Abstract

Purpose

Urge urinary incontinence is a major problem, especially in the elderly, and to our knowledge the underlying mechanisms of disease and therapy are unknown. We used biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training and functional brain imaging (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to investigate cerebral mechanisms, aiming to improve the understanding of brain-bladder control and therapy.

Materials and Methods

Before receiving biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training functionally intact, older community dwelling women with urge urinary incontinence as well as normal controls underwent comprehensive clinical and bladder diary evaluation, urodynamic testing and brain functional magnetic resonance imaging. Evaluation was repeated after pelvic floor muscle training in those with urge urinary incontinence. Functional magnetic resonance imaging was done to determine the brain reaction to rapid bladder filling with urgency.

Results

Of 65 subjects with urge urinary incontinence 28 responded to biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training with 50% or greater improvement of urge urinary incontinence frequency on diary. However, responders and nonresponders displayed 2 patterns of brain reaction. In pattern 1 in responders before pelvic floor muscle training the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the adjacent supplementary motor area were activated as well as the insula. After the training dorsal anterior cingulate cortex/supplementary motor area activation diminished and there was a trend toward medial prefrontal cortex deactivation. In pattern 2 in nonresponders before pelvic floor muscle training the medial prefrontal cortex was deactivated, which changed little after the training.

Conclusions

In older women with urge urinary incontinence there appears to be 2 patterns of brain reaction to bladder filling and they seem to predict the response and nonresponse to biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training. Moreover, decreased cingulate activation appears to be a consequence of the improvement in urge urinary incontinence induced by training while prefrontal deactivation may be a mechanism contributing to the success of training. In nonresponders the latter mechanism is unavailable, which may explain why another form of therapy is required.

Keywords: urinary bladder, overactive, brain, urinary incontinence, urge, magnetic resonance imaging, biofeedback, psychology

