Abstract

Introduction

In overcrowded emergency department (ED) care, short time to start effective antibiotic treatment has been evidenced to improve infection-related clinical outcomes. Our objective was to study factors associated with delays in initial ED care within an international prospective medical ED patient population presenting with acute infections.

Methods

We report data from an international prospective observational cohort study including patients with a main diagnosis of infection from three tertiary care hospitals in Switzerland, France and the United States (US). We studied predictors for delays in starting antibiotic treatment by using multivariate regression analyses.

Results

Overall, 544 medical ED patients with a main diagnosis of acute infection and antibiotic treatment were included, mainly pneumonia (n = 218; 40.1%), urinary tract (n = 141; 25.9%), and gastrointestinal infections (n = 58; 10.7%). The overall median time to start antibiotic therapy was 214 minutes (95% CI: 199, 228), with a median length of ED stay (ED LOS) of 322 minutes (95% CI: 308, 335). We found large variations of time to start antibiotic treatment depending on hospital centre and type of infection. The diagnosis of a gastrointestinal infection was the most significant predictor for delay in antibiotic treatment (+119 minutes compared to patients with pneumonia; 95% CI: 58, 181; p<0.001).

Conclusions

We found high variations in hospital ED performance in regard to start antibiotic treatment. The implementation of measures to reduce treatment times has the potential to improve patient care.

Introduction

Overcrowding of emergency departments (ED) has become a worldwide challenge [1]. International measures of ED crowding have demonstrated a steady increase of ED visits over the past few decades [2]. In the United States (US) e.g., there has been an enormous increase in ED visits, coinciding with a downsizing in the number of ED institutions and consecutively longer ED lengths of stay (LOS). This was called a major problem (“national epidemic”) by the Institute of Medicine in 2006 [3]. Previously descripted reasons for crowding ED are multifaceted, e.g. involving non-urgent visits, “frequent-flyer” patients, influenza season, inadequate staffing, inpatient boarding, and hospital bed shortages [4]. Over the past 20 years, patients arriving in the ED have faced increasingly long average wait times, resulting in extended ED visit lengths [5–7]. Most important, these increases have been most pronounced for patients with severe, acute, and critical illnesses such as myocardial infarction and severe infections [5, 6, 8]. Focusing on acute infections, ED crowding was described to be associated with delayed and non-receipt of antibiotics in patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia [9, 10].

Investigating specific components and process steps, recently, a French group found significant associations between age and triage priority and the ED LOS of patients discharged from the ED [11]. Further literature has investigated the human toll of ED crowding, demonstrating relationships between crowding and negative patient-relevant outcomes, including poorer care, adverse events, medication errors and lower satisfaction [12–15].

The main purpose of this study was to perform a prospective international analysis of factors being associated with delayed administration of antibiotic therapy and ED care in patients with an acute infection requiring appropriate (e.g. antibiotic) therapy.

Methods

Study design and setting

We prospectively performed an observational cohort study of unselected adult medical admissions through the ED of three tertiary care hospitals in Switzerland, France, and US between March and October 2013. The Swiss hospital (Kantonsspital Aarau) is a 600-bed tertiary care hospital with most medical admissions entering the hospital over the ED. The French hospital (Hopital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris) is a large inner-city 1800-bed referral academic centre. The US hospital (Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, Florida) is a 687-bed community referral centre. As an observational quality control study, the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the three hospitals approved the study and waived the need for individual informed consent (main Swiss IRB: Ethikkommission Kanton Aargau (EK 2012/059); French IRB: CCTIRS—Le Comité consultatif sur le traitement de l'information en matière de recherche (C.C.T.I.R.S.) (CPP ID RCB: 2013-A00129-36); US IRB MPM-SAH Institutional Review Board, Clearwater Florida [IRB number 2013_005]). The study was registered at the ClinicalTrials.gov registration website (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01768494) and the study protocol has been published previously [16] as well as the main analysis [17].

Data collection and processing

We included all consecutive medical ED patients with a history of an acute infection. Patients presenting to the surgical ward and patients <18 years of age were excluded. All procedures were carried out as part of standard patient care. In all patients, we recorded type of infection, collected clinical parameters, pertinent initial vital signs, and laboratory values. Urinary tract infections comprised cystitis, pyelonephritis, prostatitis. Gastrointestinal tract infections mostly comprised gastroenteritis, biliary tract infections, and pancreatitis. Erysipelas displayed the largest part of skin infections, followed by cellulitis. Socio-demographic data were available using routinely gathered information from the hospital electronic medical system used for coding of diagnosis-related groups (DRG) codes. ED nurses were involved making an electronically note of ED care timeliness that included waiting time (time of arrival to time seen by a health care professional), time to drug (time of arrival to time of first drug application) and length of ED stay (LOS, time of arrival to time leaving the ED).

