Abstract

AIM: To investigate the diagnostic validity and therapeutic value of lumbar facet joint interventions in managing chronic low back pain.

METHODS: The review process applied systematic evidence-based assessment methodology of controlled trials of diagnostic validity and randomized controlled trials of therapeutic efficacy. Inclusion criteria encompassed all facet joint interventions performed in a controlled fashion. The pain relief of greater than 50% was the outcome measure for diagnostic accuracy assessment of the controlled studies with ability to perform previously painful movements, whereas, for randomized controlled therapeutic efficacy studies, the primary outcome was significant pain relief and the secondary outcome was a positive change in functional status. For the inclusion of the diagnostic controlled studies, all studies must have utilized either placebo controlled facet joint blocks or comparative local anesthetic blocks. In assessing therapeutic interventions, short-term and long-term reliefs were defined as either up to 6 mo or greater than 6 mo of relief. The literature search was extensive utilizing various types of electronic search media including PubMed from 1966 onwards, Cochrane library, National Guideline Clearinghouse, clinicaltrials.gov, along with other sources including previous systematic reviews, non-indexed journals, and abstracts until March 2015. Each manuscript included in the assessment was assessed for methodologic quality or risk of bias assessment utilizing the Quality Appraisal of Reliability Studies checklist for diagnostic interventions, and Cochrane review criteria and the Interventional Pain Management Techniques - Quality Appraisal of Reliability and Risk of Bias Assessment tool for therapeutic interventions. Evidence based on the review of the systematic assessment of controlled studies was graded utilizing a modified schema of qualitative evidence with best evidence synthesis, variable from level I to level V.

RESULTS: Across all databases, 16 high quality diagnostic accuracy studies were identified. In addition, multiple studies assessed the influence of multiple factors on diagnostic validity. In contrast to diagnostic validity studies, therapeutic efficacy trials were limited to a total of 14 randomized controlled trials, assessing the efficacy of intraarticular injections, facet or zygapophysial joint nerve blocks, and radiofrequency neurotomy of the innervation of the facet joints. The evidence for the diagnostic validity of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks with at least 75% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements was level I, based on a range of level I to V derived from a best evidence synthesis. For therapeutic interventions, the evidence was variable from level II to III, with level II evidence for lumbar facet joint nerve blocks and radiofrequency neurotomy for long-term improvement (greater than 6 mo), and level III evidence for lumbosacral zygapophysial joint injections for short-term improvement only.

CONCLUSION: This review provides significant evidence for the diagnostic validity of facet joint nerve blocks, and moderate evidence for therapeutic radiofrequency neurotomy and therapeutic facet joint nerve blocks in managing chronic low back pain.

Keywords: Chronic low back pain, Lumbar facet joint pain, Lumbar discogenic pain, Intraarticular injections, Lumbar facet joint nerve blocks, Lumbar facet joint radiofrequency, Controlled diagnostic blocks, Lumbar facet joint

Core tip: This review summarizes diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of chronic low back pain of facet joint origin. Even though multiple high quality diagnostic accuracy studies are available, there is room for further studies to confirm accuracy. These studies are key for the universal acceptance of facet joint nerve blocks of the lumbosacral spine as the gold standard. Deficiencies continue with therapeutic interventions. Lumbar radiofrequency neurotomy studies have shown contradicting results with short-term follow-ups. There is limited high quality literature for lumbar facet joint nerve blocks, and the available literature contains contradictory findings in multiple trials of intraarticular injections.

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain is a common health problem with increasing prevalence, health challenges, and economic impact[1-20]. Studies indicate that low back pain is the number one cause contributing to most years lived with disability in 2010 in the United States and globally[1,2]. In addition, work-related low back pain continues to be an important cause of disability[3]. The global burden of low back pain has a point prevalence of 9.4% of the population, with severe chronic low back pain but a lack of lower extremity pain accounting for 17% of cases, and of low back pain with leg pain 25.8%[2]. Low back pain increased 162% in North Carolina, from 3.9% in 1992 to 10.2% in 2006[4]. Treatment of chronic low back pain has yielded mixed results and the substantial economic and health impact has raised concerns among the public-at-large, policy-makers, and physicians[6-19]. The large increase in treatment types and rapid escalation in health care costs may be attributed to multiple factors, including the lack of an accurate diagnosis and various treatments that do not have appropriate evidence of effectiveness.

Numerous structures in the lower back may be responsible for low back and/or lower extremity pain, including lumbar intervertebral discs, facet joints, sacroiliac joints, and nerve root dura, and may be amenable to diagnostic measures such as imaging and controlled diagnostic blocks[10,21-29]. Other structures also capable of transmitting pain, including ligaments, fascia, and muscles, may not be diagnosed with accuracy with any diagnostic techniques[29]. Disc-related pathology with disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and radiculitis are diagnosed with reasonable ease and accuracy leading to definitive treatments[30]. However, low back pain from discs (without disc herniation), lumbar facet joints, and sacroiliac joints is difficult to diagnose accurately by noninvasive measures including imaging[10,21-35]. Consequently, no gold standard is generally acknowledged for diagnosing low back pain, irrespective of the source being facet joint(s), intervertebral disc(s), or sacroiliac joint(s), despite the fact that lumbar facet joints, the paired joints that stabilize and guide motion in the spine, have been frequently implicated.

Based on neuroanatomy, neurophysiologic, biomechanical studies, and controlled diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks, lumbar facet joints have been recognized as a potential cause of low back pain as well as referred lower extremity pain in patients who have chronic low back pain[10,22-35]. Lumbar facet joints are well innervated by the medial branches of the dorsal rami, with presence of free and encapsulated nerve endings as well as nerves containing substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide[10,35-38]. While there are many causes for pain in the facet joints, mechanical injury and inflammation of the facet joints have produced persistent pain in experimental settings[39-45]. Further, the high prevalence of facet joint osteoarthritis has been illustrated in numerous studies[46-49]. Nonetheless, attempts to make the diagnosis of lumbar facet joint pain by history, identification of pain patterns, physical examination, and imaging techniques better have shown low accuracy and utility[10,22-29,35]. It has been proposed that controlled diagnostic blocks may be the only means to diagnose lumbar facet joint pain with reasonable accuracy, although controversy continues regarding the diagnostic accuracy of controlled local anesthetic blocks[10,21-29,31,32,35,50-53].

With appropriate diagnosis, accurate and evidence-based treatments may be expected to achieve reasonable outcomes; however, the disadvantages of controlled local anesthetic blocks, apart from discussions on their accuracy, include invasiveness, expenses, and difficulty in interpretation, occasionally making them problematic in routine clinical practice as a primary diagnostic modality. Various systematic reviews have assessed the value and validity of various diagnostic maneuvers including diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks[10,28,29,32,35].

Therapeutic interventions include conservative modalities and interventional techniques and occasionally surgical interventions[10,33,54-73]. Conservative management includes drug therapy, chiropractic manipulation, physical therapy, and biopsychosocial rehabilitation. However, there have not been any trials reported in the literature that studied conservative management[10,54-67] in confirmed lumbar facet joint pain or discogenic pain[74,75]. The literature regarding pain of presumed facet joint origin has involved interventional techniques using intraarticular injections, facet joint nerve blocks, and various neurolytic techniques, including injection of neurolytic solutions, radiofrequency neurotomy, and cryoneurolysis. However, as with diagnostic accuracy studies of facet joint nerve blocks, therapeutic interventions have met with favor, skepticism, and critiques[10,15,50-55,69-74].

The aim of this systematic review is to assess the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks and the therapeutic effectiveness of multiple interventional techniques based on a best evidence synthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was conducted utilizing the review process derived from evidence-based systematic reviews and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[76-83].

