Abstract

Background:

Substance misuse is an increasing problem in urban and rural India. The utility of community-based interventions and preventive strategies are increasingly emphasized in this context. The drug de-addiction and treatment center, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, has been running a drug de-addiction and treatment clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital, Kharar, District Mohali, Punjab, since 1998. As part of an effort to enhance this community outreach program, community-based drug awareness and treatment camps have been organized since March 2004 in villages in and around Tehsil Kharar of Mohali.

Aim:

To study the impact of the drug awareness and treatment camps on the attendance of patients at the community outreach drug de-addiction and treatment clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital.

Methods:

Sociodemographic and clinical variables, including treatment outcome-related variables, of patients attending the clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital, before and after the camps were compared.

Discussion and Conclusion:

The study showed a positive impact on drug awareness and treatment camps held in the community on outpatient attendance at a community outreach clinic, with attendance increasing more than 1.8 times.

Keywords: Camps, community services, de-addiction, rural practice, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Settings

Substance misuse is an increasing problem in urban and rural India. The utility of community-based interventions and preventive strategies are increasingly emphasized in this context. Community-based programs create awareness in the community of the existence of alcohol and other drug-related problems, bring services closer to substance misusing individuals and their families, and help foster community responses against substance misuse.[1,2,3]

Community outreach clinics

Outreach services have several broad objectives

To identify substance misusing individuals in main catchment areas and adjoining localities and to initiate the process of pretreatment counseling (clarify myths and misconceptions associated with drug misuse)

To focus on health and social consequences of socially sanctioned drugs such as alcohol and tobacco as well as illicit drugs such as heroin and suggest possible remedial steps

To provide low-cost treatment services within the community

To facilitate formation of local support groups as well as self-help groups.

The physical infrastructure is provided by the community or organized by the community, and the service delivery team of a tertiary care de-addiction center provides the core team for treatment.

The department and team

The drug de-addiction and treatment center (DDTC) of the Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, has been running a community outreach drug de-addiction and treatment clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital, Kharar, District Mohali, Punjab, since 1998. The Civil Hospital at Kharar is an important hospital in the area and provides services to Kharar Town and about 120 surrounding villages, catering to the needs of about 1.5 lac people.

The team from DDTC, PGIMER, runs the outreach clinic every Saturday from 10 am to 1 pm. The team consists of a psychiatrist and a psychiatric social worker (PSW). The psychiatrist carries out the clinical assessment, formulates the diagnosis and management plan, and recommends pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments. The PSW carries out a psychosocial assessment and intervention including educates the family about the illness and facilitates the implementation of treatment and the rehabilitation of the patient.

The intervention

As part of an effort to create awareness about treatment services, clarifying myths and misconceptions about substance abuse, community-based drug awareness, and treatment camps have been organized since March 2004 in villages in and around Kharar Tehsil in Mohali, Punjab. The camps were organized once every month, usually on a Sunday in the morning hours. About 2–3 weeks prior to the camp, the PSW would visit the chosen village, meet local leaders, and communicate with them the interest of the team from DDTC in conducting a camp in that village. In the large majority of cases, the response was positive and enthusiastic. On the day of the camp, a team from DDTC, consisting of two doctors (usually, one senior and one junior resident), a PSW, a consultant PSW, a nurse, and support staff would visit the village. Stationery in the form of outpatient cards, clinical record sheets, educational posters, and charts; instruments in the form of blood pressure apparatus, weighing scale, and stethoscopes; and medication for detoxification of patients for 1 week would be taken along. In the camp, patients would be registered, intake and pretreatment counseling by the PSW, seen by doctors, prescribed a detoxification regimen for 1 week, if required and be asked to follow-up at the DDTC, PGIMER, or at the community clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital. At the camp, the PSW and the consultant PSW would interact with patients and community leaders educated them about substance abuse and available treatments for the same. Each such camp saw an attendance of about 40 patients, on average and would last for about 5–6 h.

Aim

The aim of the present research was to study the impact of the drug awareness and treatment camps on the attendance of patients at the community outreach drug de-addiction and treatment clinic at Kharar Civil Hospital.

METHODS

Camps began in March 2004. Patient records from April 1998 to March 2010 were retrieved. Relevant data were extracted from the patients seen in the precamp period of April 1998 to March 2004 (72 months) and the postcamp period of April 2004–March 2010 (72 months).

Statistical analysis

An independent samples t-test was used to compare the number of follow-up visits to the community outreach clinic before and after the camps began.

