Abstract

Objectives:

This study assessed intimate partner violence (IPV) and alcohol use in an urban population in Pune, India. The prevalence of IPV and alcohol use was assessed along with the correlation of IPV with alcohol and other variables.

Materials and Methods:

The study was cross-sectional, questionnaire-based. The materials used were the hurt insult threaten scream (HITS) scale, the alcohol use disorders identification test, and a brief psychosocial questionnaire. Systematic random sampling was done on the target population. Regression analysis of various factors in relation to HITS score was done.

Results:

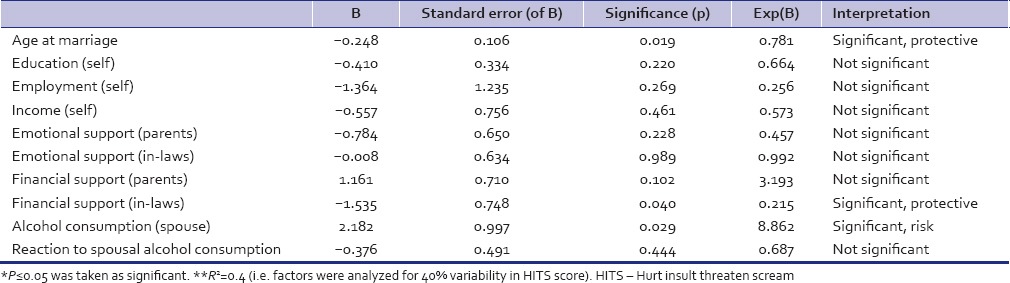

Sample size (n) was 318 individuals. Prevalence of IPV was found to be 16% and the victims were mostly women. Prevalence of alcohol use was 44%, of which 8.9% were harmful users. No female subjects consumed alcohol, but 94% were aware of their husband's alcohol consumption. No significant correlation was found between IPV and education (P = 0.220) or income of women (P = 0.250). Alcohol consumption by males was a significant risk factor for women experiencing IPV (σ = +0.524; P< 0.001). Regression analysis also revealed that increasing marital age (P = 0.019) and financial support from in-laws (P = 0.040) were significantly protective.

Conclusion:

IPV prevalence was less than the national average for India, but the majority of victims was women. The most common type of IPV was verbal. Alcohol use prevalence was higher than the national average, but harmful use was lower. Alcohol use is a significant risk factor for IPV. Education and income of women were not significantly protective against IPV but increased age at marriage and support from in-laws were.

Keywords: Alcohol, HITS, intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to any physically, psychologically, or sexually harmful behavior in an intimate relationship.[1] The three levels of IPV are Level I abuse (pushing, shoving, grabbing, throwing objects to intimidate, or causing damage to property and pets), Level II abuse (kicking, biting, and slapping), and Level III abuse (use of a weapon, choking, or attempt to strangulate). There is substantial evidence that suggests IPV may lead to a wide range of both short-term and long-term physical, mental, and sexual health problems.[2] The incidence of IPV ranges widely between 8 and 50% across South Asia and the United States of America.[3,4,5] About 31% of Indian women have experienced IPV at some point in their marital life as per the available National Family Health Survey (NFHS) III data.[6]

The average alcohol consumption in India is about 4 L/adult/year; about 21% of males consumed alcohol and more than half of those consuming alcohol fulfilled the criteria for hazardous drinking.[1]

The existing literature shows that men who drink at harmful levels and women who drink any alcohol are more likely to be involved in IPV in comparison to light drinkers among men and abstainers among women, respectively.[3,7] Previous studies have shown that when the perpetrator is under the influence of alcohol or is a problem drinker, there is a significantly higher incidence of IPV (up to 2–7 times) than in the general population or in those injured by other means.[8,9]

Several factors are known to predict IPV among women sufferers at the hands of an alcoholic spouse. These are:

Lower educational level of women

Poverty

Higher educational/socioeconomic status of women than their spouses

Women with economic autonomy having a relation with an alcoholic partner irrespective of caste and economic status[3]

Accepting the idea that alcohol leads to aggressive behavior

Such a phenomenon having social approval and more importantly

On the contrary, higher socioeconomic status and good social support, equally high level of education in both husband and wife appear to render some protection against IPV.[7,14]

To understand how alcohol plays a role in IPV, we need to explore various factors that influence each of them. One proposed theory to explain the influence of various factors in the association of alcohol and IPV states that there are many distal influences that may not necessarily cause violence but under influence of a proximal influence can trigger violence.[15,16]

