Abstract

Purpose

Acute pyelonephritis (APN) is a serious bacterial infection that can cause renal scarring in children. Early identification of APN is critical to improve treatment outcomes. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a prognostic marker of many diseases, but it has not yet been established in urinary tract infection (UTI). The aim of this study was to determine whether NLR is a useful marker to predict APN or vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 298 pediatric patients (age≤36 months) with febrile UTI from January 2010 to December 2014. Conventional infection markers (white blood cell [WBC] count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP]), and NLR were measured.

Results

WBC, CRP, ESR, and NLR were higher in APN than in lower UTI (P<0.001). Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that NLR was a predictive factor for positive dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) defects (P<0.001). The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was high for NLR (P<0.001) as well as CRP (P<0.001) for prediction of DMSA defects. NLR showed the highest area under the ROC curve for diagnosis of VUR (P<0.001).

Conclusion

NLR can be used as a diagnostic marker of APN with DMSA defect, showing better results than those of conventional markers for VUR prediction.

Keywords: Urinary tract infections, Pyelonephritis, Vesico-ureteral reflux, Child, Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

Introduction

An acute urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common bacterial infection that causes an inflammatory response and may lead to serious morbidity in infants and children1). Approximately 1% of boys and 3–5% of girls have at least one UTI during childhood, and 30–50% of these children will have at least one recurrence2). It may be not easy to recognize UTI in infants and children, particularly those younger than 3 years, because the presenting symptoms and signs are nonspecific1).

UTI often occurs as a simple bladder infection, but can also involve the kidneys, which is termed an acute pyelonephritis (APN). APN is an infection of the renal parenchyma, which can lead to renal scar formation and increased risk of hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and ultimately end-stage renal disease (ESRD)3,4). Consequently, prompt differential diagnosis of APN and timely initiation of the appropriate antibiotics are the important keys to the management of UTIs.

There are several studies examining potential accurate, noninvasive biomarkers for the ability to discriminate APN in children5,6,7,8). Several parameters of the systemic inflammatory response, including level of white blood cell (WBC) count, procalcitonin (PCT), c-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), were not accurate enough to confidently differentiate8,9). However, there have been several studies showing that neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a measure of systemic bacterial inflammation and it has been used as a guide to prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia, ischemic heart disease, and several types of cancer10). Thus, NLR may serve as a useful diagnostic indicator and prognostic factor of APN, but there are no studies on the usefulness of NLR in children with UTIs.

NLR of the patients admitted is easily calculated and immediately available based on a complete blood count. In the present study, we aimed to validate the value of NLR that can be used as a substantial inflammatory marker of APN and predictive marker of complications in young children with febrile UTI.

Materials and methods

1. Patients and inclusion criteria

Data from 298 pediatric patients less than 36 months of age with febrile UTI admitted to Severance Children's Hospital from January 2010 to December 2014 were retrospectively analyzed. The diagnosis of a first-time febrile UTI for entry into this study was based on the following criteria: (1) a fever of ≥38℃, (2) a pyuria (≥5 WBCs per high-power field), (3) a positive urine culture collected from a clean-catch or catheterized specimen (defined as growth of a single organism to ≥100,000 colony-forming units/mL), (4) no previous history of UTI, kidney or bladder disease. Imaging studies, including renal ultrasonography (USG), dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan and voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), were performed.

Patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of defects as determined by DMSA scans. VUR was defined as the retrograde passage of urine from the bladder into ureters or kidney by VCUG study11,12). The VCUG was performed after end of the antibiotics treatment.

2. Data analysis

Clinical data, such as age, sex, and duration of fever were recorded. Before initiation of antibiotic treatment, blood was sampled for laboratory analyses, including a complete blood cell count (CBC), WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, ESR, CRP. The NLR was then calculated using neutrophils/lymphocytes.

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected by antecubital venipuncture into vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, NJ, USA) containing tripotassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. CBCs were done within 1 hour after the blood samples were drawn. CBC analysis was performed using the Advia 2120i automated analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL, USA). CRP levels were measured by the latex-enhanced turbidimetric assay method using a Hitachi 7600 P module (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). ESR levels were measured by the TEST 1 (Alifax, Padova, Italy). Strict quality control procedures were adopted.