RESULTS

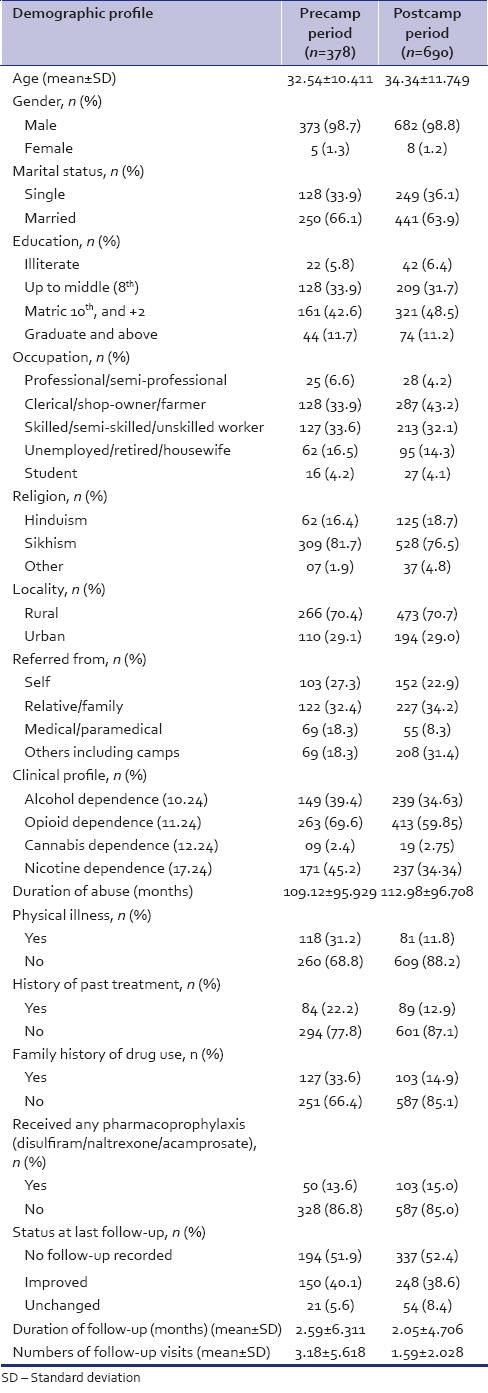

The sociodemographic and clinical profiles of the patients seen in pre- and post-camp periods are compared in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical profile of the patients seen in pre- and post-camp

Precamp period (April 1998–March 2004)

Sociodemographic profile

A total of 378 new patients attended the Kharar Clinic in the period of April 1998–March 2004 (72 months). The majority were male (N = 373, 98.7%), married (N = 250, 66.1%), employed (N = 280, 74.1%), educated (N = 333, 88.4%), Sikhs (N = 309, 81.7%), and from a rural background (N = 266, 70.4%). Most patients sought treatment on their own (N = 103, 27.2%) or were brought to the clinic by their relatives (N = 122, 32.3%).

Clinical profile

A total of 149 (39.4%) patients had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F10.24 as per International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10) and 263 (69.6%) patients had a diagnosis of opioid dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F11.24 as per ICD-10). Most patients (N = 101, 38.4%) were using natural opioids (opium, bhukki, and doda). Nine (2.4%) patients had a diagnosis of cannabis dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F12.24 as per ICD-10) and 171 (45.2%) had a diagnosis of tobacco dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F17.24 as per ICD-10). The majority of patients did not have a physical illness (N = 260, 68.8%) and were treatment naive (N = 294, 77.8%). One hundred and twenty-seven patients (33.6%) had a family history of a substance use disorder. The majority of patients did not receive any pharmacoprophylaxis (disulfiram, naltrexone, or acamprosate) (N = 328, 86.8%) and did not follow-up after first contact (N = 206, 54.5%). The mean number of follow-up visits was 3.18 (standard deviation [SD] =5.618) with a mean follow-up period of 2.59 months (SD = 6.311).

Postcamp (April 2004–March 2010)

Sociodemographic profile

A total of 690 new patients attended the Kharar Clinic in the period of April 2004–March 2010 (72 months), an increase of 1.8 times as compared to the number of new patients who attended the clinic in the 72-month period before the camps began. In this period, outpatient attendance at Kharar Civil Hospital increased only marginally (104,701–108,733 patients; an increase by a factor of 1.04). The majority were male (N = 674, 97.7%), married (N = 441, 63.9%), employed (N = 528, 79.5%), educated (N = 604, 87.53%), Sikhs (N = 528, 76.5%), and from a rural background (N = 473, 68.6%). Patients sought treatment on their own (N = 152, 22.0%) or were brought to the clinic by their relatives (N = 227, 32.9%). Importantly, 302 patients (43.7%) sought treatment at the clinic after attending one of the camps.

