Abstract

Little is known of the relationships between dietary patterns and cardiovascular risk factors in China. We therefore designed a 3-year longitudinal study to evaluate the impacts of dietary patterns on changes in these factors among Chinese women. A total of 1,028 subjects who received health examination in 2011 and 2014 were recruited. Three major dietary patterns (“vegetable pattern”, “meat pattern”, and “animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol pattern”) were derived by principal component analysis based on validated food frequency questionnaires. Cardiovascular risk factors were standardized to create within-cohort z-scores and the changes in them were calculated as the differences between 2011 and 2014. Relationships between dietary patterns and changes in cardiovascular risk factors were assessed using general linear model. After adjustment for potential confounders, changes in total cholesterol and fasting blood glucose decreased across the tertiles of vegetable pattern (p for trend = 0.01 and 0.04, respectively). While, changes in diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol increased across the tertiles of animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol pattern (p for trend = 0.02, 0.01, and 0.02, respectively). The findings suggest that vegetable pattern was beneficially related to cardiovascular risk factors, whereas animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol pattern was detrimental related to these factors among apparently healthy Chinese women.

Keywords: dietary pattern, principal component analysis, cardiovascular risk factors, Chinese women, longitudinal study

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide.(1) Incidentally, it is now the most prevalent and debilitating disease affecting the health of Chinese populations.(2–4) According to the report on CVD in China in 2010, the number of patients with CVD was 230 million, one in 5 adults was believed to suffer from CVD. Moreover, it is also the leading cause of death in China, accounting for 41% of deaths from any cause annually.(5) As we all know, environmental factors may contribute to the risk of CVD to a large extent, and dietary factor, as an aspect of environmental factors, plays a vital role in it. However, since the 1950s, especially in the last 20 years, transitions in eating behaviors tend to emerge in parallel with industrialization and economic development. Average consumption of processed meats, snacking, and fried foods have increased, while the consumption of cereals and tubers have decreased.(6–8) This change along with the shift of disease pattern from predominantly communicable diseases to noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity.(9)

The major cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs), such as high body mass index (BMI), high blood pressure (BP), dyslipidemia and high fasting blood glucose (FBG) have been well established.(10) Previous studies exploring the effects of dietary factors on CVRFs have focused predominantly on individual nutrients or a single food, which oversimplify the complexity of combinations and interactions of nutrients and foods.(11,12) In contrast, dietary patterns represent a broader view of foods and nutrients consumption, and be more predictive of disease risk than individual foods or nutrients.(13) Nevertheless, only a few studies in Western countries have examined the effects of dietary patterns on the CVRFs. Generally, these studies have identified that greater adherence to the prudent or healthy dietary pattern might be related to a decreased in CVRFs, whereas greater adherence to the Western dietary pattern might be related to an increased in CVRFs.(14–16) To our knowledge, no studies on the associations between dietary patterns and the longitudinal changes in CVRFs have been conducted among Chinese populations.

Thus, we designed a 3-year longitudinal study to identify dietary patterns via principal component analysis and to investigate their impacts on the longitudinal changes in CVRFs among apparently healthy Chinese women. Findings from this study may be potentially of great use for future prevention strategies of CVD among Chinese populations.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We conducted a 3-year longitudinal study to investigate the associations between dietary patterns and CVRFs in a representative sample of healthy Chinese women. All subjects recruited in 2011 were re-invited in 2014 to the longitudinal study based on health examinations from the Health Education and Guidance Center of Heping District in Tianjin, China. Of 2,459 eligible individuals, 2,191 (89.1%) responded.

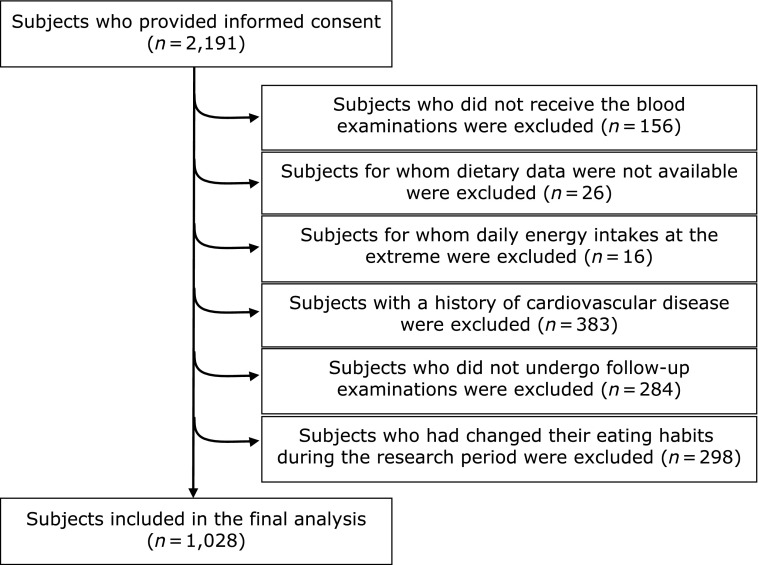

The enrollment process is described in Fig. 1. Because the dietary patterns varied in different gender and the number of male subjects (n = 332) was too small to perform principal component analysis, males were excluded from current analysis.(17) We also excluded subjects who did not receive the blood biochemical test (n = 156), who did not have any dietary information (n = 26), whose daily energy intakes at the extreme 0.5% upper or lower ends of the range (cut-off points were 806 kcal and 4,910 kcal, n = 20), who reported a history of cardiovascular disease (n = 379) and who changed their diet and lifestyle during the longitudinal study (n = 298). Of these invited, 284 subjects were lost to follow-up. Consequently, the final sample was composed of 1,028 healthy women.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the sample selection process

Ethical approval and permission to conduct this study were obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Dietary intake and covariates assessments

A validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that included 81 food items with specified serving sizes was used to assess dietary intake of the subject.(18) The FFQ had 7 frequency options as follows: (i) almost never; (ii) less than 1 time per week; (iii) once a week; (iv) 2–3 times per week; (v) 4–6 times per week; (vi) once a day; (vii) more than 2 times per day. The subjects recalled the frequency of each food consumption over the past month. The mean daily consumption of food items, nutrients and total energy were calculated by converting the selected frequency category for each food to a daily intake, using China Food Composition Tables as the database.(19) Finally, 81 items were categorized into 25 food groups according to the similarities of the nutritional composition and culinary usage, which were used to derived dietary patterns via principal component analysis (Supplemental Table 1*).

Sociodemographic variables including age, gender, educational level, history of disease, family history of cardiovascular disease, smoking and drinking status were also collected by a structured questionnaire. The education level was divided into 2 categories: less than college degree and college degree or above. Family history of cardiovascular illness was noted from ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to relevant question. An inquiry on smoking status included never, former or current smoker. For drinking status, subjects were asked the frequency of drinking, such as never, former, sometimes and everyday.