Imaging studies including USG, DMSA, and VCUG were performed in febrile patients with UTI. After the patients were admitted due to UTI, USG and DMSA scan were performed within the first 5 days. VCUG was done within 4 weeks after two-week antibiotics therapy.

Urine collection was obtained with sterile and sealed urine collection bags or clean urethral catheters for febrile infants. These urinary examinations were done upon admission to the hospital before any administration of fluid therapies or antibiotics intravenously.

3. Statistical methods

IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to compare variables. Independent t test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution, in addition to descriptive statistics expressed as mean±standard deviation. Chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Correlation analysis was carried out to determine the relationship between two variables by Spearman correlation. The discriminative ability of each biomarker for APN was evaluated by plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the biomarkers. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to find independent predictive factors for positive DMSA defects and present VUR in UTI patients. All differences were considered significant at a value of P<0.05.

4. Ethics statement

The institutional review board (IRB) and Research Ethics Committee of Yonsei University Severance Hospital approved this study. The IRB exempted informed consents because of the nature of retrospective study. Personal identifiers were completely removed and the data were analyzed anonymously. Our study was conducted according to the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Results

The clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of the patients are showed in Table 1. Among the 298 children with a first episode of a febrile UTI, 163 tested positive for a DMSA defect (116 males and 47 females), and 135 did not show a DMSA defect (98 males and 37 females) (P=0.785). There were no differences regarding the age between of the groups (P=0.149). The WBC, NLR, ESR, and CRP levels were compared between these two groups. For all measurements (WBC, NLR, ESR, and CRP), values were significantly higher in the group of APN with DMSA defect (P<0.001), suggesting that these values may help us distinguish DMSA defect of APN in children.

Table 1. Comparison of variables between patients with and without renal cortical defects detected by DMSA scans.

| Variable | DMSA defect (+) (n=163) |

DMSA defect (–) (n=135) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mo) | 4.3±4.0 | 4.9±3.1 | 0.149 |

| Sex | 0.785 | ||

| Male:female | 116:47 | 98:37 | |

| WBC (/mm3) | 17,285±6,341 | 14,026±5,338 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 2.5±2.3 | 1.4±1.0 | <0.001 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 44.8±31.6 | 32.4±24.3 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 71.7±68.6 | 31.5±26.8 | <0.001 |

| USG abnormality | 124 (76.1) | 82 (60.7) | 0.004 |

| VUR | 70 (42.9) | 14 (10.4) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

DMSA, dimercaptosuccinic acid; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; USG, ultrasonography; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux.

Next, renal USG results were compared between positive DMSA defect and negative DMSA defect groups. Abnormal USG results correlated significantly with renal cortical defect and they were detected in 76.1% of the APN patients (P=0.004). There was a significant difference in the incidence of VUR among children with and without renal lesions. Among 84 VUR patients, 70 (42.9%) were found to have VUR in positive renal scans, but only 14 (10.4%) had VUR in negative renal scans (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Renal USG abnormalities were divided into 5 groups. The most common finding was pelvic dilation, which was seen in 78 patients. Among those patients, DMSA defect (P=0.086) was seen in 36. The second common finding was hydronephrosis (57 patients), and 42 patients of them were showed a significant defect on DMSA scan (P=0.002). Dilatation of the ureter was seen in 31 patients, and increased focal vascularity of the kidney cortex was seen in 30 of those patients, which means a presence focal APN. We could not find any significant association with DMSA defect (P=1.000 and P=0.034). The group of others was 2 patients with polycystic kidney disease and 1 patient with a horseshoe kidney (Table 2).