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics including mean with standard deviation, median with interquartile range (IQR) and frequencies on each ED measure. Patients were divided in three groups depending on national setting. To identify independent relationship between hospital- and patient characteristics and ED timeliness univariate regression models were used to assess possible predictors that were further analysed in multivariable models (adjusted for type of infection, age, gender, vital signs, laboratory values [infection/inflammation, renal, electrolytes], comorbidities) using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In case of a dichotomous factor (e.g. no tumor, tumor), the absence of the factor was chosen as reference. In case of a multi-level factor (e.g. infections), the most common one (e.g. pneumonia) was set as reference. Tests were carried out at 5% significance levels. Analyses were performed with STATA 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Population

A total of 544 medical ED patients with a history of an acute infection were included (median age 66 years, 49.3% male gender). The main type of infection at ED admission was pneumonia (40.1%), followed by urinary tract (UTI) (25.9%) and gastrointestinal infections (10.7%). Hypertension (34.6%), diabetes (16.7%), and renal failure (15.8%) were the main comorbidities. 47.2% of patients had two or more criteria for a systematic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and tended to have elevated inflammatory biomarker. A detailed country specific baseline information is visualised in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Parameter | International (n = 544) | CH (n = 213) | F (n = 195) | US (n = 136) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 66.0 (50.0–79.0) | 69.0 (56.0–78.0) | 57.0 (38.0–68.0) | 76.0 (58.0–84.0) | <0.001 |

| Male, No (%) | 268 (49.3) | 125 (58.7) | 95 (48.7) | 48 (35.3) | <0.001 |

| Type of infection, No (%) | |||||

| Pneumonia | 218 (40.1) | 120 (56.3) | 49 (25.1) | 49 (36.0) | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 141 (25.9) | 9 (4.2) | 84 (43.1) | 48 (35.3) | |

| Gastrointestinal tract infection | 58 (10.7) | 29 (13.6) | 22 (11.3) | 7 (5.1) | |

| Skin infection | 53 (9.7) | 32 (15.0) | 17 (8.7) | 4 (2.9) | |

| Others | 74 (13.6) | 23 (10.8) | 23 (11.8) | 28 (20.6) | |

| Comorbidities, No (%) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal disease | 97 (17.8) | 59 (27.7) | 25 (12.8) | 13 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 29 (5.3) | 16 (7.5) | 12 (6.2) | 1 (0.7) | 0.019 |

| Congestive heart failure | 36 (6.6) | 20 (9.4) | 5 (2.6) | 11 (8.1) | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 188 (34.6) | 100 (46.9) | 41 (21.0) | 47 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 47 (8.6) | 27 (12.7) | 17 (8.7) | 3 (2.2) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (16.7) | 38 (17.8) | 26 (13.3) | 27 (19.9) | 0.25 |

| Renal failure | 86 (15.8) | 58 (27.2) | 13 (6.7) | 15 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Tumor | 45 (8.3) | 17 (8.0) | 21 (10.8) | 7 (5.1) | 0.180 |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Heart rate, median (IQR), beats/min | 92 (78–107) | 91 (78–105) | 95 (78–109) | 91 (78–111) | 0.440 |

| Body temperature, median (IQR), °C | 37.3 (36.7–38.1) | 37.8 (37.1–38.6) | 37.2 (36.7–37.9) | 36.8 (36.3–37.3) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation, median (IQR), % | 96 (93–98) | 94 (91–97) | 98 (95–99) | 96 (93–98) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mmHg | 130 (115–148) | 133 (118–148) | 127 (115–144) | 131 (112–155) | 0.180 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mmHg | 76 (65–87) | 76 (67.5–87) | 76 (67–87) | 74 (62–85) | 0.150 |

| SIRS: 0/1 criteria, No (%) | 287 (52.8) | 92 (43.2) | 109 (55.9) | 86 (63.2) | <0.001 |

| SIRS: 2–4 criteria, No (%) | 257 (47.2) | 121 (56.8) | 86 (44.1) | 50 (36.8) | |

| Initial laboratory findings, median (IQR) | |||||

| White blood cells count, cells x 109/L | 10.9 (7.5–14.5) | 11.2 (8.1–14.5) | 10.9 (7.1–14.7) | 10.1 (7.5–14.1) | 0.470 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 110 (30–231) | 103 (33.8–171) | 21 (3–85) | 108.5 (26.5–238) | <0.001 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 137 (134–139) | 137 (134–139) | 137 (135–139) | 138 (135.5–140) | 0.019 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.5 (5.6–8.2) | 6.5 (5.8–8.2) | 6.2 (5.6–8) | 4.8 (4.3–5.3) | 0.570 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 86 (67–116) | 99 (79–140) | 69 (55–93) | 88 (71–133) | <0.001 |

CH, Switzerland; F, France; US, United States of America; IQR, interquartile range; SIRS, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome.