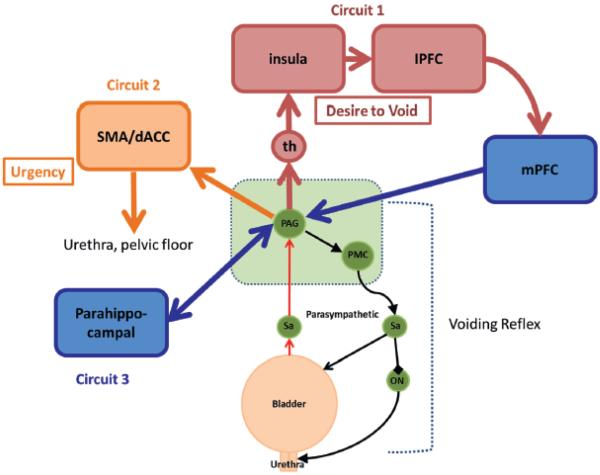

PREVALENT, morbid and costly, UUI is a major problem for older adults. Although generally attributed to DO, its actual causes remain uncertain.1,2 Despite many treatment advances in the last 50 years mechanisms of disease and therapy (behavioral or pharmacological) remain unclear and available treatments are still not curative. Therefore, we determined factors that predict or mediate the response to behavioral treatment, reasoning that predictors should help identify possible UUI phenotypes with different responses to treatment while mediators of improvement might reveal the mechanism of therapy.3 We expected that this new knowledge would help enhance treatment efficacy. In a previous study of PFMT,3 which is a widely recommended behavioral treatment for UUI,4,5 we found that urodynamic parameters neither predicted nor mediated the response to treatment. The only exception was the strength and velocity of DO, which predicted a poor response but only in subjects with elicitable DO. Having excluded most peripheral (urodynamic) aspects as convincing predictors or mediators, in the current study we focused on central (brain) control of the LUT. The LUT normally alternates between periods of urine storage and shorter periods of voiding.1,6 During storage as the bladder fills, bladder sensation normally increases from none through first desire to void to strong desire to void7 until it is interrupted by voluntary voiding. In UUI brain control is abnormal, that is sensation is altered and voiding may occur involuntarily. According to a provisional model of brain-bladder control developed in the last decade 3 neural circuits help maintain continence by suppressing the spinobulbospinal voiding reflex at its terminus in the PAG (fig. 1).1,2,6,8,9 Circuit 1 involves the mPFC, and its afferent and efferent pathways, possibly including the insula, while circuit 2 involves the dACC (midcingulate) and the adjacent SMA, and circuit 3 may involve subcortical regions such as the parahippocampal complex.10 In strictly normal subjects such as the controls in this study circuits 1 and 2 are not significantly activated during storage but circuit 1 (mPFC) is activated during voluntary voiding.11,12 In UUI subjects we expected that there would be abnormalities in brain activation provoked by bladder filling and postulated that these abnormalities would predict the response to therapy. We also expected that treatment associated changes in brain activation might occur in those who responded well to therapy but not in nonresponders. The direction of such changes must be correct, eg normalization suggests that change is a consequence or cause of symptom improvement.3,11,12 The current study focused on 2 circuits (fig. 1), that is circuit 1 involving the mPFC and the insula, and circuit 2 involving the dACC/SMA. Specifically we expected the insula, the seat of visceral interoception,13 to be activated by bladder filling. We expected the dACC and the SMA to be significantly activated during urgency, producing the motor output that hinders leakage.14,15 We also expected that the mPFC, which is involved with executive control of behavior, would show deactivation during the storage phase.10 Furthermore, we postulated that dACC/SMA activation would revert toward normal after successful treatment (ie in responders) and mPFC deactivation would become less pronounced. The postulated direction of the 2 changes implies that they are consequences of therapeutic improvement. However, if the direction proved incorrect, this might reveal a mechanism of therapy. Although the pontine micturition center is an important part of the control mechanism, we did not include this in our a priori hypotheses for this study, choosing to focus on higher level control. We studied older women with UUI, using PFMT to improve bladder control and fMRI to reveal associated changes in cerebral activity. We also included a group of age matched normal controls. Men were excluded from analysis to avoid confounding by prostatic pathology.

Figure 1.

Simplified working model of brain/bladder control system. Voiding reflex incorporates PAG and pontine micturition center (PMC) in brain stem (green areas), which control contraction and relaxation of bladder and urethral muscles via sacral parasympathetic regions (Sa) and Onuf nucleus (ON). This reflex is controlled by 3 cerebral neural circuits. Circuit 1 involves thalamus (th), insula and lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC) with mPFC regulating executive control of voiding. Circuit 2 involves dACC and SMA, which together generate urgency sensation and provide motor output to pelvic floor/sphincter mechanism. Parahippocampal complex is part of putative subcortical circuit 3. Red and yellow areas indicate regions typically activated by bladder filling. Blue areas indicate regions deactivated by bladder filling. Adapted from de Groat et al.1

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and Subjects

Functionally intact, community dwelling women were recruited by newspaper advertisements. Eligibility included age 60 years or greater, urge predominant incontinence with 5 or more UUI episodes per week for 3 months or longer by self-report, 1 or more episode on 3-day bladder diary and demonstrable DO on prePFMT urodynamic evaluation. We excluded those with impaired mobility or cognition (MMSE score less than 27/30 or inability to follow study procedures), a clinically apparent neurological lesion, prolapse beyond the hymen, interstitial cystitis, spinal cord injury, history of pelvic radiation, or advanced uterine or bladder cancer, multiple sclerosis, urethral obstruction, urinary retention (post-void residual urine greater than 200 ml), medical instability or expected medication change during the study, any condition requiring intravenous antibacterial prophylaxis before urodynamics, history of claustrophobia or fear of scanner, or metallic or electronic implant incompatible with MRI. Continent controls were recruited with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria but without UUI by self-report or bladder diary and with no DO on urodynamics or in the scanner. Subjects provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00177541).

Evaluation

Evaluation included medical and voiding/incontinence history, physical examination, 3-day bladder diary,16 comprehensive urodynamic evaluation with vigorous provocation of potential DO3 and functional brain imaging. Each was performed before and after PFMT. The percentage reduction in incontinence episodes on the diary was used to define3 responders to therapy who showed a 50% or greater reduction. The cut point was chosen a priori to be simple and likely to yield similar numbers of responders and nonresponders.3 Demographic, clinical and urodynamic data p values were determined by the t-test and the chi-square test.