All the data were collected in 2014 and the subjects were asked whether or not changed their eating habits and lifestyle during the past 3 years.

Anthropometric and biochemical assessments

Each subject’s height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm and 0.1 kg wearing light clothes and no shoes. BMI was then defined as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured twice after 5 min of rest in the seated position and the mean of them was used in the analysis. Blood samples were drawn from the antecubital vein after fasting for at least 12 h. Serum total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and FBG were measured using the enzymatic methods with an automatic biochemical analyzer (TBA-40, Tokyo, Japan). During 3-year follow-up, all these variables were measured twice at 2011 and 2014.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, ver. 19). Dietary patterns were derived by using principal component analysis which reduced the 25 food groups into a smaller number of underlying factors. All foods were first converted into grams per day from the FFQ, then principal component analysis method was applied, factors were extracted with varimax rotation to maintain an uncorrelated state and improve interpretability. Finally, three major factors (dietary patterns) were retained on the basis of an evaluation of the eigenvalues (>1.0), a scree plot, and factor interpretability. We named them: (i) Vegetable pattern, (ii) Meat pattern, and (iii) Animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol (ADA) pattern, according to the foods that loaded highly on each pattern. Factor scores for each pattern were calculated as the sum of the factor loading coefficients and the standardized daily intake of each food associated with that pattern. A higher score corresponded with greater conformity to the derived pattern. Subjects were divided into tertiles by scores for further analyses.

The baseline data and the 3-year changes in CVRFs (i.e., SBP, DBP, BMI, TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, and FBG) were calculated for subjects who had not received medical treatments in the surveys. Due to skewed distribution, and in order to compare on same scale between 2011 and 2014, all CVRFs were standardized using a Fisher-Yates transformation to a normally distributed variable with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, producing within-cohort z-scores. The longitudinal changes in CVRFs were calculated as the differences in z-scores between two time points. Therefore, increases were represented by positive values and decreases by negative values.

All data are presented as the mean (95% confidence interval) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. We first performed cross-sectional analyses to study baseline characteristics, nutrition and dietary intakes across increasing tertiles of dietary pattern factor scores using general linear model and χ2 test for continuous and categorical data. We then performed a longitudinal analysis to examine the relationships between dietary patterns and the 3-year changes in CVRFs using general linear model. For analysis, the changes of CVRFs were used as dependent variables and the dietary pattern factor score tertiles were considered as independent variables. We created two models with different levels of adjustment. Model 1 adjusted for age, while model 2 additionally adjusted for total energy intake, the longitudinal change of BMI, education level, smoking status, drinking status and family history of cardiovascular disease. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the present study, three main dietary patterns were derived from the principal component analysis. The factor loadings for each dietary pattern are listed in Table 1. The first pattern identified as vegetable pattern which explained 15.45% of the total variance of food intake. Foods that loaded highly on this pattern were predominantly melon vegetables, starchy tubers, root vegetables, leafy and flowering vegetables, fungi and algae, lotus root, allium vegetables, fruits, fish, coarse cereals, tea, soybean, nuts, wheat, and dairy products. The second pattern identified as meat pattern which explained 7.66% of the total variance. It was typified by a greater consumption of red meat, rice, poultry, and eggs. The third pattern identified as ADA pattern which explained 7.57% of the total variance. It was characterized by a variety of animal offal, fish, shellfish and mollusc, condiments, convenience foods and desserts, alcohol and beverages, poultry, and red meat. In addition, answer scores of the 81 food items among tertiles of each dietary pattern are presented in Supplemental Table 2*.

Table 1.

Factor loadings for 3 dietary patterns derived from a principal component analysis†

| Food group | Vegetable pattern | Meat pattern | ADA pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 0.28 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Rice | 0.09 | 0.64 | –0.14 |

| Coarse cereals | 0.32 | 0.00 | –0.01 |

| Congee | 0.15 | 0.26 | –0.03 |

| Starchy tubers | 0.68 | –0.06 | 0.06 |

| Soybean | 0.29 | 0.06 | –0.01 |

| Other legumes | 0.24 | –0.06 | –0.05 |

| Root vegetables | 0.66 | –0.04 | 0.06 |

| Melon vegetables | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Allium vegetables | 0.56 | 0.13 | 0.29 |

| Leafy and flowering vegetables | 0.65 | 0.22 | –0.04 |

| Lotus root | 0.59 | –0.01 | 0.26 |

| Fungi and algae | 0.59 | –0.04 | 0.28 |

| Fruits | 0.57 | –0.02 | 0.08 |

| Nuts | 0.26 | –0.02 | –0.08 |

| Red meat | –0.06 | 0.77 | 0.21 |

| Poultry | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.27 |

| Animal offal | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.80 |

| Dairy products | 0.24 | 0.09 | –0.02 |

| Eggs | 0.15 | 0.56 | –0.11 |

| Fish, shellfish and mollusc | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.59 |

| Convenience foods and desserts | –0.14 | –0.01 | 0.35 |

| Condiments | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Tea | 0.29 | 0.18 | –0.19 |

| Alcohol and beverages | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.29 |

| Variance explained (%) | 15.45 | 7.66 | 7.57 |

†Absolute values >0.20 are shown in bold. ADA, animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol.

Table 2 shows the age-adjusted baseline characteristics of subjects according to tertiles of dietary pattern scores. Subjects in the highest tertile of the vegetable pattern tended to be older, and had a lower proportion of occasional drinkers when compared to whom in the lowest tertile in this pattern. In contrast, subjects in the highest tertile of meat pattern or ADA pattern were more likely to be younger than whom in the lowest tertiles in these patterns. No other significant differences were observed among tertiles of dietary pattern factor scores.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects according to tertiles of each dietary pattern scores†

| Characteristics | Vegetable pattern |

Meat pattern |

ADA pattern |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | |||

| No. of subjects | 343 | 343 | 342 | — | 343 | 343 | 342 | — | 343 | 343 | 342 | — | ||

| Age (years) | 41.5 (40.5, 42.5) | 42.9 (41.8, 44.0) | 46.2 (45.0, 47.5) | <0.01 | 45.7 (44.5, 46.9) | 43.3 (42.2, 44.5) | 41.6 (40.6, 42.6) | <0.01 | 48.0 (46.9, 49.0) | 43.0 (41.8, 44.1) | 39.7 (38.7, 40.7) | <0.01 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 (22.0, 22.6) | 22.3 (22.0, 22.6) | 22.5 (22.2, 22.8) | 0.30 | 22.4 (22.1, 22.7) | 22.5 (22.2, 22.9) | 22.2 (21.9, 22.6) | 0.54 | 22.4 (22.1, 22.8) | 22.3 (22.0, 22.6) | 22.4 (22.1, 22.7) | 0.93 | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 113.0 (111.5, 114.6) | 113.6 (112.0, 115.1) | 114.0 (112.5, 115.6) | 0.37 | 114.1 (112.6, 115.7) | 114.1 (112.5, 115.6) | 112.4 (110.9, 114.0) | 0.13 | 113.5 (111.9, 115.1) | 113.3 (111.7, 114.8) | 113.9 (112.3, 115.4) | 0.74 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | 74.8 (73.8, 75.8) | 74.4 (73.4, 75.4) | 75.0 (74.0, 76.0) | 0.81 | 74.2 (73.2, 75.2) | 75.1 (74.1, 76.1) | 74.9 (73.9, 75.9) | 0.32 | 75.1 (74.1, 76.1) | 74.3 (73.3, 75.2) | 74.8 (73.8, 75.8) | 0.75 | ||

