Abstract

The cerebral blood flow is tightly regulated by myogenic, endothelial, metabolic, and neural mechanisms under physiological conditions, and a large body of recent evidence indicates that inflammatory pathways have a major influence on the cerebral blood perfusion in certain central nervous system disorders, like hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, and vascular dementia. All major cell types involved in cerebrovascular control pathways (i.e., smooth muscle, endothelium, neurons, astrocytes, pericytes, microglia, and leukocytes) are capable of synthesizing endocannabinoids and/or express some or several of their target proteins [i.e., the cannabinoid 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) receptors and the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 ion channel]. Therefore, the endocannabinoid system may importantly modulate the regulation of cerebral circulation under physiological and pathophysiological conditions in a very complex manner. Experimental data accumulated since the late 1990s indicate that the direct effect of cannabinoids on cerebral vessels is vasodilation mediated, at least in part, by CB1 receptors. Cannabinoid-induced cerebrovascular relaxation involves both a direct inhibition of smooth muscle contractility and a release of vasodilator mediator(s) from the endothelium. However, under stress conditions (e.g., in conscious restrained animals or during hypoxia and hypercapnia), cannabinoid receptor activation was shown to induce a reduction of the cerebral blood flow, probably via inhibition of the electrical and/or metabolic activity of neurons. Finally, in certain cerebrovascular pathologies (e.g., subarachnoid hemorrhage, as well as traumatic and ischemic brain injury), activation of CB2 (and probably yet unidentified non-CB1/non-CB2) receptors appear to improve the blood perfusion of the brain via attenuating vascular inflammation.

Keywords: cerebral circulation, endocannabinoids, cannabinoid receptors, TRPV1 channel, neurovascular unit

the cerebral vasculature has two main homeostatic functions: 1) to adjust the local blood supply to the eventually rapidly changing metabolic demands of neurons; and 2) to maintain an optimal extracellular environment in the brain. The former function is realized by the regulation of the local cerebral blood flow (CBF), whereas the latter is achieved by the maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and related transport mechanisms. The endocannabinoid system has been implicated as an important regulatory component in both of these cerebrovascular functions. The roles of endocannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors in the BBB have been reviewed recently (237). Here we aim to overview our knowledge on the endocannabinoid-mediated regulation of cerebral circulation.

Regulatory Mechanisms of the Cerebral Circulation

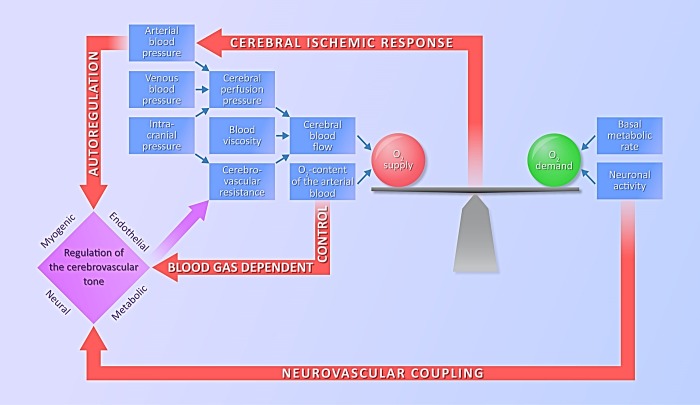

A continuous oxygen supply is essential for the normal functions of the central nervous system (CNS), as hypoxia may result in altered neuronal functions within seconds and permanent neuronal damage within minutes. Therefore, it is not surprising that the CBF is tightly controlled, mainly by feed-forward type regulatory pathways, which are activated before the development of an imbalance between cerebral oxygen demand and supply. In this way, disturbances of the cardiorespiratory system, which may potentially alter the oxygen supply of the brain [e.g., changes in blood pressure (BP) or blood-gas tensions] directly evoke cerebrovascular counterregulatory responses (Fig. 1). In addition, increased neuronal activity, associated with elevated oxygen demand, directly stimulates the powerful neurovascular regulatory system, which increases the oxygen supply to neurons before they become hypoxic. In case of the exhaustion of the feed-forward regulatory pathways, a feed-back type homeostatic reaction, the “cerebral ischemic response” or “Cushing-reflex” develops, resulting in a marked increase of the systemic BP (Fig. 1). Here we give a brief overview of cerebrovascular control mechanisms to introduce the potential targets of cannabinoid actions in the cerebral circulation.

Fig. 1.

Regulatory pathways of the cerebral circulation. A continuous balance between the oxygen demand and oxygen supply of the brain is essential for physiological neuronal functions. Cerebrovascular resistance is tightly regulated by myogenic, endothelial, metabolic, and neural mechanisms in response to changes in neuronal activity or disturbances of the cardiorespiratory system. In case of an imbalance between the oxygen demand and supply, the cerebral ischemic response (Cushing reflex) is activated and increases the perfusion pressure of the brain.

Regulatory pathways activated by disturbances of the cardiorespiratory system.

AUTOREGULATION OF THE CBF.

Autoregulation is the ability of the cerebral vessels to maintain constant CBF, despite changes in the systemic arterial BP within the range of 60–150 mmHg, thereby ensuring a steady, optimal level of blood supply to the brain (175). If BP falls outside this range, at either its lower or upper limit, autoregulatory mechanisms become insufficient to further maintain a stable blood flow. CBF autoregulation involves either the transient responses of the BP-CBF relationship (during cardiac cycle-related fluctuations of the BP), or the responses to sudden changes in the mean BP (related, e.g., to changes in posture or intrathoracal pressure, like in severe coughing as well as during Müller or Valsalva maneuvers) (43, 169). Mechanisms involved in CBF autoregulation are complex and include myogenic, metabolic, endothelial, and neuronal components (116, 175, 184, 202) (Fig. 1).

The myogenic mechanism of autoregulation is based on the Bayliss phenomenon (14, 73) and represents the fastest response to changes in BP to maintain a stable CBF. It was shown in rat cerebral arteries and arterioles that, at elevated intravascular pressures, vasoconstriction developed, whereas, at decreased intravascular pressures, vasodilation developed (23, 161). Increased intraluminal arterial pressure results in an increased stress of the vessel wall, which opens mechanosensitive cation channels (88, 254). The consequent depolarization opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and Ca2+ influx causes cerebral vasoconstriction. The activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels appears to be essential for myogenic contraction in rat cerebral arteries (142). Recently it has been proposed that not only intraluminar pressure, but also increased flow rate, may result in contraction of the cerebrovascular smooth muscle (24, 25) and, therefore, contribute to cerebrovascular autoregulation (116). Although the exact mechanism of this vascular reaction is not completely understood, the involvement of the cytoskeletal matrix, integrins, and vasoconstrictor arachidonic acid (AA) metabolites has been implicated (24, 228).

The concept of metabolic autoregulation of the CBF dates back to the late 1800s, when Roy and Sherrington (198) hypothesized that the brain possesses an intrinsic mechanism by which CBF can be controlled locally via vasodilatory properties of the chemical compounds released in association with increased neuronal activity and metabolism (e.g., adenosine, H+, lactate, K+) (203). On the other hand, the concentration of these vasoactive compounds also depends on the level of CBF, which washes them out from the brain tissue. Therefore, at the lower limit of autoregulation, an increase, whereas, at the upper limit of autoregulation, a decrease in the concentration of these vasodilator substances aids the maintenance of a stable CBF.

The endothelium also plays an important role in cerebral autoregulation (100). With regard to the vasoconstriction that develops in response to increased intravascular pressure, it was demonstrated already in the mid-1980s that removal of the endothelium inhibits pressure-dependent smooth muscle depolarization, action potential generation, and constriction in the middle cerebral arteries, indicating a potential mechanotransducer role of the endothelium in the autoregulatory response to pressure (88, 89, 110). However, the role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) in the maintenance of the CBF at low arterial BPs is controversial: several papers reported a significant contribution (106–108, 113, 185, 225), whereas others failed to confirm these findings (26, 201, 249).

The importance of neuronal regulation in the cerebral circulation and specifically in the autoregulation was controversial and has been discussed extensively in the past (18, 202). However, it became evident recently that neuronal mechanisms contribute significantly to the regulation of CBF, and, beside neurons and perivascular nerves, astrocytes are also active participants in these neurovascular control functions. It has been established for many decades that cerebral blood vessels receive innervation partly via the peripheral nervous system (autonomic and sensory fibers, including sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, originating in the superior cervical, sphenopalatine, otic, and trigeminal ganglia) and partly within the CNS (from the locus coeruleus, basal nucleus of Meynert, dorsal raphe nuclei, and fastigial nucleus) (18, 62, 101, 199). However, the functional significance of this dense innervation was unclear for a long time, partly because of the marked diversity of experimental observations obtained in different species, under different types of anesthesia and in different brain regions (202). The variability of the responsiveness of the different sections of the cerebral vasculature further complicated the picture. For instance, it has been shown that, under resting conditions, sympathetic stimulation constricts large cerebral arteries, whereas small vessels dilate, and the overall cerebrovascular resistance remains unchanged (13, 62). During acute hypertension, however, sympathetic nerves constrict both large and small arteries, and the consequent increase in cerebrovascular resistance significantly contributes to the autoregulation of the CBF and the prevention of BBB disruption (13, 92).

