Abstract

Declining fertility in China has raised concerns about elderly support, especially when public support is inadequate. Using rich information from the nationally representative China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) baseline survey, we describe the patterns of current living arrangements of the Chinese elderly and investigate their determinants and correlation with intergenerational transfers. We find that roughly 41% of Chinese aged 60 and over live with an adult child; living with a male adult child being strongly preferred. However another 34% have an adult child living in the same immediate neighborhood and 14% in the same county; only 5% have an adult child with none of them living in the same county. At the same time, a large fraction of the elderly, 45% in our sample, live alone or with only a spouse. In general, women, those from western provinces, and those from rural areas are more likely to live with or close to their adult children than their corresponding counterparts, but different types of intergenerational transfers play a supplementary role in the unequal distribution of living arrangements. Among non-co-resident children, those living close by visit their parents more frequently and have more communications by other means. In contrast, children who live farther away are more likely to send financial and in-kind transfers and send larger amounts.

Keywords: living arrangement, co-residence, proximity of children, CHARLS

1. Introduction

The population is aging rapidly in China. In 2000, people 60 and older accounted for 10% of the population, rising to 13.3% in 2010, and is expected to reach 30% in 2050 (United Nations 2002). Unlike in developed countries where almost all the elderly have access to publicly provided social security, the family has been the main source of support for Chinese elderly, especially in rural areas, where the majority of Chinese elderly reside. In recent decades, however, the number of children has declined rapidly, as the total fertility rate has fallen from 6 at the end of the 1960s to under 2 today. In addition, rural young people have moved into cities in large numbers as the greatest migration in world history. These trends have raised questions regarding the reliability of families to provide support for the elderly in China.

This concern is echoed by empirical evidence that shows that Chinese elderly are increasingly living alone or only with a spouse. Palmer and Deng (2008), using the China Household Income Projects (CHIPs) data collected in 1988, 1995 and 2002, show that persons 60 and older, especially those in urban areas, are increasingly more likely to live with their spouses than in intergenerational households with their children. They conjecture that this trend is due to the increasing availability of pensions; however, rapidly rising incomes and savings over this period, plus improved health over younger birth cohorts no doubt contribute to this trend as well. Meng and Luo (2008), using the urban sample of CHIP, also show that the fraction of elderly living in an extended family in urban China declined significantly over the study period. They also cite 1990s housing reform, which increased housing availability and hence allowed elders who preferred to live alone to do so. Using population census data of 1982, 1990 and 2000, Zeng and Wang (2003) present a similar pattern and attribute it to tremendous fertility decline and significant changes in social attitudes and population mobility.

What do we infer about the welfare of the elderly from this trend of living away from children? Benjamin, Brandt, and Rozelle (2000) find that elderly persons living alone are worse off in terms of income than those living in an extended household, and the welfare implication is even stronger when we recognize that elderly in simple households also work more. Sun’s (2002) research on China’s contemporary old age support suggests that living away from children prevents the elderly from receiving help with their daily activities. Silverstein, Cong, and Li (2006) find for a sample of rural Chinese elderly in Anhui province, that parents who live with grandchildren, either in three or skipped-generation households, have better psychological well-being than those who live by themselves, or even with children, but without grandchildren.

A similar trend of elderly living alone has been noted in the United States, where the proportion of elderly living independently increased markedly in the twentieth century (Costa 1998; McGarry and Schoeni 2000; Engelhardt and Gruber 2004). While the literature has noted that living alone is associated with poverty, a higher level of depression symptoms and more chronic diseases (Agree 1993; Saunders and Smeeding 1998; Victor et al. 2000; Kharicha et al. 2007; Wilson 2007; Greenfield and Russell 2011), the economic literature has in general viewed this trend as utility enhancing for the elderly, because independence, or privacy, is a normal good (Doty 1986; Martin 1989; Kotlikoff and Morris 1990; Mutchier and Burr 1991; Tomassini et al. 2004). For example, Costa (1998) finds that prior to 1940, rising income substantially increased demand for separate living arrangements and therefore was the most important factor enabling the elderly to live alone in the United States. McGarry and Schoeni (2000) analyze the causes of the increasing share of elderly widows living alone between the 1940s and the 1990s, and indicate that income growth, especially increased social security benefits, was the single most important factor causing the change in living arrangements, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the rise in living alone. With more recent data from the Current Population Survey 1980–1999, Engelhardt and Gruber (2004) find that living arrangements are still very income sensitive, particularly for widows and divorcees, and conclude from the results that privacy is valued by the elderly and their families.

What we find lacking in the literature is that living alone and getting support from the family are viewed as mutually exclusive, whereas several studies indicate that families do not need to cohabitate in order for children to provide support to elders. A study by Zimmer and Korinek (2008) shows that a large fraction of Chinese elderly who do not live with their adult children have children living within the same neighborhood. Bian, Logan, and Bian (1998) find a similar co-residence pattern using data from two cities (Shanghai and Tianjin) in 1993. Although most elderly still lived with their children, many of them also had children living nearby who maintained frequent contact and provided regular non-financial assistance. Giles and Mu (2007) also provide some evidence for such conditions of living and assistance, though it is not the focus of their article.

In this article, we further examine how Chinese families reconcile these two objectives using the first truly nationally representative survey of the Chinese elderly, the national baseline wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). We find that many Chinese elderly live alone or only with a spouse. However, most of them have an adult child living nearby to guarantee care when needed. The first goal of this article is to depict an updated and broad picture of the living arrangements of the Chinese elderly and to look at how many elderly parents living alone actually have adult children living nearby. Second, we aim to shed some light on what determines the living arrangements of Chinese families with elderly parents, especially the proximity of adult children. Finally, we examine the relationships between living arrangements and other forms of elderly support including the frequency of visits and financial transfers.

We find that the increasing trend in living alone is accompanied with a rise in living close to each other. This type of living arrangement helps to resolve the conflict between the desire for privacy/independence and the need for familial support. This is confirmed in further investigation: adult children living close by visit their parents more frequently. We also find that adult children who live far away provide a larger amount of net transfers to their parents, a result consistent with sharing responsibilities among siblings. Sons, especially last- and first-borns, are more likely to live with their parents than daughters or middle-born sons. Adult children with higher incomes are more likely to live further away, that is, out of the county, but also are more likely to provide larger and more frequent financial transfers.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The next section describes our data. Section three presents the patterns of China’s elderly living arrangements. Section four discusses the empirical results of the determination of elderly living arrangements. Section five concludes.

2. Data

We use the CHARLS 2011–2012 national baseline data, which is described in detail in Zhao et al. (2013). CHARLS was designed after the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the USA as a broad-purposed social science and health survey of the elderly in China. The national baseline was conducted July 2011–March 2012 and represented people aged 45 and over living in 150 counties in 28 provinces across China. CHARLS randomly selected 150 county-level units by PPS (probability proportional to size), stratified by region, urban/rural and county-level GDP.1 Within each county-level unit, CHARLS randomly selected three village-level units (villages in rural areas and urban communities in urban areas) by PPS as primary sampling units (PSUs). Within each PSU, 80 dwellings were randomly selected from a complete list of dwelling units generated from a mapping/listing operation, using augmented Google earth maps, together with considerable ground checking. In situations where more than one age-eligible household lived in a dwelling unit, CHARLS randomly selected one. From this sample for each PSU, the proportion of households with age-eligible members was determined, as was the proportion of residences that were empty. From these proportions, and an assumed response rate, we selected households from our original PSU frame to obtain a target number of 24 age-eligible households per PSU. Thus the final household sample size within a PSU depended on the PSU age-eligibility and empty residence rates. Within each household, one person aged 45 and older was randomly chosen to be the main respondent and their spouse was automatically included. Based on this sampling procedure, one or two individuals in each household were interviewed depending on marital status of the main respondent. The total sample size is 10,257 households and 17,708 individuals. The overall household response rate was 80.5%: 71.7% in urban areas and 95.1% in rural areas. These response rates are higher than the rates in the USA and Europe for a first wave of population-based surveys.

Following the protocols of the HRS international surveys, the CHARLS main questionnaire in the 2011–2012 survey consists of seven modules, covering demographics, family background, health status (including physical and psychological health, cognitive functions, lifestyle and behaviors), socioeconomic status (SES) and environment (community questionnaire and county-level policy questionnaire) (Zhao et al. 2013). All data were collected in face-to-face, computer-aided personal interviews (CAPI).

