Abstract

African American adolescents are exposed disproportionately to community violence, increasing their risk for emotional and behavioral symptoms that can detract from learning and undermine academic outcomes. The present study examined whether aggressive behavior and depressive and anxious symptoms mediated the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning, and if the indirect effects of community violence on academic functioning differed for boys and girls, in a community sample of urban African American adolescents (N = 491; 46.6% female). Structural equation modeling was used to examine the indirect effect of exposure to community violence in grade 6 on grade 8 academic functioning. Results revealed that aggression in grade 7 mediated the association between grade 6 exposure to community violence and grade 8 academic functioning. There were no indirect effects through depressive and anxious symptoms, and gender did not moderate the indirect effect. Findings highlight the importance of targeting aggressive behavior for youth exposed to community violence to not only improve their behavioral adjustment but also their academic functioning. Implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: community violence exposure, academic functioning, aggressive behavior

Introduction

Urban, particularly low-income, African American youth disproportionately reside in neighborhoods characterized by poverty, crime, and violence (Carlo, Crockett, Carranza, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010), increasing their risk for exposure to community violence as witnesses and victims (CDC, 2010). In fact, considerable research indicates that African American adolescents living in urban neighborhoods are exposed to community violence at higher rates than their Caucasian peers (e.g., Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006; Cooley, Turner, & Beidel, 1995; Gibson, Morris, & Beaver, 2009; Selner-O’Hagan, Kindlon, Buka, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1998). For example, African American youth living in high poverty neighborhoods witness community violence at higher rates than Caucasian youth (Gibson et al., 2009), and rates of victimization by serious violent crimes such as homicide, rape, and aggravated assault, are twice as high for African Americans than for their Caucasian counterparts (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006). Furthermore, African American adolescents and young adults are six times more likely to be victims of homicides than Caucasians (Aguirre, Turner, & Aguirre, 2008; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006). Thus, exposure to community violence is a significant concern for many urban African American adolescents.

The differences in the neighborhoods of residence and exposure to community violence between low-income urban African American adolescents and their Caucasian peers parallel race differences in academic outcomes for these groups of youth. Compared to their Caucasian counterparts, African American students generally underperform in vocabulary, reading, and math (NCES, 2000), and are less likely to complete high school (Chapman, Laird, Ifill, & KewalRamani, 2011). Exposure to crime and violence has been highlighted as a primary reason that disadvantaged neighborhoods have adverse effects on adolescents’ academic development (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). It has been suggested that youth exposed to high rates of crime and violence may expect to live shorter lives, and have few achievement related expectations due to a sense of foreshortened future (Cauce, Cruz, Corona, & Conger, 2011; Fitzpatrick, 1993; Meyers & Miller, 2004). As a result, community violence seems particularly relevant for understanding racial differences in academic functioning.

Several studies highlight the adverse effects of adolescents’ exposure to community violence experience on their academic development. Exposure to community violence has been linked with lower grade point average (Bowen & Bowen, 1999; Hurt, Malmud, Brodsky, & Gianetta, 2001; Overstreet & Braun, 1999; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003), standardized test scores in reading and math (Overstreet & Braun, 1999; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003), and school attendance (Bowen & Bowen, 1999) in cross-sectional research. In addition, Henrich and colleagues (2004) found that witnessing community violence was associated with lower standardized test scores in reading, writing, and math two years later (Henrich, Schwab-Stone, Fanti, Jones, & Ruchkin, 2004). While the available evidence documents associations between exposure to community violence and academic achievement, however, less is known about reasons for the association.

Psychological Symptoms as Mechanisms

African American adolescents’ exposure to community violence can lead to a range of symptoms and problems that detract from learning and lead to decreased academic functioning. For example, compared to youth who have not experienced community violence, youth exposed to community violence tend to report more problems with aggression, depression, and anxiety (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003, Richards et al., 2004); each predicts poorer academic functioning (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Guerra, Huesmann & Spindler, 2003; Richards et al., 2004, Masten, 2005). Thus, it is possible that exposure to community violence is associated with low academic functioning because its negative emotional and behavioral consequences make it difficult to perform well academically.

Aggression

A considerable body of research shows that adolescents’ exposure to community violence is linked to aggression (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Halliday-Boykins & Graham, 2001; Purugganan, Stein, Silver, & Benenson, 2003) and related behaviors, including retaliatory beliefs (McMahon, Felix, Halert, & Petropoulos, 2009), delinquency (Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, Ng-Mak, 2003) and violent behavior (Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004). In fact, associations between community violence and aggressive and violent behaviors are stronger than other outcomes (for reviews see Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura, & Baltes, 2009; Margolin & Gordis, 2000). Guerra and colleagues (2003) found that elementary and middle school students who witnessed community violence were more likely to imitate violence and aggressive behaviors than students who did not witness community violence (Guerra et al., 2003). Likewise, researchers found that youth who witnessed community violence exhibited aggressive behavior one year later (Ozer, 2005) and antisocial behavior two years later (Schwab-Stone et al., 1999). Of concern, adolescents’ aggressive behavior is associated negatively with their academic achievement (for a review see Wilson, Stover, & Berkowitz, 2009). For example, numerous studies have found an association between adolescents’ classroom aggression and their academic achievement (e.g., Basch, 2011; Miles & Stipeck, 2006). Youth who are aggressive may spend more time fighting, arguing, being disciplined (e.g., in school detentions, suspensions), or avoiding school, and therefore less time attending to academic work and learning (Basch, 2011). Relatedly, research examining the link between aggression and school engagement showed adolescents’ aggression directly affected their academic engagement and ability to learn (Hinshaw & Anderson, 1996; Miles & Stipeck, 2006).

