Abstract

Background

Aspiration pneumonia has been a growing interest in an aging population. Anaerobes are important pathogens, however, the etiology of aspiration pneumonia is not fully understood. In addition, the relationship between the patient clinical characteristics and the causative pathogens in pneumonia patients with aspiration risk factors are unclear. To evaluate the relationship between the patient clinical characteristics with risk factors for aspiration and bacterial flora in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in pneumonia patients, the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene was applied in addition to cultivation methods in BALF samples.

Methods

From April 2010 to February 2014, BALF samples were obtained from the affected lesions of pneumonia via bronchoscopy, and were evaluated by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in addition to cultivation methods in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP). Factors associated with aspiration risks in these patients were analyzed.

Results

A total of 177 (CAP 83, HCAP 94) patients were enrolled. According to the results of the bacterial floral analysis, detection rate of oral streptococci as the most detected bacterial phylotypes in BALF was significantly higher in patients with aspiration risks (31.0 %) than in patients without aspiration risks (14.7 %) (P = 0.009). In addition, the percentages of oral streptococci in each BALF sample were significantly higher in patients with aspiration risks (26.6 ± 32.0 %) than in patients without aspiration risks (13.8 ± 25.3 %) (P = 0.002). A multiple linear regression analysis showed that an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of ≥3, the presence of comorbidities, and a history of pneumonia within a previous year were significantly associated with a detection of oral streptococci in BALF.

Conclusions

The bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene revealed that oral streptococci were mostly detected as the most detected bacterial phylotypes in BALF samples in CAP and HCAP patients with aspiration risks, especially in those with a poor ECOG-PS or a history of pneumonia.

Keywords: Aspiration pneumonia, Aspiration risks, Oral streptococci, Anaerobes, Bacterial floral analysis; 16S ribosomal RNA gene

Background

Pneumonia is the third and ninth most common cause of death in Japan [1] and the United States [2], respectively. As the population ages, the mortality associated with pneumonia is increasing, especially among the elderly population of over 65 years of age [1].

The detection of the causative pathogens in pneumonia patients is generally based on sputum culture [3], but molecular methods using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence have yielded new bacteriological information for pneumonia [4–7]; specifically, that anaerobes and oral streptococci are important pathogens for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [5], healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) [7], ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [4, 6], and bacterial pleurisy [8]. The bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene we used have the advantages that can evaluate the ratio of each bacterial phylotype in each sample in addition to the ability to detect bacterial phylotypes that are difficult or impossible to be cultured [5, 7, 8].

Aspiration risks are important factors in elderly patients with pneumonia [9], as it can be highly influential to the causative pathogens. The guidelines for pneumonia recommend the use of effective antimicrobials to anaerobes in patients who are at risk for aspiration [10], however, there is insufficient etiological information of causative bacteria in these patients [11].

The objective of this study was to evaluate detected bacterial phylotypes by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in addition to cultivation methods in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) in patients with CAP and HCAP, and also to assess the relationship between the patient clinical characteristics with risk factors for aspiration and the most detected bacterial phylotypes by the bacterial floral analysis, using both simple and multiple regression analyses.

Methods

Study population

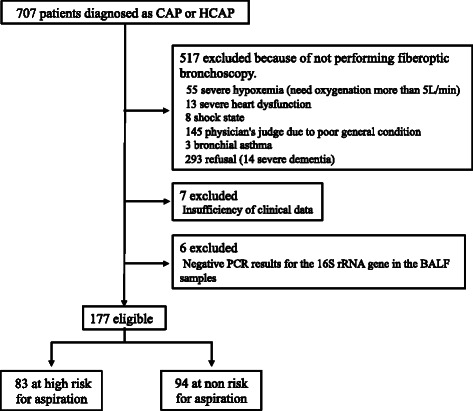

We recruited CAP (83) and HCAP (94) patients at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan and referred community hospitals between April 2010 and February 2014. Among these patients, 61 CAP [5] and 78 HCAP [7] patients were included in previous studies, and three of the CAP patients and four of the HCAP patients in the past studies were excluded because of insufficient samples or data (Fig. 1). The patients were classified into two groups: pneumonia patients with aspiration risk factors and those without. This study was approved by the Human and Animal Ethics Review Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (No.09–118). All patients provided written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

A flow chart of the participants in this study. Definitions of abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; HCAP, healthcare-associated pneumonia; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Definitions

CAP and HCAP were defined according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society guidelines [3]. The criteria for aspiration risk factors defined by Marik et al. [12] were used, that consist of having neurologic dysphagia, disruption of the gastroesophageal junction, or anatomical abnormalities of the upper aerodigestive tract. Patients with gastroesophageal disorders were categorized as “disruption of the gastroesophageal junction”. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance statuses (PS) were used, Grade 0; fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction, Grade one; restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g., light house work, office work, Grade two; ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities, up and about more than 50 % of waking hours, Grade three; capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50 % of waking hours, Grade four; Completely disabled, cannot carry on any self-care, totally confined to bed or chair, grade five; dead [13]. In this study, Streptococcus mutans group and the S. mitis group, the S. salivarius group, and the S. anginosus group were included as “oral streptococci” except for S. pneumoniae.

Data and sample collection

The clinical information of the patients, including the laboratory and radiological information on chest X-rays and computed tomography (CT) findings were collected. BALF specimens using 40 ml of sterile saline were obtained from pneumonia lesions, as described previously [5, 7].