In the family module, all CHARLS respondents were asked how many living children they have. For each child, CHARLS collected information on a variety of characteristics: sex; birth year and month; biological relationship with respondent; and residence. The residence of the child was categorized as follows: (1) this household; (2) adjacent dwelling or same courtyard; (3) another house in this village or community; (4) another village or community in this county or city; (5) another county or city in this province; (6) another province; and (7) abroad. This information enables us to describe the living arrangements in a more detailed way than the previous literature. Other information collected includes each child’s education level, income category (an ordinal measure), marital status, working status, occupation and number of children. For parents (respondents), we have detailed demographic information, income and wealth measures and rich health measures. More details about the variables we use are provided in section four. With this rich pool of information, we used multivariate estimation to identify the determinants of elderly living arrangements and investigate joint decisions between parents and children.

3. Patterns in elderly living arrangements

We examined the living arrangements of elderly respondents, similar to the previous literature, but with special consideration to the proximity of their adult children. We focused on adult children because we wanted to explore the degree of support given by children to their parents, and such support is largely provided by adult children. We used 25 years as our cutoff age for adult children because we did not want to include students, since they are not in a good position to provide support, especially financial support. We divided elderly living arrangements into seven categories, not all of them mutually exclusive: (1) living alone; (2) living with spouse only; (3) living with one or more adult children; (4) living alone, but with one or more adult children in the same village or community; (5) living alone, but with one or more adult children in the same county; (6) living alone without any adult child in the same county; and (7) having no adult children. We also examined and classified respondents, if they live with others besides their spouse, as living with children-in-law but not with an adult child (who may be working in a different place), living with grandchildren but not with adult children or children-in-law and other living relationships.

Table 1 presents an overall picture of the elderly households’ living arrangements at the time of the survey.2 We restricted our attention to elderly individuals who are 60 and older.3 From this table, we can see that 9% of all elderly respondents surveyed live alone and another 36% live with their spouse only. Some of the elderly who live independently are physically robust; that is, they need less help with activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), while others are frail and more likely to be poor (CHARLS Research Team 2013). The fraction living alone or with their spouse only is considerably higher than found in other Asian countries, which averages only 25% (United Nations 2011). For example, in the pilot survey of the Longitudinal Study of Aging in India (LASI), only 17% of the elderly live alone or with their spouse only (Arokiasamy et al. 2013). In the CHARLS data some 41% of all elderly respondents are living with one or more adult children (43% live with any child, see below). A small number of them (5.6% of all respondents), mostly men, have no adult children. Another 7.2% live with grandchildren, but not adult children. These grandchildren span in age from adults who can care for their grandparents to the very young, who are being cared for by their grandparents. Another 2.4% live with children-in-law but not their adult children. Some 3.9% of our sample elderly live with others. Of these, 60%, or 2.0% of the total, are living with children aged less than 25. Of those who have an adult child or children but do not live with them, 64.6% (34.3/53.1) have at least one adult child living in the same village/community, meaning that they should have access to care. Even for those without access to an adult child in the same village, 73.9% (13.9/18.8) have at least one adult child living in the same county. Only 5.2% (4.9/94.4) of elderly with adult children, and 10.5% (4.9%+5.6%) of all elderly do not have an adult child within the same county. This indicates that the proximity of the children should be taken into account as part of the care children are able to supply to elderly parents.

Table 1.

Living arrangements of elderly households (%) weighted.

| Total | Female | Male | Rural | Urban | East | Middle | West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live in a single person household | 9.0 | 11.2 | 6.7 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 11.2 | 8.1 | 7.4 |

| Live with spouse only | 36.2 | 32.2 | 40.4 | 34.1 | 38.5 | 44.3 | 37.4 | 26.1 |

| Live with children-in-law but not children | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| Live with grandchildren but not children and children-in-law | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 9.0 | 7.9 |

| Live with others | 3.9 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 4.2 |

| Live with one or more adult children | 41.3 | 43.6 | 38.8 | 42.2 | 40.3 | 34.3 | 38.9 | 51.2 |

| Do not live with adult children, but have one or more adult children in the same village/community | 34.3 | 34.9 | 33.6 | 36.1 | 32.3 | 38.8 | 36.7 | 27.0 |

| Do not live with adult children, but have one or more adult children in another village/community in the same county | 13.9 | 13.1 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 16.2 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 11.3 |

| Do not live with adult children, and have no child in the same county | 4.9 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Have no adult child | 5.6 | 4.4 | 6.9 | 4.5 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 3.5 | 4.9 |

| Observations | 7358 | 3693 | 3664 | 4426 | 2932 | 2459 | 2389 | 2510 |

Notes:

Sample: CHARLS respondents and spouses 60 or above.

Rotating parents and couples in separation are excluded.

‘No adult child’ is defined as having no child 25 years old or above.

In general, women are a little more likely to live with or close to their adult children than men; those from western provinces and from rural areas are slightly more likely to do so than those from eastern and middle provinces and urban areas. Meanwhile, men and those from eastern provinces and urban areas are more likely to be without adult children.

Figure 1 shows the age patterns of elderly living arrangements without taking account of how close the adult children live. Two lines, one living alone or with spouse only, the other living with one or more adult children, are displayed. We see that the probability of living alone or only with a spouse increases with age until 77–78 and then decreases, and the probability of living with adult children declines and then increases correspondingly. This pattern reflects that adult children may move away from their parents as they age but they move back or have their parents move in with them to meet their elderly parents’ needs for care. The likelihood of living alone as age increases (up to a point) does not deviate from worldwide trends. Based on a comprehensive dataset collected from 50 countries across five continents, the United Nations (2005) shows that the likelihood of living alone actually increases at advanced ages.

Figure 1.

Living arrangements of Chinese elderly.

Note: Bandwidth (bw) = 0.4; wt = individual weight.

Source: CHARLS 2011.

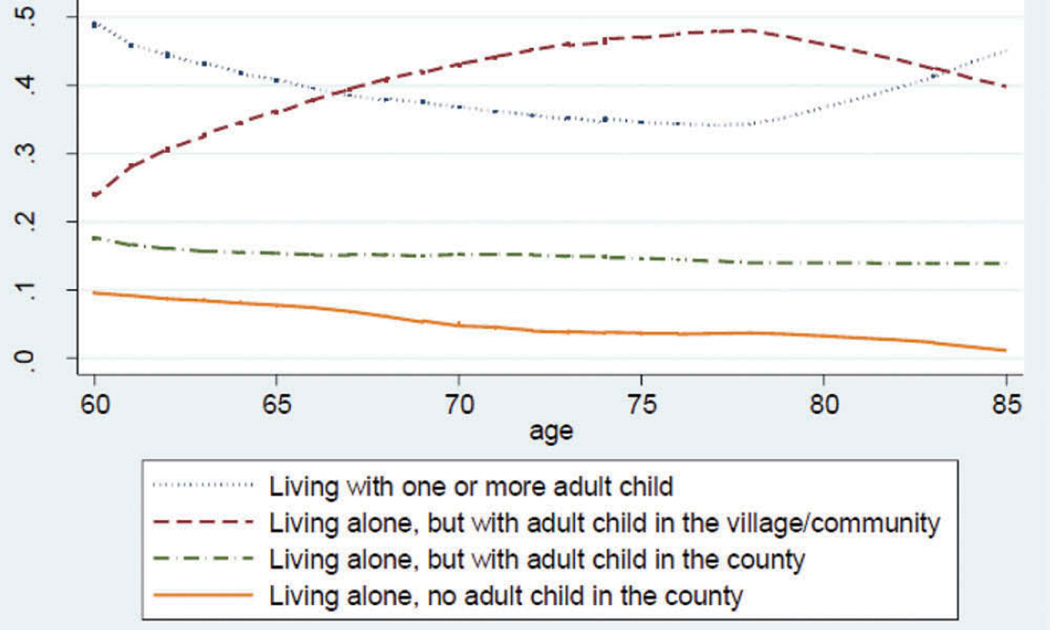

A different story emerges when we examine the patterns in more detail by taking into consideration the proximity of adult children. As shown in Figure 2, the decline in the proportion of co-residency by age is fully compensated by the increasing share of proximate adult child(ren). The likely story is that when children mature and achieve independence from their parents, they do not abandon their parents. They move out but live nearby so that the care needs of their parents are met. This is further evidence that looking at the proximity of adult children is valuable in understanding the welfare of the elderly.

Figure 2.

Living arrangements and proximity of children.

Note: bw = 0.4; wt = individual weight.