Depression

The association between exposure to community violence and depression is less consistent than that with aggression (for a review see Fowler et al., 2009). Depressive symptoms identified in community violence exposed youth include intrusive thoughts and feelings, difficulties with concentration, hopelessness, and lack of belongingness (Osofsky, 1995; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003), and the association between exposure to community violence and depressive symptoms is found in cross sectional (Durant, Getts, Cadenhead, & Emans, 1995; Howard, Feigelman, Li, Cross, & Rachuba, 2002; McGee, 2003) and longitudinal research (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Rosenthal & Wilson, 2003). Moreover, Zinzow and colleagues found that witnessing community violence was associated with major depressive episodes in a national sample of adolescents (Zinzow et al., 2009). A number of studies have demonstrated that depressive symptoms can impair adolescents’ ability to function well academically (e.g., Da Fonseca at al., 2008; Fröjd et al., 2008; Hysenbegasi, Hass, & Rowland, 2005). For example, characteristics of depression such as impaired ability to concentrate, loss of interest, poor initiative, social withdrawal, and self-criticism affect cognitive performance and can diminish motivation to learn and overall academic achievement (Latzman & Swisher, 2005). In fact, previous studies have found associations between depression and low grade point average among middle and high school students (Fröjd et al., 2008; Puig-Antich et al., 1993; Reinherz, Frost, & Pakiz, 1991), even after one-year follow up (Shahar et al., 2006).

Anxiety

Exposure to community violence has been linked to anxious symptoms (Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz, & Walsh 2001; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Rosenthal, 2000), and there is evidence that these symptoms persist long term (Hammack, , Richards, Luo, Edlynn, & Roy, 2004; Ozer, 2005; Ruchkin, Henrich, Jones, Vermeiren, & Schwab-Stone, 2007). Post-traumatic stress symptoms, such as physiological arousal due to hyperactivation and constant threat management (LeDoux, 1992) are common for adolescents living in the midst of community violence (Perry, 1997), and several studies have found associations between exposure to community violence and post-traumatic stress symptoms and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD; Mazza & Reynolds, 1999; McCart et al., 2007; Ozer & Weinstein, 2004). Adolescents’ anxious symptoms can negatively impact their academic performance (Mazzone et al., 2007; McDonald, 2001; Wood, 2006), but few examined this empirically. Ialongo and colleagues (1994) found that first-grade children with high anxiety in the fall were eight times more likely to be in the lowest quartile for reading achievement and two and a half times more likely to be in the lowest quartile for math achievement the following spring (Ialongo, Edelsohn, Werthamer-Larsson, Crockett, & Kellam, 1994). Similarly, adolescents with severe anxious symptoms have a significantly greater likelihood of receiving failing grades (Stein & Kean, 2000) and anxiety can distract students from their learning and overall academic achievement (Parks-Stamm, Heilman, & Hearns, 2008). For example, Wood (2006) found that elevated anxiety produces a physiological arousal that narrows adolescents’ attention and impairs their ability to concentrate on other non-threatening stimuli, such as academics. Thus, anxious symptoms may compromise the adolescents’ academic performance.

Evidence of Psychological Symptoms as Mechanisms

The few studies focusing on the role of aggressive behaviors and depressive and anxious symptoms in the link between exposure to community violence and academic functioning primarily have been cross-sectional studies. Schwartz and Gorman (2003) found that witnessing community violence was associated with urban children’s symptoms of depression and disruptive behavior, which in turn were linked to poor academic achievement. In another cross sectional study, Voisin and colleagues (2011) found that exposure to community violence was associated with African American boys’ withdrawal, PTSD symptoms, and aggression, which in turn were associated with their connectedness to their teachers. For girls, exposure to community violence was linked to school engagement through aggressive behavior (Voisin, Neilands, & Hunnicutt, 2011). Longitudinal studies are rare, however, with some research suggesting that psychological symptoms associated with exposure to community violence can adversely affect academic outcomes (Rosenthal & Wilson, 2003), but other research finding no such support for mediation (e.g., Henrich et al., 2004). In sum, while prior cross-sectional research suggests that internalizing and externalizing responses to exposure to community violence may mediate the association between community violence and academic outcomes, less is known about the effects of exposure to community violence on academic achievement over time. Also lacking from the available literature are prospective studies examining whether and how the effects of exposure to community violence on later academic functioning varies for boys and girls.

Different patterns of association between exposure to community violence and aggression, depression, and anxiety for boys and girls suggest that the pathways linking exposure to community violence and academic adjustment may differ for boys and girls. For example, males generally report more self-protective (e.g., carrying a weapon) and aggressive behaviors in response to witnessing community violence (for a review see Fowler et al., 2009). On the other hand, several studies indicate that exposure to community violence is associated with anxious symptoms for girls, but not boys (White, Bruce, Farrell, & Kliewer, 1998). These differences are in line with propositions about gender socialization, and are consistent with gender schema theory (Bem, 1981) and social learning theory (Bandura, 1977). For example, youth may be expected to act in ways consistent with traditional gender roles and reinforced for such behaviors, including boys’ aggressive responses to exposure to community violence and girls’ more emotional responses. Given gender differences in emotional and behavioral consequences of exposure to community violence, different types of symptoms may link community violence and academic functioning for boys and girls. This study examines this possibility.