PFMT Intervention

PFMT comprised 2 biofeedback sessions followed by 2 sessions of verbal coaching and instruction during 8 to 12 weeks administered by an experienced practitioner.17 Using pelvic floor electrodes for biofeedback subjects were taught correct exercise technique and urge suppression strategies, practiced at home and kept daily bladder records.3 The most effective elements of therapy according to the patients were urge suppression (quick pelvic floor muscle contractions when urgency was felt) and pelvic floor muscle exercises.18

Functional MRI

As in our previous fMRI series19,20 with the subject supine in a MAGNETOM_ Trio 3 Tesla scanner we recorded a structural brain image followed by repeat blocks of functional brain scans (fMRI with standard echo planar imaging pulse sequence) with an almost empty and a full bladder while monitoring intravesical pressure urodynamically to detect DO.19 All reported results were obtained from the block with the fullest bladder, or during urgency or strong desire to void but without concurrent DO. As described previously in detail18,19 we used an infusion/withdrawal paradigm (4 _ 10-second infusion with full bladder) to repeatedly reproduce urgency or strong desire to void in the scanner, signaled by a pushbutton.19,20 DO and leakage blocks were excluded and most participants were continent while supine. After standard preprocessing with SPM5 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/), including image realignment to correct for head motion, brain responses were determined by comparing the fMRI BOLD (blood oxygenation level dependent) signal during infusion and withdrawal.19 Activation meant that the signal was greater during infusion than during withdrawal, that is the converse of deactivation. Single subject responses with t values calculated voxel by voxel were entered into second level group analyses. We used the 1-sample, 2-sample or paired t-test as appropriate with small volume correction to limit calculation to 3 spherical ROIs, each with a radius of 18 mm and centered at MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) coordinates (insula [38, 16, 6], dACC/SMA [4, 14, 42] and mPFC [4, 50, 14], respectively).21,22 Group results were first assessed voxel by voxel over all subjects using a threshold of p = 0.05 uncorrected for multiple comparisons. Table 1 shows the number of suprathreshold voxels in each ROI. Statistical significance was then assessed for the resulting clusters with correction for multiple comparisons (cluster level corrected p <0.05, table 1).23 Responses that met only a lower level of significance were noted as trends. Because values were calculated on a voxel-by-voxel basis across each subject, they could not be used directly to infer differences between ROIs (table 1). For example, prePFMT minus postPFMT values were not equal to the difference between prePFMT and post-PFMT values, and zero denoted no voxels above the threshold to remove nonsignificant activation. The total number of 2 × 2 × 2mm voxels in each ROI was approximately 3,000 and so the number of activated or deactivated voxels could not exceed this value.

Table 1.

Second level (group) analysis of number of deactivated and activated (suprathreshold) voxels in 3 predetennined ROIs

| ROI (MNI coordinates [x, y, z]) | PrePFMT (ROI)* | Post-PFMT (ROI)* | PrePFMT – Post-PFMT |