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.9 (4.8, 5.0) | 4.7 (4.6, 4.8) | 4.9 (4.8, 5.0) | 0.87 | 4.8 (4.7, 4.9) | 4.8 (4.8, 4.9) | 4.8 (4.7, 4.9) | 0.90 | 4.9 (4.8, 4.9) | 4.8 (4.7, 4.9) | 4.8 (4.7, 4.9) | 0.42 | ||

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2) | 0.30 | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2) | 0.21 | 1.1 (1.1, 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) | 0.19 | ||

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.6 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.6) | 0.20 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.6 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.6) | 0.20 | 1.6 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.6) | 0.39 | ||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.7) | 2.6 (2.5, 2.6) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.8) | 0.67 | 2.6 (2.6, 2.7) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.7) | 2.6 (2.6, 2.7) | 0.65 | 2.6 (2.6, 2.7) | 2.6 (2.6, 2.7) | 2.6 (2.6, 2.7) | 0.92 | ||

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.3 (5.2, 5.3) | 5.3 (5.3, 5.4) | 5.4 (5.4, 5.5) | 0.12 | 5.4 (5.3, 5.4) | 5.3 (5.3, 5.4) | 5.3 (5.3, 5.4) | 0.09 | 5.4 (5.3, 5.4) | 5.3 (5.3, 5.4) | 5.4 (5.3, 5.4) | 0.41 | ||

| Education (≥college, %) | 76.6 | 76.1 | 75.8 | 0.96 | 72.2 | 79.6 | 76.5 | 0.08 | 78.9 | 75.1 | 74.9 | 0.37 | ||

| Smoking status (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Current-smoker | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.19 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.19 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.39 | ||

| Ex-smoker | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.14 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.14 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.46 | ||

| Drinking status (%) | ||||||||||||||

| Everyday | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.99 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.10 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.06 | ||

| Sometimes | 48.5 | 41.9 | 37.7 | 0.01 | 40.9 | 43.1 | 44.0 | 0.42 | 38.2 | 45.5 | 44.4 | 0.10 | ||

| Ex-drinker | 3.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 0.14 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 0.36 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.26 | ||

| Family history of CVD (%) | 39.5 | 41.9 | 37.4 | 0.58 | 36.5 | 40.8 | 41.4 | 0.20 | 35.9 | 43.1 | 39.8 | 0.29 | ||

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval) or %. ADA, animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; CVD, cardiovascular disease. †Characteristics presented in this table were adjusted for age.

Table 3 and 4 show total energy-adjusted daily nutrients and dietary intakes according to dietary pattern score tertiles. Compared to subjects in the lowest vegetable dietary pattern tertile, those in the highest tertile had a significant higher consumption of total energy, carbohydrate, fiber, wheat, starchy tubers, soybean products, total vegetables, total fruits, nuts, total fish, tea, and a lower consumption of total fat, saturated fatty acid (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), cholesterol, total meats, animal offal, convenience foods and desserts. While compared to subjects in the lowest meat dietary pattern tertile, those in the highest tertile had a significant higher consumption of total energy, total protein, total fat, SFA, cholesterol, rice, total meats, eggs, and a lower consumption of MUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), carbohydrate, fiber, wheat, coarse cereals, soybean products, total fruits, nuts convenience foods and desserts. In addition, compared to subjects in the lowest ADA dietary pattern tertile, those in the highest tertile had a significant higher consumption of total energy, total protein, total fat, SFA, cholesterol, total meats, animal offal, total fish, convenience foods and desserts, condiments, alcohol and beverages, and a lower consumption of MUFA, PUFA, carbohydrate, fiber, rice, cereals and tubers, soybean products, root vegetables, melon vegetables, leafy and flowering vegetables, total fruits, nuts, dairy products, eggs, and tea.

Table 3.

Daily nutrients of the subjects according to tertiles of each dietary pattern scores†

| Nutrients intakes | Vegetable pattern |

Meat pattern |

ADA pattern |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | |||

| Total energy (kcal) | 1,707 (1,644, 1,770) | 1,997 (1,939, 2,056) | 2,555 (2,472, 2,638) | <0.01 | 1,901 (1,827, 1,975) | 1,970 (1,901, 2,039) | 2,387 (2,306, 2,469) | <0.01 | 2,063 (1,987, 2,139) | 1,925 (1,854, 1,996) | 2,272 (2,188, 2,355) | <0.01 | ||

| Protein (g) | 86.9 (85.8, 88.1) | 87.5 (86.4, 88.6) | 86.1 (85.0, 87.3) | 0.39 | 82.9 (81.9, 84.0) | 86.1 (85.1, 87.1) | 91.5 (90.5, 92.6) | <0.001 | 83.7 (82.7, 84.8) | 87.3 (86.2, 88.4) | 89.6 (88.5, 90.6) | <0.01 | ||

| Total fat (g) | 52.1 (51.0, 53.2) | 48.2 (47.2, 49.3) | 43.3 (42.2, 44.5) | <0.01 | 44.7 (43.6, 45.8) | 46.8 (45.7, 47.9) | 52.1 (51.0, 53.2) | <0.01 | 44.8 (43.7, 45.8) | 48.3 (47.2, 49.4) | 50.6 (49.5, 51.7) | <0.01 | ||

| SFA (g) | 13.1 (12.7, 13.5) | 12.1 (11.8, 12.5) | 10.7 (10.3, 11.1) | <0.01 | 10.2 (9.9, 10.5) | 11.6 (11.3, 11.9) | 14.1 (13.8, 14.4) | <0.01 | 11.2 (10.9, 11.6) | 12.0 (11.7, 12.4) | 12.7 (12.3, 13.0) | <0.01 | ||

| MUFA (g) | 15.4 (15.0, 15.8) | 14.0 (13.6, 14.4) | 12.3 (11.9, 12.8) | <0.01 | 16.0 (15.6, 16.4) | 13.4 (13.0, 13.8) | 12.4 (12.0, 12.7) | <0.01 | 14.9 (14.5, 15.3) | 14.0 (13.6, 14.4) | 12.9 (12.5, 13.3) | <0.01 | ||

