Abstract

Background

Little is known on the risk of cancer in HIV-positive children in sub-Saharan Africa. We examined incidence and risk factors of AIDS-defining and other cancers in pediatric antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs in South Africa.

Methods

We linked the records of five ART programs in Johannesburg and Cape Town to those of pediatric oncology units, based on name and surname, date of birth, folder and civil identification numbers. We calculated incidence rates and obtained hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from Cox regression models including ART, sex, age, and degree of immunodeficiency. Missing CD4 counts and CD4% were multiply imputed. Immunodeficiency was defined according to World Health Organization 2005 criteria.

Results

Data of 11,707 HIV-positive children were included in the analysis. During 29,348 person-years of follow-up 24 cancers were diagnosed, for an incidence rate of 82 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 55-122). The most frequent cancers were Kaposi Sarcoma (34 per 100,000 person-years) and Non Hodgkin Lymphoma (31 per 100,000 person-years). The incidence of non AIDS-defining malignancies was 17 per 100,000. The risk of developing cancer was lower on ART (HR 0.29, 95%CI 0.09–0.86), and increased with age at enrolment (>10 versus <3 years: HR 7.3, 95% CI 2.2-24.6) and immunodeficiency at enrolment (advanced/severe versus no/mild: HR 3.5, 95%CI 1.1-12.0). The HR for the effect of ART from complete case analysis was similar but ceased to be statistically significant (p=0.078).

Conclusions

Early HIV diagnosis and linkage to care, with start of ART before advanced immunodeficiency develops, may substantially reduce the burden of cancer in HIV-positive children in South Africa and elsewhere.

Keywords: cancer epidemiology, HIV/IADS, cohort study, record linkage

INTRODUCTION

South Africa is one of the countries most heavily affected by the HIV epidemic. An estimated 6.3 million people were living with HIV in South Africa in 2013, including 360,000 children.1 HIV-positive children are at higher risk of developing cancer than children from the general population 2-4 or HIV-negative children.5-8 Studies from Europe and the United States of America (USA) have shown that the incidence of cancer has declined as combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has become more widely available.3, 4, 9 Cohort studies of HIV-positive children are rare in the African region, and no study has so far assessed the impact of ART on the risk of developing cancer.10 Moreover, data collection is often restricted to AIDS-defining cancers, i.e. Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) in these cohorts.11 Even the data on AIDS-defining cancers may be incomplete, since cohorts are based in ART programs but cancers are treated in pediatric oncology units. Record linkages with cancer registries can overcome these limitations but to date only one record linkage study from the pre-ART era reported the incidence rate of cancer in HIV-positive children in an African setting.12 Lastly, it may be difficult to estimate incidence and risk factors with precision because the number of HIV-positive children followed-up in any single cohort is typically small.

We did a record linkage study that combined data from five HIV cohort studies that participate in the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) with the records of the four referral pediatric oncology units in South Africa. We aimed to define the incidence rate, risk factors and the impact of ART on the development of AIDS-defining and non AIDS-defining cancers in HIV-positive children who attended antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs in South Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

IeDEA is a research consortium established in 2006 to inform the scale-up of ART through clinical and epidemiological research.11, 13-15 The four African regions of IeDEA have been described in detail elsewhere.11 In this study, we included five South African treatment programs that provide care for HIV-positive children: the Khayelitsha Township ART program, the Tygerberg Hospital program and the Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital program in Cape Town; and the Harriet Shezi and Rahima Moosa programs in Johannesburg.16 All five programs follow the guidelines of the South African National Department of Health17,18 and have approval from their local ethics committee to provide data to IeDEA. Data are collected in the context of routine care at baseline and each follow-up visit, including socio-demographic data, the date of starting ART, type of treatment initiated, and CD4 measurements and HIV-1 plasma RNA levels.11 The clinical and laboratory data are converted into a standardized format, the HIV Cohorts Data Exchange Protocol (HICDEP) and transferred to the IeDEA coordinating centers at the Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research (CIDER), University of Cape Town, South Africa and the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of Bern, Switzerland. The median date of the last follow up was August 19th 2010 (interquartile range 8 July 2008 to 2 June 2011).

Record linkage

HIV cohort data were linked with the records of four academic pediatric oncology referral units:19 the Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and the Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town; and the Chris Hani Baragwanath and Charlotte Maxeke hospitals in Johannesburg. We included all HIV-positive children, aged 16 years or younger at enrolment, followed up at one of the five ART programs, and all patients with a confirmed cancer diagnosis and documented HIV-positive followed up at one of the four oncology units. We linked records probabilistically using the record linkage software G-Link of Statistics Canada,20 based on folder numbers, South African civil identification numbers, date of birth, sex, name and surname, ethnicity, date of death, and date of cancer diagnoses. Based on probability weights, possible matches were identified and confirmed or rejected after review. For each definite match, we retrieved data on the cancer diagnosis, including type, histology, date of diagnosis, stage and location and treatment. This information was anonymized and then incorporated into the IeDEA database.