EFFECTS OF ARTERIAL BLOOD-GAS TENSIONS ON THE CBF.

It is known that CBF is increased by hypoxia, hypercapnia, and even more by concomitant hypoxia and hypercapnia (H/H) (39, 111, 208). The obvious importance of this regulation is to prevent insufficient oxygen supply to the brain tissue when the arterial blood, for any reason, is not sufficiently saturated with oxygen. Hypoxic and hypercapnic stimuli can act on cerebral blood vessels by releasing various local mediators. Both endothelial and neural mechanisms are involved in the CBF regulation related to changes in arterial blood-gas tensions (204). H/H may be accompanied by extra- and/or intracellular acidosis, leading to relaxation of the cerebrovascular smooth muscle (205). It was shown in intraparenchymal cerebral arterioles that, at normal pH, CO2 fails to produce any significant vasodilation, indicating that it is the change in extracellular proton levels and not the CO2 concentration that is responsible for the alteration of the vascular tone (157). The fast changes in pH that occur during hypercapnia were shown to modulate NO production, and it has been proposed that the extracellular pH may be the main trigger of hypercapnia-induced, NO-dependent relaxation of the cerebral arteries (204, 205).

Regulatory pathways activated by changes of neuronal activity.

Coupling of local CBF to increased neuronal activity, i.e., the “functional” or “active” hyperemia of the brain, is an essential component of cerebrovascular regulation. The exact localization of vasodilation to the active brain regions is facilitated by the proximity of sites of neuronal electrical activity and neurotransmitter release to the cerebral vasculature (127). The close spatial relationship between hyperemia and neuronal activity is the basis of most of the current functional brain imaging techniques (210). Neurotransmitters released during synaptic transmission, vasoactive products of cellular metabolism, and ionic signals are thought to play a major role in this regulatory function. Based on recent experimental observations, the present view of the neurovascular coupling implies that 1) neuronal mechanisms are responsible for the rapid, dynamic adjustment of regional CBF (rCBF) to the local metabolic demands of the brain; and 2) once the blood flow is adjusted to the metabolic needs, further maintenance of the flow/metabolism balance is ensured by vasoactive metabolites and mediators (202).

The original concept of flow-metabolism coupling in the brain, as described by Roy and Sherrington (198), presumed a negative feed-back control system in which the increased neuronal activity and consequent increase of metabolism results in locally reduced O2 and increased CO2 tensions, leading in turn to the accumulation of vasodilator compounds (adenosine, H+, lactate, K+), which reset the balance between metabolic demand and energy supply via increasing CBF. Metabolic regulators of CBF that participate in flow-metabolism coupling include substances released by neurons into the perivascular space during periods of increased metabolic demand, as a result of immediate changes in tissue energy balance following neuronal activity and synaptic transmission (243). An example is the ATP-derived neurotransmitter and vasodilator adenosine, which may be released by neurons during metabolic deprivation induced by neuronal firing (49, 182). Adenosine contributes to matching CBF to metabolic demand in conditions such as neuronal activity, hypoxia, and hypercapnia, with a major role attributed to the adenosine receptor A2A (99, 151). The primary effect of receptor signaling is the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels with consequent smooth muscle relaxation and elevated CBF (182).

Local cerebral hyperemia induced by neuronal activation, however, cannot be explained solely by the activity-induced accumulation of metabolic end-products. The reason for that is threefold. Observations indicate that 1) rCBF may increase without significant changes in local cerebral metabolism; 2) the increase in rCBF may be out of proportion compared with the local metabolic demands; and 3) most importantly, the increase in rCBF may precede the accumulation of the vasodilator metabolic end-products (202). Recent data obtained by functional neuroimaging indicate the major importance of neuronal mechanisms in coupling rCBF to the metabolic needs of the brain. For instance, it was demonstrated that, during neuronal activation, the increase in rCBF occurs earlier than the reduction of tissue O2 tension and the increase of CO2 tension. These observations support the view that a feed-forward type control based on the close cooperation between elements of the neurovascular unit (neurons, astrocytes, microvessels) is responsible for the efficiency of neurovascular coupling (54, 70, 98, 114). According to this concept, increased synaptic activity and neurotransmitter release initiate the regulatory process. In the case of glutamatergic transmission, this would activate the N-methyl-d-aspartate and metabotropic glutamate receptors of the postsynaptic neurons, as well as those of the neighboring astrocytes. As a consequence, AA metabolites NO and K+ will be released from these cells, leading to dilation of the cerebral vessels (69, 96, 229).

Astrocytes were recently reported to play a major role in neurovascular coupling (70, 98, 255). When arteries enter the cortical parenchyma beyond the Virchow-Robin space, extrinsic innervation is lost, and the vessels become surrounded by astrocytic endfeet (55). It is known that astrocytes send processes to synapses, the sites of the most energy-consuming neuronal function, they cover arterioles with their endfeet, and communicate with other astrocytes through gap junctions and via the paracrine release of ATP (114). These unique morphological properties make astrocytes ideal messenger cells to carry signals of neuronal activation to blood vessels. Information from active neurons is integrated by astrocytes, which generate increases in endfoot Ca2+ concentration as a result of neurotransmitter receptor activation and subsequent inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production (69). This Ca2+ signal in the endfoot may activate neuronal NO synthase (NOS; nNOS), as well as Ca2+-sensitive phospholipase A2, thereby releasing AA, which dilates cerebral arterioles and microvessels through the production of vasodilator prostanoids and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (96, 101, 129, 130, 209). At the same time, nNOS-derived NO dilates cerebral vessels via activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase in the vascular smooth muscle (70, 98).

Pericytes, a unique cell type of the cerebral vasculature with both smooth muscle and macrophage properties, have also been implicated recently as important components of the neurovascular unit (68, 72). These cells were shown to control capillary diameter by constricting the vascular wall, and this effect may significantly influence capillary blood flow during reperfusion after cerebral ischemia (176, 258). Pericytes express receptors for vasoconstrictor substances such as angiotensin II, endothelin-1 (ET-1), and vasopressin, which mediate reduction of capillary diameter and blood flow (200). In contrast, NO causes the relaxation of pericytes through cyclic guanosine monophosphate production (85). Furthermore, prostacyclin and adenosine were also shown to relax pericytes (200), and the consequent decrease in cerebrovascular resistance may significantly contribute to neurovascular coupling (67). In fact, pericytes may play a major role in the very fine spatial distribution of blood flow to small groups of active neurons by increasing the diameter of nearby capillaries (200).

Similar to pericytes, two specialized subsets of the monocyte/macrophage-related microglia can also be found in the ultimate vicinity of the cerebral microvessel's basal membrane and, therefore, could potentially be involved in vasoregulation: the perivascular microglia enclosed within the basal lamina, and the juxtavascular microglia, which is attached to the abluminal side of the membrane (79). Although these cells have not yet been shown to influence capillary or arteriolar diameter directly, they are able to release vasoactive substances (prostanoids, NO, reactive oxygen species, and ATP), which may alter the tone of smooth muscle cells and pericytes, especially under pathophysiological conditions.

Biosynthesis and Receptors of Endocannabinoids in Cells Involved in Cerebrovascular Regulation

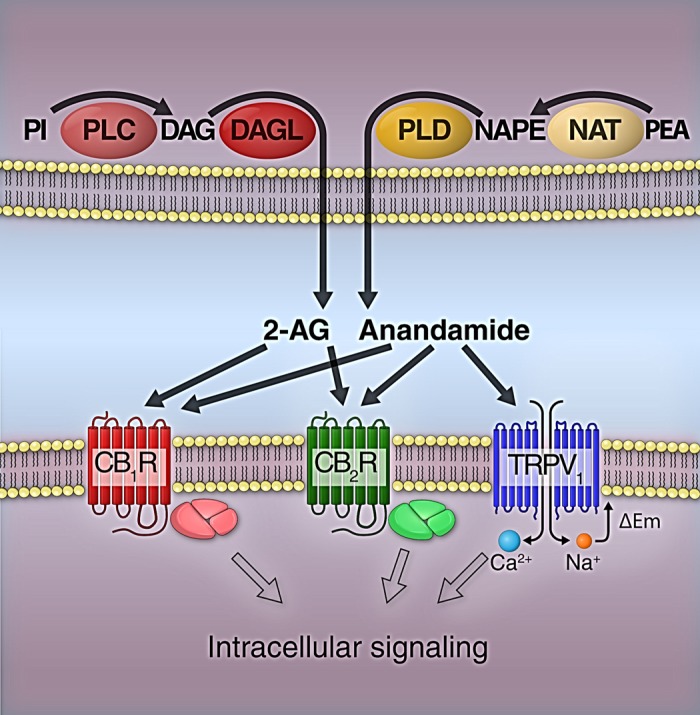

Endocannabinoids are endogenous analogs of the psychoactive constituents of cannabis plants. The first endocannabinoid, N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA, anandamide), was discovered by Devane and colleagues in 1992 (46). As lipid-soluble molecules, they are released immediately after their synthesis from the phospholipids of cell membranes. The main synthetic pathways of the principal endocannabinoids, AEA and 2-arachydonylglycerol (2-AG), are illustrated in Fig. 2, but a variety of alternative pathways have also been described in different species and cell types (21). The biological actions of endocannabinoids are terminated by protein-mediated cellular uptake and subsequent metabolism by different enzymes, including fatty acid amide hydrolases, monoacylglycerol lipase, N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase, cyclooxygenase-2, and different lipoxygenase isozymes (11). Interestingly, these enzymatic conversions may give rise to other biologically active lipid mediators, such as AA, oxidized endocannabinoids, and prostaglandin-ethanolamides and -glyceryl esters (231).