Table 2. Renal ultrasonography abnormalities according to the renal cortical defects detected by DMSA scans.

| Variable | DMSA defect (+) (n=163) |

DMSA defect (–) (n=135) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 44 (27.0) | 55 (40.7) | 0.014 |

| Pelvic dilatation | 36 (22.1) | 42 (31.1) | 0.086 |

| Hydronephrosis | 42 (25.8) | 15 (11.1) | 0.002 |

| Ureter dilatation | 17 (10.4) | 14 (10.4) | 1.000 |

| Increased focal vascularities | 22 (13.5) | 8 (5.9) | 0.034 |

| Others | |||

| PKD | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Horseshoe kidney | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1.000 |

Values are presented as number (%).

DMSA, dimercaptosuccinic acid; PKD, polycystic kidney disease.

We divided our patients according to the VUR grading system of the International Reflux Study12) and grouped them to mild (grades 1–2) and severe (grades 3–5). In cases with bilateral VUR, grading was done by the more severe side. We analyzed mild and severe VUR groups according to the renal USG findings (Table 3). The renal USG findings included normal, pelvic dilatation, hydronephrosis, ureter dilatation, increased focal vascularities, and the others. There was significant difference between mild and severe VUR only in normal USG group (P=0.004).

Table 3. Renal ultrasonography abnormalities according to the VUR grade.

| Variable | Mild VUR (n=214) |

Severe VUR (n=84) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 82 (38.3) | 17 (20.2) | 0.004 |

| Pelvic dilatation | 58 (27.1) | 20 (23.8) | 0.661 |

| Hydronephrosis | 33 (15.4) | 24 (28.6) | 0.014 |

| Ureter dilatation | 18 (8.4) | 13 (15.5) | 0.091 |

| Increased focal vascularities | 23 (10.7) | 7 (8.3) | 0.670 |

| Others | |||

| PKD | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0.282 |

| Horseshoe kidney | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | 0.079 |

Values are presented as number (%).

VUR grade: mild, 1–2; severe, 3–5.

VUR, vesicoureteral reflux; PKD, polycystic kidney disease.

We checked if there was any relationship of NLR and CRP between the groups of VUR grades. Upon an independent sample test, NLR and CRP both have shown no significant association with VUR grades (P=0.616 and P=0.081).

Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to test each parameter as an independent predictor of positive DMSA scans. These results showed that CRP (odds ratio [OR], 1.022; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.013–1.030; P<0.001) and NLR (OR, 1.603; 95% CI, 1.263–2.035; P<0.001) were independent predictive factors for positive DMSA defects in UTI patients (Table 4).

Table 4. Multiple logistic regression analysis of laboratory parameters associated with renal cortical defects detected by dimercaptosuccinic acid scans.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (/mm3) | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.676 |

| Neutrophil (/mm3) | 1.012 | 0.972–1.055 | 0.556 |

| NLR | 1.603 | 1.263–2.035 | <0.001 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 0.998 | 0.986–1.011 | 0.807 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.022 | 1.013–1.030 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

