Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral (ARV) management in pediatrics is a challenging process in which multiple barriers to optimal therapy can lead to poor clinical outcomes. In a pediatric HIV clinic, we implemented a systematic ARV stewardship program to evaluate ARV regimens and make recommendations for optimization when indicated.

Methods

A comprehensive assessment tool was used to screen for issues related to genotypic resistance, virologic/immunologic response, drug-drug interactions, side effects, and potential for regimen simplification. The ARV stewardship team (AST) made recommendations to the HIV clinic provider, and followed patients prospectively to assess clinical outcomes at 6 and 12 months.

Results

The most common interventions made by the AST included regimen optimization in patients on suboptimal regimens based on resistance mutations (35.4%), switching to safer ARVs (33.3%), and averting significant drug-drug interactions (10.4%). In patients anticipated to have a change in viral load (VL) as a result of the AST recommendations, we identified a significant benefit in virologic outcomes at 6 and 12 months when recommendations were implemented within 6 months of ARV review. Patients who had recommendations implemented within 6 months had a 7-fold higher probability of achieving a 0.7 log10 reduction in VL by 6 months, and this benefit remained significant after controlling for adherence [adjusted OR 6.8 (95% CI 1.03-44.9, p <0.05)].

Conclusions

A systematic ARV stewardship program implemented at a pediatric HIV clinic significantly improved clinical outcomes. ARV stewardship programs can be considered a core strategy for continuous quality improvement in the management of HIV-infected children and adolescents.

Keywords: antiretroviral stewardship, quality improvement, human immunodeficiency virus, pediatrics

Introduction

Management of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in pediatric patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a challenging process in which providers need to consider the therapeutic goals of CD4 gains and viral load (VL) suppression along with the complications associated with long-term therapy such as toxicities and accumulation of resistance associated mutations (RAMs)1. For infants and young children with perinatally-acquired HIV, the limited availability of suitable drug formulations and lack of dosing recommendations for newer agents can limit the use of more potent and better-tolerated antiretrovirals (ARVs). For adolescents, multiple cognitive, mental health, and psychosocial factors such as lack of family support and risk-taking behaviors can serve as barriers to medication adherence, which can lead to virologic failure2-4.

Medication errors such as drug omissions, dosing errors, and major drug-drug interactions, occur in up to 86% of HIV-infected inpatients5,6,7. Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been advocated to optimize antimicrobial selection, dosing, route, and duration of therapy to maximize clinical cure while limiting unintended consequences, such as emergence of resistance, adverse drug events, and cost8. The same core strategies recommended for ASPs could be applied to optimize therapy in HIV-infected individuals. Several studies have investigated the role of various interventions on reducing medication errors in hospitalized HIV-infected patients7,9-18, as well as in the outpatient HIV clinic setting19-25. However, few studies assessed the appropriateness of ARV regimens based on resistance testing21,24, and few evaluated clinical outcomes such as CD4 gains and VL suppression21,22,24. Furthermore, no studies have been conducted in the pediatric HIV population.

As pediatric patients grow into adults and as newer drugs and pediatric formulations become available, there is a need for continuous optimization and simplification of ARV regimens. In July 2010, an ARV stewardship quality improvement (QI) program was implemented at our outpatient pediatric HIV clinic to systematically review and evaluate medication regimens prescribed to our patients. ARV-related issues identified were discussed with the patients’ HIV clinic provider, and the ARV stewardship team (AST) made recommendations for therapy optimization. The purpose of this prospective observational study was to (1) characterize the ARV-related issues identified and types of interventions recommended by the AST, (2) determine the proportion of interventions implemented by the HIV clinic provider, and (3) evaluate clinical outcomes at 6 and 12 months after initial review by the AST.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