Fig. 2.

Main biosynthetic pathways and targets of 2-arachydonylglycerol (2-AG) and anandamide. Phospholipase C (PLC) converts phosphatidylinositol (PI) to diacylglycerol (DAG), which is further converted to 2-AG by DAG lipase (DAGL). Anandamide is synthesized by phospholipase D (PLD) from N-arachidonoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE), which is produced from phosphatidylethanolamine (PEA) by N-acyltransferase (NAT). 2-AG and anandamide can activate both cannabinoid 1 (CB1R) and cannabinoid 2 receptors (CB2R). In addition, anandamide was reported to interact with the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) ion channel. Activation of CB1R and CB2R induces cellular actions via heterotrimeric G protein-mediated pathways, whereas the intracellular signaling of TRPV1 channels is initiated by Ca2+ influx and cell membrane depolarization (ΔEm).

Endocannabinoids exert their biological actions mainly through binding to cell membrane receptors and ion channels (Fig. 2). It was first described by Devane et al. (45) in 1988 that rat brain membrane preparations have high-affinity binding sites for cannabinoids. This receptor was later cloned from rat brain cDNA library and named cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptor (141). The CB1 receptor has been found all around the CNS, as well as in the periphery, in both neural and nonneural cells. The CB1 receptor belongs to the superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that can activate multiple cell signaling pathways by activating different G proteins (Fig. 2). Coupling of CB1 receptors to Gi/o protein results in the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and activation of G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels. CB1 receptor stimulation reportedly initiates Ca2+ signaling, although it is not clear whether it is mediated by Gβγ-subunits of Gi/o protein or by Gq. Cellular responses associated with CB1 receptor activation may also involve altered conduction of voltage-gated calcium channels (for review, see Ref. 230).

Three years after the cloning of the CB1 receptor, in 1993 a new cannabinoid receptor was identified in a human leukemic cell line and named CB2 receptor (155). The CB2 receptor is also a member of GPCRs (Fig. 2) and can couple to pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o proteins, but, unlike the CB1 receptor, it cannot couple to other G proteins (for review, see Refs. 165, 174). Since its original identification in immune cells, the CB2 receptor was found in many different tissues, including the CNS, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems. In the immune system, the CB2 receptor is expressed by all leukocyte types, and its activation leads to immunosuppression. In other organ systems, the CB2 receptor has rather been implicated in pathophysiological roles, as its expression is upregulated by injury and in certain diseases (174).

In addition to CB1 and CB2 receptors, endocannabinoids can also affect other molecular targets, often called “non-CB1/non-CB2 receptors” (16, 179). Perhaps the most extensively studied of these is the transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 (TRPV1) receptor, which is a nonselective cation channel from the six-transmembrane-domain transient receptor potential family (Fig. 2). In addition, the orphan GPCR, GPR55, was proposed as one of the missing putative cannabinoid receptor subtypes (7), although recent data suggest that its main endogenous ligand is lysophosphatidylinositol (94). GPR55 signalization appears primarily coupled to Gα13 and RhoA activation (94). The mRNA transcripts of this receptor have been found both in the CNS (dorsal striatum, caudate nucleus, and putamen) and peripheral organs (ileum, testis, spleen, tonsil, breast, some endothelial cell lines), but the expression of the GPR55 protein in these tissues still needs to be established (for review, see Refs. 94, 80). GPR55 mRNA was found in mouse primary microglia cells and in murine microglial cell line (183), as well as in human brain endothelial cells (91), indicating that this receptor may also be involved in the regulation of CBF by endocannabinoids or other lipid mediators.

In 1999, Járai and coworkers (105) reported that abnormal cannabidiol (abn-cbd) elicits hypotension and endothelium-dependent mesenteric vasodilation in mice lacking both CB1 and CB2 receptors, yet the CB1-antagonist SR141716A blocked these effects. This observation indicated the existence of an endothelial non-CB1/non-CB2 receptor, which is now referred to as abn-cbd receptor, or endothelial anandamide receptor. The presence of such receptors was also confirmed in rabbit aortic ring preparations and rat aortic endothelial cells (143, 154), as well as in rabbit pulmonary arterial strips (221). In the CNS, microglial abn-cbd receptors mediate neuroprotective effects (119) and regulate cell migration (247). The molecular identity of this endothelial cannabinoid receptor is still controversial. Until now, two orphan GPCRs have been suggested to be identical with it: one is GPR55, which shares several key features with the abn-cbd receptor (80), but, more recently, McHugh and colleagues (144, 145) suspected GPR18 to be the putative abn-cbd receptor.

Release of endocannabinoids from cells within and around the cerebral vasculature.

Endocannabinoids can be released and metabolized by a number of cell types involved in cerebrovascular regulation. Di Marzo and colleagues (48) demonstrated first that AEA is produced by cultured neurons when stimulated with membrane-depolarizing agents. Three years later, the same group, as well as Stella et al. (220), found that 2-AG is also released from neurons in a Ca2+-dependent manner and can reach concentrations 170 times higher than those of AEA in the brain (20). In addition, astrocytes were also shown to produce 2-AG (220), AEA, and other acylethanolamides (246). Production of endocannabinoids in astrocytes is Ca2+ dependent and can be upregulated by ET-1 (246, 248) and ATP (245). Microglia also responds to ATP with endocannabinoid production, although P2X7 receptors, which mediate this effect, are only expressed in activated cells (252). Microglial cells were shown to produce ∼20-fold more endocannabinoids than neurons or astrocytes in culture (246, 247). More recent studies also emphasize that tissue injury promotes the production and release of endocannabinoids and related eicosanoids (9, 30, 159).

Besides neurons, astrocytes and microglia, cells of the cerebral vasculature itself, are also potential sources of endocannabinoids. Randall and coworkers (191, 193) identified AEA as a possible endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor in the mesenteric vascular bed as well as in the coronary artery. Later, the endothelial production of 2-AG was also confirmed, both in isolated rat aorta (146) and in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (222). The cerebrovascular endothelium was also shown to release AEA after stimulation with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 (35). Blood-derived cells, either in the lumen of the vessels or after extravasation, can also produce endocannabinoids in the systemic and cerebral circulation. Both 2-AG and AEA are released by platelets and activated macrophages and implicated as paracrine mediators under certain pathophysiological conditions, like LPS-induced hypotension (235), myocardial infarction (240), liver cirrhosis (8), and hemorrhagic shock (242). LPS increase endocannabinoid levels not only in activated macrophages, but also in human lymphocytes, by inhibiting the cannabinoid-degrading enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase at the gene transcriptional level (136).

Recently, 2-AG release by the vascular smooth muscle has been demonstrated as a consequence of the activation of certain seven-transmembrane domain receptors associated with heterotrimeric Gq/11 proteins (223, 224). In the process of intracellular signaling the Gαq/11 subunit mediates activation of phospholipase Cβ, which catalyzes the conversion of the cell membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol (DAG). As shown in Fig. 2, DAG can be further converted by DAG lipase to 2-AG, which can be released by the vascular smooth muscle cells and act as a paracrine mediator, reducing the tension of the vascular smooth muscle. This mechanism has been proposed as a negative feed-back control system for attenuating the vasoconstriction mediated by AT1 angiotensin receptors and α1-adrenoreceptors (223, 224).

Presence of cannabinoid receptors and TRPV1 channels in cells involved in cerebrovascular regulation.