Total cell count and cell lysis efficiency analysis

The total bacterial cell count and cell lysis efficiency were evaluated using epifluorescent microscopy, as previously described [5, 7, 8].

Microbiological evaluation using cultivation methods

The cultivation of BALF and sputum samples was performed as previously described [5, 7]. Positive results were recorded for all bacterial species. The presence of more than one positive BALF and/or sputum culture is described in the “Total” column of Table 2, while the positive culture results for BALF and sputum samples are presented in the corresponding columns of Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Predominant bacteria according to the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene and cultivation methods

| Total | Presence of risk factors for aspiration | Absence of risk factors for aspiration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone Library Method | Culture | Clone Library Method | Culture | Clone Library Method | Culture | ||||

| The predominant phylotypes in BALF | BALF | Sputum | The predominant phylotypes in BALF | BALF | Sputum | The predominant phylotypes in BALF | BALF | Sputum | |

| Gram-positive pathogens | |||||||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 23 (12.8) | 21 (11.7) | 12 (13.0) | 10 (11.9) | 7 (8.0) | 5 (12.0) | 13 (13.7) | 14 (15.2) | 7 (13.7) |

| Streptococcus spp. | 40 (22.3) | 9 (5.0) | 6 (6.5) | 26 (31.0) | 4 (4.5) | 2 (4.8) | 14 (14.7) | 5 (5.4) | 4 (7.8) |

| Streptococcus anginosus group | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other Streptococcus spp. | 35 (19.6) | 8 (4.4) | 6 (6.5) | 21 (25.0) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (4.8) | 14 (14.7) | 5 (5.4) | 4 (7.8) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 8 (4.5) | 21 (11.7) | 15 (16.1) | 4 (4.8) | 11 (12.5) | 8 (19.0) | 4 (4.2) | 10 (10.9) | 7 (13.7) |

| Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus | – | 7 (3.9) | 4 (4.3) | – | 5 (5.7) | 1 (2.4) | – | 2 (2.2) | 3 (5.9) |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | – | 14 (7.8) | 11 (11.8) | – | 6 (6.8) | 7 (16.7) | – | 8 (8.7) | 4 (7.8) |

| Staphylococcus spp. (except S. aureus) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Corynebacterium spp. | 6 (3.4) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gemella spp. | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lactobacillus spp. | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Rothia spp. | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gram-negative pathogens | |||||||||

| Haemophilus spp. | 28 (15.6) | 23 (12.8) | 10 (10.8) | 14 (16.7) | 8 (9.1) | 5 (12.0) | 14 (14.7) | 15 (16.3) | 5 (9.8) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 (5.6) | 18 (10.0) | 9 (9.7) | 2 (2.4) | 8 (9.1) | 3 (7.1) | 8 (8.4) | 10 (10.9) | 6 (11.8) |

| Pseudomonas spp. (except P. aeruginosa) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.0) |

| Moraxella spp. | 8 (4.5) | 7 (3.9) | 4 (4.3) | 5 (6.0) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (5.9) |

| Neisseria spp. | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Klebsiella spp | 4 (2.2) | 12 (6.7) | 6 (6.5) | 3 (3.6) | 10 (11.4) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Escherichia coli | 2 (1.1) | 5 (2.8) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.4) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Citrobacter spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serratia spp. | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Burkholderia spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Proteus spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pasteurella spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Anaerobic pathogens | 22 (12.3) | 8 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.0) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (17.9) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prevotella spp. | 11 (6.1) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fusobacterium spp. | 5 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Micromonas spp. | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Propionibacterium spp. | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Veillonella spp. | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Porphyromonas spp | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Peptostreptococcus spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Clostridium spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Atypical pathogens | |||||||||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 14 (7.8) | – | – | 2 (2.4) | – | – | 12 (12.6) | – | – |

| Legionella pneumonia | 1 (0.6) | – | – | 1 (1.2) | – | – | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Actinomyces spp. | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nocardia spp. | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Oral bacteria | – | 37 (20.9) | 24 (25.8) | – | 16 (18.2) | 7 (16.7) | – | 21 (22.8) | 17 (33.3) |

| No growth | – | 32 (18.1) | 4 (4.7) | – | 15 (18.1) | 1 (2.8) | – | 17 (18.1) | 3 (6.0) |

| Not analysed | – | – | 91 (51.4) | – | – | 47 (56.6) | – | – | 44 (46.8) |

| Total isolates | 179a | 180 | 93 | 84b | 88 | 42 | 95c | 92 | 51 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise stated. Percentages refer to the total number of isolates except “No growth” and “Not analysed”. “No growth” and “Not analysed” refer to the total number of cases. Definition of abbreviations: BALF: bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. a179 isolates of 177 cases (2 cases had two first predominant bacterial species.).b84 isolates of 83 cases.c95 isolates of 94 cases