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Diagnostic accuracy studies and RCTs evaluating accuracy and efficacy managing lumbar facet joint pain were included. Patients above 18 years of age with chronic lumbar facet joint pain of at least 3 mo duration after failure of previous pharmacotherapy, physical therapy, and exercise therapy were included for interventional pain management. Types of included studies were all RCTs and diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks appropriately performed with proper technique under fluoroscopy or computed tomography guidance.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures included pain relief as the primary criterion for diagnostic accuracy studies concordant with the local anesthetic used and the ability to perform previously painful movements. The primary outcome parameter for RCTs of efficacy was pain relief with short-term defined up to 6 mo and long-term defined as longer than 6 mo with functional improvement as the secondary outcome measure.

Literature search

Literature searches were performed utilizing PubMed from 1966, EMBASE from 1980, Cochrane library, United States National Guideline Clearinghouse, previous systematic reviews and cross references, and any other trials available from any source in all languages from all countries, through March 2015.

Search strategy

The search strategy included a review of the literature through March 2015 and emphasized chronic low back pain, facet or zygapophysial joint pain, cryoneurolysis, neurolytic injections, chronic lumbar facet joint pain, and selected studies meeting inclusion criteria.

The search terminology was as follows: (((((((((((((((((chronic low back pain) OR chronic back pain) OR disc herniation) OR discogenic pain) OR facet joint pain) OR herniated lumbar discs) OR nerve root compression) OR lumbosciatic pain) OR postlaminectomy) OR lumbar surgery syndrome) OR radicular pain) OR radiculitis) OR sciatica) OR spinal fibrosis) OR spinal stenosis) OR zygapophysial)) AND (((((((facet joint[tw]) OR zygapophyseal[tw]) OR zygapophysial[tw]) OR medial branch block[tw]) OR diagnostic block[tw]) OR radiofrequency[tw]) OR intraarticular[tw]).

Data collection and analysis

At least 2 of the review authors independently in an unblinded standardized manner performed each search and assessed outcome measures. The searches were combined to obtain a unified search strategy.

Methodological quality or validity assessment

At least 2 of the review authors independently assessed the criteria for inclusion for methodological quality assessment and then performed the methodological quality assessment. Authors with a perceived conflict of interest for any manuscript, either with authorship or any other aspect, were recused from reviewing those manuscripts.

For diagnostic accuracy studies, all articles were assessed based on the quality appraisal of reliability studies checklist, which has been validated[80]. All randomized trials were assessed for methodological quality utilizing Cochrane review criteria[78] and Interventional Pain Management Techniques - Quality Appraisal of Reliability and Risk of Bias Assessment (IPM-QRB) criteria[79].

Summary measures

Summary measures for diagnostic accuracy studies included at least 50% pain relief with an ability to perform previously painful movements as the criterion standard, whereas for RCTs, summary measures included a 50% or more reduction of pain in at least 40% of the patients or at least a 3 point decrease in pain scores.

Outcomes and analysis of evidence

Outcomes of the studies of diagnostic accuracy were assessed for prevalence and false-positive rates when available. For therapeutic efficacy, the short- and long-term outcomes were assessed. For diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy studies, 5 levels of evidence were utilized as shown in Table 1, varying from level I with the highest evidence with multiple relevant high quality RCTs, or multiple high quality diagnostic accuracy studies, to level V with minimal evidence and results based on consensus. Any disagreement among authors was resolved by a third author or by consensus.

Table 1.

Modified grading of qualitative evidence with best evidence synthesis for diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic interventions

| Level I | Evidence obtained from multiple relevant high quality randomized controlled trials |

| or | |

| Evidence obtained from multiple high quality diagnostic accuracy studies | |

| Level II | Evidence obtained from at least one relevant high quality randomized controlled trial or multiple relevant moderate or low quality randomized controlled trials |

| or | |

| Evidence obtained from at least one high quality diagnostic accuracy study or multiple moderate or low quality diagnostic accuracy studies | |

| Level III | Evidence obtained from at least one relevant moderate or low quality randomized controlled trial study |

| or | |

| Evidence obtained from at least one relevant high quality non-randomized trial or observational study with multiple moderate or low quality observational studies | |

| or | |

| Evidence obtained from at least one moderate quality diagnostic accuracy study in addition to low quality studies | |

| Level IV | Evidence obtained from multiple moderate or low quality relevant observational studies |

| or | |

| Evidence obtained from multiple relevant low quality diagnostic accuracy studies | |

| Level V | Opinion or consensus of large group of clinicians and/or scientists. |

Source: Manchikanti et al[82].

RESULTS

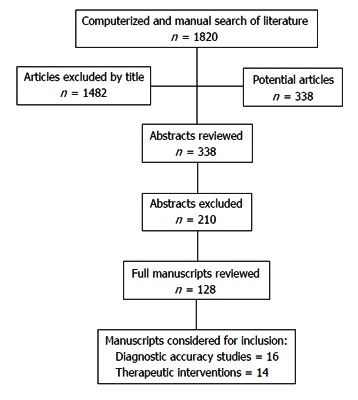

Figure 1 lists the study selection flow diagram of diagnostic accuracy studies and therapeutic intervention trials.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating literature evaluating diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic effectiveness of lumbar facet joint interventions.

Based on the search criteria, there were multiple diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy studies; however, utilizing inclusion criteria as described above, there were 16 diagnostic accuracy studies meeting inclusion criteria for methodological quality assessment[22-25,84-95], whereas there were 14 trials meeting inclusion criteria for therapeutic efficacy assessment[96-109]. Among the multiple trials not meeting methodological quality assessment inclusion criteria, Leclaire et al[110] was of significant importance. This trial was randomized and placebo controlled. It assessed 70 patients with a 12-wk follow-up. This was a relatively small study but more importantly, the technique used was inappropriate as was using intraarticular injections for diagnostic evaluation. Subsequently, the authors have agreed that the results may not be applied in clinical practice[111]. Multiple studies assessing the influence of factors of prevalence and accuracy of facet joint pain were also considered[112-123].

Methodological quality assessment

Methodological quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies is shown in Table 2 and methodological quality assessment of therapeutic interventions by Cochrane review criteria is shown in Table 3, whereas methodological quality assessment utilizing IPM-QRB criteria is shown in Table 4.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve block diagnostic studies

| Manchikanti et al[23] | Pang et al[25] | Schwarzer et al[22] | Schwarzer et al[84] | Manchikanti et al[86] | Manchikanti et al[79] | Manchikanti et al[85] | Manchikanti et al[93] | Manchikanti et al[94] | Manchikanti et al[88] | Manchikanti et al[82] | Manchikanti et al[90] | Manchukonda et al[91] | Manchikanti et al[92] | Manchikanti et al[95] | DePalma et al[24] | |

| (1) Was the test evaluated in a spectrum of subjects representative of patients who would normally receive the test in clinical practice? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (2) Was the test performed by examiners representative of those who would normally perform the test in practice? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (3) Were raters blinded to the reference standard for the target disorder being evaluated? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| (4) Were raters blinded to the findings of other raters during the study? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (5) Were raters blinded to their own prior outcomes of the test under evaluation? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| (6) Were raters blinded to clinical information that may have influenced the test outcome? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| (7) Were raters blinded to additional cues, not intended to form part of the diagnostic test procedure? | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (8) Was the order in which raters examined subjects varied? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (9) Were appropriate statistical measures of agreement used? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (10) Was the application and interpretation of the test appropriate? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (11) Was the time interval between measurements suitable in relation to the stability of the variable being measured? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (12) If there were dropouts from the study, was this less than 20% of the sample | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Total | 9/12 | 8/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 |

Y: Yes; N: No. Source: Lucas et al[80].