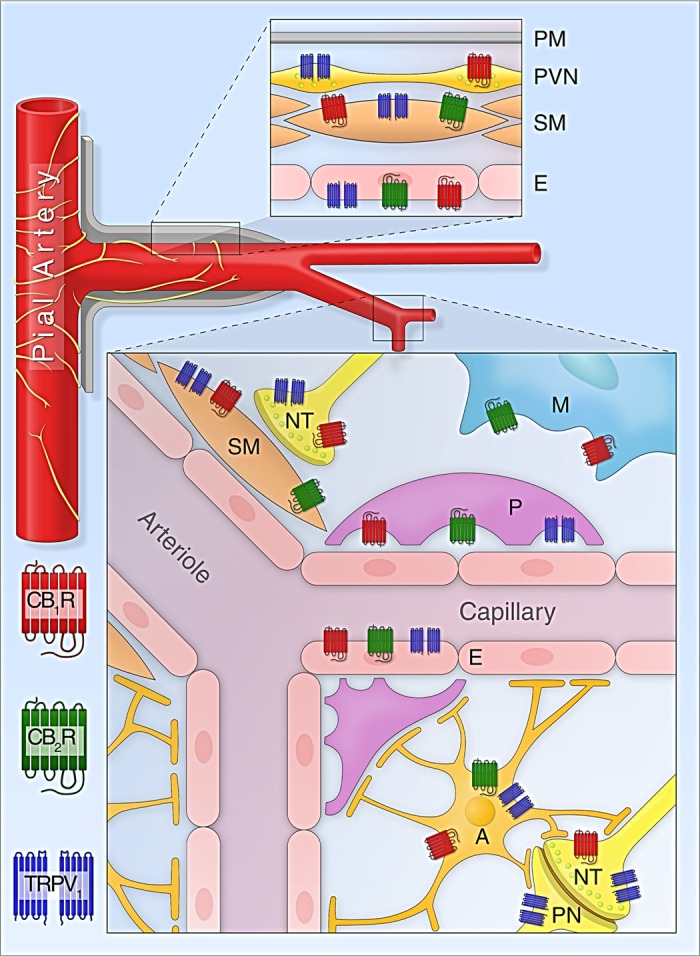

CB1 receptors are primarily expressed on neurons, mainly on axons and synaptic terminals (Fig. 3), indicating the importance of this receptor in modulating neurotransmission (137). In the CNS, the expression of CB1 receptors was also demonstrated in astrocytes, microglial cells, pial vessels, cerebral microvascular smooth muscle cells, human brain endothelium, and pericytes (37, 78, 81, 131, 222, 259) (Fig. 3). Activation of CB1 receptors in cat cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells decreases the opening of L-type calcium channels (78), whereas in endothelial cells it stimulates Ca2+ influx (81), as well as activates the MAP kinase cascade (128, 189). Ashton et al. (5) reported CB1 receptor immunoreactivity in rat cerebral arteries with diameters from 40 to 300 μm, but not in veins, with dominant expression in the smooth muscle.

Fig. 3.

Expression of cannabinoid receptors and TRPV1 channels in cells involved in cerebrovascular regulation. Top inset: cannabinoid receptors and TRPV1 channels in the wall of pial and penetrating arteries (E, endothelium; PM, pia mater; PVN, perivascular nerve; SM, smooth muscle). Bottom inset: expression of cannabinoid receptors and TRPV1 channels in the neurovascular unit and related cells of the cerebral microcirculation (A, astrocyte; M, microglia; NT, nerve terminal; P, pericyte; PN, postsynaptic neuron).

The expression of cannabinoid receptors on microglial cells and astrocytes was recently reviewed (219). In some species, the CB1 receptor is expressed by microglial cells in culture. However, since cultured microglia is intrinsically activated by the transferring procedure, it is likely that resting microglia in intact healthy brain tissue expresses less or no CB1 receptor. Cultured rat astrocytes also express CB1 receptor, and its activation controls their metabolic functions, as well as their ability to produce vasodilator and inflammatory mediators, such as NO. In adult rat brain, most of the perivascular astrocytes express CB1 receptor, which presumably regulates energy supply to neurons by increasing the rate of glucose oxidation and ketogenesis (219).

Several cell types of the neurovascular unit have been reported to express CB2 receptors (Fig. 3). With regard to neurons, Van Sickle and colleagues (232) identified CB2 in the cortex and cerebellum, and also in neurons from the brain stem, where it exerts an anti-emetic effect, which is still a very controversial issue (52, 165). It is not surprising that activated microglia expresses CB2 receptors, and their activation mediates immune-related functions, as reviewed by Stella (219). Microglia cultures of human, rat, and mouse origin express significant amounts of CB2 receptors. According to the findings of Núñez et al. (160), in the human cerebellum only specific subpopulations of microglial cells express CB2 receptors: while parenchymal microglia lacks any significant CB2 staining, perivascular microglial cells show exceedingly high levels of CB2 expression around almost every blood vessel, indicating a potential role of CB2 in the regulation of CBF and/or in maintenance of the BBB. However, in other studies, CB2 receptor-positive microglia was found to be more widespread in the cerebellum (6). Activated microglial cells from mice exhibit the highest CB2 receptor density on the leading edges (the front of migrating polarized cells), which may mediate their migration toward the source of endocannabinoid release, i.e., damaged neurons (247). Cerebrovascular endothelial cells express CB2 receptors together with CB1 and TRPV1 receptors, and these receptors are functional and possibly cooperative (81, 131). Zhang et al. (259) reported CB2 receptor expression in endothelial and smooth muscle cells of cerebral blood vessels, pericytes, astrocytes, and microglia. A recent study found that CB2 is expressed on vascular, but not on astroglial, cells in the postmortem human Huntington's disease brain (52). Furthermore, selective activation of CB2 receptor in endothelium and/or leukocytes suppresses their interaction and protects the BBB (177, 195). Similarly, CB2 activation also attenuates the proinflammatory response in human coronary and hepatic endothelial cells (9, 97, 188).

The TRPV1 channel, which was identified originally in sensory neurons colocalized with CB1 receptors, is widely expressed in neuronal and nonneuronal cells of the brain (Fig. 3). TRPV1 channels were demonstrated in neurons of the hippocampus, basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebral peduncle, pontine nuclei, periaqueductal gray matter, cerebellar cortex, and dentate nucleus (41). TRPV1 is expressed both presynaptically, where it is involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release, and postsynaptically, where it influences neurotransmitter signaling (47). Beside neurons, TRPV1 channels are also expressed by astrocytes, pericytes, as well as by cerebrovascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells (32, 81, 227). Activation of TRPV1 is known to control vascular responses: in endothelial cells and sensory nerves it causes the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide CGRP, a potent vasodilator (132, 260), whereas in smooth muscle cells TRPV1 activation is coupled to vasoconstriction in various arterial beds (32, 42, 109), including isolated middle cerebral arteries and pial arterioles (56).

The widespread distribution of the CB1, CB2, and TRPV1 receptors in cells involved in cerebrovascular regulation (Fig. 3) raise the possibility of multiple mechanisms of cannabinoid actions on the cerebral circulation. Endocannabinoids can directly influence cerebrovascular resistance and, consequently, the blood perfusion of the brain by modulating the contraction and relaxation of the smooth muscle cells of pial, large penetrating and smaller intraparenchymal arteries, arterioles and precapillary sphincters, as well as the tone of pericytes via the cannabinoid receptors expressed by these cells. The endothelium plays a pivotal role in the regulation of the cerebral circulation by releasing vasoactive mediators upon chemical and biomechanical stimuli, which regulatory pathways can also be influenced by the activation of endothelial cannabinoid receptors. In addition, cells involved in the neuronal control of the cerebral circulation, such as perivascular nerves of pial and penetrating arteries, as well as intrinsic neurons sending axons to intraparenchymal vessels, also express functional cannabinoid receptors, both on their cell bodies and on the varicosities of nerve fibers, as well as on axon terminals. Furthermore, synaptic transmission, the most energy-consuming neuronal function and, therefore, the strongest signal for inducing functional hyperemia in the brain, is also under the control of endocannabinoids, which in this way can also influence neurovascular responses by changing the metabolic demand of neurons. Finally, the expression of cannabinoid receptors by microglial cells and leukocytes may have a relevance in cerebrovascular regulation under pathophysiological conditions, when the release of vasoactive cytokines from these cells is controlled by endocannabinoids.

Cerebrovascular Actions of Exogenous and Endogenous Cannabinoids

The effects of cannabinoids on cardiovascular functions have been studied extensively since the discovery of phytocannabinoids in the 1960s and the identification of endocannabinoids in the early 1990s (121, 150, 167, 192). Numerous observations indicate that endocannabinoids participate in the control of systemic arterial BP and cardiac output and play a role in the regulation of regional vascular resistance and, consequently, in the blood supply to different organs, including the brain (12, 166, 213). Bátkai et al. (10) showed that endocannabinoids tonically suppress cardiac contractility in adult, hypertensive rats, and BP can be normalized by enhancing the CB1-mediated effects of endogenous AEA by blocking its hydrolysis. In anesthetized rats and mice, intravenous injection of AEA resulted in triphasic changes of systemic arterial pressure and heart rate (163). In the first, vagally mediated phase, a precipitous fall in the heart rate and BP can be observed for a few seconds. In the second phase, a brief pressor response develops. Since the elevated BP cannot be reduced either by using α-adrenergic blockade or by abolishing sympathetic tone by pithing, it is not sympathetically mediated (234). The transient but significant pressure increase remains unaffected after pharmacological CB1 receptor blockade and also persists in CB1-knockout (KO) mice, indicating that CB1 receptors are also not involved in the hypertensive response. The third phase of the pressure changes following AEA administration is characterized by hypotension and moderate bradycardia. This cannot be observed in conscious, normotensive rats (125, 217), but it is present and longer lasting in conscious, spontaneously hypertensive rats (10, 126). Considering that sympathetic tone is low in undisturbed conscious, normotensive rats compared with hypertensive animals (31), these results support the view that bradycardia and hypotension, induced by AEA administration, is a consequence of sympathoinhibition.