Time to start medication

In general, median time to antibiotic administration was 214 minutes (95% CI: 199, 228), with a maximum of 307 minutes; 95% CI: 263, 328) in France, 230 minutes (95% CI: 210, 264) in Switzerland, and 161 minutes (95% CI: 144, 170) in the US. When looking at gastrointestinal infections in the overall cohort (international), median time to drug (326 minutes [95% CI: 284, 372]) was significantly (p<0.001 [ANOVA]) increased compared to more localised infections such as pneumonia (209 minutes [95% CI: 192, 228]), UTI (204 minutes [95% CI: 169, 233]), and skin infections (207 minutes [95% CI: 168, 253]) (Table 2). We also found significant differences in time to discharge when comparing different infection sites in the overall patient cohort (p = 0.001 [ANOVA]). This was mainly due to patients from the Swiss centre. No differences were observed in time to first physician contact among different infections. Consistently, in all subgroups of acute infections, we found highly significant time differences in starting antibiotics between European and US hospitals.

Table 2. Timeliness of ED care.

| International (n = 544) | CH (n = 213) | F (n = 195) | US (n = 136) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Time (minutes) from hospital admission to [median (95% CI); min, max] | p-value | ||||

| Overall infections (n = 531) | First physician contact | 55 (49, 57); 1, 350 | 62 (59, 69); 6, 350 | 67 (55, 77); 4, 195 | 19 (16, 22); 1, 165 | <0.001 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 214 (199, 228); 26, 476 | 230 (210, 264); 69, 476 | 307 (263, 328); 51, 474 | 161 (144, 170); 26, 425 | <0.001 | |

| ED discharge | 322 (308, 335); 69, 718 | 361 (346, 382); 150, 718 | 319 (300, 340); 69, 653 | 260 (245, 274); 124, 638 | <0.001 | |

| Pneumonia (n = 218) | First physician contact | 53 (44, 58); 1, 350 | 61 (57, 67); 6, 350 | 58 (42, 82); 4, 177 | 21 (14, 23); 1, 136 | <0.001 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 209 (192, 228); 26, 474 | 220 (200, 252); 77, 465 | 310 (220, 359); 51, 474 | 141 (124, 162); 26, 371 | <0.001 | |

| ED discharge | 326 (303, 344); 69, 698 | 350 (331, 367); 167, 698 | 326 (268, 359); 69, 580 | 249 (221, 276); 124, 497 | <0.001 | |

| UTI (n = 141) | First physician contact | 49 (39, 60); 1, 329 | 57 (12, 182); 12, 329 | 78 (63, 88); 13, 195 | 18 (15, 24); 1, 125 | <0.001 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 204 (169, 233); 69, 447 | 246 (142, 345); 97, 377 | 314 (221, 339); 69, 447 | 165 (145, 182); 88, 394 | <0.001 | |

| ED discharge | 294 (274, 318); 75, 639 | 434 (273, 527); 254, 572 | 311 (292, 340); 75, 639 | 247 (224, 268); 143, 523 | 0.001 | |

| GIT (n = 58) | First physician contact | 60 (51, 67); 8, 345 | 64 (57, 82); 25, 345 | 52 (34, 70); 17, 130 | 14 (9, 119); 8, 127 | 0.032 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 326 (284, 372); 93, 476 | 330 (295, 374); 93, 476 | 369 (311, 396); 311, 396 | 228 (218, 248); 218, 248 | 0.213 | |

| ED discharge | 389 (354, 440); 133, 718 | 441 (383, 478); 244, 718 | 374 (299, 440); 133, 653 | 318 (175, 398); 135, 410 | 0.027 | |

| Skin infections (n = 53) | First physician contact | 60 (54, 83); 3, 304 | 74 (57, 114); 13, 304 | 54 (47, 86); 24, 123 | 35 (3, 55); 3, 55 | 0.040 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 207 (168, 253); 69, 468 | 189 (159, 245); 69, 414 | 242 (144, 463); 109, 468 | 257 (250, 264); 250, 264 | 0.231 | |

| ED discharge | 327 (287, 362); 135, 590 | 325 (278, 365); 150, 581 | 357 (279, 424); 135, 590 | 267 (189, 359); 189, 359 | 0.146 | |

| Other infections (n = 74) | First physician contact | 46 (28, 67); 3, 299 | 71 (55, 110); 8, 299 | 70 (32, 88); 9, 153 | 19 (16, 37); 3, 165 | 0.002 |

| Medication (antibiotics) | 187 (169, 238); 39, 473 | 234 (181, 334); 90, 473 | 248 (70, 371); 69, 380 | 165 (129, 199); 39, 425 | 0.077 | |

| ED discharge | 317 (278, 362); 86, 711 | 412 (368, 530); 177, 711 | 282 (213, 368); 86, 613 | 284 (258, 329); 186, 638 | 0.012 |

CH, Switzerland; F, France; US, United States of America; CI, confidence interval; UTI, urinary tract infection; GIT, gastrointestinal tract infection; ED, emergency department.