Clinical profile

A total of 239 (34.63%) patients had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F10.24 as per ICD-10) and 413 (59.85%) patients had a diagnosis of opioid dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F11.24 as per ICD-10). Nineteen (2.75%) patients had a diagnosis of cannabis dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F12.24 as per ICD-10) and 237 (34.34%) had a diagnosis of tobacco dependence syndrome currently using the substance (F17.24 as per ICD-10). The majority of patients did not have a physical illness (N = 609, 88.2%) and were treatment naive (N = 601, 87.1%). One hundred and three patients (14.9%) had a family history of substance use disorder. The majority of patients did not receive any pharmacoprophylaxis (disulfiram, naltrexone, or acamprosate) (N = 587, 85.0%). Three hundred and forty-nine patients (50.5%) did not follow-up after the first contact. The mean number of follow-up visits was 1.59 (SD = 2.028) with a mean follow-up period of 2.05 months (SD = 4.706). An independent samples t-test showed that the number of follow-up visits for the postcamp patient group was less than those for the precamp patient group (3.18 ± 5.618 vs. 1.59 ± 2.028) and that this difference was statistically significant at P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The pre- and post-camp patient groups were nearly identical in their sociodemographic and clinical profiles. The majority of patients in both groups were married, Sikh, men from a rural background with opioid dependence syndrome being the most common diagnosis. This is consistent with the fact that the catchment area for both groups was the same and was consistent with the sociodemographic and clinical profile reported in other studies in this geographical area.[4,5]

The study found that here was a substantial increase in clinic attendance in the postcamp group and although the duration of follow-ups (in months) in the two groups was similar, the number of follow-up visits in the postcamp group was significantly lesser. It is not immediately clear why this is the case, and the present study did not explore reasons for this.

Studies from India and abroad[6,7,8] have highlighted the utility of the “de-addiction camp” approach as a cheap and effective treatment alternative for patients with alcohol and drug dependence in the community.[9,10] The referenced camps[11] were however different from our camps in being (usually) 10-day inpatient camps.

The salient features of our camps included community participation in the planning and organization of the camps; 1-day outpatient camp, emphasis on dissemination of information about drug de-addiction and the availability of services, and free of cost treatment and dispensing of medications for 7 days.

Our study shows a positive impact of drug awareness and treatment camps held in the community on outpatient attendance at a community outreach clinic. The clinic attendance increased nearly 1½ times. It may be inferred that the increase in the utilization of services was due to the increased awareness of the availability of services for the treatment of drug dependence.

If further research reconfirms these findings, it would be recommendable that camps are used to increase the utilization of community clinics and services.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chavan BS, Gupta N. Camp Approach: A community-based treatment for substance dependence. Am J Addict. 2004;13:324–5. doi: 10.1080/10550490490460337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj L, Chavan BS, Bala C. Community ‘de-addiction’ camps: A follow-up study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta S, Prasantham BJ, Kuruvilla K. Community treatment of alcoholism. Indian J Psychiatry. 1991;33:306–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SM, Giri OP, Misra A, Kulhara P. De-addiction services in the community by a team from a tertiary hospital: Profiles of patients in different settings. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2012;43:288–94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattoo SK, Singh GD, Gupta N, Basu D, Kaur M. Community de-addiction clinic by a tertiary care team: First 100 cases. J Ment Health Hum Behav. 2002;7:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj H, Ray R, Prakash B. Relapse precipitants in opiate addiction: Assessment in community treatment setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:253–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W. Illegal drug abuse and the community camp strategy in China. J Drug Educ. 1999;29:97–114. doi: 10.2190/J28R-FH8R-68A9-L288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranganathan S. The Manjakkudi experience: A camp approach towards treating alcoholics. Addiction. 1994;89:1071–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb02783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purohit DR, Razdan VK. Evaluation and appraisal of community camp approach to opium detoxification in North India. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;4:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nigam AK, Ray R, Tripathi BM. Non completers of opiate detoxification program. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:376–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chavan BS, Priti A. Treatment of alcohol and drug abuse in cAMP setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999;41:140–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]