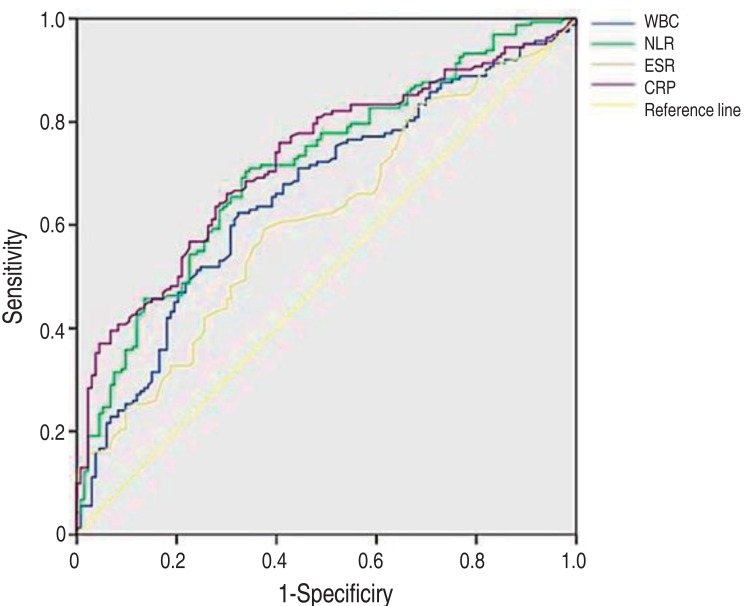

The diagnostic properties of the various inflammatory markers were examined for their predictability of a defect as detected by a DMSA scan using ROC curves. The median area under the ROC curve was 0.660 for WBC (95% CI, 0.598–0.723; P<0.001), 0.713 for NLR (95% CI, 0.654–0.771; P<0.001), 0.611 for ESR (95% CI, 0.547–0.675; P<0.001), and 0.726 for CRP (95% CI, 0.669–0.783; P<0.001) (Table 5, Fig. 1). These results suggest that CRP is the most predictable value of a DMSA defect and NLR is also a good predictor equally to CRP.

Table 5. Receiver operating characteristic analysis of inflammatory markers that predict positive dimercaptosuccinic acid scans.

| Variable | Area under curve | Standard error | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (/mm3) | 0.660 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 0.598–0.723 |

| NLR | 0.713 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.654–0.771 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 0.611 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 0.547–0.675 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.726 | 0.269 | <0.001 | 0.669–0.783 |

CI, Confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Fig. 1. Receiver operating characteristic curves of C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) for differentiating between positive and negative results from dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scans. The area under curves of NLR and CRP show a significant correlation to DMSA scans positive for a defect (P<0.001).

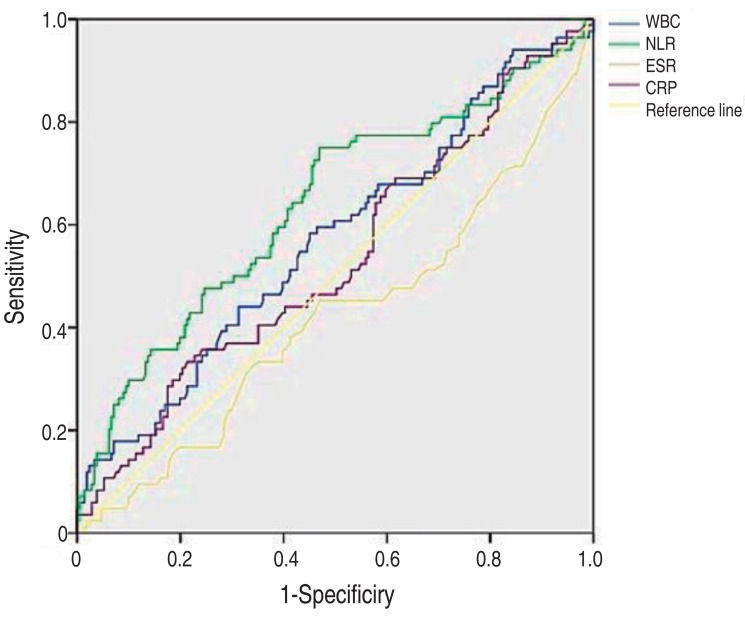

Finally, the diagnostic properties of the various inflammatory markers were examined for their predictability of VUR (Table 6, Fig. 2). The median area under the ROC curve was 0.570 for WBC (95% CI, 0.496–0.643; P=0.061), 0.638 for NLR (95% CI, 0.565–0.711; P<0.001), 0.419 for ESR (95% CI, 0.344–0.494; P=0.03), and 0.533 for CRP (95% CI, 0.459–0.607; P=0.374). These results indicate that NLR is the most predictable value of the presence of VUR than others.

Table 6. Receiver operating characteristic analysis of inflammatory markers that predict the presence of vesicoureteral reflux.

| Variable | Area under curve | Standard error | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (/mm3) | 0.570 | 0.038 | 0.061 | 0.496–0.643 |

| NLR | 0.638 | 0.037 | <0.001 | 0.565–0.711 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 0.419 | 0.038 | 0.030 | 0.344–0.494 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.533 | 0.038 | 0.374 | 0.459–0.607 |

CI, Confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Fig. 2. Receiver operating characteristic curves of C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) for the prediction of vesicoureteral reflux.