Data on the cerebrovascular effects of cannabinoids are limited and partly contradictory in the literature (Table 1). In a human study, marijuana smoking resulted in increased CBF and elevated Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) level in the plasma (139). Δ9-THC was shown to increase blood perfusion of the brain in both dogs and humans (15, 138, 140). In anesthetized rats, administration of AEA as well as of the CB1 receptor agonist HU-210 resulted in an increased CBF, which could be prevented by SR141716A, a CB1 antagonist (241). In conscious rats, however, CBF reduction was observed following intravenous administration of Δ9-THC or AEA (22, 218). These discrepancies can be attributed either to the large variety of target cells and mechanisms, by which cannabinoids may act on the cerebral circulatory system (194), or to differences in experimental conditions. It is noteworthy that decreased CBF upon cannabinoid administration was observed only in restrained conscious rats, whereas all other studies reported cerebral vasodilation and/or increased CBF. It has been shown that the baseline regional cerebral metabolic rate and its changes during N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor blockade show major differences in restrained conscious vs. anesthetized rats, which can be attributed to differences in the synaptic activity (122). Therefore, a possible explanation of the aforementioned controversies is that cannabinoids have a direct vasodilator action on cerebral vessels (as discussed below), but can decrease CBF indirectly by suppressing synaptic activity and, consequently, cerebral metabolic demand.

Table 1.

Cerebrovascular actions of cannabinoids

| Cannabinoid | Species | Method | Effect | Ref. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marijuana smoking | Human (in vivo, conscious) | 133Xe inhalation technique | Increased CBF (most pronounced in the frontal lobe, greater changes in the right hemisphere) | 139 |

| Δ9-THC | Human (in vivo, conscious) | Positron emission tomography | Increased CBF (most pronounced in the frontal lobe, insular and anterior cingulate regions, greater changes in the right hemisphere) | 138, 140 |

| Δ9-THC | Dog (in vivo, anesthetized) | Venous outflow | Increased intracranial blood flow | 15 |

| Anandamide | Cat (ex vivo) | Myography | Concentration-dependent vasorelaxation of pial arteries | 78 |

| Δ9-THC, anandamide | Rabbit (in vivo, anesthetized) | Closed cranial window | Dose-dependent vasodilation of cerebral arterioles | 58 |

| Anandamide | Rabbit (in vivo, anesthetized) | Angiography | Attenuated endothelin-1 induced vasospasm of the basilar artery | 50 |

| Anandamide | Guinea pig (ex vivo) | Myography | Vasorelaxation of the basilar artery | 260 |

| Anandamide, HU-210 | Rat (in vivo, anesthetized) | Radioactive microspheres | Lowered vascular resistance in the brain, increased CBF | 241 |

| Δ9-THC | Rat (in vivo, conscious) | Iodo-[14C]antipyrine autoradiography | Decreased CBF (in 16 of 37 areas measured, e.g., CA1 region of the hippocampus, frontal and medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, claustrum; other regions unaffected) | 22 |

| Anandamide | Rat (in vivo, conscious) | Iodo-[14C]antipyrine autoradiography | Dose and time dependent decrease in CBF (in 23 of 59 regions, e.g., amygdala, hippocampus, several cortical areas; other regions unaffected) | 218 |

Δ9-THC, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol; CBF, cerebral blood flow.

Among the possible cannabinoid targets in the cerebral circulation, the vasculature itself is an obvious one, which responds to CB1 administration by vasodilation, in a dose-dependent manner (58, 78, 241). Endocannabinoids can activate CB1 cannabinoid receptors located on both smooth muscle and endothelial cells of cerebral vessels (37, 78, 81). AEA and 2-AG were shown to induce Ca2+ influx and phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein in human brain capillary and microvascular endothelial cells (37, 81). AEA induced a concentration-dependent release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in human umbilical vein-derived EA.hy926 cells, without inducing capacitative Ca2+ entry, in contrast to the effects of histamine or the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (149). An important action of AEA is that, by activating CB1 receptors, it increases the activity of the constitutive endothelial and nNOS enzymes (71, 215). AEA is able to mobilize cytosolic Ca2+ from intracellular stores, but its ability is impaired by caffeine. The effect of the CB1-receptor antagonist SR141716A on cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization, however, is controversial (149). In cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells, isolated from cats, AEA, as well as the CB1 receptor agonist WIN-55212-2, induced inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels in a dose-dependent manner. Pretreatment with pertussis toxin or application of CB1 antagonist SR141716A abolished these effects (78). Concentration-dependent relaxation of preconstricted cerebral arterial segments was observed following either WIN-55212-2 or AEA administration, and the relaxation was sensitive to the CB1 antagonist SR141716A.

Taking together these observations, it is likely that, by modulating the influx of Ca2+ through L-type Ca2+ channels of the cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells, the CB1 receptor and its endogenous ligand(s) play a pivotal role in the regulation of the cerebrovascular muscle tone (78). Furthermore, cannabinoid receptors are also expressed by the cerebrovascular endothelium, although their contribution to endothelium-dependent vasodilation is ambiguous.

The cerebral circulation is tightly regulated by neuronal mechanisms (86, 199, 202), in which endocannabinoids may act as modulators of synaptic transmission (Fig. 3) and, thereby, influence the activity of neuronal pathways. In addition, CB1 receptors on peripheral sympathetic fibers were shown to inhibit norepinephrine (NE) release from nerve terminals (103), representing an additional potential mechanism for influencing cerebral circulation. Indeed, mRNA for the CB1 receptor is detected in the superior cervical ganglion of the rat (103), and WIN-55212-2 decreased the spillover of NE into the plasma in pithed rabbits with continuously stimulated sympathetic neuronal activity (158). In the guinea pig basilar artery, AEA induced vasorelaxation via activation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerves (104, 260, 261). Moreover, the vasodilatory responses of isolated arteries exposed to AEA were shown to be mediated through the TRPV1 receptor and to involve the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from perivascular sensory nerves (81, 104, 260).

Beside neurons and perivascular nerves, cannabinoids were also shown to activate CB1 receptors located on astrocytes, which play active roles in regulating CBF (211). Cannabinoid receptors may be linked to astrocyte signaling, namely to the release of AA, a substrate for various eicosanoids with cerebrovascular activity. Astrocytes are capable of metabolizing exogenous AA via COX, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase pathways (211). Furthermore, prostaglandins, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, AA, and K+ ions, all of which may be released by astrocytes, are candidate mediators of communication between astrocyte endfeet and vascular smooth muscle taking part in the neurovascular coupling (114).

Interactions between endocannabinoids and other vasoactive mediators, for instance ET-1 prostanoids, NO, and cytokines may explain certain observations on cannabinoid-related vascular effects. ET-1 is a strong vasoconstrictor, synthesized by the endothelium, following activation by a variety of physicochemical stimuli, including vasoactive mediators, such as arginine-vasopressin, angiotensin II, or thrombin (133). ET-1 acts on smooth muscle endothelin ETA receptors, thus activating phospholipase C, producing inositol trisphosphate, which causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels and vasoconstriction (83, 133), although an increasing body of evidence suggests the presence of an alternative signaling pathway involving G12/13-dependent activation of the Rho-Rho-kinase pathway (2, 251). 2-AG was shown to reduce ET-1-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in endothelial cells of human cerebral capillaries and microvessels, which was reversed partly by the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, SR141716, indicating a possible role of the CB1 receptor in the interaction of 2-AG with ET-1 (37). However, it was also observed that the signal transduction pathway for the 2-AG modulation of ET-1-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization was independent of NOS, COX, and lipoxygenase activity and was not mediated by cGMP- or cAMP-dependent kinases (37). The capacity of inhibitors of KCa channels to modulate 2-AG-induced reduction of ET-1-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization supports the potential interaction of 2-AG and ET-1 in the regulation of vasorelaxation induced by the yet unidentified endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor. These studies indicate the presence of a functional interaction between 2-AG and ET-1 and show the importance of an endogenous cannabinoid in balancing the effects of ET-1 in several pathological conditions, such as hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and hemorrhagic shock (37). In line with the above observations obtained in endothelial cell cultures, it has been shown in vivo that AEA significantly attenuates ET-1-induced vasoconstriction in rabbit basilar arteries (50).

