MK-5046, a bombesin-like receptor 3 (BRS-3) agonist, increases heart rate and blood pressure via increased central sympathetic tone. Brs3 null mice have a reduced resting heart rate that increases disproportionately with physical activity. BRS-3 contributes to the central regulation of heart rate and blood pressure.

Keywords: bombesin-like receptor 3, blood pressure, heart rate, sympathetic nervous system, energy metabolism

Abstract

Bombesin-like receptor 3 (BRS-3) is an orphan G protein-coupled receptor that regulates energy expenditure, food intake, and body weight. We examined the effects of BRS-3 deletion and activation on blood pressure and heart rate. In free-living, telemetered Brs3 null mice the resting heart rate was 10% lower than wild-type controls, while the resting mean arterial pressure was unchanged. During physical activity, the heart rate and blood pressure increased more in Brs3 null mice, reaching a similar heart rate and higher mean arterial pressure than control mice. When sympathetic input was blocked with propranolol, the heart rate of Brs3 null mice was unchanged, while the heart rate in control mice was reduced to the level of the null mice. The intrinsic heart rate, measured after both sympathetic and parasympathetic blockade, was similar in Brs3 null and control mice. Intravenous infusion of the BRS-3 agonist MK-5046 increased mean arterial pressure and heart rate in wild-type but not in Brs3 null mice, and this increase was blocked by pretreatment with clonidine, a sympatholytic, centrally acting α2-adrenergic agonist. In anesthetized mice, hypothalamic infusion of MK-5046 also increased both mean arterial pressure and heart rate. Taken together, these data demonstrate that BRS-3 contributes to resting cardiac sympathetic tone, but is not required for activity-induced increases in heart rate and blood pressure. The data suggest that BRS-3 activation increases heart rate and blood pressure via a central sympathetic mechanism.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

MK-5046, a bombesin-like receptor 3 (BRS-3) agonist, increases heart rate and blood pressure via increased central sympathetic tone. Brs3 null mice have a reduced resting heart rate that increases disproportionately with physical activity. BRS-3 contributes to the central regulation of heart rate and blood pressure.

obesity is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension (6). However, the mechanisms linking obesity and hypertension are not fully understood (7, 44). A number of neuroendocrine systems controlling energy homeostasis also regulate blood pressure and heart rate, including leptin, the melanocortin system, and ghrelin (12, 36, 45, 48–50). The genetic and pharmacological manipulations of these systems that reduce adiposity generally also increase blood pressure, which is undesirable in a treatment for obesity.

Bombesin-like receptor 3 (BRS-3) is a G protein-coupled receptor for which the endogenous ligand is unidentified (4, 21, 29, 33). Despite the name, BRS-3 has a low affinity for bombesin and the related molecules, neuromedin B and gastrin-releasing peptide (34). BRS-3, like the leptin and melanocortin system, regulates energy metabolism and food intake. BRS-3 is located in several brain regions that regulate energy metabolism, including several hypothalamic nuclei and the caudal brain stem (14, 20, 31, 40, 53, 54). Brs3 knockout (Brs3−/y) mice exhibit hyperphagia, reduced metabolic rate, and obesity (27, 41). Treatment with a BRS-3 antagonist increased food intake and body weight in rats (14). Concordantly, BRS-3 agonists reduced food intake, increased metabolic rate, and reduced body weight in mice, rats, and dogs (14, 15).

Existing evidence for a role of BRS-3 in regulation of blood pressure is contradictory. One BRS-3 agonist, MK-5046, transiently increased blood pressure in rats, dogs, and humans (but has not been studied in mice) (15, 46). A different BRS-3 agonist also increased blood pressure, while a third agonist reduced it, making it unclear if the blood pressure effects are mediated via BRS-3 (15). Confusingly, Brs3−/y mice were reported to have increased tail-cuff blood pressure at 40 wk, but not at 16 wk of age (41). Thus the reported phenotype of the Brs3−/y mice is the opposite of that predicted from most pharmacological experiments.

Given this ambiguity, we dissected the interactions between BRS-3 and blood pressure and heart rate using both genetic (Brs3−/y mice) and pharmacological tools. From studying resting and active mice, we identified an interaction between BRS-3 and physical activity. We also explored the intrinsic heart rate in Brs3−/y mice and the contribution of sympathetic input to the increase in blood pressure and heart rate by the BRS-3 agonist, MK-5046.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds and Mice

MK-5046, (2S)-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-[4-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)phenyl]-3-(4-{[1-(trifluoromethyl)cyclopropyl]methyl}-1H-imidazol-2-yl)propan-2-ol, is a potent (mouse BRS-3 Ki = 1.6 nM), brain-penetrant and highly selective BRS-3 agonist (47) that was synthesized and generously provided by Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ. The parenteral MK-5046 doses (1 and 3 mg/kg ip) are selective, without activity in Brs3−/y mice (15, 28). Clonidine hydrochloride [40 μg/kg ip (3)], propranolol [5 mg/kg ip (23)], and atropine [1 mg/kg ip (42)] were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), with dosing based on the indicated references.

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred in house, and Brs3−/y mice were provided by Dr. James Battey (27) and back-crossed at least eight generations onto a C57BL/6J background. Male mice were studied at 12–24 wk of age using littermate controls. Mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and with food and water available ad libitum. All animal studies were approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/National Institutes of Health Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hemodynamic Measurements in Conscious Mice

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured in conscious, unrestrained mice via radiotelemetry (DSI PhysioTel PA-C10 transmitter and Ponemah v4.80 software, Data Sciences International) with sampling at 500 Hz (24). Mice were allowed 7 days to recover from surgery and acclimatized to handling with vehicle intraperitoneal injections each day for the 5 days prior to dosing with drug.

Heart rate variability in the time domain was calculated as the pNN6, the percent of consecutive RR intervals differing by >6 ms (51), without excluding the RR intervals outside the 95.5% confidence intervals.