Source: CHARLS 2011.

Table 2 shows characteristics of the respondents (parents) according to the living arrangements of their households, that is, whether they live with an adult child, have an adult child living in the same county or have an adult child living far away.4 If the respondents in the household were a couple, the maximum age, maximum education and health condition of the person in worse health were reported because these measures may be more relevant to living arrangement decisions. Nine percent of households had a single male respondent, 23% had a single female respondent and the remaining 68% were couples. On average, the maximum age of elderly parents was 70. Hence the average parent was born around 1942, which means they would have been 38 in 1980 when the One-Child Policy started and in their late 20s and early 30s in the early 1970s when family planning programs were established. This absence of exposure to stronger family planning policies is reflected in the number of surviving children (total children), which is 3.29. Almost half, 48%, were from urban areas. Regarding health status, 22% rated their health as being very poor. Thirty-seven percent reported having ADL or IADL difficulties. The education level of the elderly parents was generally very low. Twenty-five percent are illiterate, and 45% have a primary education either formally or informally.5 The annual pre-transfer income for the elderly household is 7981 RMB, but with a very large standard deviation. Seventy-two percent of the elderly parents currently own a house. Parents living with an adult child tend to be widowed, female, illiterate and less likely to own their own house.

Table 2.

Parent characteristics by living arrangements (weighted).

| All | Living with at least one adult child |

Living alone but with one or more adult child in the country |

Living alone but without any adult child in the country |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Maximum Age | 69.64 (0.13) |

68.99 (0.21) |

70.54 (0.18) |

66.19 (0.42) |

0.00 |

| Single Man | 0.09 (0.00) |

0.10 (0.01) |

0.08 (0.01) |

0.08 (0.02) |

0.08 |

| Single Woman | 0.23 (0.01) |

0.27 (0.01) |

0.20 (0.01) |

0.13 (0.03) |

0.00 |

| # of Children | 3.29 (0.03) |

3.17 (0.04) |

3.49 (0.03) |

2.40 (0.09) |

0.00 |

| Urban | 0.48 (0.01) |

0.47 (0.01) |

0.49 (0.01) |

0.43 (0.03) |

0.29 |

| Maximum Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 0.25 (0.01) |

0.27 (0.01) |

0.24 (0.01) |

0.17 (0.03) |

0.00 |

| Primary | 0.45 (0.01) |

0.43 (0.01) |

0.46 (0.01) |

0.48 (0.03) |

0.29 |

| Middle School & Above | 0.30 (0.01) |

0.29 (0.02) |

0.31 (0.01) |

0.35 (0.03) |

0.21 |

| Income Wealth | |||||

| Own any House | 0.72 (0.01) |

0.45 (0.01) |

0.96 (0.00) |

0.90 (0.03) |

0.00 |

| Household Pre-transfer Income per Capita (1000 RMB) |

7981.35 (289.72) |

7871.86 (570.48) |

8056.96 (297.45) |

8090.03 (905.67) |

0.96 |

| Health | |||||

| Worse SRH is very Poor | 0.22 (0.01) |

0.22 (0.02) |

0.22 (0.01) |

0.26 (0.05) |

0.78 |

| Any ADL/IADL Difficulty | 0.37 (0.01) |

0.41 (0.02) |

0.35 (0.02) |

0.23 (0.05) |

0.00 |

| Observations | 4697 | 1980 | 2914 | 303 |

Notes:

Sample: CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above and with any child aged 25 and above).

P-values of testing whether the means are equal are provided in the last column.

Robust standard errors in brackets.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the respondents’ adult children aged 25 and older. On average, they are 41.5 years old, with 47% being daughters and 53% sons. The average number of their children (i.e. grandchildren of the CHARLS respondents) younger than 16 is 1.0. The educational level of the children is much higher than their elderly parents. Only 9% are illiterate, 39% have completed primary school, 31% have a middle school education and the remaining 20% have an education of high school and above.

Table 3.

Children’s characteristics by living arrangements (weighted).

| All | Co-resident | Nearby child |

Non-nearby child |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Child Age | 41.46 (0.11) |

37.82 (0.19) |

42.73 (0.13) |

40.04 (0.17) |

0.00 |

| Daughters | 0.47 (0.00) |

0.15 (0.01) |

0.54 (0.01) |

0.48 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Fraction Married | 0.92 0.00 |

0.77 (0.01) |

0.95 0.00 |

0.91 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| # of Grandchild Younger than 16 | 1.00 (0.02) |

1.41 (0.04) |

0.89 (0.02) |

1.16 (0.04) |

0.00 |

| Rural Hukou | 0.74 (0.01) |

0.77 (0.01) |

0.75 (0.01) |

0.70 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 0.09 (0.00) |

0.06 (0.01) |

0.11 (0.00) |

0.07 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Primary Education | 0.39 (0.01) |

0.34 (0.01) |

0.41 (0.01) |

0.38 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Middle School | 0.31 (0.00) |

0.37 (0.01) |

0.29 (0.01) |

0.30 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| High School | 0.20 (0.00) |

0.22 (0.01) |

0.19 (0.01) |

0.25 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Child Annual Income | |||||

| Less than 5k | 0.11 (0.00) |

0.20 (0.01) |

0.10 (0.00) |

0.06 (0.00) |

0.00 |

| 5k–50k | 0.61 (0.01) |

0.64 (0.01) |

0.61 (0.01) |

0.58 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| 50k & above | 0.07 (0.00) |

0.05 (0.00) |

0.06 (0.00) |

0.12 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Missing | 0.22 (0.01) |

0.11 (0.01) |

0.23 (0.01) |

0.24 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Observations | 15418 | 2273 | 9999 | 3146 |

Notes:

Sample: adult children (aged 25 or above) from CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above).

Nearby child is defined as living outside of the household but within the same county.

Clustered standard errors at family level in brackets.

P-values of testing whether the means are equal are provided in the last column.

Table 3 also offers a detailed comparison between adult children living in the same household, those living within the same county and those who live far away from their parents. The co-resident adult children are generally younger than those who are non-co-resident. Parents are much more likely to live with sons. On average, co-resident adult children have more children (younger than 16 years old) than the non-co-resident adult children.

Table 4 shows the transfers provided by and to adult children differentiated according to living arrangements: living in the same county or far away.6 The probability of children transferring money to their parents is lower for those living in the same county, and the amount of gross transfers to parents is far higher for those adult children who live far away. The probability of receiving transfers from their parents is equally likely no matter how close the child lives. However, the closer child on average receives a larger amount from his or her parents, which may be used to pay for weddings and housing, although our data do not show this. In total, adult children transfer far more to parents than they receive. This is a different pattern than that observed in the USA or Europe, where net transfers are from elderly parents to adult children, but it is similar to the pattern observed in other low-income countries. As expected, children who live nearby are more likely to visit their parents or to have other communications with their parents, possibly for the purpose of providing help.7 On the other hand adult children who live farther away provide higher net transfers to their parents than do children who live nearby.

Table 4.

Contact and financial transfers by living arrangements of non-co-resident children.

| Overall | Live in the county |

Do not live in the county |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer to Parents | ||||

| Fraction Positive | 0.30 (0.01) |

0.28 (0.01) |

0.37 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Amount if > 0 (1000 RMB) | 2.41 (0.39) |

1.74 (0.19) |

4.01 (1.24) |

0.00 |

| Transfer from Parents | ||||

| Fraction Positive | 0.08 (0.00) |

0.08 (0.00) |

0.08 (0.01) |

0.00 |

| Amount if > 0 (1000 RMB) | 3.31 (0.51) |

3.53 (0.61) |

2.59 (0.81) |

0.00 |

| Net Transfer | ||||

| Average Amount (1000 RMB) | 1.41 (0.37) |

0.68 (0.22) |

3.23 (1.16) |

0.00 |

| Contact | ||||

| # of Visits per Year | 97.72 (1.60) |

123.27 (1.90) |

10.30 (0.97) |

0.00 |

| # of other Communications per Year* |

58.58 (1.38) |

63.27 (1.67) |

44.26 (1.67) |

0.00 |

| Observations | 13145 | 9999 | 3146 |

Note:

Sample: non-co-resident adult children from CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above).

Transfer amounts to parent and from parent are defined as the average amount conditional on the amount is positive.

Net transfer is defined as the amount of transfer from child to parents minus the amount of transfer the child received from parents.

Clustered standard errors at family level in brackets.

P-values of testing whether the means are equal are provided in the last column.