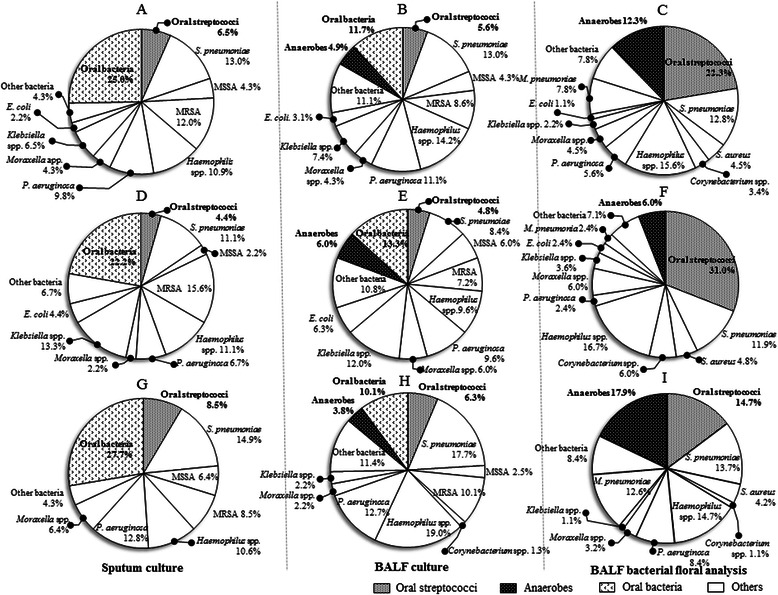

Fig. 2.

The percentages of the detected bacteria by sputum cultivation, and cultivation and the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The percentages of the bacterial species detected by the cultivation using sputum samples (a, d and g) or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (b, e and h), and the most detected bacterial phylotypes detected by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in BALF (c, f and i). The numbers in the Figures describe the percentages of detected bacteria in patients of all (a, b and c), with aspiration risks (d, e and f) and without aspiration risks (g, h and i), respectively. The denominators in a, b, d, e, g and h are the numbers of patients in whom some bacterial species were cultured, and the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene detected at least one or more bacterial phylotypes in all of the BALF samples (c, f and i). Ninety-one patients could not produce any sputum for examination at hospital admission (a, d and g). All members of the Streptococcus mutans and S. mitis groups, the S. salivarius group, and the S. anginosus group were included as “oral streptococci” except for S. pneumoniae (c, f and i). Definitions of abbreviations: MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus

The bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene

The DNA of 16S rRNA genes in BALF samples was extracted and the partial 16S rRNA gene fragments (approximately 580 base pairs) were amplified by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method with universal primers (341F and 907R). The amplified products were cloned into Escherichia coli using a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the nucleotide sequences of 96 randomly chosen clones were determined, and comparison of the detected sequences with the type strains using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) algorithm were performed, as described previously [5, 7, 8]. Using this method, each bacterial phylotype was precisely estimated including differentiation of S. pneumoniae and other streptococci in the BALF.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software package (version 19) was used, and Fisher’s exact test for tables (2 × 2), and the Mann–Whitney U test were applied. P < 0.05 was considered significant. When the most detected bacterial phylotypes were considered as dependent variables and clinical variables were considered as independent variables, a simple regression analysis was used. In addition, a multiple linear regression analysis was also performed. The variables were included in the original simple regression analysis model if their univariable P values were less than 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of 177 patients (CAP 83, HCAP 94) are shown in Table 1, and 46.9 % (83/177) patients had aspiration risks. Compared to the patients without aspiration risks, the patients with aspiration risks were significantly older, including more males and HCAP patients, higher rates of patients who resided in a nursing home or an extended care facility, lower average body mass indices (BMI), higher percentages of patients with median ECOG-PS of 3–4 of premorbid conditions, patients using antipsychotic drugs and patients with history of pneumonia within the previous 1 year (Table 1). The patients with aspiration risks demonstrated significantly higher percentages of patients with orientation disturbance, lower hematocrit values and average serum albumin levels, and more patients with posterior dominant distribution of infiltration on chest CT and more patients with a Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) score of VI-V than the patients without aspiration risks (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with or without risk factors for aspiration

| Variables | Presence of risk | Absence of risk | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| factors for aspiration | factors for aspiration | ||

| (n=83) | (n=94) | ||

| Age, years, mean±SD | 76.6 (9.5) | 64.5 (19.4) | <0.001 |

| Gender, male; n (%) | 58 (69.9) | 48 (51.1) | 0.011 |

| HCAP; n (%) | 59 (71.1) | 35 (37.2) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization for >2 days in the preceding 90 days | 34 (41.0) | 27 (28.7) | 0.087 |

| Residence in a nursing home or extended care facility | 29 (34.9) | 5 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Home infusion therapy (including antibiotics) | 10 (12.0) | 8 (8.5) | 0.437 |

| Chronic dialysis during the preceding 30 days | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0.346 |

| Home wound care | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI, mean±SDa | 19.6 (4.8) | 20.7 (4.5) | 0.038 |

| ECOG PS, median (IQR) | 2 (0.5–3.5) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | <0.001 |

| 0–1; n (%) | 28 (33.7) | 73 (77.7) | <0.001 |

| 2; n (%) | 22 (26.5) | 12 (12.8) | |

| 3–4; n (%) | 33 (39.8) | 9 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Smoking; n, (%)b | |||

| Smoker | 7 (10.0) | 9 (10.7) | |

| Ex-smoker | 30 (42.9) | 30 (35.7) | |

| Non smoker | 33 (47.1) | 45 (53.6) | |

| B.Ic | 493.7 (606.1) | 449.4 (641.7) | 0.454 |

| Comorbidity; n, (%) | |||

| Chronic respiratory disease | 22 (26.5) | 38 (40.4) | 0.051 |

| COPD | 11 (13.3) | 23 (24.5) | 0.059 |

| Bronchiectasis | 6 (7.2) | 12 (12.8) | 0.224 |

| Lung cancer | 7 (8.4) | 3 (3.2) | 0.132 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 6 (7.2) | 9 (9.6) | 0.576 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 30 (36.1) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Neuromuscular diseases | 19 (22.9) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Dementia | 26 (31.3) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Pharyngeal disorder | 7 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Gastroesophageal disorder | 27 (32.5) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (13.3) | 22 (23.4) | 0.084 |