The cardiovagal baroreceptor reflex was investigated using spontaneous changes in blood pressure and heart rate in 1 h of light-phase data (0900–1000) by the sequence method (30) as described (17). Briefly, baroreceptor sensitivity (ms/mmHg) was calculated as the slope of the linear regression between SBP and the corresponding RR intervals using sequences defined as an episode of ≥3 heartbeats with changes of >0.01 mmHg SBP and >0.01 ms per beat in the same direction. The median of the slopes with an R squared value >0.85 was calculated for blood pressure upslopes (BRSup) and downslopes (BRSdown) and an R-R response delay of 0, 1, or 2 heartbeats. Data containing movements and other artifacts in the SBP or RR interval series were excluded. All baroreceptor sensitivity analysis was performed using customized software (PHYSIOWAVE BRSSpectra) programmed (by A.D. and R.J.B) using MatLab.

Hemodynamic Measurements during Anesthesia

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (80 mg/kg ip) and catheterized via the jugular vein using PE-10 tubing. A high-fidelity 1.4-F Millar microtip catheter (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO) was inserted via the left carotid artery as described (18). Anesthetized mice were kept on a small-animal operating table set at 35°C. MK5046 was dissolved in 5% dimethylacetamide in saline and infused in 1 μl/g body wt. Blood pressure and heart rate were digitized using PowerLab 4/25 and Lab Chart Pro Data Acquisition Software (ADInstruments).

Intrahypothalamic Infusions

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (80/10 mg/kg ip). Sterile guide cannulas (5.25 mm, 26 gauge, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were stereotaxically implanted bilaterally into the anterior hypothalamus [1.34 mm posterior, ±0.75 mm lateral to bregma, 4.75 mm below the surface of the skull (9)] and fixed with dental cement (Parkell, Edgewood, NY). MK-5046 or vehicle (saline) was infused (1 μg/1 μl per side over 60 s) through a 33-gauge cannula protruding 0.5 mm past the tip of the guide cannula using PE-10 tubing fitted to a 5-μl syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) and dual-syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA). Cannula positions in the anterior hypothalamus were verified by postmortem histology. The mouse hypothalamus is ∼10 mm3 (1); the large infusion volume was used so that drug would reach Brs3 in adjacent brain nuclei (14, 20, 31, 40, 53, 54).

Statistics

Results are shown as means ± SE. Two-way ANOVA with or without repeated measures followed by Holm-Šídák's post test was used for comparing genotypes vs. the treatment groups. Student's t-test was used when two groups were compared. Statistical analyses used two-tailed tests using P < 0.05 as statistically significant. Least-squares model analysis was performed using JMP 10.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Studies in Brs-3 Deficient Mice

Blood pressure and heart rate in conscious Brs3−/y mice.

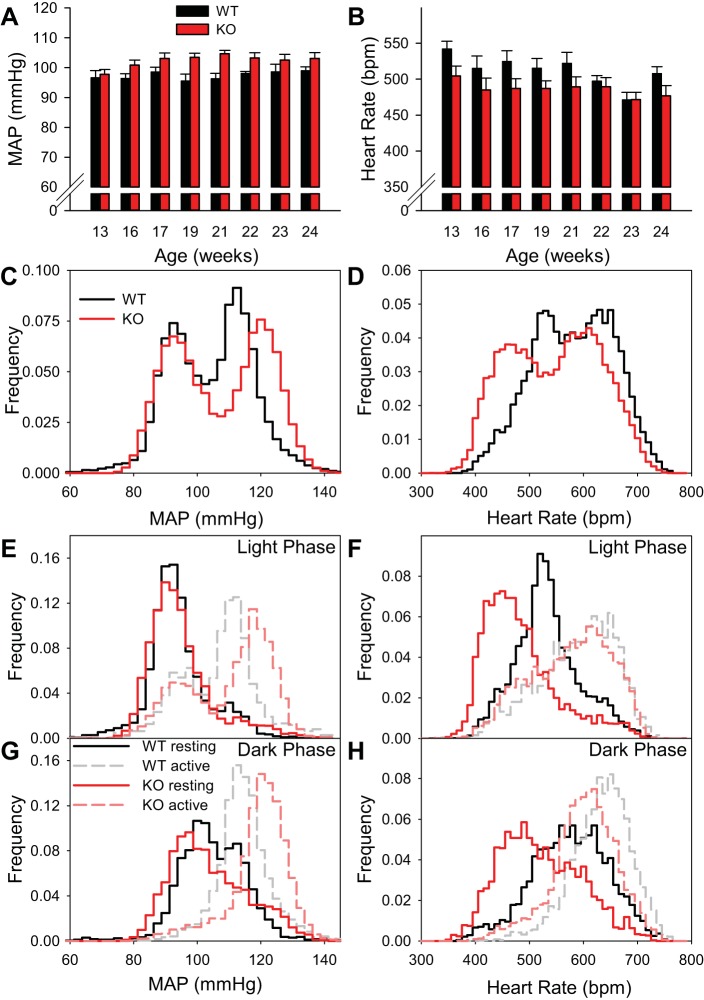

In telemetered mice studied from 13 to 24 wk of age, body weight increased more in Brs3−/y (from 29.3 ± 1.0 to 35.9 ± 0.9 g) than control mice (from 24.3 ± 0.8 to 26.3 ± 0.8 g; P = 0.002 for genotype effect on body weight gain). Despite the weight changes, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate were stable within each genotype from 13 to 24 wk of age (Fig. 1, A and B).

Fig. 1.