Definitions

We defined the CD4 cell measurement at enrolment as the measurement closest to the enrolment date, within a window of 180 days before and 30 days after enrolment. We defined the CD4 measurement at start of ART as the measurement closest to the start of ART date, within a window of 180 days before and 30 days after ART was started. The degree of immunodeficiency (none, mild, advanced, severe) was defined using the WHO 2005 surveillance definition for the African region.21

We defined ART as a regimen of at least three antiretroviral drugs from at least two drug classes, including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. The calendar year of enrolment was categorized as before 2005 or thereafter. Calendar year of starting ART was categorized as before 2005, 2005 to 2009 and 2010 onwards to reflect the scale up of ART in 2005 and changes in the South African ART guidelines in 2010.17,18 Prevalent cases were defined as cancers diagnosed before or at enrolment into the cohort. Incident cases were defined as cancers diagnosed during follow-up.

Statistical methods

In children not on ART, we measured time from the date of enrolment to the earliest of the date of diagnosis, start of ART, last follow-up visit or death. In children on ART, we measured time from the start of ART to the earliest of the date of the cancer diagnosis, last follow-up visit, or death. In children who were ART naïve at enrolment and who started ART during follow-up, we split the follow-up time so that they contributed time both to the not-on-ART and the on-ART analysis. We took an intent-to-continue-treatment approach and ignored changes to ART regimens, including interruptions and terminations. Incidence rates were calculated by dividing the number of children who developed cancer by the number of person-years at risk, with Poisson 95% confidence intervals (CI). We examined risk factors for incident cancer in Cox proportional hazard models stratified by cohort. Multivariable models were adjusted for time-updated ART, age at enrolment, sex, and degree of immunodeficiency (none, mild, advanced, severe) at enrolment. Missing CD4 counts and CD4% were multiply imputed using predictive mean matching and chained equations stratified by gender and age. In sensitivity analyses we restricted the analysis to the complete data and excluded patients with missing data.

Results are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), incidence rates per 100,000 person-years, Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative incidence and crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs), with 95% CI. Stata version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