Discussion

UTI is a common bacterial infection in childhood1). Most pediatric hospitals have therapeutic experience with this disease. In some children with UTI, the infection is localized to the bladder, while bacteria ascend to the kidney (APN) in others5). Only children with upper UTI are at risk for developing renal scarring, which affects the long-term prognosis of kidney diseases such as hypertension, CKD, or ESRD3,4). Therefore, prompt detection of complications such as renal scarring and VUR is important to the management of UTIs in children.

Currently, two diagnostic methods are in place to detect renal parenchymal involvement: DMSA scan and USG13). The DMSA scan is a very sensitive detection method and considered as a superior tool for assessment of the extent and progress of renal scarring over USG11). However, DMSA has several limitations, including availability in all centers, higher cost, and radiation exposure9). Additionally, the test is required sedation process during the scanning for young children.

Because of the limitations described above, many studies have been conducted to predict renal complication of APN with noninvasive and widely used biomarkers, such as PCT, CRP, ESR, and WBC. In this study, high CRP levels correlated with defects found on a positive DMSA scan and the presence of VUR. However, several other studies have shown that these markers could not reliably distinguish renaI complications13). In one study, CRP was not sufficient as a predictive value, with sensitivity of 83%14). In another study, CRP had a sensitivity of 100%, but a specificity of 18.5%15). Such results are not adequate to meet expectations. In one comprehensive review in 2015, Shaikh et al.9) examined the usefulness of PCT, CRP, and ESR for the renal scarring in UTI with 24 relevant studies, of which 17 provided data. They found that none of the tests were accurate enough to allow clinicians to confidently detect renaI scarring9).

Our study shows a significant difference in the incidence of VUR among children with and without renal lesions (42.9% vs. 10.4%). According to the systematic overview of 33 studies that examined the prognosis in UTI children, approximately 25% of children with an initial UTI had VUR, and 57% of them had DMSA scan findings consistent with APN16). Children with VUR were significantly more likely to develop APN and renal scarring compared to children without VUR16). Although we suggest that the identification of VUR is important, a VCUG is not recommended in the first UTI event. A VCUG is indicated only that if USG reveals hydronephrosis or renal scarring that could suggest either VUR or obstructive uropathy17). The VCUG procedure poses a significant burden to patients and physicians due to its invasive nature and risk of radiation exposure.

The aim of this study was to present the NLR as a practical biomarker that could predict APN. It is clear that there are important association between the NLR and bacterial infection such as pneumonia, sepsis, and systemic inflammatory response18,19,20). In this setting, increased NLR outperformed conventional markers, such as WBC, neutrophil counts, and CRP, as a useful biomarker to detect bacteremia10,19,20). WBC differential counts undergo a number of rapid, serial changes in response to surgical stress, systemic inflammation, or sepsis21). Characteristically, total WBCs and neutrophils increase and lymphocytes decrease, particularly in a bacterial infection by the classic cellular shift22). The underlying mechanism of neutrophilia is the activity of growth factors on stem cells to stimulate neutrophil generation22). The induction of the tumor necrosis factor family occurs early in the inflammatory response; these receptors are expressed on lymphocytes and cause lymphocyte apoptosis. Lymphocytopenia has been reported as a diagnostic marker of bacterial infection19,23). Therefore, NLR can play a special role as a predictive marker of bacterial infection compared to neutrophilia or lymphocytopenia alone18).

This study revealed a significant correlation between elevated NLR and DMSA defect of APN. The inflammatory markers (WBC, ESR, CRP, and NLR) were all investigated, and our study showed that CRP had the highest AUC value of 0.726, followed by NLR (0.713), WBC (0.660), and ESR (0.611) as determined on the ROC curves (P<0.001). On the other hand, NLR was more associative than CRP in the multiple logistic regression analysis (OR: 1.603 vs. 1.022, P<0.001) (Table 2). Furthermore, the highest association between NLR and presence of VUR was found using the ROC curves to calculate the AUC value of 0.638, which was greater than that for WBC (0.570), CRP (0.533), and ESR (0.419) (P<0.001).