|---|---|---|---|

| dACC/SMA [4, 14, 42]: | |||

| All UUI | 1,072 | 742 | 7 |

| Responders | 2,600† (I) | 536 (IV) | 1,650† |

| Nonresponders | 0 | 275 | 0 |

| Responders – nonresponders | 2,521‡ | 11 | – |

| Controls | 0 | – | – |

| Controls – responders | 0 | – | – |

| Controls – nonresponders | 38 | – | – |

| Rt insula [38, 16, 6]: | |||

| All UUI | 573 | 775 | 9 |

| Responders | 2,025† (II) | 1,539† | 111 |

| Nonresponders | 0 | 42 | 0 |

| Responders – nonresponders | 975 | 934 | – |

| Controls | 242 | – | – |

| Controls – responders | 4 | – | – |

| Controls – nonresponders | 0 | – | – |

| mPFC [4, 50, 14]: | |||

| All UUI | −916 | −2,218† | 105 |

| Responders | 0 | −351 (III) | 754 |

| Nonresponders | −2,229‡ (V) | −2,349† (VI) | 0 |

| Responders – nonresponders | 2,325 | 1,078 | – |

| Controls | 0 | – | – |

| Controls – responders | 0 | – | – |

| Controls – nonresponders | 1,027 | – | – |

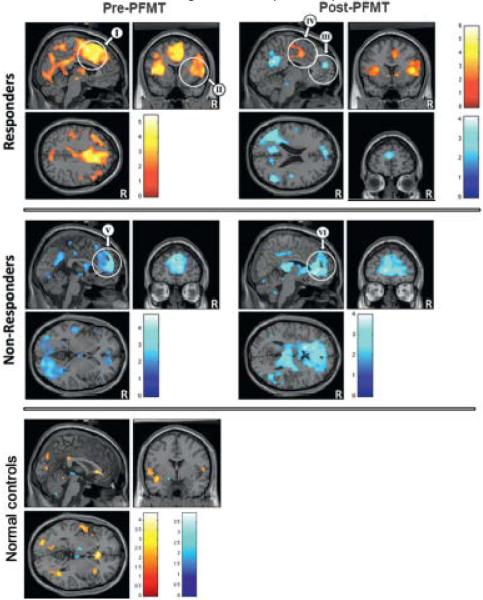

ROIs I to V (fig. 2).

Significant (p <0.05) at corrected cluster level.

Trend toward significance (p <0.05) at uncorrected cluster level.

Statistical Power

Estimating power to detect a difference in brain activation between responders and nonresponders using cluster level tests of significance is complex. This was the primary outcome (table 1 and fig. 2). However, our experience and published approximations suggested that groups of 20 participants should be adequate for reliable results.24,25 We aimed to obtain complete data on 60 subjects to easily achieve such numbers in subgroups.

Figure 2.

PrePFMT and post-PFMT activation (yellow/red areas) and deactivation (blue areas) in responders, nonresponders and normal controls with no PFMT. In responders activation and deactivation pattern changed after intervention, showing more deactivation. Nonresponders showed marked prePFMT deactivation, which changed little after PFMT. White circles indicate 3 predetermined spherical ROIs with 18 mm radius, including III, V and VI in mPFC, I and IV in dACC/SMA, and II in right insula (table 1). Color bars indicate Student t-test values.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 65 UUI subjects completed the protocol. Three subjects were excluded because of technically unacceptable fMRI results, leaving 62 for analysis. Mean age was 71.6 years overall, and 69.0 and 73.7 years in the 28 responders and 34 nonresponders to therapy, respectively, which was significantly different (p = 0.04, table 2). Mean age of the 11 controls was 64.0 years, significantly younger than patients with UUI (p = 0.01).

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical and urodynamic data on UUI subjects

| All UUI | Responders | Nonresponders | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts* | 62 | 28 | 34 | 11 |

| Mean ± SD age | 71.6 ± 9.2 | 69.0 ± 9.0 | 73.7 ± 9.2† | 64.0 ± 5.6‡ |

| Mean ± SD MMSE/30 | 29.6 ± 0.9 | 29.8 ± 0.5 | 29.4 ± 1.1 | 29.O ± 1.8 |

| Mean ± SD body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 5.9 | 29.0 ± 5.3 | 30.9 ± 6.0 | 28.3 ± 4.8 |

| % Depression history (No. pts) | 34 (2l) | 25 (7) | 41 (14) | 18 (2) |

| % Diabetes mellitus (No. pts) | 24 (15) | 21 (6) | 26 (9) | 0§ |

| % Transient ischemic accident/ministroke + no residual (No. pts) | 8 (5) | 7 (2) | 9 (3) | 9 (1) |

| Mean ± SD parity | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 1.8 |

| No. anticholinergic medication | 6 | 0 | 6† | 0 |

| Mean ± SD max cystometric capacity (ml) | 486 ± 225 | 451 ± 247 | 511 ± 209 | 549 ± 161 |