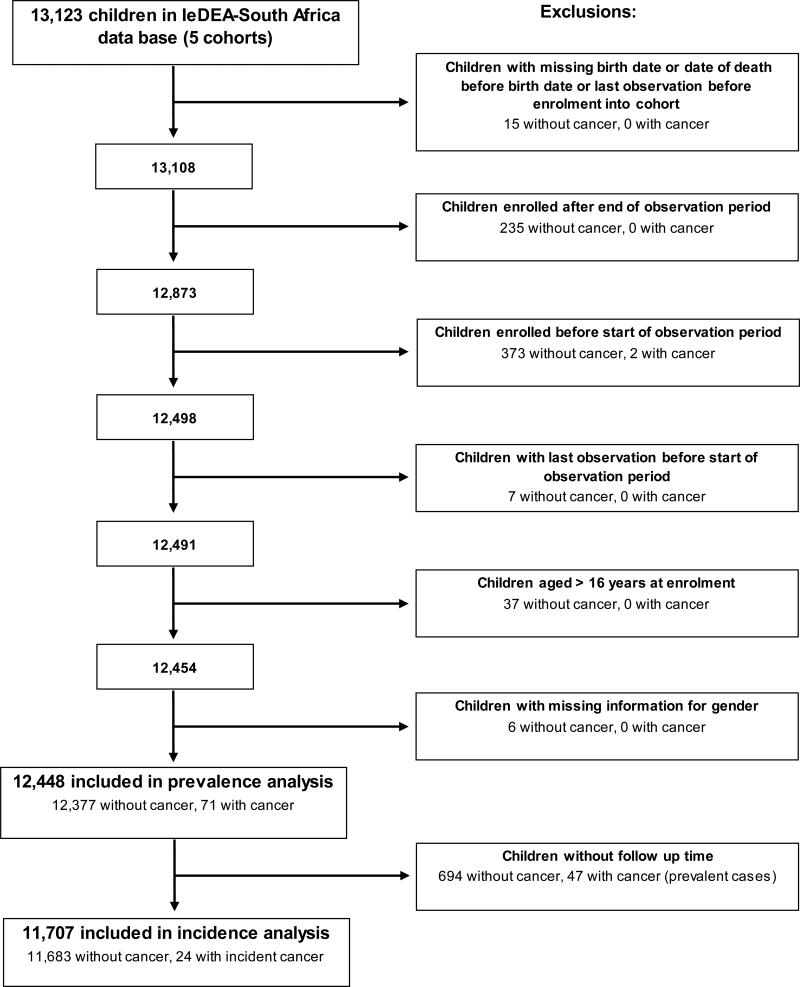

The five ART cohorts included 12,448 eligible children (Table 1, Figure 1). Almost half of children (5,810, 47%) were from the Harriet Shezi ART program in Johannesburg. Most children (10,529, 85%) were enrolled in 2005 or later, at a time when ART was scaled up in South Africa. The majority of children (8,764, 70%) started ART at or after enrolment. CD4 cell measurements at enrolment were available for 7,995 (64%) children. Of these children, 5,333 (67%) presented with advanced or severe immunodeficiency (Table 1). The median CD4 cell count at enrolment was 493 cells/μL (IQR 216-922), the median CD4% was 15% (IQR 9%-23%). Among children with missing CD4 cell measurements, the imputed median CD4 cell count was 664 cells/μL (IQR 396-906) and the imputed median CD4% was 16% (IQR 13%-19%) at enrolment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-positive children with prevalent and incident cancer in South Africa.

| Children with cancer | Children free from cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalent cases | Incident cases | |||

| All patients | 47 | 24 | 12,377 | |

| Cohort | Harriet Shezi | 18 (38%) | 7 (32%) | 5,785 (46%) |

| Khayelitsha | 2 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1,096 (9%) | |

| Rahima | 1 (2%) | 3 (16%) | 2,752 (23%) | |

| Red Cross | 20 (42%) | 6 (24%) | 1,664 (13%) | |

| Tygerberg | 6 (15%) | 7 (24%) | 1,080 (9%) | |

| Gender | Male | 36 (77%) | 14 (52%) | 6,224 (50%) |

| Female | 11 (23%) | 10 (48%) | 6,153 (50%) | |

| Age at enrolment | Median (IQR) | 6.6 (4.3 – 9.9) | 5.0 (2.5 – 9.0) | 2.5 (0.7 – 6.3) |

| Age at enrolment | ≤ 1 year | 1 (2%) | 2 (8%) | 3,879 (31%) |

| 1 to < 3 years | 3 (6%) | 5 (21%) | 2,857 (23%) | |

| 3 to < 5 years | 12 (26%) | 5 (21%) | 1,574 (13%) | |

| 5 to < 10 | 20 (43%) | 7 (30%) | 2,897 (23%) | |

| ≥ 10 years | 11 (23%) | 5 (21%) | 1,170 (10%) | |

| Immunodeficiency at enrolment* | No / mild | 6 (13%) | 2 (8%) | 2,654 (21%) |

| Advanced / severe | 9 (20%) | 9 (38%) | 5,315 (43%) | |

| Missing | 32 (68%) | 13 (54%) | 4,408 (36%) | |

| Starting ART | Before enrolment | 19 (40%) | 2 (8%) | 1,924 (16%) |

| At or after enrolment | 27 (57%) | 20 (83%) | 8,717 (70%) | |

| Never starting | 1 (2%) | 2 (8%) | 1,713 (14%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 23 (0.2%) | |

| Calendar year of starting ART | Before 2005 | 11 (23%) | 9 (38%) | 1,213 (10%) |

| ≥ 2005 to | 31(66%) | 12 (50%) | 7,628 (62%) | |

| ≥ 2010 | 4 (9%) | 1 (4%) | 1,800 (15%) | |

| Never starting | 1 (2%) | 2 (8%) | 1,713 (14%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 23 (0.2%) | |

| Calendar year of enrolment | Before 2005 | 10 (21%) | 10 (42%) | 1,899 (15%) |

| ≥ 2005 | 37 (79%) | 14 (58%) | 10,478 (85%) | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy

WHO 2005 surveillance definition of immunodeficiency for the African region:21 No significant immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months >35 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months >25 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count > 500/mm3; Mild immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months 25-34 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months 20-24 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count 350-499/mm3; Advanced immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months 20-24 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months 15-19 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count 200-349/mm3; Severe immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months <20 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months < 15 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count < 200/mm3.

Figure 1.

Identification of study population for analysis of antiretroviral therapy and cancer in HIV-infected children in South Africa.

The flow diagram shows the number of included and excluded patients.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IeDEA, International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS

We identified a total of 71 eligible children with cancer: 49 (69%) were identified in the records of the oncology departments, 11 children (15%) were recorded with cancer in the ART programs, and 11 children (15%) were recorded in both data sets. Forty-seven children presented with cancer before or at enrolment, for a prevalence of 0.38% (95% CI 0.28-0.50), and 24 children developed cancer during follow-up. Children who presented with cancer or developed cancer later on were older at enrolment than children free of cancer: the median age at enrolment was 6.6 years and 5.0 years in children with prevalent and incident cancer, respectively, and 2.5 years in children not developing cancer. Children who developed cancer during follow-up were more likely to have experienced advanced or severe immunodeficiency than children who did not develop cancer (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients with prevalent and incident cancer at the time of cancer diagnosis. Fifty-one percent of children presented with advanced or severe immunodeficiency at the time of cancer diagnosis; in 42% of children the CD4 measurements were missing. In children with available data the median CD4 cell count at diagnosis was 372 cells/μL (IQR 171-762) in children with prevalent cancer, and 599 cells/μL (IQR 62-978) in children with incident cancer. Most cancers were AIDS-defining, including 21 prevalent and 10 incident cases of KS, and 20 prevalent and 9 incident cases of NHL. Non AIDS-defining cancers included acute leukemias, Hodgkin lymphoma, nephroblastoma and leiomyosarcoma. Ninety percent of all cancers (64/71) were associated with Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) or HHV-8 co-infections (Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma and leiomyosarcoma).

Table 2.

Characteristics at the time of cancer diagnosis of HIV-positive children with prevalent and incident cancer in South Africa.

| Children diagnosed with cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalent cases | Incident cases | ||

| All patients | 47 | 24 | |

| Age at cancer diagnosis | Median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.7 – 9.7) | 6.3 (3.8 – 10.2) |

| Age at cancer diagnosis | ≤ 1 year | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) |

| 1 to <3 years | 6 (13%) | 3 (13%) | |

| 3 to <5 years | 12 (26%) | 3 (13%) | |

| 5 to <10 years | 18 (38%) | 11 (46%) | |

| ≥ 10 years | 10 (21%) | 6 (25%) | |

| CD4 cell count at cancer diagnosis* | Median, IQR | 372 (171 – 762) | 599 (62 – 978) |

| Immunodeficiency at cancer diagnosis** | No / mild | 3 (6%) | 2 (8%) |

| Advanced / severe | 24 (51%) | 12 (50%) | |

| Missing | 20 (43%) | 10 (42%) | |

| ART history | Not on ART | 43 (91%) | 12 (50%) |

| On ART | 4 (8%) | 12 (50%) | |

| Type of cancer | HHV-8 associated, KS | 21 (45%) | 10 (42%) |

| EBV associated | 23 (49%) | 10 (42%) | |

| NHL, Burkitt | 9 (19%) | 3 (13%) | |

| NHL, non Burkitt | 10 (21%) | 6 (25%) | |

| NHL, CNS lymphoma | 1 (2%) | 0 | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 3 (6%) | 0 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 0 | 1 (4%) | |

| ALL, AML | 0 | 4 (17%) | |

| Other*** | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; HHV-8, human herpes virus 8; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; NHL, non Hodgkin lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia

Based on 27 children with prevalent cancer and available CD4 count at cancer diagnosis, and 14 children with incident cancer and available CD4 count at cancer diagnosis.

WHO 2005 surveillance definition of immunodeficiency for the African region:21 No significant immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months >35 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months >25 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count > 500/mm3; Mild immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months 25-34 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months 20-24 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count 350-499/mm3; Advanced immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months 20-24 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months 15-19 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count 200-349/mm3; Severe immunosuppression: children up to age 12 months <20 CD4%; children 13 – 59 months < 15 CD4%; children ≥ 5 years CD4 cell count < 200/mm3.

Other: nephroblastoma, for two cases histology not provided

Cancer incidence and risk factors for developing cancer

The analyses of incidence were based on 11,707 children, of whom 24 developed cancer during 29348 person-years (Figure 1). The median observation time was 2.0 years (IQR 6 months-4.0 years). In the 24 children with incident cancer, the median time from enrolment into ART program to cancer diagnosis was 46 days (IQR 15-287). At the time of analysis, 6401 children (55%) were alive and under follow-up, 805 (7%) had died, 3,976 (34%) had been transferred to a different clinic, and 525 (4%) were lost to follow-up. In children on ART, the cancer incidence rate was 50/100,000 person-years (95% CI 29-89); in children not on ART, the rate was 220/100,000 person-years (95% CI 125-387) (Table 3). The incidence of AIDS-defining cancers was 65/100,000, with an incidence rate of 34/100,000 for KS, and 31/100,000 for NHL. The incidence of non AIDS-defining cancers was 17/100,000 person-years. The rate of cancer typically associated with EBV infection (NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma) was 34/100,000 person-years.

Table 3.