Other communications include email, mail, phone calls, text messages, etc.

To sum up the results in this section, we find that although more than half of the elderly CHARLS respondents live by themselves, most of them indeed have access to assistance from their children. The probability of the elderly living alone increases as they age, to a point, and then declines, but even as their living alone increases, it is mostly compensated by the presence of an adult child in the same village/community or county. Furthermore, children nearby pay more frequent visits to their elderly parents, while those further away are more likely to provide financial transfers and to provide a higher amount of net transfers on average.

4. The correlation between elderly living arrangements and contact and financial transfers between generations

In this section, we systematically examine the predictors of elderly living arrangements. The rich information on parent and child characteristics together allows us to group the data at the child level, that is, to treat each adult child as one observation. This enabled us to use both multinomial logit and family fixed-effects models, the fixed-effects models controlling for unobserved heterogeneity at the family level.8

We restricted our parent respondents to those who are aged 60 or above, with at least one child who is aged 25 or older and not a student. We found it was rarely the case that a parent and his or her spouse did not live together, so rather than treat them as two observations, we treat them as a single observation. Our sample includes 4697 respondents and correspondingly 15,418 observations in the child sample.

Below, we report the results from estimation on co-residence and on proximity, and then examine the associations of living arrangement with visit frequencies and transfers.

4.1. Correlates of living arrangements

A number of factors influence whether the elderly live with or close to their adult children. The usual predictors include the care needs of the elderly, the preferences of both parents and children and the resources of parents and their potential caregivers. In our model, we proxied the care needs of the parents using their widowhood and their self-reported general health and functional limitations. Parental and child preferences are represented by demographic characteristics. For children with both parents present, we used the maximum age of the parents, as we did for Table 2, because the age of the older parent may be what drives living arrangements. Other demographic factors may matter as well. For example, the marital status of a child may significantly affect the parent’s utility of living with the child due to in-law rivalry. On the other hand, parents (and children) may prefer living with children who have children themselves.

We controlled for parental resources by their level of education, the pre-transfer income of the household that the parents live in and by their ownership of housing. In the case of two-parent households, we used the maximum level of education of the two, which is presumably better associated with the ability of couples to earn income and to make decisions. We took household income rather than income of just the main respondent or spouse because for rural households that farm or households with non-farm family businesses it is very difficult to separately measure the income of only one person. Housing was included because it is an important asset, and children may care for parents by living together in anticipation of an inheritance.

We also need to control for the resources of the children, and for all the children, since children may substitute among themselves. For example a child with more education and the ability to earn a higher income by migrating may not live with the parent, but may send money transfers instead. The parent(s) then might live with a less educated child. A child with more male siblings may be less likely to live with their parent(s) because there are more male siblings who could do so.

We measured child resources by the level of education of the index child, and by the household income of that child. The children’s income was measured at the household level, not the child’s income. It was measured as an ordinal variable to reduce error because it is proxy reported by the parent. We created dummy variables indicating which ordinal income group the child is in. To record the resources of other children (if they exist), we took the maximum level of education of siblings and the maximum level of siblings’ household incomes (measured ordinally) and construct our dummy variables accordingly. We also controlled for the numbers of brothers and the number of sisters separately and for a quadratic in age of the index child and for the maximum age of a sibling. We added a dummy variable equal to one if the child has no siblings.9 In the case that a child had no siblings, we set the sibling variables to zero, equivalent to interacting the sibling variables with an indicator that the child does have siblings. To model living arrangements we took these sibling variables for all the siblings of the index child. However, when we modeled transfers of both time and money (or in-kind resources), we only used characteristics of siblings who are non-co-resident with the parent(s), since we only counted transfers by them. Finally, in the family fixed-effects specifications, the sibling characteristics do not difference out, because they are constructed for each child and may differ by child. As family fixed-effects models compare children within families; we drop in those specifications children with no siblings, or for transfers, with no non-co-resident siblings.

We adopted a multinomial logit model to analyze the multiple choices on living arrangements. We set those without any child living in the same county as the base group and examined the relative risk of co-residence and of having a child nearby (in the same county). Table 5 presents the results from the multinomial logit estimation, with relative risk coefficients reported in two sections, first on child characteristics and then on parent characteristics. From the first section of Table 5, we can see that sons are much more likely to live with their parents, and married children are unlikely to do so. Children with more young offspring are more likely to live with their elderly parents, although this association is not statistically significant. The higher the income of the children, the lower their likelihood of living with or proximate to their elderly parents, particularly at incomes above 50,000 RMB per year. Having more brothers is associated with a lower likelihood of living with one’s parents, although a higher probability of living in the same county (versus living in another county).We also see from the second section of Table 5 that parents’ maximum age, though not statistically significant, demonstrates a concave relationship with their living with a child. Urban residents are more likely to co-reside with or be proximate to their adult children. Parental education levels are not significantly related to living with or proximate to an adult child. There is a nonlinear, positive correlation between income and co-residence, but it is only significant among those elderly whose household income is above the median.10 Parents who own a house are much less likely to co-reside with their children. The parental health characteristics we examined (self-reported health and ADL/IADL difficulty) are uncorrelated with living decisions.

Table 5.

Multinomial estimation on living arrangements by children.

| In the same household | Within the county | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk | Z-score | Relative risk | Z-score | |

| Child Characteristics | ||||

| Child Age | 0.837*** | −7.395 | 1.097*** | 4.247 |

| Child Age^2/100 | 1.173*** | 6.301 | 0.936*** | −2.757 |

| Male Child | 7.530*** | 23.149 | 0.841*** | −3.459 |

| # of Grandchild under 16 | 1.092 | 1.490 | 0.938 | −1.556 |

| Married | 0.332*** | −9.729 | 2.046*** | 7.827 |

| Rural Hukou | 2.712*** | 7.785 | 1.795*** | 6.297 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary School | 0.914 | −0.523 | 0.842* | −1.737 |

| Middle School | 0.978 | −0.124 | 0.666*** | −3.725 |

| High School & Above | 0.723 | −1.642 | 0.501*** | −5.603 |

| P-value for Child Education | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Child Annual Income | ||||

| 5k–50k | 1.190* | 1.700 | 1.053 | 0.729 |

| 50k & above | 0.442*** | −4.498 | 0.429*** | −7.360 |

| P-value for Child Income | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Sibling Characteristics | ||||

| Have No Sibling | 0.560 | −1.352 | 0.439** | −2.276 |

| Max Sibling Age | 0.985** | −2.340 | 0.992 | −1.586 |

| # of Male Siblings | 0.551*** | −11.742 | 1.075** | 2.175 |

| # of Female Siblings | 0.955 | −1.254 | 1.039 | 1.299 |

| Max Sibling Annual Income | ||||

| 5k–50k | 0.867 | −0.893 | 0.824* | −1.660 |

| 50k & Above | 1.085 | 0.405 | 0.824 | −1.365 |

| P-value for Sibling Income | 0.145 | 0.145 | ||

| Max Sibling Education | ||||

| Primary School | 0.620 | −1.629 | 0.903 | −0.418 |

| Middle School | 0.677 | −1.317 | 1.029 | 0.118 |

| High School & Above | 0.685 | −1.241 | 1.006 | 0.022 |

| P-value for Sibling Education | 0.351 | 0.351 | ||

| Parent Characteristics | ||||

| Max Age | 0.956 | −0.563 | 1.107 | 1.592 |

| Max Age^2/100 | 1.054 | 0.962 | 0.938 | −1.466 |

| P-value for Age | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Single Man | 1.142 | 1.022 | 1.155 | 1.471 |

| Single Woman | 1.144 | 1.284 | 0.991 | −0.106 |

| Urban | 1.514*** | 3.330 | 1.334*** | 2.825 |

| Highest Education | ||||

| Primary Education | 0.919 | −0.820 | 0.890 | −1.454 |

| Middle School & Above | 1.010 | 0.069 | 1.008 | 0.077 |

| P-value for Education | 0.429 | 0.429 | ||

| Owning House | 0.145*** | −19.442 | 0.920 | −1.070 |

| Pre-transfer Income (1000 RMB) | ||||

| For PTI below Median | 1.090 | 0.567 | 1.002 | 0.153 |

| For PTI above Median | 1.018** | 2.308 | 1.015*** | 3.061 |

| P-value for Income | 0.012 | 0.012 | ||

| Poorest Health | ||||

| SRH Very Poor | 0.928 | −0.513 | 1.049 | 0.392 |

| Any ADL/IADL Difficulty | 0.849 | −1.266 | 0.924 | −0.762 |

| P-value for Health | 0.503 | 0.503 | ||

| Constant | 0.56 | 2.396 | 0.007** | −2.113 |

| County Dummy | Yes | Yes | ||

| P-value for County Dummies | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Observations | 15,418 | 15,418 | ||

Notes:

Sample: Adult children aged 25 and older from CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above).