Several factors seem to influence role of alcohol abuse in causing IPV. First, cultural factors such as the strongly prevalent belief in society that alcohol can encourage violent behavior after drinking increase the use of alcohol as an excuse for violent behavior. The attitude of gender discrimination against females in the South Asian population, a discriminatory way of upbringing coupled with poor self-esteem, also condones abuse of females.[4] The association of IPV and alcohol may be more concurrent and also a manifestation of expression of masculinity on the part of men, especially when the concept of shared liability of domestic responsibilities is not accepted. This leads to stress in a marital relationship and consequent IPV. Excessive drinking by any partner can, in addition, lead to problems in child care, infidelity, marital disharmony, and violence.[17] Second, personal factors such as opposition by the spouse toward the partner's excessive drinking, or attempts to put restrictions on his drinking amount and behaviors may lead to IPV. Often IPV is offered as an excuse to be able to exert control and power, and alcohol is just an escape from taking responsibility for such violent behaviors. In some, alcohol per se may increase the distortions of power and control motives. Third, pharmaco-cognitive effects of alcohol are known to increase aggressive responsiveness of people with low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin. Fifth, many neuropsychological impairments noted in alcoholics contribute to violence. These are as follows:

Severe impairment of attention, concentration, cognitive flexibility, and executive cognitive functioning

Intensification of negative emotions such as depression which are associated with increased risk of IPV

Impaired ability to exert self-control, learning, and delay gratification leading to aggression

Impaired capacity to understand, use and process information constructively leading to misinterpretation of their partners’ actions and distorted conclusions which in turn increase the risk of indulging in IPV

Increased irritability, short temperedness, and anger experienced as withdrawal effects of alcohol make a person more sensitive and responsive rendering them prone to IPV.[18,19,20,21,22]

Finally, contextual factors such as when the male partner excessively indulges in alcohol leading to neglect of responsibilities toward the family, further rendering him incapable of providing financial support, assisting in child care, and accusing his spouse of infidelity. The above mentioned situations precipitate or exacerbate marital disharmony thereby increasing the risk of IPV.[23]

Thus, we see that both IPV and alcohol use lead to unsatisfactory intimate/marital relationship. Although there have been studies in the past on both alcohol use and IPV, studies that correlate both are scarce especially in our urban settings. Therefore, it would be interesting to examine how both of these factors influence and interact with each other, what consequences they lead to within such a relationship, and how they are affected by the socioeconomic factors of the victim and intimate partner. Moreover, it has been suggested by the World Health Organization (WHO) that urgent research is required to build the evidence base and address the current lack of such information.[2]

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of IPV and alcohol abuse in the sample urban population and to investigate the possible association between the two and their correlation with socioeconomic and other factors. We hypothesize that increasing alcohol consumption contributes to IPV. In addition, we would like to identify other socioeconomic factors correlation with IPV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and sample population

This project was carried out on participants in the city of Pune in the state of Maharashtra, India. Households were selected by systematic random sampling. Ethical clearance Institutional Ethical board had cleared the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Age of respondent ≥18 years

Respondent who had been married and residing together continuously for at least 1 year

Ability of the respondent to understand and respond to the questions presented

Informed consent of the respondent taken in writing.

Exclusion criteria

Incompletely or improperly answered questionnaires

Refusal of informed consent to participate in the study.

Data collection

The questionnaires were administered in English and a validated local language version. Individuals were interviewed separately from their spouses. Female participants were interviewed in the presence of a female attendant. In addition to information on IPV and alcohol abuse, background data on education, duration of being in relationship, and socioeconomic status of participants were collected.

The urban area selected for the study had a total of 836 families residing. Data available from local council suggested that the monthly household income in each building included would range from Rs. 10,000 to Rs. 40,000 approximately and the education of the residents would vary from Class V to graduates. Based on this and available national prevalence data and statistical considerations, a minimum sample size of approximately 129 couples was found to be suitable by the biostatistician of the Institute. The target population was preliminarily divided into groups based on socioeconomic and educational characteristics assumed from their area of residence (“urban slum,” “residential apartments,” etc.) and suggested systematic random sampling was done by selecting every fourth flat in each residential building or every fourth house in the urban slum. The numbering was done using the layout map provided by the local council. A total of 136 couples (272 individuals, 136 male and 136 female) participated in the study. In addition, 26 individual females and 20 individual males participated. Although these individuals were married and fulfilled other inclusion criteria, their spouses were not available at the time the study was conducted.

