. Salinty and depth data were originally reported in Tait et al. (ref. 35).

Figure 3. Box plots of salinity, nutrients and N2O data from time series observations (5th and 95th percentile, mean = solid black line, median is dashed blue line).

Nutrient data for Moreton Bay were from Gleeson et al. (ref. 22). Atmospheric N2O flux and N2O mass balance were mean ±95% confidence interval for each tidal cycle measured, corrected for tidal changes in creek area, and normalised to mangrove intertidal area.

The average N2O concentrations in each of the six mangrove creeks were lower than in the only previous study measuring dissolved N2O over a tidal cycle in mangrove waters which found mean concentrations of 9.0 ± 2.3 nmol L−1 (~170% saturation) (dry season) and 8.6 ± 1.3 nmol L−1 (~120% saturation) (wet season) over two 24 hour time series in the Andaman Islands11. Relatively high dissolved N2O concentrations are often found in rivers and inner estuaries, where catchment nitrogen inputs fuel N2O production through nitrification and denitrification13,14,15. With salinity ranging from 0 to 28 in the Andaman Island study, the higher N2O concentrations observed may have been driven by freshwater nitrogen loads, rather than mangrove related processes.

A complex combination of drivers may influence dissolved N2O production and consumption within mangrove ecosystems. Previous studies have found either nitrification6,11,16 or denitrification7,8,17 to be the dominant N2O production pathway in mangroves. N2O cycling is coupled to NOx and ammonium (NH4+) availability17, and a number of environmental factors such as denitrification and nitrifier bacteria abundance, redox potential, temperature, porewater or groundwater exchange, sulphur cycling, and local conditions such as topography, biomass, species composition and root structure7. For example, N2O concentration has been found to increase with; increasing denitrifier abundance18, increasing temperature13 , inputs of groundwater/porewater19 or through N2O reduction inhibition by H2S20, and reduced N2O production has been linked to low redox potentials in soils6.

Pristine mangrove waters generally have low inorganic nitrogen concentrations21. Mangroves may conserve nitrogen through nitrate reduction via dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) rather than denitrification22. This may enhance the N2O sink capacity of mangroves via two ways. First, N2O production through denitrification is inhibited due to competition for nitrate by DNRA. Second, DNRA bacteria and archaea possess the enzyme system required to catalyse the reduction of N2O to N223. Previously it was thought that denitrifiers were the only group capable of N2O reduction. In addition, some plants can produce and exude compounds that inhibit nitrification such as cyclic diterpenes24. Similar compounds have been found in the bark of mangrove roots25. These compounds may act as a chemical defence limiting nitrogen loss from highly productive mangrove ecosystems with limited nitrogen.

Overall, N2O atmospheric fluxes for individual systems ranged from −3.43 to 0.71 μmol m−2 d−1 (mean −1.52 ± 0.17 μmol m−2 d−1) when using well established flux models (Table 2). Using an independent mass balance approach, mangroves were estimated to have an atmospheric flux of −3.20 to 0.03 μmol m−2 d−1 (mean −1.05 ± 0.59 μmol m−2 d−1). Overall, these two independent approaches are consistent in that 5 out of the 6 systems were a sink for atmospheric N2O, giving confidence in our observations. The only system that released N2O to the atmosphere on average over the five day time series (Newcastle) also had the greatest input of freshwater (Figs 2 and 3).

Upscaling the N2O flux from mangrove waters in this study provides a first order estimate of fluxes from pristine mangrove systems. The mean atmospheric flux from the six sites was −1.52 (±0.17) μmol m−2 d−1 and the global mangrove area is estimated to be 0.36 × 106 km2 11 using the global forested area from Borges et al.26 (~0.2 × 106 km2), and the average wetland forest area from Selvam27 (0.16 × 106 km2), as done in the only other previous estimate of the global mangrove creek N2O flux11. The uncertainty associated with this estimate of creek area is unknown, but likely large. Assuming all global mangrove systems are in a pristine state is unrealistic, yet provides a first order estimate of the potential sink capacity of mangrove waters and allows for an update from the only previous estimate based on fluxes measured from one site during two 24 hour measurement campaigns11. Further, seasonal variability could not be determined during the current study. Adequate assessment of seasonality in N2O fluxes would be required to better constrain these estimates. In spite of these obvious caveats, if our estimates are representative of the N2O flux from pristine mangroves, the global N2O sink in pristine mangrove systems would be 2 × 108 mol yr−1. Previous estimates of N2O fluxes from mangrove systems reported a net source to the atmosphere, with global extrapolations of 2.7 × 109 mol yr−1 from mangrove soils and waters11, and ~3.2 × 108 to 13 × 1010 mol N2O yr−1 from soil emissions alone10. In contrast to our investigation, previous studies focused on systems with upstream freshwater inputs and therefore presumably some associated nitrogen inputs, which may fuel N2O production via nitrification and denitrification.