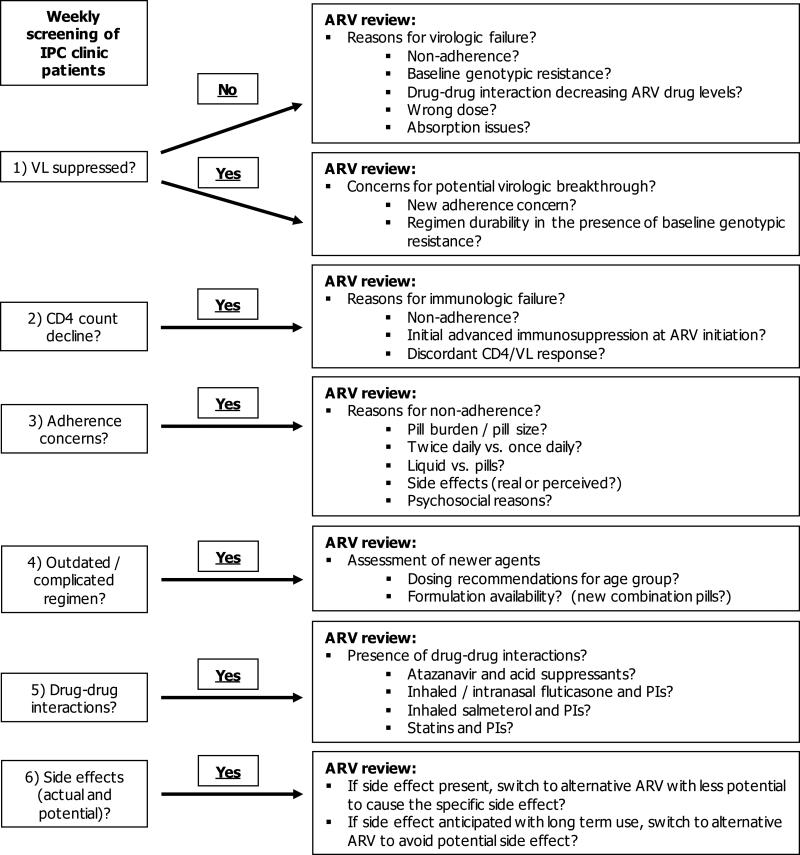

Starting July 2010, a pediatric infectious diseases physician and pediatric infectious diseases clinical pharmacist, both with specialized HIV training, systematically reviewed patients followed at the outpatient Intensive Primary Care (IPC) Clinic at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The IPC clinic providers consisted of pediatric infectious diseases trained physicians, adolescent medicine trained physicians, and nurse practitioners, with an average of 13 years of experience (range 5-25 years) managing HIV-infected children and adolescents. Patients were screened using a comprehensive assessment tool (Figure 1), which screened for issues related to (1) regimen appropriateness based on cumulative genotypic resistance profiles and ARV exposure history, (2) virologic and immunologic response, (3) drug-drug interactions, (4) short and long-term adverse effects, and (5) potential for regimen simplification to enhance adherence. ARV-related issues identified and recommendations for changes were discussed at the weekly multidisciplinary IPC clinic meeting with the patients’ HIV clinic provider, and it was at the discretion of the clinic provider whether or not recommendations would be implemented. This QI study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at The Johns Hopkins Hospital with a waiver of informed consent.

Figure 1.

Antiretroviral stewardship assessment tool

NOTE: ARV = antiretroviral, VL = viral load, IPC = intensive primary care, PI = protease inhibitor

Data collection

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were collected from electronic medical records on the date of review by the AST, and patients were prospectively followed to assess whether or not interventions recommended were implemented and time to implementation was calculated. Clinical outcomes relevant to the intervention recommended were also prospectively assessed from the electronic medical records (e.g. CD4/VL change, resolution of side effect, resolution of drug-drug interaction). For interventions in which a change in CD4 and/or VL was anticipated as a result of the recommendations made by the AST, change in CD4 count and VL at 6 and 12 months was calculated from the time of ARV review.