| Malignancy excluding lung cancer | 26 (31.3) | 18 (19.1) | 0.060 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8 (9.6) | 8 (8.5) | 0.794 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (2.4) | 5 (5.3) | 0.450 |

| Chronic liver disease | 6 (7.2) | 2 (2.1) | 0.103 |

| RA or Sjogren’s syndrome | 0 (0.0) | 9 (9.6) | 0.004 |

| Collagen disease | 5 (6.0) | 7 (7.4) | 0.707 |

| Psychiatric disease | 2 (2.4) | 4 (4.3) | 0.686 |

| Medications; n (%) | |||

| Sleeping medications | 17 (20.5) | 10 (10.6) | 0.07 |

| Glucocorticoids (PSL>5 mg/day) | 11 (13.3) | 7 (7.4) | 0.202 |

| Immunosuppressive agent | 3 (3.6) | 8 (9.5) | 0.178 |

| Antipsychotic drugs | 7 (8.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0.027 |

| Antidepressant | 3 (3.6) | 6 (6.4) | 0.504 |

| History of pneumonia within the previous 1 year; n (%) | 24 (28.9) | 15 (16.0) | 0.038 |

| Respiratory failure; n, (%) | 31 (37.3) | 30 (31.9) | 0.448 |

| Clinical parameters; n, (%) | |||

| Orientation disturbance (confusion) | 21 (25.3) | 8 (8.5) | 0.003 |

| Systolic BP<90 mmHg or diastolic BP<60 mmHg | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.255 |

| Body temperature<35 °C or >40 °C | 4 (4.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0.188 |

| Pulse rate>125 beats/min | 5 (6.0) | 10 (10.6) | 0.271 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| BUN>10.7 mmol/L | 28 (33.7) | 24 (25.5) | 0.232 |

| Glucose>13.9 mmol/L | 3 (3.6) | 7 (7.4) | 0.339 |

| Hematocrit<30 % | 16 (19.3) | 6 (6.4) | 0.010 |

| Albumin, g/dl mean ± SDd | 3.05 (0.61) | 3.29 (0.57) | 0.011 |

| Radiographic findings; n, (%)e | |||

| Bilateral lung involvement | 54 (65.1) | 50 (53.8) | 0.128 |

| Upper lobe dominant opacity | 14 (16.9) | 20 (21.5) | 0.437 |

| Lower lobe opacity | 54 (65.1) | 52 (55.9) | 0.216 |

| anterior dominant opacity | 8 (9.6) | 14 (15.1) | 0.278 |

| posterior dominant opacity | 67 (80.7) | 58 (62.4) | 0.007 |

| Gravity-dependent opacity | 67 (80.7) | 67 (72.0) | 0.178 |

| Thickening of bronchovascular bundles | 37 (44.6) | 50 (53.8) | 0.224 |

| Pleural effusion | 12 (14.5) | 19 (20.3) | 0.299 |

| PSI score; mean±SD | 112.0 (40.3) | 81.0 (46.3) | <0.001 |

| I-III | 25 (30.1) | 57 (60.6) | |

| VI-V | 53 (69.9) | 37 (39.4) | <0.001 |

| In hospital mortality | 6 (7.2) | 6 (6.4) | 0.823 |

Definition of abbreviations: SD standard devision, CAP community-acquired pneumonia, HCAP healthcare-associated pneumonia, BMI body mass index, ECOG PS eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, BI brinkman index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, RA rheumatoid Arthritis, PSI pneumonia severity index

aBMI, bsmoking, cB.I, dserum albumin and, eradiographic findings were evaluated in 142, 154, 153, 168, and 176 patients, respectively

Total bacterial cell numbers and cell lysis efficiency analysis

The numbers of bacteria in the BALF samples ranged from 1.2 × 104 to 3.7 × 109 (median, 3.7 × 109) cells/mL. The cell lysis efficiency was maintained at ≥90 % in all samples.

The comparison of conventional cultivation methods and the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene

The results of the conventional cultivation methods and the most detected phylotypes using the bacterial floral analysis of the 16S rRNA gene in the BALF samples are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. The bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene identified one or more bacterial phylotypes in all of the BALF samples, whereas cultivation methods identified some microbes in 81.9 % (145/177) in BALF and 95.3 % (82/86) in sputum samples. The most detected bacterial phylotypes determined in the BALF using the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2. Oral streptococci (22.3 %), Haemophilus spp. (15.6 %), S. pneumoniae (12.8 %), anaerobes (12.3 %), and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (7.8 %) were mostly detected by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene. In contrast, the cultivation methods detected Haemophilus spp. (12.8 %), S. pneumoniae (11.7 %), Staphylococcus aureus (11.7 %), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10.0 %), while oral streptococci and anaerobes were isolated in only 5.0 and 4.4 % of the samples, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