Conscious Brs3−/y mice have a reduced resting heart rate and an activity-dependent increase in mean arterial pressure (MAP). A and B: light-phase MAP and heart rate from 13 to 24 wk of age in the same cohort of mice. Data at each age are from a weekday 2 h undisturbed interval early in the light phase. C and D: histograms of MAP and heart rate during 1-min intervals. For statistical analysis, the cumulative frequency percentiles for each mouse were compared (n = 5–6/group). MAPs in percentiles 57–80 were higher and all heart rate percentiles were lower (P < 0.05 by t-test without multiplicity correction). E and F: light-phase MAP and heart rate histograms for physically inactive and active intervals. In wild-type (WT) and Brs3−/y (KO) mice, 26% and 34% of intervals were active, respectively. G and H: dark-phase MAP and heart rate histograms for inactive and active intervals. Active intervals were 66% for both genotypes. In C–H, data are the same 48 h in 13-wk old mice as in Table 1. Histogram bins are 2.5 mmHg for MAP and 10 beats/min for heart rate.

Free-living telemetered Brs3−/y mice had an elevated (∼3 mmHg) systolic, diastolic, and MAP in the light phase, with no difference from controls during the dark phase (Table 1). Heart rate was lower in Brs3−/y mice in both the dark (−40 beats/min) and light (−29 beats/min) phases. Physical activity in Brs3−/y mice was greater than wild-type mice only during the light phase.

Table 1.

Blood pressure, heart rate, and activity in wild-type and Brs3−/y mice

| Phase | Wild Type | Brs3−/y | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 24.3 ± 0.8 | 29.3 ± 1.0 | 0.004 | |

| MAP, mmHg | Light | 96.3 ± 0.3 | 99.3 ± 0.5 | 0.001 |

| Dark | 110.3 ± 1.5 | 112.8 ± 1.4 | 0.26 | |

| Systolic pressure, mmHg | Light | 109.5 ± 0.6 | 112.5 ± 1.1 | 0.055 |

| Dark | 124.2 ± 2.1 | 127.2 ± 1.7 | 0.30 | |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg | Light | 81.9 ± 0.5 | 85.3 ± 0.9 | 0.01 |

| Dark | 96.0 ± 1.7 | 98.0 ± 1.7 | 0.43 | |

| Heart rate, beats/min | Light | 542 ± 11 | 513 ± 9 | 0.06 |

| Dark | 609 ± 7 | 569 ± 5 | 0.001 | |

| Activity, AU | Light | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 0.04 |

| Dark | 15.8 ± 0.8 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 0.35 |

Data are means ± SE of the individual means; n = 5–6 mice/group. Hemodynamic parameters were measured by radiotelemetry in 13-wk-old conscious mice as 1-min averages for 48 continuous hours during the weekend, a quiet period in the vivarium. MAP, mean arterial pressure; AU, arbitrary units.

The MAP and heart rate frequency distributions were each bimodal, with a larger span in the Brs3−/y mice (Fig. 1, C and D). To understand this variation, the light/dark phases and physically active/inactive intervals were analyzed separately (Fig. 1, E–H). The resting MAP was similar in Brs3−/y and control mice, but increased more with activity in Brs3−/y mice. The resting heart rate was lower in Brs3−/y mice and also increased more with activity, reaching close to the same level as wild-type mice. Statistical models demonstrated that both genotype and genotype × activity interaction (both P < 0.0001) contribute to predicting both MAP and heart rate (Table 2). Consistent with the wider range in heart rate, the standard deviation of the RR intervals was greater in Brs3−/y mice (17.4 ± 1.7 vs. 11.8 ± 2.4 ms, P = 0.001). However, the percentage of consecutive RR intervals differing by >6 ms (pNN6), a measure of cardiac parasympathetic activity (51), was the same in wild-type and Brs3−/y mice (17.2 ± 3.0 vs. 18.9 ± 4.8%, respectively).

Table 2.

Models of MAP and heart rate

| MAP |

Heart Rate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate (SE) | t Ratio | Prob> t | Estimate (SE) | t Ratio | Prob> t |

| Light phase | ||||||

| Intercept | 97.10 (0.09) | 1127 | <0.0001 | 523.3 (0.5) | 982 | <0.0001 |

| Activity | 11.92 (0.15) | 80 | <0.0001 | 60.8 (0.9) | 66 | <0.0001 |

| Genotype | 0.67 (0.09) | 8 | <0.0001 | −19.1 (0.5) | −36 | <0.0001 |

| Genotype × activity | 0.60 (0.15) | 4 | <0.0001 | 14.1 (0.9) | 15 | <0.0001 |

| Dark phase | ||||||

| Intercept | 106.64 (0.10) | 1055 | <0.0001 | 561.1 (0.6) | 890 | <0.0001 |

| Activity | 7.84 (0.10) | 78 | <0.0001 | 44.0 (0.6) | 71 | <0.0001 |

| Genotype | 1.35 (0.08) | 17 | <0.0001 | −19.3 (0.5) | −39 | <0.0001 |

| Genotype × activity | 1.88 (0.10) | 19 | <0.0001 | 7.3 (0.6) | 12 | <0.0001 |

Standard least-squares models for MAP and heart rate were constructed separately for the light and dark phases, with the activity [as log(activity +0.5)] and genotype (wild type vs. Brs3−/y) and their interaction as fixed effects, using the same data as in Table 1. The adjusted r2 are 0.32 (light, MAP), 0.31 (dark, MAP), 0.28 (light, heart rate), and 0.30 (dark, heart rate). SE, standard error.

Baroreceptor sensitivity (17, 30) was investigated using the sequence method during a 1-h light phase interval and was not different in wild-type vs. Brs3−/y mice under a variety of analysis parameters (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovagal baroreceptor reflex sensitivity

| Delay, heartbeats | Wild Type, ms/mmHg | Brs3−/y, ms/mmHg | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRSup | 0 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 0.50 |

| 1 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 0.44 | |

| 2 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.31 | |

| BRSdown | 0 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.92 |

| 1 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.79 | |

| 2 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.52 |

Baroreceptor sensitivity (ms/mmHg) was measured in 1 h of the light phase by sequence analysis of episodes with increasing (BRSup) and decreasing (BRSdown) blood pressure as detailed in materials and methods. Delay is of 0, 1, or 2 heartbeats using intervals with increasing or decreasing blood pressure and RR interval, as indicated. n = 5–6/group.

Intrinsic heart rate.