Definitions

Baseline adherence was defined as adherent vs. not by the HIV clinic provider when patients were discussed at our multidisciplinary clinic meeting. Adherence determination was made by mechanisms that included but were not limited to the following: patient/caregiver admission of incomplete adherence, persistent viremia despite reported adherence to the drug regimen and without other plausible explanation (e.g., drug interactions), pill counts inconsistent with reported pill intake (if applicable), pharmacy prescription refill history consistent with incomplete adherence (if available), drug levels (if measured), and knowledge of the social situation/family dynamics. Previous ARV exposure was defined as “treatment experienced” if the patient had been exposed to less than 2 previous cART regimens, and “extensively treatment experienced” if the patient had been exposed to 2 or more previous cART regimens. All available genotypes were reviewed to compile a cumulative genotype for each patient. Patients’ prior ARV exposure was also taken into account when considering possible resistance. For example, in patients with extensive nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) exposure with multiple thymidine analogue mutations (TAMs), an M184V was inferred even if it did not appear on the patients’ genotypes. Genotypic resistance was assessed according to the most updated International AIDS Society (IAS) resistance mutations list26-29 that was available at the time of ARV review, and ARV regimens were considered “suboptimal” if the overall summative activity was less than 2 fully active agents (i.e. regimens could have had multiple partially active agents that, taken together, were the equivalent of a regimen containing less than 2 fully active agents). Regimen optimization was defined as a recommendation that would change the patients’ cART regimen from <2 fully active agents to at least 2 fully active agents from 2 different classes.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest included the median change in CD4 count and VL, and proportion of patients achieving a decline in VL of at least 0.7 log10 at 6 and 12 months after ARV review. These outcomes were assessed in patients in whom a change in CD4 and/or VL was anticipated as a result of the recommendations made by the AST. Outcomes were compared between those with recommendations implemented within 6 months of ARV review vs. those in which recommendations were not implemented within 6 months. Secondary outcomes of interest included resolution of side effects and drug-drug interactions.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range (IQR), frequencies and percentages). Comparisons were made using chi-squared (χ2) test for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous data. Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the outcome of achieving a decline in VL of at least 0.7 log10 by 6 and 12 months after ARV review. All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software version 13.1 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX); a 2-sided P value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

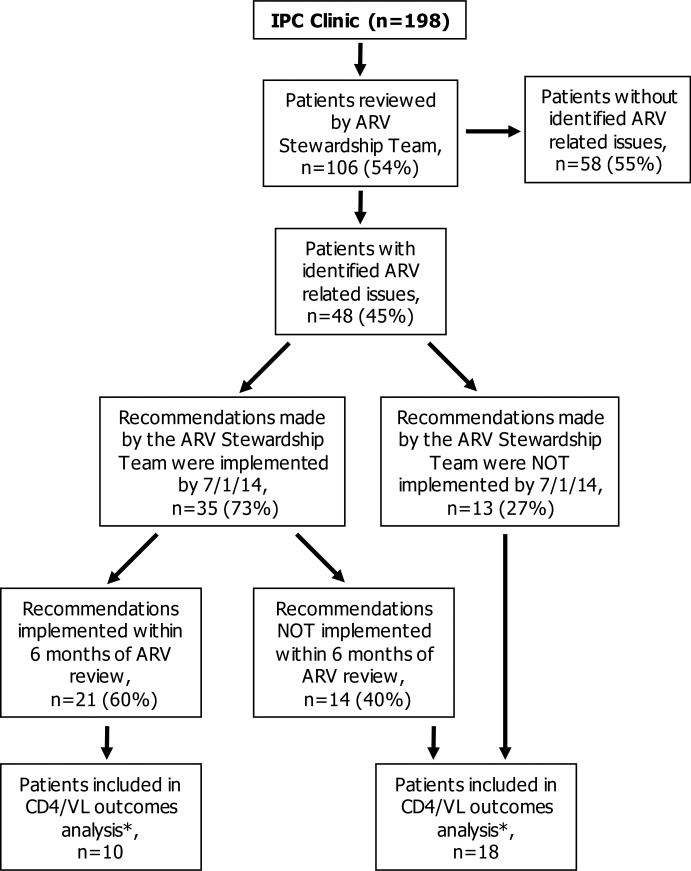

The AST reviewed 106 of 198 (54%) IPC clinic patients between July 2010 and March 2014 (Figure 2). ARV-related issues were identified in 48 of 106 (45%) patients reviewed. When patients with identified ARV-related issues (n=48) were compared to those without (n=58), patients with identified ARV-related issues tended to be younger (median (IQR) age 18.5 (10.5-21) vs. 20 (16-21.5) years, p 0.08), perinatally-infected (95.8% vs. 75.9%, p < 0.01), and had lower baseline CD4 counts (median (IQR) 523.5 (340-897.5) vs. 672.5 (444-776) cells/mm3, p 0.16). Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the 48 patients with identified ARV-related issues are shown in Table 1. 72.9% of patients were extensively treatment experienced, 75% had reverse transcriptase (RT) RAMs, and 58.3% had protease (PR) RAMs. The most common cART regimen prescribed at the time of ARV review was lopinavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs. 47.9% of patients were determined by their providers to be non-adherent.

Figure 2.