Data gathered from such individuals were used during analysis of selected parameters only. The total sample size (N) including couples and individuals was 318.

Measurement instruments

Hurt insult threaten scream questionnaire

In this study, the hurt insult threaten scream (HITS) scale was administered to all participants. It is a four-item scale with well-documented internal reliability and concurrent validity. However, its sensitivity is lower in men than women and varies among different populations.[24,25,26,27] It involves questions about physical, emotional abuse, and threats but not sexual abuse. A score of more than ten for women and eleven for men was taken as the cutoff to indicate the presence of IPV.

Alcohol use disorders identification test

The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) was developed by the WHO as a simple method of screening for excessive drinking and to assist in brief assessment. AUDIT stresses on identification of hazardous drinking.[28] AUDIT differs from other self-report screening tests in that it was based on data collected from a large multinational sample and used an explicit conceptual statistical rationale for item selection. AUDIT has been validated for use in primary health care patients and is the only screening test that identifies hazardous and harmful alcohol use as well as dependence. Other advantages include it being rapid, brief, and flexible with high internal consistency and high test-retest reliability (r = 0.86). These characteristics have been established in several language versions and across several Nations.[29]

Data analysis

IPV was marked as present when HITS scale score was 10 for women and 11 for men; Alcohol abuse was marked as present hwen AUDIT score was ≥ 8. The other factors such as use of alcohol by participants and their socioeconomic factors were also analyzed to see if they have any implication on occurrence of IPV. Chi-square and Pearson's Correlations tests and regression analysis were used in the statistical analysis done using SPSS Inc. Released 2008. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.

RESULTS

Population characteristics

A total of 318 individuals were included in the study, of whom 272 participated with their spouses. Where spouses could not take part, 20 males and 26 females participated singly.

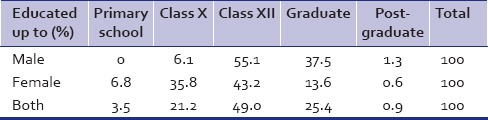

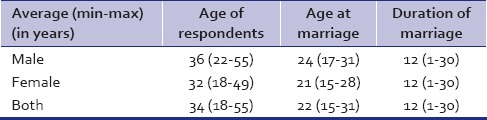

Most males were educated up to Class XII or higher while most women had qualified between Class X and XII [Table 1]. The majority (96.1%) of men was employed whereas the figure for females was only 17.9%. The age at marriage was higher for men (24 years [range: 17–31]) than women (21 years [range: 15–28]) [Table 2]. A very large number of males (96.1%) were employed while only few females (17.9%) were employed. The monthly income of majority of men was in the range of Rs. 10 to forty thousand (93.8%) while majority of women had <Rs. 500 (83.9%).

Table 1.

Educational qualifications of subjects

Table 2.

Age characteristics and duration of marriage of subjects

Alcohol consumption

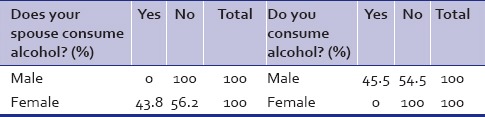

It is very interesting to note that the reporting of alcohol intake by spouse matches with self-reporting of consumption by both genders [Table 3]. Whereas 45.5% of men self-reported to be consuming alcohol, 43.8 of women also mentioned that their spouses consumed alcohol. The average AUDIT (only males) score was 2.26 (range: 0–18) while 8.9% had a score of more than 8.

Table 3.

Acohol consumption

Intimate partner violence prevalence

The overall prevalence of IPV was 8.5%, 26 women (16%) suffered from IPV while only one male (0.6%) reported similar experience. The mean HITS (women) score was 6.09 (range: 5.86–6.32 and SD = 2.089). The most serious type of IPV as detected by HITS was screaming (3.19), followed by threat (2.88), insult (2.73), and hurt (2).

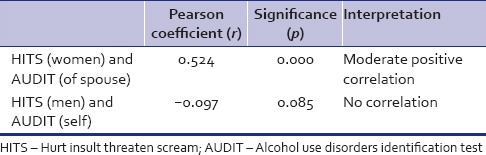

Correlation of hurt insult threaten scream and alcohol use disorders identification test

Table 4 shows moderate positive correlation between the HITS score of the women and the AUDIT score of their spouses. However, there is no correlation of HITS (men) and their AUDIT score.

Table 4.