| Mean ± SD 1st filling sensation (ml) | 203 ± 135 | 166 ± 121 | 223 ± 140 | 213 ± 93 |

| Mean ± SD strong desire to void (ml) | 355 ± 157 | 327 ± 120 | 374 ± 176 | 471 ± 151‡ |

| Mean ± SD DO: | – | |||

| Detrusor pressure at max flow (cm H2O) | 23.7 ± 16.7 | 18.9 ± 12.O | 27.0 ± 18.7† | |

| Velocity (cm H2O/sec) | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | |

| Mean ± SD UUI frequency/24 hrs: | – | |||

| PrePFMT | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 2.4 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | |

| Post-PFMT | 1.9 ± 1.8∥ | 0.7 ± 0.8∥ | 3.0 ± 1.6¶,** | |

| Mean ± SD sphincter squeeze (cm H2O): | ||||

| PrePFMT | 25.3 ± 16.7 | 22.9 ± 16.1 | 26.9 ± 17.0 | 27.1 ± 16.8 |

| Post-PFMT | 19.8 ± 16.3¶ | 15.8 ± 16.3 | 22.4 ± 16.0 | – |

| Mean ± SD bladder neck squeeze (cm H2O): | ||||

| PrePFMT | 27.9 ± 17.1 | 26.9 ± 18.8 | 28.5 ± 15.9 | 33.3 ± 19.0 |

| Post-PFMT | 22.6 ± 14.5¶ | 20.5 ± 13.1¶ | 24.1 ± 15.5 | – |

All patients were fully mobile.

Significantly different vs responders (p = 0.05).

Significantly different vs all UUI (p <0.05).

p = 0.07.

Significantly different vs prePFMT(p <0.0001).

Significantly different vs prePFMT (p = 0.05).

Significantly different vs responders (p <0.0001).

PFMT Effect on Incontinence

When determining the PFMT effect on incontinence, 3 with PFMT the mean frequency of UUI episodes decreased from 3.5 to 1.9 per 24 hours (p<0.0001). Of 62 subjects 28 (46%) were responders, that is they showed a 50% or greater improvement in UUI frequency. PrePFMTUUI frequency was 3.5 per 24 hours in responders and nonresponders (table 2). UUI frequency decreased from 3.5 to 0.7 episodes per 24 hours in responders and from 3.5 to 3.0 per 24 hours in nonresponders. Nine of 62 subjects (15%) were dry on the end study diary.

Differences between Responders and Nonresponders

Responders and nonresponders to PFMT did not differ significantly in diabetes, parity, mobility or MMSE score (table 2).26 Those on anticholinergic medication had been on the medication at least 6 months and they did not change the dose or cease medication during the study. Most neurological conditions were ruled out by our exclusion criteria but 7% to 9% of subjects in each subgroup had a history of a possible transient ischemic accident or ministroke without residual effects. As in our previous study3 urodynamic measurements showed few significant differences but maximum detrusor pressure during DO was again higher in nonresponders, although DO velocity was not. Voluntary urethral squeeze pressure did not differ between responders and nonresponders but tended to diminish after PFMT.

fMRI Observations

PrePFMT. PrePFMT with a full bladder and rapid bladder filling provoked a weak brain reaction in normal controls (table 1 and fig. 2). However, in subjects with UUI it tended to activate the dACC/ SMA and deactivate the mPFC. Stratification into those who would later respond or fail to respond to PFMT revealed that responders and nonresponders displayed different patterns of brain reaction even before PFMT. In responders the dACC/SMA and the insula were activated (table 1 and fig. 2). In nonresponders the mPFC and parts of the posterior brain were deactivated (fig. 2). Post-PFMT. Among UUI subjects the pattern of brain reaction remained similar to that before PFMTexcept mPFC deactivation became significant (table 1). Among nonresponders the pretreatment pattern of deactivation remained essentially unchanged after PFMT (fig. 2). Among responders dACC/SMA activation was significantly less after PFMT (cluster level corrected p <0.05) while the mPFC showed a trend toward deactivation (voxel-wise uncorrected p = 0.001 and corrected p = 0.41, fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Figure 2 encapsulates the main findings of this study. 1) In contrast to normal controls, in patients with UUI there are significant patterns of brain activation and deactivation before PFMT. 2) These patterns differ strikingly between responders and nonresponders to therapy (table 1). The prePFMT pattern of brain activation or deactivation may predict the clinical response to PFMT treatment and may describe a disease phenotype. 3) In nonresponders to therapy the pattern of deactivation barely changes after PFMT. However, responders show marked changes in brain deactivation and activation, implying that these changes are causes (mediators) or consequences of therapeutic improvement.

