Abstract

Study Objectives:

Suicide is a serious public health problem, and suicide rates are particularly high in South Korea. Insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for suicidal ideation; however, little is known about the mechanisms accounting for this relationship in this population. Based on the premise that insomnia can be lonely (e.g., being awake when everyone else is asleep), the purpose of this study was to examine whether greater insomnia severity would be associated with higher levels of thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation, and whether thwarted belongingness would mediate the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation.

Methods:

Predictions were tested in a sample of 552 South Korean young adults who completed self-report measures of insomnia severity, suicidal ideation, and thwarted belongingness.

Results:

Greater insomnia symptom severity was significantly and positively associated with thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation. Mediation analyses revealed that thwarted belongingness significantly accounted for the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation.

Conclusions:

These findings highlight the potential importance of monitoring and therapeutically impacting insomnia and thwarted belongingness to help reduce suicide risk.

Citation:

Chu C, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Ringer FB, Hames JL, Suh S, Joiner TE. Is insomnia lonely? Exploring thwarted belongingness as an explanatory link between insomnia and suicidal ideation in a sample of South Korean university students. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(5):647–652.

Keywords: insomnia, thwarted belongingness, suicidal ideation, interpersonal theory of suicide, South Korea

INTRODUCTION

Suicide has repeatedly emerged as a leading cause of death worldwide.1 Rates of suicide and suicide attempts appear to be especially elevated in South Korea, particularly among young adult females.2 Alarmingly, South Korea, which has been consistently ranked among countries with the highest suicide rates,3 has also experienced a twofold increase in deaths by suicide over the past two decades.4 To inform suicide prevention efforts both among high-risk South Korean young adults and high-risk individuals globally, research is needed not only to identify risk factors for suicide, but also to understand how these risk factors may be mechanistically and theoretically linked to suicide ideation, attempts, and fatalities.

Considered one of the most important warning sign for suicide,5 insomnia is a particularly robust risk factor for suicide.6,7 A number of studies have demonstrated that insomnia is strongly associated with suicidal ideation cross-sectionally8,9,10 and longitudinally,11,12 even when controlling for hopelessness and depression.13 Furthermore, several studies have established a link between insomnia and death by suicide among adolescents,14 adults,15 and older adults,16 underscoring insomnia as a critical risk factor for suicide. In a population-based longitudinal study of non-depressed individuals in South Korea, those with persistent insomnia were nearly two times more likely to have suicidal ideation as compared to those without insomnia (odds ratio = 1.86).17

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Rates of suicide are particularly high in South Korea. There is no research examining the role of insomnia, a significant risk factor for suicide, in the theoretical context of the interpersonal theory of suicide in this population.

Study Impact: This study informs suicide prevention efforts among individuals suffering from insomnia in South Korea and globally. Treatment of thwarted belongingness may be indicated for individuals simultaneously presenting with severe insomnia and suicidal symptoms.

Despite strong evidence of the association between insomnia and suicide, little is known about the underlying mechanisms by which insomnia may be linked to increased suicide risk. Although several hypotheses have been proffered (e.g., emotion dysregulation as an explanatory link16,18; insomnia as a component of overarousal, which is also a risk factor for suicide13), these conjectures have largely been untested. To further delineate the connection between insomnia and suicide, it thus may be useful to turn to theoretical models of suicide—in particular, the interpersonal theory of suicide.

The interpersonal theory of suicide19,20 was developed in part to organize seemingly disparate risk factors for suicide into a single framework. This theory asserts that two constructs are needed for the development of suicidal desire: perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Perceived burdensomeness is conceptualized as the belief that one is a burden to family, friends, and/or society; thwarted belongingness is characterized by feelings of loneliness or a lack of meaningful social relationships. The theory proposes that active suicidal desire arises when an individual is hopeless that either construct will improve. However, an individual will not enact lethal self-harm unless she or he additionally has the capability for suicide (i.e., elevated physical pain tolerance, fearlessness about death). Thus, individuals who die by suicide must not only have the desire for suicide but also the capacity for lethal self-injury.

