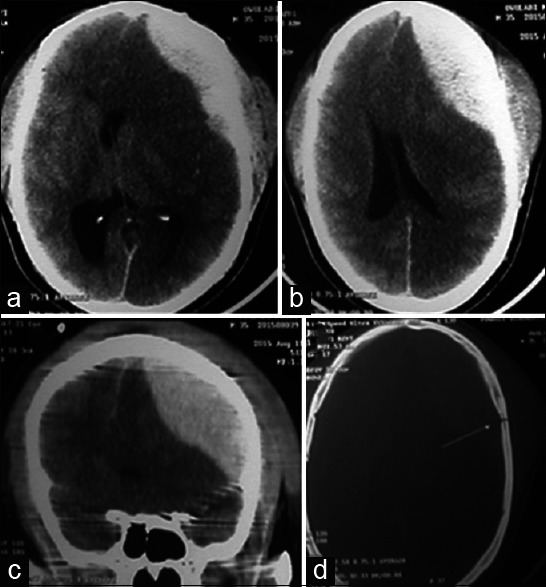

During the course of the peer review for a manuscript (a tale of two acute extradural hematomas [AEDH]) that we submitted to Surgical Neurology International, some of the reviewers expressed great outrage, actually righteous indignation, at what they considered suboptimal care given by us the managing team to the fatal one in the two cases reported. This has to do with the delay in procuring the required diagnostic brain computed tomography (CT) scan which when eventually done revealed an otherwise salvageable AEDH. The young victim had walked into and talked in the hospital at admission. He was GCS 14/15. The said reviewers’ outrage, by no means offensive to us, compelled us to do this editorial. It is an attempt to put things in their practical perspective, against the backdrop of the health system in place at that time.

The prevalent health indicators in most developing countries, otherwise known as low-middle income countries (LMICs), and certainly in Nigeria, are still far below the minimum levels recommended globally.[4,10] Hence, universal health coverage even for most basic human maladies is still something of a pipe dream in these impoverished regions of the world. The reasons for this dismal state are many but few salient ones include poor health infrastructures, extreme poverty among the population, inequality in access to health care, and dearth of qualified medical and paramedical personnel in the health systems.[3,4,10] Important as these factors are, however, our on-the-field experience practicing neurological surgery, even subspecialized neurosurgery, skull base surgery, in an LMIC makes one to say without any equivocation that the most significant impediment to a tolerably adequate health care is the health care financing model that obtains in most developing countries.[1] This model is the privately funded, out-of-pocket (OOP) settling of the bills for health care.[4,10,12] It is also known as a payment at the point of service (POS), model. It is what is prevalent in most sub-Sahara African countries, including Nigeria.[7,10,12] It is virtually a death-dealing solution for health system financing. It not only empties the pockets of the patients and their relations when most vulnerable, it is actually said to push some 250 million people yearly in the developing countries to extreme poverty.[7]

At present, although Nigeria is a major global crude-oil exporting nation of some 170 million people, most of her socioeconomic metrics are far from salutary.[11] The minimum wage is a paltry 18,000 Nigerian Naira (60 USD) and more than half the people live below 2 USD a day. The health care system is also only organized on paper. With a highly dysfunctional health care pyramid, partly due to lack of qualified personnel, especially in the rural areas where majority of the population resides, the few University Teaching Hospitals, located as a rule in the urban centers, are daily inundated with human maladies of sheer imponderable proportions. These range from the mild, mundane (cold and catarrh, or “flu”) to the severe-advanced stages of sundry systemic malignancies. On top of all these is a daily deluge of multisystem trauma, victims of the untrammeled carnage on the roads.

Thus, when a sick person, suffering from either a chronic illness or an acute/traumatic condition, comes from this poor hapless pool of people to the average Nigerian public hospital, he is likely to meet fairly self-well-motivated health care personnel (admittedly there are some few bad ones) whose salaries have been paid by the government subventions/grants. This is about the only significant contribution the government makes to the cost of his in-hospital health care: Payment of personnel salaries in the government hospitals. The patient or the relations however have to pay for every other aspect of their care including registration in the hospital records, laboratory/radiological investigations, ward admission costs, drugs, and in-hospital consumables including needles and syringes, and even swabs of cotton wool, and so on.[9,10] He must also bear all the costs of the surgical/anesthetic care, OOP, be it minor procedures like incision and drainage of skin abscesses, or obstetric cesarean section, or complicated/exorbitantly expensive neurosurgical procedures.[5,6,8,9,12] There are usually “indigents’ funds” set apart, more so in the University Teaching Hospitals, for the care of the extremely poor or for dire emergencies, but these are usually no more than few drops of water in the oceans of the compelling/competing demands. There are also some arrangements for payment deferments, whereby a sick person may be given all the in-hospital services desired, diagnostic and therapeutic, in lieu of payment later. But extreme poverty, making the eventual hospital bill too imponderable to bear to the victims, or just arrant mischief by those who are otherwise able but refuse to settle the hospital bills so incurred, also frustrate this measure many times.