Table 3.

Methodological quality assessment of randomized trials of lumbar facet joint interventions utilizing Cochrane review criteria

| Manchikanti et al[102] | Carette et al[103] | Fuchs et al[104] | Nath et al[105] | van Wijk et al[97] | van Kleef et al[99] | Tekin et al[96] | Civelek et al[108] | Dobrogowski et al[98] | Cohen et al[109] | Ribeiro et al[107] | Moon et al[100] | Lakemeier et al[101] | Yun et al[106] | |

| Randomization adequate | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Concealed treatment allocation | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Patient blinded | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Care provider blinded | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | U | N | Y | N | N |

| Outcome assessor blinded | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | N | Y | N | N |

| Drop-out rate described | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| All randomized participants analyzed in the group | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Groups similar at baseline regarding most important prognostic indicators | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Co-intervention avoided or similar in all groups | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Compliance acceptable in all groups | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Time of outcome assessment in all groups similar | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| Score | 11/12 | 11/12 | 8/12 | 12/12 | 12/12 | 12/12 | 12/12 | 9/12 | 10/12 | 8/12 | 10/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 |

Y: Yes; N: No; U: Unclear. Source: Furlan et al[78].

Table 4.

Methodological quality assessment of randomized trials utilizing Interventional Pain Management techniques - Quality Appraisal of Reliability and Risk of Bias Assessment criteria

| Manchikanti et al[102] | Carette et al[103] | Fuchs et al[104] | Nath et al[105] | van Wijk et al[97] | van Kleef et al[99] | Tekin et al[96] | Civelek et al[108] | Dobrogowski et al[98] | Cohen et al[109] | Ribeiro et al[107] | Moon et al[100] | Lakemeier et al[101] | Yun et al[106] | |

| I Trial design and guidance reporting | ||||||||||||||

| (1) Consort or spirit | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| II Design factors | ||||||||||||||

| (2) Type and design of trial | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| (3) Setting/physician | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| (4) Imaging | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| (5) Sample size | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| (6) Statistical methodology | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| III Patient factors | ||||||||||||||

| (7) Inclusiveness of Population | ||||||||||||||

| For facet joint interventions: | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| (8) Duration of pain | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| (9) Previous treatments | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| (10) Duration of follow-up with appropriate interventions | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| IV Outcomes | ||||||||||||||

| (11) Outcomes assessment criteria for significant improvement | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| (12) Analysis of all randomized participants in the groups | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| (13) Description of drop out rate | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| (14) Similarity of groups at baseline for important prognostic indicators | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| (15) Role of co-interventions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| V Randomization | ||||||||||||||

| (16) Method of Randomization | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VI Allocation concealment | ||||||||||||||

| (17) Concealed treatment allocation | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| VII Blinding | ||||||||||||||

| (18) Patient blinding | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| (19) Care provider blinding | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| (20) Outcome assessor blinding | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| VIII Conflicts of interest | ||||||||||||||

| (21) Funding and sponsorship | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| (22) Conflicts of interest | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 45 | 40 | 26 | 42 | 36 | 40 | 37 | 28 | 29 | 28 | 32 | 32 | 38 | 37 |

Source: Manchikanti et al[79].

Study characteristics

Diagnostic accuracy study characteristics are shown in Table 5, and therapeutic efficacy trial characteristics are shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

Characteristics of studies assessing the accuracy of diagnostic facet joint injections and nerve blocks in the lumbar spine

| Study/methods | Participants | Intervention(s) | Outcome measures | Comments |

Results |

|

| Methodological quality scoring | Prevalence with 95%CI and criterion standard | False-positive rate with 95%CI | ||||

| Pang et al[25], 1998 | 100 consecutive adult patients with chronic low back pain with undetermined etiology were evaluated with spinal mapping | Single block was performed by injecting 2% lidocaine into facet joints | Verbal analog scale | This is the first study evaluating application of diagnostic blocks in the diagnosis of intractable low back pain of undetermined etiology with facet joint disease in potentially 48% of patients with a single block | Single block 90% pain relief | NA |

| Prospective, single block | Pain mapping | Only facet joint pain = 24% | ||||

| 8/12 | 90% pain relief | Lumbar nerve root and facet disease = 24% | ||||

| Total = 48% | ||||||

| Schwarzer et al[22], 1994 | 176 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain after some type of injury | Zygapophysial joint nerve blocks or intraarticular injections were performed with either 2% lignocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine | At least 50% pain relief concordant with the duration of local anesthetic injected | First study of evaluation of controlled prevalence and false-positive rates | 50% pain relief | 38% (95%CI: 30%-46%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 15% (95%CI: 10%-20%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Schwarzer et al[84], 1995 | 63 patients with low back pain lasting for longer than 3 mo underwent computed tomography and blocks of the zygapophysial joints | Patients underwent a placebo injection followed by intraarticular zygapophysial joint injections with 1.5 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine | At least 50% reduction in pain maintained for minimum of 3 h | This study shows that computed tomography has no place in the diagnosis of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain, with an impure placebo design | 50% pain relief | NA |

| Randomized, impure placebo, controlled diagnostic blocks | 40% (95%CI: 27%-53%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti [95], 2010 | 491 patients with chronic low back pain undergoing evaluation for facet joint pain with 80% pain relief and 181 patients with 50% pain relief | Controlled diagnostic blocks of lumbar facet joint nerves with 1% preservative-free lidocaine and 0.25% preservative-free bupivacaine 1 mL | At least 80% pain relief with the ability to perform previously painful movements | Higher prevalence than with 50% pain relief, but still higher than double block algorithmic approach | 50% pain relief | 50% pain relief |

| Retrospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 61% (95%CI: 53%-81%) | 17% (95%CI: 10%-24%) | ||||

| 9/12 | 80% pain relief | 80% pain relief | ||||

| 31% (95%CI: 26%-35%) | 42% (95%CI: 35%-50%) | |||||

| Manchikanti et al[85], 2000 | 200 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain were evaluated | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine were injected over facet joint nerves with 0.4 to 0.6 mL | 75% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | The study showed that the clinical picture failed to diagnose facet joint pain | 75% pain relief | 37% (95%CI: 32%-42%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 42% (95%CI: 35%-42%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| DePalma et al[24], 2011 | A total of 156 patients with chronic low back pain were assessed for the source of chronic low back pain including discogenic pain, facet joint pain, and sacroiliac joint pain | Dual controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine for the first block with 0.5% bupivacaine for the second | Concordant relief with 2 h for lidocaine and 8 h for bupivacaine with 75% pain relief as the criterion standard | This is the third study evaluating various structures implicated in the cause of low back pain with controlled diagnostic blocks[23,25] | 75% pain relief | NA |

| Retrospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 31% (24%-38%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[93], 2001 | Prevalence study in 100 patients with 50 patients below age of 65 and 50 patients aged 65 or over was assessed | Controlled diagnostic blocks | 75% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements was utilized as the criterion standard | This study showed higher prevalence of facet joint pain in the elderly compared to the younger age group in contrast to the latest study by Manchikanti et al[117] which showed no differences | 75% pain relief | < 65 yr = 26% (95%CI: 11%-40%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | < 65 yr = 30% (95%CI: 17%-43%) | > 65 yr = 33% (95%CI: 14%-35%) | ||||