Present Study

Urban, particularly low-income, African American youth disproportionately reside in neighborhoods characterized by crime and violence, increasing their risk for exposure to community violence and its adverse effects, including problems in academic functioning (Henrich et al., 2004; Hurt et al., 2001; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003). However, reasons for the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning are not well understood. The current study used a longitudinal design to examine whether aggressive behavior and depressive and anxious symptoms mediate the association between exposure to community violence and academic performance in a community sample of urban African American adolescents. It was hypothesized that exposure to community violence would be associated with aggressive behaviors, and depressive and anxious symptoms, which in turn would be associated with lower academic functioning. Different mediating pathways were expected for boys and girls, given prior research indicating that during adolescence males and females differ in their responses to exposure to community violence (Farrell & Bruce, 1997; Voisin et al., 2011). Specifically, it was expected that the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning will be mediated by aggression for boys, and by depressive and anxious symptoms for girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were 491 African American middle school students originally assessed in the fall of first grade as part of a longitudinal study examining the impact of two school-based preventive intervention trials targeting early learning and aggressive behaviors. These students were drawn from a sample of 678 urban first graders were recruited from 27 first grade classrooms in 9 different elementary schools. Of the 678 children who participated in the intervention trial in first grade, 585 (86.3%) students were African American. Of the 585 African American youth in the original sample, 491 had written parental consent, provided verbal assent, and participated in the 6th, 7th, or 8th grade follow up assessments. These 491 participants comprised the sample of interest for this study. Of these 491, 401 (90.2%) had data in each of grades 6, 7, and 8; 35 (7.1%) had data at only two of the grades; and 13 (2.6%) had data at only one of the grades. At their sixth grade assessment, the sample ranged in age from 10 to 13 (M = 11.75). Approximately half (53.4 %) of the sample is male and 71.3 % of the sample is low socioeconomic status, as indicated by receipt of free or reduced-cost lunches. Chi square tests indicated that the 94 youth who did not participate in the grade 6th – 8th grade follow up assessments, did not differ from the youth in this study in terms of gender (χ2 = 1.94, ns), intervention status (χ2 = 1.18, ns), socioeconomic status (χ2 = .65, ns), or first grade aggressive behavior (t = 1.29, ns), depressive symptoms (t = .021, ns), or anxious symptoms (t = .68, ns).

Assessment Design

Adolescents reported about their exposure to community violence in grade 6. In grade 7, youth reported about their depressive and anxious symptoms, and teachers reported about aggressive behavior. Information about academic functioning was obtained through teacher reports about academic readiness and grades in grade 8 and participants’ scores on 8th grade standardized reading achievement tests. A face-to-face interview was used to gather data from the teachers and youth at each assessment point. This study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and verbal assent was obtained from the youth.

Measures

Exposure to Community Violence

Exposure to community violence was assessed using the Children’s Report of Violence Exposure (CREV; Cooley et al., 1995), a self-report instrument developed for children and adolescents to assess the frequency of exposure to community violence through three modes, witnessing, victimization, and hearsay (Cooley et al., 1995). Participants reported about their past year community violence victimization (i.e., whether they had been beaten up, robbed or mugged, shot or stabbed), witnessing (i.e., whether they had witnessed anyone being beaten up, robbed or mugged, shot or stabbed, or killed), and hearsay (i.e., if their family or peers witnessed or experienced the aforementioned events). These reports of victimization, witnessing, and hearsay were used as indicators of a latent variable representing exposure to community violence in the past year. The CREV has shown to be reliable in African American youth and to be related to psychological wellbeing (Cooley et al., 1995).

Aggression

Aggressive behavior was measured using the aggressive/disruptive behavior subscale of the Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation-Revised (TOCA-R; Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). The TOCA-R is a brief measure of each child’s adequacy of performance on the core tasks in the classroom as defined by the teacher. It is a structured interview administered by a trained member of the assessment staff. The interviewer records the teacher’s ratings of the adequacy of each child’s performance over of the past 3 weeks on a 6-point scale (1 = never true, 6 = always true) in the following domains: accepting authority (aggressive behavior); social participation (shy or withdrawn behavior); self-regulation (impulsivity); motor control (hyperactivity); concentration (inattention); and peer likeability (rejection). A summary aggression score was created by taking the mean of the 5-item aggressive/disruptive subscale (grade 7 α = .87). In terms of predictive validity, the aggressive/disruptive behavior subscale significantly predicted adjudication for a violent crime in adolescence and a diagnosis of Antisocial Personality Disorder at age 19–20 in the first generation JHU PIRC trial and follow-up (Petras, Chilcoat, Leaf, Ialongo, & Kellam, 2004; Schaeffer, Petras, Ialongo, Poduska, & Kellam, 2003).

Depressive and Anxious Symptoms

Anxious and depressive symptoms were assessed using the Baltimore How I Feel (BHIF; Ialongo, Kellam, & Poduska, 1999), a 45-item, youth self-report measure of depressive and anxious symptoms. The BHIF was designed as a first-stage measure in a two-stage epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence of child and adolescent mental disorders as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., rev.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Items were generated directly from DSM-IV criteria or drawn from existing child self-report measures, including the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1983), the Depression Self-Rating Scale (Asarnow & Carlson, 1985), the Hopelessness Scale for Children (Kazdin, Rodgers, & Colbus, 1986), the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1985), and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (Spence, 1997). Children reported the frequency of depressive and anxious symptoms over the last 2 weeks on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 4 = most times), recoded such that the items are scored 0 to 3 and a score of 0 indicates no symptoms. Summary scores were created by summing across the 19 depression items to yield a depression subscale score (grade 7 α = .82), and the remaining 26 items for the anxiety subscale score (grade 7 α = .87). In terms of predictive validity, the BHIF depression subscales are significantly associated with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), and the BHIF anxiety subscales were significantly associated with a diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV.

Academic functioning

Teachers reported about participants’ academic readiness and grades on the TOCA–R (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). The 7-item academic readiness scale assesses effort, attention, eagerness to learn, and engagement in academic activities. Items are scored on a 6-point scale (1 = “never true;” 6 = “always true”), with higher scores indicating greater academic readiness (eighth grade α = .95). Teachers reported about participants’ grades (α =.96) in their class over a period of 3 weeks on a 5-point scale (1 = excellent, 5 = failing). This scale is reversed coded with low scores indicating high performance. Reading achievement was measured using the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement-Brief and Comprehensive Forms (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1998). The K-TEA is an individually administered diagnostic battery that measures reading, mathematics, and spelling skills. The brief form of the K-TEA is designed to provide a global assessment of achievement in each of the latter areas. The K-TEA norms are based on a nationally representative sampling of over 3,000 children from grades 1–12, and internal consistency for the reading scale exceeded .90 in the norming sample. Teacher reported grades and academic readiness, and reading achievement were used as indicators of a latent variable representing academic functioning.

Results

Data Analytic Strategy

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the hypothesized associations among study constructs. A benefit of the SEM framework is that it allows for the simultaneous examination of variables in a single model, allowing one to account for other variables in the model (Hoyle & Smith, 1994). SEM allows for the examination of directional predictions and modeling of indirect effects. SEM it avoids problems of overestimation and underestimation of mediated effects by controlling for measurement error and permits estimation of models that include multiple mediators (Kline, 1998).