Predictors

Before PFMT the reaction to a threat of leakage in nonresponders is strong deactivation of the mPFC and some posterior parts of the brain (circuit 1, figs. 1 and 2). Because of its location in the executive brain, mPFC deactivation likely reflects an executive willed decision to suppress voiding, perhaps via the return pathway to the PAG (fig. 1). However, in those who prove responsive the threat of leakage triggers a different prePFMT reaction involving circuit 2 (figs. 1 and 2). Activity in the dACC and the adjacent SMA increases, probably accompanied by urgency27 and by tightening the sphincter14 so that leakage can be temporarily averted. This pattern of responses may represent a panic reaction to threatened leakage.19 It is not observed in normal controls (table 1).

Mediators

In nonresponders UUI severity and the corresponding pattern of deactivation are essentially unchanged by treatment as described. However, in responders when UUI severity is reduced following PFMT, dACC/SMA activation is also significantly reduced. This change is in the direction of normalization, suggesting a compensatory reaction to the diminished severity of UUI. It is not a mechanism of therapy. Furthermore, in responders a trend toward deactivation in the mPFC and the posterior brain emerges de novo after PFMT (fig. 2). This change is in the direction of increased abnormality since normal controls do not show it (table 1). Therefore, increased mPFC deactivation likely mediates the PFMT induced improvement in UUI, suggesting that the causal mechanism of PFMT therapy involves stronger executive control of the LUT. Indeed, urge suppression is part of PFMT that is specifically aimed at increasing bladder control and it is highly valued by patients.18

Why do Nonresponders Fail to Respond?

In nonresponders deactivation is close to its ceiling value even before PFMT (table 1 and fig. 2). Therefore, PFMT cannot augment it effectively and a nonresponse is inevitable. The question remains of why in some patients the deactivation mechanism is used before PFMT while in others the dACC/SMA is activated. One possibility is that there are 2 distinct UUI phenotypes that differ in the response to PFMT as well as in the characteristics of DO (table 2).3 A plausible alternative is that there may be 1 phenotype that is expressed differently according to the severity of an underlying abnormality such as white matter disease. Thus, in subjects with mild disease the dACC/SMA may be activated as a compensatory reaction to threatened UUI. Under instruction by a PFMT practitioner or if the abnormality is severe enough to affect the brain ability to compensate, the mPFC may deactivate. However, the effectiveness of this maneuver is limited by the ceiling value.

Limitations

To our knowledge this is the largest fMRI study of UUI. Nonetheless, some analyses had limitedstatistical power to show the modest effects of PFMT. The control group was small and incompletely age matched, reflecting the difficulty of finding normal older volunteers. This initial series limited participation to women with DO receiving 1 intervention to isolate the relevant brain mechanisms. A study of men and the inclusion of less severe forms of UUI (ie without DO) and other interventions would be useful in the future to ensure the applicability of this work to wider populations and interventions. Further study is required of posterior brain deactivation outside the predetermined ROIs (fig. 2). Deactivation is an important but controversial element of this interpretation. It occurs mainly in circuit 1, part of the well-known default mode network28 that is active at rest but deactivated if attention is required for some cognitive event. Thus, deactivation of circuit 1 may signify that bladder control demands conscious attention.