However, the government-subsidized public general or University Teaching Hospitals are not the only players in the health care delivery. Indeed, they are not the major players in many developing countries.[10] There are private health facilities who also attend to the health needs of the people.[10] They are usually called private hospitals but most are not worth the name really. They are mere consulting clinics but they go as far as offering in-house medical and surgical inpatient services. Many lack the minimum basic tools for a college first-aid facility. This is especially so in the rural areas and the urban slums. Whatever they are, however, five-star health facilities or ramshackle structures ill-manned in the middle of nowhere, they are strictly for-profit ventures. They receive no government subvention whatever. If anything, they actually are required to pay significant administrative fees to the government. These fees, some of them unverifiable, are sometimes so exorbitant they actually raise the costs of doing these businesses, which cost would eventually be transferred to their clients.

Only very small proportion of such private health facilities dares to attempt treating anything neurosurgical. Even some of them that you would think appear well-furnished enough to try would rather refer a mild head injured, GCS 15, no neurological deficits, all other systems normal to the neurosurgeons in the academic centers. The result, many times, includes what have actually been considered needless referrals across hundreds of kilometers of dangerous national roads for the neurosurgical care of mild head injury in our practice.[2]

In the as-yet crisis-ridden health system of Nigeria, however, there are times when even this not-too-good pattern breaks down. At the most extreme of such bad times, the public University Teaching Hospitals are completely shut down for months (hospital wards actually gather dusts and cobwebs) by industrial conflicts and stalemates called by one or a group of the health workers’ unions. Some neurosurgical patients, even with severe head injury and complex brain tumors, would then end up in some of these private clinics, who would have no option but to take them in. These are usually a few of these health facilities that have some basic requirements for life-saving surgical treatments. It is needless to say however that only the upper middle class and above are the ones able to bear the cost of care in these private entities.

It is in one such facility that the drama told in the tale of two AEDHs took place in Ibadan, Nigeria. But the impression we are compelled to not let the reviewers get away with is that any of the health care workers, physicians, and all involved in that frontline battle experience failed to live up to their professional calling in any way. If anything, they actually put way, way beyond their calling into those cases. It is just that the socioeconomic limitations of the health care system of this typical developing country failed us in the first case, and only barely salvaged the second.

The outrage of some of the reviewers to that tale, as it pertains to the tragic loss of the first patient is therefore understandable. It is the same with us. Indeed, it is the reason we told this tragic (we never intended it a comic) tale. There was a total, some 3-month-or-so-long, breakdown of health care in the country's university public teaching hospitals, one of which we work in. This was due to a protracted strike action by some hospital workers’ union and it was a most disheartening situation.

There being nowhere else to go in that extreme situation, the patients ended up in this one private hospital, somewhat abler to offer the basic resuscitative care needed for such patients. The physicians there knew they had the benefit of the cover of an academic neurosurgeon (myself) in a nearby University Teaching Hospital, in the same metropolis. They had had the benefits of consulting with me in similar situations in the past. Moreover, we have together pulled off some highly gratifying miraculous feats saving near-death situations on some of those occasions. They quickly reviewed the traumatic brain injury cases in that tale; appropriately requested brain CT imaging for them, and waited for the relations to raise the funds to procure these tests.

Two salient points are necessary at this juncture. One, this hospital although a private, for-profit venture, actually was giving all the initial in-hospital care to the patients without yet demanding for payments, indeed waiving most of it. Two, CT scanner was not available in this hospital, could only be procured in another private imaging center in another part of the town. Even this imaging center opened shop only a couple of months earlier. It was the search by the patients’ relation for the funds to take to this other facility, the imaging center, for the brain CT that caused the fatal delay at issue in the first case of that tale. And even when the brain CT was eventually procured, the for-profit private hospital put so much of its resources down, no payment insisted on, to help facilitate the possible surgical cure. They got a neurosurgeon, who got all OR teams, (anesthetic and nursing) all mobilized to site, no fee demanded yet, to, albeit sadly much belatedly, try salvage a most desperate situation. Surely, these workers should not be the subject of this justifiable outrage, but the health system of the country concerned at that time.