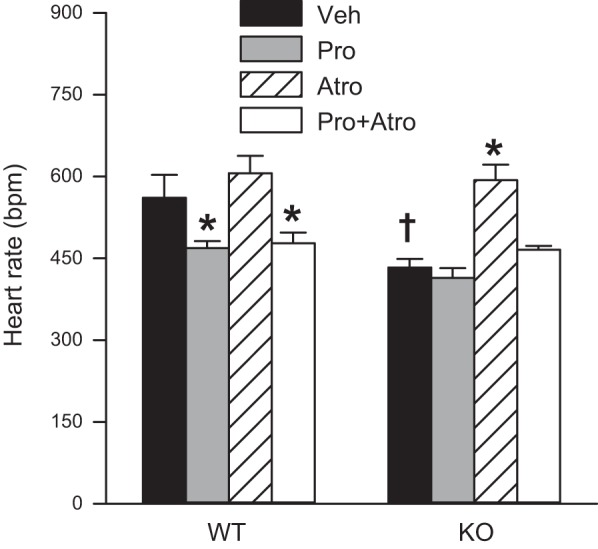

The heart rate of the Brs3−/y mice increased more than control mice when parasympathetic input was inhibited with the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine, with both groups reaching similar posttreatment levels (Fig. 2, 31–45 min after dosing; 16–30 min after dosing was quantitatively similar, not shown). Sympathetic inhibition with the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol reduced the higher heart rate of the control mice to the level of the Brs3−/y mice and had no effect in Brs3−/y mice. The intrinsic heart rate, measured after blockade of both sympathetic and parasympathetic signals with propranolol and atropine, was similar in Brs3−/y and control mice. Taken together, these data suggest that the lower heart rate in Brs3−/y mice is due to reduced sympathetic (and/or increased parasympathetic) drive to the heart.

Fig. 2.

Conscious Brs3−/y mice have a reduced response to propranolol and a normal intrinsic heart rate. Heart rate 31 to 45 min after treatment with vehicle (Veh, saline), propranolol (Pro, 5 mg/kg ip), atropine (Atro, 1 mg/kg ip), or propranolol plus atropine (Pro + Atro). WT, wild-type controls; KO, Brs3−/y mice. Data are means ± SE; n = 4–6/group. *P < 0.05, Pro or Atro or Pro + Atro vs. vehicle within genotype; †P < 0.05, WT vs. KO within treatment. Experiment is a crossover design with mice age 19–23 wk.

Cardiovascular Effects of the BRS-3 Agonist MK-5046

Studies in conscious mice.

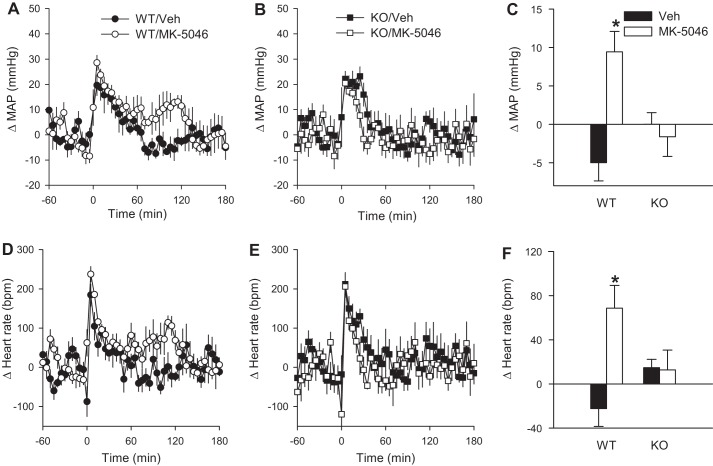

The effects of single intraperitoneal injections of the BRS-3 agonist MK-5046 on MAP and heart rate of conscious mice are presented in Fig. 3. The increase in MAP and heart rate caused by handling was intact in the Brs3−/y mice, being similar to controls (Fig. 4, A, B, D, and E). Whereas the handling masked any early effects of MK-5046, in the second hour after treatment BRS-3 activation was associated with significantly increased MAP (by 9 ± 3 mmHg) and heart rate (by 69 ± 21 beats/min) in wild-type mice (Fig. 3, A, C, D, and F). In contrast, MK-5046 had no effect on MAP or heart rate in Brs3−/y mice, demonstrating that the increase in MAP and heart rate is mediated by MK-5046 acting on its intended target, BRS-3 (Fig. 3, B, C, E, and F).

Fig. 3.

MK-5046 increases MAP and heart rate. The MAP (A–C) and heart rate (D–F) response to MK-5046 (3 mg/kg ip) or vehicle (saline) was studied in conscious wild-type (WT) and Brs3−/y (KO) mice at 16–17 wk of age. Data are change from the baseline, 120 to 1 min before treatment. C and F: mean change in MAP and heart rate at 61–120 min postinjection. Baseline MAPs were 98 ± 1 (WT/Veh), 97 ± 2 (WT/MK-5046), 102 ± 2 (KO/Veh), and 102 ± 2 (KO/MK-5046) mmHg. Baseline heart rates were 526 ± 16 (WT/Veh), 513 ± 16 (WT/MK-5046), 482 ± 15 (KO/Veh), and 490 ± 15 (KO/MK-5046) beats/min. Data are means ± SE; n = 5–6/group. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

Fig. 4.