Timeliness of ED care

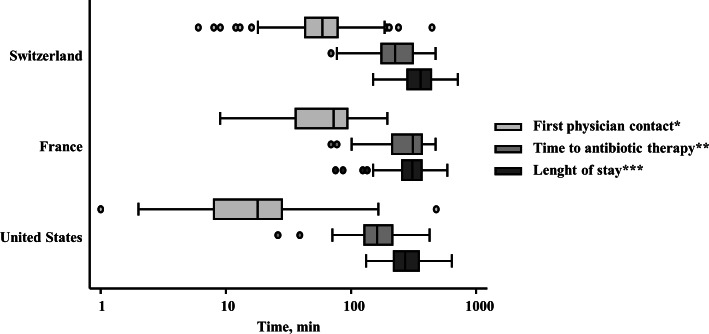

As shown in Fig 1 and Table 2, the overall median waiting time to the first physician contact was 55 minutes (95% CI: 49, 57), notably, there were large differences between the two European hospitals (62 and 67 minutes in Switzerland and France, respectively) and the US hospital (19 minutes; 95% CI: 16, 22). Analog to above mentioned differences in time to start antibiotic therapy, this trend was also obvious investigating subgroups of infections. Finally, international median ED LOS was 322 minutes (95% CI: 308, 335), with a maximum in Switzerland (361 minutes; 95% CI: 346, 382), followed by France (319 minutes; 95% CI: 300, 340), and the US with 260 minutes (95% CI: 245, 274). Corresponding to median time to antibiotics, median ED LOS was larger in gastrointestinal infections than in other infection subgroups. Notable, in French patients with UTI, median time to antibiotic therapy was longer than median ED LOS, resulting from delayed drug administration in clinically stable patients only after ED discharge to the medical ward. All results in detail are shown in Table 2.

Fig 1. Distribution of ED measures of timely care in patients with acute infections across different countries.

The bottom and top of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the hospital-reported mean times for that measure, with the middle line representing the median. * Time of arrival to time seen by a doctor. ** Time of arrival to time being given medication. *** Time of arrival to time leaving the emergency department for home or for an in-hospital bed.

Predictors for delayed antibiotic drug administration

As shown in Table 3, using multivariable adjusted regression analyses, existence of a gastrointestinal tract infection was a significant predictive parameter for delayed start of therapy compared to patients with pneumonia, whereas patients with more localised skin infections, such as erysipelas, tended to results in faster drug administration (e.g. in Switzerland). Focusing demographic characteristics, Swiss patients with an age between 66 and 79 years tended to be at risk for a later onset of adequate therapy using univariate analyses. However, older US patients were treated earlier than younger ones. In multivariable regression models these effects could not be substantiated. Additionally, Swiss patients with a larger inflammation (more positive SIRS criteria) or a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) showed a decreased time to first drug administration. In France, diabetic patients and patients with a hyperglycaemia had to wait longer for an appropriate anti-infective therapy compared to non-diabetic ones. Finally, patients entering the ED during “rush hours” (6–12 pm) tended to wait longer for an appropriate medication.

Table 3. Predictors of delayed antibiotic drug administration.

| Predictor | International (n = 544) | CH (n = 213) | F (n = 195) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Pneumonia | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| UTI | 40.7 (-13.0–94.4) | 0.137 | 7.0 (-89.2–103.2) | 0.886 | 163.6 (-163.3–490.4) | 0.308 |

| GIT | 119.5 (58.0–181.0) | <0.001 | 92.6 (34.4–150.9) | 0.002 | 267.3 (-151.5–686.0) | 0.197 |

| Skin infections | -46.5 (-101.0–8.0) | 0.094 | -65.5 (-118.9–12.1) | 0.016 | 35.6 (-311.1–382.2) | 0.832 |

| Other infections | 31.2 (-33.3–95.8) | 0.341 | 1.1 (-62.0–64.3) | 0.972 | 82.9 (-311.7–477.5) | 0.665 |

| Age ≤50y | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Age ≤66y | 10.4 (-47.5–68.4) | 0.724 | 35.8 (-25.1–96.6) | 0.248 | -295.1 (-487.4–102.8) | 0.005 |