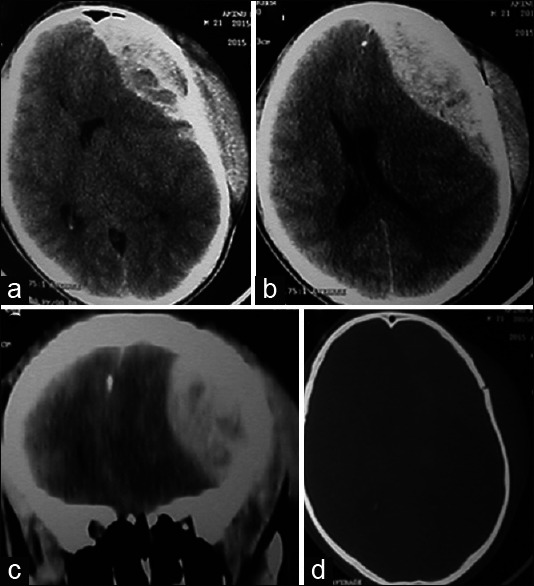

Curiously, and most dramatically, a pretty much identical situation (please take another look at the brain CT images of the two cases) repeated itself in the same health facility in just 24 h later, but this time with a more positive outcome. And the difference? Just one of the points being made: The relations of the second patient were a little more fortunate, somewhat more financially able to pay for the same neuroimaging faster than the first. Even so, the costs of the surgical care, operative/perioperative and administrative, of this salvaged case also had to be waived by this hospital for the life-saving surgery to take place in the middle of the night. These hospital bills were settled by the relations only months later, and that only instalmentally.

One is therefore compelled to assert that the fatal delay in obtaining the life-saving neuroimage for the first case surely has nothing to do, except one be sorely mistaken, with the treating hospital. They did not own this imaging facility. They could not be expected to take their own money to go pay for imaging study in another section of the town for the same patient they already were treating, as-yet for free, in their own facility!

This is indeed the reason we wrote that report. It was our own outrage at an inhuman health system that is modeled after a POS financing, for a population of people majority of which live below the poverty line.[11,12] We were not enthused, a bit, about this case.

It is therefore hoped that cases like the ones in the said tale would compel a global rethink, actually a revolution, in the way the health care needs of the LMICs are addressed. That the OOP payment for health care model is too inhuman a health financing solution to last another decade in any region of the world.[6,12] And our own penny-worth opinion for a start is that an emergency be declared, calling for the World Health Assembly if necessary, to undertake, forthwith, a holistic diagnostic evaluation and treatment of this neglected disease of the health systems of most developing countries.

REFERENCES

-

1.Adeleye AO, Fasunla JA, Young PH. Skull base surgery in a large, resource-poor, developing country with few neurosurgeons: Prospects, challenges, and needs. World Neurosurg. 2012;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

2.Adeleye AO, Okonkwo DO. Inter-hospital transfer for neurosurgical management of mild head injury in a developing country: A needless use of scarce resources? Indian J Neurotrauma. 2011;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

-

3.Adewole DA, Adebayo AM, Udeh EI, Shaahu VN, Dairo MD. Payment for health care and perception of the national health insurance scheme in a rural area in Southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:648–54. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

4.Adewole DA. The impact of political institution and structure on health policy making and implementation: Nigeria as a case study. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2015;44:101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

5.Dienye PO, Brisibe SF, Eke R. Sources of healthcare financing among surgical patients in a rural Niger Delta practice in Nigeria. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

6.Ir P, Bigdeli M. Removal of user fees and universal health-care coverage. Lancet. 2009;374:608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

7.Kim JY, Chan M. Poverty, health, and societies of the future poverty, health, and societies of the future view point. JAMA. 2013;310:901–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

8.Mansouri A, Ibrahim GM. Moving forward together: The lancet commission on global surgery report and its implications for neurosurgical procedures. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:751–2. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1100269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

9.Raykar NP, Bowder AN, Liu C, Vega M, Kim JH, Boye G, et al. Geospatial mapping to estimate timely access to surgical care in nine low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;385(Suppl 2):S16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

10.WHO Global Health Observatory: World Health Statistics. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/en/index.html .

-

11.World Bank, Nigeria: The World Development Indicators. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 28]. Available from: http://www.data.worldbank.org/country/Nigeria .

-

12.Yates R. Universal health care and the removal of user fees. Lancet. 2009;373:2078–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]