Selection of patients for study inclusion

* Included patients in whom a change in CD4 and/or VL was anticipated as a result of the recommendations made by the ARV stewardship team

NOTE: ARV = antiretroviral, VL = viral load, IPC = intensive primary care

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of 48 patients with identified antiretroviral-related issues

| Baseline characteristics | Result |

|---|---|

| Age at time of ARV review (years), median (IQR) | 18.5 (10.5-21) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 30 (62.5) |

| Male | 18 (37.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African-American | 40 (83.3) |

| White | 5 (10.4) |

| Mixed/Other | 3 (6.3) |

| HIV acquisition, n (%) | |

| Perinatal | 46 (95.8) |

| Non-perinatal | 2 (4.2) |

| Previous ARV exposure*, n (%) | |

| Extensively treatment experienced | 35 (72.9) |

| Treatment experienced | 13 (27.1) |

| CD4 (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 523.5 (340-897.5) |

| CD4 nadir (cells/mm3), median (IQR) | 245 (18.5-548.5) |

| Viral load (log10), median (IQR) | 2.1 (1.69-3.88) |

| Any reverse transcriptase resistance mutations at baseline, n (%) | 36 (75) |

| Any protease resistance mutations at baseline, n (%) | 28 (58.3) |

| cART prescribed at time of review, n (%) | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs | 19 (39.6) |

| Atazanavir +/− ritonavir plus 2 NRTIs | 13 (27) |

| NNRTI plus 2 NRTIs | 6 (12.5) |

| NNRTI plus PI plus NRTI | 3 (6.3) |

| Darunavir/ritonavir containing regimen | 2 (4.2) |

| Other^ | 5 (10.4) |

| Adherence to currently prescribed cART, n (%) | |

| Yes | 25 (52.1) |

| No | 23 (47.9) |

Previous ARV exposure was defined as “treatment experienced” if the patient had been exposed to less than 2 previous cART regimens, and “extensively treatment experienced” if the patient had been exposed to 2 or more previous cART regimens.

Includes: dual boosted PIs plus 2 NRTIs (n=1), lopinavir/ritonavir plus 3 NRTIs (n=1), nelfinavir plus 2 NRTIs (n=1), enfuvirtide plus PI plus 2 NRTIs (n=1), unboosted fosamprenavir plus 2 NRTIs (n=1)

NOTE: ARV = antiretroviral, cART = combination antiretroviral therapy, IQR = interquartile range, NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PI = protease inhibitor

The most commonly identified ARV-related issues included suboptimal regimen based on RAMs at baseline (35.4%), stavudine-containing regimens (18.8%), lopinavir/ritonavir or fosamprenavir-containing regimens (14.6%), and significant drug-drug interactions (10.4%) (Table 2). The most common types of interventions recommended by the AST included regimen optimization in patients on suboptimal regimens based on resistance mutations (35.4%), switching to safer ARVs (33.3%), and averting significant drug-drug interactions (10.4%). The rates of implementation in each category of intervention are summarized in Table 2. By July 1, 2014, 35 of 48 (73%) recommendations made by the AST were implemented, and 21 of these 35 (60%) were implemented within 6 months of ARV review (Figure 2). The median (IQR) time to implementation of recommendations was 134 (28-322) days.

Table 2.

Summary of identified antiretroviral-related issues, types of interventions recommended by antiretroviral stewardship team, and frequency of implementation

| Identified ARV-related issues (n=48) | Type of intervention recommended | Proportion of interventions implemented in each category, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal regimen based on resistance mutations at baseline (n=17) | Regimen optimization | 12 (70.6) |

| Stavudine-containing regimen (n=8) | Switch to safer NRTI | 5 (62.5) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir or fosamprenavir containing-regimen* (n=5) | Switch to safer PI | 3 (60) |

| Significant drug-drug interaction^ (n=5) | Alternative regimen to avoid drug-drug interaction | 5 (100) |

| Regimen simplification (n=4) | Regimen simplification | 2 (50) |

| Hypercholesterolemia on lopinavir/ritonavir (n=2) | Switch to more lipid friendly PI | 2 (100) |

| Dual-boosted PI-based regimen (n=1) | Regimen optimization | 1 (100) |

| Concern for potential non-adherence on NNRTI-based regimen (n=1) | Switch from NNRTI to PI-based regimen | 1 (100) |