SEM was conducted using the Mplus 6.1 statistical package (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), and full information maximum likelihood estimates were obtained; this approach allows for missing data under missing at random (MAR; Little & Rubin, 1989; Rubin, 1987) assumptions. Overall model fit was evaluated using multiple indicators of fit: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest that CFI values above .95 indicate good fit. RMSEA values less than .08 and SRMR values less than .10 indicate acceptable fit (Kline, 1998).

To test mediation, the strength and significance of the indirect effects of exposure to community violence to the hypothesized mediators (i.e., aggressive behavior, depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms), and from these to the academic functioning (i.e., teacher-reported grades and academic readiness, reading achievement) were examined using the confidence interval based test recommended by MacKinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Multiple group analysis was used to examine gender differences. For these analyses, models were estimated under two conditions: when there were no constraints on the hypothesized moderated path for males and females (i.e., freely estimated model) and when the hypothesized moderated path was constrained to be equal for males and females (i.e., constrained model). A worse fit for the constrained model compared to the freely estimated model suggests moderation.

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate associations for study variables are presented in Table 1. Participants’ reports of exposure to community violence (through witnessing, victimization, and hearsay) ranged from 0 to 7 violent events (M = 1.19). In grade 6, approximately 59.6% of the sample reported exposure to community violence through witnessing, victimization, or hearsay in the past year. Boys and girls did not differ in their reports of exposure to community violence. There were no differences in boys’ and girls’ reports of their depressive or anxious symptoms, but teachers reported significantly more aggressive behavior for boys than for girls. Teachers reported significantly higher grades and academic readiness for girls than for boys. There were no gender differences in reading achievement.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations among Study Variables

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Community Violence (6th) | – | .15* | .26** | .19** | −.11 | .09 | .01 | |

| 2. Aggressive Behavior (7th) | .05 | – | .06 | .08 | −.38** | .29** | −.02 | |

| 3. Depressive Symptoms (7th) | .20** | .07 | – | .66** | −.24** | .23** | −.15* | |

| 4. Anxious Symptoms (7th) | .15* | −.00 | .76** | – | −.20** | .21** | −.17** | |

| 5. Academic Readiness (8th) | −.15* | −.32** | −.25** | −.22** | – | −.81** | .29** | |

| 6. Grades (8th) | .15* | .28** | .27** | .21** | −.86** | – | −.22** | |

| 7. Reading Achievement (8th) | .00 | −.12 | −.23* | −.22** | .25** | −.33** | – | |

| Males’ Mean (SD) | 1.29 (1.36) |

1.85 (.71) |

.60 (.35) |

.62 (.39) |

3.68 (1.09) |

3.16 (1.05) |

36.65 (6.69) |

|

| Females’ Mean (SD) | 1.08 (1.42) |

1.53 (.54) |

.66 (.44) |

.67 (.44) |

4.43 (1.01) |

2.61 (.96) |

36.71 (5.56) |

|

| t- test | 1.64 | 5.35** | −1.68 | −1.32 | 7.58** | 5.81** | .09 | |

Note. Correlations for males are above the diagonal; correlations for females are below the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Exposure to community violence and aggression were associated positively for boys, but not girls. Exposure to community violence was associated positively with depressive symptoms and with anxious symptoms for boys and girls. Aggression was associated positively with grades and negatively associated with academic readiness for girls and boys, but was not associated with reading achievement. For boys and girls, depressive symptoms were associated with lower grades, less academic readiness, and lower reading achievement. Similarly, for boys and girls, anxious symptoms were associated with lower grades, less academic readiness, and lower reading achievement.

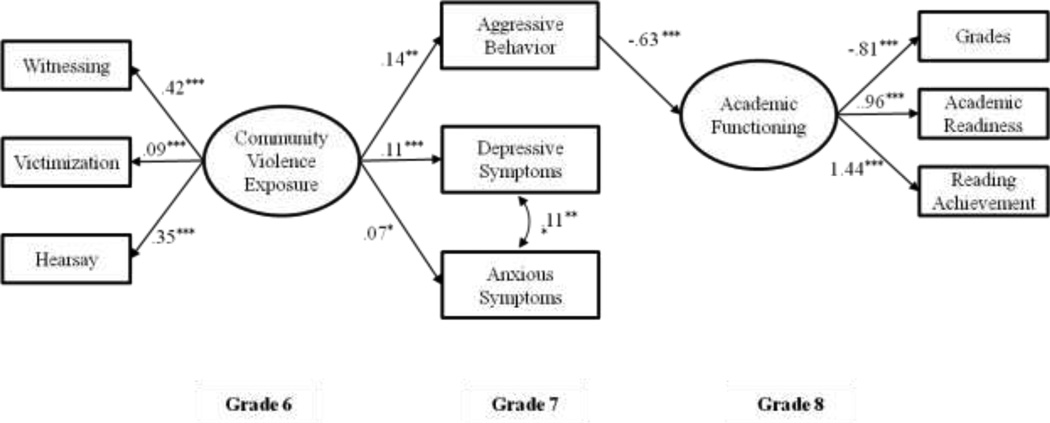

Structural equation modeling

To test the indirect effects of grade 6 exposure to community violence on grade 8 academic functioning and achievement, we estimated a model containing paths from exposure to community violence in grade 6 to aggression, depressive and anxious symptoms in grade 7, and from these to academic performance and achievement in grade 8 (see Figure 1). As noted above, exposure to community violence was a latent variable with witnessing, victimization, and hearsay as indicators. Academic functioning was a latent variable with teacher-reported grades, teacher-reported academic readiness, and reading achievement as indicators. Intervention status and lunch status were controlled in all models, and grade 7 depressive and anxious symptoms were allowed to correlate. The indirect model fit the data well (χ2(39) = 86.57, p < .001; CFI = .96; RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = .06.), with the significant chi-square likely reflecting its sensitivity to sample size (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980). In this model, exposure to community violence in grade 6 was associated positively with aggressive behavior in grade 7 (β = .14, p < .01), which in turn was associated negatively with teacher-rated academic performance in grade 8 (β = −.71, p < .001). Exposure to community violence in grade 6 was associated positively with grade 7 depressive symptoms (β = .11, p < .001) and anxiety symptoms (β = .07, p < .05), however, neither was associated with grade 8 teacher-reported academic functioning. There was a significant indirect effect from community violence  aggressive behavior

aggressive behavior  academic functioning (β = −.10, p < .01; 95% CI: −.16, −.04), suggesting that aggressive behavior mediates the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning. Neither intervention status nor lunch status were associated with academic functioning. The addition of the direct path from exposure to community violence to academic functioning did not improve model fit (Δχ2(1) = 2.57, ns) and the path from exposure to community violence to academic functioning was not significant in this model, also consistent with mediation.