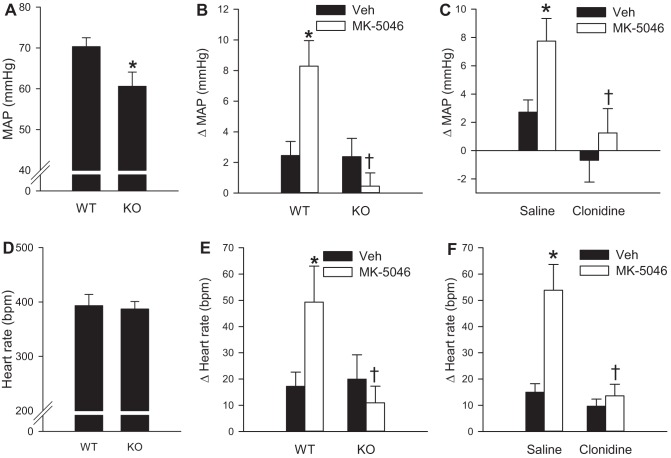

Clonidine attenuates the increase in MAP and heart rate caused by MK-5046. Effects of intravenous MK-5046 (1 mg/kg in 5% dimethylacetamide in saline) were studied in anesthetized wild-type (WT) and Brs3−/y (KO) mice at 12–16 wk of age. A and D: baseline MAP and heart rate from 12 to 2 min before infusion. *P < 0.05 vs. WT. B and E: change in MAP and heart rate response to MK-5046 or vehicle (Veh) at 1 to 5 min after infusion. *P < 0.05 MK-5046 vs. vehicle; †P < 0.05, genotype effect within MK-5046 treatment. C and F: in wild-type mice, effect of pretreatment with clonidine (40 μg/kg ip) or saline given 1 h before MK-5046 on MAP and heart rate response to MK-5046 or vehicle (Veh) at 1 to 5 min after infusion. Data are means ± SE; n = 6–7/group. *P < 0.05 MK-5046 vs. vehicle; †P < 0.05, clonidine effect within MK-5046 treatment.

Studies in anesthetized mice.

We next explored hemodynamics in pentobarbital sodium-anesthetized mice to assess the acute effects of BRS-3 activation on blood pressure and heart rate, which were partially masked in conscious mice due to the confounding effects of activity and handling. Similar to the results in conscious mice, intravenous MK-5046 (1 mg/kg) increased MAP by 8 ± 2 mmHg and heart rate by 49 ± 14 beats/min in wild-type mice (Fig. 4, B and E). The increases in MAP and heart rate were short-lived, lasting ∼5 min. Again, MK-5046 had no significant effect on MAP or heart rate in Brs3−/y mice, demonstrating that the effects in control mice are mediated by BRS-3. In contrast to the results in conscious mice, anesthetized Brs3−/y mice had a 7 mmHg lower MAP than controls (60.6 ± 3.5 vs. 70.3 ± 2.2 mmHg, P = 0.02) (Fig. 4A). There was no difference in heart rate (393 ± 21 beats/min in Brs3−/y vs. 387 ± 14 beats/min in controls, P = 0.26) (Fig. 4D).

Effect of clonidine on MK-5046-mediated actions.

To study a possible role of the sympathetic nervous system in the cardiovascular changes caused by MK-5046, we assessed the effects of clonidine, a centrally acting sympatholytic α2-adrenergic agonist (22). Clonidine alone had no significant effect on MAP or heart rate in anesthetized wild-type mice (Fig. 4, C and F), likely reflecting the reduced sympathetic drive of the anesthetized state (19, 32). However, clonidine pretreatment completely abolished the effect of MK-5046 to increase MAP and heart rate, consistent with a sympathetic mechanism.

Central infusion of MK-5046.

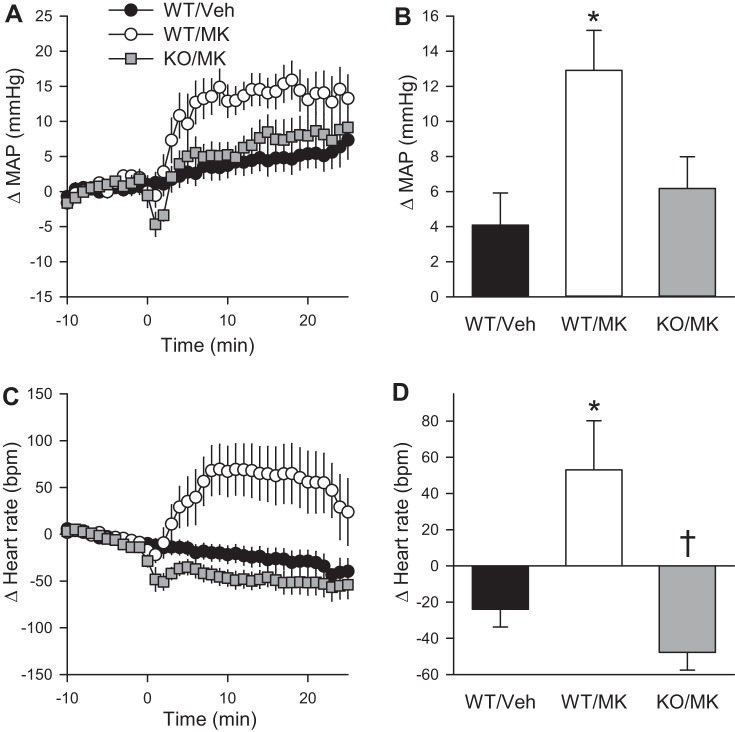

To test directly if the MAP and heart rate effects of MK-5046 occur through the central nervous system, we bilaterally implanted cannulas into the anterior hypothalamus. This region has a high level of BRS-3 expression and ligand binding (14), and several nuclei in this region are implicated in cardiovascular regulation (5, 39). Infusion of MK-5046 increased both MAP and heart rate significantly more than vehicle in wild-type mice, while central infusion of MK-5046 had no effect in Brs3−/y mice (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Central MK-5046 increases MAP and heart rate. Effect of intrahypothalamic MK-5046 (2 μg total) in anesthetized wild-type (WT) and Brs3−/y (KO) mice. A and C: changes from baseline (12 to 2 min before infusion) in MAP and heart rate, respectively. B and D: mean change from baseline at 2–25 min after infusion. Baseline MAPs were 66 ± 4 (WT/Veh), 70 ± 3 (WT/MK), and 65 ± 3 (KO/MK) mmHg. Baseline heart rates were 337 ± 9 (WT/Veh) 313 ± 10 (WT/MK) and 339 ± 22 (KO/MK) beats/min. Data are means ± SE; n = 6–12/group. *P < 0.05, MK-5046 vs. vehicle within genotype; †P < 0.05, WT vs. KO within treatment.