| Age ≤79y | 23.3 (-33.9–80.5) | 0.423 | 30.7 (-29.8–91.2) | 0.318 | -87.1 (-294.1–119.8) | 0.389 |

| Age >79y | -36.6 (-103.9–30.6) | 0.284 | -28.5 (-99.3–42.3) | 0.428 | -120.3 (-403.7–163.1) | 0.385 |

| Female | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Male | -12.8 (-53.7–28.1) | 0.538 | -15.8 (-58.0–26.4) | 0.461 | 43.1 (-130.6–216.7) | 0.610 |

| Day time 0–6 am | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Day time 6–12 am | 26.6 (-55.8–109.0) | 0.525 | 4.9 (-73.7–83.4) | 0.903 | -17.8 (-162.1–126.4) | 0.798 |

| Day time 0–6 pm | 22.2 (-59.0–103.5) | 0.59 | 21.9 (-53.8–97.6) | 0.568 | NA | NA |

| Day time 6–12 pm | 39.5 (-44.2–123.2) | 0.354 | 38.8 (-37.6–115.1) | 0.318 | NA | NA |

| 0 SIRS criteria | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| 1 SIRS criteria | -35.8 (-94.5–23.3) | 0.235 | -38.0 (-96.0–19.9) | 0.197 | -49.9 (-290.8–191.0) | 0.669 |

| 2 SIRS criteria | -24.0 (-82.7–34.6) | 0.42 | -26.8 (-87.1–33.5) | 0.382 | 64.2 (-206.7–335.1) | 0.626 |

| 3/4 SIRS criteria | -59.1 (-120.9–2.6) | 0.06 | -60.7 (-123.3–2.0) | 0.058 | 98.4 (-195.3–392.1) | 0.492 |

| ≤130mmHg systolic | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| >130mmHg systolic | 11.1 (-32.1–54.2) | 0.614 | 9.9 (-34.0–53.8) | 0.656 | -164.3 (-391.3–62.4) | 0.146 |

| ≤76mmHg diastolic | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| >76mmHg diastolic | -5.7 (-49.7–38.3) | 0.799 | 9.4 (-34.1–52.9) | 0.669 | 57.0 (-121.9–236.0) | 0.513 |

| Sodium (136–146mmol/L) | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Sodium (<136, >146mmol/L) | -21.9 (-61.9–18.1) | 0.281 | -20.4 (-60.3–19.5) | 0.315 | -23.8 (-205.3–157.6) | 0.786 |

| Glucose (4–7mmol/L) | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Glucose (<4, >7mmol/L) | -26.6 (-67.9–14.6) | 0.205 | -17.6 (-60.8–25.5) | 0.421 | 203.0 (-2.1–408.2) | 0.052 |

| Creatinine (≤86mg/L) | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Creatinine (>86mg/L) | 21.4 (-24.3–67.2) | 0.357 | 6.8 (-40.1–53.6) | 0.776 | 43.7 (-130.0–217.4) | 0.604 |

| CRP (≤69mg/L) | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| CRP (>69mg/L) | 13.3 (-25.7–52.3) | 0.502 | 1.6 (-37.9–41.2) | 0.935 | 58.9 (-98.6–216.4) | 0.443 |

| No obesity | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Obesity | -11.2 (-70.0–47.5) | 0.707 | 0.1 (-54.1–54.3) | 0.998 | NA | NA |

| No CAD | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| CAD | -13.6 (-83.4–56.1) | 0.701 | 11.7 (-57.0–80.3) | 0.738 | -137.7 (-476.1–200.7) | 0.405 |

| No CHF | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| CHF | 27.7 (-39.3–94.6) | 0.417 | 22.0 (-42.6–86.6) | 0.502 | 239.6 (-255.5–734.6) | 0.324 |

| No COPD | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| COPD | -44.7 (-101.3–11.8) | 0.12 | -66.2 (-120.2–12.3) | 0.016 | -51.1 (-421.1–319.0) | 0.776 |

| No tumor | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Tumor | 27.6 (-35.1–90.2) | 0.387 | 40.4 (-26.1–106.9) | 0.232 | -75.0 (-339.2–189.1) | 0.559 |

| No diabetes | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Diabetes | 27.8 (-23.5–79.1) | 0.287 | -9.1 (-64.6–46.5) | 0.747 | 222.3 (-0.5–445.0) | 0.050 |

| No GIT disease | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| GIT disease* | -1.6 (-46.3–43.0) | 0.942 | -8.0 (-50.4–34.3) | 0.709 | 252.0 (-36.1–540.0) | 0.083 |

| No hypertension | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Hypertension | 29.4 (-10.4–69.3) | 0.146 | 38.0 (-1.8–77.9) | 0.061 | 19.3 (-168.0–206.6) | 0.831 |

| No renal failure | reference | - | reference | - | reference | - |

| Renal failure | -30.3 (-79.0–18.3) | 0.22 | -12.6 (-61.3–36.1) | 0.609 | -59.6 (-297.9–178.7) | 0.607 |

CH, Switzerland; F, France; US, United States of America; CI, confidence interval; UTI, urinary tract infection; GIT, gastrointestinal tract; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; CRP, C-reactive protein; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable; US data not applicable due to small patient number.