Incidence rates of cancer per 100,000 person-years in HIV-positive children in South Africa.

| Person-years at risk | No. of cancer cases | Incidence rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any cancer | 29,348 | 24 | 82 (55 – 122) |

| AIDS defining cancer | |||

| Any | 29,360 | 19 | 65 (41 – 102) |

| KS | 29,373 | 10 | 34 (18 – 63) |

| NHL | 29,393 | 9 | 31 (16 – 59) |

| Non AIDS defining cancer | 29,393 | 5 | 17 (7 – 41) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 14,919 | 14 | 94 (56 – 158) |

| Female | 14,425 | 10 | 70 (37 – 129) |

| Age at enrolment | |||

| ≤ 1 year | 6,343 | 2 | 32 (8 – 126) |

| 1 to <3 years | 7,362 | 5 | 68 (28 – 163) |

| 3 to <5 years | 4,908 | 5 | 102 (42 – 245) |

| 5 to <10 years | 8,197 | 7 | 85 (41 – 179) |

| ≥ 10 years | 2,534 | 5 | 197 (82 – 474) |

| Immunodeficiency at enrolment | |||

| No / mild | 6,282 | 2 | 32 (8 –127) |

| Advanced / severe | 12,395 | 9 | 73 (38 – 140) |

| Missing | 10,666 | 13 | 122 (71 -210) |

| ART treatment (time updated) | |||

| Not on ART | 5,464 | 12 | 220 (125 – 387) |

| On ART | 23,864 | 12 | 50 (29 – 89) |

| Missing, unclear | 16 | 0 | - |

| Calendar year of starting ART | |||

| Before 2005 | 5,197 | 9 | 173 (90 – 333) |

| ≥ 2005 to 2009 | 20,627 | 12 | 58 (33 – 102) |

| ≥ 2010 | 1,822 | 1 | 55 (8 – 390) |

| Missing / never starting | 1,697 | 2 | 118 (30 – 471) |

| Calendar year of enrolment | |||

| < 2005 | 9,012 | 10 | 111 (60 – 206) |

| ≥ 2005 | 20,331 | 14 | 69 (41 – 116) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; KS, Kaposi Sarcoma; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4 presents the results from univariable and multivariable Cox models from the main analysis based on imputed CD4 data and the sensitivity analysis based on complete cases. The multivariable models were adjusted for immunodeficiency, age at enrolment, gender and time-updated ART use.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios of developing cancer among HIV-positive children in South Africa

| Analysis based on imputed data (n=11,689) |

Complete case analysis (n=7,646) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable* | Univariable | Multivariable* | ||

| ART treatment (time updated) | Not on ART | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| On ART | 0.43 (0.15-1.22) | 0.29 (0.09-0.86) | 0.23 (0.04-1.20) | 0.23 (0.04-1.18) | |

| Gender | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.74 (0.33-1.67) | 0.69 (0.30-1.56) | 0.88 (0.27-2.89) | 0.86 (0.26-2.85) | |

| Age at enrolment into ART program [years] | < 3 years | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 to < 5 years | 3.69 (1.15 – 11.84) | 3.41 (1.06 – 10.97) | 7.77 (1.27 – 47.34) | 6.60 (1.08 – 40.44) | |

| 5 to < 10 years | 2.75 (0.95 – 7.97) | 2.89 (1.00 – 8.36) | 5.67 (1.01 – 31.81) | 5.76 (1.02 – 32.46) | |

| ≥ 10 years | 7.05 (2.11 – 23.53) | 7.33 (2.19 – 24.57) | 8.41 (1.11 – 63.42) | 8.29 (1.10 – 62.41) | |

| Immunodeficiency at enrolment | No / mild | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Advanced / severe | 2.59 (0.89 – 7.57) | 3.54 (1.05 – 11.97) | 1.87 (0.40 – 8.72) | 2.22 (0.45 – 10.87) | |

| Calendar year of starting ART | Before 2005 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| ≥ 2005 to 2009 | 0.45 (0.17 – 1.17) | - | 0.45 (0.17 – 1.17) | - | |

| ≥ 2010 | 0.26 (0.03 – 2.27) | - | 0.26 (0.03 – 2.27) | - | |

| Calendar year of enrolment | Before 2005 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| ≥ 2005 | 0.55 (0.22 – 1.35) | - | 0.58 (0.15 – 2.84) | - | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval.

All models were stratified by cohort.

Adjusted for time-updated ART, gender, age at enrolment and immunodeficiency at enrolment.

Definition of immunodeficiency at enrolment into cohort according to WHO 2005 surveillance definition.

In the main analysis the multivariable model showed that children on ART had a lower risk of developing cancer than children not on ART (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.09-0.86). Children with severe or advanced immunodeficiency at enrolment were more likely to develop cancer than children with mild or no immunodeficiency (HR 3.54, 95% CI 1.05-11.79). The risk of developing cancer increased with age at enrolment (HR children aged >10 years versus aged <3 years 7.33, 95% CI 2.19-24.57). The hazard ratios from the univariable model were similar but tended to have wider confidence intervals. The effect of ART on the risk of cancer was less pronounced and failed to reach statistical significance (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.15-1.22). The hazard ratios from the analyses based on complete cases were similar to the analysis using multiply imputed data but the effect of ART on the risk of developing cancer was not statistically significant in this model (HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.04-1.18, Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that HIV-positive children in South Africa were at high risk of developing cancer with an overall incidence rate of 82/100,000 person-years. The majority of cancers were AIDS-defining with an incidence rate of 34/100,000 person-years for KS and 31/100,000 person-years for NHL. There were few non AIDS-defining malignancies with an incidence rate of 17/100,000 person-years. Children on ART had a substantially lower risk of developing cancer than children not on ART in multivariable analyses based on imputing data (HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.09-0.86). In complete case analysis the effect of ART was similar but not statistically significant. In all analyses the risk of developing cancer increased with age at enrolment.