Correlation of HITS and AUDIT

DISCUSSION

Intimate partner violence

Prevalence

It was found that 16% of women had experienced (IPV) in the past year. The mean HITS score (only female subjects) was 6.09 with a range of 5.86–6.32. Only one male participant had a HITS score of 11. This is very similar to the 19% reported by Ackerson et al.[30] They had covered both rural and urban areas while ours was only an urban population. Thus, it appears that it is mainly the women who are victims of IPV.

The most recent Indian survey (NFHS III, conducted in 2005–2006), a nationally representative survey of women of reproductive age, estimated that 35% of women had experienced physical violence perpetrated by their current or former spouses and 27% had experienced it in the past year.[31] However, our figures are similar to the figure of 15.1% reported in a nationally represented study from Turkey.[32]

Type of intimate partner violence

The most common type of IPV perpetrated among our subjects was screaming while Ahuja et al. had reported physical violence.[33] This is probably due to the absence of illiterate women and a reasonably higher average age of women participating in our study; the opposite of both of these are considered to put women at increased risk of violence.[32] On the contrary, Babu and Kar had found that psychological abuse is more common than physical.[34] Probably education of women may be protective against physical IPV. This would need larger studies to clarify.

Alcohol consumption

The prevalence of alcohol consumption among men was much higher (44%) than the national average of 21% [Table 3] but only 8.9% were harmful users while the national figure for harmful use is 50% of the alcohol consumers.[1] On the contrary, it is surprising that none of our female participants consumed alcohol but were able to tell quite accurately whether their spouses did so or not there was no significant difference between their assessment and acceptance by the men (P = 0.73) [Table 3]. It is possible that most men do not hide their drinking from their spouses. Benegal had reported that 5% of Indian women consume alcohol.[35] Mean AUDIT score (of males only) was 2.26 and maximum score was 18. Thus, it seems that although prevalence of alcohol consumption among our male subjects was relatively higher than NHFS data, the majority of them does not fit the criteria for hazardous drinking as per the AUDIT questionnaire, implying that their drinking patterns are much safer.

Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence

Education

The majority of our participants was educated up to higher secondary, i.e., class 12th (49%) [Table 1]. None of the subjects were illiterate and very few had completed higher studies (postgraduation) (1.9%). Although women lagged in education, it did not influence occurrence of IPV [Table 5] (P = 0.220). Although, in two other studies, similar findings were noted, they had a larger proportion of illiterate population (28–30%). This is surprising as Krishnan and Ackerson et al. had reported that women with lower educational level likely to suffer more and when educated higher than spouse are more likely to report more. In our study, we did not find any such correlation probably because number of those women with education higher than spouses was minimal and difference between education status of both wife and husband was not much.[30,36,37]

Table 5.

Regression analysis of factors in relation to HITS score

Employment and income

Our study investigated the impact of employment status of women on prevalence of IPV but did not find any significant association (P = 0.25). A majority of the men were employed (96.1%) while only 17.9% of women were so. Further, level of income contributed by either to the family also did not have much effect. Krishnan had reported that higher socioeconomic status of women put them at risk of IPV.[38] Since the number of women employed in our sample was less and very few earned more than their spouses no such relationship could be established.

Age at marriage and social support systems

An interesting finding of this study has been that 22.8% of the women received emotional support while 31.6% received financial support from their own parents.

Of the women, 42.6% received emotional support while 31.6% received financial support from their in-laws. Financial support to the wife by her in-laws has been significantly (P = 0.04) protective against IPV [Table 5].

However, our study shows that both financial and emotional supports from own parents were not very protective. This is a very encouraging sign which probably reflects the high level of maturity of the community and shows a positive attitude toward daughters-in-law; therefore, this finding needs to be highlighted as a positive preventive measure in a community for IPV against women. Ahuja et al. in a study found that women with higher levels of social support were significantly less likely to report physical and psychological violence, the latter being much lesser than the former though they did not specify the type of support.[33]

Studies from Turkey and India (NFHS III) have shown that when the age at which women marry is delayed and if accompanied by higher education it resulted in lower risk of IPV, especially physical and sexual.[6,32] Although some of our subjects had married quite early (15 years of age for women and 17 for men), the average age at marriage was 21 for women and 24 for men [Table 2]. This probably explains why our subjects had experienced less physical type of IPV. Regression analysis, however, did not reveal any significant correlation of age at marriage with IPV (P = 0.78) [Table 5].

Further evaluation of data revealed that the incidence of IPV was highest when the age difference between the spouses was just 2–4 years (58% of such subjects experienced IPV). While in those who have no age difference, IPV was not reported and among those having an age difference of more than seven years, only 8% reported IPV in the past 1 year. However, these figures failed to achieve any statistical significance (P = 0.16).