Considering the increasing body of support for the interpersonal theory,21,22 this theory may provide a useful framework for understanding why insomnia appears to be a robust suicide risk factor. In considering this theory, one potential avenue through which insomnia may have an effect on suicidal desire is by elevating and exacerbating feelings of thwarted belongingness. Insomnia is characterized by significant difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up too early23; therefore, an individual suffering from insomnia is likely to experience long periods of being awake when most others are asleep. The prolonged duration of struggling to fall asleep late at night or in the very early morning may contribute to feelings of loneliness or social isolation.

Preliminary support exists for this hypothesized pathway. For example, we are aware of data from six unique samples (e.g., community high-risk, outpatient, student, and military) found that insomnia was significantly associated with increased feelings of loneliness both cross-sectionally and prospectively. Another investigation examining insomnia and suicide risk in two samples produced mixed results.24 In the first sample, insomnia was no longer associated with increased suicide risk after controlling for interpersonal theory constructs, suggesting that these constructs may play an important role in explaining the robust link between insomnia and suicide. However, in the second sample, insomnia remained significantly associated with suicide risk even after controlling for the theory constructs, indicating that insomnia and the interpersonal theory constructs may represent independent pathways to suicide risk and thus may explain unique variance. Considering equivocal results from multiple studies, further studies examining the relation between insomnia, loneliness, and suicide are needed.

The Current Study

In order to better understand the mechanisms by which insomnia confers risk for suicide, the current study aimed to examine the association between insomnia symptom severity, feelings of thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation in a sample of undergraduates in South Korea. As mentioned previously, rates of suicide are especially elevated among young adults in South Korea, particularly females2–4; thus, there is strong rationale to elucidate pathways to risk in this population. Additionally, thwarted belongingness may in fact be an important factor to consider in clarifying the association between insomnia and suicide in a collectivistic culture such as South Korea, compared to other individualistic cultures, such as the United States. In line with prior research and the interpersonal theory's propositions, we hypothesized that higher levels of insomnia severity would be significantly associated with greater thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation. Further, it is hypothesized that thwarted belongingness will serve as an explanatory factor in the association between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 552 college undergraduates, primarily female (74.5%), recruited from psychology courses across four major universities in Seoul and Daejorn, South Korea. Average age was 21.53 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.25, range 18–34). 28.2% of the sample were first-year, 11.9% were second-year, 21.1% were third-year, and 38.8% were fourth-year students. Approximately half of participants lived with their parents (53.2%), 24.9% lived alone, 11.2% lived with friends, 1.3% lived with another relative, 0.7% lived with spouse/significant other, and 8.3% lived with someone else.

Procedure

Participants completed each of the following measures as part of a larger study. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation and were compensated with course credit following completion of the study. This research was approved by the Sungshin Women's University's Institutional Review Board.

Measures

All questionnaires below were translated from English to Korean, and then back-translated from Korean to English and compared with the original version by an independent translator who was bilingual and a native English speaker.

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

The ISI is a seven-item self-report measure that assesses the severity and impact of insomnia and sleep disturbances over the past week.25 Participants respond to items assessing insomnia, sleep satisfaction, noticeability of impairment, sleep problem-related worry/distress, and interference with daily functioning on a five-point scale (0 to 4). ISI total scores range from 0 to 28, with clinical cutoffs established for subthreshold (total score = 8–14), moderate (total score = 15–21), and severe (total score > 22) clinical insomnia.27 Previous research has provided evidence for the ISI's reliability, validity, and sensitivity in detecting sleep difficulty changes.27 Internal consistency was adequate in the current sample (α = 0.76).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire – Thwarted Belongingness Subscale (INQ)

The thwarted belongingness subscale of the INQ consists of nine items that assess participants' current levels of thwarted belongingness.26 Responses are rated utilizing a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true for me) to 7 (Very true for me). Positive items are reverse coded, such that higher scores reflect higher levels of thwarted belongingness. Clinical cutoffs have yet to be established for the INQ. The thwarted belongingness subscale demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (α = 0.87).