| Concern for lack of CD4 gains despite virologic suppression (n=1) | Continue current regimen | 1 (100) |

| Concern for facial atrophy on stavudine (n=1) | Switch from stavudine to safer NRTI | 1 (100) |

| Switch from pill to liquid (n=1) | Switch from pills to liquid | 1 (100) |

| Switch from once daily to twice daily based on patient's preference (n=1) | Regimen optimization | 1 (100) |

| Wrong dose of ARV prescribed (n=1) | Change in dose of ARV | 0 (0) |

Patients on lopinavir/ritonavir or fosamprenavir containing regimens were between the ages of 9 and 22 years, and could have been switched to newer, safer PIs

Included various acid suppressants with atazanavir, tenofovir with unboosted atazanavir, and inhaled corticosteroids (fluticasone) with PIs

NOTE: ARV = antiretroviral, NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, PI = protease inhibitor

Outcomes

The primary outcome of change in CD4 count and VL by 6 and 12 months was assessed in 28 patients in whom a change in CD4 and/or VL was anticipated as a result of the recommendations made by the AST. There were 10 patients included in the primary outcomes analysis who had recommendations implemented within 6 months of ARV review, and 18 patients included who did not have recommendations implemented within 6 months (Figure 2). There were no differences between the two groups with respect to age, HIV acquisition, previous ARV exposure, baseline CD4 count, baseline VL, presence of RT or PR RAMs, or baseline adherence (data not shown).

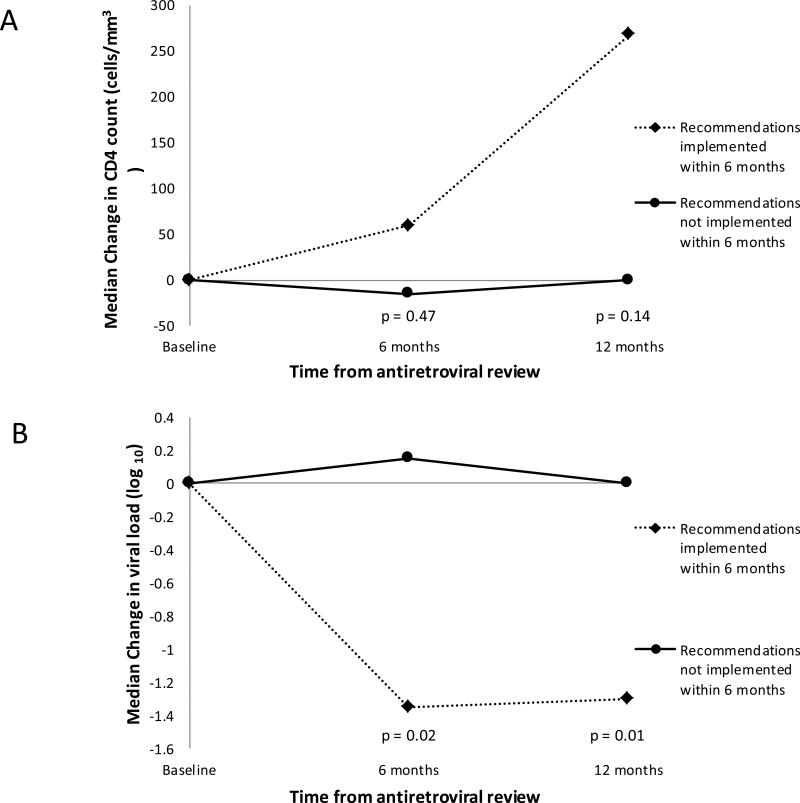

At 6 months, there was no significant difference in change in CD4 count between those with recommendations implemented within 6 months vs. not [median (IQR) change was 59.5 (−22 to 185) vs. −15 (−84 to 166.5) cells/mm3, p 0.47] (Figure 3). By 12 months, there was a trend towards better CD4 improvements if recommendations were implemented within 6 months [268.5 (11 to 401) vs. 0 (−39 to 64) cells/mm3, respectively, p 0.14].

Figure 3.