This is the first study to describe the incidence rate of AIDS-defining and non AIDS-defining cancer and to estimate the impact of ART on the risk of developing cancer in HIV-positive children in South Africa. We used record linkage to identify both AIDS-defining and non AIDS-defining cancer cases, which are often not recorded, or only incompletely recorded in the data of HIV care and treatment programs. However, we may have missed cancer cases in children who were lost to follow-up or who sought treatment in other clinics. We identified only 24 incident cancer cases, and this limited our ability to conduct analyses stratified for different cancer types. Measurements of CD4 cell counts and percentages, HIV RNA loads, weight and height at enrolment into cohort were missing for a substantial proportion of patients. To overcome this limitation we used multiple imputation methods to impute missing CD4 cell measurements. This is a relatively young cohort (median age 2.5 years) most likely due to inclusion of many secondary and tertiary care sites where younger children and infants tend to be started on treatment. Given that we showed a strong association between older age and incident malignancy, the burden of malignancy may be higher in cohorts of older children. Median time between enrolment and cancer diagnosis was short and we cannot exclude that some of the cancers classified as incident cancer were actually prevalent cancers which had not been diagnosed before enrolment.

Our study showed a cancer incidence rate of 69/100,000 person-years in HIV-positive children in the ART era (2005 or later), which is substantially higher than the Globocan 2012 cancer incidence rates in children aged < 14 years in South Africa (5/100,000 person-years), Europe (13/100,000 person-years), and the US (16/100,000 person-years).22 Our incidence rates are lower than estimates from previous studies done in HIV-positive children in Europe and the US, see Table 5.3, 4, 9 It is difficult to directly compare studies because of different study designs, settings and populations. The US AIDS cancer match study2, 4 only included children diagnosed with AIDS, while the Italian HIV Registry9, 23 and our study also included children with HIV that had not yet progressed to AIDS. The Italian HIV Registry study was predominantly based on children aged under one year 9 whereas the median age at enrolment was 2.5 years in our study and 6.3 years for the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) study.3 The PACTG study relied on reporting of cancer within the cohort3 whereas our and other studies included additional cases identified through record linkage with cancer registries.2, 4 The definition of incident, as opposed to prevalent cancer case also differed across studies. The US AIDS cancer match study considered incident cancer cases to be those diagnosed three months after AIDS onset,2, 4 but in our and other studies, any cancer recorded immediately after enrolment into cohort or registry was classified as an incident cancer.3, 9, 23 More than 70% of all cancer cases identified in HIV-positive children in Europe and the US were EBV-associated cancer (i.e. NHL and leiomyosarcoma) while HHV-8 associated KS accounted for less than 8%.3, 9 In contrast, in this South African study 46% of cancers were cancers that are typically associated with EBV, while 44% of all cancers were KS, which is typically associated with HHV-8.

Table 5.

Literature review: cancer incidence in HIV-positive children in low, middle and high income countries

| Study | Country | Children included | Cancer cases identified | Cancer incidence rate per 100,000 pys (95% CI) | % reduction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| before ART era | during ART era | |||||

| British Paediatric Association Surveillance Unit31 | UK | 307 | 11 (7 NHL) |

1989-1995 NHL: 1,420 |

NA | NA |

| AIDS Cancer Match Study2 | USA | 4,954 | 124* (36 incident in post AIDS period 4 – 27 | 1980-1995: 656 | NA | NA |

| AIDS Cancer Match Study4 | USA | 5,850 | 106* | 1980-1995: 550 | 1996-2007: 213 | 61% |

| Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group PACTG3 | USA | 2,969 | 37 (17 prevalent, 20 incident)** | 1993-1997: 201 (0–414) | 1998-2003: 139 (74–238) | 31% |

| Italian Register HIV Infection in Children23 | Italy | 1,331 | 36 | 1985-1999: 418 (292–302) | NA | |

| Italian Register HIV Infection in Children9 | Italy | 1,190 | 35 | 1985-1995: 449 (237–664) |

1996-1999: 409 (168–650) 2000-2004: 76 (0–180) |

83% |

| Uganda Cancer Match Study12 | Uganda | 407 | 7, prevalent* 5, incident 2 (KS) | 1989-2002: 160 | NA | |

| IeDEA-SA | South Africa | 11,707 | Total 71, prevalent 47, incident 24** | 2000-2004: 111 (60–206) | 2005-2011: 69 (41–11) | 38% |