| PUFA (g) | 11.4 (10.9, 11.9) | 11.2 (10.8, 11.7) | 11.1 (10.7, 11.6) | 0.47 | 12.0 (11.5, 12.4) | 11.2 (10.8, 11.7) | 10.6 (10.1, 11.1) | 0.01 | 11.7 (11.3, 12.2) | 11.5 (11.1, 12.0) | 10.6 (10.1, 11.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Cholesterol (mg) | 578.2 (558.1, 598.2) | 556.1 (537.2, 575.1) | 493.1 (472.5, 513.7) | <0.01 | 455.9 (438.0, 473.7) | 529.7 (512.0, 547.4) | 641.6 (623.5, 659.7) | <0.01 | 505.1 (486.2, 523.9) | 530.9 (511.9, 549.9) | 591.7 (572.6, 610.8) | <0.01 | ||

| Carbohydrate (g) | 315.9 (312.2, 319.6) | 324.7 (321.2, 328.2) | 340.2 (336.4, 344.0) | <0.01 | 338.3 (334.8, 341.8) | 329.8 (326.3, 333.3) | 312.7 (309.1, 316.3) | <0.01 | 337.1 (333.6, 340.7) | 324.4 (320.8, 328.0) | 319.2 (315.6, 322.8) | <0.01 | ||

| Fiber (g) | 19.0 (18.5, 19.5) | 22.1 (21.7, 22.5) | 27.7 (27.2, 28.1) | <0.01 | 24.7 (24.1, 25.2) | 23.2 (22.7, 23.8) | 20.9 (20.3, 21.4) | <0.01 | 24.8 (24.2, 25.3) | 22.5 (22.0, 23.0) | 21.5 (20.9, 22.0) | <0.01 | ||

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval). ADA, animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol; SFA, saturated fatty acid; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid. †Characteristics presented in this table were adjusted for total energy intake.

Table 4.

Daily food intakes of the subjects according to tertiles of each dietary pattern scores†

| Food intakes | Vegetable pattern | Meat pattern | ADA pattern | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | |||

| Wheat (g) | 148.1 (138.7, 157.5) | 139.9 (131.0, 148.8) | 118.5 (108.9, 128.1) | <0.01 | 149.0 (140.0, 158.0) | 136.6 (127.7, 145.5) | 121.0 (111.8, 130.1) | <0.01 | 123.9 (115.0, 132.8) | 147.0 (138.0, 156.0) | 135.7 (126.7, 144.7) | 0.07 | ||

| Rice (g) | 137.0 (127.2, 146.9) | 154.6 (145.3, 164.0) | 136.0 (125.9, 146.2) | 0.90 | 79.8 (72.2, 87.4) | 133.2 (125.7, 140.7) | 214.6 (206.9, 222.3) | <0.01 | 166.3 (157.1, 175.5) | 135.5 (126.2, 144.8) | 125.9 (116.6, 135.2) | <0.01 | ||

| Coarse cereals (g) | 38.8 (34.6, 42.9) | 38.7 (34.7, 42.6) | 40.8 (36.5, 45.0) | 0.54 | 46.8 (42.9, 50.7) | 42.1 (38.2, 46.0) | 29.3 (25.3, 33.3) | <0.01 | 49.1 (45.2, 52.9) | 40.4 (36.5, 44.3) | 28.7 (24.8, 32.6) | <0.01 | ||

| Congee (g) | 70.8 (65.3, 76.2) | 68.4 (63.3, 73.6) | 54.7 (49.1, 60.3) | <0.01 | 56.8 (51.5, 62.0) | 64.8 (59.6, 69.9) | 72.3 (67.0, 77.6) | <0.01 | 72.5 (67.3, 77.7) | 63.4 (58.2, 68.6) | 57.9 (52.7, 63.2) | <0.01 | ||

| Starchy tubers (g) | 29.3 (25.2, 33.4) | 42.0 (38.1, 45.9) | 73.7 (69.5, 77.9) | <0.01 | 60.3 (56.1, 64.5) | 45.2 (41.0, 49.3) | 39.5 (35.3, 43.8) | <0.01 | 54.6 (50.4, 58.8) | 45.7 (41.5, 50.0) | 44.6 (40.4, 48.9) | <0.01 | ||

| Soybean (g) | 58.2 (52.6, 63.7) | 67.6 (62.4, 72.8) | 69.6 (63.9, 75.3) | 0.01 | 69.1 (63.8, 74.4) | 65.2 (59.9, 70.4) | 61.1 (55.7, 66.5) | 0.04 | 69.0 (63.8, 74.2) | 70.1 (64.9, 75.4) | 56.2 (50.9, 61.4) | <0.01 | ||

| Other legumes (g) | 12.7 (10.7, 14.7) | 16.4 (14.5, 18.4) | 19.1 (17.1, 21.2) | <0.01 | 18.0 (16.1, 20.0) | 17.7 (15.7, 19.6) | 12.6 (10.7, 14.6) | <0.01 | 18.2 (16.3, 20.1) | 16.5 (14.6, 18.4) | 13.6 (11.6, 15.5) | <0.01 | ||

| Root vegetables (g) | 23.7 (20.2, 27.2) | 33.0 (29.7, 36.3) | 56.5 (52.9, 60.1) | <0.01 | 45.8 (42.2, 49.3) | 37.8 (34.3, 41.3) | 29.7 (26.1, 33.3) | <0.01 | 44.4 (40.9, 47.9) | 36.0 (32.4, 39.5) | 32.8 (29.3, 36.4) | <0.01 | ||

| Melon vegetables (g) | 128.9 (119.7, 138.1) | 170.0 (161.3, 178.7) | 239.2 (229.8, 248.6) | <0.01 | 178.3 (168.6, 188.1) | 185.8 (176.1, 195.5) | 173.8 (163.9, 183.8) | 0.53 | 196.6 (187.0, 206.1) | 176.6 (166.9, 186.2) | 164.9 (155.2, 174.5) | <0.01 | ||

| Allium vegetables (g) | 15.3 (13.9, 16.7) | 19.1 (17.8, 20.4) | 25.9 (24.5, 27.3) | <0.01 | 19.7 (18.3, 21.0) | 20.8 (19.4, 22.2) | 19.8 (18.4, 21.3) | 0.86 | 19.0 (17.7, 20.4) | 19.3 (17.9, 20.7) | 21.9 (20.5, 23.3) | <0.01 | ||

| Leafy/flowering vegetables (g) | 115.3 (104.7, 125.8) | 167.0 (157.0, 177.0) | 243.3 (232.5, 254.1) | <0.01 | 164.2 (153.0, 175.4) | 175.1 (164.0, 186.2) | 186.2 (174.8, 197.6) | 0.01 | 203.6 (192.8, 214.5) | 169.2 (158.2, 180.2) | 152.6 (141.6, 163.6) | <0.01 | ||