Probably, when ages are similar, there is a tacit agreement on issues while when age difference is large, there is more maturity in the relationship dynamics. However, when the difference is not much, probably, there is a tussle to establish authority over the other that leads to IPV. Since these factors were not evaluated, in this study, it would be prudent to explore the validity of this finding and search for reasons for it.

Association of alcohol consumption with intimate partner violence

One of the most important findings of our study has been the unequivocal relationship established between use of alcohol by the husband and the infliction of IPV on the wife. The increasing severity of alcohol abuse significantly contributes to occurrence of IPV (P = 0.00) [Table 4].

It was noted that alcohol consumption by men puts the spouse at a significant risk of incurring IPV from him (P = 0.02). These findings have been arrived at after controlling for other variables such as employment, emotional and financial support, education, and age at marriage. These findings are in consonance with findings from several other studies.[2,3,7,39] Ahuja et al. found that more than half of the women who reported that their husbands got drunk once a week also reported having suffered both physical and psychological violence from their husbands, but they did not find any statistical correlation which they concluded was because of poor reporting of alcohol use by the men.[33]

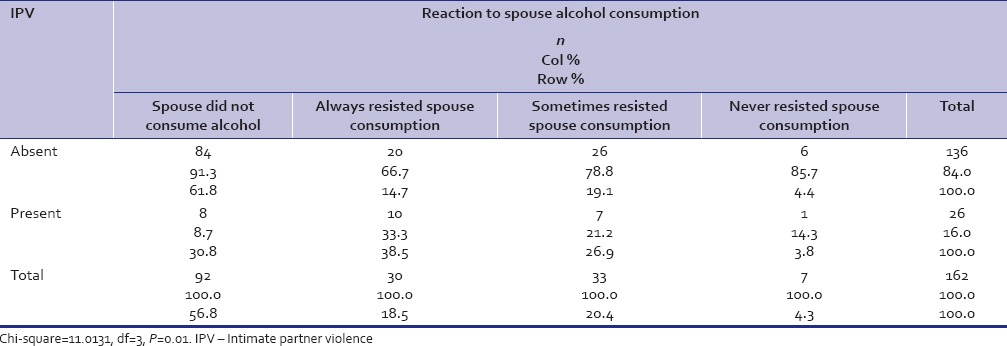

Our study finding is more robust as a standard screening instrument was used and most of the women were aware of their spouse's drinking habits. However, their reaction toward it varied. The majority of the women (18.5%) always opposed it, 20.4% sometimes opposed it, and 4.3% did not oppose it. Interestingly IPV was significantly higher when women opposed their spouse's drinking (P = 0.01) [Table 6].

Table 6.

Relation of wife's reaction to spouse alcohol consumption and IPV

Probably, IPV is triggered by the constant opposition by women to their husband's drinking, especially when she tries to argue against his drinking or tries to restrict the amount of alcohol consumption.[40] Although in our study, we had not ascertained when the arguments occurred, future studies should consider evaluating the factors immediate to onset of IPV when one of the partners in consuming alcohol and other is resisting it.