academic functioning (β = −.10, p < .01; 95% CI: −.16, −.04), suggesting that aggressive behavior mediates the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning. Neither intervention status nor lunch status were associated with academic functioning. The addition of the direct path from exposure to community violence to academic functioning did not improve model fit (Δχ2(1) = 2.57, ns) and the path from exposure to community violence to academic functioning was not significant in this model, also consistent with mediation.

Figure 1.

Standardized coefficients for indirect pathway from 6th grade community violence exposure to 8th grade academic outcomes.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

It was hypothesized that the indirect effect of exposure to community violence  aggressive behavior

aggressive behavior  academic functioning differed for boys and girls due to differences in the association between community violence and aggression for boys and girls. To test this hypothesis, a model with this path freely estimated for boys and girls was compared to a model with this path constrained to be equal for boys and girls. These models were not significantly different (Δχ2 = .57, ns), suggesting that gender did not moderate the path between exposure to community violence and aggressive behavior.

academic functioning differed for boys and girls due to differences in the association between community violence and aggression for boys and girls. To test this hypothesis, a model with this path freely estimated for boys and girls was compared to a model with this path constrained to be equal for boys and girls. These models were not significantly different (Δχ2 = .57, ns), suggesting that gender did not moderate the path between exposure to community violence and aggressive behavior.

Discussion

The overrepresentation of urban African American adolescents in low income and high crime neighborhoods increases their risk of exposure to community violence (CDC, 2010) and its adverse outcomes, including lowered academic performance (Henrich et al., 2004; Schwartz & Gorman, 2003). However, mechanisms linking exposure community violence and educational outcomes are not well understood, limiting the ability to develop useful interventions for these youth. The present study investigated whether aggression, depression, and anxiety mediated the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning in a community sample of urban African American adolescents. Aggressive behavior mediated the association between exposure to community violence and academic performance and this pattern was evident for males and females. The results of this research have implications for prevention and intervention efforts to decrease low academic performance among community violence exposed youth.

That aggression mediated the association between exposure to community violence and academic achievement in this longitudinal study is consistent with prior cross-sectional research with urban youth (Schwartz & Gorman, 2003; Voisin et al., 2011). In a cross-sectional study, Schwartz and Gorman (2003) found that disruptive behaviors mediated the association between urban elementary school children’s exposure to community violence and their academic achievement. Likewise, Voisin and colleagues (2011) found that aggression mediated the association between exposure to community violence and grade point average for African American high school females. Community violence exposed adolescents may begin to believe that aggressive and violent responses are normal and effective, which can lead to increased aggression and misbehavior (Miller, Wasserman, Neugebauer, Gorman-Smith, & Kamboukos, 1999) and negatively impact their academic performance. In addition to out of class time for misbehavior, adolescents with aggressive behaviors are more likely to be in detention and suspension (McConville & Cornell, 2003; Sugai & Horner, 2008). Thus, they likely have fewer positive interactions with teachers and peers, less time for classroom instruction, and reduced opportunities to participate in school activities; each has been linked to lower academic performance and school engagement (Sugai & Horner, 2008).

While exposure to community violence was associated with depressive and anxious symptoms, there was no association between these symptoms and academic functioning or achievement. In contrast, Schwartz and Gorman (2003) found that urban elementary school children exposed to community violence displayed depressive and anxious symptoms, and these symptoms were linked to poor academic performance (Schwartz & Gormam, 2003). Likewise, in study of African American high school students, Voisin and colleagues (2011) found that males exposed to community violence experienced symptoms of depression and anxiety, and these symptoms negatively affected student-teacher connectedness. It is possible that depressive and anxious symptoms were not associated with academic achievement because, unlike adolescents who are aggressive, adolescents with depressive and anxious symptoms may be less defiant and defensive with teachers; this difference in behavioral style may increase teachers’ willingness to provide these adolescents with additional academic support such as after school tutoring. Aggressive behavior, on the other hand, may limit teachers’ and peers’ willingness to provide academic support and decrease adolescents overall academic achievement (Farrell & Bruce, 1997; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998). Therefore, depressive and anxious symptoms may be less of a risk factor for low academic performance than aggressive behaviors.

Contrary to expectation, there were no gender differences in the association between exposure to community violence and aggressive behaviors, and aggressive behavior emerged as a mechanism linking exposure to community violence and academic performance for boys and girls. Similarly, other studies have not found gender differences in the effect of exposure to community violence on aggression (Mrug, Loosier, & Windle, 2008; Schwab-Stone et al., 1999; Schwartz & Proctor, 2000). Research suggests that parents living in violent neighborhoods may be less likely to try to reduce adolescents’ aggressive behavior because they believe that aggressive behavior is necessary for adolescents to defend themselves (Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanov, 1994); instead, parents may communicate the value of aggressive behavior as protective against exposure to community violence regardless of their child’s gender; if so, males and females exposed to community violence might display similar aggressive behaviors. Relatedly, aggressive behaviors may be perceived as normative in violent contexts and girls and boys may display similar levels and types of aggression in these settings (e.g., Hudley et al., 2001; McMahon, Felix, Halpert, & Petropoulos, 2009).