| Lotus root (g) | 8.3 (6.7, 9.9) | 11.3 (9.8, 12.9) | 20.1 (18.4, 21.7) | <0.01 | 15.8 (14.2, 17.4) | 12.9 (11.3, 14.5) | 11.0 (9.4, 12.6) | <0.01 | 12.5 (10.9, 14.1) | 11.8 (10.2, 13.4) | 15.5 (13.9, 17.0) | 0.01 | ||

| Fungi and algae (g) | 16.0 (14.2, 17.9) | 23.1 (21.3, 24.8) | 32.1 (30.2, 34.0) | <0.01 | 27.8 (25.9, 29.6) | 23.3 (21.5, 25.2) | 20.1 (18.2, 22.0) | <0.01 | 21.2 (19.3, 23.0) | 23.3 (21.4, 25.1) | 26.8 (24.9, 28.7) | <0.01 | ||

| Fruits (g) | 292.4 (271.4, 313.4) | 339.7 (319.8, 359.7) | 458.4 (436.9, 480.0) | <0.01 | 412.5 (391.8, 433.2) | 371.1 (350.6, 391.7) | 307.0 (285.9, 328.0) | <0.01 | 415.1 (394.6, 435.7) | 331.8 (311.0, 352.5) | 343.5 (322.7, 364.3) | <0.01 | ||

| Nuts (g) | 23.1 (20.2, 25.9) | 23.6 (20.8, 26.3) | 28.3 (25.3, 31.2) | 0.02 | 31.5 (28.8, 34.3) | 24.7 (22.0, 27.4) | 18.7 (15.9, 21.4) | <0.01 | 32.1 (29.4, 34.8) | 24.2 (21.5, 26.9) | 18.6 (15.8, 21.3) | <0.01 | ||

| Red meat (g) | 56.9 (52.7, 61.0) | 46.0 (42.1, 49.9) | 35.3 (31.1, 39.5) | <0.01 | 22.1 (18.8, 25.4) | 39.5 (36.2, 42.7) | 76.5 (73.1, 79.8) | <0.01 | 35.7 (31.7, 39.6) | 49.3 (45.3, 53.2) | 53.3 (49.3, 57.2) | <0.01 | ||

| Poultry (g) | 37.8 (34.7, 40.8) | 31.9 (29.0, 34.8) | 22.2 (19.1, 25.3) | <0.01 | 18.7 (16.0, 21.5) | 27.2 (24.5, 29.9) | 45.9 (43.1, 48.7) | <0.01 | 22.7 (19.9, 25.6) | 30.7 (27.8, 33.6) | 38.5 (35.6, 41.4) | <0.01 | ||

| Animal offal (g) | 19.0 (16.6, 21.4) | 14.5 (12.3, 16.8) | 9.1 (6.6, 11.5) | <0.01 | 15.3 (13.0, 17.6) | 14.6 (12.3, 16.9) | 12.6 (10.3, 15.0) | 0.12 | 4.2 (2.2, 6.3) | 10.7 (8.6, 12.7) | 27.7 (25.7, 29.8) | <0.01 | ||

| Dairy products (g) | 118.9 (109.4, 128.3) | 116.2 (107.2, 125.2) | 105.6 (95.8, 115.3) | 0.07 | 114.3 (105.3, 123.4) | 118.6 (109.6, 127.6) | 107.7 (98.4, 116.9) | 0.32 | 126.1 (117.1, 135.0) | 110.2 (101.2, 119.2) | 104.3 (95.3, 113.4) | 0.01 | ||

| Eggs (g) | 61.1 (57.8, 64.4) | 64.3 (61.2, 67.4) | 57.7 (54.3, 61.0) | 0.18 | 46.3 (43.4, 49.2) | 60.0 (57.1, 62.8) | 76.7 (73.8, 79.7) | <0.01 | 67.3 (64.2, 70.3) | 60.8 (57.7, 63.9) | 55.0 (51.9, 58.1) | <0.01 | ||

| Fish/shellfish/mollusc (g) | 41.3 (36.4, 46.1) | 40.7 (36.1, 45.3) | 49.5 (44.5, 54.5) | 0.03 | 44.8 (40.1, 49.4) | 44.2 (39.5, 48.8) | 42.5 (37.7, 47.2) | 0.51 | 26.3 (22.0, 30.6) | 39.1 (34.8, 43.5) | 66.1 (61.7, 70.4) | <0.01 | ||

| Convenience foods/desserts (g) | 75.6 (70.4, 80.8) | 56.2 (51.2, 61.1) | 34.0 (28.7, 39.4) | <0.01 | 61.5 (56.3, 66.7) | 57.7 (52.6, 62.9) | 46.5 (41.2, 51.8) | <0.01 | 37.1 (32.2, 42.0) | 54.5 (49.6, 59.5) | 74.2 (69.2, 79.1) | <0.01 | ||

| Condiments (g) | 15.1 (13.1, 17.0) | 13.4 (11.6, 15.3) | 15.2 (13.2, 17.2) | 0.93 | 14.8 (12.9, 16.7) | 14.0 (12.1, 15.9) | 14.9 (13.0, 16.8) | 0.96 | 7.5 (5.8, 9.2) | 13.0 (11.2, 14.7) | 23.3 (21.5, 25.0) | <0.01 | ||

| Tea (ml) | 181.1 (127.5, 234.8) | 267.0 (216.1, 317.8) | 404.8 (349.7, 459.9) | <0.01 | 254.4 (202.3, 306.5) | 286.4 (234.7, 338.1) | 312.0 (259.0, 364.9) | 0.14 | 402.6 (352.1, 453.2) | 278.2 (227.3, 329.2) | 171.6 (120.5, 222.8) | <0.01 | ||

| Alcohol/beverages (ml) | 99.1 (78.0, 120.3) | 93.5 (73.4, 113.5) | 106.4 (84.7, 128.1) | 0.66 | 111.2 (91.0, 131.5) | 101.3 (81.2, 121.4) | 86.5 (65.9, 107.1) | 0.10 | 75.8 (55.9, 95.7) | 92.8 (72.8, 112.8) | 130.5 (110.4, 150.6) | <0.01 | ||

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval). ADA, animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol. †Characteristics presented in this table were adjusted for total energy intake.