The sink nature of N2O within pristine mangroves is a rarity for aquatic systems, with most waterbodies being a source of N2O to the atmosphere. Estuaries and rivers are thought to contribute approximately 5% of the natural global N2O emissions from aquatic systems28. If our estimates are representative of mangroves globally, our results imply that pristine mangroves may offset about 3% of estuarine emissions (~7.14 × 109 mols yr−1)28, or 6% of N2O outgassing from rivers (~3.57 × 109 mols yr−1)28 and therefore play a relatively minor role within the global N2O budget from natural waterways. We suggest that the pristine mangrove N2O sink behaviour is related to nitrate limitation as well as microbial and plant inhibitory processes (Fig. 4). Combined with previous studies that indicate significant N2O releases from mangroves that are higher in nitrate11, our observations imply that human induced eutrophication, and in particular increased nitrogen loading may shift mangrove waters from a sink to a source of N2O to the atmosphere.

Figure 4. Conceptual model summarizing the potential processes controlling N2O dynamics in pristine mangrove creek waters.

Figure constructed using symbols courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Centre for Environmental Science (ian.umces.edu/symbols/).

Methods

This study was undertaken in six pristine mangrove tidal creeks on the Eastern and Northern Australian coast (Fig. 1; Table 1). Importantly, creeks were selected from low lying areas with small catchments in order to prevent significant upstream freshwater inputs that could mask processes occurring within intertidal mangroves. Therefore, freshwater input was assumed to occur only as a result of direct rainfall over the creek and the small intertidal areas.

To measure dissolved N2O, creek water was continually pumped from a depth of ~1 m into a showerhead air–water exchanger at a flow rate of approximately 3 L min−1. Continuous N2O concentrations (±2 ppb) were measured in the shower head exchanger at one second intervals for about five days at each site using a Picarro G2308 cavity ring-down spectrometer (CRDS) as described elsewhere29,30. The CRDS was calibrated using a 350 ppb standard (Air Liquide, Australia), prior to, and upon completion of the field measurements. Instrument drift was less than 2 ppb between calibrations (i.e. over several weeks). This 2 ppb drift equates to <0.10 nM at in situ temperature and salinity (assuming a total 4 ppb error in the concentration difference between the atmospheric and water column measurements). N2O dry molar fractions were converted to dissolved N2O concentrations as a function of pressure and solubility31 (1):

|

where β is the Bunsen solubility coefficient calculated from temperature and salinity32, x’ is the dry molar fraction of N2O and P is ambient pressure. Atmospheric pressure and temperature were measured with a weather station located on site (Davis Vanatge Pro II), and pressure and temperature within the equilibrator was measured with a temperature/pressure logger (Van Essen CTD logger).

At each site, estuarine current velocity and water depth were measured at fifteen minute intervals using an acoustic doppler current profiler (SonTek Argonaut). Salinity, water temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen were measured at 15 minute intervals using a calibrated multi-parameter water quality sonde (Hydrolab DS5). Dissolved nitrogen concentrations were measured on discrete samples collected hourly during a 24 hour time series (n = 25 per site), and analysed using flow injection analysis (Lachat Quickchem 8000). The samples were filtered with 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filters and kept frozen until analysis within 1 month. NOx detection limits were 0.07 μM (error ±3%) and NH4 detection limits were 0.35 μM (error ±5%).