| > 65 yr = 52% (95%CI: 38%-66%) | ||||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[94], 2001 | 100 patients with low back pain were evaluated. Patients were divided into 2 groups, group I was normal weight and group II was obese | Facet joints were investigated with diagnostic blocks using lidocaine 1% initially followed by bupivacaine 0.25%, at least 2 wk apart | A definite response was defined as relief of at least 75% in the symptomatic area | This study showed no significant difference between obese and non-obese individuals either with prevalence or false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks in chronic facet joint pain | 75% pain relief | Non-obese individuals = 44% (95%CI: 26%-61%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | ||||||

| 9/12 | Prevalence: | Obese individuals = 33% (95%CI: 16%-51%) | ||||

| Non-obese individuals = 36% (95%CI: 22%-50%) | ||||||

| Obese individuals = 40% (95%CI: 26%-54%) | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[23], 2001 | 120 patients were evaluated with chief complaint of chronic low back pain to evaluate relative contributions of various structures in chronic low back pain. All 120 patients underwent facet joint nerve blocks | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | This study evaluated all the patients with low back pain, even with suspected discogenic pain | 80% pain relief | 47% (95%CI: 35%-59%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 40% (95%CI: 31%-49%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[86], 1999 | 120 patients with chronic low back pain after failure of conservative management were evaluated | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | Concordant pain relief with 75% or greater criterion standard with ability to perform previously painful movements | This was the first study performed in the United States in the heterogenous population as previous studies were performed in only post-injury patients | 75% pain relief | 41% (95%CI: 29%-53%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 45% (95%CI: 36%-54%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[79], 2014 | 180 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain were evaluated after having failed conservative management | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine with or without Sarapin and/or steroids | 75% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | This study showed no significant difference if the steroids were used or not | 75% pain relief | 25% (95%CI: 21%-39%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 36% (95%CI: 29%-43%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[88], 2003 | At total of 300 patients with chronic low back pain were evaluated to assess the difference based on involvement of single or multiple spinal regions | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | This study shows a higher prevalence when multiple regions are involved | 80% pain relief | Single region: |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | Single region: | 17% (95%CI: 10%-24%) | ||||

| 21% (95%CI: 14%-27%) | Multiple regions: | |||||

| 9/12 | Multiple regions: | 27% (95%CI: 18%-36%) | ||||

| 41% (95%CI: 33%-49%) | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[82], 2014 | 120 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain and neck pain were evaluated to assess involvement of facet joints as causative factors | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | The results are similar to involvement of multiple regions with a prevalence of 40% as illustrated in another study | 80% pain relief | 30% (95%CI: 20%-40%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 40% (95%CI: 31%-49%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[90], 2004 | 500 consecutive patients with chronic, non-specific spinal pain were evaluated of which 397 patients suffered with chronic low back pain | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | Largest study performed involving all regions of the spine | 80% pain relief | 27% (95%CI: 22%-32%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 31% (95%CI: 27%-36%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchukonda et al[91], 2007 | 500 consecutive patients with chronic spinal pain were evaluated of which 303 patients were evaluated for chronic low back pain | Controlled diagnostic blocks with 1% lidocaine followed by 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% pain relief with ability to perform previously painful movements | Second largest study performed involving all regions of the spine | 80% pain relief | 45% (95%CI: 36%-53%) |

| Retrospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 27% (95%CI: 22%-33%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

| Manchikanti et al[92], 2007 | A total of 117 consecutive patients with chronic non-specific low back pain were evaluated, after lumbar surgical interventions, with postsurgery syndrome and continued axial low back pain | Controlled, comparative, local anesthetic blocks with 1% lidocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine | 80% relief as the criterion standard with ability to perform previously painful movements | Lower prevalence in postsurgery patients | 80% pain relief | 49% (95%CI: 39%-59%) |

| Prospective, controlled diagnostic blocks | 16% (95%CI: 9%-23%) | |||||

| 9/12 | ||||||

NA: Not applicable.

Table 6.

Study characteristics of randomized controlled trials of lumbar radiofrequency neurotomy, facet joint nerve blocks, and intraarticular injections

| Study/study characteristic/methodological quality Scoring | No. of patients and selection criteria | Control | Interventions | Outcome measures | Time of measurement | Reported results | Strengths | Weaknesses | Conclusion/comments |

| Radiofrequency neurotomy | |||||||||

| Civelek et al[108], 2012 | 100 patients with chronic low back pain with failed conservative therapy and strict selection criteria; however, without diagnostic blocks | Facet joint nerve block with local anesthetic and steroids in 50 patients | Conventional radiofrequency neurotomy at 80 °C for 120 s in combination with high dose local anesthetic and steroids, in 50 patients | Visual Numeric Pain Scale, North American Spine Society patient satisfaction questionnaire, Euro-Qol in 5 dimensions and ≥ 50% relief | 1, 6 and 12 mo | At one year, 90% of patients in the radiofrequency group and 69% of the patients in the facet joint nerve block group showed significant improvement compared to 92% and 75% at 6-mo follow-up | Randomized relatively large number of patients with 50 in each group | No diagnostic blocks were performed. High dose steroids and local anesthetics were utilized in both groups | Efficacy was shown even without diagnostic blocks, both for facet joint nerve blocks and radiofrequency neurotomy |

| Randomized, active-control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 28/48 | |||||||||

| Cohen et al[109], 2010 | 151 chronic low back pain, 51 patients with no diagnostic block, 50 patients a single diagnostic block, 50 patients in double diagnostic block | Radiofrequency neurotomy in patients without diagnostic blocks | Conventional radiofrequency neurotomy at 80 °C for 90 s in all patients; however, in 2 groups with either a single block paradigm or a double block paradigm testing for positive results | Greater than 50% pain relief coupled with a positive global perceived effect persisting for 3 mo | 3 mo | Denervation success rates in groups 0, 1 and 2 were 33%, 39% and 64%, respectively | Multicenter, randomized controlled trial with or without diagnostic blocks | Authors misinterpreted cost-effectiveness without consideration of many factors reported | Results showed efficacy when double diagnostic blocks were utilized |

| Randomized, double-blind, control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 8/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 28/48 | |||||||||

| Nath et al[105], 2008 | 40 patients with chronic low back pain for at least 2 yr with 80% relief of low back pain after controlled medial branch blocks. The patients were randomized into an active and a control group | Controlled sham lesion in 20 patients in the control group | The 20 patients in the active group received conventional lumbar facet joint radiofrequency neurolysis at 85 °C for 60 s. The 20 patients in the control group received sham treatment without radiofrequency neurolysis of the lumbar facet joints | Numeric Rating Scale, global functional improvement, reduced opioid intake, employment status | 6 mo | Significant reduction not only in back and leg pain; functional improvement; opioid reduction; and employment status in the active group compared to the control group | Randomized, double-blind trial after the diagnosis of facet joint pain with triple diagnostic blocks | Short-term follow-up with small number of patients | Efficacy of radiofreqency neurotomy was shown compared to local anesthetic injection and sham lesioning |

| Randomized, double-blind, sham control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 12/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 42/48 | |||||||||

| Tekin et al[96], 2007 | 60 patients with chronic low back pain randomized into 3 groups with 20 patients in each group. Single diagnostic block of facet joint nerves with 0.3 mL of lidocaine 2% with 50% or greater relief | Sham control with local anesthetic injection | Either pulsed radiofrequency (42 °C for 4 min) or conventional radiofrequency neurotomy (80 °C for 90 s) in 20 patients in each group | Visual analog scale and Oswestry Disability Index | 3, 6 and 12 mo | Visual analog scale and Oswestry Disability Index scores decreased in all groups from 3 procedural levels. Decrease in pain scores was maintained in the conventional radiofrequency group at 6 mo and one year. However, in pulsed radiofrequency group, the improvement was significant only at 6 mo, but not 1 yr | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing control, pulsed radiofrequency, and conventional radiofreqency neurotomy. Authors also utilized a parallel needle placement approach | Small sample size with a single block and 50% relief as inclusion criteria. Authors have not described the significant improvement percentages | Efficacy with conventional radiofreqency neurotomy up to one year, whereas efficacy with local anesthetic block with sham control radiofrequency neurotomy and pulsed radiofrequency neurotomy at 6 mo only |