Depressive Symptoms Inventory–Suicidality Subscale (DSI-SS)

The DSI-SS is a four-item self-report measure designed to assess the presence and severity of suicidal thoughts, plans, and urges.27 Each item consists of a group of statements ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe suicidality. Participants are asked to select the statement that best describes their experiences within the past 2 w. A total score of 3 has been recommended as a cutoff for clinically signifi-cant risk; however, in clinical practice settings, nonzero scores may still warrant further investigation.28 Previous research has found the DSI-SS to have strong psychometric properties,29 and internal consistency in the current sample was high (α = 0.93).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 23 (Armory, NY). Missing data, which were minimal (< 3%), were addressed using pairwise deletion. A post hoc power analysis for the current study conducted using G*Power indicated sufficient power (0.85) to detect small effects (f2 = 0.02). To test the hypothesis that insomnia severity is associated with levels of thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation, multiple regression analyses were conducted with total ISI score entered as a predictor of the INQ belongingness subscale score and DSI-SS total score. Standardized regression coefficients are presented in Figure 1. The bootstrap technique was used to test for the mediating effects of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation. In order to test the specificity of thwarted belongingness as the mediator, mediation analyses were also conducted with thwarted belongingness as the independent variable and insomnia severity as the mediator. Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS, following procedures recommended by Hayes.30 The indirect effects of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation were evaluated using a bootstrapping resampling procedure: 5,000 bootstrapped samples were drawn from the data, and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate the indirect effects of each of the resampled datasets. (We are aware of data suggesting that when variance from depressive symptoms is removed from suicidal ideation, what results is mostly error variance. Thus, depressive symptoms was not entered as a covariate.)

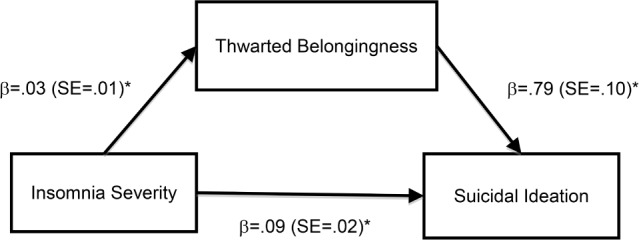

Figure 1. Thwarted belongingness mediating the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation.

Standardized path coefficients (β) are presented with standard errors (SE) in parentheses. The indirect effect of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation was significant (95% confidence interval ranged from 0.0116, 0.0380). *p < 0.001.

RESULTS

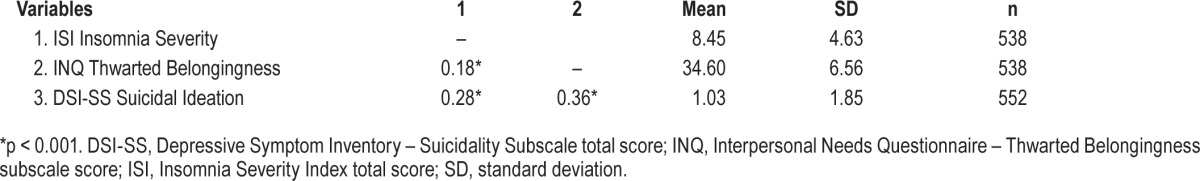

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between all study variables are presented in Table 1. Consistent with study hypotheses, higher insomnia symptom severity was associated with significantly higher levels of thwarted belongingness (β = 0.18, p < 0.001, partial r2 (pr2) = 0.03) and suicidal ideation (β = 0.28, p < 0.001, pr2 = 0.08). Multicollinearity was examined for the regression equations; tolerance and variance inflation factor values were within the acceptable ranges (> 0.10 or < 10, respectively). Suppression was also examined for all regression equations; β values were within the acceptable range (β < zero-order correlation).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables.