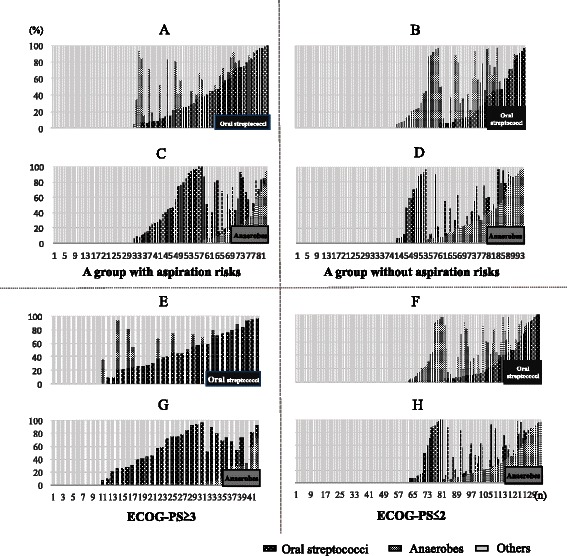

Comparison of the results of the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene between patients with or without aspiration risks

Using the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene, oral streptococci as the most detected phylotypes were significantly highly detected in patients with aspiration risks than patients without (31.0 and 14.7 %, respectively, P = 0.009); while anaerobes were significantly more detected in patients without aspiration risks (Fig. 2i) than patients with aspiration risks (Fig. 2f) (17.9 and 6.0 %, respectively, P = 0.015). Additionally, the percentages of oral streptococci were higher in patients with aspiration risks (Fig. 4a) than those without aspiration risks (Fig. 4b) (Fig. 3a, P = 0.002), and anaerobes were significantly more detected in patients without aspiration risks (Fig. 4d) than those with aspiration risks (Fig. 4c) (Fig. 3b, P = 0.044).

Fig. 4.

The percentages of oral streptococci (black), anaerobes (gray) and others (light gray) detected by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene in each bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample according to risks for aspiration and ECOG-PS. The percentages of oral streptococci (black), anaerobes (gray) and others (light gray) detected by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in each bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sample in patients with (a and c) or without (b and d) risks for aspiration, and those in patients with ECOG-PS of ≥3 (e and g) or ≤2 (f and h). a, b, e and f focus on the detection rate of oral streptococci (black) in each patient, and c, d, g and h focus on the detection rate of anaerobes (gray) in each patient. All members of the Streptococcus mutans and S. mitis groups, the S. salivarius group, and the S. anginosus group were included as “oral streptococci” except for S. pneumoniae. Abbreviation: ECOG-PS; european cooperative oncology group performance status

Fig. 3.

The occupancy of the phylotypes of oral streptococci and anaerobes by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene according to aspiration risks and ECOG-PS. a and c represents the occupancy of the phylotypes of oral streptococci, and (b and d) shows the occupancy of phylotypes of anaerobes, according to aspiration risks (a and b) and ECOG-PS (c and d). Using the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, the occupancy rates of oral streptococci were significantly higher in patients with aspiration risks than those in patients without aspiration risks (P = 0.02) (a), and were also significantly higher in patients with ECOG-PS of ≥3 compared to those in patients with ECOG-PS of ≤2 (P < 0.001) (c). In contrast, the occupancy rates of anaerobes were significantly higher in patients without aspiration risks than those in patients with aspiration risks (P = 0.044) (b), and similar trend was observed in patients with ECOG-PS of ≥3 compared to those in patients with ECOG-PS of ≤2 (P = 0.085) (d). All members of the Streptococcus mutans and S. mitis groups, the S. salivarius group, and the S. anginosus group, were included as “oral streptococci” except for S. pneumoniae. Abbreviation: ECOG-PS; European Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status

Results of simple and multiple linear regression analyses for detecting oral streptococci

Simple regression analysis was performed, using the most detected phylotypes such as oral streptococci (Fig. 2c) as the dependent variable and clinical variables (Table 3) as the independent variable. These variables were included in the original simple regression analysis model if their univariable P values were less than 0.05. The significantly correlated factors revealed by a simple regression analysis were; at an age of ≥80, an ECOG-PS of ≥3, residing in a nursing home or long-term care facility, the presence of aspiration risks, and a history of pneumonia within the previous one year (Table 3). The variables were included in the original simple regression analysis model if their univariable P values were less than 0.05. In addition, a multiple linear regression analysis revealed that an ECOG-PS ≥3 and a history of pneumonia were associated with the detection of oral streptococci in the BALF samples by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene (Table 4).

Table 3.

Result of simple regresssion analysis for detected oral streptococci

| b | SE (b) | β | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age >80 | 13.92 | 4.47 | 0.229 | 0.002 |

| BMI<20 | −4.07 | 2.89 | −0.106 | 0.161 |

| Hospitalization for >2 days in the preceding 90 day; n (%) | 4.15 | 4.63 | 0.068 | 0.371 |

| Residence in a nursing home or long-term care facility | 14.48 | 5.49 | 0.196 | 0.009 |

| Home infusion therapy (including antibiotics) | 9.88 | 7.26 | 0.102 | 0.170 |

| ECOG PS of premorbid condition>3 | 23.37 | 4.87 | 0.341 | <0.001 |

| COPD | −0.28 | 5.60 | −0.004 | 0.960 |

| Interstitial pneumonia | 0.18 | 7.92 | 0.002 | 0.982 |

| Lung cancer | −0.16 | 9.55 | −0.001 | 0.987 |

| Bronchiectasis | −6.63 | 7.28 | −0.069 | 0.364 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7.75 | 5.85 | 0.100 | 0.187 |