CONCLUSIONS

Two main cortical circuits (prefrontal and midcingulate) are involved in bladder control. Correspondingly there are 2 patterns of brain response to bladder filling. They appear to predict the success or failure of behavioral treatment, thus, confirming the clinical impression18 that there is a distinct group of older women with therapy resistant UUI. One of these patterns (midcingulate activation) is a compensatory reaction to a threat of leakage. The other (prefrontal deactivation) may be a mechanism of biofeedback (PFMT) therapy. If so, some UUI patients already make maximal use of this mechanism prior to intervention and, therefore, they cannot respond to this treatment. They seem to need a different therapy directed at the underlying abnormality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Werner Schaefer performed urodynamics and discussed the study. Linda Organist performed biofeedback. Andrew Murrin assisted with computer analysis and maintenance. Megan Kramer performed clinical aspects. Mary Jo Sychak screened the subjects.

Study received University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approval. Supported by NIH R01 (AG20629).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- dACC

dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

- DO

detrusor overactivity

- fMRI

functional MRI

- LUT

lower urinary tract

- MMSE

Mini Mental State Examination

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PAG

periaqueductal gray

- PFMT

biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training

- ROI

region of interest

- SMA

supplementary motor area

- UUI

urge urinary incontinence

REFERENCES

- 1.de Groat WC, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N. Neural control of the lower urinary tract. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:327. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:453. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick NM, Perera S, Tadic S, et al. What predicts and what mediates the response of urge urinary incontinence to biofeedback? Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:408. doi: 10.1002/nau.22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:213. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann KE, McPheeters ML, Biller DH, et al. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 187, Report 09eE017. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville: 2009. Treatment of Overactive Bladder in Women. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths DJ, Fowler CJ. The micturition switch and its forebrain influences. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;207:93. doi: 10.1111/apha.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths D, Tadic SD, Schaefer W, et al. Cerebral control of the bladder in normal and urgeincontinent women. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kavia RB, Dasgupta R, Fowler CJ. Functional imaging and the central control of the bladder. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:27. doi: 10.1002/cne.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tadic SD, Griffiths D, Schaefer W, et al. Brain activity underlying impaired continence control in older women with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;31:652. doi: 10.1002/nau.21240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blok BF, Sturms LM, Holstege G. Brain activation during micturition in women. Brain. 1998;121:2033. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.11.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blok BF, Willemsen AT, Holstege G. A PET study on brain control of micturition in humans. Brain. 1997;120:111. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhtz-Buschbeck JP, van der Horst C, Wolff S, et al. Activation of the supplementary motor area (SMA) during voluntary pelvic floor muscle contractionsdan fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2007;35:449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seseke S, Baudewig J, Kallenberg K, et al. Voluntary pelvic floor muscle controldan fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1399. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bright E, Cotterill N, Drake M, et al. Developing and validating the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire bladder diary. Eur Urol. 2014;66:294. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1995. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley MA, Organist L. Streamlining biofeedback for urge incontinence. Urol Nurs. 2014;34:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths D, Derbyshire S, Stenger A, et al. Brain control of normal and overactive bladder. J Urol. 2005;174:1862. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177450.34451.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tadic SD, Griffiths D, Murrin A, et al. Brain activity during bladder filling is related to white matter structural changes in older women with urinary incontinence. Neuroimage. 2010;51:1294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tadic SD, Griffiths D, Schaefer W, et al. Abnormal connections in the supraspinal bladder control network in women with urge urinary incontinence. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffiths DJ, Tadic SD, Schaefer W, et al. Cerebral control of the lower urinary tract: how agerelated changes might predispose to urge incontinence. Neuroimage. 2009;47:981. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friston KJ, Holmes A, Poline JB, et al. Detecting activations in PET and fMRI: levels of inference and power. Neuroimage. 1996;4:223. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desmond JE, Glover GH. Estimating sample size in functional MRI (fMRI) neuroimaging studies: statistical power analyses. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;118:115. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy K, Garavan H. An empirical investigation into the number of subjects required for an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2004;22:879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dosenbach NU, Visscher KM, Palmer ED, et al. A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron. 2006;50:799. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths D. Imaging bladder sensations. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:899. doi: 10.1002/nau.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]