AEA was also shown to interact with the prostanoid system, which plays a major role in the local regulation of cerebral circulation (17, 28, 123, 124). Experimental evidences suggest that cannabinoids are able to stimulate AA mobilization independently of the activation of CB1 or CB2 receptors (27, 65, 66). Also, AEA is degraded by the enzyme FAAH to ethanolamine and AA, and the latter stimulates prostaglandin formation and dilates cerebral arterioles (59). In addition, it was shown that AEA-induced vasodilation of rabbit cerebral arterioles was inhibited by indomethacin, a COX inhibitor, which indicates a COX-dependent mechanism in mediating the effect (58). It has been shown recently that repeated exposure to Δ9-THC results in synaptic and memory impairments, which are mediated by cerebral induction of COX-2 in a CB1-dependent manner. However, the potential consequences of this interaction on the cerebral circulation have not been addressed (36). Interestingly, several recent studies demonstrated that COX-2 can convert 2-AG to prostaglandin-glyceryl esters, whereas it can convert AEA to prostaglandin-ethanolamides (prostamides) (231). Among these endocannabinoid metabolites, prostaglandin F2α ethanolamide (prostamide F2α) is the most intensively studied species with marked effects on intraocular pressure, hair growth, fat deposition, and nociception (253).

Cannabinoids also interact with the NOS system, which plays important roles in the regulation of the cerebral circulation (62, 100, 118). Previous studies have shown that endocannabinoids may induce NO release via the constitutive endothelial and nNOS enzymes, by activating the CB1 receptor (71, 215). AEA also stimulates the activity and expression of the inducible NOS in endothelial cells (135). AEA-induced NO release was sensitive to the selective CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716A (rimonabant), suggesting the involvement of CB1 receptors in this signaling pathway (135). In endotoxin/cytokine-activated microglial cells, however, the synthetic cannabinoid (−)-CP-55940 was shown to inhibit inducible NOS-mediated NO production in a CB1-dependent manner (244). In addition, in vivo blocking the re-uptake of AEA with AM404 suppressed ex vivo NO production in sciatic nerve homogenates, indicating that ECs may negatively regulate NO release from nitroxidergic nerves (40). On the other hand, NO reportedly enhances the cellular uptake of 2-AG and AEA by potentiating the activity of the putative anandamide transporter (19, 135). Therefore, the NO system may be part of a physiological regulation of endocannabinoid uptake, possibly linked to the activation of the CB1 receptor (135). This may be a mechanism through which AEA and 2-AG can achieve the negative feed-back control of their CB1-mediated actions.

Numerous experimental observations have pointed out the importance of endocannabinoids in modulating the production and release of cytokines (112), which in turn have been implicated in certain cerebrovascular functions, including the regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone under pathophysiological conditions (63, 93, 156, 214, 256). For instance, both synthetic cannabinoids and endocannabinoids were shown to inhibit TNF-α release and mRNA expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated cultured microglial cells, although the receptor mediating the effect could not be exactly identified (61, 186), whereas in a subsequent study the CB2 receptor was shown to play a major role in suppressing TNF-α expression in LPS-stimulated primary microglia (196). Interestingly, CB2 activation also attenuates TNF-α-induced proinflammatory responses in human coronary endothelial cells (188). In cerebellar granule cells stimulated by LPS, the synthetic CB1/CB2 agonist CP-55940 dose-dependently inhibited IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA expression (38). However, the effects of CP-55940 could not be reproduced by endocannabinoids and were not sensitive to CB1/CB2 blockade, indicating a CB receptor-independent signaling pathway in mediating the response. Taken together, these data indicate that cannabinoids suppress the release of TNF-α and other cytokines during inflammation by diverse mechanisms involving CB2 and a putative non-CB1/non-CB2 cannabinoid receptor.

Finally, endocannabinoids may also have indirect effects on cerebral circulation by influencing respiration and subsequently the blood-gas levels, since high arterial CO2, as well as low O2 tensions, induce strong cerebral vasodilation, whereas hypocapnia reduces CBF. Both phytocannabinoids (33, 51, 60, 84, 152, 181, 197) and endocannabinoids (10, 117, 126, 168, 180, 206) were shown to suppress respiration, and several lines of evidence indicate that this effect is mediated by CB1 receptors. For instance, the CB1 antagonist AM-281 was reported to inhibit the respiratory effects of intravenous applied anandamide in rats (117). Furthermore, intravenous administration of the specific CB1-agonists WIN-55212-2 and CP-55940 induced a similar respiratory depression to that of Δ9-THC in rats, and the effect of WIN-55212-2 was sensitive to the CB1-antagonist SR141716A (206). WIN-55212-2 administered to the cisterna magna (180) or to the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata (168) also suppressed respiration in rats, and these effects could be blocked by CB1 antagonists, indicating that central CB1 receptors modulate negatively the respiratory control circuits. In rhesus monkeys, WIN-55212, AEA, as well as Δ9-THC, influenced respiratory functions and notably decreased tidal volume without affecting respiratory frequency. These effects could be reversed by SR141716A, indicating the involvement of CB1 receptors (238).

The experimental strategy in the aforementioned studies aiming to evaluate the role of endocannabinoids in cerebrovascular regulation was mostly to observe changes upon activation of cannabinoid receptors. One may suppose, however, that the effects of exogenously applied phyto- or endocannabinoids may be quite different from those induced by a complex endogenous control system. To overcome these limitations, in a recent study, the effects of suppressed endocannabinoid activity on the regulation of the cerebrocortical blood flow was investigated (102). AM-251, which is both antagonist and inverse agonist of the CB1-receptors (87, 178), failed to alter significantly either the systemic or the cerebral circulation. This indicates that, under resting physiological conditions, CB1 receptors have no constitutive influence on the cardiovascular system, and these data are in agreement with observations on the normal hemodynamic profile obtained in CB1-KO mice (153, 187).

The role of CB1 receptors in the CBF response evoked by combined H/H was also investigated in the same study, in which blockade of CB1 receptors significantly enhanced cerebrocortical hyperemia during H/H (102), indicating that endocannabinoids play an inhibitory role in the CBF response. Since neurons as well as astrocytes abundantly express CB1 receptors (74, 219), these observations can be explained by a CB1-mediated modulation of the nNOS activity. It was reported that, in cerebellar granule cells, CB1 agonists inhibit K+-induced NOS activation without influencing the basal rate of NO release, and the CB1-antagonist rimonabant was able both to reverse the effect of CB1 activation and to produce an increase in NOS activity that was additive to the effect of K+ ions (95). In addition, glutamatergic transmission (74) and metabolic activity of neurons and astrocytes (53) can be inhibited via the CB1 receptors. These effects may influence the release of NO and other vasoactive mediator substances, which subsequently alter CBF. It is well documented that hypoxia suppresses glutamate uptake by astrocytes, and, therefore, they can act as potential oxygen sensors in this control system (233). The increased glutamate levels during hypoxia may activate a glutamate receptor-mediated release of vasoactive substances from the neuronal elements of the neurovascular unit. Furthermore, several studies have shown that H/H-induced cerebrovascular responses are influenced by perivascular nerves of sympathetic origin (29, 44, 82, 90, 239), a neural pathway that may be modulated prejunctionally by CB1 receptors (168). In the synaptic vesicles of the sympathetic nerves NE, ATP and neuropeptide Y are costored and coreleased, and the release of these mediators is inhibited by prejunctional CB1 receptors (190, 194). The exact mechanism by which CB1 receptors modulate the H/H-induced rise of CBF is not completely understood. Nevertheless, the fact itself that CB1-receptor blockade results in an increased CBF response to H/H indicates a pivotal role of a CB1-receptor-mediated neuronal mechanism in the regulation of CBF during H/H.

With regard to the potential physiological role of CB1 receptor-mediated inhibition of H/H-induced cerebral hyperemia, it could function as a protective mechanism of the brain. It is well established that hypoxia and hypercapnia, especially if they are sustained, may result in the development of brain edema (1, 250). Although the pathomechanism of H/H-induced brain edema is complex (257), cerebral vasodilation and the consequent increase of the hydrostatic pressure in brain capillaries is likely to play a key role in it. Therefore, the CB1-receptor-mediated attenuation of H/H-induced cerebral vasodilation, together with the beneficial effects of endocannabinoids on the integrity of the BBB (237), may represent a protective mechanism against the development of brain edema during hypoxia and hypercapnia.

The regulatory role of endocannabinoids in the systemic and cerebral circulation and the consequences of activating this system were investigated in an alternative way in a recent study (102). AM-404, a putative cannabinoid re-uptake inhibitor, which reportedly increases the endogenous levels of anandamide in the brain (64) induced triphasic changes in both the systemic and the cerebral circulation.