| Randomized, active and sham, double-blind controlled trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 12/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 37/48 | |||||||||

| van Wijk et al[97], 2005 | 81 patients with chronic low back pain were evaluated with radiofreqency neurotomy with 41 patients in the control group with at least 50% relief for 30 min with a single block with intraarticular injection of 0.5 mL lidocaine 2% | Sham lesion procedure after local anesthetic injection | 40 patients received conventional radiofrequency lesioning at 80 °C for 60 s and 41 patients received sham lesioning | Pain relief, physical activities, analgesic intake, global perceived effect, short-form-36, quality of life measures | 3 mo | Global perceived effect improved after radiofrequency facet joint denervation. The visual analog scale in both groups improved. The combined outcome measures showed no difference between radiofreqency facet joint denervation (27.5% vs 29.3% success rate) | Double-blind, sham control, randomized trial | Poor selection with a single diagnostic block of 50% pain reduction even though 17.5% of the patients tested positive. Further, authors described that the needle was positioned parallel; however, the radiographic figures illustrate the needle was being positioned perpendicularly rather than parallel to the nerve | Lack of efficacy with methodological deficiencies and a short-term follow-up |

| Randomized, double-blind, sham control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 12/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 36/48 | |||||||||

| Dobrogowski et al[98], 2005 | 45 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain judged to be positive with controlled diagnostic blocks | Injection of saline in patients after conventional radiofrequency (85 °C for 60 s) neurotomy to evaluate postoperative pain | Conventional radiofrequency neurotomy at 85 °C for 60 s, followed by injection of either methylprednisolone or pentoxifylline | Visual analog scale, minimum of 50% reduction of pain intensity, patient satisfaction score | 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo | Greater than 50% of reduction of pain intensity was observed in 66% of the patients 12 mo later. There was no difference in the long-term outcomes | Randomized, active control trial | Very small study evaluating effectiveness of radiofrequency neurotomy and postoperative pain | Radiofrequency neurotomy effective with or without steroid injection after neurolysis |

| Randomized, active control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 10/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 29/48 | |||||||||

| van Kleef et al[99], 1999 | 31 patients with a history of at least one year of chronic low back pain randomly assigned to one of 2 treatment groups. Single diagnostic block with 50% relief | Sham control of radiofrequency after local anesthetic injection in 16 patients | The 15 patients in the conventional radiofrequency treatment group received an 80 °C radiofrequency lesion for 60 s | Visual analog scale, pain scores, global perceived effect, Oswestry Disability Index | 3, 6 and 12 mo | After 3, 6 and 12 mo, the number of successes in the lesion and sham groups was 9 of 15 (60%) and 4 of 16 (25%), 7 of 15 (47%) and 3 of 16 (19%), and 7 of 15 (47%) and 2 of 16 (13%) respectively. There was a statistically significant difference | Double-blind, randomized, sham controlled trial | A single block with a small sample with inclusion criteria of 50% pain relief to enter the study. The study has been criticized that electrodes were placed at an angle to the target nerve, instead of parallel (51A) | Efficacy shown in a small sample with a single diagnostic block |

| Randomized, double-blind, sham control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 12/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 40/48 | |||||||||

| Moon et al[100], 2013 | 82 patients were included with low back pain with 41 patients in each group either with a parallel placement of the needle or perpendicular placement of the needle | An active control trial with needle placement with perpendicular approach | 41 patients in each group were treated with radiofrequency (80 °C for 90 s) after appropriate diagnosis of facet joint pain with dual diagnostic blocks with 50% relief as the criterion standard. The needle was positioned either utilizing a discal approach or perpendicular or utilizing tunnel vision approach with parallel placement of the needle | NRS, ODI | 1 and 6 mo | Patients in both groups showed a statistically significant reduction in NRS and Oswestry disability index scores from baseline to that of the scores at 1 and 6 mo (all P < 0.0001, Bonferroni corrected) | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. The major strength is that authors have proven that parallel approach may not be the best as has been described. Diagnosis of facet joint pain by dual blocks | Active controlled trial without placebo group. Short-term follow-up | Positive results in an active controlled trial, in a relatively short-term follow-up of 6 mo, with positioning of the needle either with distal approach (perpendicular placement or tunnel vision) with parallel placement of the needle with some superiority with perpendicular approach. This trial abates any criticism of needle positioning one way or the other and the traditional needle positioning appears to be superior to parallel needle placement |

| Prospective, randomized, comparative study | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 38/48 | |||||||||

| Lakemeier et al[101], 2013 | 56 patients were randomized into 2 groups with 29 patients receiving intraarticular steroid injections and 27 patients receiving radiofrequency denervation after the diagnosis was made with intraarticular injection of local anesthetic with a single block | Intraarticular injection of local anesthetic and steroid | Radiofrequency neurotomy for 90 s at 80 °C | Roland-Morris questionnaire, VAS, ODI, analgesic intake | 6 mo | Pain relief and functional improvement were observed in both groups. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for pain relief and functional status improvement | Lack of placebo group. Relatively short-term follow-up | Randomized, double-blind trial with single diagnostic block with intraarticular injection | Both groups showed improvement. Effectiveness at 6 mo in both groups with intraarticular injection or radiofrequency neurotomy |

| Randomized, double-blind, active controlled trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 37/48 | |||||||||

| Lumbar facet joint nerve blocks | |||||||||

| Civelek et al[108], 2012 | 100 patients with chronic low back with failed conservative therapy and strict selection criteria; however, without diagnostic blocks | Blocks of facet joint nerves with local anesthetic and steroids | Conventional radiofrequency neurotomy at 80 °C for 120 s in combination with high dose local anesthetic and steroids | Visual Numeric Pain Scale, North American Spine Society patient satisfaction questionnaire, Euro-Qol in 5 dimensions and ≥ 50% relief | 1, 6 and 12 mo | At the end of one year, 90% of patients in the radiofrequency group and 69% of the patients in the facet joint nerve block group showed significant improvement vs 92% and 75% at 6-mo follow-up | Randomized active-control trial with relatively large number of patients with 50 in each group | No diagnostic blocks were performed. High dose steroids and local anesthetics were provided in both groups | Results showed efficacy even without diagnostic blocks, both for facet joint nerve blocks and radiofrequency neurotomy |

| Randomized, active-control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 28/48 | |||||||||

| Manchikanti et al[102], 2010 | 120 patients with chronic low back pain of facet joint origin treated with therapeutic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks Double diagnostic blocks with 80% relief | Local anesthetic only | Total of 120 patients with 60 patients in each group with local anesthetic alone or local anesthetic and steroids. Both groups were also divided into 2 categories each with the addition of Sarapin | Numeric Rating Scale, Oswestry Disability Index, employment status, and opioid intake | 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 mo | Significant pain relief was shown in 85% in local anesthetic group and 90% in local anesthetic with steroids group at the end of the 2 yr study period in both groups, with an average of 5-6 total treatments | Randomized trial with relatively large proportion of patients with 2-yr follow-up, with inclusion of patients diagnosed with controlled diagnostic blocks | Lack of placebo group | Effectiveness demonstrated with facet joint nerve blocks with local anesthetic with or without steroids |