ADC AIDS-defining cancer; NADC non AIDS-defining cancer; KS Kaposi Sarcoma; NHL non Hodgkin Lymphoma; IeDEA-SA International Epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS in Southern Africa; pys person years; NA not available.

prevalent defined as: before or up to 3 months after AIDS, incident: later than 3 months after AIDS

prevalent defined as: before cohort enrolment, incident: after cohort enrolment

Despite these differences several of our results are in line with the findings of the previous studies. Children who received ART were at substantially lower risk of developing cancer than children not on ART. This finding is consistent with the results of studies from high income countries,3, 4, 9 see Table 5. Also, the risk of developing cancer tended to increase if immunodeficiency was more advanced at the time the child was enrolled into the cohort. This is in line with previous studies that showed that advanced stage HIV/AIDS disease,3, 9 or CD4 cell percentages below 15% (severely immunosuppressed), increased the risk of developing cancer.3

Many cancer cases reported in our study were prevalent and detected at the time of enrolment into the program. Children with prevalent cancer presented late to the ART programs, at older ages and with severe or advanced immunodeficiency. Many of the prevalent cancers might have been prevented if the child had been enrolled into an ART program earlier. Indeed, early detection of HIV-infection, linkage to care and ART treatment may be crucial for preventing development of cancer in HIV-positive children in South Africa.24-28 Since 2015 the World Health Organization guidelines recommend starting ART in all HIV-positive children regardless of age and immune status; 30 and South African guidelines recommend starting ART in children aged <5 years regardless of immune status and at CD4 cell counts <500 cells/μL in children aged >5 years.31 This recommendation should contribute to further reduce the risk of developing cancer in HIV-positive children. The reasons why children present late to ART programs need to be elucidated and uptake of ART increased. To better understand how best to prevent cancer in HIV-positive children in African settings we also need to investigate the impact of different first and second line ART regimens, and of different monitoring strategies (i.e. CD4 monitoring versus HIV viral load monitoring) on the risk of developing cancer.

In conclusion, our study linking data from HIV treatment and care programs with oncology clinic data suggests that early HIV diagnosis, linkage to care and start of ART before advanced immunodeficiency develops may substantially reduce the burden of cancer in HIV-positive children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U01AI069924, the National Cancer Institute (3U01AI069924-05S2), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, Cooperative Agreement AID 674-A-12-00029 for M.M.), Swiss Bridge Foundation, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Ambizione-PROSPER fellowship PZ00P3_136620_3 for J.B.). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government or of any other funding bodies. We thank Myriam Cevallos for her project management, Manuel Koller for his statistical support and Kali Tal for her editorial assistance.

This study was done on behalf of The International epidemiologic Database to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in Southern Africa Study Group. The study was funded by NIAID (grant number U01AI069924), NCI (grant number 5U01A1069924-05), the Swiss National Science Foundation (Ambizione-PROSPER PZ00P3_136620_3) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, Cooperative Agreement AID 674-A-12-00029).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests and sources of funding: No conflicts of interest declared.

IeDEA-SA Steering Group: Frank Tanser, Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of Kwazulu-Natal, Somkhele, South Africa; Christopher Hoffmann, Aurum Institute for Health Research, Johannesburg, South Africa; Benjamin Chi, Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia; Denise Naniche, Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça, Manhiça, Mozambique; Robin Wood, Desmond Tutu HIV Centre (Gugulethu and Masiphumelele clinics), Cape Town, South Africa; Kathryn Stinson, Khayelitsha ART Programme and Médecins Sans Frontières, Cape Town, South Africa; Geoffrey Fatti, Kheth'Impilo Programme, South Africa; Sam Phiri, Lighthouse Trust Clinic, Lilongwe, Malawi; Janet Giddy, McCord Hospital, Durban, South Africa; Cleophas Chimbetete, Newlands Clinic, Harare, Zimbabwe; Kennedy Malisita, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi; Brian Eley, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa; Michael Hobbins, SolidarMed SMART Programme, Pemba Region, Mozambique; Kamelia Kamenova, SolidarMed SMART Programme, Masvingo, Zimbabwe; Matthew Fox, Themba Lethu Clinic, Johannesburg, South Africa; Hans Prozesky, Tygerberg Academic Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa; Karl Technau, Empilweni Clinic, Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa; Shobna Sawry, Harriet Shezi Children's Clinic, Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, Soweto, South Africa.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. [March 9th 2015];HIV estimates with uncertainty bounds 1990-2013. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/HIV2013Estimates_1990-2013_22July2014.xlsx.