| Neuromuscular diseases | 8.62 | 7.09 | 0.092 | 0.226 |

| Dementia | 8.14 | 6.20 | 0.099 | 0.191 |

| Gastroesophageal disorder | 5.72 | 6.12 | 0.705 | 0.351 |

| Pharyngeal disorder | 19.48 | 11.22 | 0.130 | 0.084 |

| Presence of the risk factor for aspiration | 12.78 | 4.31 | 0.219 | 0.004 |

| Malignancy excluding lung cancer | −1.73 | 5.10 | −0.026 | 0.735 |

| Psychiatric disease | 1.68 | 12.18 | 0.010 | 0.891 |

| Sleeping medications | 10.24 | 6.08 | 0.126 | 0.094 |

| Antipsychotic drugs | −4.94 | 10.61 | −0.035 | 0.642 |

| Antidepressant | 10.40 | 10.01 | 0.078 | 0.300 |

| History of pneumonia within the previous 1 year | 16.12 | 4.92 | 0.241 | 0.001 |

| Albumin<4 g/dl | −3.25 | 6.56 | −0.037 | 0.621 |

| Bilateral lung involvement | 0.01 | 4.37 | 0.0002 | 0.998 |

| Lower lobe opacity | −4.67 | 4.40 | −0.08 | 0.291 |

| Posterior dominant opacity | 4.56 | 4.87 | 0.071 | 0.351 |

| Gravity-dependent opacity | −7.52 | 5.27 | −0.107 | 0.155 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI body mass index, ECOG PS eastern cooperative oncology group performance status, HCAP healthcare-associated pneumonia, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 4.

Result of multiple linear regresssion for detected oral streptococci

| b | SE (b) | β | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age>80 | 6.61 | 4.62 | 0.109 | 0.154 |

| Residence in a nursing home or long-term care facility | −3.28 | 6.4 | −0.044 | 0.609 |

| ECOG PS of premorbid condition>3 | 17.52 | 5.96 | 0.256 | <0.001 |

| Presence of the risk factor for aspiration | 5.69 | 4.54 | 0.097 | 0.211 |

| History of pneumonia within the previous 1 year | 10.36 | 4.88 | 0.155 | 0.035 |

b: raw (unstandardised) regression coefficient, SE standard error of b coefficient

Results of the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene in pneumonia patients with an ECOG-PS of ≥3 or ≤2

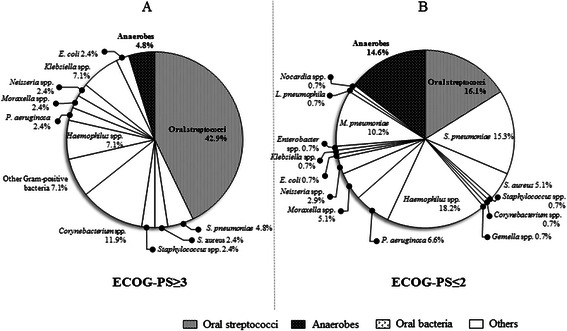

As the most detected bacterial phylotypes, oral streptococci were significantly more frequently detected in pneumonia patients with an ECOG-PS of ≥3 than those ≤2 (P < 0.001), while anaerobes were less frequently detected but not significantly different (Fig. 5). The percentages of oral streptococci were significantly highly detected in each BALF in patients with ECOG-PS ≥3 (Fig. 4e) than those with ECOG-PS ≤2 (Fig. 4f) (Fig. 3c, P < 0.001), and those of anaerobes were highly observed in each BALF in patients with ECOG-PS ≤2 (Fig. 4h) than ECOG-PS ≥3 (Fig. 4g), but not significantly different (Fig. 3d, P = 0.085).

Fig. 5.

The differences of the percentages of the most detected bacterial phylotypes determined by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene according to ECOG-PS. The percentages of the most detected bacterial phylotypes by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene in patients with ECOG-PS ≥3 (a) included significantly more oral streptococci than those in patients with ECOG-PS ≤2 (b) (P < 0.001). All members of the Streptococcus mutans and S. mitis groups, the S. salivarius group, and the S. anginosus group were included as “oral streptococci” except for S. pneumoniae. Abbreviation: ECOG-PS; european cooperative oncology group performance status

Discussion

This study firstly analyzed the relationship between the bacterial flora in the lung and the aspiration risks in patients with CAP and HCAP, and the bacterial floral analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene using the BALF specimens obtained from 83 CAP and 94 HCAP patients revealed that oral streptococci were the most detected bacterial phylotypes (Fig. 2c). This is in line with our previous results that demonstrated the significantly higher detection of oral streptococci in CAP patients [5]. However, the clinical implication of the detection of oral streptococci in relation to risk factors for aspiration and clinical background factors have not been fully understood. In this study, oral streptococci were significantly more frequently detected with high occupancy in pneumonia patients with aspiration risks than in those without aspiration risks (Figs. 3a and 4a, b). Moreover, the high occupancy of oral streptococci in each sample was strongly correlated with ECOG-PS ≥ 3 (Figs. 3c and 4e, f). In addition, this study firstly showed that having a poor ECOG-PS (≥3) and a history of pneumonia within the previous one year showed a greater correlation with the detection of oral streptococci in the BALF than having aspiration risks (Table 4).