DISCUSSION

BRS-3 regulates energy homeostasis, but its role in blood pressure and heart rate control has been unclear. We show that despite mild obesity, Brs3−/y mice are not hypertensive in the resting state and exhibit a normal intrinsic heart rate. We also establish for the first time that BRS-3 activation with a selective, brain-penetrant agonist causes an on-target, BRS-3 mechanism-based increase in MAP and heart rate.

Previously, Brs3−/y mice were reported to have an unchanged heart rate (of ∼700 beats/min) and an increased MAP (by 19 mmHg) in old, but not young, mice (41). In contrast, using telemetry in free-living mice, we demonstrate a reduced resting heart rate and an exaggerated increase with physical activity that reaches a maximum approaching that of controls. Similarly, the apparently elevated blood pressure in the Brs3−/y mice is attributed to an exaggerated MAP increase with physical activity and not an inherently high resting blood pressure. The MAP and heart rate did not change with age. Thus the prior results measured by tail cuff (41), which can increase heart rate and MAP (13, 26, 55), match our data during physical activity, and our analysis demonstrates a significant genotype × activity interaction. A model to explain these results is that a primary reduction in heart rate in Brs3−/y mice elicits compensatory mechanisms to defend blood pressure, presumably including the intact baroreceptor reflex. Activity-induced increases in heart rate and blood pressure are intact in Brs3−/y mice, indicating that BRS-3 does not have a role in these processes.

The cardiovascular system is regulated by both parasympathetic and sympathetic tone (10). In conscious Brs3−/y mice, the reduced resting heart rate and attenuated reduction by propranolol suggest that the sympathetic tone to the heart is reduced. An increase in parasympathetic tone seems less likely from the effect of the sympatholytic drug clonidine on MK-5046 action in wild-type mice. In addition, we have shown that MK-5046 increases temperature in brown adipose tissue, likely reflecting a role for BRS-3 in sympathetic activation of thermogenesis (28). Despite the reduced basal sympathetic tone, the response to physical activity in Brs3−/y mice is exaggerated, suggesting that BRS-3 contributes to setting the resting sympathetic tone but not the activity-induced increase in heart rate and MAP.

BRS-3 action is likely mediated via a central mechanism since delivery of MK-5046 in the brain increases MAP and heart rate, and the effects of peripheral MK-5046 are abolished by clonidine, a centrally acting sympatholytic. BRS-3 is present in brain regions that regulate blood pressure and heart rate (2, 11, 16), including the medial preoptic, posterior hypothalamic, dorsomedial hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray, dorsal raphe, parabrachial nucleus, and nucleus of the solitary tract (14, 31, 54). Modulation of other central antiobesity mechanisms (leptin, melanocortin, and ghrelin) can also increase blood pressure. For example, MC4R-deficient mice and humans are obese in the absence of hypertension (12, 50), and the central MC4R agonist, α-MSH, increases blood pressure and heart rate (8, 35). Recently, a central role for the leptin pathway was demonstrated in obesity-associated hypertension (49). At this time it is unknown how or if BRS-3 interacts with these mechanisms. Similarly, it is also unknown how or if BRS-3 interacts with other cardiovascular regulators, such as vasopressin and the renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone cascades.

We did not directly measure cardiac output or peripheral vascular resistance. However, cardiac output can be estimated from the heart rate (43), since in very small animals the upper end of the heart rate range is limited, restricting changes in stroke volume (26). Making these assumptions, the 13% increase in heart rate caused by MK-5046 in conscious wild-type mice is calculated (25) to produce a 12% increase in cardiac output. Since the measured MAP increased in proportion to the calculated cardiac output, this suggests that no major changes in peripheral vascular resistance occurred. This hypothesis requires confirmation by direct experiment.

The on-target effects of MK-5046 in mice suggest that clinical adverse events, including transiently increased blood pressure, erections, and feeling hot, cold, and/or jittery (46), may be mechanism-based (i.e., due to BRS-3 activation) and result from sympathetic stimulation. It is unclear why no heart rate increase was observed clinically; possibilities include insufficient statistical power and masking by a reflex bradycardia elicited by the increase in blood pressure. It is unknown if this hypertensive effect of MK-5046 would be more pronounced in elderly or patients with diminished baroreflex function. The adverse effects of BRS-3 agonists attenuate with continued dosing (14, 37, 46). We have not investigated attenuation in mice, making this an important question for future studies. Mechanism-based adverse hemodynamic effects are unacceptable in pharmacological treatment for obesity, and it is unclear if attenuation could be used to mitigate this problem. MK-5046 has different activation properties than a BRS-3 peptide ligand (38), suggesting that partial or biased (52) BRS-3 agonists may exist. Discovery of a BRS-3 ligand with anti-obesity but not cardiovascular activities would be welcome.