Standard errors clustered at family level.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

The estimates in Table 5 may be confounded because of unobservable factors. In Table 6, we provide an alternative model of children living with their parents, a linear probability model, which controls for family fixed effects. This model allows us to examine more closely the influence of child characteristics on co-residence, while controlling for family-level unobservables. The sample is restricted to those children with at least one adult sibling. Results are similar to Table 5.11 Child income remains significant and retains a non-linear relationship. Other results are quite similar: sons are far more likely to live with their parents than daughters, married children less likely, children with a rural hukou,12 more likely. Having an older sibling is associated with a lower likelihood of living with one’s parents, as is having a sibling with some education (at nearly 5% significance). We also provide results from subsamples of the children divided according to their parents’ type of residence. The results are quite similar for parents living in urban versus rural areas. It is very rare to see an urban parent with a child of rural hukou, so the rural hukou coefficient for children with urban parent is not significant.

Table 6.

Child co-residence (family fixed effects).

| Total sample | Urban parent | Rural parent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Child Characteristics | ||||||

| Child Age | −0.028*** | (0.003) | −0.042*** | (0.006) | −0.021*** | (0.004) |

| Child Age^2/100 | 0.022*** | (0.003) | 0.033*** | (0.006) | 0.016*** | (0.004) |

| Male Child | 0.198*** | (0.007) | 0.172*** | (0.011) | 0.212*** | (0.008) |

| Married | −0.175*** | (0.015) | −0.138*** | (0.026) | −0.194*** | (0.019) |

| # of Grandchild <16 | 0.005 | (0.005) | 0.006 | (0.011) | 0.005 | (0.006) |

| Rural Hukou | 0.052*** | (0.011) | 0.006 | (0.020) | 0.077*** | (0.013) |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary School | −0.020* | (0.012) | −0.064** | (0.030) | −0.011 | (0.013) |

| Middle School | −0.020 | (0.014) | −0.043 | (0.032) | −0.021 | (0.016) |

| High School | −0.019 | (0.018) | −0.050 | (0.035) | −0.014 | (0.024) |

| P-value for Child Education | 0.395 | 0.127 | 0.647 | |||

| Child Annual Income (less than 5k as reference) | ||||||

| 5k–50k | −0.043** | (0.018) | −0.045 | (0.031) | −0.044** | (0.021) |

| 50k & Above | −0.070*** | (0.026) | −0.086** | (0.040) | −0.062* | (0.034) |

| P-value for Child Income | 0.015 | 0.098 | 0.086 | |||

| Sibling Characteristics | ||||||

| Max Sibling Age | −0.006*** | (0.002) | −0.010*** | (0.003) | −0.005** | (0.002) |

| Max Sibling Annual Income | ||||||

| 5k–50k | 0.047 | (0.031) | 0.050 | (0.054) | 0.051 | (0.038) |

| 50k & above | 0.075* | (0.041) | 0.094 | (0.065) | 0.062 | (0.053) |

| P-values for Sibling Income | 0.184 | 0.342 | 0.398 | |||

| Max Sibling Education | ||||||

| Primary School | −0.096** | (0.042) | −0.107 | (0.090) | −0.090* | (0.047) |

| Middle School | −0.116*** | (0.044) | −0.120 | (0.091) | −0.116** | (0.049) |

| High School & Above | −0.113** | (0.047) | −0.151 | (0.094) | −0.093* | (0.054) |

| P-values for Sibling Education | 0.065 | 0.387 | 0.094 | |||

| R-Square | 0.187 | 0.176 | 0.200 | |||

| Observations | 14866 | 5278 | 9588 | |||

Notes:

Sample: Adult children aged 25 and older from CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above), and who have at least one adult sibling.

Robust standard errors are reported.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

To examine responsibility sharing among sons of different birth order, we further restricted our sample to families with two or more sons, and divided male children into three groups, youngest son, oldest son and middle sons. From Appendix 1 we can see that both oldest son and youngest son (compared to middle sons) are more likely to co-reside with elderly parents, and the youngest son is more likely than the oldest son to live with their parents. It is likely that the oldest son moved out of the house first and has established himself, while the youngest son may still be living with his parents. This pattern has been observed elsewhere, for example in the United States during the 1900s (Tarver 1952, as cited by Easterlin 2004). Child income has a larger effect on children with urban parents.

The above findings are consistent with the existing literature (Logan, Bian, and Bian 1998; McGarry and Schoeni 2000; Meng and Luo 2008; Zimmer and Korinek 2008). We find that co-residence is largely dependent on elderly parents’ needs. Adult children with more children (grandchildren of the parents) are more likely to co-reside with their parents. However the resources of both children and parents play an important role as well; in general parents with more non-housing resources are more likely to live with their children, while children with higher levels of income are less likely to do so.

4.2. Living arrangements and contact and transfers between generations

In this section, we examine the associations between living arrangements and other forms of support for parents: the frequency of visits; other communications; and financial transfers. As transfers and contacts can only be defined clearly among non-co-resident children and their parents, we exclude co-resident children from this estimation.13 Again the proximity of a child is defined as living within the same county as his/her parents. The CHARLS survey asks how many times each non-co-resident child visits or communicates in other forms (call, mail, email, etc.) with elderly parents each year. Financial transfers are measured in three ways: (1) whether the child transfers money to his/her elderly parents; (2) whether the parents transfers money to the child; and (3) the net amount of transfers to parents, with positive values being from child to parent.

The covariates for the contact and financial transfer regressions include both parental and individual adult child characteristics. As seen from the first two pairs of columns in Table 7, the proximity to parents has strong positive effects on the probability of child visits and other communications, replicating the bivariate results in Table 4. Another factor worth noting is that, the more brothers a child has, the less likely he/she visits frequently or uses other forms of communications. Having more sisters is associated with making fewer non-visit communications. A male child is more likely to visit but gender is not correlated with the likelihood to call or contact with other communications. A higher adult child income increases the probabilities of visits and communications in a non-linear manner, and having high school or greater schooling is associated with more non-visit communications. A single male parent gets the least attention from children. Higher parental income is associated with an increase in visits and other communications, the association being non-linear and stronger for parents with incomes above the median.

Table 7.

Contact and financial transfers of non-co-resident children.

| Visits/year | Other communications/ year |

Transfer to parents | Transfer from parents |

Net amount of transfer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Live in the same county | 114.098*** | (2.302) | 23.848*** | (2.209) | −0.061*** | (0.013) | 0.021*** | (0.007) | −891.551** | (416.175) |

| Parents live with another adult child | −6.803 | (4.149) | −3.571 | (3.844) | −0.020 | (0.020) | −0.026** | (0.010) | −10.412 | (224.625) |

| Parent Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.584 | (3.291) | −2.756 | (2.771) | 0.006 | (0.015) | −0.019*** | (0.007) | 125.771 | (126.174) |

| Age^2/100 | −1.057 | (2.230) | 1.875 | (1.888) | −0.006 | (0.010) | 0.011** | (0.005) | −95.479 | (90.348) |

| Single Man | −17.231*** | (4.994) | 19.873*** | (3.963) | −0.021 | (0.024) | −0.027** | (0.011) | 1,107.964 | (1,125.476) |

| Single Woman | −0.679 | (4.073) | −1.180 | (3.546) | 0.015 | (0.020) | −0.010 | (0.010) | −274.937 | (276.225) |

| Urban | 32.639*** | (3.707) | 17.594*** | (3.299) | −0.059*** | (0.017) | −0.021** | (0.008) | 306.201** | (137.540) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Primary | 3.677 | (3.876) | 8.247*** | (3.176) | 0.014 | (0.019) | 0.019** | (0.009) | −422.719 | (489.284) |

| Middle School | 3.390 | (5.243) | 21.515*** | (4.470) | −0.007 | (0.025) | 0.034** | (0.013) | −311.176 | (573.908) |

| P-value for Education | 0.636 | 0.000 | 0.472 | 0.022 | 0.528 | |||||

| House Ownership | −4.209 | (4.516) | 9.945*** | (3.848) | −0.019 | (0.022) | −0.012 | (0.011) | 27.297 | (274.610) |