Change in CD4 count (Panel A) and viral load (Panel B) at 6 and 12 months post-antiretroviral review for 28 patients in which improvement in CD4 count and/or viral load was anticipated as a result of the recommendations made by the antiretroviral stewardship team

For median change in VL (log10), there was a significant benefit seen at 6 months in those with recommendations implemented by 6 months [−1.32 (−2 to 0) vs. 0.12 (−0.56 to 0.64) log10, respectively, p 0.02]. Similarly at 12 months, there was a significant benefit seen in median change in VL (log10) in those with recommendations implemented by 6 months [−1.3 (−2 to −1) vs. 0 (−0.11 to 0.21) log10, respectively, p 0.01]. Additionally, higher proportions of patients with recommendations implemented by 6 months achieved a change in VL of at least −0.7 log10 at 6 and 12 months after ARV review (70% vs. 25%, respectively, at 6 months (p 0.04), and 83.3% vs. 7.14%, respectively, at 12 months (p = 0.001).

The odds of achieving the outcome of change in VL of at least −0.7 log10 at 6 months was an unadjusted OR of 7 (95% CI 1.07 to 45.9, p 0.043) when recommendations were implemented by 6 months. After adjusting for baseline adherence, the adjusted OR at 6 months was 6.8 (95% CI 1.03 to 44.9, p <0.05). The unadjusted OR of achieving a change in VL of at least −0.7 log10 at 12 months was 65 (95% CI 3.38 to 1251, p 0.006) when recommendations were implemented by 6 months. Due to the small sample size, an adjusted OR at 12 months could not be calculated.

In terms of secondary outcomes, amongst patients with actual side effects due to ARVs (n=3), 2 had hypercholesterolemia on lopinavir/ritonavir, both were switched to the more lipid friendly boosted atazanavir, and both had decreases in lipids at 6 and 12 months after the switch. One patient had facial lipoatrophy on stavudine, which was switched to a safer NRTI, and no further progression of lipoatrophy was observed at 6 and 12 months. Five patients had significant drug-drug interactions including various acid suppressants with atazanavir, tenofovir with unboosted atazanavir, and fluticasone with PIs. All five patients had regimen changes implemented that averted the interaction.

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge that demonstrates that an ARV stewardship program implemented in an outpatient pediatric HIV clinic can improve clinical outcomes. We identified a significant benefit in virologic outcomes at 6 and 12 months when recommendations were implemented within 6 months of ARV review. Patients who had recommendations implemented within 6 months had a 7-fold higher probability of achieving a 0.7 log10 reduction in VL by 6 months, and this benefit remained significant after controlling for adherence. Our findings demonstrate that even in a highly specialized pediatric HIV clinic with experienced prescribers, suboptimal regimens and medication errors can still occur contributing to loss of virologic control, and the implementation of a systematic ARV stewardship program resulted in significantly improved clinical outcomes.

Previous studies conducted in adult HIV-infected inpatients have demonstrated that medication reconciliation and profile review conducted by an HIV or infectious diseases trained pharmacist can significantly reduce medication errors9-18. In the adult outpatient HIV clinic setting, many studies have demonstrated positive outcomes of various interventions19-25, some included interventions involving assessment of appropriateness of ARV regimens based on resistance testing21,24, and some have demonstrated improvement in CD4 gains and VL suppression21,22,24. In our study conducted in the pediatric population, the majority of interventions made by the AST were related to regimen optimization due to genotypic resistance, switching to safer ARVs, and averting significant drug-drug interactions. Similar to adult studies, we demonstrated that the implementation of our systematic AST had a positive impact on clinical outcomes, particularly VL reduction.

In our study, the implementation rate of recommendations made by the AST was 73%, which is lower compared to previous studies in adults where 100% of recommendations were implemented21,24. Only 60% of recommendations implemented were within 6 months of ARV review. The median time to implementation was ~4.5 months, which was longer than desired especially for recommendations that involved regimen optimization. From discussions at our weekly multidisciplinary meeting, we learned that a significant barrier to regimen optimization is the concern for preservation of future treatment options in a non-adherent population that has decades of cART ahead of them. In patients who are intermittently adherent, providers may defer regimen optimization while attempting to resolve adherence issues, which is regarded as an acceptable but not ideal interim strategy30. Oftentimes, therapy optimization requires complex regimens with increased pill burden that could further jeopardize adherence resulting in virologic failure, emergence of RAMs on the new regimen, and the inability to preserve drugs for future use. However, maintaining patients on failing regimens is not desirable as this may also increase the risk of selecting more RAMs, jeopardizing future treatment options. Therefore, the potential to initiate optimal therapy should be reassessed at every opportunity30.