Over a 3-year period, the associations between tertiles of dietary pattern scores and the changes in CVRFs are indicated in Table 5. The changes in TC and FBG were decreased with consumption of vegetable dietary pattern. In model 1, the mean (95% CI) of the changes in FBG over 3-year period across increasing tertiles of this dietary pattern scores were 0.10 (0.04, 0.16), 0.07 (0.01, 0.13), and −0.01 (−0.08, 0.05) (p for trend = 0.01). Moreover, in model 2, with additional adjustments, the mean (95% CI) of changed TC according to tertiles of this dietary pattern scores were 0.09 (0.01, 0.17), 0.02 (−0.06, 0.09), and −0.07 (−0.15, 0.01) (p for trend = 0.01) and the relationship between this pattern and the changes in FBG was essentially unchanged. On the other hand, ADA dietary pattern score was positively associated with the changes in SBP, DBP, TC and LDL-C. In model 1, the mean (95% CI) of changed SBP across increasing tertiles of this dietary pattern scores were −0.06 (−0.15, 0.03), −0.02 (−0.11, 0.07), and 0.07 (−0.02, 0.16) (p for trend = 0.01), and the mean (95% CI) of changed DBP were −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04), 0.10 (0.01, 0.21), and 0.14 (0.03, 0.24) (p for trend = 0.02). In addition, the mean (95% CI) of changed TC according to tertiles were −0.07 (−0.15, 0.01), 0.04 (−0.04, 0.11), and 0.08 (0.01, 0.15) (p for trend = 0.01), and the mean (95% CI) of changed LDL-C were −0.02 (−0.09, 0.06), 0.04 (−0.04, 0.11), and 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) (p for trend = 0.03). In model 2, the relationships of this pattern to the changes in DBP, TC and LDL-C were maintained, while the changes in SBP were not associated with this pattern anymore after further adjustments. Moreover, no statistically significant association between meat pattern and the changes in CVRFs was found in model 1 or model 2.

Table 5.

Associations between each dietary pattern score tertiles and the changes in cardiovascular risk factors during 3-year follow-up

| Cardiovascular risk factors | Vegetable pattern | Meat pattern | ADA pattern | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | Low | Middle | High | p trend | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1† | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.04 (–0.01, 0.08) | 0.65 | 0.01 (–0.03, 0.06) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.13) | 0.03 (–0.02, 0.07) | 0.70 | 0.01 (–0.03, 0.05) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) | 0.22 | ||

| Model 2‡ | 0.05 (0.01, 0.10) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) | 0.03 (–0.01, 0.08) | 0.51 | 0.02 (–0.03, 0.06) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.13) | 0.02 (–0.02, 0.07) | 0.85 | 0.01 (–0.04, 0.05) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) | 0.06 | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | –0.01 (–0.10, 0.08) | 0.02 (–0.07, 0.11) | –0.02 (–0.10, 0.07) | 0.96 | –0.03 (–0.12, 0.05) | –0.05 (–0.13, 0.04) | 0.07 (–0.02, 0.16) | 0.10 | –0.06 (–0.15, 0.03) | –0.02 (–0.11, 0.07) | 0.07 (–0.02, 0.16) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.03 (–0.06, 0.12) | 0.03 (–0.05, 0.12) | –0.07 (–0.17, 0.02) | 0.15 | –0.02 (–0.10, 0.07) | –0.04 (–0.13, 0.05) | 0.05 (–0.04, 0.14) | 0.36 | –0.06 (–0.15, 0.03) | –0.01 (–0.09, 0.08) | 0.05 (–0.04, 0.14) | 0.09 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.08 (–0.02, 0.19) | 0.10 (–0.01, 0.20) | –0.01 (–0.12, 0.10) | 0.24 | 0.13 (0.03, 0.24) | 0.03 (–0.08, 0.13) | 0.01 (–0.10, 0.12) | 0.40 | –0.07 (–0.18, 0.04) | 0.10 (0.01, 0.21) | 0.14 (0.03, 0.24) | 0.02 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.11 (–0.01, 0.22) | 0.11 (0.01, 0.21) | –0.05 (–0.16, 0.07) | 0.07 | 0.14 (0.04, 0.25) | 0.03 (–0.08, 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.11, 0.11) | 0.07 | –0.07 (–0.18, 0.04) | 0.10 (–0.01, 0.21) | 0.14 (0.04, 0.25) | 0.02 | ||

| TC (mmol/L) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.06 (–0.01, 0.14) | 0.01 (–0.06, 0.08) | –0.03 (–0.11, 0.04) | 0.08 | 0.01 (–0.07, 0.08) | 0.01 (–0.07, 0.07) | 0.03 (–0.04, 0.11) | 0.61 | –0.07 (–0.15, 0.01) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.11) | 0.08 (0.01, 0.15) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17) | 0.02 (–0.06, 0.09) | –0.07 (–0.15, 0.01) | 0.01 | 0.02 (–0.06, 0.09) | 0.01 (–0.07, 0.08) | 0.02 (–0.05, 0.10) | 0.90 | –0.07 (–0.15, 0.01) | 0.04 (–0.03, 0.12) | 0.07 (–0.01, 0.15) | 0.01 | ||

| TG (mmol/L) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.07) | –0.01 (–0.07, 0.05) | 0.01 (–0.06, 0.06) | 0.87 | 0.01 (–0.06, 0.06) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.09) | –0.03 (–0.09, 0.03) | 0.60 | –0.05 (–0.11, 0.01) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.08) | 0.02 (–0.04, 0.08) | 0.21 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.07) | –0.01 (–0.07, 0.05) | –0.01 (–0.07, 0.06) | 0.69 | 0.01 (–0.06, 0.06) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.09) | –0.04 (–0.10, 0.02) | 0.37 | –0.05 (–0.11, 0.01) | 0.03 (–0.03, 0.08) | 0.02 (–0.05, 0.08) | 0.17 | ||

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.08 (0.01, 0.16) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.12) | 0.01 (–0.08, 0.08) | 0.71 | 0.05 (–0.03, 0.13) | –0.02 (–0.10, 0.06) | 0.08 (0.01, 0.16) | 0.68 | –0.03 (–0.11, 0.06) | 0.10 (0.02, 0.18) | 0.05 (–0.04, 0.13) | 0.08 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.11 (0.02, 0.19) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.12) | –0.03 (–0.12, 0.05) | 0.18 | 0.06 (–0.02, 0.14) | –0.01 (–0.09, 0.06) | 0.07 (–0.01, 0.16) | 0.81 | –0.03 (–0.11, 0.05) | 0.11 (0.03, 0.19) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.12) | 0.21 | ||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16) | 0.06 (–0.02, 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.08, 0.06) | 0.07 | 0.05 (–0.03, 0.12) | 0.05 (–0.02, 0.13) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.11) | 0.83 | –0.02 (–0.09, 0.06) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.11) | 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) | 0.03 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.09 (0.01, 0.17) | 0.06 (–0.02, 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.09, 0.07) | 0.09 | 0.05 (–0.03, 0.12) | 0.05 (–0.02, 0.12) | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.11) | 0.86 | –0.01 (–0.09, 0.06) | 0.03 (–0.04, 0.10) | 0.12 (0.05, 0.20) | 0.02 | ||

| FBG (mmol/L) | ||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | 0.10 (0.04, 0.16) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.13) | –0.01 (–0.08, 0.05) | 0.01 | 0.01 (–0.05, 0.07) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15) | 0.05 (–0.01, 0.11) | 0.33 | 0.02 (–0.05, 0.08) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.12) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14) | 0.43 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.10 (0.03, 0.16) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.12) | –0.01 (–0.08, 0.06) | 0.04 | –0.01 (–0.07, 0.06) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15) | 0.07 (0.01, 0.13) | 0.14 | 0.02 (–0.05, 0.08) | 0.05 (–0.01, 0.12) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15) | 0.16 | ||