| Pre-transfer Income (1000 RMB) | ||||||||||

| For PTI Below Median | −1.003 | (0.639) | −0.693 | (0.943) | −0.004 | (0.004) | 0.002 | (0.002) | −352.918*** | (126.733) |

| For PTI Above Median | 0.433** | (0.193) | 0.967*** | (0.197) | −0.003*** | (0.001) | 0.002*** | (0.001) | −52.190** | (22.129) |

| P-value for Income | 0.037 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.001 | |||||

| Health | ||||||||||

| Worse SRH Very Poor | −10.511* | (5.432) | −0.112 | (4.590) | −0.054** | (0.027) | −0.008 | (0.014) | −335.572 | (204.116) |

| Any ADL/IADL Difficulty | −6.294 | (4.797) | −2.372 | (3.995) | −0.032 | (0.022) | −0.008 | (0.011) | −112.829 | (152.474) |

| P-value for Health | 0.007 | 0.805 | 0.005 | 0.406 | 0.152 | |||||

| Child Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Child Age | 1.853 | (1.157) | −1.613 | (1.157) | −0.005 | (0.004) | 0.004** | (0.002) | −25.567 | (43.530) |

| Child Age^2/100 | −1.526 | (1.282) | 1.310 | (1.273) | 0.002 | (0.004) | −0.006** | (0.002) | 42.327 | (37.307) |

| Male Child | 73.960*** | (2.719) | −0.826 | (1.999) | −0.031*** | (0.009) | 0.038*** | (0.005) | 125.261 | (206.391) |

| Married | 1.269 | (2.058) | −0.706 | (1.482) | 0.025*** | (0.008) | 0.002 | (0.003) | −96.070 | (207.063) |

| # of Grandchild <16 | −3.432 | (2.738) | −0.985 | (1.982) | −0.009 | (0.010) | 0.004 | (0.005) | −213.264 | (285.690) |

| Child Rural Hukou | 3.885 | (5.314) | 9.287*** | (3.532) | 0.087*** | (0.016) | 0.023** | (0.009) | 317.131* | (173.584) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Primary Education | 1.987 | (4.463) | −3.110 | (3.059) | 0.058*** | (0.017) | 0.003 | (0.007) | 418.771* | (226.744) |

| Middle School | 1.384 | (4.965) | 3.470 | (3.508) | 0.074*** | (0.018) | 0.000 | (0.008) | 623.690* | (348.402) |

| High School & Above | −0.213 | (5.709) | 17.319*** | (4.424) | 0.099*** | (0.020) | 0.016 | (0.010) | 1,237.654 | (968.767) |

| P-value for Child Education | 0.934 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.287 | 0.235 | |||||

| Child Annual Income | ||||||||||

| 5k–50k | 8.221** | (3.609) | 6.462** | (2.583) | 0.053*** | (0.012) | 0.012* | (0.006) | 1.460 | (158.086) |

| Above 50k | −1.709 | (5.607) | 13.103*** | (4.643) | 0.133*** | (0.020) | 0.027** | (0.013) | 2,859.261** | (1,382.087) |

| P-value for Child Income | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.088 | |||||

| Sibling Characteristics (Non-Resident) | ||||||||||

| Have No Sibling | 5.593 | (14.848) | −1.415 | (13.138) | −0.117* | (0.061) | 0.028 | (0.032) | −784.222 | (727.239) |

| Max Sibling Age | 0.016 | (0.258) | −0.362 | (0.245) | −0.003*** | (0.001) | −0.001 | (0.001) | −12.836 | (10.477) |

| # of Male Siblings | −4.304*** | (1.619) | −2.717* | (1.445) | 0.013 | (0.008) | −0.005 | (0.004) | 9.344 | (79.374) |

| # of Female Siblings | −0.864 | (1.533) | −2.791** | (1.209) | 0.031*** | (0.007) | −0.010*** | (0.003) | 279.825 | (210.328) |

| Max Sibling Annual Income | ||||||||||

| 5k–50k | −10.846* | (6.451) | −0.442 | (4.870) | 0.043* | (0.023) | 0.010 | (0.009) | −153.904 | (235.493) |

| 50k & Above | −11.855 | (7.532) | 5.489 | (6.093) | 0.099*** | (0.030) | 0.056*** | (0.015) | 846.448* | (489.027) |

| P-value for Sibling Income | 0.226 | 0.325 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.135 | |||||

| Max Sibling Education | ||||||||||

| Primary School | −1.759 | (9.034) | −5.679 | (6.319) | −0.018 | (0.035) | −0.012 | (0.014) | −42.954 | (237.318) |

| Middle School | −4.604 | (9.085) | −4.300 | (6.456) | −0.028 | (0.036) | 0.000 | (0.014) | −181.726 | (221.907) |

| High School & Above | 1.607 | (9.483) | −3.875 | (6.780) | −0.023 | (0.037) | 0.007 | (0.015) | 269.812 | (357.856) |

| P-value for Sibling Education | 0.387 | 0.783 | 0.835 | 0.110 | 0.184 | |||||

| Constant | 144.320 | (114.822) | 186.819* | (96.041) | 0.367 | (0.537) | 0.747*** | (0.257) | −2,997.276 | (4,780.627) |

| County Dummy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Observations | 12,523 | 12,099 | 13,145 | 13,145 | 13,145 | |||||

| R-Squared | 0.189 | 0.124 | 0.070 | 0.058 | 0.020 | |||||

Notes:

Sample: non-co-resident adult children from CHARLS elderly households (with at least one respondent 60 or above).

Clustered standard errors at family level are reported.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

The third, fourth and fifth pairs of columns in Table 7 report estimates on whether an adult child provides a transfer to his/her parents, receives a transfer and the net amount of transfers to their parents respectively. The frequency of child transfers to parents and the net amount transferred are negatively related to proximity. Hence, though children living far away visit less often, they are more likely to transfer money to their parents and send a greater amount when they make transfers. For transfers from parents, however, the association is the opposite: children who live closer are more likely to receive a transfer from their parents. If an elderly parent co-resides with an adult child, another non-co-resident child is less likely to provide help to parents, but the differences are generally not significant. A child with more sisters is associated with that child being more likely to make a transfer to his or her parents, but he or she is less likely to receive a transfer from his or her parents. The higher the education a child has, the more he/she provides to the elderly parents (though not at a statistically significant level) and the greater the amount transferred. The same result applies to children with higher income levels, particularly incomes above 50,000 RMB per year. Interestingly, children with higher incomes are also more likely to receive transfers from their parents. There is an obvious nonlinear effect of parental pre-transfer income. A child is slightly less likely to transfer money to his/her parents if parental income is higher, but this is only true if parental income is greater than the sample median. Parents with higher pre-transfer incomes receive fewer transfers, the relationship being nonlinear with a larger association for those with pre-transfer incomes below the median.14 For transfers from parents to children, parents with higher incomes are more likely to make such transfers, but again only for parents with pre-transfer incomes above the median. However, the net amount of transfers from children to parents has a much larger negative gradient among parents with incomes below the median. Interestingly, having a sibling with a higher income is associated with a greater chance of making a transfer to the parents and for a larger amount. Yet the sibling with the higher income is also more likely to receive a transfer from the parents. As we will see, some of these signs change or the magnitudes become insignificant once we control for family fixed effects; so it must be that on average, families whose children collectively make more income are more likely to make transfers to parents and in larger amounts.

We also use a family fixed-effects model to estimate the substitution effects between living arrangements and other kinds of transfer. We can see from Table 8, in families with two or more children, the results are largely the same as in Table 7 even if we control for family heterogeneity. However, the associations between the size of net transfers and child schooling and income are no longer significant, although they show an increase in the probability of making a transfer. Now we can see that, holding total family resources constant, having a sibling with more income is negatively, not positively, associated with making a transfer to one’s parents. Sibling incomes are no longer statistically significant in affecting transfers received, or the net amount of transfers made. Having siblings with higher incomes is, however, positively associated with making visits to parents.

Table 8.