In conclusion, this report is the first study that presents the usefulness of NLR as a value to predict DMSA defect and VUR in young children with febrile UTI. NLR is a simple, cheap, and easy parameter of inflammation because it can be measured in almost all laboratories. The data from this study suggest that NLR was correlated significantly with DMSA defect in pediatric patients with UTI. Furthermore, NLR may be a reliable marker for the prediction of VUR.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health, editors. Urinary tract infection in children: diagnosis, treatment and long-term management. NICE clinical guideline, No. 54. London: RCOG Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Copp HL, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL. National ambulatory antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric urinary tract infection, 1998-2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1027–1033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paintsil E. Update on recent guidelines for the management of urinary tract infections in children: the shifting paradigm. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25:88–94. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835c14cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson SH, Eklof O, Lins LE, Wikstad I, Winberg J. Long-term prognosis of post-infectious renal scarring in relation to radiological findings in childhood-: a 27-year follow-up. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00856822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leroy S, Fernandez-Lopez A, Nikfar R, Romanello C, Bouissou F, Gervaix A, et al. Association of procalcitonin with acute pyelonephritis and renal scars in pediatric UTI. Pediatrics. 2013;131:870–879. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koufadaki AM, Karavanaki KA, Soldatou A, Tsentidis Ch, Sourani MP, Sdogou T, et al. Clinical and laboratory indices of severe renal lesions in children with febrile urinary tract infection. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103:e404–e409. doi: 10.1111/apa.12706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouguila J, Khalef I, Charfeddine B, Ben Rejeb M, Chatti K, Limam K, et al. Comparative study of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in the severity diagnosis of pyelonephritis in children. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2013;61:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tekin M, Konca C, Gulyuz A, Uckardes F, Turgut M. Is the mean platelet volume a predictive marker for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children? Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19:688–693. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaikh N, Borrell JL, Evron J, Leeflang MM. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD009185. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009185.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowsby R, Gomes C, Jarman I, Lisboa P, Nee PA, Vardhan M, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte count ratio as an early indicator of blood stream infection in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:531–534. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Xu H, Zhou L, Cao Q, Shen Q, Sun L, et al. Accuracy of early DMSA scan for VUR in young children with febrile UTI. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e30–e38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tullus K. Vesicoureteric reflux in children. Lancet. 2015;385:371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pecile P, Miorin E, Romanello C, Falleti E, Valent F, Giacomuzzi F, et al. Procalcitonin: a marker of severity of acute pyelonephritis among children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e249–e254. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gervaix A, Galetto-Lacour A, Gueron T, Vadas L, Zamora S, Suter S, et al. Usefulness of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein rapid tests for the management of children with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:507–511. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolkin V, Koren A, Raz R, Colodner R, Sakran W, Halevy R. Procalcitonin as a marker of acute pyelonephritis in infants and children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00467-001-0790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaikh N, Ewing AL, Bhatnagar S, Hoberman A. Risk of renal scarring in children with a first urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1084–1091. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128:595–610. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon NB, Son C, Um SJ. Role of the neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio in the differential diagnosis between pulmonary tuberculosis and bacterial community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33:105–110. doi: 10.3343/alm.2013.33.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyllie DH, Bowler IC, Peto TE. Relation between lymphopenia and bacteraemia in UK adults with medical emergencies. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:950–955. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.017335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jager CP, van Wijk PT, Mathoera RB, de Jongh-Leuvenink J, van der Poll T, Wever PC. Lymphocytopenia and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio predict bacteremia better than conventional infection markers in an emergency care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14:R192. doi: 10.1186/cc9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turak O, Ozcan F, Isleyen A, Basar FN, Gul M, Yilmaz S, et al. Usefulness of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio to predict in-hospital outcomes in infective endocarditis. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1672–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts: rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2001;102:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala A, Lomas JL, Grutkoski PS, Chung S. Fas-ligand mediated apoptosis in severe sepsis and shock. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:593–600. doi: 10.1080/00365540310015656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]