Our results should be considered in light of the study’s limitations. Given this study’s focus on individual behavior linking exposure to community violence and academic functioning, family and school level variables relevant for academic functioning were not examined. It is possible that family (e.g., parental involvement, family functioning) and school (e.g., school engagement, school cohesion) factors can provide social and emotional support that motivate adolescents to achieve and may protect against poor academic performance (Gorman-Smith et al., 2004), and school-level effects can have implications for academic performance (e.g., Koth, Bradshaw, & Leaf, 2008; Stewart, 2008). Regarding measurement, while it is generally accepted that adolescents are well equipped to report about their depressive and anxious symptoms (Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, & Gipson, 2004), multiple reporters of adolescents’ depressive and anxious symptoms would have been beneficial as the lack of association between adolescent reports of depressive and anxious symptoms and academic functioning may have occurred due to a rater effect. In addition, because aggressive behaviors were measured using teacher reports, these findings reflect aggressive behavior in the school context; aggression in other contexts also may be relevant for academic functioning. Finally, these results likely generalize only to African American youth from similar socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study suggests several implications for practice. Given the adverse behavioral and educational consequences of being exposed to community violence, it is important for educators and counselors to conduct assessments of exposure to community violence. Exposure to community violence is often undetected by service providers (Guterman & Cameron, 1999; Voisin, 2007); increasing public awareness of the scope of exposure to community violence and the use of standardized measures of assessing exposure to community violence in practice settings may be useful (Voisin, 2007). In addition, the association between exposure to community violence and depressive and anxious symptoms highlights the need for regular assessments of these problems in youth who have been exposed to community violence.

Implementation of community and school-based preventive interventions addressing community violence for youth exposed or at risk of exposure may be helpful for many urban youth and help prevent aggressive behaviors before they occur, and interventions aimed at preventing or reducing aggression may be useful. For example, Coping Power (Lochman & Wells, 1996), a preventive intervention focusing on social competence, self-regulation, and positive parental involvement, and the Positive Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS; Kusche & Greenberg, 1994) program focusing on increasing self-control, emotional awareness, and interpersonal problem solving skills, each have demonstrated effects for aggressive behaviors (e.g., Curtis & Norgate, 2007; Kam, Greenberg, & Walls, 2003). In addition, given the link between exposure to community violence and academic performance through aggression, educational policies should include interventions aimed at decreasing adolescents’ aggressive behaviors. Aggressive adolescents’ disruptive behaviors and rule breaking may lead to several disciplinary actions, such as in-school detentions and school suspensions, which interfere with utilities for learning (Raby, 2012). These types of interventions to punish aggressive behaviors can inadvertently negatively affect students’ academic performance. Alternative disciplinary strategies such as School Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS; Bradshaw, Mitchell, & Leaf, 2010) should be considered, and prevention strategies that promote effective problem solving strategies and non-aggressive behaviors (e.g., social skills training; Darensbourgh, Perez, & Blake, 2010; Fenning & Rose, 2007) should be integrated into the academic curriculum.

Findings from this study add to the literature examining the role of exposure to community violence in adolescents’ academic functioning. Results indicate that aggressive behavior is one mechanism linking exposure to community violence and academic functioning for African American boys and girls. This finding is particularly important given low income urban African American adolescents’ disproportionate exposure to community violence (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006), and the seemingly parallel disparities in academic outcomes (Vanneman, Hamilton, Baldwin Anderson, & Rahman, 2009). To optimally inform interventions to eradicate these longstanding academic achievement disparities and improve academic outcomes, future research will benefit from the identification of specific types of aggressive behaviors (e.g., verbal aggression, fighting, destructive behavior) most relevant for understanding the association between exposure to community violence and academic functioning to inform intervention efforts. In addition, understanding achievement-related mechanisms that link exposure to community violence and academic functioning is important. For example, youth exposed to community violence may have a sense of foreshortened future (Gellman & DeLucia-Waack, 2006; Wright & Steinbach, 2001) or perceive limited life opportunities (Davis & Siegle, 2000); these may lessen adolescents’ future academic expectations and achievement motivation, and therefore possibly also their academic achievement (Wigfield &, Eccles, 2002). Finally, it is important to note that not all adolescents who are exposed to community violence experience negative consequences. Future research should examine factors that promote resilience within these youth. Prior research highlights racial identity and racial socialization as protective factors against low academic achievement for African American adolescents (Byrd & Chavous, 2009; Evans et al., 2012). Identifying relevant protective factors for African American youth will allow researchers to develop and implement optimal interventions for youth exposed to community violence and promote academic success for these youth.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH057005: PI Ialongo; MH078995: PI Lambert) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11796: PI Ialongo). We thank the Baltimore City Public Schools for their collaborative efforts and the parents, children, teachers, principals, and school psychologists and social workers who participated in this study.

DB conceived the study, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; SL conceived the study, performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript; NI was responsible for the design and coordination of the study, and performed the measurement. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Biographies

Danielle R. Busby is a clinical psychology doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at George Washington University. Her research focuses on the effects of community violence exposure in urban minority youth, academic achievement, and school and community-based prevention and intervention methods.

Sharon F. Lambert is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at George Washington University. Her research focuses on the etiology, correlates, and course of depressive symptoms in urban and ethnic minority youth, community violence exposure, and school-based prevention.

Nicholas S. Ialongo is a professor in the Department of Mental Health in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Prevention and Early Intervention. His research focuses on the design, implementation, and evaluation of universal preventive interventions to prevent mental health and substance use disorders.