Contact and financial transfers of non-co-resident children (family fixed effects).

| Visits/year | Other communications/year | Transfer to parents | Transfer from parents | Net amount of transfer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Child living in the same county | 106.931*** | (3.539) | 20.311*** | (2.491) | −0.029*** | (0.008) | 0.012** | (0.005) | −1,262.909 | (781.757) |

| Child Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Child Age | 0.499 | (1.393) | −0.980 | (0.743) | −0.002 | (0.002) | 0.004*** | (0.002) | −44.969 | (58.053) |

| Child Age^2/100 | 0.223 | (1.588) | 1.081 | (0.824) | 0.002 | (0.002) | −0.005*** | (0.002) | 137.992* | (79.045) |

| Male | 77.280*** | (3.080) | −0.244 | (1.875) | −0.009 | (0.006) | 0.032*** | (0.004) | 280.749* | (165.059) |

| Rural Hukou | 38.476*** | (5.394) | 4.887 | (3.286) | −0.025** | (0.011) | 0.009 | (0.006) | 737.739 | (901.368) |

| Married | 3.388 | (6.543) | 2.269 | (3.431) | 0.067*** | (0.013) | 0.018** | (0.008) | −300.405 | (442.367) |

| # Grandchild Under 16 | 4.987** | (2.319) | 0.725 | (1.327) | 0.000 | (0.004) | 0.002 | (0.003) | −306.540 | (210.311) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Primary School | 4.372 | (5.994) | −2.306 | (3.176) | 0.011 | (0.013) | −0.008 | (0.007) | 1,776.762 | (1,542.314) |

| Middle School | 1.277 | (7.301) | 7.447* | (4.059) | 0.030** | (0.014) | −0.011 | (0.009) | 2,356.415 | (2,030.450) |

| High School and Above | −3.493 | (9.498) | 10.417* | (5.672) | 0.043** | (0.020) | −0.006 | (0.011) | 4,496.983 | (3,934.934) |

| P-value for Child Education | 0.696 | 0.001 | 0.055 | 0.589 | 0.709 | |||||

| Child Annual Income | ||||||||||

| 5k–50k | 8.090 | (6.110) | 9.034*** | (3.321) | 0.025** | (0.010) | 0.009 | (0.008) | 1,759.146 | (1,367.803) |

| 50k & Above | 8.902 | (11.273) | 12.384* | (7.397) | 0.055** | (0.023) | 0.004 | (0.015) | 7,706.371 | (6,659.270) |

| P-value for Child Income | 0.403 | 0.020 | 0.022 | 0.514 | 0.331 | |||||

| Sibling Characteristics (Non-Resident) | ||||||||||

| Max Sibling Age | 0.922 | (0.704) | 0.161 | (0.404) | 0.001 | (0.001) | −0.002** | (0.001) | 100.301 | (90.512) |

| Max Sibling Annual Income | ||||||||||

| 5k–50k | 25.436** | (12.765) | 7.673 | (7.411) | −0.050** | (0.024) | −0.009 | (0.015) | 1,387.300 | (1,526.213) |

| 50k & Above | 43.409** | (17.571) | 11.704 | (11.019) | −0.112*** | (0.037) | 0.006 | (0.023) | 7,013.869 | (6,860.278) |

| P-values for Sibling Income | 0.044 | 0.515 | 0.011 | 0.636 | 0.592 | |||||

| Max Sibling Education | ||||||||||

| Primary School | −15.734 | (15.369) | −18.884** | (9.180) | −0.031 | (0.027) | −0.031* | (0.017) | 1,254.678 | (1,563.642) |

| Middle School | −20.265 | (15.951) | −12.499 | (9.849) | −0.021 | (0.029) | −0.029 | (0.019) | 1,881.891 | (2,157.972) |

| High School & Above | −12.495 | (17.902) | −18.346 | (11.199) | −0.040 | (0.034) | −0.019 | (0.022) | 4,049.557 | (4,122.471) |

| P-values for Sibling Education | 0.517 | 0.075 | 0.484 | 0.237 | 0.701 | |||||

| Observations | 11856 | 11457 | 12451 | 12451 | 12451 | |||||

| R-Squared | 0.179 | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.017 | 0.025 | |||||

Notes:

Sample includes non-co-resident adult children of 25 and older who have at least one parent no younger than 60 and who have at least one adult sibling.

Robust standard errors are reported.

***p < 0.01; **p <0.05; *p < 0.1.

5. Conclusions

Previous literature has provided evidence that the Chinese elderly are increasingly more likely to live alone or with only a spouse. This has raised concerns regarding support for the elderly, considering the current lack of a strong public social security system in China. Using a nationally representative sample, this article adds to the growing literature that living close to parents has become an important way of providing elderly support while at the same time maintaining the independence/privacy of both parents and their adult children. We conclude from the results that noting that the elderly tend to live alone is inadequate to describe their living arrangements.

We also find the existence of responsibility sharing among siblings and the different types of intergenerational transfers, financial and non-financial, play a supplementary role in the unequal distribution of living arrangements. Adult children who live close to their parents visit them more frequently, providing nonfinancial transfers, while those living far away provide a larger amount of financial transfers.

Investigating the determinants of elderly living arrangements and transfers, we find evidence that parents with higher pre-transfer incomes are more likely to live with or near their adult children, but they tend to receive smaller amounts of financial transfers from their children. This indicates that while financial transfers may be motivated by the altruistic concern of children for their parents, the reasons for living arrangement may include other objectives, such as sharing housing or other benefits from parents.

Estimating a family fixed-effects model, we find that adult sons, and particularly youngest sons, are more likely to live with their elderly parents, an unexpected result that differs from the tradition of parents depending mainly on their eldest sons. Further research is needed to explore the underlying driving force of this transition. Adult daughters, as expected, are less likely to live with their parents, but this effect is weaker among children with an urban parent.

One very important set of findings has to do with the correlations between the number and characteristics of siblings. Having a parent live with one child reduces the burden on the other children in terms of visiting and their likelihood of making a financial transfer. Having siblings with higher incomes reduces the chance that a child will make financial transfers to their parents. It is also the case that our results show that investing in educating their children more does have a payoff in terms of being more likely to receive a financial transfer when the parent is older. As noted, it is the case that the older cohorts in this sample have on average 3.3 children because they were not subject to the One Child Policy during most of their childbearing years, although they were partially exposed to the increasingly strong family planning policies of the 1970s. The average parent in our sample would have been born in 1942, so they would have been in their very late 20s and early 30s even during the family programs established during the early 1970s. It may be that cohorts younger than the ones studied here, who were exposed to the stronger family planning programs during their childbearing ages will be more constrained in their living arrangements than these cohorts, which remains for future study. On the other hand, if they have invested more in their children’s schooling those constraints may be offset by financial transfers.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate helpful comments from Jorge Bravo, Richard Easterlin, Mark Rosenzweig and Zachary Zimmer and participants at the Development Economics Seminar, Yale University.

Funding

This research was supported by the BSR division of the National Institute on Aging [grant number 1R01AG037031], [grant number R03AG049144]; the Management Science Division of the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 71130002], [grant number 71450001]; China Medical Board and Peking University.

Appendix 1

Child co-residence for families with at least two sons (family fixed effects)

| Total sample | Urban parent | Rural parent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | Coef. | S.E. | |

| Child Characteristics | ||||||

| Child Age | −0.018*** | (0.003) | −0.034*** | (0.006) | −0.011** | (0.004) |

| Child Age^2/100 | 0.015*** | (0.003) | 0.027*** | (0.006) | 0.008* | (0.005) |

| Sons (Middle Sons as Reference) | ||||||

| Oldest Son | 0.028** | (0.011) | 0.048** | (0.020) | 0.018 | (0.014) |

| Youngest Son | 0.097*** | (0.012) | 0.109*** | (0.021) | 0.091*** | (0.015) |

| Daughter | −0.076*** | (0.010) | −0.033** | (0.017) | −0.095*** | (0.012) |

| Married | −0.190*** | (0.018) | −0.143*** | (0.031) | −0.211*** | (0.022) |

| # of Grandchild <16 | 0.006 | (0.006) | 0.010 | (0.014) | 0.006 | (0.007) |

| Rural Hukou | 0.064*** | (0.012) | 0.020 | (0.022) | 0.087*** | (0.013) |

| Education | ||||||

| Primary School | 0.005 | (0.013) | −0.025 | (0.033) | 0.009 | (0.015) |

| Middle School | 0.011 | (0.016) | 0.003 | (0.037) | 0.005 | (0.018) |

| High School | 0.016 | (0.021) | −0.001 | (0.039) | 0.016 | (0.027) |

| P-value for Child Education | 0.855 | 0.475 | 0.889 | |||

| Child Annual Income | ||||||

| 5k–50k | −0.032 | (0.020) | −0.033 | (0.036) | −0.032 | (0.024) |

| 50k & above | −0.063** | (0.030) | −0.070 | (0.049) | −0.064* | (0.037) |

| P-value for Child Income | 0.096 | 0.360 | 0.207 | |||

| Sibling Characteristics | ||||||

| Max Sibling Age | −0.004 | (0.002) | −0.009* | (0.005) | −0.002 | (0.003) |

| Max Sibling Annual Income | ||||||

| 5k–50k | 0.052 | (0.040) | 0.078 | (0.070) | 0.045 | (0.049) |

| 50k & Above | 0.063 | (0.051) | 0.154* | (0.082) | 0.012 | (0.065) |

| P-values for Sibling Income | 0.400 | 0.150 | 0.491 | |||

| Max Sibling Education | ||||||

| Primary School | −0.083 | (0.064) | −0.022 | (0.094) | −0.096 | (0.073) |

| Middle School | −0.096 | (0.065) | −0.041 | (0.093) | −0.112 | (0.074) |

| High School & Above | −0.073 | (0.067) | −0.020 | (0.096) | −0.085 | (0.079) |

| P-values for Sibling Education | 0.379 | 0.919 | 0.402 | |||

| R-Square | 0.158 | 0.167 | 0.163 | |||

| Observations | 9812 | 3128 | 6684 | |||

Notes:

Sample includes adult children aged 25 and older who have at least one parent no younger than 60 in families with at least two sons.

Robust standard errors are reported.

***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

Footnotes

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the Population Association of America Annual Meetings, 2012, and at the World Congress of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, 2013.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

The counties represent all Chinese provinces except Hainan, Ningxia, which had no counties sampled, and Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, which were not included in the sample.

All numbers in Table 1 use sample weights that also adjust for individual and household non-response. See Zhao et al. (2013) for a discussion of sample weights.

We exclude a small number of individuals who are rotating parents because the living arrangements of such individuals are hard to define. Later in the article, in order to focus on living arrangement of elderly parents and their adult children, we further restrict the sample to those elderly with at least a child of 25 or older and not currently in school. However for Table 1 we do not restrict the sample by age of children of the elderly.

For this table and the rest of the article, we restrict our attention to elderly households with at least one respondent 60 and older. We also exclude a small number of households with respondents who are separated couples, or are rotating parents because the living arrangements of such households are hard to define. Further, in order to focus on living arrangement of elderly parents and their adult children, we further restrict to those with at least one child 25 or older who is not currently in school.

We treat living in the same county as living nearby because the distance within a county allows for daily communications.

Though these education levels are considerably higher than those of the respondent’s parents.

Transfer data are only collected for non-co-resident children because it is very hard conceptually to measure transfers within the household.

Other communications include email, mail, phone calls, text messages and so forth.

Standard errors are clustered at the family level to adjust the biases in standard errors due to the correlations within families.

There are also some missing variable dummies that we do not report, for example for age of siblings.

We model pre-transfer income as a linear spline with knot point at the median. The coefficient on the segment above the median is the slope (not the change in slope) over that segment. We also exclude those public transfers endogenous to number of children from the calculation of income.

We drop the number of brothers and number of sisters because they are so collinear with the family fixed effects.

A hukou is a record in the system if household registration required by law in China, which officially identifies a person as a resident of an area.

CHARLS, like most surveys, only collects contact and transfer data on non-co-resident family members.

Cai, Giles, and Meng (2006), using an urban survey from China, also find fewer transfers as parental income rises, and also find a concave relationship, stronger for lower income parents.

References

- Agree EM. PhD diss. Duke University; 1993. Effects of Demographic Change on the Living Arrangements of the Elderly in Brazil: 1960–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Arokiasamy P, Bloom D, Lee J, Sekher TV, Mohanty SK. An Investigation of the Health, Social and Economic Well-Being of India’s Growing Elderly Population: Longitudinal Aging Study in India, Pilot Survey. International Institute of Population Studies, Harvard School of Public Health and RAND Corporation; 2013. http://iipsindia.org/pdf/LASI_brochure.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin D, Brandt L, Rozelle S. Aging, Wellbeing, and Social Security in Rural Northern China. Population and Development Review. 2000;26:89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bian F, Logan JR, Bian Y. Intergenerational Relations in Urban China: Proximity, Contact, and Help to Parents. Demography. 1998;35:115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai F, Giles J, Meng X. How Well Do Children Insure Parents against Low Retirement Income? An Analysis Using Data from Urban China. Journal of Public Economics. 2006;90:2229–2255. [Google Scholar]

- CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study) China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study 2011–2012 National Baseline. Beijing: Peking University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- CHARLS Research Team. Challenges of Population Aging in China: Evidence from the National Baseline Survey of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Beijing: School of National Development, Peking University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Costa DL. National Bureau of Economic Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. Displacing the Family. [Google Scholar]

- Doty P. Family Care of the Elderly: The Role of Public Policy. The Milbank Quarterly. 1986;64:34–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin R. The Reluctant Economist: Perspectives on Economics, Economic History and Demography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt GV, Gruber J. Social Security and the Evolution of Elderly Poverty. NBER Working Paper Series. 2004;10466 [Google Scholar]

- Giles J, Mu R. Elderly Parent Health and the Migration Decisions of Adult Children: Evidence from Rural China. Demography. 2007;44:265–288. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Russell D. Identifying Living Arrangements that Heighten Risk for Loneliness in Later Life Evidence from the US National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2011;30(4):524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Kharicha K, Iliffe S, Illiffe S, Harari S, Swift C, Gillmann G, Stuck A. Health Risk Appraisal in Older People 1: Are Older People Living Alone an “At-Risk” Group? The British Journal of General Practice. 2007;57:271–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlikoff LJ, Morris JN. “Why Don”t the Elderly Live with Their Children? A New Look. NBER Working Paper Series. 1990;2734 [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Bian F, Bian Y. Tradition and Change in the Urban Chinese Family: The Case of Living Arrangements. Social Forces. 1998;76:851–882. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LG. Living Arrangements of the Elderly in Fiji, Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Demography. 1989;26:627–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K, Schoeni RF. “Social Security, Economic Growth, and the Rise in Elderly Widows” Independence in the Twentieth Century. Demography. 2000;37:221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Luo C. What Determines Living Arrangements of the Elderly in URBAN CHINA. In: Gustafsson BA, Li S, Sicular T, editors. Inequality and Public Policy in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 267–286. [Google Scholar]

- Mutchier JE, Burr JA. A Longitudinal Analysis of Household and Nonhousehold Living Arrangements in Later Life. Demography. 1991;28:375–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer E, Deng Q. What Has Economic Transition Meant for the Well-Being of the Elderly in China. In: Gustafsson BA, Li S, Sicular T, editors. Inequality and Public Policy in Urban China. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 182–202. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders P, Smeeding TM. How Do the Elderly in Taiwan Fare Cross-Nationally? Evidence from the Luxembourg Income Study Project. SPRC Discussion Paper No. 81. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Cong Z, Li S. Intergenerational Transfers and Living Arrangements of Older People in Rural China: Consequences for Psychological Well-Being. Journals of Gerontology, Series B. 2006;61(5):S256–S266. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.s256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R. Old Age Support in Contemporary Urban China from Both Parents’ and Children’s Perspectives. Research on Aging. 2002;24(3):337–359. [Google Scholar]

- Tarver J. Intra-Family Farm Succession Practices. Rural Sociology. 1952;17:266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassini C, Glaser K, Wolf DA, Broese van Groenou MI, Grundy E. Living Arrangements among Older People: An Overview of Trends in Europe and the USA. Population Trends. 2004;115:24–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing, 1950–2050. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Living Arrangements: Patterns and Trends. 2005 http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/livingarrangement/chapter2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Ageing: Profiles of Ageing. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, Bowling A. Being Alone in Later Life: Loneliness, Social Isolation and Living Alone. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2000;10:407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. Historical Evolution of Assisted Living in the United States, 1979 to the Present. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(Supplement):8–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.supplement_1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Wang Z. Dynamics of Family and Elderly Living Arrangements in China: New Lessons Learned from the 2000 Census. China Review. 2003;3:95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang G, Strauss J, Giles J, Hu P, Hu Y, Lei X, Park A, Smith JP, Wang Y. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study 2011–12 National Baseline User”s Guide. Beijing: China Center for Economic Research, Peking University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z, Korinek K. Does Family Size Predict Whether an Older Adult Lives with or Proximate to an Adult Child in the Asia-Pacific Region? Asian Population Studies. 2008;4(2):135–159. [Google Scholar]