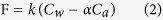

The flux of N2O in mangrove waters was estimated using two different approaches. First, we applied a gas exchange model. The transfer of N2O between the water and atmosphere was estimated as a function of the concentration in water and atmospheric concentration, solubility and gas transfer velocity at one minute intervals (2):

|

where k is the gas transfer velocity, Cw and Ca are the water and air phase concentrations respectively and α is the solubility coefficient.

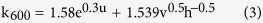

Gas transfer velocity was calculated using an empirical relationship developed specifically for mangroves33 (3):

|

where k600 is the gas transfer velocity normalised to a schmidt number of 600, u is the wind speed at a height of 10 m, v is current velocity (cm s−1) and h is water depth (m). Positive values indicate a flux of N2O from the water to the atmosphere, while negative values indicate gas exchange from the atmosphere to water. Atmospheric concentrations where measured with the same CRDS at least once per day for a period of 5 to 10 minutes. There was no significant difference between the atmospheric dry molar fractions measured at each site (ANOVA p > 0.05), therefore we used the pooled mean of 326 ppb for our atmospheric endmember. Wind speed data was sourced from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology for the nearest station near each site (all stations were within 20 km of the corresponding study site).

Second, we developed a mass balance approach that estimates the net water borne flux of N2O in and out of the mangrove catchment. Volumetric water discharge was calculated at one minute intervals using a high resolution LIDAR derived digital elevation model (DEM) with 1 m grid, ±0.1 m elevation accuracy, as described by Maher et al.34. The net exchange of N2O was then calculated as a function of concentration and discharge, with a mass balance constructed incorporating water borne exchange and the net air water flux within the mangroves. The air water flux was calculated as a function of time specific wetted area at one minute intervals, calculated using depth and the DEM.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Maher, D. T. et al. Pristine mangrove creek waters are a sink of nitrous oxide. Sci. Rep. 6, 25701; doi: 10.1038/srep25701 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Australian Research Council (ARC) through grants DE140101733, DE150100581 and LE140100083. We would like to thank Paul Macklin, Darren Williams and Frankie Makin for their valuable assistance in the field.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions D.T.M., I.R.S. and D.R.T. designed the experiment, D.T.M., D.R.T., J.Z.S. and C.H. undertook the field work and analysis D.T.M., J.Z.S. and I.R.S. wrote the manuscript, all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- Ciais P. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 465–570 (Cambridge University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Forster P. et al. in Climate Change 2007. The Physical Science Basis Ch. 2, 130–234 (Cambridge University Press, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- Seitzinger S. et al. Denitrification across landscapes and waterscapes: A synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 16, 2064–2090, doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2064:DALAWA]2.0.CO;2 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bange H. W., Rapsomanikis S. & Andreae M. O. Nitrous oxide in coastal waters. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 10, 197–207 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Alongi D. M. Carbon cycling and storage in mangrove forests. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 6, 195–219, doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135020 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauza J. F., Morell J. M. & Corredor J. E. Biogeochemistry of nitrous oxide production in the red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) forest sediments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 55, 697–704, doi: 10.1006/ecss.2001.0913 (2002). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. E. et al. Spatial and temporal variation of nitrous oxide and methane flux between subtropical mangrove sediments and the atmosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 622–631, doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.09.013 (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzwieser J., Buchholz J. & Rennenberg H. Emission of methane and nitrous oxide by Australian mangrove ecosystems. Plant Biol. 5, 423–431, doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42712 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. C., Tam N. F. Y. & Ye Y. Spatial and seasonal variations of atmospheric N2O and CO2 fluxes from a subtropical mangrove swamp and their relationships with soil characteristics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 48, 175–181, doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.01.029 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corredor J. E., Morell J. M. & Bauza J. Atmospheric nitrous oxide fluxes from mangrove sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 38, 473–478 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J. et al. Tidal dynamics and rainfall control N2O and CH4 emissions from a pristine mangrove creek. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L15405, doi: 10.1029/2006GL026829 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J. J. et al. Nitrous oxide emission from denitrification in stream and river networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 214–219, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011464108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J. & Upstill-Goddard R. C. N2O seasonal distributions and air-sea exchange in UK estuaries: Implications for the tropospheric N2O source from European coastal waters. J. Geophys. Res-Biogeo 116, doi: 10.1029/2009JG001156 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde H. P. J. & de Bie M. J. M. Nitrous oxide in the Schelde estuary: Production by nitrification and emission to the atmosphere. Mar. Chem. 69, 203–216 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Middelburg J. J. et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from estuarine intertidal sediments. Hydrobiologia 311, 43–55 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Hincapie M., Morell J. M. & Corredor J. E. Increase of nitrous oxide flux to the atmosphere upon nitrogen addition to red mangroves sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 44, 992–996 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley S. J. & Andrusiak S. M. Temperate mangrove and salt marsh sediments are a small methane and nitrous oxide source but important carbon store. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 97, 19–27, doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2011.11.002 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes S. O., Bharathi P. A. L., Bonin P. C. & Michotey V. D. Denitrification: An important pathway for nitrous oxide production in tropical mangrove sediments (Goa, India). J. Environ. Qual. 39, 1507–1516 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly C., Santos I. R., Cyronak T., McMahon A. & Maher D. T. Nitrous oxide and methane dynamics in a coral reef lagoon driven by porewater exchange: Insights from automated high frequency observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015GL063126, doi: 10.1002/2015GL063126 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen J., Tiedje J. M. & Firestone R. B. Inhibition by sulfide of nitric and nitrous oxide reduction by denitrifying Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39, 105–108 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson J., Santos I. R., Maher D. T. & Golsby-Smith L. Groundwater-surface water exchange in a mangrove tidal creek: Evidence from natural geochemical tracers and implications for nutrient budgets. Mar. Chem. 156, 27–37, doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2013.02.001 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes S. O., Bonin P. C., Michotey V. D., Garcia N. & LokoBharathi P. A. Nitrogen-limited mangrove ecosystems conserve N through dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium. Sci. Rep. 2, doi: 10.1038/srep00419 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford R. A. et al. Unexpected nondenitrifier nitrous oxide reductase gene diversity and abundance in soils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19709–19714, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211238109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao G. V. et al. Evidence for biological nitrification inhibition in Brachiaria pastures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17302–17307, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903694106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam C., Rao B. V., Ward R. S., Hurtshouse M. B. & Hibbs D. E. Diterpenes from the marine mangrove Bruguiera gymnorhiza. . Phytochemistry 51, 83–90 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Borges A. V. et al. Atmospheric CO2 flux from mangrove surrounding waters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, doi: 10.1029/2003GL017143 (2003). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selvam V. Environmental classification of mangrove wetlands of India. Curr. Sci. 84, 757–765 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B. et al. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from natural sources. Technical Report. Available at: http://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P100717T.txt (Accessed 11th November 2015) (2010).