Currently, there are no consensus guidelines for the implementation of ARV stewardship programs. The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for antimicrobial stewardship8 do not discuss the role of stewardship programs in the HIV population, and the Department of Health and Human Services guidelines for the management of HIV in pediatric30 and adolescent31 populations do not mention stewardship or other means of QI as a strategy to improve clinical outcomes of patients infected with HIV. Our study, and previous studies21,24 have shown that outpatient ARV stewardship programs can positively impact clinical outcomes. Therefore, we believe that ARV stewardship programs have significant value in this difficult to manage population where considerations for drug-drug interactions, dose adjustments, emergence of resistance, co-morbid conditions, significant toxicities, etc. make therapy selection challenging, particularly as our armamentarium of agents is a constantly expanding. Even in highly specialized HIV clinics such as our own, there was still room for improvement as ARV-related issues were identified in almost half of patients reviewed by the AST. We believe that our systematic approach to assessment, as outlined in Figure 1, can be applied in any clinical setting when evaluating appropriateness of cART in an HIV-infected patient.

There are limitations to our study, notably the small number of patients included in our primary outcomes analysis of change in CD4 and VL, which significantly limits our power to detect differences in outcomes. Another limitation is the high rate of non-adherence (~50%), however this rate is consistent with what is reported in the literature on non-adherence in the adolescent HIV-infected population in North America32. Additionally, our definition of non-adherence was categorical (yes or no) based on providers’ judgment, and not objectively measured in a systematic quantitative fashion. Although we controlled for adherence in our final model, baseline non-adherence could have biased providers to not implement recommendations made by the AST. Other limitations include the fact that this was a single center study, and although we believe that our systematic approach to cART assessment can be applied to any clinical setting, our results may not be generalizable to other clinic settings where resources for continuous systematic review may not be available, or the expertise of an HIV-trained pharmacist and/or physician is not available.

Measurement of quality of care and implementation of continuous QI programs to address gaps in care is advocated to improve clinical outcomes and successful therapy in HIV-infected individuals33. Previous publications of QI programs in outpatient HIV clinics have evaluated quality of care indicators such as achievement of VL suppression and shown that the implementation of a QI program has the potential to increase the proportion of patients achieving VL suppression34. Future steps for our ARV stewardship program will include identifying key quality measures to track longitudinally, and set goals for achievement for selected measures.

In conclusion, ARV stewardship is an effective strategy to improve clinical outcomes in pediatric patients infected with HIV, resulting in significant reductions in VL at 6 and 12 months when recommendations made by the AST were implemented within 6 months of review. In patients who are virologically suppressed, switching to safer and better-tolerated ARVs with fewer long-term side effects is also an important goal. In this heavily pre-treated cohort of pediatric patients harboring significant RAMs, there are many potential barriers to the achievement of VL suppression including non-adherence, ARV dosing/formulation availability, drug-drug interactions, side effects, and the need to preserve future treatment options. ARV stewardship is able to modify or attenuate many of these barriers, leading to improved clinical outcomes, and should be considered as a core strategy for continuous QI in the management of HIV-infected children and adolescents.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Intensive Primary Care (IPC) clinic team members for their contribution to the care of children and adolescent patients living with HIV, and for their openness and acceptance of our ARV stewardship program.

Allison L. Agwu: This work is supported by the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant [1K23 AI084549] to Dr. Allison L. Agwu, MD, ScM.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures:

Alice Hsu: none

Asha Neptune: none

Constants Adams: This work is supported by the James A. Ferguson Infectious Disease Fellowship awarded to Constants Adams.