GRANTS

This research was supported by NIDDK Intramural Research Program Grants DK-075057 and DK-075063, and by NHLBI Grant 5-P01-HL-56693 (A. Diedrich).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: D.M.L., J.S., and M.L.R. conception and design of research; D.M.L. and C.X. performed experiments; D.M.L., R.J.B., A.D., and M.L.R. analyzed data; D.M.L., R.J.B., and M.L.R. interpreted results of experiments; D.M.L. and M.L.R. prepared figures; D.M.L. and M.L.R. drafted manuscript; D.M.L., C.X., R.J.B., A.D., J.S., and M.L.R. approved final version of manuscript; C.X., A.D., J.S., and M.L.R. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Oksana Gavrilova, Xiongce Zhao, and Yuning George Huang, of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), for advice and suggestions and Danielle Springer, Audrey Noguchi, and Michelle Allen of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Murine Phenotyping Core for collaboration on the conscious telemetry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Badea A, Ali-Sharief AA, Johnson GA. Morphometric analysis of the C57BL/6J mouse brain. Neuroimage 37: 683–693, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair ML, Mickelsen D. Activation of lateral parabrachial nucleus neurons restores blood pressure and sympathetic vasomotor drive after hypotensive hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R742–R750, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brede M, Braeuninger S, Langhauser F, Hein L, Roewer N, Stoll G, Kleinschnitz C. alpha2-Adrenoceptors do not mediate neuroprotection in acute ischemic stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: E1–E7, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Civelli O, Reinscheid RK, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB. G protein-coupled receptor deorphanizations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 53: 127–146, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culman J, Unger T. Central mechanisms regulating blood pressure: circuits and transmitters. Eur Heart J 13, Suppl A: 10–17, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension 52: 818–827, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Sowers JR. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10: 364–376, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunbar JC, Lu H. Proopiomelanocortin (POMC) products in the central regulation of sympathetic and cardiovascular dynamics: studies on melanocortin and opioid interactions. Peptides 21: 211–217, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman JV, Dewey FE, Hadley DM, Myers J, Froelicher VF. Autonomic nervous system interaction with the cardiovascular system during exercise. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 48: 342–362, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradin K, Qadri F, Nomikos GG, Hillegaart V, Svensson TH. Substance P injection into the dorsal raphe increases blood pressure and serotonin release in hippocampus of conscious rats. Eur J Pharmacol 218: 363–367, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenfield JR, Miller JW, Keogh JM, Henning E, Satterwhite JH, Cameron GS, Astruc B, Mayer JP, Brage S, See TC, Lomas DJ, O'Rahilly S, Farooqi IS. Modulation of blood pressure by central melanocortinergic pathways. N Engl J Med 360: 44–52, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross V, Luft FC. Exercising restraint in measuring blood pressure in conscious mice. Hypertension 41: 879–881, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan XM, Chen H, Dobbelaar PH, Dong Y, Fong TM, Gagen K, Gorski J, He S, Howard AD, Jian T, Jiang M, Kan Y, Kelly TM, Kosinski J, Lin LS, Liu J, Marsh DJ, Metzger JM, Miller R, Nargund RP, Palyha O, Shearman L, Shen Z, Stearns R, Strack AM, Stribling S, Tang YS, Wang SP, White A, Yu H, Reitman ML. Regulation of energy homeostasis by bombesin receptor subtype-3: selective receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity. Cell Metab 11: 101–112, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan XM, Metzger JM, Yang L, Raustad KA, Wang SP, Spann SK, Kosinski JA, Yu H, Shearman LP, Faidley TD, Palyha O, Kan Y, Kelly TM, Sebhat I, Lin LS, Dragovic J, Lyons KA, Craw S, Nargund RP, Marsh DJ, Strack AM, Reitman ML. Antiobesity effect of MK-5046, a novel bombesin receptor subtype-3 agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336: 356–364, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 335–346, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilzendeger AM, Goncalves AC, Plehm R, Diedrich A, Gross V, Pesquero JB, Bader M. Autonomic dysregulation in ob/ob mice is improved by inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme. J Mol Med 88: 383–390, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holobotovskyy V, Manzur M, Tare M, Burchell J, Bolitho E, Viola H, Hool LC, Arnolda LF, McKitrick DJ, Ganss R. Regulator of G-protein signaling 5 controls blood pressure homeostasis and vessel wall remodeling. Circ Res 112: 781–791, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen BJ, De Celle T, Debets JJ, Brouns AE, Callahan MF, Smith TL. Effects of anesthetics on systemic hemodynamics in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1618–H1624, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennings CA, Harrison DC, Maycox PR, Crook B, Smart D, Hervieu GJ. The distribution of the orphan bombesin receptor subtype-3 in the rat CNS. Neuroscience 120: 309–324, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen RT, Battey JF, Spindel ER, Benya RV. International Union of Pharmacology. LXVIII. Mammalian bombesin receptors: nomenclature, distribution, pharmacology, signaling, and functions in normal and disease states. Pharmacol Rev 60: 1–42, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan ZP, Ferguson CN, Jones RM. Alpha-2 and imidazoline receptor agonists. Their pharmacology and therapeutic role. Anaesthesia 54: 146–165, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HW, Uh DK, Yoon SY, Roh DH, Kwon YB, Han HJ, Lee HJ, Beitz AJ, Lee JH. Low-frequency electroacupuncture suppresses carrageenan-induced paw inflammation in mice via sympathetic post-ganglionic neurons, while high-frequency EA suppression is mediated by the sympathoadrenal medullary axis. Brain Res Bull 75: 698–705, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SM, Eisner C, Faulhaber-Walter R, Mizel D, Wall SM, Briggs JP, Schnermann J. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in NKCC1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1230–F1238, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreissl MC, Wu HM, Stout DB, Ladno W, Schindler TH, Zhang X, Prior JO, Prins ML, Chatziioannou AF, Huang SC, Schelbert HR. Noninvasive measurement of cardiovascular function in mice with high-temporal-resolution small-animal PET. J Nucl Med 47: 974–980, 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurtz TW, Griffin KA, Bidani AK, Davisson RL, Hall JE. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. II. Blood pressure measurement in experimental animals: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association council on high blood pressure research. Hypertension 45: 299–310, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladenheim EE, Hamilton NL, Behles RR, Bi S, Hampton LL, Battey JF, Moran TH. Factors contributing to obesity in bombesin receptor subtype-3-deficient mice. Endocrinology 149: 971–978, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lateef DM, Abreu-Vieira G, Xiao C, Reitman ML. Regulation of body temperature and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by bombesin receptor subtype-3. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E681–E687, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lateef DM, Xiao C, Reitman ML. Search for an endogenous bombesin-like receptor 3 (BRS-3) ligand using parabiotic mice. PLoS One 10: e0142637, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laude D, Baudrie V, Elghozi JL. Tuning of the sequence technique. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag 28: 30–34, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Lao ZJ, Zhang J, Schaeffer MT, Jiang MM, Guan XM, Van der Ploeg LH, Fong TM. Molecular basis of the pharmacological difference between rat and human bombesin receptor subtype-3 (BRS-3). Biochemistry 41: 8954–8960, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maignan E, Dong WX, Legrand M, Safar M, Cuche JL. Sympathetic activity in the rat: effects of anaesthesia on noradrenaline kinetics. J Auton Nerv Syst 80: 46–51, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majumdar ID, Weber HC. Biology and pharmacology of bombesin receptor subtype-3. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 19: 3–7, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantey SA, Weber HC, Sainz E, Akeson M, Ryan RR, Pradhan TK, Searles RP, Spindel ER, Battey JF, Coy DH, Jensen RT. Discovery of a high affinity radioligand for the human orphan receptor, bombesin receptor subtype 3, which demonstrates that it has a unique pharmacology compared with other mammalian bombesin receptors. J Biol Chem 272: 26062–26071, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumura K, Tsuchihashi T, Abe I, Iida M. Central alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone acts at melanocortin-4 receptor to activate sympathetic nervous system in conscious rabbits. Brain Res 948: 145–148, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumura K, Tsuchihashi T, Fujii K, Abe I, Iida M. Central ghrelin modulates sympathetic activity in conscious rabbits. Hypertension 40: 694–699, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metzger JM, Gagen K, Raustad KA, Yang L, White A, Wang SP, Craw S, Liu P, Lanza T, Lin LS, Nargund RP, Guan XM, Strack AM, Reitman ML. Body temperature as a mouse pharmacodynamic response to bombesin receptor subtype-3 agonists and other potential obesity treatments. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E816–E824, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno P, Mantey SA, Nuche-Berenguer B, Reitman ML, Gonzalez N, Coy DH, Jensen RT. Comparative pharmacology of bombesin receptor subtype-3, nonpeptide agonist MK-5046, a universal peptide agonist, and peptide antagonist Bantag-1 for human bombesin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347: 100–116, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morpurgo C. Pharmacological modifications of sympathetic responses elicited by hypothalamic stimulation in the rat. Br J Pharmacol 34: 532–542, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohki-Hamazaki H, Wada E, Matsui K, Wada K. Cloning and expression of the neuromedin B receptor and the third subtype of bombesin receptor genes in the mouse. Brain Res 762: 165–172, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohki-Hamazaki H, Watase K, Yamamoto K, Ogura H, Yamano M, Yamada K, Maeno H, Imaki J, Kikuyama S, Wada E, Wada K. Mice lacking bombesin receptor subtype-3 develop metabolic defects and obesity. Nature 390: 165–169, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelat M, Dessy C, Massion P, Desager JP, Feron O, Balligand JL. Rosuvastatin decreases caveolin-1 and improves nitric oxide-dependent heart rate and blood pressure variability in apolipoprotein E−/− mice in vivo. Circulation 107: 2480–2486, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips D, Covian R, Aponte AM, Glancy B, Taylor JF, Chess D, Balaban RS. Regulation of oxidative phosphorylation complex activity: effects of tissue-specific metabolic stress within an allometric series and acute changes in workload. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R1034–R1048, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahmouni K. Obesity-associated hypertension: recent progress in deciphering the pathogenesis. Hypertension 64: 215–221, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahmouni K, Morgan DA, Morgan GM, Mark AL, Haynes WG. Role of selective leptin resistance in diet-induced obesity hypertension. Diabetes 54: 2012–2018, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitman ML, Dishy V, Moreau A, Denney WS, Liu C, Kraft WK, Mejia AV, Matson MA, Stoch SA, Wagner JA, Lai E. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of MK-5046, a bombesin receptor subtype-3 (BRS-3) agonist, in healthy patients. J Clin Pharmacol 52: 1306–1316, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sebhat IK, Franklin C, Lo MC, Chen D, Jewell JP, Miller R, Pang J, Palyha O, Kan Y, Kelly TM, Guan XM, Marsh DJ, Kosinski JA, Metzger JM, Lyons K, Dragovic J, Guzzo PR, Henderson AJ, Reitman ML, Nargund RP, Wyvratt MJ, Lin LS. Discovery of MK-5046, a potent, selective bombesin receptor subtype-3 agonist for the treatment of obesity. ACS Med Chem Lett 2: 43–47, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shek EW, Brands MW, Hall JE. Chronic leptin infusion increases arterial pressure. Hypertension 31: 409–414, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simonds SE, Pryor JT, Ravussin E, Greenway FL, Dileone R, Allen AM, Bassi J, Elmquist JK, Keogh JM, Henning E, Myers MG Jr, Licinio J, Brown RD, Enriori PJ, O'Rahilly S, Sternson SM, Grove KL, Spanswick DC, Farooqi IS, Cowley MA. Leptin mediates the increase in blood pressure associated with obesity. Cell 159: 1404–1416, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tallam LS, Stec DE, Willis MA, da Silva AA, Hall JE. Melanocortin-4 receptor-deficient mice are not hypertensive or salt-sensitive despite obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperleptinemia. Hypertension 46: 326–332, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thireau J, Zhang BL, Poisson D, Babuty D. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Exp Physiol 93: 83–94, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Violin JD, Crombie AL, Soergel DG, Lark MW. Biased ligands at G-protein-coupled receptors: promise and progress. Trends Pharmacol Sci 35: 308–316, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu X, Coats JK, Yang CF, Wang A, Ahmed OM, Alvarado M, Izumi T, Shah NM. Modular genetic control of sexually dimorphic behaviors. Cell 148: 596–607, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang L, Parks GS, Wang Z, Wang L, Lew M, Civelli O. Anatomical characterization of bombesin receptor subtype-3 mRNA expression in the rodent central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 521: 1020–1039, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao X, Ho D, Gao S, Hong C, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Arterial pressure monitoring in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 1: 105–122, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]