The first phase was characterized by transient hypertension, resembling the cardiovascular effects of AEA obtained in anesthetized mice (162, 163). CB1 blockade, however, was unable to influence the hypertensive effect of AM-404 as well as that of AEA in a previous study (163), indicating that it is not due to CB1-receptor-mediated mechanisms. The hypertensive effect of endocannabinoids can be explained with the aid of two observations. It is well documented that 1) TRPV1 is activated by anandamide (226); and 2) AEA-induced increase of total peripheral resistance and elevation of the systemic arterial pressure are absent in TRPV1-receptor-deficient mice (162).

The second phase of changes after AM-404 administration was characterized by the depression of respiration and consequent changes in arterial blood-gas tensions and pH, resulting in increased CBF. AM-251-induced CB1 blockade suppressed the blood-gas and pH changes related to the respiratory depression but, surprisingly, did not influence the increase of CBF. The effect of AM-251 on the cerebral circulation during H/H, discussed above, helps to explain this apparent discrepancy: while AM-251 inhibited the respiratory effect of AM-404, at the same time it significantly enhanced the reactivity of CBF to H/H, and these two opposite effects neutralized each other.

The third phase of changes following AM-404 administration was characterized by sustained hypotension and concomitant decrease of the CBF. Considering the facts that AM-251 was able to influence the hypotension, but the reduction of CBF remained unchanged, these findings indicate that CB1-blockade impaired the autoregulation of cerebrocortical blood flow at its lower BP range. It is likely, therefore, that CB1-receptors are previously unknown, important modulators of cerebral autoregulation, ensuring constancy of CBF during arterial pressure fluctuations, at least during the activated state of the endocannabinoid system. Since a large body of experimental evidence indicates the participation of neural components in cerebrovascular adaptation to systemic BP changes (86, 108, 207), this would not be surprising, yet further studies are required to verify this concept.

Translational Perspectives

Endocannabinoids themselves, as well as pharmacological interventions on their receptors, have been shown to interfere with the development and progression of certain CNS disorders, such as subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (75, 76), traumatic brain injury (TBI) (147, 212), and ischemic stroke (164). On the other hand, cerebrovascular dysfunction is a common feature in these disorders, raising the possibility that the cerebrovascular actions of cannabinoids play a significant role in their pathogenesis or resolution. For instance, the development and rupture of cerebral aneurysms, as well as the early and delayed cerebrovascular consequences of SAH, have been attributed recently to inflammatory changes in the vessel wall, and cytokines appear to play a pivotal role in this process (34, 77, 115, 156, 214, 236). Cannabinoids were shown to inhibit the production of TNF-α and other cytokines in LPS-stimulated microglial and cerebellar granule cells (61, 186), and in one study CB2 receptors were implicated to mediate this effect (196). CB2 activation was also reported to attenuate TNF-α-induced proinflammatory responses in human coronary endothelial cells (9, 97, 188). A similar interaction between TNF-α and endocannabinoids or synthetic CB2 agonists could potentially attenuate delayed cerebrovascular constriction and consequent brain ischemia after SAH, since TNF-α has been reported recently to play a significant pathogenic role in this process by enhancing the myogenic tone in cerebral arteries, resulting in the development of vasospasm (256). In accordance with these observations and the putative role of cytokines in the development of cerebrovascular dysfunction, CB2 stimulation was recently shown to attenuate the early brain injury following SAH (75, 76).

Endocannabinoids or pharmacological stimulation of their receptors has been reported to play a beneficial role in secondary TBI (147, 212). Both CB1 and CB2 receptors are implicated in mediating these effects, although their relative contribution may strongly depend on both the type and the extent of the primary insult, as well as on the progression stage of the secondary damage. Vascular dysfunction plays a significant role in the worsening of TBI as opening of the BBB leads to neurotoxicity and edema formation, whereas increased cerebrovascular resistance results in brain ischemia (212). The roles of endocannabinoids and cannabinoid receptors in the disruption of the BBB have been reviewed recently (237). The sustained enhancement of the cerebrovascular tone, which may ultimately lead to the development of vasospasm, can be attenuated by endocannabinoids by at least two different mechanisms. First, endocannabinoids may induce CB1-receptor-mediated vasodilation in cerebral vessels (58, 78, 241). Taking into account the relative rapid and pronounced elevation of endocannabinoid levels in the brain after cerebral trauma (172) and ischemia (148), this mechanism may contribute to the early protection against neuronal death by maintaining the blood supply to the injured tissue. Indeed, in a cerebral ischemia-reperfusion model, the CBF in the ischemic penumbra was found to be significantly reduced in CB1-KO mice compared with wild-type controls, indicating a marked CB1-mediated vasodilation in the ischemic brain (173). In accordance with these findings, the recovery of neurological functions after closed head injury was delayed in CB1-KO mice, and the beneficial effect of 2-AG administration observed in wild-type animals was absent in CB1-KOs (172). A second phase of TBI involving inflammation both in the vessel wall and in brain parenchyma develops within hours after the primary insult and contributes significantly to posttraumatic neurological symptoms (93, 120). During this period, CB2 receptor activation was shown to inhibit vascular and neuronal inflammation and to improve the neurological outcome (3, 57). Similar to findings in SAH, inhibition of the release and intracellular signaling of cytokines appears to play a crucial role in the beneficial effects of cannabinoids in secondary TBI (4, 170, 171).

Considering the complexity of modulating the endocannabinoid system for therapeutic gain, one should also consider that the chronic effects of the activation of the endocannabinoid system in various pathologies may be completely different from the described acute vasoregulatory effects. For example, chronic activation of CB1 signaling promotes vascular inflammation and plaque vulnerability in atherosclerosis, while the endocannabinoid-CB2 receptor axis exhibits an anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective role (216). Furthermore, stimulation of CB1 receptors induces profound cardiovascular effects in both rodents and humans (134). In various chronic neurodegenerative diseases, the situation is even more complex, since cannabinoids may differentially modulate impaired neuronal and vasoregulatory functions, as well as inflammation in a context and disease stage-dependent manner.

Summary

The high oxygen and glucose demand of the brain, as well as the life-threatening consequences of insufficient energy supply to neurons, explain why cerebral circulation is the most precisely regulated division of the peripheral vascular system. Therefore, it is not surprising that almost all cell types that are present in the brain are involved in the regulation of CBF. Cerebrovascular resistance depends primarily on the diameter of cerebral arterioles and capillaries, which are controlled directly by the contraction and relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes, and indirectly by the release of vasoactive mediators from the endothelium, neurons and perivascular nerves, astrocytes, microglial cells, platelets, and leukocytes. Excitingly, almost all of these cell types have functional endocannabinoid system, which may differently modulate the regulation of cerebral circulation in a very complex and context-dependent manner.

Experimental data accumulated since the late 1990s indicate that the direct effect of cannabinoids on cerebral vessels is vasodilation mediated, at least in part, by CB1 receptors. Cannabinoid-induced cerebrovascular relaxation involves both a direct inhibition of the smooth muscle contractility and a release of vasodilator mediator(s) from the endothelium. However, under stress conditions (e.g., in conscious restrained animals or during hypoxia and hypercapnia), cannabinoid receptor activation was shown to induce reduction of the CBF. A likely explanation for these observations is that, during the activation of neuronal circuits, CB1 receptors mediate inhibition on the electrical and/or metabolic activity of neurons and, consequently, inhibit neuronal vasodilator regulatory pathways and/or the metabolic demand of neurons. Finally, in certain cerebrovascular pathologies (e.g., SAH, as well as traumatic and ischemic brain injury) activation of CB2 (and probably yet unidentified non-CB1/non-CB2) receptors appear to improve the blood perfusion of the brain and attenuate neurological symptoms. Since these effects were observed mostly in the subacute phase of these diseases (hours or days after the primary insult), when vascular inflammation is a major pathogenic factor of ischemic complications and neuronal damage, inhibition of cytokine release from microglial cells, leukocytes, or activated endothelium is the likely mechanism of beneficial cannabinoid actions.

Nevertheless, to precisely analyze the exact mechanisms of the multiple endocannabinoid actions in cerebrovascular regulation, more sophisticated experimental approaches (e.g., cell-type-specific and inducible genetic interventions, topical application of pharmacological tools, and functional brain imaging with high temporal and spatial resolution) will be essential, which may also help to clarify the exact role of endocannabinoids in cerebrovascular pathologies, like SAH, TBI, and ischemic stroke.