Figure 1 presents the path coefficients from the bootstrapped regression and mediation analyses for the effects of insomnia severity on suicidal ideation through thwarted belongingness. For analyses examining the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation, controlling for thwarted belongingness, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.18, F[2,532] = 57.56, p < 0.001). Insomnia severity significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (β = 0.03, standard error [SE] = 0.01, p < 0.001), and thwarted belongingness significantly predicted suicidal ideation (β = 0.79, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001). The direct effects of insomnia severity on suicidal ideation remained significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness (β = 0.09, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation was estimated to be between 0.0117 and 0.0374 (95% confidence interval [CI]), indicating significance (R2 = 0.03, κ2 = 0.06).

Mediation analyses indicated that insomnia severity was not a significant mediator of the relationship between thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation (95% CI: −0.0566, 0.0033). This supports the specificity of the roles of the independent variable (insomnia severity) and the mediator (thwarted belongingness) in our analyses.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine (1) the extent to which insomnia severity is associated with higher levels of thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation, and (2) whether thwarted belongingness as an explanatory link between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation. Consistent with predictions, results indicated that greater severity of insomnia symptoms was significantly and positively associated with feelings of thwarted belongingness and levels of suicidal ideation. Further, thwarted belongingness significantly and specifically accounted for the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation.

Our findings suggest that insomnia not only contributes to loneliness (i.e., sleep disturbances are associated with increased feelings that one does not belong and one is alone), but also that this loneliness may help to explain the robust relationship between insomnia and suicide risk. This finding is consistent with research across a variety of samples, including adolescents, student, community high-risk, outpatient, and military samples, demonstrating an association between insomnia and loneliness.25,26,31

There are several potential explanations for the link between insomnia and loneliness. First, the actual time spent awake when the majority of people are sleeping can contribute to loneliness. Second, previous research has indicated that individuals who experience poor sleep tend to have difficulties forming and maintaining interpersonal relationships,32 poorer coping skills, and increased reactivity to daily stressors.33 These characteristics or symptoms may be associated with an increased likelihood of interpersonal conflicts, which, in turn, lead to greater feelings of thwarted belongingness. Alternatively, it is possible that individuals who experience sleep disturbances also experience daytime sleepiness, which may lead to decreased ability to experience rewarding social connections and increased feelings of loneliness. Although this study did not examine these specific factors, future studies examining the mechanisms underlying this relationship will be informative.

Our findings also add to the growing body of literature supporting the relationship between insomnia severity and suicidal ideation6,7,19 and, additionally, extend prior work by suggesting that sleep disturbances contribute to increased suicidal desire by reducing one's feelings of connectedness with others. This both aligns and contrasts with findings from prior studies. In one of the two undergraduate samples examined by Nadorff and colleagues,25 the authors found that insomnia severity predicted suicidal behavior above and beyond thwarted belongingness and the other variables of the interpersonal theory of suicide. One possible explanation for this discrepancy in findings is the use of different outcome variables. Nadorff and colleagues25 used a measure of suicidal ideation and behavior, whereas the present study utilized a measure specifically assessing ideation.

Alternatively, cultural differences may have accounted for these distinct findings. Given that South Korean culture is highly collectivistic,34 social relationships, particularly those with one's family, are of great importance. Research examining young adults raised in collectivistic cultures has found that a heightened tendency to perceive that they failed to meet their family's standards was associated with an intensification of the effect of thwarted belongingness on suicidal ideation.35 Thus, in a culture that emphasizes community and self-suppression, young adults feeling disconnected from others may be more vulnerable to suicidal desire. Furthermore, individuals from collectivistic cultures tend to be reluctant to discuss symptoms of mental illness and seek treatment,36 which may exacerbate symptoms. Future research should seek to replicate this relationship across various cultures to determine the role of culture in influencing suicide risk associated with insomnia.