| Randomized, double blind, active control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 11/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 45/48 | |||||||||

| Lumbar intraarticular injections | |||||||||

| Carette et al[103], 1991 | Patients with chronic low back pain who reported immediate relief of their pain after injection of local anesthetic into the facet joints. Single diagnostic blocks with 50% relief were randomly assigned to receive injections under fluoroscopic guidance | Intraarticular injection of isotonic saline | Injection of either sodium chloride or methylprednisolone into the facet joints (49 for isotonic saline and 48 for sodium chloride). Only one injection was provided | Visual Analog Scale, McGill Pain Questionnaire, mean sickness impact profile | 1, 3 and 6 mo | After 1 mo, 42% of the patients in the methylprednisolone group and 33% in the sodium chloride group reported marked or very marked improvement. At the 6 mo evaluation, 46% in the methylprednisolone group and 15% in the placebo group showed sustained relief. Revised statistics showed 22% improvement in active group and 10% in control group | Well-performed randomized, double-blind controlled trial | Only single block was applied and patients were treated with steroids without local anesthetic with only one treatment and expected 6 mo of relief | The authors concluded that results were negative in an active-control trial with injection of either sodium chloride solution or steroid into the facet joints after diagnosis with a single block |

| Randomized, double blind, impure placebo or active- control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 11/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 40/48 | |||||||||

| Fuchs et al[104], 2005 | 60 patients with chronic low back pain were included with patients randomly assigned into 2 groups. No diagnostic blocks | Active-control study with no control group | Intraarticular injection of hyaluronic acid vs glucocorticoid injection | VAS, Rowland-Morris Questionnaire, ODI, low back outcomes score, short form-36 | 3 and 6 mo | Patients reported lasting pain relief, better function, and improved quality of life with both treatments | Randomized, active-control, double-blind study | Relatively small sample of patients with 6 mo follow-up without a placebo group, without diagnostic blocks | Undetermined (clinically inapplicable) results with high number of injections during a 6-mo period |

| Randomized, double-blind, active-control trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 8/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 26/48 | |||||||||

| Ribeiro et al[107], 2013 | 60 patients with a diagnosis of facet joint syndrome randomized into experimental and control groups | Triamcinolone acetonide intramuscular injection of 6 lumbar paravertebral points | Intraarticular injection of 6 lumbar facet joints with triamcinolone hexacetonide | Pain visual analogue scale, pain visual analogue scale during extension of the spine, Likert scale, improvement percentage scale, Roland-Morris, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, and accountability of medications taken | 1, 4, 12 and 24 wk | Both groups showed improvement with no statistical difference between the groups. Improvement "percentage" analysis at each time point showed significant differences between the groups at week 7 and week 12. Improvement percentage was > 50% at all times in the experimental group with intraarticular steroids; however, significant difference was noted at 24 wk | Randomized, double-blind controlled trial | Diagnostic blocks were not employed, thus, many patients without facet joint pain may have been included in this trial | Overall intraarticular steroids showed positive effectiveness for 24 wk compared to intramuscular steroids provided in a double-blind manner |

| Randomized, double-blind, active control | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 10/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 32/48 | |||||||||

| Lakemeier et al[101], 2013 | 56 patients were randomized into 2 groups receiving intraarticular steroid injections or radiofrequency denervation after the diagnosis was made with intraarticular injection of local anesthetic with a single block | Intraarticular injection of local anesthetic and steroid in 29 patients | Radiofrequency neurotomy for 90 s at 80 °C in 27 patients | Roland-Morris questionnaire, VAS, ODI, analgesic intake | 6 mo | Pain relief and functional improvement were observed in both groups. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for pain relief and functional status improvement | Lack of placebo group. Relatively short-term follow-up | Randomized, double-blind trial with single diagnostic block with intraarticular injection | Both groups showed improvement. Effectiveness of both modalities at 6 mo in both groups |

| Randomized, double-blind, active controlled trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 37/48 | |||||||||

| Yun et al[106], 2012 | 57 patients with facet syndrome were assigned to 2 groups with 32 patients in the fluoroscopy group and 25 patients in the under ultrasonography group without diagnostic blocks | Intraarticular injection of lidocaine and triamcinolone under fluoroscopic guidance | Intraarticular injection of lidocaine and triamcinolone under ultrasonic guidance | VAS, physician’s and patient’s global assessment (PhyGA, PaGA), modified ODI | 1 wk, 1 and 3 mo | Each group showed significant improvement from the facet joint injections. However at a week, a mo, and 3 mo after injections, no significant differences were observed between the groups | Randomized trial | Short-term follow-up with no diagnostic blocks, thus increasing the potential for inclusion of patients without facet joint pain. The aim of study mainly was to confirm if ultrasonic imaging was appropriate | The study showed positive results in both groups with intraarticular steroid injections with a short-term follow-up whether performed under ultrasonic guidance or fluoroscopy |

| Randomized, active controlled trial | |||||||||

| Quality scores: | |||||||||

| Cochrane = 9/12 | |||||||||

| IPM-QRB = 26/48 | |||||||||

IPM-QRB: Interventional Pain Management Techniques - Quality Appraisal of Reliability and Risk of Bias Assessment; VAS: Visual analog scale; ODI: Oswestry Disability Index.

Among the diagnostic accuracy studies, 6 studies were performed utilizing ≥ 75% pain relief as the criterion standard[24,85-87,93,94]. All told there were 856 patients, a heterogenous population with prevalence ranging from 30% to 45%, including a false-positive rate of 25% to 44%. These results are also similar to 80% pain relief as the criterion standard studied in 5 studies[23,89-91,95] in 1431 patients. The prevalence in a heterogenous population ranged between 27% and 41%. However, utilizing controlled diagnostic blocks, the prevalence was shown somewhat differently in specific populations with 30% in patients younger than 65 years and 52% in patients older than 65[93], 36% in non-obese patients and 40% in obese patients[94], 16% in post surgery patients[92], and 21% with involvement of a single region[88].

Among the therapeutic interventions, a total of 14 trials met inclusion criteria with 9 trials evaluating lumbar radiofrequency neurotomy[96-101,105,108,109], 2 trials evaluating lumbar facet joint nerve blocks[102,108], and 5 trials evaluating the role of intraarticular facet joint injections[101,103,104,106,107]. Among the radiofrequency neurotomy trials, of the 9 trials included, 7 moderate to high quality trials showed long-term effectiveness[96,98-101,105,108], whereas one moderate to high quality trial showed a lack of effectiveness[97] with one trial showing short-term effectiveness[109]. Among the long-term trials with effectiveness assessed at least for one year, Civelek et al[108] included 50 patients, Tekin et al[96] included 20 patients in the conventional radiofrequency neurotomy groups, and van Kleef et al[99] included only 15 patients in the radiofrequency neurotomy group showing positive results with a total number of 85 patients included among the 3 trials. van Wijk et al[97], showing a lack of effectiveness, included 40 patients undergoing radiofrequency neurotomy. Among the other studies, Cohen et al[109] included 14 patients with controlled diagnostic blocks, Nath et al[105] included 20 patients with triple diagnostic blocks, Dobrogowski et al[98] included 45 patients with controlled diagnostic blocks, Moon et al[100] included 82 patients utilizing 2 different types of techniques with controlled diagnostic blocks, and Lakemeier et al[101] included 27 patients with an intraarticular injection of local anesthetic with a single block.