GRANTS

The authors' own work presented in the review has been supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA K-62375, K-101775, and K-112964) and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Z.B. and E.R. prepared figures; Z.B., E.R., M.L.-I., P.S., and P.P. drafted manuscript; Z.B., E.R., M.L.-I., P.S., and P.P. edited and revised manuscript; Z.B., E.R., P.S., and P.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the extraordinary contribution of Prof. Arisztid G. B. Kovách (1920-1996) to cerebrovascular research. The authors are grateful to Drs. Bernadett Faragó, Bernadett Balázs, and Erzsébet Fejes for critically reading and formatting the manuscript, as well as to András Kucsa for preparing the figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adeva MM, Souto G, Donapetry C, Portals M, Rodriguez A, Lamas D. Brain edema in diseases of different etiology. Neurochem Int 61: 166–174, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Althoff TF, Offermanns S. G-protein-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells–implications for vascular disease. J Mol Med 93: 973–981, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amenta PS, Jallo JI, Tuma RF, Elliott MB. A cannabinoid type 2 receptor agonist attenuates blood-brain barrier damage and neurodegeneration in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res 90: 2293–2305, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amenta PS, Jallo JI, Tuma RF, Hooper DC, Elliott MB. Cannabinoid receptor type-2 stimulation, blockade, and deletion alter the vascular inflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 11: 191, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashton JC, Appleton I, Darlington CL, Smith PF. Immunohistochemical localization of cerebrovascular cannabinoid CB1 receptor protein. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 44: 517–519, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashton JC, Friberg D, Darlington CL, Smith PF. Expression of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in the rat cerebellum: an immunohistochemical study. Neurosci Lett 396: 113–116, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker D, Pryce G, Davies WL, Hiley CR. In silico patent searching reveals a new cannabinoid receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27: 1–4, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batkai S, Jarai Z, Wagner JA, Goparaju SK, Varga K, Liu J, Wang L, Mirshahi F, Khanolkar AD, Makriyannis A, Urbaschek R, Garcia N Jr, Sanyal AJ, Kunos G. Endocannabinoids acting at vascular CB1 receptors mediate the vasodilated state in advanced liver cirrhosis. Nat Med 7: 827–832, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batkai S, Osei-Hyiaman D, Pan H, El-Assal O, Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Hong F, Harvey-White J, Jafri A, Hasko G, Huffman JW, Gao B, Kunos G, Pacher P. Cannabinoid-2 receptor mediates protection against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. FASEB J 21: 1788–1800, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batkai S, Pacher P, Osei-Hyiaman D, Radaeva S, Liu J, Harvey-White J, Offertaler L, Mackie K, Rudd MA, Bukoski RD, Kunos G. Endocannabinoids acting at cannabinoid-1 receptors regulate cardiovascular function in hypertension. Circulation 110: 1996–2002, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battista N, Di Tommaso M, Bari M, Maccarrone M. The endocannabinoid system: an overview. Front Behav Neurosci 6: 9, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battista N, Fezza F, Maccarrone M. Endocannabinoids and their involvement in the neurovascular system. Curr Neurovasc Res 1: 129–140, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumbach GL, Heistad DD. Effects of sympathetic stimulation and changes in arterial pressure on segmental resistance of cerebral vessels in rabbits and cats. Circ Res 52: 527–533, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayliss WM. On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. J Physiol 28: 220–231, 1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaconsfield P, Carpi A, Cartoni C, De Basso P, Rainsbury R. Effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on cerebral circulation and function. Lancet 2: 1146, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begg M, Pacher P, Batkai S, Osei-Hyiaman D, Offertaler L, Mo FM, Liu J, Kunos G. Evidence for novel cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Ther 106: 133–145, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benyo Z, Gorlach C, Wahl M. Involvement of thromboxane A2 in the mediation of the contractile effect induced by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis in isolated rat middle cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18: 616–618, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benyo Z, Wahl M. Opiate receptor-mediated mechanisms in the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 8: 326–357, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bisogno T, MacCarrone M, De Petrocellis L, Jarrahian A, Finazzi-Agro A, Hillard C, Di Marzo V. The uptake by cells of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous agonist of cannabinoid receptors. Eur J Biochem 268: 1982–1989, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisogno T, Sepe N, Melck D, Maurelli S, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Biosynthesis, release and degradation of the novel endogenous cannabimimetic metabolite 2-arachidonoylglycerol in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Biochem J 322: 671–677, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blankman JL, Cravatt BF. Chemical probes of endocannabinoid metabolism. Pharmacol Rev 65: 849–871, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloom AS, Tershner S, Fuller SA, Stein EA. Cannabinoid-induced alterations in regional cerebral blood flow in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 57: 625–631, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohlen HG, Harper SL. Evidence of myogenic vascular control in the rat cerebral cortex. Circ Res 55: 554–559, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryan RM Jr, Marrelli SP, Steenberg ML, Schildmeyer LA, Johnson TD. Effects of luminal shear stress on cerebral arteries and arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2011–H2022, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryan RM Jr, Steenberg ML, Marrelli SP. Role of endothelium in shear stress-induced constrictions in rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke 32: 1394–1400, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchanan JE, Phillis JW. The role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Brain Res 610: 248–255, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burstein S, Budrow J, Debatis M, Hunter SA, Subramanian A. Phospholipase participation in cannabinoid-induced release of free arachidonic acid. Biochem Pharmacol 48: 1253–1264, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busija DW, Bari F, Domoki F, Horiguchi T, Shimizu K. Mechanisms involved in the cerebrovascular dilator effects of cortical spreading depression. Prog Neurobiol 86: 379–395, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busija DW, Heistad DD. Effects of activation of sympathetic nerves on cerebral blood flow during hypercapnia in cats and rabbits. J Physiol 347: 35–45, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Z, Mulvihill MM, Mukhopadhyay P, Xu H, Erdelyi K, Hao E, Holovac E, Hasko G, Cravatt BF, Nomura DK, Pacher P. Monoacylglycerol lipase controls endocannabinoid and eicosanoid signaling and hepatic injury in mice. Gastroenterology 144: 808–817 e815, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carruba MO, Bondiolotti G, Picotti GB, Catteruccia N, Da Prada M. Effects of diethyl ether, halothane, ketamine and urethane on sympathetic activity in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 134: 15–24, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavanaugh DJ, Chesler AT, Jackson AC, Sigal YM, Yamanaka H, Grant R, O'Donnell D, Nicoll RA, Shah NM, Julius D, Basbaum AI. Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci 31: 5067–5077, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavero I, Kubena RK, Dziak J, Buckley JP, Jandhyala BS. Certain observations on interrelationships between respiratory and cardiovascular effects of (-)-9-trans-tetrahydrocannabinol. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 3: 483–492, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaichana KL, Pradilla G, Huang J, Tamargo RJ. Role of inflammation (leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions) in vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg 73: 22–41, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen P, Hu S, Harmon SD, Moore SA, Spector AA, Fang X. Metabolism of anandamide in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 73: 59–72, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, Zhang J, Fan N, Teng ZQ, Wu Y, Yang H, Tang YP, Sun H, Song Y, Chen C. Delta9-THC-caused synaptic and memory impairments are mediated through COX-2 signaling. Cell 155: 1154–1165, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, McCarron RM, Ohara Y, Bembry J, Azzam N, Lenz FA, Shohami E, Mechoulam R, Spatz M. Human brain capillary endothelium: 2-arachidonoglycerol (endocannabinoid) interacts with endothelin-1. Circ Res 87: 323–327, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiba T, Ueno S, Obara Y, Nakahata N. A synthetic cannabinoid, CP55940, inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine mRNA expression in a cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanism in rat cerebellar granule cells. J Pharm Pharmacol 63: 636–647, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen PJ, Alexander SC, Smith TC, Reivich M, Wollman H. Effects of hypoxia and normocarbia on cerebral blood flow and metabolism in conscious man. J Appl Physiol 23: 183–189, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa B, Siniscalco D, Trovato AE, Comelli F, Sotgiu ML, Colleoni M, Maione S, Rossi F, Giagnoni G. AM404, an inhibitor of anandamide uptake, prevents pain behaviour and modulates cytokine and apoptotic pathways in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol 148: 1022–1032, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cristino L, de Petrocellis L, Pryce G, Baker D, Guglielmotti V, Di Marzo V. Immunohistochemical localization of cannabinoid type 1 and vanilloid transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptors in the mouse brain. Neuroscience 139: 1405–1415, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czikora A, Lizanecz E, Bako P, Rutkai I, Ruzsnavszky F, Magyar J, Porszasz R, Kark T, Facsko A, Papp Z, Edes I, Toth A. Structure-activity relationships of vanilloid receptor agonists for arteriolar TRPV1. Br J Pharmacol 165: 1801–1812, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Pozzi AT, Pandey A, Medow MS, Messer ZR, Stewart JM. Blunted cerebral blood flow velocity in response to a nitric oxide donor in postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H397–H404, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deshmukh VD, Harper AM, Rowan JO, Jennett WB. Experimental studies on the influence of the sympathetic nervous system on cerebral blood-flow. Br J Surg 59: 897, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devane WA, Dysarz FA 3rd, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 34: 605–613, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, Pertwee RG, Stevenson LA, Griffin G, Gibson D, Mandelbaum A, Etinger A, Mechoulam R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258: 1946–1949, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]