References

- Aguirre A, Turner JH, Aguirre A., Jr . American ethnicity: The dynamics and consequences of discrimination. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson GA. Depression self-rating scale: Utility with child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(4):491–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Basch CE. Aggression and violence and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. Journal of School Health. 2011;81(10):619–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. Bem Sex Role Inventory: Professional manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonnet DC. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88(3):588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NK, Bowen GL. Effects of crime and violence in neighborhoods and schools on the school behavior and performance of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14(3):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Mitchell M, Leaf P. Examining the effects of Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on student outcomes: results from a randomized controlled effectiveness trial in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2010;12(3):133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. National crime victimization survey: Criminal victimization, 2005 (US Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin NCJ 214644) 2006 Retrieved from: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/

- Byrd C, Chavous T. Racial identity and academic achievement in the neighborhood context: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(4):544–559. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Crockett LJ, Carranza MA. Health disparities in youth and families: Research and applications. New York, NY US: Springer Science Business Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce A, Cruz R, Corona M, Conger R. The face of the future: Risk and resilience in minority youth. In: Carlo G, Crockett LJ, Carranza MA, editors. Health disparities in youth and families: Research and applications. New York, NY US: Springer Science Business Media; 2011. pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing youth violence. 2010 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov.

- Chapman C, Laird J, Kewal Ramani A. Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: (1972–2009), Compendium Report. Washington, DC: National Centre for Education Statistics; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley MR, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Assessing community violence: The children's report of exposure to violence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(2):201–208. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Quille M, Boyd RC, Frantz E, Walsh J. Emotional and behavioral impact of exposure to community violence in inner-city adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(2):199–206. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3002_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C, Norgate R. An evaluation of the promoting alternative thinking strategies curriculum at key stage 1. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2007;23(1):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Da Fonseca D, Cury F, Fakra E, Rufo M, Poinso F, Bounoua L, et al. Implicit theories of intelligence and IQ test performance in adolescents with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2008;46(4):529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darensbourg A, Perez E, Blake J. Overrepresentation of African American males in exclusionary discipline: The role of school-based mental health professionals in dismantling the school to prison pipeline. Journal of African American Males in Education. 2010;1(3):196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Siegel LJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A review and analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(3):135–154. doi: 10.1023/a:1009564724720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov P. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65(2):296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Getts A, Cadenhead C, Emans SJ. Exposure to violence and victimization and depression, hopelessness, and purpose in life among adolescents living in and around public housing. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1995;16(4):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AB, Banerjee M, Meyer R, Aldana A, Foust M, Rowley S. Racial Socialization as a mechanism for positive development among African American youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Bruce SE. Impact of exposure to community violence on violent behavior and emotional distress among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(1):2–14. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning P, Rose J. Overrepresentation of African American students in exclusionary discipline the role of school policy. Urban Education. 2007;42(6):536–559. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM. Exposure to violence and presence of depression among low-income, African-American youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(3):528–531. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB. Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröjd SA, Nissinen ES, Pelkonen MUI, Marttunen MJ, Koivisto AM, Kaltiala-Heino R. Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(4):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellman RA, DeLucia-Waack JL. Predicting school violence: A comparison of violent and nonviolent male students on attitudes toward violence, exposure level to violence, and PTSD symptomatology. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43(5):591–598. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, Morris SZ, Beaver KM. Secondary exposure to violence during childhood and adolescence: Does neighborhood context matter? Justice Quarterly. 2009;26(1):30–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10(1):101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: The protective effects of family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):412–425. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Rowell Huesmann L, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development. 2003;74(5):1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman N, Cameron M. Young clients' exposure to community violence: How much do their therapists know? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69(3):382–391. doi: 10.1037/h0080412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday-Boykins CA, Graham S. At both ends of the gun: Testing the relationship between community violence exposure and youth violent behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(5):383–402. doi: 10.1023/a:1010443302344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Richards MH, Luo Z, Edlynn ES, Roy K. Social support factors as moderators of community violence exposure among inner-city African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):450–462. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M, Fanti K, Jones SM, Ruchkin V. The association of community violence exposure with middle-school achievement: A prospective study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2004;25(3):327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Anderson A. Enhancing social competence: Integrating selfmanagement strategies with behavioral procedures for children with ADHD. In: Hibbs ED, Jensen PS, editors. Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1996. pp. 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Feigelman S, Li X, Cross S, Rachuba L. The relationship among violence victimization, witnessing violence, and youth distress. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(6):455–462. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Smith GT. Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:429–440. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hudley C, Wakefield WD, Britsch B, Cho S, Smith T, DeMorat M. Multiple perceptions of children's aggression: Differences across neighborhood age, gender, and perceiver. Psychology In The Schools. 2001;38(1):43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt H, Malmud E, Brodsky NL, Giannetta J. Exposure to violence: Psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(12):1351–1356. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2005;8(3):145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N, Edelsohn G, Werthamer-Larsson L, Crockett L, Kellam S. The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first grade children: Prediction to anxious symptoms and adaptive functioning in fifth grade. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;36(3):427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N, Kellam S, Poduska J. Manual for the Baltimore how I feel. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kam C, Greenberg MT, Walls CT. Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based prevention using the PATHS curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4(1):55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1021786811186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Kaufman N. Manual for the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement: Brief form. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, Colbus D. The hopelessness scale for children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54(2):241–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koth CW, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ. A multilevel study of predictors of student perceptions of school climate: The effect of classroom-level factors. Journal Of Educational Psychology. 2008;100(1):96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children's depression inventory: A self-rated depression scale for school-age youngsters. University of Pittsburgh; 1983. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kusche CA, Greenberg MT. The PATHS curriculum. Seattle, WA: Developmental Research and Programs; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Swisher RR. The interactive relationship among adolescent violence, street violence, and depression. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33(3):355–371. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Brain mechanisms of emotion and emotional learning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1992;2:191–198. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;18(2-3):292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Coping Power program: Child component. Unpublished manual. Durham, NC: Duke University Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7 (1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51(1):445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Peer relationships and psychopathology in developmental perspective: Reflections on progress and promise. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):87–92. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza JJ, Reynolds WM. Exposure to violence in young inner-city adolescents: Relationships with suicidal ideation, depression, and PTSD symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27(3):203–213. doi: 10.1023/a:1021900423004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone LL, Ducci FF, Scoto MC, Passaniti EE, D'Arrigo VG, Vitiello BB. The role of anxiety symptoms in school performance in a community sample of children and adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(347) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCart MR, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Ruggiero KJ. Do urban adolescents become desensitized to community violence? Data from a national survey. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(3):434–442. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConville DW, Cornell DG. Aggressive attitudes predict aggressive behavior in middle school students. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(3):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AS. The prevalence and effects of test anxiety in school children. Educational Psychology. 2001;21(1):89–101. [Google Scholar]