Discussion

In this international prospective observational cohort study of ED patients with a history of an acute infection we compared predictors for delay in initial care. In a second step, timeliness of ED care was investigated. This study was conducted in three tertiary hospitals with a different ED management (e.g. triage system), health care system, and socio-demographic spectrum (e.g. culture, race).

In general, we found a median ED LOS of about 5.5 hours that is higher compared to previously published data in France and the US [11, 18, 19], in Switzerland there exists no comparable data. The main reason for these observation is that most patients with acute infections have a diffuse and non-specific symptomatic (e.g. fever, shivering, fatigue) and therefore require supplementary time for diagnostic- and therapeutic steps. Most previous publications investigated unselected ED patients independent of discipline, mirroring a fuzzy image of patient subgroups like acute infectious diseases [7, 20, 21].

Waiting time, time to drug, and ED LOS were shorter in the US compared to the European centres. In addition to a slightly lower acuity and severity of admitted US patients (lower body temperature, less SIRS criteria), and significant differences in socio-demographics of ED patients among all centres (US population was older and more females), implementation of clinical pathways and fast-track admission in the US could be a possible explanation for a superior ED timeliness. Yet, baseline crowding status of the participating hospitals was not available and we can thus not exclude bias in this regard. Such information should be included in future larger trials. Another explanation may relate to the high administrative work associated with ED admission in Switzerland [22], resulting in a prolonged time from therapy to ED discharge.

Mainly, the presence of a gastrointestinal tract infection was a significant predictor of a delayed initiation of an adequate therapy, likely because abdominal site infection may be diagnostically more obscure and symptoms masked or atypical. In contrast, more localised infections (e.g. skin infections)–requiring less extended supplementary diagnostics–tended to be treated faster, also resulting in a decreased ED LOS. Severe cases (more positive SIRS criteria, relevant comorbidities such as COPD) were treated significantly faster in the Swiss population. In France, diabetic patients showed longer waiting times, potentially mirroring a more polymorbid (e.g. metabolic syndrome) patient population. Due to small the small number of patients included from the US site, we focused on the comparison of the two European centres.

As a second point, analogous to previous literature [20, 23, 24], length of stay was increased in Swiss elderly patients, suggesting a higher complexity due to comorbidities and a more prolonged decision-making process than in younger ones. Finally, ED patients presenting between 6:00 and 12:00 p.m. tended to have a longer ED stay, correlating with increased patient admissions [25].

Our study has some important limitations. First, this was an observational study that was focusing on the question if an improved initial triage of patients at the earliest stage of ED admission with incorporation of a triage system, initial clinical parameters, vital signs, and prognostic blood markers will improve patient triage [16, 26]. Second, we investigated a small patient sample, with partially incomplete available data, limiting subgroup analyses`conclusions. Third, we did not take into account the number of medical and non-medical staff, available in these EDs to take care of the patients. Last, we did not consider in-hospital bed capacity that might have had decelerating effects on transfer from the ED to the medical ward. All these limitations could have implications in interpreting our results and may limit external validity. However, we performed an international multicentre study with many available ED parameters, and updated reasons for ED consultation, displaying a major strength of this study.

To further decrease time to first physician contact and time to antibiotics, especially in urgent patients at risk for worse outcome, fast and high sensitive point-of-care testing (POCT) devices measuring prognostic biomarkers could be a promising tool [27]. Herein, a new prognostic biomarker (proadrenomedullin, ProADM) [28] is supposed to support differentiating urgent from non-urgent patients showing non-conclusive clinical symptoms and to improve existing triage systems. Alternatively, as previously published by Chartier et al., ED flow can be significantly improved by re-purposing a fraction of existing staff, resources, and infrastructure for patients with lower acuity presentations [29]. From the initial triages perspective, a recent study that implemented a computer-assisted triage system using acute physiology, pre-existing illness and mobility showed a measurable impact on cost of care for patients with very low risk of death. Patients were safely discharged earlier to their own home and the intervention was cost-effective [30]. Finally, another study investigated the effect of implementation of a triage/treatment pathway in adult patients with cancer and febrile neutropenia improving initial ED triage. In this study, antibiotic delays were reduced and quality of care for patients was improved [31]. To definitively proof effectiveness and safety of all these promising tools, well-powered large randomized controlled trials are inevitable.