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval). ADA, animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBG, fasting blood glucose. †Model 1: associations adjusted for age. ‡Model 2: model 1 with additional adjustments for total energy intake, the longitudinal change of BMI, education level, smoking status, drinking status and family history of cardiovascular disease.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the effects of dietary patterns on the longitudinal changes in CVRFs in apparently healthy Chinese women. We identified three major dietary patterns in this study which were labeled “vegetable”, “meat” and “ADA” dietary pattern. The results suggested that consumption of vegetable dietary pattern was associated with decreased the changes in TC and FBG, whereas consumption of ADA pattern was associated with increased the changes in DBP, TC and LDL-C. The meat dietary pattern was not associated with the longitudinal changes in CVRFs.

Consistent with findings from this study, dietary pattern characterized by high vegetable intake was associated with lower levels of CVRFs in many studies. Among Western populations, many studies have reported that the vegetable pattern may reduce the levels of CVRFs.(15,20–22) Similarly, in Japanese populations, vegetable pattern was beneficially related to CVRFs.(23,24) Furthermore, a meta-analysis that focused on dietary patterns and CVRFs confirmed this association too.(25)

There are several candidate mechanistic hypotheses that could account for this association. The food items prominent in this dietary pattern are kinds of vegetables, fruits, legumes, grains, cereals, nuts, and tea. Increasing evidences have suggested that higher intake of vegetables and fruits play an important role in decreasing weight, FBG, TC and preventing CVD.(26–29) Besides, eating a variety of whole grain foods and legumes are beneficial in management of blood sugar has also been demonstrated.(30) Plant-based foods provide a range of nutrients and different bioactive compounds including phytochemicals, vitamins, minerals, and fibers.(31) More than 5,000 individual dietary phytochemicals have been identified in these food mentioned above. Previous result has confirmed that total intake of flavonoids is inversely associated with the LDL-C and TC concentrations.(32) Flavonoids have an antioxidant effect is probably by the donation of a single electron to the radical resulting in the formation of a semiquinone radical, which can donate a further electron to form the orthoquinone.(33) Additionally, plant-based diets are also high in fiber, which may delay gastric emptying, slow food digestion and absorption, then reduce appetite and food consumption, thereby contributing to improve insulin sensitivity and lower serum lipid concentrations.(34,35) Furthermore, lots of studies have also shown that vitamins and minerals, like vitamin C, vitamin E, potassium, and magnesium which are abundant in vegetable are also inversely associated with CVRFs.(36–38)

On the other hand, the role of ADA pattern in cardiovascular disease is less consistent. This pattern comprised some items similar to Western dietary pattern which was reported previously. In the Strong Heart Study, followers of the Western pattern had higher LDL-C and SBP.(14) Similarly, a recent report among Chinese older adults indicated that individuals who adopted Western dietary pattern had an increased risk of having higher levels of SBP, DBP and TG.(39) While, the EPIC-NL cohort study in Dutch showed no association.(40) Anyway, the relationships between this pattern and changes in CVRFs may be explained by some potential mechanisms. For instance, the ADA pattern is high in animal offal, such as liver, kidney, etc., which are rich in cholesterol. Previous studies have demonstrated that dietary cholesterol is one of the major determinants of TC.(41,42) One systematic review and meta-analysis have also confirmed that dietary cholesterol statistically significantly increased both serum TC and LDL-C.(43) Moreover, condiments group consisting of salted vegetable, pickle and fermented bean curd also has significant factor loading in this pattern, diet high in condiments including sodium has been generally accepted as a risk factor for increasing BP.(44) Meanwhile, ADA pattern is rich in convenience foods and desserts, alcohol and beverages, the negative effects of those foods upon the CVRFs have already been clarified.(12,45–47) In the present study, we observed that subjects in the highest tertile of ADA pattern were more likely to be younger. Previous studies conducted among Chinese have also suggested that subjects with higher adherence to the dietary pattern, which was characterized by a high intake of animal offal, desserts, dim sum and alcohol, tended to have higher education and income level, but less physical activity.(48–49) The younger people as the backbone of developing China, are often with great pressure from work and life, neglecting the importance of healthy diet. Our findings may provide tangible dietary advice to them.

In addition, we found no association between the meat dietary pattern and CVRFs, although previous studies have shown that a high intake of animal protein (especially red meat) is significantly associated with an elevated level of CVRFs.(50) However, our result is in line with the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study, which found no association between the frequent intake of meat and CVD, either.(51) The possible explanation of this finding maybe the plant foods including rice and vegetables moderate the negative effect of the meat products or the animal foods displace the consumption of more beneficial plant foods.

The present study has several strengths, including the 3-year longitudinal design, the extensive dietary assessments consisting of 81 food items, and the questionnaires were collected through face-to-face interviews. Despite these strengths, certain limitations need to be addressed. Firstly, reliability of memory is recognized as the core problem in dietary measurement, we collected the diet data in 2014 and chose the subjects who did not changed their eating habits during the past three years, therefore, the effects of recall bias cannot be avoided in the present study. Secondly, residual confounding, which is common in observational studies, although we have adjusted for a wide range of potentially confounding covariates, there may be other factors affecting results for the limited data. Finally, because of the small sample size in men, a statistically significant analysis could not be performed, and we cannot report results on the effects of dietary patterns on CVRFs in men.

In summary, our findings would support the notion that greater adherence to vegetable dietary pattern may reduce the longitudinal changes in TC and FBG, whereas greater adherence to ADA dietary pattern may increase the longitudinal changes in DBP, TC and LDL-C among apparently healthy Chinese women. More studies are required to establish a better understanding of potential causal mechanisms, and provide further evidence on this understudied topic.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate and thank all subjects who participated in the study and the staff of the Health Education and Guidance Center of Heping District in Tianjin for their assistance. This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Support Program (No. 2012BAI02B02).