- McGee ZT. Community violence and adolescent development an examination of risk and protective factors among African American youth. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2003;19(3):293–314. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon SD, Felix ED, Halpert JA, Petropoulos LAN. Community violence exposure and aggression among urban adolescents: Testing a cognitive mediator model. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(7):895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Miller C. Direct, mediated, moderated, and cumulative relations between neighborhood characteristics and adolescent outcomes. Adolescence. 2004;39(153):121–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles S, Stipek D. Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development. 2006;77(1):103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Wasserman GA, Neugebauer R, Gorman-Smith D, Kamboukos D. Witnessed community violence and antisocial behavior in high-risk, urban boys. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28(1):2–11. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Loosier PS, Windle M. Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(1):70–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplususers guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Monitoring quality: An indicators report. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Stueve C. Pathologic adaptation to community violence among inner-city youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(2):196–208. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky JD. The effect of exposure to violence on young children. American Psychologist. 1995;50(9):782–788. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.9.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet S, Braun S. A preliminary examination of the relationship between exposure to community violence and academic functioning. School Psychology Quarterly. 1999;14(4):380–396. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ. The impact of violence on urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20(2):167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Weinstein RS. Urban adolescents' exposure to community violence: The role of support, school safety, and social constraints in a school-based sample of boys and girls. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):463–476. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks-Stamm EJ, Heilman ME, Hearns KA. Motivated to penalize: Women's strategic rejection of successful women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(2):237–247. doi: 10.1177/0146167207310027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD. Incubated in terror: Neurodevelopmental factors in the ‘cycle of violence.’. Children in a Violent Society. 1997:124–149. [Google Scholar]

- Petras H, Chilcoat HD, Leaf PJ, Ialongo NS, Kellam SG. Utility of TOCA-R scores during the elementary school years in identifying later violence among adolescent males. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43 (1):88–96. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Kaufman J, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Dahl RE, Lukens E, Nelson B. The psychosocial functioning and family environment of depressed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(2):244–253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purugganan OH, Stein REK, Silver EJ, Benenson BS. Exposure to violence and psychosocial adjustment among urban school-aged children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24(6):424–430. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raby R. School rules: Obedience, discipline, and elusive democracy. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Frost AK, Pakiz B. Changing faces: Correlates of depressive symptoms in late adolescence. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance. 1991;14(1):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS): Manual. WPS, Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Larson R, Miller BV, Luo Z, Sims B, Parrella DP, McCauley C. Risky and protective contexts and exposure to violence in urban African American young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):138–148. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Ng - Mak DS. Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(5):489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal BS. Exposure to community violence in adolescence: Trauma symptoms. Adolescence. 2000;35(138):271–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal B, Wilson W. Impact of exposure to community violence and psychological symptoms on college performance among students of color. Adolescence. 2003;38(150):239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. The calculation of posterior distributions by data augmentation: Comment: A noniterative sampling/importance resampling alternative to the data augmentation algorithm for creating a few imputations when fractions of missing information are modest: The SIR algorithm. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82(398):543–546. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchkin V, Henrich CC, Jones SM, Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M. Violence exposure and psychopathology in urban youth: The mediating role of posttraumatic stress. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(4):578–593. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo NS, Poduska J, Kellam S. Modeling growth in boys' aggressive behavior across elementary school: Links to later criminal involvement, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39 (6):1020–1035. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39 (1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone M, Chen C, Greenberger E, Silver D, Lichtman J, Voyce C. No safe haven II: The effects of violence exposure on urban youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(4):359–367. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gorman AH. Community violence exposure and children's academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95(1):163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Proctor LJ. Community violence exposure and children's social adjustment in the school peer group: The mediating roles of emotion regulation and social cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):670–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selner-O'Hagan MB, Kindlon DJ, Buka SL, Raudenbush SW, Earls FJ. Assessing exposure to violence in urban youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39(2):215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Henrich CC, Winokur A, Blatt SJ, Kuperminc GP, Leadbeater BJ. Self-criticism and depressive symptomatology interact to predict middle school academic achievement. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(1):147–155. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: A confirmatory factoranalytic study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):280–297. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Kean YM. Disability and quality of life in social phobia: Epidemiologic findings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1606–1613. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EB. School structural characteristics, student effort, peer associations, and parental involvement: The influence of school- and individual-level factors on academic achievement. Education And Urban Society. 2008;40(2):179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, Horner RH. What we know and need to know about preventing problem behavior in schools. Exceptionality. 2008;16(2):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vanneman A, Hamilton L, Anderson JB, Rahman T. Achievement gaps: How black and white students in public schools perform in mathematics and reading on the national assessment of educational progress NCES 2009-455. 2009 Retrieved from: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/pdf/studies/2009455.pdf.

- Voisin D. The effects of family and community violence exposure among youth: Recommendations for practice and policy. Journal of Social Work Education. 2007;43(1):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Neilands TB, Hunnicutt S. Mechanisms linking violence exposure and school engagement among African American adolescents: Examining the roles of psychological problem behaviors and gender. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam S, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19(4):585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KS, Bruce SE, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Impact of exposure to community violence on anxiety: A longitudinal study of family social support as a protective factor for urban children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7(2):187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS. Development of Achievement Motivation. Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Stover CS, Berkowitz SJ. Research review: The relationship between childhood violence exposure and juvenile antisocial behavior: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(7):769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ. Parental intrusiveness and children's separation anxiety in a clinical sample. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2006;37(1):73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RJ, Steinbach SF. Violence: An unrecognized environmental exposure that may contribute to greater asthma morbidity in high risk inner-city populations. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2001;109(10):1085–1090. doi: 10.1289/ehp.011091085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick H, Hanson R, Smith D, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Prevalence and mental health correlates of witnessed parental and community violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2009;50(4):441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]