CONCLUSION

IPV prevalence was less than the national average for India, but the majority of victims was women. The most common type of IPV was verbal. Alcohol use prevalence was higher than the national average, but harmful use was lower. Alcohol use is a significant risk factor for IPV. Education and income of women were not significantly protective against IPV but increased age at marriage and support from in laws were. IPV is more likely when women oppose their spouse's drinking of alcohol.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: Taking action and generating evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Costa G, Nazareth I, Naik D, Vaidya R, Levy G, Patel V, et al. Harmful alcohol use in Goa, India, and its associations with violence: A study in primary care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:131–7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Suresh S, Ahuja RC. Domestic violence and its mental health correlates in Indian women. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:62–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinsheimer RL, Schermer CR, Malcoe LH, Balduf LM, Bloomfield LA. Severe intimate partner violence and alcohol use among female trauma patients. J Trauma. 2005;58:22–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000151180.77168.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S. Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005-2006 national family health survey. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28:773–807. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banks HD, Randolph SM. Substance abuse and family violence. In: Hamptom RL, editor. Family Violence: Prevention and Treatment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 288–308. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan TK, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Rural, urban influenced and urban differences among domestic violence arrestees. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16:266–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyriacou DN, Anglin D, Taliaferro E, Stone S, Tubb T, Linden JA, et al. Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence against women. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1892–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahams N, Jewkes RK. ‘I do not believe in democracy in the home’: Men's relationships with and abuse of women. Tygerberg, South Africa: Women's Health, Centre for Epidemiological Research in Southern Africa (CERSA) 1999:27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field CA, Caetano R, Scott N. Alcohol and violence related cognitive risk factors associated with the perpetration of intimate partner violence. J Fam Violence. 2004;19:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton-Moss BJ, Manganello J, Frye V, Campbell JC. Risk factors for intimate partner violence and associated injury among urban women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:239–48. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-5518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riger S, Raja S, Camacho J. The radiating impact of intimate partner violence. Journal Interpers Violence. 2003;17:184–204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stappenbeck CA, Fromme K. Alcohol use and perceived social and emotional consequences among perpetrators of general and sexual aggression. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:699–715. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonard KE. Rockville, MD: NIH publication no. 93-3496; 1993. Research monograph 24: Alcohol and interpersonal violence – Fostering multidisciplinary perspectives. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Drinking patterns and intoxication in marital violence: Review, critique and future directions for research; pp. 253–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:369–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. World Health Organization Intimate Partner Violence and Alcohol Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith CA, Elwyn LJ, Ireland TO, Thornberry TP. Impact of adolescent exposure to intimate partner violence on substance use in early adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:219–30. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giancola PR. Executive functioning and alcohol-related aggression. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:541–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafson R. Alcohol and aggression. J Offender Rehabil. 1994;21:413. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubio G, Jiménez M, Rodríguez-Jiménez R, Martínez I, Iribarren MM, Jiménez-Arriero MA, et al. Varieties of impulsivity in males with alcohol dependence: The role of cluster-B personality disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1826–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders DG, Kindy P., Jr Predictors of physicians’ responses to woman abuse: The role of gender, background, and brief training. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:606–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02599714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shillington AM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL. Is there a relationship between heavy alcohol use and HIV high risk sexual behaviors among general population subjects? International Journal of the Addictions. 1995;30:1453–78. doi: 10.3109/10826089509055842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen PH, Rovi S, Vega M, Jacobs A, Johnson MS. Screening for domestic violence in a predominantly Hispanic clinical setting. Fam Pract. 2005;22:617–23. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: A short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen PH, Rovi S, Washington J, Jacobs A, Vega M, Pan KY, et al. Randomized comparison of 3 methods to screen for domestic violence in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:430–5. doi: 10.1370/afm.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills TJ, Avegno JL, Haydel MJ. Male victims of partner violence: Prevalence and accuracy of screening tools. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT. AUDIT JC, Saunders JB, ools. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:447–52. for Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6a; 2001. [Original English]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:272–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV. Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: A population-based study of women in India. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:507–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.I. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007. International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India; p. 540. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ynternational Ins I, TI, Tnatio AS, Heise L. What puts women at risk of violence from their husbands?. Findings from a large, nationally representative survey in Turkey. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27:2743–69. doi: 10.1177/0886260512438283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahuja RC, Bangdiwala S, Bhambal SS, Dipty J, Jeyaseelan L, Shuba K, et al. Washington, DC: USAID/India; 2000. May, Domestic Violence in India a Summary Report of a Multi-site Household Survey. International Clinical Epidemiologists Network (INCLEN) International Center for Research on Women. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babu BV, Kar SK. Domestic violence against women in Eastern India: A population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benegal V. India: Alcohol and public health. Addiction. 2005;100:1051–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha A, Mallik S, Sanyal D, Dasgupta S, Pal D, Mukherjee A. Domestic violence among ever married women of reproductive age group in a slum area of Kolkata. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:31–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puri M, Frost M, Tamang J, Lamichhane P, Shah I. The prevalence and determinants of sexual violence against young married women by husbands in rural Nepal. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:291. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krishnan S. Gender, caste, and economic inequalities and marital violence in rural South India. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26:87–99. doi: 10.1080/07399330490493368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeyaseelan L, Sadowski LS, Kumar S, Hassan F, Romino L, Vizcana B. World studies of abuse in the family environment – Risk Factors For Physical IPV. Inj. Control Safe Promot. 2004;2:117–24. doi: 10.1080/15660970412331292342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ptacek J. The tactics and strategies of men who batter: Testimony from women seeking restraining orders. In: Cardarelli AP, editor. Violence between Intimate Partners: Patterns, Causes, and Effects. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1997. pp. 104–23. [Google Scholar]