That insomnia is associated with greater feelings of thwarted belongingness and higher levels of suicidal ideation among individuals with insomnia is important from a clinical standpoint. For one, these findings highlight the importance of monitoring and addressing insomnia symptoms throughout treatment, as this proactive approach may help reduce suicide risk. Questions probing the individual's nighttime sleep routines and average quality and quantity of sleep are particularly informative regarding insomnia severity. Patients experiencing significant sleep disturbances may benefit from targeted treatment for insomnia, such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I),37 a treatment that has also shown efficacy in decreasing symptoms of suicidal ideation.38 Given that patients may be experiencing thwarted interpersonal belongingness, CBT-I delivers in a group format, which has been shown to be on par in effectiveness with individually-delivered CBT-I,39 may be particularly useful as it facilitates social interactions and peer support. As such, group CBT-I may also increase feelings of connections with others and decrease isolation. Furthermore, should patients report symptoms of insomnia, regular suicide risk assessments would be an appropriate adjunct to the treatment approach. Given the role of thwarted belongingness in the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation, our findings also support the utility of assessing and addressing symptoms of thwarted belongingness in treatment. For example, cognitive therapy approaches, including the identification and restructuring of distorted cognitions regarding whether one belongs, may be useful.40

The current study should be interpreted with its limitations in mind. Given that this study was conducted using undergraduates in South Korea, these findings may not be generalizable to older or clinical populations in other countries and across cultures. Although levels of thwarted belongingness were particularly high, insomnia severity and suicidal ideation were subthreshold and relatively low in this sample. As rates of suicide and social disconnection are higher among the elderly,41 loneliness may differentially affect the relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation in older populations. Thus, future studies should seek to replicate these findings across samples of varying ages, culture, and severity of insomnia and ideation. Furthermore, though rates of suicide are estimated to be increasing in South Korea, there exists a cultural belief that suicide is an individual problem42 that affects willingness to seek help and to discuss mental health symptoms38; this may have influenced the accuracy of self-reported symptoms of suicidal ideation and behavior in this study. Although participants in this study were reminded of the confidential nature of this study, future studies of suicidal ideation and suicide risk factors in this culture may benefit from use of measures with less face validity, such as implicit measures of suicidal behavior43 and increased emphasis on confidentiality. Relatedly, in this study, insomnia severity was measured using a self-report survey. Despite previous research indicating that the ISI is useful in capturing changes in insomnia symptom severity throughout treatment and demonstrates concurrent validity with sleep diaries,27 measurement of sleep disturbances may be improved in future studies with the inclusion of objective measures (e.g., polysomnography) or sleep diaries. Additionally, the current study was cross-sectional; thus, we were unable to assess whether there was a causal relationship between insomnia and suicidal ideation (although analyses supported the specificity of thwarted belongingness as the mediator). As such, future prospective studies are indicated and may shed light on the trajectory from disturbed sleep to suicide risk. Delineating the nature of the relationship between insomnia, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation may reveal additional intervention avenues for patients experiencing suicidal ideation.

In summary, the current study provided evidence that more severe insomnia symptoms were associated with greater levels of suicidal ideation, and thwarted belongingness significantly mediated this relationship in a large sample of young adults from four universities in South Korea. These results represent an important contribution to the literature, as they underscore the importance of examining insomnia as a risk factor for suicidal ideation across cultures. They also have various clinical implications for managing suicide risk in individuals with insomnia. Given that rates of suicide-related symptoms in South Korea have increased overall in the recent years,4 there is a need to better understand suicide risk in this population. Our hope is that these findings will contribute to effective suicide prevention and treatment efforts, and we look forward to the replication and application of these findings in future studies.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry-supported study. This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (5 T32 MH093311-04) and a grant by the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs under Award No. (W81XWH-10-2-0181). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the MSRC or the Department of Defense. This research was conducted at Sungshin Women's University. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions: Carol Chu analyzed the data, drafted the Results and the Discussion, and revised the manuscript. Melanie Hom drafted the Introduction, and provided detailed critical feedback. Megan Rogers drafted the Methods and provided detailed critical feedback. Fallon Ringer drafted the Limitations/Future Directions section and provided detailed critical feedback. Dr. Hames drafted the Abstract and provided detailed critical feedback. Dr. Suh provided the data and detailed critical feedback. Dr. Joiner provided detailed critical feedback.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CBT-I

cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- CI

confidence interval

- DSI-SS

Depressive Symptom Inventory – Suicidality Subscale

- INQ

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- PR

partial correlation

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- SD

standard deviation

- SE

standard error

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Suicide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeon HJ, Lee JY, Lee YM, et al. Lifetime prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation, plan, and single and multiple attempts in a Korean nationwide study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:643–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef3ecf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD Factbook 2013. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2013.