- 2.Biggar RJ, Frisch M, Goedert JJ. Risk of cancer in children with AIDS. AIDS-Cancer Match Registry Study Group. JAMA. 2000;284:205–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kest H, Brogly S, McSherry G, Dashefsky B, Oleske J, Seage GR., 3rd. Malignancy in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in the United States. Pediatric Infect Dis J. 2005;24:237–242. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000154324.59426.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simard EP, Shiels MS, Bhatia K, Engels EA. Long-term cancer risk among people diagnosed with AIDS during childhood. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:148–154. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefan DC, Wessels G, Poole J, et al. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) among children with cancer in South Africa. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:77–79. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton R, Ziegler J, Beral V, et al. A case-control study of human immunodeficiency virus infection and cancer in adults and children residing in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:622–627. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010601)92:5<622::aid-ijc1256>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinfield RL, Molyneux EM, Banda K, et al. Spectrum and presentation of pediatric malignancies in the HIV era: experience from Blantyre, Malawi, 1998-2003. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2007;48:515–520. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutalima N, Molyneux EM, Johnston WT, et al. Impact of infection with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) on the risk of cancer among children in Malawi - preliminary findings. Infect Agent Cancer. 2010;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiappini E, Galli L, Tovo PA, et al. Cancer rates after year 2000 significantly decrease in children with perinatal HIV infection: a study by the Italian Register for HIV Infection in Children. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:97–101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohner E, Valeri F, Maskew M, et al. Incidence rate of Kaposi Sarcoma in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Southern Africa: a prospective multicohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67:547–554. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. Cohort Profile: the international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mbulaiteye SM, Katabira ET, Wabinga H, et al. Spectrum of cancers among HIV-infected persons in Africa: the Uganda AIDS-Cancer Registry Match Study. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:985–990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGowan CC, Cahn P, Gotuzzo E, et al. Cohort Profile: Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV research (CCASAnet) collaboration within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) programme. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:969–976. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS, et al. Cohort profile: the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:294–301. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kariminia A, Chokephaibulkit K, Pang J, et al. Cohort profile: the TREAT Asia pediatric HIV observational database. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:15–24. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies MA, Keiser O, Technau K, et al. Outcomes of the South African National Antiretroviral Treatment Programme for children: the IeDEA Southern Africa collaboration. S Afr Med J. 2009;99:730–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Department of Health South Africa [March 9th 2015];National antiretroviral treatment guidelines. 2004 Available at: http://southafrica.usembassy.gov/media/2004-doh-art-guidelines.pdf.

- 18.National Department of Health South Africa . Guidelines for the management of HIV in children. 2nd edition. National Department of Health; SA: 2010. Available at: In. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson A, Wainwright RD, Stones DK, et al. Malignancies in South African children with HIV. Pediatric Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:111–117. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31829cdd49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chevrette A. [March 9th 2015];G-LINK : A Probabilistic Record Linkage System. Available from: http://www.norc.org/PDFs/May%202011%20Personal%20Validation%20and%20Entity%20Res olution%20Conference/G-Link_Probabilistic%20Record%20Linkage%20paper_PVERConf_May2011.pdf.

- 21.World Health Organization [March 9th 2015];Intermin WHO clinical staging of HIV/AIDS and HIV/AIDS case definition for surveillance - African region. 2005 Available from : http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/clinicalstaging.pdf.

- 22.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray . GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2013. [September 17th 2015]. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caselli D, Klersy C, de Martino M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-related cancer in children: incidence and treatment outcome--report of the Italian Register. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3854–3861. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.22.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heidari S, Mofenson LM, Bekker LG. Realization of an AIDS-free generation: ensuring sustainable treatment for children. JAMA. 2014;312:339–340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsiao NY, Stinson K, Myer L. Linkage of HIV-infected infants from diagnosis to antiretroviral therapy services across the Western Cape, South Africa. PloS one. 2013;8:e55308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprague C, Chersich MF, Black V. Health system weaknesses constrain access to PMTCT and maternal HIV services in South Africa: a qualitative enquiry. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woldesenbet SA, Jackson D, Goga AE, et al. Missed Opportunities for Early Infant HIV Diagnosis: Results of A National Study in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:e26–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department: Health, Republic of South Africa [March 9th 2015];The South African antiretroviral treatment guidelines 2013. Version 14 March 2013. Available at: http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/2013%20ART%20Guidelines-Short%20Combined%20FINAL%20draft%20guidelines%2014%20March%202013.pdf.

- 30.World Health Organization [April 6, 2016];Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. 2015 Sep; Available at: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186275/1/9789241509565_eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed]

- 31.National Department of Health South Africa National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. [April 6 2016];2015 Apr; Available at: https://www.scribd.com/doc/268965647/National-Consolidated-Guidelines-for-PMTCT-and-the-Management-of-HIV-in-Children-Adolescents-and-Adults. [Google Scholar]