Oral streptococci have been reported to be common causative pathogens of pulmonary abscesses and empyema thoracis [14–17], and the rate of oral streptococci as causative pathogens in patients with CAP or HCAP was reported to be 0.3–14.1 % [18–27]. Higher incidence of oral streptococci (22.3 %) as the most detected phylotypes in the BALF using the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene was observed compared to the previous reports including our report of CAP patients (9.4 %) [5]. In addition, higher rates of oral streptococci were detected in both patients with aspiration risks (31.0 %) and without (14.7 %) (Fig. 3c, f) than the previously reported detection rates of oral streptococci in patients with aspiration (1.9–41.2 %) [14, 28–32] and non-aspiration pneumonia (3.6–9.1 %) [30, 32]. The different bacteriological detection methods may have influenced these different detection rates of oral streptococci [30, 32]. Conventional cultivation methods cannot evaluate the bacterial ratio in each sample, whereas the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene we used can estimate the ratio of bacterial phylotypes in each sample. According to the result, the percentages of oral streptococci in each BALF sample in patients with aspiration risks were significantly higher than those in patients without aspiration risks (Fig. 3a).

The factors correlated with the detection of oral streptococci in pneumonia patients by simple regression analysis were similar to the previous reports (Table 3) [15]. Detection of oral streptococci by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene were strongly correlated to a risk of aspiration in this study, and the strongest correlation factor for the detection of oral streptococci in pneumonia patients in this study was a poor ECOG-PS (≥3) (Table 4).

Oral streptococci (22.3 %) were the most frequently detected bacterial phylotypes (Fig. 2c), whereas the conventional cultivation method demonstrated that oral streptococci and anaerobes were isolated in only 5.0 and 4.4 % of the same samples, respectively (Fig. 2b). In real-word clinical settings, oral streptococci and anaerobes might be considered as oral contaminants and could be underestimated by cultivation methods. We have previously shown that the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene using BALF samples did not make remarkable oral floral contaminations in noninfectious patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias [5], and also all patients showed a total bacterial cell count of >104 cells/mL in BALF that was a useful diagnostic criterion for pulmonary bacterial infection [5], therefore, we think that the oral streptococci and anaerobes that were highly detected in the lower respiratory tract in this study were reliable, and speculate that oral streptococci have important roles in patients with pneumonia with aspiration risk factors.

The detection rates of anaerobes in patients with aspiration pneumonia were 87.5–100 % in the studies using percutaneous transtracheal aspirates [28–30]. However, Marik et al. suggested that these high rates might be excessive [12], primarily due to their later sampling time of percutaneous transtracheal aspirates in the clinical course of the illness. This might include other complications such as abscesses, necrotizing pneumonia, or empyema in the previous studies [28–30], and transtracheal sampling may also have possibly provoked the aspiration of the oropharyngeal flora during the procedure. Anaerobes were detected in only 11.6 % of samples in other report evaluating using protected BALF specimens in patients with severe aspiration pneumonia in a population of institutionalized elderly [14], and no anaerobes were detected using a protected specimen brush [31, 33]. The bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene demonstrated that anaerobes were detected in 12.3 % of this study population (Fig. 2c), and significantly highly detected in patients without aspiration risks (17.9 %, Fig. 2i) than with aspiration risks (6.0 %, Fig. 2f). The percentages of anaerobes in each BALF sample in patients without aspiration risks were also significantly higher than those with aspiration risks (Figs. 3b and 4c, d), and according to these results, anaerobes might not be the primary cause of pneumonia in patients with aspiration risks. El-Solh et al. [14] also reported the relationship between the detection of anaerobes in the lower respiratory tract and oral hygiene, further studies are necessary to clarify these clinical relationships.

This study is associated with several limitations. First, this study was retrospective and subject to a recall bias. Second, the universal primers that were used in the bacterial floral analysis could not amplify all of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes, and the sensitivity of the primers was approximately 92 % of the total bacterial species registered in the Ribosomal Database Project II database, whereas no reported human causative pathogens were included in the remaining 8 %. Third, only approximately 100 clones were analyzed per library, suggesting that bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences present at very small fractions (<1 % of each sample) in the sample may occasionally be undetectable. In addition, the sequencing depth was insufficient for the detection of mycobacterial species. Fourth, this study only included patients in whom bronchoscopic examination was performed.

Conclusions

Using the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene, oral streptococci were the most detected bacterial phylotypes in CAP and HCAP patients with aspiration risks, and both simple and multiple regression analyses demonstrated that the detection of oral streptococci in the BALF by the bacterial floral analysis of 16S rRNA gene was strongly related to poor ECOG-PS (≥3). The evaluation of the patients’ physical activities to estimate the aspiration risks and bacterial etiologies might be important, and a poor ECOG-PS might be a clue to the higher detection rate of oral streptococci in the lower respiratory tract in patients with CAP and HCAP.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Human and Animal Ethics Review Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (No.09–118), and all patients provided their written informed consent.

Availability of data and materials

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yukikazu Awaya, Chiharu Yoshii, Hideto Obata, Yukiko Kawanami, Yugo Yoshida, Takashi Kido, Takeshi Orihashi, Chinatsu Nishida, Naoyuki Inoue, Takaaki Ogoshi, Susumu Tokuyama, Minako Hanaka, Yu Suzuki, Keishi Oda, Kanako Hara and Tetsuya Hanaka for collecting clinical data, and Ms. Yoshiko Yamazaki, Michiyo Taguchi, Kumiko Matsuyama for their technical supports. This study was partially supported by a High Altitude Research Grant from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, and a Research Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C), 23591173, 2011.