- 4.Kwon JW, Chun H, Cho SI. A closer look at the increase in suicide rates in South Korea from 1986-2005. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Suicide warning signs. [Accessed August 27, 2015]. Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SVP05-0126/SVP05-0126.pdf.

- 6.Bernert RA, Kim JS, Iwata NG, Perlis ML. Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:e1160–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapierre S, Boyer R, Desjardins S, et al. Daily hassles, physical illness, and sleep problems in older adults with wishes to die. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2012;24:243–52. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjostrom N, Waern M, Hetta J. Nightmares and sleep disturbances in relation to suicidality in suicide attempters. Sleep. 2007;30:91–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Functioning of adolescents with symptoms of disturbed sleep. J Youth Adolesc. 2001:301–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA. Sleep problems, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviors in adolescence. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong MM, Brower KJ. The prospective relationship between sleep problems and suicidal behavior in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM, et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:743–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodaka M, Matsumoto T, Katsumata Y, et al. Suicide risk among individuals with sleep disturbances in Japan: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Sleep Med. 2014;15:430–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.11.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernert RA, Turvey CL, Conwell Y, Joiner TE. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with risk for death by suicide during a 10-year period: a longitudinal, population-based study of late life. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1129–37. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh S, Kim H, Yang H, Cho E, Lee S, Shin C. Longitudinal course of depression scores with and without insomnia in non-depressed individuals: a 6-year follow-up longitudinal study in a Korean cohort. Sleep. 2013;36:369–76. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3:735–43. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Soubelet A, Mackinnon AJ. A test of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in a large community-based cohort. J Affect Disord. 2013;144:225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:634–46. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadorff MR, Anestis MD, Nazem S, Harris HC, Winer ES. Sleep disorders and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide: Independent pathways to suicidality? J Affect Disord. 2014;152–4:505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 2012;24:197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metalsky GI, Joiner TJ. The Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire. Cognit Ther Res. 1997;21:359–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joiner TE, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: reliability and validity data from the Australian National General Practice Youth Suicide Prevention Project. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:471–81. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro JD, Braithwaite SR, Pfaff JJ, Joiner TE. Examining a brief suicide screening tool in older adults engaging in risky alcohol use. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2012;42:405–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes AF. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahon N. Loneliness and sleep during adolescence. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78:227–31. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carskadon M. Patterns of sleep and sleepiness in adolescents. Pediatrician. 1990;17:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morin C, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:259–67. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofstede G. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1984. Culture's consequences: international differences in work-related values. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang K, Wong Y, Fu C. Moderation effects of perfectionism and discrimination on interpersonal factors and suicide ideation. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60:367–78. doi: 10.1037/a0032551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, Mak W. Seeking professional help: etiology beliefs about mental illness across cultures. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55:442–50. doi: 10.1037/a0012898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edinger J, Means M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:539–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trockel M, Karlin BE, Taylor CB, Brown GK, Manber R. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on suicidal ideation in veterans. Sleep. 2015;38:259–65. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastien CH, Morin CM, Ouellet MC, Blais FC, Bouchard S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: comparison of individual therapy, group therapy, and telephone consultations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:653–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joiner TE, Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Rudd MD. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. The interpersonal theory of suicide: guidance for working with suicidal clients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Orden K, Conwell Y. Suicides in late life. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:234–41. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Yoon J. Suicide, an urgent health issue in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:345–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nock MK, Park JM, Finn CT, Deliberto TL, Dour HJ, Banaji MR. Measuring the suicidal mind: implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:511–7. doi: 10.1177/0956797610364762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]