Conclusion

Time to adequate drug administration and ED LOS were principally associated with the clinical picture and the need for diagnostics. In Switzerland, older patients were treated later, suggesting a higher complexity–rudimentary seen in French diabetic patients—with a longer clinical decision-making process than in younger patients. Even, if necessary to optimise evaluation and reach the best final disposition decision, can lengthen the overall time spent in the ED.

This international study provides new insights into the relative effect of diffuse clinical pictures, comorbidities, and demographics on international ED timeliness. Our results suggest that new strategies to reduce time to antibiotic medication and ED LOS–especially in patients with an acute infection—should include suitable advices (e.g. POCT) for ancillary biomarker measurement.

Acknowledgments

We thank the emergency room (Ulrich Buergi, Petra Tobias and their team), medical clinic (nursing department: Susanne Schirlo) and central laboratory staff (Martha Kaeslin, Renate Hunziker), the Study Nurses of the TRIAGE study (Katharina Regez, Ursula Schild, Merih Guglielmetti, Zeljka Caldara), and the IT department (Roger Wohler, Kurt Amstad, Ralph Dahnke, Sabine Storost).

The TRIAGE study group includes further members from the University Department of Internal Medicine, Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland (Ulrich Buergi, MD, Petra Tobias, RN, Eva Grolimund, MD, Ursula Schild, RN, Zeljka Caldara, RN, Katharina Regez, RN, Martha Kaeslin, Ursina Minder, RN, Renate Hunziker, RN, Andriy Zhydkov, MD, Timo Kahles, MD, Krassen Nedeltchev, MD, Petra Schäfer-Keller, PhD) the Clinical trials unit University hospital Basel (Stefanie von Felten, PhD), the Institute of Nursing Science, University Basel, Switzerland (Sabina De Geest, PhD); the Department of Psychology, University of Berne (Pasqualina Perrig-Chiello, PhD); Department of Emergency Medicine, Hôpital Pitié-Salpétriêre, Paris, France; (Anne-Laure Philippon, David Pariente, Jérome Bokobza, Adeline Aubry, Nadia De Tommaso, Ilaria Cherubini, Aline Lecocq, Kahina Kachetel); the Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, FL, USA (Rebecca Virgil, RN, Jo Simpson, RN).

Leading author of the TRIAGE Study group: Prof. Dr. Philipp Schuetz, MD, MPH.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DRG

diagnosis-related groups

- ED

emergency department

- IQR

interquartile range

- LOS

length of stay

- POCT

point-of-care testing

- ProADM

proadrenomedullin

- SIRS

systematic inflammatory response syndrome

- US

United States

- UTI

urinary tract infection

Data Availability

Due to lack of informed patient consent, data is available upon request to Prof. Schuetz at schuetzph@gmail.com.