Abbreviations

- ADA

animal offal-dessert-and-alcohol

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CVRFs

cardiovascular risk factors

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- FBS

fasting blood glucose

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MUFA

monounsaturated fatty acid

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- SFA

saturated fatty acid

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng Y, Stein R, Kwan T, et al. Evolving cardiovascular disease prevalence, mortality, risk factors, and the metabolic syndrome in China. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:491–497. doi: 10.1002/clc.20605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang ZJ, Liu J, Ge JP, Chen L, Zhao ZG, Yang WY, ; China National Deabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study Group Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor in the Chinese population: the 2007–2008 China National Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders Study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:213–220. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu D, Gupta A, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor clustering among the adult population of China: results from the International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia (InterAsia) Circulation. 2005;112:658–665. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.515072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu SS, Kong LZ, Gao RL, et al. Outline of the report on cardiovascular disease in China, 2010. Biomed Environ Sci. 2012;25:251–256. doi: 10.3967/0895-3988.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Zhai F, Du S, Popkin B. Dynamic shifts in Chinese eating behaviors. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhai F, Wang H, Du S, et al. Prospective study on nutrition transition in China. Nutr Rev. 2009;67 Suppl 1:S56–S61. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batis C, Sotres-Alvarez D, Gordon-Larsen P, Mendez MA, Adair L, Popkin B. Longitudinal analysis of dietary patterns in Chinese adults from 1991 to 2009. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1441–1451. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao W, Chen J. Implications from and for food cultures for cardiovascular disease: diet, nutrition and cardiovascular diseases in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001;10:146–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-6047.2001.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnell CJ, Elosua R. Cardiovascular risk factors. Insights from Framingham Heart Study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:299–310. (in Spanish) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro-Martínez MG, Bolado-García VE, Landa-Anell MV, Liceaga-Cravioto MG, Soto-González J, López-Alvarenga JC. Dietary trans fatty acids and its metabolic implications. Gac Med Mex. 2010;146:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astrup A, Dyerberg J, Selleck M, Stender S. Nutrition transition and its relationship to the development of obesity and related chronic diseases. Obes Rev. 2008;9 Suppl 1:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eilat-Adar S, Mete M, Fretts A, et al. Dietary patterns and their association with cardiovascular risk factors in a population undergoing lifestyle changes: The Strong Heart Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tourlouki E, Matalas AL, Panagiotakos DB. Dietary habits and cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly populations: a review of evidence. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:319–330. doi: 10.2147/cia.s5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, et al. Major dietary patterns and cardiovascular risk factors from childhood to adulthood. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:218–225. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507691831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman GR, Streiner DL. PDQ Statistics. Hamilton, Ont.: B.C. Decker; 2003. pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia Q, Xia Y, Zhang Q, et al. Dietary patterns are associated with prevalence of fatty liver disease in adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:914–921. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Wang G, Pan X. China Food Composition Table. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2002. pp. 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kesse-Guyot E, Ahluwalia N, Lassale C, Hercberg S, Fezeu L, Lairon D. Adherence to Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of metabolic syndrome: a 6-year prospective study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peñalvo JL, Oliva B, Sotos-Prieto M, et al. Greater adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern is associated with improved plasma lipid profile: the Aragon Health Workers Study cohort. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2015;68:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen J, Wilmot KA, Ghasemzadeh N, et al. Mediterranean dietary patterns and cardiovascular health. Annu Rev Nutr. 2015;35:425–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-011215-025104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimazu T, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japan: a prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:600–609. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niu K, Momma H, Kobayashi Y, et al. The traditional Japanese dietary pattern and longitudinal changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in apparently healthy Japanese adults Eur J Nutr 2015. DOI: 10.1007/s00394-015-0844-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastorini CM, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1299–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuda N, Miura K, Okayama A, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease in Japan: a 24-year follow-up of the NIPPON DATA80 Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:482–488. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartley L, Igbinedion E, Holmes J, et al. Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD009874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Moslehi N, Bastan S, Azizi F. Colors of fruits and vegetables and 3-year changes of cardiometabolic risk factors in adults: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:1215–1219. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkins DJ, Popovich DG, Kendall CW, et al. Effect of a diet high in vegetables, fruit, and nuts on serum lipids. Metabolism. 1997;46:530–537. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venn BJ, Mann JI. Cereal grains, legumes and diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1443–1461. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu RH. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:384S–392S. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai Y, Watanabe S, Kimira M, Shimoi K, Mochizuki R, Kinae N. Dietary intakes of flavonols, flavones and isoflavones by Japanese women and the inverse correlation between quercetin intake and plasma LDL cholesterol concentration. J Nutr. 2000;130:2243–2250. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.9.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yap S, Qin C, Woodman OL. Effects of resveratrol and flavonols on cardiovascular function: Physiological mechanisms. Biofactors. 2010;36:350–359. doi: 10.1002/biof.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang C, Liu S, Solomon CG, Hu FB. Dietary fiber intake, dietary glycemic load, and the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2223–2230. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandalia M, Garg A, Lutjohann D, von Bergmann K, Grundy SM, Brinkley LJ. Beneficial effects of high dietary fiber intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1392–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jha P, Flather M, Lonn E, Farkouh M, Yusuf S. The antioxidant vitamins and cardiovascular disease. A critical review of epidemiologic and clinical trial data. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:860–872. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-11-199512010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Iso H, Ohira T, Date C, Tamakoshi A, ; JACC Study Group Associations of dietary magnesium intake with mortality from cardiovascular disease: the JACC study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1378. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun J, Buys NJ, Hills AP. Dietary pattern and its association with the prevalence of obesity, hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:3956–3971. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110403956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stricker MD, Onland-Moret NC, Boer JM, et al. Dietary patterns derived from principal component- and k-means cluster analysis: long-term association with coronary heart disease and stroke. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattson FH, Erickson BA, Kligman AM. Effect of dietary cholesterol on serum cholesterol in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972;25:589–594. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keys A. Serum cholesterol response to dietary cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;40:351–359. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berger S, Raman G, Vishwanathan R, Jacques PF, Johnson EJ. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:276–294. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy V, Sridhar A, Machado RF, Chen J. High sodium causes hypertension: evidence from clinical trials and animal experiments. J Integr Med. 2015;13:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez-González MÁ, Martin-Calvo N. The major European dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:265–271. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanhope KL, Medici V, Bremer AA, et al. A dose-response study of consuming high-fructose corn syrup-sweetened beverages on lipid/lipoprotein risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:1144–1154. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bogl LH, Pietiläinen KH, Rissanen A, et al. Association between habitual dietary intake and lipoprotein subclass profile in healthy young adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Yuan JM, Gross MD, Pereira MA. Dietary patterns and mortality in a Chinese population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:877–883. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.086124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shu L, Zheng PF, Zhang XY, et al. Association between dietary patterns and the indicators of obesity among Chinese: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2015;7:7995–8009. doi: 10.3390/nu7095376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stettler N, Murphy MM, Barraj LM, Smith KM, Ahima RS. Systematic review of clinical studies related to pork intake and metabolic syndrome or its components. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:347–357. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S51440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harriss LR, English DR, Powles J, et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular mortality in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:221–229. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.