The evidence for therapeutic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks was assessed in 2 RCTs[102,108]. In these trials, Manchikanti et al[102] studied 120 patients with chronic lumbar facet joint pain with a confirmed diagnosis with a criterion standard of 80% pain relief using controlled diagnostic blocks after failure of conservative management. At the end of a 2-year study period, significant pain relief was seen in 85% of the patients who received a local anesthetic and 90% of the patients who received a local anesthetic with steroids. The patients received an average of 5 to 6 total treatments. In the second study, Civelek et al[108] assessed 100 patients suffering from chronic low back pain. These patients had failed conservative therapy utilizing noninvasive diagnostic criteria; however, without diagnostic blocks. They compared lumbar facet joint nerve blocks with conventional radiofrequency neurotomy. Effectiveness was seen in 69% of the patients who received facet joint nerve blocks. In the radiofrequency neurotomy group, 90% effectiveness was seen. Civelek et al[108] showed significant improvement in 90% of the patients at one year follow-up, Cohen et al[109] showed 64% of the patients responding at 3 mo selected with controlled diagnostic blocks, Nath et al[105] showed at 6 mo follow-up significant reduction in the majority of patients, Tekin et al[96] reported a significant percentage of patients with appropriate relief at one year in the conventional radiofrequency neurotomy group, van Wijk et al[97] showed a lack of response at 3 mo follow-up, Dobrogowski et al[98] showed effectiveness of radiofrequency neurotomy in 66% of the patients at one year follow-up, van Kleef et al[99] showed effectiveness of radiofrequency neurotomy at one year in 47% of the patients, Moon et al[100] showed significant reduction in pain and disability index scores at the end of one year, and finally Lakemeier et al[101] showed significant improvement with conventional radiofrequency neurotomy at the end of 6 mo.

Intraarticular injections were studied in 5 trials[101,103,104,106,107]. Of these, 3 high quality RCTs showed effectiveness with short-term follow-up of less than 6 mo[101,106,107]. However, 2 moderate to high quality RCTs showed opposing results with a lack of effectiveness[103,104]. Ribeiro et al[107] showed effectiveness of intraarticular injections at the end of 6 mo with selection criteria not including diagnostic blocks. Lakemeier et al[101] showed significant improvement with selection of patients with a single intraarticular injection at 6 mo. Yun et al[106] showed positive results at the end of 3 mo with selection of patients without diagnostic blocks. In contrast, Carette et al[103] in a large controlled trial showed a lack of effectiveness of intraarticular steroid injections with selection of the patients with a single block and Fuchs et al[104] provided undetermined results with a large number of injections over a period of 6 mo which is not applicable clinically.

Analysis of evidence

Lumbar facet joint nerve blocks in the diagnosis of chronic lumbar facet joint pain have an evidence level of I based on 7 controlled diagnostic studies with 80% or more pain relief[23,88-92,95] and 6 studies with a criterion standard of at least 75% pain relief[24,85-87,93,94].

For therapeutic interventions, there is level II evidence for the long-term effectiveness of using lumbar facet joint nerve blocks and radiofrequency neurotomy. For short-term improvement of 6 mo or less, lumbosacral intraarticular injections have evidence that is level III.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review assessing the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy of lumbar facet joint interventions assessed diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks and therapeutic intraarticular injections, facet joint nerve blocks, and radiofrequency neurotomy. There is level I evidence for the diagnostic accuracy of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks, and level II evidence for radiofrequency neurotomy, level II evidence for lumbar facet joint nerve blocks, and level III evidence for lumbosacral intraarticular injections for long-term improvement of > 6 mo.

Level I evidence is established for diagnostic accuracy studies based on multiple high quality diagnostic accuracy studies that have pain relief of at least 75% as the criterion standard utilizing dual blocks with mild variability in the prevalence and false-positive rates. The therapeutic efficacy of radiofrequency neurotomy, based on multiple moderate to high quality randomized trials is level II with 7 trials[96,98-101,105,108] showing efficacy for at least 6 mo follow-up, with discordant evidence demonstrating a lack of effectiveness in one moderate to high quality RCT[97]. There is level II evidence for lumbar facet joint nerve blocks based on 2 moderate to high quality RCTs[102,108] for long-term improvement. For lumbosacral intraarticular injections, the evidence is level III based on 3 RCTs[101,106,107] showing effectiveness with 2 randomized trials showing a lack of effectiveness[103,104].

In recent years, understanding lumbar facet joint pain, not only with pathophysiology, but with diagnostic and treatment strategies, has expanded with numerous publications[10,15,22-25,34-49,53-55,84-123]. Hancock et al[53] systematically assessed tests to identify the structures in the low back responsible for chronic pain, including facet joints. Their results demonstrated the lack of diagnostic accuracy for various tests. Thus, controlled diagnostic blocks seem to be the only viable and appropriate diagnostic method, despite discussions about the precision and accuracy of these techniques[10,34]. Although the majority of systematic reviews demonstrate the accuracy of controlled diagnostic blocks when performed by interventional pain physicians[10,28,34], others failed to demonstrate accuracy[50-52] though debate continues[10,28,34].

Rubinstein et al[32] of the Cochrane Review Musculoskeletal Group conducted a best-evidence review of neck and low back pain diagnostic procedures. They concluded that surprisingly, many of the orthopedic tests for the low back had very little evidence to support their diagnostic accuracy in clinical practice. They also concluded that lumbar facet joint nerve blocks performed for diagnostic purposes had moderate evidence for their use. This was based on systematic reviews and diagnostic accuracy studies performed by interventional pain physicians prior to 2008. Since then, the literature has expanded considerably. As such, despite the fact that a true placebo control technique may be the gold standard, due to practical difficulties, such as limited clinical utility and cost implications, as well as the ethical and logistic issues associated with using a true placebo[124-126], controlled comparative local anesthetic blocks with local anesthetics, both short-acting and long-acting, have become a recognized way for diagnosing chronic lumbar facet joint pain, without disc herniation or radicular pain, after failing conservative management. Once the diagnosis is established, patients may be offered treatment with lumbar facet joint nerve blocks or radiofrequency neurotomy, and perhaps intraarticular facet injections.

Significant progress also has been made with therapeutic interventions, according to RCTs and systematic reviews published over the past 5 years. Consequently, the quality and level of evidence for therapeutic interventions has been improving, with level II evidence for long-term relief (longer than 6 mo) for radiofrequency neurotomy and therapeutic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks, even though the evidence for lumbosacral intraarticular injections continues to lack for long-term improvement and is level III for short-term improvement.

There has been substantial controversy in reference to technique. Bogduk et al[71] have recommended parallel placement of the needle to achieve appropriate results with conventional radiofrequency neurotomy. However, an analysis of results shows no significant difference in outcomes with placement of the needle, either parallel or perpendicular. In fact, Moon et al[100], in a prospective randomized comparative trial of 82 patients, showed improvement to be equal in both groups. The selection criteria were dual diagnostic blocks with 50% relief. Dobrogowski et al[98] compared 45 consecutive patients in a randomized active-control trial studying the role of methylprednisolone or pentoxifylline after performing conventional radiofrequency neurotomy. The results were similar in both groups without any significant influence of methylprednisolone. The study essentially looked at postoperative pain relief with steroids after conventional radiofrequency neurotomy. Cohen et al[109] assessed the efficacy of radiofrequency neurotomy with a 3 mo follow-up with either no diagnostic blocks, single diagnostic block, or dual diagnostic blocks. The results were superior in patients selected after dual diagnostic blocks, with 64% responding; whereas in patients without a diagnostic block, the response rate was 33% and in the group with a single diagnostic block, the response rate was 39%. Civelek et al[108] performed conventional radiofrequency neurotomy in 50 patients without first performing any diagnostic blocks with significant improvement in 90% of patients at the end of one year. Nath et al[105], in a randomized double-blind sham control trial with a 6 mo follow-up, showed effectiveness of conventional radiofrequency neurotomy compared to sham lesioning and local anesthetic injection. The 2 RCTs assessing facet joint nerve blocks showed positive results in 69% of the patients by Civelek et al[108] and 90% of the patients by Manchikanti et al[102] with local anesthetic alone or with local anesthetic and steroids (85% in the local anesthetic group and 90% in the local anesthetic with steroids group) at the end of a 2-year period. However, lumbosacral intraarticular injections did not produce convincing positive results, with some benefit on a short-term basis in 3 cases[101,106,107] and 2 trials[103,104] showing no response.