Abbreviations

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BLAST

basic local alignment search tool

- BMI

body mass index

- CAP

community-acquired pneumonia

- CT

computed tomography

- ECOG-PS

eastern cooperative oncology group-performance status

- HCAP

healthcare-associated pneumonia

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PSI

pneumonia severity index

- VAP

ventilator-associated pneumonia

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB JY carried out the immunoassays. MT participated in the sequence alignment. ES participated in the design of the study. FG conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. KA, KY and KY conceived the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted of data and drafted the manuscript. KA, KY, TK, KN, SN, KF and HI collected clinical data, carried out the molecular studies. KY, HT and HM reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Summary of Vital Statistics; Trends in leading causes of death. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, Tokyo. 2013. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/populate/index.html. Accessed 5 May 2015.

- 2.Health, United States, 2013, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus13.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2015.

- 3.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Paster BJ, Coleman S, Barbuto S, Brennan MT, Noll J, et al. Molecular analysis of oral and respiratory bacterial species associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1588–93. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01963-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamasaki K, Kawanami T, Yatera K, Fukuda K, Noguchi S, Nagata S, et al. Significance of anaerobes and oral bacteria in community-acquired pneumonia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bousbia S, Papazian L, Saux P, Forel JM, Auffray JP, Martin C, et al. Repertoire of intensive care unit pneumonia microbiota. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noguchi S, Mukae H, Kawnami T, Yamasaki K, Fukuda K, Akata K, et al. Bacteriological Assessment of Healthcare-associated Pneumonia using a Clone Library Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawanami T, Fukuda K, Yatera K, Kido M, Mukae H, Taniguchi H. A higher significance of anaerobes: the clone library analysis of bacterial pleurisy. Chest. 2011;139:600–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teramoto S, Fukuchi Y, Sasaki H, Sato K, Sekizawa K, Matsuse T. High incidence of aspiration pneumonia in community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a multicenter, prospective study in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:577–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventive strategies. A consensus statement, American Thoracic Society, November 1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1711-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Marik PE, Kaplan D. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest. 2003;124:328–36. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:665–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103013440908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity And Response Criteria Of The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, Aquilina AT, Okada M, Grover V, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneumonia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1650–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1543OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinzato T, Saito A. The Streptococcus milleri group as a cause of pulmonary infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(Suppl 3):S238–43. doi: 10.1093/clind/21.Supplement_3.S238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed RA, Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Thoracic empyema in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2006;119:877–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takayanagi N, Kagiyama N, Ishiguro T, Tokunaga D, Sugita Y. Etiology and outcome of community-acquired lung abscess. Respiration. 2010;80:98–105. doi: 10.1159/000312404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyashita N, Fukano H, Mouri K, Fukuda M, Yoshida K, Kobashi Y, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in Japan: a prospective ambulatory and hospitalized patient study. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:395–400. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishida T, Hashimoto T, Arita M, Tojo Y, Tachibana H, Jinnai M. A 3-year prospective study of a urinary antigen-detection test for Streptococcus pneumoniae in community-acquired pneumonia: utility and clinical impact on the reported etiology. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:359–63. doi: 10.1007/s10156-004-0351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito A, Kohno S, Matsushima T, Watanabe A, Oizumi K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Prospective multicenter study of the causative organisms of community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2006;12:63–9. doi: 10.1007/s10156-005-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang GD, Fine M, Orloff J, Arisumi D, Yu VL, Kapoor W, et al. New and emerging etiologies for community-acquired pneumonia with implications for therapy. A prospective multicenter study of 359 cases. Med (Baltimore) 1990;69:307–16. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortqvist A, Kalin M, Lejdeborn L, Lundberg B. Diagnostic fiberoptic bronchoscopy and protected brush culture in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 1990;97:576–82. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.3.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrie TJ. Bacteremic community-acquired pneumonia due to viridans group streptococci. Clin Invest Med. 1993;16:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128:3854–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, Ando M, Ichikawa M, Shiraki A, et al. Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:985–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0079OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong BH, Koh WJ, Yoo H, Um SW, Suh GY, Chung MP, et al. Performances of prognostic scoring systems in patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:625–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugisaki M, Enomoto T, Shibuya Y, Matsumoto A, Saitoh H, Shingu A, et al. Clinical characteristics of healthcare-associated pneumonia in a public hospital in a metropolitan area of Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:352–60. doi: 10.1007/s10156-011-0344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartlett JG, Gorbach SL, Finegold SM. The bacteriology of aspiration pneumonia. Am J Med. 1974;56:202–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorber B, Swenson RM. Bacteriology of aspiration pneumonia. A prospective study of community- and hospital-acquired cases. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:329–31. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-3-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cesar L, Gonzalez C, Calia FM. Bacteriologic flora of aspiration-induced pulmonary infections. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:711–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.135.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mier L, Dreyfuss D, Darchy B, Lanore JJ, Djedaïni K, Weber P, et al. Is penicillin G an adequate initial treatment for aspiration pneumonia? A prospective evaluation using a protected specimen brush and quantitative cultures. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19:279–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01690548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leroy O, Vandenbussche C, Coffinier C, Bosquet C, Georges H, Guery B, et al. Community-acquired aspiration pneumonia in intensive care units. Epidemiological and prognosis data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1922–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9702069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marik PE, Careau P. The role of anaerobes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia: a prospective study. Chest. 1999;115:178–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described in the article.