Nancy Hutton: none

References

- 1.Agwu AL, Fairlie L. Antiretroviral treatment, management challenges and outcomes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16:18579. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laughton B, Cornell M, Boivin M, Van Rie A. Neurodevelopment in perinatally HIV-infected children: a concern for adolescence. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16:18603. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellins CA, Malee KM. Understanding the mental health of youth living with perinatal HIV infection: lessons learned and current challenges. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16:18593. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2011;25:413–22. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arshad S, Rothberg M, Rastegar DA, Spooner LM, Skiest D. Survey of physician knowledge regarding antiretroviral medications in hospitalized HIV-infected patients. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2009;12:1. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans-Jones JG, Cottle LE, Back DJ, et al. Recognition of risk for clinically significant drug interactions among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50:1419–21. doi: 10.1086/652149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li EH, Foisy MM. Antiretroviral and Medication Errors in Hospitalized HIV-Positive Patients. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2014;48:998–1010. doi: 10.1177/1060028014534195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007;44:159–77. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eginger KH, Yarborough LL, Inge LD, Basile SA, Floresca D, Aaronson PM. Medication errors in HIV-infected hospitalized patients: a pharmacist's impact. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2013;47:953–60. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels LM, Raasch RH, Corbett AH. Implementation of targeted interventions to decrease antiretroviral-related errors in hospitalized patients. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2012;69:422–30. doi: 10.2146/ajhp110172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtzman CW, Gallagher JC. Antiretroviral Medication Errors among Hospitalized HIV-Infected Adults. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;55:1585–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis721. author reply 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan MA, Atkinson KM, Sha BE, Crank CW. Evaluation of pharmacy-implemented medication reconciliation directed at antiretroviral therapy in hospitalized HIV/AIDS patients. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2010;44:222–3. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pastakia SD, Corbett AH, Raasch RH, Napravnik S, Correll TA. Frequency of HIV-related medication errors and associated risk factors in hospitalized patients. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2008;42:491–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heelon M, Skiest D, Tereso G, et al. Effect of a clinical pharmacist's interventions on duration of antiretroviral-related errors in hospitalized patients. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2007;64:2064–8. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garey KW, Teichner P. Pharmacist intervention program for hospitalized patients with HIV infection. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2000;57:2283–4. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.24.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders J, Pallotta A, Bauer S, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship program to reduce antiretroviral medication errors in hospitalized patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Infection control and hospital epidemiology : the official journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America. 2014;35:272–7. doi: 10.1086/675287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carcelero E, Tuset M, Martin M, et al. Evaluation of antiretroviral-related errors and interventions by the clinical pharmacist in hospitalized HIV-infected patients. HIV medicine. 2011;12:494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yehia BR, Mehta JM, Ciuffetelli D, et al. Antiretroviral medication errors remain high but are quickly corrected among hospitalized HIV-infected adults. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;55:593–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Maat MM, de Boer A, Koks CH, et al. Evaluation of clinical pharmacist interventions on drug interactions in outpatient pharmaceutical HIV-care. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2004;29:121–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2003.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geletko SM, Poulakos MN. Pharmaceutical services in an HIV clinic. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2002;59:709–13. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.8.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.March K, Mak M, Louie SG. Effects of pharmacists' interventions on patient outcomes in an HIV primary care clinic. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2007;64:2574–8. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, Kinsman CJ, Quesenberry CP. Effect of clinical pharmacists on utilization of and clinical response to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2007;44:531–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318031d7cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsch JD, Rosenquist A, Best BM, Miller TA, Gilmer TP. Evaluation of the first year of a pilot program in community pharmacy: HIV/AIDS medication therapy management for Medi-Cal beneficiaries. Journal of managed care pharmacy : JMCP. 2009;15:32–41. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma A, Chen DM, Chau FM, Saberi P. Improving adherence and clinical outcomes through an HIV pharmacist's interventions. AIDS care. 2010;22:1189–94. doi: 10.1080/09540121003668102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch JD, Gonzales M, Rosenquist A, Miller TA, Gilmer TP, Best BM. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDS. Journal of managed care pharmacy : JMCP. 2011;17:213–23. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: December 2010. Topics in HIV medicine : a publication of the International AIDS Society, USA. 2010;18:156–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson VA, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, et al. 2011 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2011;19:156–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson VA, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: March 2013. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2013;21:6–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wensing AM, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, et al. 2014 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2014;22:642–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. [9/21/14];Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/pediatricguidelines.pdf.

- 31.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; [9/21/14]. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH, Gerver SM, Fidler S, Ward H. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in adolescents living with HIV: systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2014 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horberg MA, Aberg JA, Cheever LW, Renner P, O'Brien Kaleba E, Asch SM. Development of national and multiagency HIV care quality measures. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51:732–8. doi: 10.1086/655893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landon BE, Wilson IB, McInnes K, et al. Effects of a quality improvement collaborative on the outcome of care of patients with HIV infection: the EQHIV study. Annals of internal medicine. 2004;140:887–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]