Funding Statement

Thermofisher provided an unrestricted research grant for this study. PS is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Professorship, PP00P3_150531 / 1). This study was also supported by the Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften (SAMW). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Di Somma S, Paladino L, Vaughan L, Lalle I, Magrini L, Magnanti M. Overcrowding in emergency department: an international issue. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2015;10(2):171–5. Epub 2014/12/03. 10.1007/s11739-014-1154-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, Alkemade AJ, Al Shabanah H, Anderson PD, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1358–70. Epub 2011/12/16. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute Of M. IOM report: the future of emergency care in the United States health system. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(10):1081–5. Epub 2006/10/04. 10.1197/j.aem.2006.07.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(2):126–36. Epub 2008/04/25. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Cutrona SL, Bor DH, et al. Waits to see an emergency department physician: U.S. trends and predictors, 1997–2004. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):w84–95. Epub 2008/01/17. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w84 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herring A, Wilper A, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Espinola JA, Brown DF, et al. Increasing length of stay among adult visits to U.S. Emergency departments, 2001–2005. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(7):609–16. Epub 2009/06/23. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00428.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horwitz LI, Green J, Bradley EH. US emergency department performance on wait time and length of visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(2):133–41. Epub 2009/10/03. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy ML, Zeger SL, Ding R, Levin SR, Desmond JS, Lee J, et al. Crowding delays treatment and lengthens emergency department length of stay, even among high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):492–503 e4. Epub 2009/05/09. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, Baxt WG, Lee H, Phillips C, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510–6. Epub 2007/10/05. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fee C, Weber EJ, Maak CA, Bacchetti P. Effect of emergency department crowding on time to antibiotics in patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):501–9, 9 e1. Epub 2007/10/05. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capuano F, Lot AS, Sagnes-Raffy C, Ferrua M, Brun-Ney D, Leleu H, et al. Factors associated with the length of stay of patients discharged from emergency department in France. European journal of emergency medicine: official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2015;22(2):92–8. Epub 2014/02/27. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000109 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(1):1–5. Epub 2007/10/05. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, Epstein S, Handel D, Hwang U, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10. Epub 2008/11/15. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu SW, Thomas SH, Gordon JA, Hamedani AG, Weissman JS. A pilot study examining undesirable events among emergency department-boarded patients awaiting inpatient beds. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):381–5. Epub 2009/03/24. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.02.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulstad EB, Sikka R, Sweis RT, Kelley KM, Rzechula KH. ED overcrowding is associated with an increased frequency of medication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(3):304–9. Epub 2010/03/13. 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuetz P, Hausfater P, Amin D, Haubitz S, Fassler L, Grolimund E, et al. Optimizing triage and hospitalization in adult general medical emergency patients: the triage project. BMC emergency medicine. 2013;13(1):12 Epub 2013/07/05. 10.1186/1471-227X-13-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuetz P, Hausfater P, Amin D, Amin A, Haubitz S, Faessler L, et al. Biomarkers from distinct biological pathways improve early risk stratification in medical emergency patients: the multinational, prospective, observational TRIAGE study. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):377 Epub 2015/10/30. 10.1186/s13054-015-1098-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le ST, Hsia RY. Timeliness of care in US emergency departments: an analysis of newly released metrics from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(11):1847–9. Epub 2014/09/16. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3431 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullins PM, Pines JM. National ED crowding and hospital quality: results from the 2013 Hospital Compare data. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):634–9. Epub 2014/03/19. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casalino E, Wargon M, Peroziello A, Choquet C, Leroy C, Beaune S, et al. Predictive factors for longer length of stay in an emergency department: a prospective multicentre study evaluating the impact of age, patient's clinical acuity and complexity, and care pathways. Emergency medicine journal: EMJ. 2014;31(5):361–8. Epub 2013/03/02. 10.1136/emermed-2012-202155 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Linden N, van der Linden MC, Richards JR, Derlet RW, Grootendorst DC, van den Brand CL. Effects of emergency department crowding on the delivery of timely care in an inner-city hospital in the Netherlands. European journal of emergency medicine: official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2015. Epub 2015/04/02. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000268 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer BR, B.; Golder, L.; Longchamp, C. Administrativer Aufwand für Ärzte steigt weiter an, http://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf17/SAEZ_1_Befragung_gfs.bern_D.pdf, Access Date: 18.01.2016 2015 [cited 2016 18.01.2016]. Available: http://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf17/SAEZ_1_Befragung_gfs.bern_D.pdf.

- 23.Pines JM, Decker SL, Hu T. Exogenous predictors of national performance measures for emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):293–8. Epub 2012/05/26. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitz LI, Bradley EH. Percentage of US emergency department patients seen within the recommended triage time: 1997 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1857–65. Epub 2009/11/11. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derose SF, Gabayan GZ, Chiu VY, Yiu SC, Sun BC. Emergency department crowding predicts admission length-of-stay but not mortality in a large health system. Med Care. 2014;52(7):602–11. Epub 2014/06/14. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000141 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner D, Renetseder F, Kutz A, Haubitz S, Faessler L, Anderson JB, et al. Performance of the Manchester Triage System in Adult Medical Emergency Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Emerg Med. 2015. Epub 2015/10/16. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.09.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutz A, Hausfater P, Oppert M, Alan M, Grolimund E, Gast C, et al. Comparison between B.R.A.H.M.S PCT direct, a new sensitive point-of-care testing device for rapid quantification of procalcitonin in emergency department patients, and established reference methods—a prospective multinational trial. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015. Epub 2015/10/02. 10.1515/cclm-2015-0437 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang DT, Angus DC, Kellum JA, Pugh NA, Weissfeld LA, Struck J, et al. Midregional proadrenomedullin as a prognostic tool in community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136(3):823–31. Epub 2009/04/14. 10.1378/chest.08-1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chartier L, Josephson T, Bates K, Kuipers M. Improving emergency department flow through Rapid Medical Evaluation unit. BMJ quality improvement reports. 2015;4(1). Epub 2016/01/07. 10.1136/bmjquality.u206156.w2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subbe CP, Kellett J, Whitaker CJ, Jishi F, White A, Price S, et al. A pragmatic triage system to reduce length of stay in medical emergency admission: feasibility study and health economic analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(9):815–20. Epub 2014/07/22. 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keng MK, Thallner EA, Elson P, Ajon C, Sekeres J, Wenzell CM, et al. Reducing Time to Antibiotic Administration for Febrile Neutropenia in the Emergency Department. Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;11(6):450–5. Epub 2015/07/30. 10.1200/JOP.2014.002733 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to lack of informed patient consent, data is available upon request to Prof. Schuetz at schuetzph@gmail.com.