- Maher D. T. et al. Novel use of cavity ring-down spectroscopy to investigate aquatic carbon cycling from microbial to ecosystem scales. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 12938–12945, doi: 10.1021/es4027776 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb J. R., Maher D. T. & Santos I. R. Automated, in situ measurements of dissolved CO2, CH4, and δ13C values using cavity enhanced laser absorption spectrometry: Comparing response times of air-water equilibrators. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods doi: 10.1002/lom3.10092 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo-Martínez D. L. et al. A new method for continuous measurements of oceanic and atmospheric N2O, CO and CO2: performance of off-axis integrated cavity output spectroscopy (OA-ICOS) coupled to non-dispersive infrared detection (NDIR). Ocean Sci. 9, 1071–1087, doi: 10.5194/os-9-1071-2013 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. F. & Price B. A. Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar. Chem. 8, 347–359, doi: 10.1016/0304-4203(80)90024-9 (1980). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. T., Ferrón S., Engel V. C., Larsen L. G. & Barr J. G. Air-water gas exchange and CO2 flux in a mangrove-dominated estuary. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 108–113, doi: 10.1002/2013GL058785 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maher D. T., Santos I. R., Golsby-Smith L., Gleeson J. & Eyre B. D. Groundwater-derived dissolved inorganic and organic carbon exports from a mangrove tidal creek: The missing mangrove carbon sink? Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 475–488, doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0475 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tait D. R., Maher D. T., Macklin P. A., Santos I. R. Mangrove porewater exchange across a latitudinal gradient. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, doi:10.10002/2016GL068289 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.