Even now, there remains significant controversy regarding the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic efficacy of facet procedures, particularly in reference to interventional techniques, including escalating utilization patterns and costs[6,10,13,14,68,127]. In fact, in the United States, the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services conducted an assessment of the appropriateness of facet joint injections, concluding that many of the procedures were inappropriate, without medical necessity and indications[117]. Further, in the current regulatory atmosphere, many local coverage determinations may paradoxically increase the utilization of facet joint interventions[68]. The present data show that facet joint interventions have increased 293% per 100000 fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare population from 2000 to 2013, with an increase of 213% for lumbar facet joint interventions and a 522% for lumbosacral facet neurolysis. Likewise, there has been an increase in cervical and thoracic facet joint nerve blocks of 350%, and an increase in facet neurolysis of 845% from 2000 to 2013 in the FFS population[6,13,14,68]. However, the lumbar procedure increases appear to be smaller than cervical and thoracic facet joint interventions, even though the absolute procedure numbers are much higher for lumbar facet joint interventions. These data reflect only FFS Medicare patients in the United States, thus increases could be even higher.

There has been substantial discussion about various treatment strategies, control design of trials, placebo and nocebo effects, outcomes assessment between 2 active treatments rather than baseline to follow-up period, and ever-changing methodological quality assessment[10,15,50,51,55,128,129]. For interventional techniques, complex mechanisms and variations in placebo and nocebo responses have been well described[123-126,128-133]. Thus far, appropriately designed placebo studies, i.e., injecting inactive solutions into inactive structures, have shown substantially accurate results without significant placebo effect[134,135]. Further, it is crucial to note that most investigators are missing the role of the nocebo effect[123-126]. Thus, clinical trials must be designed appropriately with clinical relevance to avoid erroneous conclusions. Further, many studies have used subacute or acute patients without standard conservative management.

The results of this systematic review are similar to the results of numerous other systematic reviews[10,28,51,54,55,69-73]; however, they do not agree with the systematic reviews of others[15,50]. Systematic reviews that showed a lack of effectiveness were often based on flawed methodology, also utilized in RCTs[136-144]. Our results are similar to those of Falco et al[28,54] even though we used stricter criteria for the methodological quality assessment. In addition, in a systematic review of the comparative effectiveness of different solutions, including local anesthetics and steroids, Manchikanti et al[136] showed equal efficacy of local anesthetic compared to steroids in long-term follow-up of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks; lumbar intraarticular facet injections were not found to be effective.

This evaluation included only RCTs for efficacy assessment, thus it can be argued that we missed many high quality observational studies[71,144]. However, with adequate randomized trials available for radiofrequency neurotomy and intraarticular injections, inclusion of observational studies would not alter the findings.

The current study illustrates the diagnostic value and validity of nerve blocks and the therapeutic effectiveness of facet joint interventions, specifically radiofrequency neurotomy and facet joint nerve blocks for managing lumbar spine pain. Sixteen diagnostic accuracy studies and 14 RCTs of therapeutic interventions demonstrated level I evidence for using lumbar facet joint nerve blocks as a diagnostic tool for chronic low back pain, level II evidence for the therapeutic benefit of radiofrequency neurotomy and facet joint nerve blocks for long-term improvement (longer than 6 mo), and level III evidence with lumbosacral intraarticular injections for short-term improvement. Despite the debate regarding appropriate use of therapeutic modalities in managing lumbar facet joint pain, the accuracy of diagnostic facet joint nerve blocks and the efficacy of therapeutic facet joint interventions are supported by high-quality evidence for appropriately selected patients after failure of conservative treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Drs. Manchikanti, Hirsch, Falco, and Boswell contributed to this work. Drs. Manchikanti and Boswell designed the research; Drs. Manchikanti and Falco performed the research; Drs. Manchikanti and Hirsch contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Drs. Manchikanti and Hirsch analyzed the data; Drs. Manchikanti and Hirsch wrote the paper. All authors reviewed all contents and approved for submission.

COMMENTS

Background

In this systematic review, the diagnostic validity and therapeutic value of lumbar facet joint interventions in managing chronic low back pain were performed. Facet joint interventions are one of the multitude of modalities in managing chronic low back pain without disc herniation. There is a paucity of literature of not only systematic reviews, but also randomized controlled trials (RCTs) describing the efficacy of various modalities utilized and also diagnostic validity with controlled diagnostic blockade.

Research frontiers

There is a paucity of literature in assessing the diagnostic capability of various non-interventional and interventional modalities including radiologic investigations. Due to a lack of validity of various types of investigations, controlled diagnostic blocks have been considered as a reliable method in arriving at the diagnosis of facet joint pain. Similarly, there is also a paucity of literature in reference to therapeutic efficacy of various types of facet joint interventions utilized in managing chronic low back pain including intraarticular injections, facet joint nerve blocks, and radiofrequency neurotomy. By the same token, there is also a paucity of systematic reviews assessing the value and validity of diagnostic and therapeutic facet joint interventions in the lumbar spine.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The previous systematic reviews have limited their assessment to either diagnostic or therapeutic validity and value. Further, assessment has been carried utilizing variable methodologic quality assessments. In this systematic review, the authors have utilized the most recent methodologic quality assessment instruments to assess not only bias, but also the methodologic quality of the studies included. Further, this systematic review includes all the up-to-date RCTs which were not included in previous systematic reviews.

Applications

The results of this systematic review are clinically oriented and applicable in daily practices. However, facet joint interventions must be performed only after the failure of all conservative modalities of treatments.

Terminology

Facet joint pain is described variously across the globe as facet joint pain, facet joint syndrome, and zygapophysial joint pain. Similarly, the structures are also described as either facet joints or zygapophysial joints. The innervation is described as medial branches from lumbar 1 (L1) through L4, whereas L5 innervation is described as the dorsal ramus.

Peer-review

This article is concerning management of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. This thesis is an excellent review.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data sharing statement: There is no such statement required. This manuscript has not described any basic research or clinical research.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 11, 2015

First decision: September 30, 2015

Article in press: January 29, 2016

P- Reviewer: Chen C, Guerado E, Korovessis P, Tokuhashi Y S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, Birbeck G, Burstein R, Chou D, Dellavalle R, Danaei G, Ezzati M, Fahimi A, et al. S. Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, Williams G, Smith E, Vos T, Barendregt J, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:968–974. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driscoll T, Jacklyn G, Orchard J, Passmore E, Vos T, Freedman G, Lim S, Punnett L. The global burden of occupationally related low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:975–981. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, Jackman AM, Darter JD, Wallace AS, Castel LD, Kalsbeek WD, Carey TS. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:251–258. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, Benyamin RM, Hirsch JA. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation. 2014;17 Suppl 2:3–10. doi: 10.1111/ner.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJ, Hirsch JA. An updated assessment of utilization of interventional pain management techniques in the Medicare population: 2000 - 2013. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E115–E127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, Delamarter RB. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:67–76. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]